Abstract

A young male patient presented to our ocular emergency department with chief complaints of progressive pain, redness, diplopia and a right-sided face turn. Ocular examination revealed severely restricted extraocular movements along with retinal folds in the left eye. Initial orbital ultrasound and CT findings were equivocal; however, serology favoured an infective cause. Considering the endemicity of the disease and equivocal investigation findings, a diagnosis of orbital cysticercosis with an atypical presentation was made. The patient was managed medically with a combination of oral albendazole and steroids over a period of 6 weeks to achieve optimal results.

Keywords: ophthalmology, medical management, medical education

Background

In developing nations where human cysticercosis is an endemic disease, orbital involvement is not uncommon. The usual presentation includes recurrent painless redness, ptosis and a moderate amount of extraocular muscle restriction; however, this can vary. The key factors required for appropriate diagnosis and successful management include a specific history of exposure, careful clinical examination, a skilful ultrasonographic evaluation of the orbit followed by a non-contrast CT (NCCT) of the orbit and brain.1–4 Here, we discuss the clinical features, systematic evaluation and management of a case with extraocular cysticercosis with an extensive orbital disease.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old male patient presented to the ocular emergency department with complaints of painful (minimal) restriction of extraocular movements in the left eye for the past 1 month, with recent aggravation (figure 1). Visual acuity was 6/6 and 6/60 in the right and left eye, respectively. Examination revealed diplopia in the primary gaze, which was offset by a right-sided face turn of 25°. Slit lamp examination revealed a diffuse conjunctival congestion in the left eye; however, the anterior chamber and vitreous were free from any inflammatory reaction. Retinal examination revealed chorioretinal folds along the left temporal retina. Examination of the right eye was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

Nine gaze clinical pictures revealing an exodeviation in the primary gaze with restriction of adduction, elevation and depression in the presence of moderate ptosis.

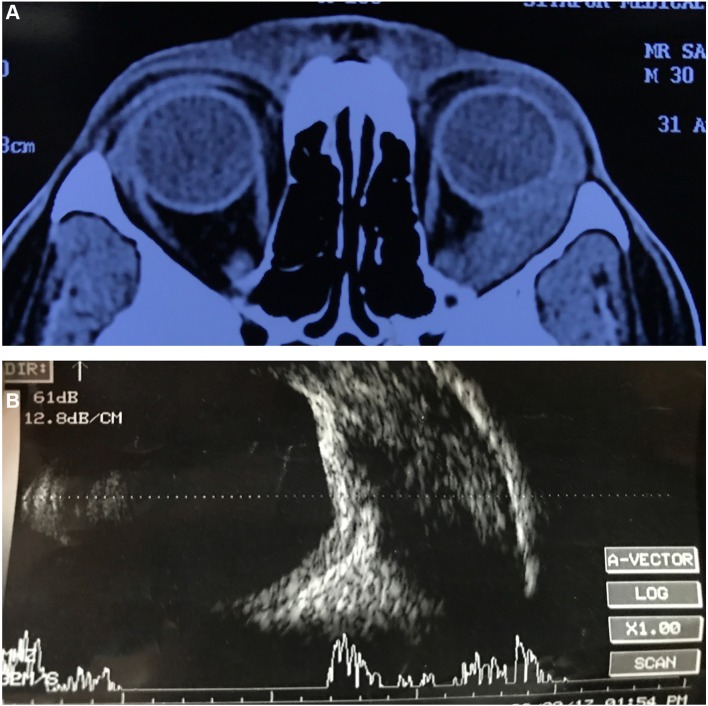

Previously performed NCCT of the orbit and brain showed an extensive homogeneous mass along the left lateral orbit, which was fairly well defined and extending from the orbital apex to just anterior to the lateral orbital rim. The optic nerve was displaced medially, with indentation of the temporal aspect of the globe (figure 2A); however, there was no evidence of bony changes such as remodelling or destruction. Based on the clinical and imaging findings, a probable pathology involving the lacrimal gland, lateral rectus muscle or the orbit was suspected. B-scan ultrasonography of the orbit revealed an extensively thickened lateral rectus with a hypoechoic area but a definite scolex (larval form of Taenia solium) was not appreciated (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Axial sections of CT showing extensive fairly well-defined mass lesion extending from the orbital apex to just anterior to the orbital rim. Lateral rectus muscle could not be made out. (B) Scan ultrasound showing extensively thickened lateral rectus muscle with a large hypoechoic area within.

Haematological investigations for complete haemogram, peripheral blood smear and liver and kidney function tests were essentially within normal limits. Serum ACE levels and antinuclear antibodies were also within normal limits. ELISA for antibodies against cysticercal antigen tested positive (EITB is gold standard and should be used if available). Based on the clinical features, equivocal imaging findings, serology and the endemicity of the disease, a diagnosis of primary lateral rectus muscle cysticercosis was made with atypical presentation.

Investigations

Differential diagnosis

Idiopathic inflammatory orbital disease.

Lacrimal gland tumour.

Secondary orbital disease due to an underlying systemic cause.

Treatment

The patient was initiated on oral prednisolone acetate 1 mg/kg body weight per day from day 1 followed by oral albendazole 15 mg/kg per day from day 3 in two divided doses. The medication was tapered over a period of 6 weeks.

Outcome and follow-up

At the end of 3 weeks, the patient was free from diplopia in the primary gaze along with further restoration of the normal head posture. The extraocular motility took longer to improve, with slight residual restriction in adduction in the left eye even after 2 months (figure 3). Ultrasound revealed significantly reduced lateral rectus muscle thickness (figure 4). At the end of 6 months, the extraocular motilities improved in the absence of any additional ocular or systemic comorbidities.

Figure 3.

At the end of 8 weeks, there was an improvement in ptosis along with significant improvement in extraocular motility.

Figure 4.

B-scan ultrasound at the end of 8 weeks showed significantly reduced lateral rectus muscle thickness.

Discussion

Cysticercosis can involve any part of the ocular as well as periocular tissues. In cases of anterior and posterior segment involvement, a definite diagnosis is possible by direct observation of the cyst and its characteristics.2 5 6 In cases of extraocular muscle involvement, the presentation may typically be one of painless moderate restriction of movement, proptosis and isolated cystic enlargement of the rectus muscle belly with a scolex. Uncommon presentations such as live intraocular mobile scolex and spontaneous extrusion of the scolex have also been reported.7 8 This case presented extensive involvement of the lateral rectus muscle from its insertion to the orbital apex in the absence of a cystic cavity or scolex. In such circumstances, a diagnosis may be made based on strong clinical suspicion, serological evaluation and initial response to empiric treatment.

Primary imaging modality for orbital cysticercosis is B-scan ultrasonography.7 9 It provides real-time information regarding the location, size and number of the cysts, which is vital for the confirmation of diagnosis. It is also necessary for the assessment of treatment response during follow-up; however, the evidence of scolex as a hyperechoic dot or curvilinear structure may not be appreciable in all the cases. Under such circumstances, additional serological tests (ELISA, EITB) are quite useful.1 In this case, it was a minimally painful inflammatory enlargement of the lateral rectus muscle with severely restricted extraocular motility in the absence of any proptosis. Importantly, orbital imaging results did not favour a diagnosis of cysticercosis. Based on the available clinical and imaging findings and our clinical experience, a few important differential diagnoses were considered. First was idiopathic inflammatory orbital disease, despite being a diagnosis of exclusion; however, subsequent investigations and treatment proved it to be an infective cause.

Second, a primary orbital tumour of the lacrimal gland was considered as a close differential diagnosis, but the clinical and radiological findings were not typical for malignancy. Lastly, a diagnosis of a primary orbital involvement due to an underlying systemic disease like lymphoma or other granulomatous disease was considered; however, following preliminary investigations and based on our clinical suspicion and prevalence of the disease in this patient population or similar, a probable diagnosis of an atypical presentation of the extraocular muscle cysticercosis was made and it was treated accordingly.

This case highlights the cysticercosis of extraocular muscle in an atypical manner in an ocular emergency setup of a developing nation, which may otherwise pose a diagnostic challenge due to lack of awareness and the clinical experience. Thus, strong clinical suspicion, in addition to a detailed clinical evaluation and skilful usage of imaging modalities is helpful in achieving a correct diagnosis and thereby optimal anatomical and visual results.

Learning points.

As orbit is popularly known as Pandora’s box, patients presenting with orbital diseases may have varied underlying aetiology ranging from infective pathology to life-threatening malignant conditions.

Orbital cysticercosis is one of the great masquerades of orbital diseases in developing nations.

When presented with such an atypical case, due consideration of age, sex, disease prevalence and the clinical expertise of the treating ophthalmologist is of paramount importance.

Footnotes

Contributors: RM, DA, AP and MSB have evaluated the case in detail followed by optimal intervention to achieve cosmetically and anatomically acceptable results. RM, AD, AP and MSB after critically analysing the educational value of the case wrote the report together.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Rath S, Honavar SG, Naik M, et al. Orbital cysticercosis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, management, and outcome. Ophthalmology 2010;117:600–5. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pushker N, Bajaj MS, Betharia SM. Orbital and adnexal cysticercosis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2002;30:322–33. 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2002.00550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sekhar GC, Lemke BN. Orbital cysticercosis. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1599–604. 10.1016/S0161-6420(97)30090-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Damani M, Mehta VC, Baile RB, et al. Orbital cysticercosis: A case report. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2012;26:457–8. 10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dhiman R, Devi S, Duraipandi K, et al. Cysticercosis of the eye. Int J Ophthalmol 2017;10:1319–24. 10.18240/ijo.2017.08.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murthy R, Samant M. Extraocular muscle cysticercosis: clinical features and management outcome. Strabismus 2008;16:97–106. 10.1080/09273970802262506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swamy DR, Markan A, Behera S, et al. Subretinal cysticercosis with a mobile scolex. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr-2017-223832 10.1136/bcr-2017-223832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Obedulla H, Pujari A, Gupta Y, et al. Spontaneous extrusion of subconjunctival cysticercosis cyst. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:bcr-2017-221470 10.1136/bcr-2017-221470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pujari A, Chawla R, Singh R, et al. Ultrasound-B scan: an indispensable tool for diagnosing ocular cysticercosis. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:bcr-2017-219346 10.1136/bcr-2017-219346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]