Abstract

Bile reflux into the gastric stump and then into the oesophagus is a common event after distal gastrectomy and Billroth II reconstruction. In addition to typical symptoms of nausea, epigastric pain and bile vomiting, acid reflux can also occur in patients with concomitant hiatus hernia and lower oesophageal sphincter incompetency. Diverting the bile away from the oesophagus by conversion into a Roux-en-Y anastomosis or by completion gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy have so far represented the mainstay of treatment. We report the first case of magnetic sphincter augmentation to relieve refractory reflux symptoms after Billroth II gastrectomy. The procedure was performed through a laparoscopic approach and proved very effective at 1-year follow-up.

Keywords: gastro-oesophageal reflux, gastrointestinal surgery

Background

Bile reflux into the gastric stump and then into the oesophagus is a common event after distal gastrectomy and Billroth II reconstruction. Diversion of the bile route away from the stomach by a Roux-en-Y anastomosis has so far represented the mainstay of treatment.1 However, regurgitation and acid reflux may persist in about one-third of these patients due to a concomitant hiatus hernia and an incompetent lower oesophageal sphincter.2 More recently, the magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) procedure has been developed as a less disruptive and more standardised antireflux surgical option for patients with primary gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.3 We hypothesised that MSA, by decreasing both acid and biliary gastro-oesophageal reflux, could effectively relieve symptoms and control oesophagitis even in patients with previous partial gastrectomy.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old white man with a body mass index of 32 presented with intractable reflux symptoms and grade B oesophagitis 44 years after partial gastrectomy and Billroth II reconstruction for perforated peptic ulcer. He had a 5-year history of severe heartburn and regurgitation, especially overnight and after meals, epigastric pain and bile vomiting. The patient was on therapy with proton-pump inhibitors (lansoprazole 30 mg two times per day) with only partial relief of heartburn, and failed to respond to sucralfate and prokinetics (domperidone and metoclopramide). There were no significant comorbidities except for a well-controlled mild hypertension.

Investigations

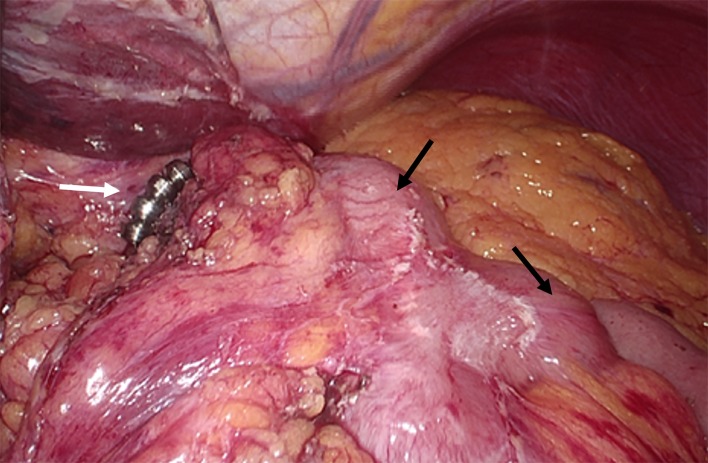

A barium swallow study showed no evidence of hiatus hernia or gastro-oesophageal reflux. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a 2 cm hiatal hernia, grade B oesophagitis and an erythematous gastrojejunal anastomosis with bile pooling in the gastric remnant (figure 1). Biopsies were negative for malignancy and Helicobacter pylori infection. Impedance–pH testing showed combined acid and non-acid reflux; on high-resolution manometry, oesophageal peristalsis was normal and resting lower oesophageal sphincter pressure was 11 mm Hg.

Figure 1.

Preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: bile staining the distal oesophagus (A); grade B oesophagitis (B); hyperaemia of the gastrojejunal anastomosis (C).

Differential diagnosis

Adenocarcinoma of the gastric stump, a typical late complication of Billroth II operation (fourfold increased risk >10 years after surgery), was excluded based on the endoscopic biopsy findings. Therefore, either an open Roux-en-Y conversion or a MSA implant possibly via a laparoscopic approach was offered to the patient as remedial surgical options. The patient expressed his preference for the laparoscopic procedure and signed the informed consent.

Treatment

Pneumoperitoneum was established with the Hasson technique. Using a 5-port laparoscopic approach, upper abdominal adhesiolysis was performed. The gastrojejunal anastomosis appeared regular; the afferent jejunal loop was about 20 cm in length and there was no Braun anastomosis. A small hiatus hernia was identified and the gastro-oesophageal junction was completely reduced in the abdominal cavity. After encircling the distal oesophagus with a Penrose drain, a standard posterior crural repair with three non-absorbable stitches was performed. A tunnel was made between the oesophageal wall and the posterior vagus nerve, and a 16-bead MSA was inserted and locked (figure 2). Total operative time was 80 min and there were no intraoperative complications.

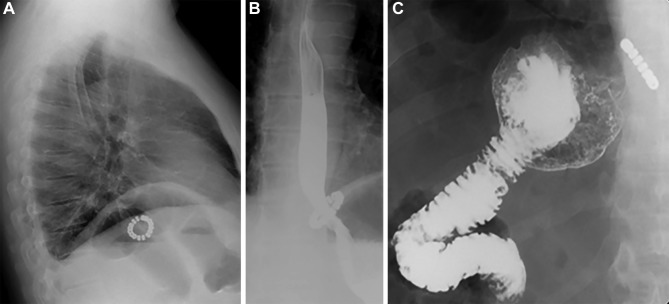

Figure 2.

Laparoscopic view: MSA device (white arrow); gastric remnant (black upper arrow); afferent jejunal limb (black lower arrow). MSA, magnetic sphincter augmentation.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperative course was uneventful. A chest X-ray performed on postoperative day 1 showed the correct position of the device. The patient started to eat a semisolid diet and was discharged home the same day. At 1, 6, and 12 months’ follow-up visits, the patient was off medication, was eating liberally and did not complain of any heartburn, regurgitation or bile vomiting. The Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease-Health Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) score decreased from 26 to 2. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy confirmed healing of oesophagitis, and a barium swallow study was regular (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Postoperative lateral chest film showing the MSA device below the diaphragm (A); barium swallow study showing regular passage of the contrast medium through the gastro-oesophageal junction (B) and emptying of the gastric remnant (C). MSA, magnetic sphincter augmentation.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the use of MSA in a patient suffering from postgastrectomy duodeno-gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Distal gastrectomy with Billroth II reconstruction can lead to de novo reflux or worsening of pre-existing reflux symptoms in about one-third of patients.2 First-line therapeutic approach should consist of proton-pump inhibitors, mucosal protecting or bile-binding agents, and/or prokinetics. However, in patients with severe/refractory symptoms, conversion of the Billroth reconstruction into a 60–80 cm Roux-en-Y jejunal loop anastomosis or even a completion gastrectomy with oesophagojejunostomy and Roux-en-Y anastomosis should be considered.1 While these procedures allow diversion of bilio-pancreatic secretions away from the oesophagus and the gastric stump, symptomatic acid reflux and volume regurgitation may persist in the presence of a mechanically defective lower oesophageal sphincter with hiatus hernia.

Laparoscopic-assisted Roux-en-Y procedures are usually technically demanding and time-consuming due to the presence of extensive intra-abdominal adhesions and the need of disconnecting the afferent jejunal loop. The MSA (LINX) system, approved by FDA in 2012, consists of a series of titanium beads with magnetic cores sealed inside. The beads are connected with independent titanium wires to form a flexible ring which is expandable and does not limit the range of motion of the oesophagus on swallowing, belching and vomiting. The MSA device, first implanted in humans in 2007,3 has been primarily recommended for use in patients with typical GERD symptoms and small (<3 cm) hiatus hernia. The MSA procedure is designed for the laparoscopic approach and does not require division of short gastric vessels. Currently, MRI >1.5 Tesla represents a contraindication to the procedure. Several clinical studies have shown the safety and effectiveness of MSA both in single-arm and comparative studies with fundoplication.4–8 Device erosions have rarely occurred and have been managed without sequelae.9 10 More recently, the MSA procedure has been successfully performed in patients with large hiatus hernia11 and in those presenting de novo GERD after sleeve gastrectomy.12

MSA is a new and highly standardised surgical option for the treatment of refractory GERD after partial gastrectomy and Billroth II reconstruction. Compared with the classic Roux-en-Y anastomosis, MSA can be performed laparoscopically and can simultaneously correct acid and biliary reflux.

Learning points.

Combined bile and acid reflux occur in about one-third of patients after distal gastrectomy and Billroth II reconstruction.

Roux-en-Y conversion is the remedial operation of choice in patients with intractable reflux symptoms, but regurgitation and acid reflux may persist despite effective bile diversion due to a mechanically defective lower oesophageal sphincter.

Magnetic sphincter augmentation is a new available option in these patients and the procedure can safely be performed through a laparoscopic approach.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM, VL and EA: collected the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LB: revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Earlam R. Bile reflux and the Roux en Y anastomosis. Br J Surg 1983;70:393–7. 10.1002/bjs.1800700702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Csendes A, Burgos AM, Smok G, et al. . Latest results (12-21 years) of a prospective randomized study comparing Billroth II and Roux-en-Y anastomosis after a partial gastrectomy plus vagotomy in patients with duodenal ulcers. Ann Surg 2009;249:189–94. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181921aa1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonavina L, Saino GI, Bona D, et al. . Magnetic augmentation of the lower esophageal sphincter: results of a feasibility clinical trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:2133–40. 10.1007/s11605-008-0698-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonavina L, Saino G, Bona D, et al. . One hundred consecutive patients treated with magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease: 6 years of clinical experience from a single center. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:577–85. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Riegler M, Schoppman SF, Bonavina L, et al. . Magnetic sphincter augmentation and fundoplication for GERD in clinical practice: one-year results of a multicenter, prospective observational study. Surg Endosc 2015;29:1123–9. 10.1007/s00464-014-3772-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ganz RA, Edmundowicz SA, Taiganides PA, et al. . Long-term Outcomes of Patients Receiving a Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation Device for Gastroesophageal Reflux. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:671–7. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aiolfi A, Asti E, Bernardi D, et al. . Early results of magnetic sphincter augmentation versus fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2018;52:82–8. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prakash D, Campbell B, Wajed S. Introduction into the NHS of magnetic sphincter augmentation: an innovative surgical therapy for reflux - results and challenges. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2018;100:251–6. 10.1308/rcsann.2017.0224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Asti E, Siboni S, Lazzari V, et al. . Removal of the Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation Device: Surgical Technique and Results of a Single-center Cohort Study. Ann Surg 2017;265:941–5. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith CD, Ganz RA, Lipham JC, et al. . Lower Esophageal Sphincter Augmentation for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: The Safety of a Modern Implant. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2017;27:586–91. 10.1089/lap.2017.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buckley FP, Bell RCW, Freeman K, et al. . Favorable results from a prospective evaluation of 200 patients with large hiatal hernias undergoing LINX magnetic sphincter augmentation. Surg Endosc 2018;32:1762–8. 10.1007/s00464-017-5859-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawasli A, Tarakji M, Tarboush M. Laparoscopic management of severe reflux after sleeve gastrectomy using the LINX® system: Technique and one year follow up case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017;30:148–51. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.11.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]