Abstract

Objective:

To report long-term follow-up of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) and nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NF-PET).

Background:

Pancreaticoduodenal tumors occur in almost all patients with MEN1 and are a major cause of death. The natural history and clinical outcome are poorly defined, and management is still controversial for small NF-PET.

Methods:

Clinical outcome and tumor progression were analyzed in 46 patients with MEN1 with 2 cm or smaller NF-PET who did not have surgery at the time of initial diagnosis. Survival data were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results:

Forty-six patients with MEN1 were followed prospectively for 10.7 ± 4.2 (mean ± standard deviation) years. One patient was lost to follow-up and 1 died from a cause unrelated to MEN1. Twenty-eight patients had stable disease and 16 showed significant progression of pancreaticoduodenal involvement, indicated by increase in size or number of tumors, development of a hypersecretion syndrome, need for surgery (7 patients), and death from metastatic NF-PET (1 patient). The mean event-free survival was 13.9 ± 1.1 years after NF-PET diagnosis. At last follow-up, none of the living patients who had undergone surgery or follow-up had evidence of metastases on imaging studies.

Conclusions:

Our study shows that conservative management for patients with MEN1 with NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller is associated with a low risk of disease-specific mortality. The decision to recommend surgery to prevent tumor spread should be balanced with operative mortality and morbidity, and patients should be informed about the risk-benefit ratio of conservative versus aggressive management when the NF-PET represents an intermediate risk.

Keywords: long-term follow-up, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, surgery

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is an autosomal dominant disease that predisposes patients to develop different endocrine tumors, mainly of the pituitary gland (micro- or macroadenoma, functioning or not), the parathyroid glands (primary hyperparathyroidism), and the endocrine pancreas (endocrine tumors of the duodenum and pancreas, functioning or not). Pancreaticoduodenal tumors are a major cause of premature death in patients with MEN1.1,2 Standardized detection and follow-up protocols have shown that almost all patients with MEN1 will develop pancreaticoduodenal tumors at some point during their life.3–5 Moreover, because these protocols include high-performance imaging studies, pancreaticoduodenal tumors are being discovered early in the course of disease. Many small (<1–2 cm) pancreaticoduodenal tumors are detected during routine follow-up in patients with MEN1, raising the controversy as to whether surgery should be performed on patients with small tumors.6

Although most published studies conclude that surgical resection should be done for insulinoma, vasoactive intestinal peptide secreting tumor (VIPoma), glucagonoma, and somatostatinoma, the management of small nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (NF-PET) is highly controversial. Some authors recommend an aggressive resection as soon as a tumor is identified but others recommend more conservative management of small tumors, which are variously defined as less than 1 cm, less than 1.5 cm, or 2 cm or smaller.7–13

Our previous studies have shown that the risk of developing lymph node and/or distant metastases correlates with the size of the primary tumor, and that the risk of death was low for patients with MEN1 with small (≤2 cm) NF-PET.14,15 In these studies, 5 (7.7%) of 65 patients with NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller had synchronous lymph node or distant metastases and 2 (3.0%) surgical patients died of the disease. Furthermore, the overall survival of patients with MEN1 with NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller was similar to the survival of patients with MEN1 without pancreaticoduodenal involvement.14 Because of these favorable results, we proposed a conservative approach for patients with MEN1 who present with NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller that do not have aggressive features.14,15 These studies, however, had 2 important limitations. The first was a short mean follow-up time of 3.3 ± 2.6 years for patients who did not have surgery. The second was that metastasis detection is always lower with imaging studies [Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] than with surgery and pathological evaluation. Consequently, some experts doubted the low risk of metastasis we reported and feared that with time, many lymph node and/or distant metastases would appear in the patients who did not have initial surgery.

For all these reasons, we conducted a prospective, long-term follow-up study of the same cohort of patients with MEN1 with small NF-PET who had not undergone surgery during the initial follow-up period.

METHODS

Data Collection and Analysis

A task of the Groupe d’Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines (GTE; French Endocrine Tumor Study Group) is to maintain a registry of patients with MEN1 at the Center for Epidemiology of the Population at the University of Bourgogne in Dijon, France, receiving reports on patients with MEN1 from 5 French and Belgium laboratories accredited for genetic testing of MEN1 and also from primary care physicians. Registry data for patients with MEN1 include results of genetic testing, clinic visit reports, operative reports, pathology reports, and hospital discharge summaries.2,16

The MEN1 cohort was approved by the Consultative Committee on Treatment of Information in Health Research (file number 12.364) and the CNIL (National Committee for Data Protection, authorization number DR 2013-348). Informed consent was not required, but patients were informed about their right to withdraw their data from the cohort.

We selected all patients with MEN1 diagnosed with NF-PET between June 1956 and April 2003 included in the GTE registry, as previously described.15 Briefly, NF-PET was diagnosed when 1 or more pancreatic solid nodules were identified by any imaging studies and after excluding gastrinomas, insulinomas, glucagonomas, VIPomas, or somatostatinomas. A total of 108 patients with NF-PET were identified among 579 patients with MEN1 included in the registry at the time of our previous study.14,15 Sixty-five of them had NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller of which 50 did not have surgery during the initial follow-up period. These 50 patients comprise the present study cohort.

Follow-up procedures consisted of sequential imaging and laboratory studies. The type and frequency of imaging studies performed varied among centers and according to the patient's disease course, but included at least an imaging study every 3 years (EUS, CT, or MRI).

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean values ± standard deviation unless stated otherwise. Event-free survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. For survival analysis, data are expressed as the time from NF-PET diagnosis to the end of follow-up (at last pancreatic imaging and biochemical analyses) or death. Death, surgery, increase in size, or development of hypersecretion were considered progression of the pancreaticoduodenal involvement and as “events” in the Kaplan-Meier curves. Statistical analyses were performed and graphs generated with SPSS software version 23.0.0.0 for MAC (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Legends and numbers of patients at risk were added to the graphs using Adobe Photoshop CC2015.1.1 (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

At the end of our 2003 study of 50 patients with NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller who had not had surgery,14,15 1 patient had died of thymic tumor and 3 were lost to follow-up. This resulted in a cohort of 46 patients with a total follow-up time of 10.7 ± 4.2 years (from the date of NF-PET diagnosis to the end of this present study). The follow-up interval from the end of our previous study to the end of the present study is 7.7 ± 3.1 years.

At the time of NF-PET diagnosis, patients were 39.9 ± 13.6 years old and presented with 96 pancreatic tumors (2.3 ± 1.9 tumors/patient) averaging 9.3 ± 5.0 mm. These tumors were identified in 21 patients by CT, in 17 by EUS, in 5 by MRI, and in 3 by unknown imaging studies.

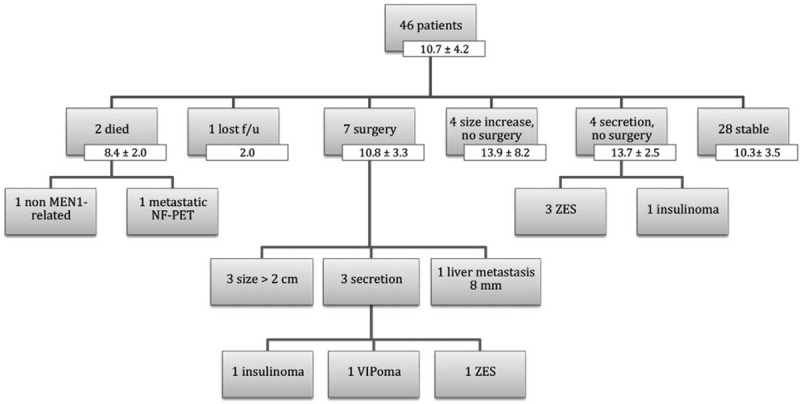

One patient was lost to follow-up (alive with 4 NF-PET, the largest was 1.7 cm after 2 yr of additional follow-up), and the 45 other patients were still being followed at the end of the present study (Fig. 1). One of these 45 patients died of a cause unrelated to MEN1 at age 76. Another patient died of metastatic NF-PET at age 67. Initially, at age 57, he had an elevated pancreatic polypeptide (PP) level (1432 pg/mL) without evidence of a pancreatic tumor on CT and EUS (although patient morphology made it difficult to analyze the imaging studies). At the age of 60, the patient had an increase in PP to 2287 pg/mL and a CT scan was still described as normal. Then at the age of 63, the PP was stable but EUS showed 3 pancreatic tumors of 3, 5, and 7 mm. One year later, EUS and CT showed 5 NF-PET with a maximum size of 16 mm and numerous hepatic masses, confirmed to be of endocrine nature on biopsy (maximum size 4.3 cm). He died 3 years later of disease progression after multiple regimens of chemotherapy.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study cohort with number of patients and mean follow-up times of the entire cohort and of the subgroups (years ± standard deviation). F/u indicates follow-up.

Long-term Outcomes

Seven patients (15.2%) underwent surgery after initial conservative management at 5.9 ± 4.7 years of follow-up (Table 1, Fig. 1). The indication for surgery was an increase in size of the largest tumor over 2 cm for 3 patients; hypersecretion for 3 patients [1 with insulinoma, 1 with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES), and 1 with VIPoma], and for 1 patient, development of a single hepatic metastasis that led to a combined pancreatic + liver resection. The patient with ZES was initially managed medically, but later underwent surgery (Whipple procedure) for an intestinal perforation that developed while the patient was on proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. In 2 patients, preoperatively unidentified lymph node metastases were found at pathological evaluation (1 in the patient with ZES and 1 in a patient with a 25 mm NF-PET; patients 2 and 3 in Table 1). After a postoperative follow-up time of 5.0 ± 2.4 years, these 7 patients are considered “oncologically cured,” although 3 patients have new NF-PET on imaging studies and the patient with ZES is still receiving treatment with PPI; his hypergastrinemia is well controlled.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 Patients Who Underwent Surgery

| Patient | Age at NF-PET Diagnosis (yr) | Interval to Surgery (yr) | Indication for Surgery | Surgery | f/u After Surgery (yr) | Last f/u |

| 1 | 51.2 | 9.1 | Increase in size (max 29 mm) | DSP | 6.3 | 2 New NF-PET (max 4 mm) PP normal, NIDDM |

| 2 | 34.1 | 11.5 | Increase in size (max 25 mm) | Whipple + enucleation, 1LN + /7LN | 3.4 | 3 NF-PET (max 15 mm), no evidence of LN or distant mets |

| 3 | 49.4 | 11.2 | ZES, NF-PET stable in size | Whipple (4 gastrinoma, 1LN + /1LN) | 1.2 | Persistent hypergastrinemia, no evidence of LN or distant metastasis |

| 4 | 30.4 | 4.8 | Symptomatic VIPoma | DSP + enucleation | 3.9 | NIDDM, biochemically cured of VIPoma, no evidence of tumor on MRI |

| 5 | 59.3 | 3.2 | Hepatic metastasis (8 mm) | DSP + enucleation + left hepatic lobectomy 0LN + /6LN | 5.1 | No evidence of tumor on CT |

| 6 | 42.5 | 1.0 | Increase in size (max 25 mm) | Body + tail resection | 8.3 | 3 new NF-PET (max 4 mm), PP normal |

| 7 | 36.2 | 1.0 | Insulinoma + increase in size (max 22 mm) | Body + tail resection + enucleation of 8 tumors | 6.8 | NIDDM, biochemically cured of insulinoma, no new tumor on MRI |

Number of positive LN/number of resected LN.

DSP indicates distal splenopancreatectomy; f/u, follow-up; LN, lymph node; max, maximum size; NIDDM, non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Of the 39 patients in the nonsurgical cohort (Fig. 1), 4 (8.7%) had a significant increase in the size (7.5 ± 4.5 mm) of their NF-PET after a follow-up time of 13.9 ± 5.2 years but did not undergo surgery. In 4 patients (8.7%) a hypersecretion developed after a follow-up time of 13.7 ± 2.5 years. Three patients had ZES with tumors of less than 1 cm detected on imaging studies; their symptoms are well controlled with PPI therapy. One patient, a 35-year-old with hyperinsulinism and 4 pancreatic nodules identified on EUS (largest 11 mm) is currently receiving somatostatin analogs and does not wish to have surgery.

Twenty-eight of the 46 patients (60.9%) have clinically stable disease after 10.3 ± 3.5 years of follow-up. At the beginning of their pancreaticoduodenal MEN1-associated disease, these patients presented with an average of 2.3 ± 1.8 lesions per patient; maximum size of 10.6 ± 4.5 mm (total, 61 lesions). At the end of follow-up, these patients had an average of 2.9 ± 2.3 lesions per patient; maximum size of 10.9 ± 3.8 mm (total, 79 lesions).

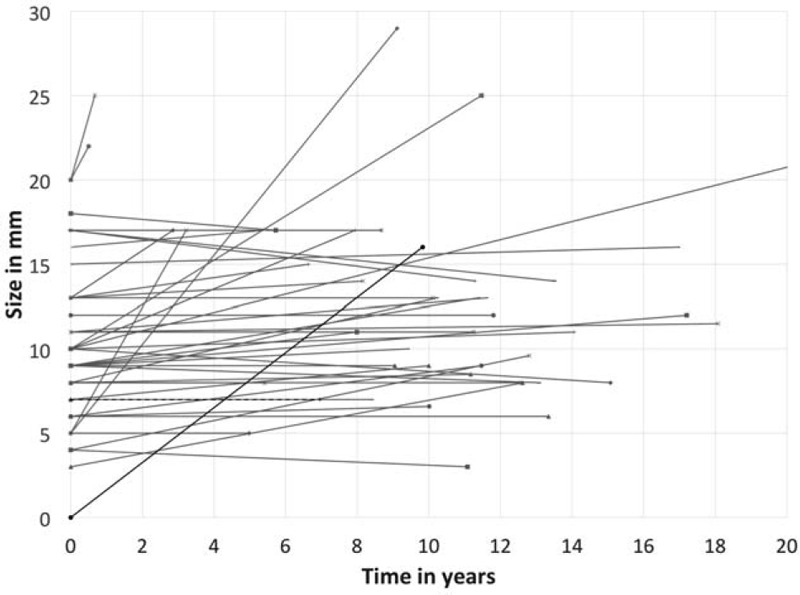

The changes in the diameter of the initially diagnosed NF-PET are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Follow-up of growth of NF-PET in mm, as a function of time in years represented graphically. Time was defined until date of last follow-up, or time until surgery for patients who underwent surgery. Patients who underwent surgery are represented by red lines, patients who were followed clinically by blue lines, the patient who died from MEN1 disease by a black line, the patient who died of a non–MEN1-related cause by a dashed black line, and the patient lost to follow-up by a green line.

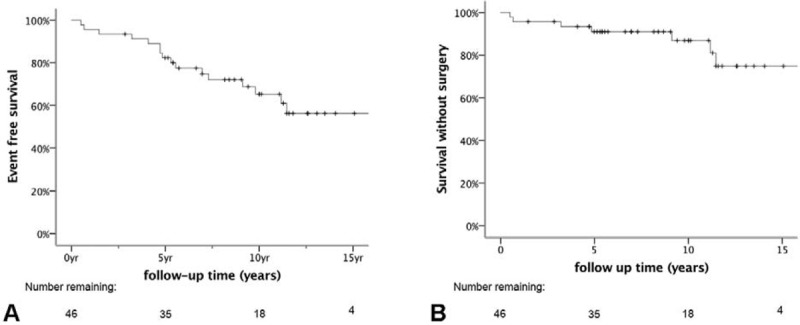

Overall event-free survival of the entire cohort, for which surgery, increase in size or secretion, and death were all considered events, was 13.9 ± 1.1 years (Fig. 3A). Surgery-free survival of the entire cohort, with surgery defined as an event, was 16.6 ± 1.0 years (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier representation of event-free survival curves after NF-PET diagnosis. A, Overall event-free survival of entire cohort, including surgery, increase in size or secretion, and death as events. B, Surgery-free survival of the entire cohort, in which surgery is defined as the event. The number of patients at risk at each time point is shown below the graphs.

At the time of last follow-up, all 45 patients had MEN1-associated primary hyperparathyroidism. Five patients had nonsurgical therapy, 31 had surgery once, 7 had surgery twice, and 2 patients had surgery 3 times. Twenty-eight patients had MEN1-associated pituitary disease: 18 had nonsurgical therapy (13 with prolactinomas, 4 with nonsecreting adenomas, and 1 with growth hormone adenoma) and 10 had surgery for their pituitary disease (4 with prolactinomas, 4 with nonsecreting macroadenomas, and 2 with Cushing disease, 1 of whom finally underwent bilateral adrenalectomy for recurrent Cushing disease after hypophysectomy). Thirteen patients had adrenal disease: 9 had nonresected adrenal cortical adenoma, 2 had their cortical adenomas resected, and 2 had adrenal Cushing adenomas resected. Three patients developed lung carcinoids (surgical management in 1 patient, follow-up only in the 2 others). Only 1 patient had none of the common MEN1-associated diseases at last follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This prospective follow-up study of the same cohort of patients with MEN1 with small NF-PET who had not undergone surgery during the initial follow-up period15 extended the follow-up interval of the original study by 7.7 ± 3.1 years, for an average of 10.7 ± 4.2 years. This long-term study shows that 60.9% of patients continued to have stable disease, whereas only 39.1% show significant progression of pancreaticoduodenal involvement (either increase in size or number of tumors and/or development of a hypersecretion syndrome). Sixteen percent of patients underwent pancreaticoduodenal surgery and only 1 patient (2.2%) died of metastatic NF-PET. Furthermore, none of the alive patients presented with metastases at the last follow-up visit. To our knowledge, this is the largest study of patients with MEN1-associated NF-PET who did not have initial surgery at diagnosis and who had a mean follow-up time of more than 10 years.

The treatment strategy for small NF-PET in patients with MEN1 remains controversial. Pancreaticoduodenal tumors continue to be a significant cause of death in patients with MEN1, even though the endocrine-related causes of death (e.g., gastric or intestinal perforations due to ZES) are becoming very rare because of effective medical therapies.1,2,17–19 Neuroendocrine thymic tumors are another major cause of death in patients with MEN1, particularly in male smokers and justify specific investigations and follow-up.1,2,20 When current recommendations for screening of patients with MEN1 3 are followed and more sensitive imaging methods are used,21,22 most patients with MEN1 will show pancreatic involvement during their lives, making these tumors a clinically relevant problem for every patient with MEN1. Our previous study showed that 53% of 134 patients diagnosed with MEN1 since 1997 had pancreaticoduodenal tumors at age 50 and 84% had tumors at age 80.15 One study,23 however, demonstrated that patients with MEN1 had multiple “precursor” tumors (microadenomatosis) not yet identified by imaging, confirming that using more sensitive imaging techniques will show an increase of their penetrance.24 For instance, in a screening program for patients with MEN1 using CT, MRI, and EUS, a penetrance of 42% was found in patients ages 12 to 20,25 which is much higher than 10% at age 20 in our previous study.15 Moreover, most of these small tumors progress slowly over time, estimated as a mean increase of 15% of the largest tumor size per year in one study,26 and one third of patients will have a significant increase in size and/or number of tumors during 5 years, as suggested by one of our previous GTE studies.4

For patients with MEN1 with small NF-PET, several groups suggest that surgical resection be considered when tumors are more than 1 cm in size (Thakker et al,3 the Uppsala group,27 the Marburg group,9 and the MEN consortium in Japan28). The NIH group and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in the United States suggest a more conservative approach for tumors 1 to 2 cm.29–31 Similarly, the GTE recommends conservative management of NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller if there are no signs of aggressiveness, such as rapid progression on imaging studies.4,14 A recent European multicenter study12 concluded that surgical treatment of NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller at initial diagnosis is rarely justified, similar to the ENETS Consensus guidelines.13 The DutchMEN1 Study Group also recently analyzed data from 152 patients with MEN1 who were diagnosed with NF-PET. Using time-dependent Cox analysis with propensity score adjustment, they reported that after a median follow-up of 5.4 years, surgery was not associated with a significant lower risk of NF-PET liver metastases or death and concluded that the majority of patients with MEN1 with small NF-PET can safely be managed by watchful waiting, thereby avoiding major surgery without loss of oncological safety. (S. Nell et al, oral presentation held during the WorldMEN Congress in Utrecht in October 2016).

The treatment approach for patients with MEN1 with small NF-PET warrants comparison with the approach for sporadic small NF-PET, for which several recent studies recommend nonsurgical management with clinical follow-up because no metastases or death have occurred among patients who had observation only.32–34 In those studies, the 2 cm cutoff for recommending surgery was followed, although 1 study showed better prediction of malignancy when a 1.7 cm cutoff for surgical management was used.35 The reported incidence of lymph node metastases is low in sporadic, small G1 NF-PET, further confirming that surveillance only is a safe approach.36,37

Series from large centers have reported a very low or even 0% mortality rates from pancreaticoduodenal surgery in patients with MEN1, but limited data are available on long-term complications, disabilities, and quality of life after pancreaticoduodenal surgery in these patients. First, a study from the University of Michigan38 reported that with aggressive management with the “Thompson procedure” (left pancreatectomy and enucleation for head lesions, together with a duodenotomy in the case of ZES), 15 of 39 patients (38%) needed one or more reoperations for disease persistence or recurrence during follow-up. Over a median follow-up time of 6 years, 30 additional surgeries were performed with a median interval time of 4 years between the different surgeries. Two patients died during follow-up because of metastatic pancreatic NET despite an aggressive management protocol consisting of repeated surgeries when pancreatic tumors were identified. Ten (47%) patients had insulin-dependent diabetes and 7 (33%) needed oral medication for diabetes. Moreover, 4 patients (20%) had significant disability and were unable to return to work. Second, a follow-up study of the same University of Michigan series from 1979 to 2008 showed that 8 of 49 patients needed completion pancreatectomy and duodenectomy; median follow-up was 12 years and a median of 2 additional surgeries were reported.39 There were 7 complications related to surgery, including 1 death after enterocutaneous fistula and 3 patients who required insulin pumps to treat postoperative diabetes. The results of both studies from the University of Michigan38,39 demonstrate that despite aggressive management, disease-specific deaths were not totally prevented and long-term morbidity was significant, even if immediate postoperative mortality was low. Third, in a series of 20 patients, postoperative morbidity occurred in 7 (35%) after pancreaticoduodenectomy and 40% of patients showed long-term endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after a median follow-up time of 3 years.40 Fourth, in a series of 38 patients with MEN1 who had duodenopancreatic resections, 10 (26%) underwent up to 4 reoperations for either recurrent or metastatic disease. Postoperative morbidity occurred in 18 (47%) patients after initial surgery, and in 4 (10%) patients after reoperation (pancreatic fistula in 13 of 36 patients and postoperative diabetes mellitus in 4 patients). After a median follow-up of 109 (range 1–264) months, 35 patients (92%) were alive, all 8 patients with insulinoma and 7 of 13 patients with ZES were biochemically cured, and liver metastases did not develop in any patient during follow-up. The 10-year survival rate was 87% for ZES, 87% for insulinoma, and 100% for NF-PET. Twenty-four of 38 (63%) patients developed new PET in the pancreatic remnant after a median of 109 months, which led to resection of the pancreatic remnant in 3 (8%) patients.10 These results show that PET, either functioning or nonfunctioning will appear in patients with MEN1 as long as pancreatic tissue is left in place. Finally, in a recently published multicenter series from the DutchMEN1 group, 19 of 58 patients (33%) who underwent pancreaticoduodenal surgery for NF-PET at academic centers developed major early complications and 14 (23%) developed long-term endocrine and/or exocrine insufficiency.41 One patient died 30 days after surgery and 2 patients became permanently disabled.

The main limitation of the present study is the multicenter design with heterogeneous clinical management and imaging follow-up among centers, which might have biased the uniformity of analyses. It is therefore not possible from the present study to make clear recommendations on the type of imaging study and laboratory testing that should be performed during follow-up. We can, however, suggest that for patients with stable disease and no sign of aggressiveness, an imaging study should be done every 2 to 3 years. We previously showed that EUS and MRI are complementary investigations for the detection of pancreatic tumors in patients with MEN1,42 and that EUS detects more tumors, as confirmed by others.21 MRI, however, detected more large (>2 cm) tumors in our study.42 A specific study evaluating the ability of both techniques in detecting tumor growth during follow-up has not been done yet. Hence, the choice of imaging study to be used remains debatable. Because all tumors bigger than 1 cm are easily detectable with MRI, using it instead of EUS should be evaluated. In our opinion, MRI is the first imaging technique to be used to detect and follow NF-PET in patients with MEN1 because unlike EUS, it is not invasive or require general anesthesia, unlike CT, it is not irradiating, and, according to our recommendations to follow small NF-PET without surgery, we do not need to find those very small tumors that would probably be more visible on EUS.

Another limitation of the present study is the definition of “disease progression.” We chose to study the patients and the duodenopancreas as a whole and therefore decided to include all events related to the duodenopancreas. We are aware that those events are not only related to the initial NF-PET but to the overall progression of the MEN1-related disease. For instance, the 3 patients who underwent surgery because of a hypersecretion syndrome most probably did not have progression of the initially identified NF-PET, but another, new tumor. To overcome this limitation, we have also shown the size progression of the initial tumor (Fig. 2), as others have done when monitoring NF-PET in patients with MEN1 with serial EUS.4,26

Future areas of research are that diagnosis and surveillance of PET in patients with MEN1 will involve high-quality imaging, such as EUS with fine needle aspiration or microbiopsies (allows for better grading classification than fine needle aspiration) or newer functional somatostatin receptor positron emission tomography (68Gallium).21,22,43 New prognostic markers have emerged such as DAXX-ATRX mutations to help stratify and select patients with potentially aggressive PET.44

In summary, our study demonstrates that conservative management for patients with MEN1 with NF-PET of 2 cm or smaller is associated with a low risk of disease-specific mortality, as only one of the patients died of progressive disease after 10.7 years of follow-up. The decision to recommend surgery to prevent tumor spread should be balanced against operative mortality and morbidity. This recommendation, however, should not be understood as an obligation, as each patient should be informed about the risk-benefit ratio of a conservative versus aggressive management and participate in the decision making when the NF-PET is considered to be of intermediate risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the AFCE and GTE members for their efforts in data collection and analysis for the registry. The authors thank Pamela Derish for very helpful editorial comments.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ito T, Igarashi H, Uehara H, et al. Causes of death and prognostic factors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: a prospective study: comparison of 106 MEN1/Zollinger-Ellison syndrome patients with 1613 literature MEN1 patients with or without pancreatic endocrine tumors. Medicine (Baltimore) 2013; 92:135–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goudet P, Murat A, Binquet C, et al. Risk factors and causes of death in MEN1 disease. A GTE (Groupe d’Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines) cohort study among 758 patients. World J Surg 2010; 34:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:2990–3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas-Marques L, Murat A, Delemer B, et al. Prospective endoscopic ultrasonographic evaluation of the frequency of nonfunctioning pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumors in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pieterman CR, Conemans EB, Dreijerink KM, et al. Thoracic and duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: natural history and function of menin in tumorigenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer 2014; 21:R121–R142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadowski SM, Triponez F. Management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in patients with MEN 1. Gland Surg 2015; 4:63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dralle H, Krohn SL, Karges W, et al. Surgery of resectable nonfunctioning neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors. World J Surg 2004; 28:1248–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartsch DK, Langer P, Wild A, et al. Pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: surgery or surveillance? Surgery 2000; 128:958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartsch DK, Fendrich V, Langer P, et al. Outcome of duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg 2005; 242:757–764. discussion 764–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez CL, Waldmann J, Fendrich V, et al. Long-term results of surgery for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms in patients with MEN1. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011; 396:1187–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez CL, Falconi M, Waldmann J, et al. Partial pancreaticoduodenectomy can provide cure for duodenal gastrinoma associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg 2013; 257:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Partelli S, Tamburrino D, Lopez C, et al. Active surveillance versus surgery of nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms ≤2 cm in MEN1 patients. Neuroendocrinology 2016; 103:779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2016; 103:153–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triponez F, Goudet P, Dosseh D, et al. Is surgery beneficial for MEN1 patients with small (< or = 2 cm), nonfunctioning pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumor? An analysis of 65 patients from the GTE. World J Surg 2006; 30:654–662. discussion 663–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triponez F, Dosseh D, Goudet P, et al. Epidemiology data on 108 MEN 1 patients from the GTE with isolated nonfunctioning tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg 2006; 243:265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goudet P, Bonithon-Kopp C, Murat A, et al. Gender-related differences in MEN1 lesion occurrence and diagnosis: a cohort study of 734 cases from the Groupe d’etude des Tumeurs Endocrines. Eur J Endocrinol 2011; 165:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson S, Teh BT, Davey KR, et al. Cause of death in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Surg 1993; 128:683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doherty GM, Olson JA, Frisella MM, et al. Lethality of multiple endocrine neoplasia type I. World J Surg 1998; 22:581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean PG, Van Heerden JA, Farley DR, et al. Are patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I prone to premature death? World J Surg 2000; 24:1437–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goudet P, Murat A, Cardot-Bauters C, et al. Thymic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: a comparative study on 21 cases among a series of 761 MEN1 from the GTE (Groupe des Tumeurs Endocrines). World J Surg 2009; 33:1197–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Asselt SJ, Brouwers AH, Van Dullemen HM, et al. EUS is superior for detection of pancreatic lesions compared with standard imaging in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:159.e2–167.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadowski SM, Millo C, Cottle-Delisle C, et al. Results of (68)Gallium-DOTATATE PET/CT scanning in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221:509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anlauf M, Schlenger R, Perren A, et al. Microadenomatosis of the endocrine pancreas in patients with and without the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30:560–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodei L, Sundin A, Kidd M, et al. The status of neuroendocrine tumor imaging: from darkness to light? Neuroendocrinology 2015; 101:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goncalves TD, Toledo RA, Sekiya T, et al. Penetrance of functioning and nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 in the second decade of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99:E89–E96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kann PH, Balakina E, Ivan D, et al. Natural course of small, asymptomatic neuroendocrine pancreatic tumours in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: an endoscopic ultrasound imaging study. Endocr Relat Cancer 2006; 13:1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akerstrom G, Stalberg P, Hellman P. Surgical management of pancreatico-duodenal tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012; 67 Suppl 1:173–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanazaki K, Sakurai A, Munekage M, et al. Surgery for a gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (GEPNET) in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surg Today 2013; 43:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Network NCC. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Neuroendocrine Tumors, Version 1. 2015. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/ Accessed February 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito T, Igarashi H, Jensen RT. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: clinical features, diagnosis and medical treatment: advances. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 26:737–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niina Y, Fujimori N, Nakamura T, et al. The current strategy for managing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Gut Liver 2012; 6:287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadot E, Reidy-Lagunes DL, Tang LH, et al. Observation versus resection for small asymptomatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a matched case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 23:1361–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sallinen V, Haglund C, Seppanen H. Outcomes of resected nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: do size and symptoms matter? Surgery 2015; 158:1556–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg AM, Friedmann P, Del Rivero J, et al. Resection versus expectant management of small incidentally discovered nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery 2015; 159:302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regenet N, Carrere N, Boulanger G, et al. Is the 2-cm size cutoff relevant for small nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a French multicenter study. Surgery 2016; 159:901–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoo YJ, Yang SJ, Hwang HK, et al. Overestimated oncologic significance of lymph node metastasis in G1 nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumor in the left side of the pancreas. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94:e1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toste PA, Kadera BE, Tatishchev SF, et al. Nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors <2 cm on preoperative imaging are associated with a low incidence of nodal metastasis and an excellent overall survival. J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 17:2105–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hausman MS, Jr, Thompson NW, Gauger PG, et al. The surgical management of MEN-1 pancreatoduodenal neuroendocrine disease. Surgery 2004; 136:1205–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gauger PG, Doherty GM, Broome JT, et al. Completion pancreatectomy and duodenectomy for recurrent MEN-1 pancreaticoduodenal endocrine neoplasms. Surgery 2009; 146:801–806. discussion 807–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davi MV, Boninsegna L, Dalle Carbonare L, et al. Presentation and outcome of pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. Neuroendocrinology 2011; 94:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nell S, Borel Rinkes IH, Verkooijen HM, et al. Early and late complications after surgery for MEN1-related nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg 2016; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbe C, Murat A, Dupas B, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus endoscopic ultrasonography for the detection of pancreatic tumours in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Dig Liver Dis 2012; 44:228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ito T, Jensen RT. Imaging in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: recent studies show enhanced sensitivities but increased controversies. Int J Endocr Oncol 2016; 3:53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marinoni I, Kurrer AS, Vassella E, et al. Loss of DAXX and ATRX are associated with chromosome instability and reduced survival of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastroenterology 2014; 146:453.e5–460.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]