Abstract

We present a rare and interesting case of a 35-year-old woman who initially underwent an uneventful wide excision for a 13 cm left benign phyllodes tumour. She then noted a slowly growing left thyroid nodule 8 months postsurgery which on thyroidectomy 4 years later was shown to be a 6.9cm isolated thyroid metastasis from the phyllodes tumour. As this may be the first reported such case in the literature, implications on histological classification, predictive factors for disease progression, mechanisms of metastasis, and evaluation, management and surveillance of benign phyllodes tumours and thyroid nodule/s with a history of phyllodes tumour can thus be significantly impacted.

Keywords: breast surgery, oncology, breast cancer

Background

Phyllodes tumours of the breast are classified microscopically as benign (low grade), borderline or malignant (high grade) based on mitotic activity, stromal atypia and cellularity, tumour margin infiltration and stromal overgrowth,1 with the malignant variety generally associated with a higher risk of recurrence, metastasis and more aggressive clinical behaviour. Although factors other than histological grade can influence the clinical course of patients with phyllodes tumour, the treatment consensus of considering adjuvant radiation therapy for borderline or malignant cases, chemotherapy for large, high-risk, or recurrent malignant tumours and acceptance of a narrower (<1 cm) margin for benign tumours2 reflect on the impact of histological classification on the total management of phyllodes tumours. Overall, distant metastasis is said to be uncommon, occurring nearly exclusively in malignant phyllodes tumours at a rate of 9%–27%, mostly in the lungs, bone, brain and liver. In a recent summary of studies on metastatic phyllodes tumours published last year, only 7 out of 1915 benign phyllodes tumours (0.37%) had distant metastasis.3 Thyroid as a site of metastasis was reported in only 1 case of malignant phyllodes tumour in a patient with local recurrence and multiple sites of metastasis including the lungs, stomach, small intestine and spleen.4 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an isolated thyroid metastasis from a benign phyllodes tumour in the literature and therefore not only serves as a worthy addition to our limited body of knowledge and understanding of this relatively rare tumour, but can also inspire research and ultimately influence significantly our overall management of benign phyllodes tumours and patients with thyroid nodules and a history of phyllodes tumour.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old otherwise healthy Asian woman first presented with a 10-year duration of a slowly growing left breast mass. Physical examination revealed a 13×10 cm, multilobular, firm, movable left breast mass with skin ulceration over the upper outer quadrant and three firm, movable right breast masses measuring 2–2.5 cm each. She then underwent an uneventful excision of right breast masses and a left total mastectomy with primary closure. Histopathology report showed fibroadenomata, right breast and phyllodes tumour, low grade (benign), 13 cm in greatest dimension with skin ulceration and negative margins of resection, left breast. Microscopic description from multiple sections included a phyllodes tumour with stromal proliferation compressing ducts into leaf-like structures lined by columnar and myoepithelial cells and focal mild atypia with mitotic count ranging from 1 to 3 per 10 high power fields (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Benign phyllodes tumour with mild cellularity and absent to minimal stromal atypia (400×, H&E).

Patient remained asymptomatic until 8 months postsurgery when she complained of a left anterior neck mass. Neck ultrasonography demonstrated an isoechoic solid lower left thyroid nodule measuring 2.5×1.8×1.6 cm. Thyroid functions tests (T3, T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone) were within normal limits. Further work-up and management were advised. However, patient was lost to follow-up for the next 4 years. Five years and 5 months postsurgery, our now 40-year-old patient followed up generally asymptomatic except for the enlarging, firm and movable left thyroid lobe measuring 6×4 cm.

The patient is nulligravid and a housewife. The rest of her past medical, social, family and gynecological history is unremarkable.

Investigations

Ultrasonography of the neck revealed a normal-sized right thyroid lobe and isthmus and an enlarged left thyroid lobe now measuring 6.9×4.4×4.3 cm with a large, poorly marginated, non-calcified, predominantly solid heterogeneous isoechoic complex mass with intervening cystic foci within. Chest X-ray, blood counts, serum chemistries and thyroid function tests were within normal limits.

Differential diagnosis

Primary impression for the left thyroid mass was colloid adenomatous goitre based on incidence, a 4-year course and physical examination and ultrasonographic findings of a complex mass. Differential diagnoses would include other thyroid pathologies such as benign or malignant follicular neoplasm and medullary carcinoma. Less likely considerations include papillary carcinoma due to its more solid and hard consistency, and isolated metastatic disease to the thyroid due mainly to its extreme infrequency, the benign nature of the patient’s previous phyllodes tumour and no other associated masses such as a local chest recurrence.

Treatment

She initially underwent left total lobectomy, isthmusectomy and pyramidalectomy with frozen section examination diagnosis of poorly differentiated neoplasm with spindle, myxoid and clear cell features involving thyroid and a consideration of medullary carcinoma. Definitive diagnosis was deferred pending permanent paraffin sections and immunohistochemistry studies. A total thyroidectomy was eventually done with final histopathology findings of a malignant phyllodes tumour composed of lobules of loosely arranged spindly stromal cells amidst an oedematous myxoid background with marked cellularity, stromal overgrowth and heterologous elements infiltrating the 200 gm left thyroid lobe measuring 9×7.5×6.5 cm and presence of vascular invasion, occasional mitotic figures, focal necrosis and haemorrhages (figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining with thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) done showed TTF-1 positive (+) thyroid tissue infiltrated by a TTF-1 negative (−) tumour implicating a metastatic tumour rather than a primary thyroid neoplasm (figure 3).

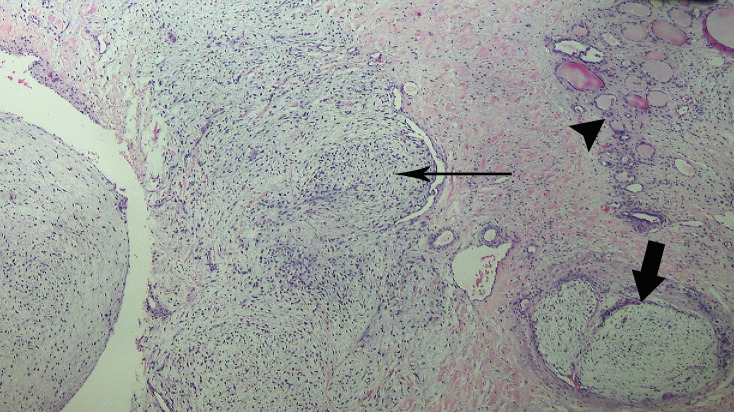

Figure 2.

Phyllodes tumour infiltrating non-neoplastic thyroid. Arrowhead pointing to thyroid tissue. Long arrow pointing to tumour with marked cellularity and stromal overgrowth. Short block arrow pointing to tumour with mild cellularity (100×, H&E).

Figure 3.

TTF-1 positive (+) thyroid tissue infiltrated by TTF-1 negative (−) tumour. TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor 1 (100 ×, Immunohistochemistry horseradish peroxidase method).

Outcome and follow-up

Immediate postoperative course was generally unremarkable while a whole body bone/SPECT-CT scan done revealed no evident bone, lung, liver, brain or lymph node metastasis. The patient was doing well on oral thyroid hormone replacement therapy on at least two out-patient follow-up visits, the last being 5 weeks post-op, when exactly 8 weeks post-op, she was reported by a relative to have suddenly fallen and found dead on a usual day walk in her backyard.

Discussion

The case presented is unique when viewed from several perspectives. First, benign phyllodes tumours rarely metastasize, giving credence to the term ‘benign’ as against its ‘malignant’ counterpart, and if at all, metastasis is usually to the lungs. This case puts emphasis on the misnomer that benign phyllodes tumours do not metastasize. Thus, a better understanding of the biology of phyllodes tumour is imperative to adequately predict likelihood of metastasis. Perhaps the use of biomarkers to predict metastatic potential may provide a better approach to the management of benign or low-grade phyllodes tumours as against the usual reliance on histological features, although in a recent review on the use of molecular features such as Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), c-kit, Wingless-related integration site (Wnt) and insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein-3 (IMP3)5 expression, results have been conflicting.6

Second, cancer metastasis to the thyroid is likewise uncommon, with reported incidence of 0.5%7 to 24%8 in those with widespread metastatic disease and constituting <1% of all thyroid malignancies.9 Carcinoma of the breast has been reported to metastasize to the thyroid in a series of seven patients.10 Thyroid metastasis arising from all sarcomas is exceedingly rare. Until 2012, only about 20 cases of sarcomas metastatic to the thyroid gland have been reported in the literature,11 12 with one coming from malignant phyllodes tumour associated with metastases to other organs.7 Since then, thyroid metastasis from malignant fibrous histiocytoma,10 dermatofibrosarcoma,12 rhabdomyosarcoma13 and cardiac sarcoma14 have been reported. Moreover, of 28 documented cases in the literature of tumour-to-tumour metastasis to thyroid neoplasms, such as follicular adenomas and papillary carcinomas, only 1 came from a malignant phyllodes tumour and only 15% (3/20 cases available for determination) were isolated to the thyroid neoplasm,15 which is another (the third) unusual angle of the case presented, that of the normal, rather than neoplastic, thyroid being the only site of metastasis, as proven by the negative bone/SPECT CT scan. Furthermore, a solitary or isolated site of metastasis from a lone previous tumour site is consistent with a true metastasis from benign phyllodes tumour rather than in a case wherein there is concurrent local recurrence with malignant transformation, as it can then be argued that the metastasis could have come from the malignant local recurrence.

Fourth, even as our patient presented with over a 5-year duration of a slowly growing thyroid nodule first noted 8 months postsurgery for benign phyllodes tumour, a primary impression of metastatic phyllodes tumour to the thyroid is highly unlikely since even in patients with a clinical history of malignancy, a new thyroid nodule is still likely to be a benign lesion,16 more so in underdeveloped and inland areas of the Philippines where benign colloid adenomatous goitre may still be considered endemic.

Finally, this case illustrates further that the subtype of phyllodes tumour alone, either malignant or benign, does not adequately predict biological behaviour and risk of recurrence.17 And even as the outcome of treatment in metastatic phyllodes tumours remains dismal, the recognition of metastasis to the thyroid can influence proper oncological management and even appropriate surgical approach. And with research advances especially in the area of adjuvant therapy, it is with fervent hope that with the knowledge of which variant of phyllodes tumour to treat postsurgically, we can decrease or even totally prevent the risk of metastasis.

Learning points.

Benign phyllodes tumours can metastasize although very rarely (<1%). Most metastasis occur in the lungs as in malignant phyllodes tumours.

The thyroid gland can be a site of metastasis of soft tissue sarcomas and phyllodes tumours, either as part of multiorgan involvement, or isolated, as in the case presented.

Known clinicopathological factors such as stromal overgrowth, cellularity, atypia and mitotic activity do not adequately predict biological behaviour and metastatic potential of both malignant and benign variants of phyllodes tumours.

There is a need for more research and identification of other biological and therapeutic aspects of metastatic phyllodes tumours to improve survival.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Dr. Mark Anthony Sandoval for his motivational and logistical support; Dr. Jun Carnate for his brilliant editing of the figures and captions presented; Dr. Hian Ho Kua for his administrative support; Ms. Angel Varde for her indispensable aid in documentation and Markyn Jared Kho for his technical expertise and inspiration.

Footnotes

Contributors: MRK: designed, conceptualised, gathered all data, drafted and wrote the case report; did the review of literature and is the corresponding author and guarantor. ADA: is responsible for the interpretation and reporting of all the pathological examinations done; reviewed all the specimen slides, carefully selected and obtained images then composed appropriate figure captions; vital participation in the overall planning, analysing, writing and critical revisions of the manuscript was imperative during periodic discussions held throughout the preparation of this manuscript. Both authors approved the final version for consideration for publication and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Next of kin consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al. (). WHO classification of tumours of the breast. 4th edn Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grau AM, Chakravarthy AB, Chugh R. Phyllodes tumors of the breast. Uptodate September 2017. 2017. http://www.uptodate.com

- 3.Koh VCY, Thike AA, Tan PH. Distant metastases in phyllodes tumours of the breast: an overview. Applied Cancer Research 2017;37:15 10.1186/s41241-017-0028-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward RM, Evans HL. Cystosarcoma phyllodes. A clinicopathologic study of 26 cases. Cancer 1986;58:2282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takizawa K, Yamamoto H, Taguchi K, et al. Insulin-like growth factor II messenger RNA-binding protein-3 is an indicator of malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast. Hum Pathol 2016;55:30–8. 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitaleri G, Toesca A, Botteri E, et al. Breast phyllodes tumor: a review of literature and a single center retrospective series analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013;88:427–36. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam KY, Lo CY. Metastatic tumors of the thyroid gland: a study of 79 cases in Chinese patients. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998;122:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakhjavani MK, Gharib H, Goellner JR, et al. Metastasis to the thyroid gland. A report of 43 cases. Cancer 1997;79:574–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virk RK, Barkan GA. Metastatic tumors to the thyroid: a review with focus on cytology. AJSP: Reviews & Reports 2015;20:218–22. 10.1097/PCR.0000000000000106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saber A, Ramzy S, Gouda I. Metastasis to the thyroid gland; unusual site of metastasis. Gulf J Oncolog 2007;1:51–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giorgadze T, Ward RM, Baloch ZW, et al. Phyllodes tumor metastatic to thyroid Hürthle cell adenoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:1233–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreze A, Zápotocká A, Urbanec T, et al. Metastasis of dermatofibrosarcoma from the abdominal wall to the thyroid gland: case report. Case Rep Med 2012;2012:1–4. 10.1155/2012/659654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafez MT, Hegazy MA, Abd Elwahab K, et al. Metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma of the thyroid gland, a case report. Head Neck Oncol 2012;4:27 10.1186/1758-3284-4-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yesodharan J, Kandamuthan S, Poothiode U. Primary cardiac sarcoma with metastases to thyroid and brain. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2015;58:345–7. 10.4103/0377-4929.162870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens TM, Richards AT, Bewtra C, et al. Tumors metastatic to thyroid neoplasms: a case report and review of the literature. Patholog Res Int 2011;2011:1–5. 10.4061/2011/238693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koo HL, Jang J, Hong SJ, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to follicular adenoma of the thyroid gland. a case report. Acta Cytol 2004;48:64–8. 10.1159/000326285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology breast cancer version. 2017. http://www.nccn.org