Abstract

Memory stem T (TSCM) cells, a new subset of memory T cells with self-renewal and multipotent capacities, are considered as a promising candidates for adoptive cellular therapy. However, the low proportion of human TSCM cells in total CD8+ T cells limits their utility. Here, we aimed to induce human CD8+ TSCM cells by stimulating naive precursors with interleukin-21 (IL-21). We found that IL-21 promoted the generation of TSCM cells, described as CD45RA+CD45RO−CD62L+CCR7+CD122+CD95+ cells, with a higher efficiency than that observed with other common γ-chain cytokines. Upon adoptive transfer into an A375 melanoma mouse model, these lymphocytes mediated much stronger antitumor responses. Further mechanistic analysis revealed that IL-21 activated the Janus kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway by upregulating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 phosphorylation and consequently promoting the expression of T-bet and suppressor of cytokine signaling 1, but decreasing the expression of eomesodermin and GATA binding protein 3. Our findings provide novel insights into the generation of human CD8+ TSCM cells and reveal a novel potential clinical application of IL-21.

Key Words: memory stem T cell, adoptive transfer, interleukin-21, STAT3

Efforts towards understanding T-lymphocyte memory have revealed the extraordinary potential of adaptive immunity. In infection and cancer, T lymphocytes expand and differentiate into effector cells for clearing the pathogen and into memory cells, which can survive for a long time and ensure protection against pathogens upon antigen rechallenge. Human T lymphocytes are commonly subdivided into naive precursor (TN) cells, central memory (TCM) cells, effector memory (TEM) cells, and effector cells. The progressive differentiation of T lymphocytes leads to a gradual loss of functional and therapeutic potential. Recent work has revealed the existence of a newly reported T-cell subset, T memory stem (TSCM) cells, in a graft-versus-host disease mouse model1 and subsequently in human and nonhuman primates.2,3 This T-cell population is phenotypically defined as CD45RA+CD62L+, and is distinguishable from TN cells by the expression of the memory markers CD95 and CD122 in humans. Functionally, TSCM cells can rapidly differentiate into memory and effector cells upon encountering antigens, which proves that they share the abilities of multipotency and self-renewal with TN cells.2 Moreover, with higher antitumor activity and survival, TSCM cells have been proved to prolong lifespan in mouse tumor models and human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) patients.2,4 In light of these appealing characteristics, TSCM cells hold great promise for overcoming the current limitations of T-cell-based immunotherapies. However, the low proportion of TSCM cells in the peripheral blood limits their utility in immunotherapy.2 Although a potent Wnt-catenin signaling activator, TWS119,5 and the γ-chain cytokines IL-7 and IL-156 have been reported to be effective for TSCM-cell induction, for TSCM-based immunotherapies to be clinically practicable, large-scale and well-functional ex vivo TSCM expansion is required.

Interleukin-21 (IL-21), the youngest member in the common γ-chain cytokine family, is mainly produced by CD4+ T cells and has a pleiotropic effect on both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses by regulating B cell, dendritic cell, natural killer (NK) cell, and CD4+ T-cell function.7 The effects of IL-21 in the development of innate immunity and CD4 T helper cell responses are well characterized, but its role in the priming of the CD8+ T-cell response, particularly in humans, has not been fully explored. IL-21, similar to IL-2, enhances antigen activation and clonal expansion of CD8+ T cells. However, in contrast to IL-2, IL-21 does not induce the effector cells undergoing activation-induced cell death (AICD) after long-term exposure.8 In addition, IL-21 tends to retain CD8+ T cells in a state of higher developmental plasticity by inhibiting the antigen-induced expression of differentiation-related transcriptional factors (TFs) and by preventing exhaustion of CD8+ T cells.9 For CD8+ memory T cells, IL-21 maintains the expression of the costimulation receptor CD28 and functions as a key regulator to switch the proliferation between aged and fresh memory human CD8+ T cells.10,11 Moreover, IL-21 strongly synergizes with either IL-7 or IL-15 to improve the killing ability of CD8+ T cells by promoting cell proliferation and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production. These distinctive effects of IL-21 on CD8+ T cells make it an antitumor cytokine with therapeutic potential. Therefore, whether IL-21 can enhance the homeostasis of all types of functional memory CD8+ T cells merits further investigation.

In this study, we aimed to use IL-21 to induce human CD8+ TSCM cells from naive precursors in vitro and we found that IL-21 facilitated the generation of CD8+ TSCM cells from naive precursors with identical phenotypical and functional features. The IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells had increased cytotoxic capacity and mediated more efficient antitumor responses than CD8+ cells induced using other γ-chain cytokines. IL-21 also triggered signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation and correspondingly promoted the expression of T-box 21 (TBX21) and suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1). These findings provide a novel method for in vitro TSCM-cell expansion and indicate the potential of IL-21 in cytokine immunotherapy.

RESULTS

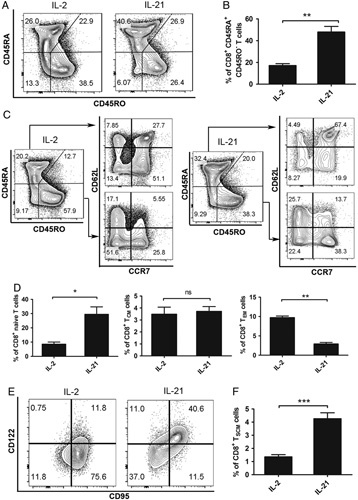

IL-21 Induced the Generation of a TSCM-cell Population From Naive Precursors

To evaluate the potential effect of IL-21 on CD8+ T lymphocytes, naive CD8+ T lymphocytes were sorted by flow cytometry to >98% purity and then activated with coated anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 antibodies, followed by stimulation with IL-2 or IL-21. A fraction of CD45RA+CD45RO− naive-like cells remained among the IL-21-stimulated CD8+ lymphocytes, which was consistent with that in CD8+ lymphocytes stimulated with IL-2 (Fig. 1A, B). Next, we performed phenotypic analysis of the homing markers CD62L and CCR7 on CD45RA single-positive and CD45RO single-positive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1C). The IL-21-stimulated naive CD8+ T cells maintained CD45RA expression, and in this CD45RA+CD45RO− subgroup, we observed a higher level of CD62L and CCR7 expression (Figs. 1C, D). Although IL-2 and IL-21 triggered similar proportions of CD45RA−CD45RO+ T cells and TCM (Fig. 1D),12 IL-2 enhanced the differentiation of CD62L−CCR7− cells, which are defined as TEM cells (Figs. 1C, D). In contrast, IL-21 was sufficient for maintaining the phenotypic expression characteristics of naive T cells.

FIGURE 1.

IL-21 induces the formation of a TSCM population from naive precursors. A, Flow cytometry analysis of sorted human CD45RO−CD62L+ naive CD8+ T cells after stimulated with coated anti-CD3, soluble anti-CD28 in the presence of IL-2 (10 ng/mL) or IL-21 (20 ng/mL) for 14 days. Data are gated on total CD8+ T cells. B, Percentages of CD45RA+CD45RO−CD8+ T cells in the CD8+ population as described in (A). C, Flow cytometry analysis of sorted human naive CD8+ T cells stimulated as described in (A). Data are gated on CD45RA or CD45RO single-positive CD8+ T cells as indicated. D, Frequency of 3 T-cell subsets gated in (C). Naive T cell, CD45RA+CD45RO−CD62L+CCR7+. TCM, CD45RA−CD45RO+CD62L+CCR7+. TEM, CD45RA−CD45RO+CD62L−CCR7−. E, Flow cytometry analysis of sorted human naive CD8+ T cells stimulated as described in (A). Data are gated on total CD8+ T cells. F, Frequency of the memory stem T cells gated in (E). TSCM, CD45RA+CD45RO−CD62L+CCR7+CD95+CD122+. Data were presented as means±SEM (error bars) of 6 (A, B), 8 (C, D), or 9 (E, F) healthy donors. The paired t test was used. P<0.05 indicates statistically significant difference. IL-21 indicates interleukin-21; ns, not significant; TCM, central memory cell; TEM, T effector memory cell; TSCM, T memory stem cell. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Human TSCM cells share similar expression of a vast majority of molecules as TN cells.2 Therefore, to clarify whether the cell group induced by IL-21 consisted of conventional naive T cells, the expression of 2 memory T-cell-associated surface markers, CD95, and CD122, was analyzed in the CD45RA+CD45RO− subgroup. The expression of these 2 markers with IL-21 stimulation was much higher than that observed with IL-2 stimulation (Figs. 1E, F). Together, these results indicate that in naive precursors, IL-21 was better at preserving the expression of both naive cell-related and memory cell-related surface markers and inducing the formation of a CD8+ TSCM-cell population, which is phenotypically defined here as CD45RA+CD45RO−CD62L+CCR7+CD95+CD122+ T cells and was identical with previously reported TSCM-cell populations.2

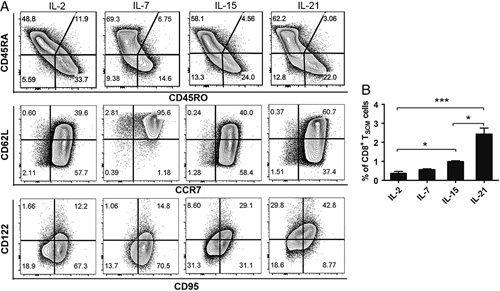

Among the Common γ-Chain Family Cytokines, IL-21 Showed the Best Potential to Induce the Differentiation of TSCM Cells In Vitro

Previous data show that the combination of IL-7 and IL-15 generates human TSCM cells from naive precursors.6 However, as all common γ-chain family cytokines can support T-cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation,13 we elucidated the potential and sensitivity of IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 in generating TSCM cells (Fig. 2A). IL-15 alone was effective to stimulate the differentiation of TSCM cells from CD8+ naive T cells as observed previously6; however, neither IL-2 nor IL-7 could sufficiently induce the formation of TSCM cells (Fig. 2B). Moreover, IL-21 showed the highest potential to induce TSCM-cell formation; the proportion of TSCM cells obtained with IL-21 stimulation was ~5-fold higher than that obtained with IL-2 stimulation and 2-fold higher than that obtained with IL-15 stimulation (Fig. 2B). IL-21 stimulation was found to maintain a growing number of total CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3A) and TSCM cells (Fig. 3B) over time. Furthermore, the number of TSCM cells obtained increased with an increase in IL-21 concentration (Figs. 3C, D). In addition, increasing concentration of IL-21 also leaded to increasing proportion of TSCM cells (Fig. 3E). The effect of IL-21 on CD8+ T-cell expansion was further verified using the carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) assay. The vast majority of isolated naive CD8+ T cells treated with IL-2 or IL-21 had undergone cell division beginning from day 3 (Fig. 3F). Given that IL-2 is commonly used as a signaling cytokine for T-cell proliferation in vitro, the data suggest that both IL-21 and IL-2 supported sustained CD8+ T-cell expansion. Taken together, these results indicate that, among the common γ-chain family cytokines, IL-21 provides a superior choice for differentiating and maintaining TSCM cells from CD8+ naive T lymphocytes and for arresting them in a dynamic balance state.

FIGURE 2.

IL-21 instructs the generation of CD8+ TSCMs better than other common γ-chain family cytokines. A, Flow cytometry analysis of sorted human naive CD8+ T cells after the 2-week stimulation with coated anti-CD3, soluble anti-CD28 in the presence of IL-2 (10 ng/mL), IL-7 (10 ng/mL), IL-15 (10 ng/mL), or IL-21 (20 ng/mL). Data are gated on total CD8+ T cells. B, Percentages of TSCM cells obtained as described in (A). Data were presented as mean±SEM (error bars) of 6 (A, B) healthy donors. The paired t test was used. P<0.05 indicates statistically significant difference. IL-2 indicates interleukin-2; TSCM, T memory stem cell. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

FIGURE 3.

IL-21 enhances proliferation and prevents apoptosis of activated naive CD8+ T cells. A, Cell counting of CD8+ T cells in day 0, 5, 10, and 15 with standard medical blood count board. B, Total CD8+ TSCM-cell numbers from day 0 to day 14. Cell number was calculated as the total CD8+ T-cell number multiplied by the percentage of CD8+ TSCM cells accessed by flow cytometric analysis in the indicated time points. C, The number of CD8+ T cells stimulated with gradient doses of IL-21. D, The percentage of CD8+ TSCM cells in the indicated dose of IL-21. E, Flow cytometric analysis of CD8+ TSCM cells in the indicated dose of IL-21. Graphs showed T cells after gating on CD8+ CD45RA+ CD45RO− CD62L+ CCR7+ cells. F, CFSE-labeled naive CD8+ T cells primed with 10 ng/mL IL-2 or 20 ng/mL IL-21. Flow cytometric analysis was performed 3 days or 7 days after activation. Data were analyzed with linear regression model. IL-21 indicates interleukin-21; TSCM, T memory stem cell.

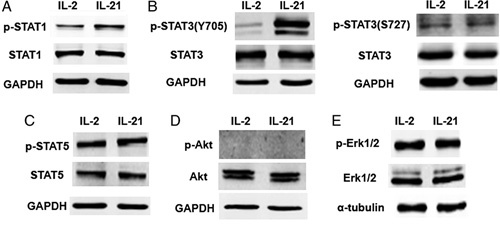

STAT3 is Involved in IL-21-Induced CD8+ TSCM-Cell Formation

IL-21 is involved in the Janus kinase STAT signaling pathway, where it mainly mediates CD8+ T-cell proliferation through STAT1 and STAT3.14 Here we explored the potential mechanism by which IL-21 enhances the induction and proliferation of TSCM cells using western blotting analysis for the phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 proteins. IL-21-induced strong STAT3 and weak STAT1 phosphorylation in comparison with that observed in the control CD8+ T cells, whereas IL-2 induced strong STAT1 phosphorylation and negligible STAT3 phosphorylation (Figs. 4A, B). It was notable that IL-21 virtually dephosphorylated STAT5 when compared with that observed in the control and IL-2-stimulated cells (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

IL-21 only highly upregulates the phosphorylation of STAT3 in the process of TSCM priming. Naive CD8+ T cells display identical STAT phosphorylation profiles in response to IL-2 or IL-21. FACS-purified CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were activated with coated anti-CD3(2 μg/mL) and soluble anti-CD28(1 μg/mL) overnight, then stimulated with 10 ng/mL IL-2 or 20 ng/mL IL-21. Two hours after stimulation, cells were lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer. Equivalent amounts of proteins were analyzed by Western blot for indicated phosphoproteins. Data in STAT1 (A) STAT3 (B) STAT5 (C) Akt (D) and Erk1/2 (E) are shown representative of 3 experiments. IL-21 indicates interleukin-21; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TSCM, T memory stem cell.

IL-21 signaling through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways may also be relevant in certain physiological or pathologic conditions.15 We therefore further explored the phosphorylation of Akt and MAPK proteins. Upon stimulation with IL-2 or IL-21, Akt showed negligible phosphorylation (Fig. 4D), whereas MAPK was strongly phosphorylated (Fig. 4E). These results indicate that phosphorylated STAT proteins, particularly phosphorylated STAT3 and its downstream factors, are involved in this process.

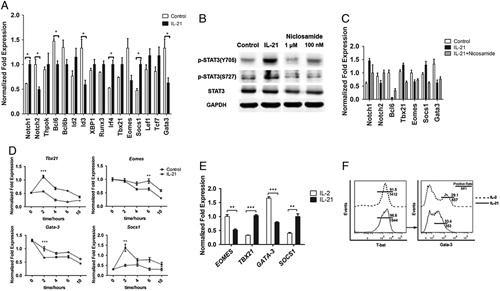

IL-21-Induced CD8+ TSCM Cells Showed Increased TBX21 and SOCS1 Expression and Reduced Eomesodermin (EOMES) and GATA Binding Protein 3 (GATA3) Expression

Several lines of evidence indicate that the IL-21 signaling pathway might regulate CD8+ T-cell differentiation. IL-21 induces SOCS1 expression through STAT3 and increases the numbers of TCM cells.16,17 T helper cell 1–related genes such as TBX21 and EOMES, which regulate the fate of CD8+ T-cell differentiation, can also be modified by IL-21.18 In addition, GATA3, a TF that controls the maintenance and proliferation of peripheral CD8+ T cells, is affected by IL-21 stimulation.19 Therefore, to explore the candidate transactional factors associated with IL-21-mediated CD8+ TSCM-cell differentiation, we screened the TFs related to memory CD8+ T-cell development (Fig. 5A). Notably, the expression of Notch1, TBX21, and SOCS1 in cells stimulated with IL-21 was nearly 2-fold higher than that in cells activated with only anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies (control). In contrast, the expression of EOMES and GATA3, genes linked to mature effector CD8 T cells, was reduced by 50% in the IL-21-primed cells (Fig. 5A). We also further confirmed that the TFs were regulated through the IL-21-STAT3 axis using the STAT3 phosphorylation inhibitor, niclosamide (Figs. 5B, C). Among the TFs induced by IL-21 (Fig. 5A), only 7 TFs, NOTCH1 and NOTCH2, BCL6, TBX21, SOCS1, EOMES, and GATA3, were inversely regulated upon inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5C). The expression of TBX21, SOCS1, EOMES, and GATA3, showed a time-dependent relationship with IL-21 treatment (Fig. 5D). To confirm the stimulated effect of IL-21, cells were activated with coated anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 antibodies overnight, followed by stimulation with IL-2 or IL-21 for 2 more hours. The expression of TBX21, SOCS1, EOMES, and GATA3, showed the similar trend of regulation with IL-21 treatment (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, 14 days after stimulation with IL-21, CD8+ T cells displayed slightly higher T-bet and much lower GATA3 protein levels than the IL-2-primed cells, which corresponded with the mRNA expression analysis (Fig. 5F). On the basis of these results, we propose that IL-21 up-regulates TBX21 and SOCS1 and suppresses EOMES and GATA3, thus inducing CD8+ TSCM-cell formation and maintaining cell plasticity.

FIGURE 5.

IL-21 promotes the expression of T-bet and SOCS1 but inhibits the expression of Gata3 and Eomes. A, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of TFs related to CD8+ T-cell development in activated naive CD8+ T cells treated with or without IL-21 (20 ng/mL). Data are represented as mean±SEM (error bars). B, Immunoblot analysis of STAT3 phosphorylation in anti-CD3/CD28-activated naive T cells cultured with or without IL-21 and various doses of niclosamide (STAT3 phosphorylation inhibitor) for 3 hours. C, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the TFs related to IL-21 in (A) in response to niclosamide (100 nM). D, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of Tbx21, Eomes, Gata3, and SOCS1 in activated naive CD8+ T cells treated with or without IL-21(20 ng/mL). Data are represented as mean±SEM (error bars). E. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of Tbx21, Eomes, Gata3, and SOCS1 in activated naive CD8+ T cells treated with IL-2 (10 ng/mL) or IL-21 (20 ng/mL) for 2 hours after activation. F, Intercellular TFs staining of activated naive CD8+ T cells from a representative healthy donor after treating with IL-2 (10 ng/mL) or IL-21(20 ng/mL). All data were representative of at least 2 independently performed experiments. The paired t test was used. P<0.05 indicates statistically significant difference. EOMES indicates eomesodermin; IL-21, interleukin-21; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; SOCS1, suppressor of cytokine signaling 1; TBX-21, T-box 21; TFs, transcriptional factors. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

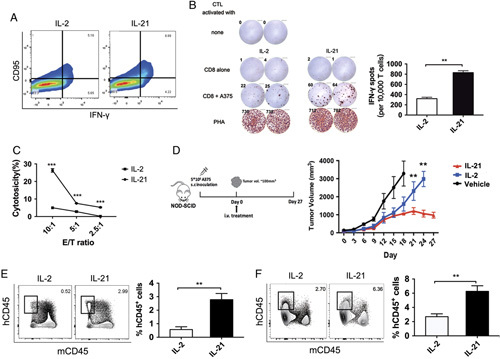

IL-21-Induced CD8+ TSCM Cells Induce Superior Antitumor Responses in a Humanized Melanoma Mouse Model

As a candidate for cancer immunotherapy, CD8+ TSCM cells exhibit remarkable antitumor and survival activity.2,5 Adoptive immunotherapy is considered to be one of the best methods to suppress immunogenic tumors such as melanoma.20,21 Therefore, in this study, to generate melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells, naive CD8+ T cells were stimulated in vitro with autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) pulsed with a cancer-testis antigen, NY-ESO-1. CD8+ T cells stimulated with IL-21 showed a high level of IFN-γ expression (Fig. 6A). Both IL-2-stimulated and IL-21-stimulated CD8+ T cells could be stimulated by PHA, confirming their capacity to respond to the antigen. Coincubation of IL-21-induced T cells with the NY-ESO-1 expressing tumor cell line MelA375 induced 3-fold higher IFN-γ secretion as determined by the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells showed stronger cytotoxicity against A375 cells, whereas little cytotoxicity was observed in the control group (Fig. 6C). We next evaluated the ability of IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells to induce regression of an established human A375-derived melanoma in vivo. When the tumors reached a size of ~100–150 mm3, the IL-2-induced or IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells were intravenously injected into the mice randomly allocated to the indicated groups. Tumor size was measured using calipers every 3 days, and tumor volume was estimated. Tumors grew consistently from day 9 in mice receiving IL-2-induced CD8+ T cells. By contrast, mice receiving IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells experienced a rapid cessation of tumor growth within 10 days of injection. Over the study period, adoptive transfer of autologous IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells effectively inhibited the growth of A375 tumor xenografts in the mice (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, we tracked the adoptive human T cells in vivo. Flow cytometry analysis of human T cells in spleen and explanted tumors was performed at day 7 post transfers or at the endpoint of the experiments. Single-cell suspensions were stained with anti-human CD45 and anti-mouse CD45 antibodies. IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells showed enhanced survival capacity, as revealed by the frequencies of human T cells in the spleens of mice after transfer (Fig. 6E). Notably, IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells showed a strong increase of T-cell infiltration into tumors (Fig. 6F). Together, these data indicate that IL-21 is capable of generating more potent tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, which depended on its potential to stimulate TSCM-cell differentiation.

FIGURE 6.

IL-21-induced CD8+ TSCM cells mediate superior antitumor responses in a melanoma xenograft model. A, Flow cytometry analysis of IFN-γ expression in sorted human naive CD8+ T cells after the 2-week stimulation with coated anti-CD3, soluble anti-CD28 in the presence of IL-2 (10 ng/mL), or IL-21 (20 ng/mL). Data are gated on total CD8+ TSCM cells. B, IFN-γ release by IL-21-induced CD8+ T cells compared with IL-2-induced CD8+ T cells (control) in response to NY-ESO-1-expressing A375 melanoma cell lines. The IFN-γ production was measured by ELISPOT assay. Data were representative of 2 independently performed experiments. The paired t test was used. **P<0.01. C, The educated CD8+ T cells were mixed with melanoma cell line A375 in a 12-hour cytotoxicity assay at E/T ratios from 10 to 2.5. The cell lysis rate was measured with the LDH release assay. Three replicates were used for each dilution of effector cells. Data are presented as means±SEM (error bars) (n=3; 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for statistical analysis of the data; ***P<0.001). D, Mice bearing human A375 tumor xenografts received adoptive therapy of IL-2-stimulated or IL-21-stimulated CD8+ T cells as indicated. Tumor growth was measured by caliper twice per week. Data are 1 representative of 3 independent experiments (4–6 mice in each experiment). **P<0.01 after 20 days. Mann-Whitney U test was used. E, Flow cytometry analysis for human CD45+ and mouse CD45+ cells 7 days after the adoptive transfer of indicated T cell. Percentages of human T cells are shown. Data are from 3 to 5 mice per group. The paired t test was used. P<0.05 indicates statistically significant difference. **P<0.01. F, Flow cytometry analysis of human T cells in tumor xenografts at study endpoint. Percentages of human T cells are shown. Data are from 3 to 5 mice per group. The paired t test was used. P<0.05 indicates statistically significant difference. **P<0.01. ELISPOT indicates enzyme-linked immunospot; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-21, interleukin-21; TSCM, T memory stem cell.

DISCUSSION

Memory stem T cells, a new T-cell subset featured by the ability of long-term self-renewal and multipotency, have wide-ranging clinical implications. Adoptive transfer of TSCM cells has shown promising antitumor activity and is more therapeutically effective than the adoptive transfer of conventional TCM and TEM cells.2 In the present study, we found that IL-21 could effectively facilitate the generation of CD8+ TSCM cells from naive precursors. These IL-21-induced CD8+ TSCM cells, compared with CD8+ cells induced using other γ-chain cytokines, had greater cytotoxic capacity and could mediate more efficient antitumor responses in vivo.

Using TSCM cells in adoptive immunotherapy against cancer may overcome the limitations of current therapy methods using other memory T cells, that is, limited lifespan of T-cell engraftment, insufficient therapeutic ability, and short-term immune attack. Therefore, TSCM cells are considered a promising candidate for adoptive immunotherapy. Recently, TSCM cells have also been found to preserve their precursor potential in humans after HSCT, which highlights their potential for diversification of immunologic memory after allogeneic HSCT.4,22 After vaccination or pathogenic challenge, CD8+ TSCM cells are efficiently induced and persist for decades, and they retain a naive T-cell-like profile and memorize specific antigens.23,24 In the present study, we showed that TSCM cells, induced in vitro with IL-21, mediated profound immune responses against tumor antigens. These IL-21-induced CD8+ TSCM cells exhibited high levels of IFN-γ secretion and strong cytotoxicity in vitro upon encountered tumor antigens. Moreover, when transferred into human melanoma-bearing mice, these cells showed profound antitumor activity in vivo. Therefore, our data support the therapeutic potential of the application of TSCM cell in adoptive immunotherapy against cancer.

However, the low proportion of human TSCM cells, accounting only for ~2%–3% of the total CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood, limits their utility in immunotherapy.2,25 Current methods to generate TSCM cells in vitro mainly depend on small compounds, such as TWS119 and rapamycin, the inhibitor of GSK-3β and mTOR signaling, respectively.5,26 However, these compounds are negative regulators of T-cell differentiation and are toxic to CD8+ T cells. In recent years, γ-chain family cytokines have been found capable of generating CD8+ TSCM cells,6 which enables human TSCM-based immunotherapy in a safer way. Combinations of these cytokines, sometimes supplemented with the small molecular inhibitors mentioned previously, have shown great potential for the generation of CD8+ TSCM cells. For example, a recent study showed that IL-7, IL-21, and TWS119 collaboratively induced naive T cells to become cells highly resembled natural TSCM cells.27 IL-21 was also found to augment rapamycin in the induction of CD8+ TSCM cells.28 In addition, it has been reported that compared with prolonged activation, a short-term anti-CD3/CD28 costimulation of naive T cells, combined with IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21, significantly increased the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ TSCM cells.29 In this study, starting from naive precursors, we showed that human TSCM cells can be expanded and sustained using IL-21 alone. IL-21 could not only induce, but also help to preserve the critical stem cell-like features of TSCM cells, more effectively than IL-7 or IL-15. These findings highlight the role of IL-21 in in vitro expansion of TSCM cells. In addition to CD8+ TSCM cells, it is also noteworthy that IL-21 has also been suggested to play a role in the induction and expansion of cytotoxic CD8+ T effector cells, NK cells, and NKT cells, as well as in the suppression of Treg expansion via the inhibition of FOXP3.7,30–34 On the basis of these studies, the antitumor activity of IL-21 has been applied in multiple preclinical studies, where IL-21 was used as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy,35–38 and its applicability has been evaluated in clinical trials for renal cell carcinoma and metastatic melanoma.39–42 Therefore, our results suggest the important role of IL-21 in the future therapeutic application of TSCM cells and provide additional evidence of the clinical potential of IL-21 in antitumor therapies.

The transcriptional control of CD8+ TSCM-cell differentiation is still unclear. In our present study, we also identified the potentially important regulators in the CD8+ TSCM-cell differentiation, such as TFs STAT3, TBX21, EOMES, SOCS1, and Notch1. Especially, TBX21 and EOMES collaboratively played a critical role in deciding the fate of CD8+ T cells43 by inducing the expression of CD122 and mediating the cooperation of IL-15-specific responsiveness and the spectrum of effector functions.18 Furthermore, neither TBX21 nor EOMES deficiency causes a severe reduction in the number of effector or TCM cells; rather it increases the percentage of CD62Lhigh CD44low Sca-1+ T cells, which are phenotypically similar to TSCM cells. In a short culture experiment in vitro, we assumed that the upregulation of TBX21 might suppress the expression of EOMES and then function in TSCM formation. Similarly, SOCS1 also plays a critical role in CD8+ T cell development. High SOCS1 expression enhances the differentiation of thymocytes toward CD8+ T cells and results in very high proportions of peripheral CD8+ T cells with a memory phenotype.44 In the absence of SOCS1, IL-21 significantly potentiates IL-7-induced and IL-15-induced proliferation of CD8+ T cells displaying a partial memory phenotype.17,45 However, activation of STAT through phosphorylation triggers the expression of SOCS1, which in turn acts as a negative modulator for STAT3.16 Therefore, based on these recent findings of the field, our results support that the balance between STAT and SOCS proteins plays a significant role in inducing TSCM formation and arresting effector T-cell differentiation during IL-21 stimulation.

In summary, our results highlight the clinical potential of IL-21 in promoting the generation of TSCM cells for antitumor adoptive immunotherapy. We also identified the potentially important regulators in the CD8+ TSCM-cell differentiation, such as TFs GATA3 and TBX21. On the basis of these findings, future studies should provide further insights into the mechanism of the TSCM generation, and explore the clinical potential of IL-21 in immunotherapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Sun Yat-Sen University. Healthy donors comprised of a group of local volunteers, who were seronegative and had no reported history of chronic illness or IV drug use. All mouse experiments were approved by the Sun Yat-Sen University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The NOD/Shi-scid, IL-2RγKO (NOG) female mice were purchased from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Japan). All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with ethical guidelines for animal care of Sun Yat-sen University. Animals of 8–12 weeks of age were used for experiments.

Purification of Human Naive CD8+ T Lymphocytes

Human PBMCs were isolated from the whole blood of healthy donors with Ficoll-Hypaque Solution (Hao Yang, China); human CD8+ T lymphocytes were then purified with human CD8+ T-cell isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD IMag). Cells were then labeled with anti-CD8 (clone RPA-T8; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), anti-CD45RO (clone UCHL1; BD Pharmingen), and anti-CD62L (clone DREG56; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) fluorescent antibodies and Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-purified into naive CD8+ T cells on a FACSAria cell sorter (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Postsorting analysis of purified subsets revealed >98% purity.

In vitro Culture and Differentiation

Sorted naive CD8+ T lymphocytes were cultured in the completed RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 units/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1×MEM with nonessential amino acids and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. The CD8+ naive T cells were activated by 2 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3 antibody (R&D system, Minneapolis, MN) and 1 μg/mL soluble anti-CD28 antibody (R&D) and then cultured with recombinant human (rh) IL-2, rhIL-7, rhIL-15, or rhIL-21 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) in the indicated concentrations. Medium fed with cytokines was replaced every 3–4 days. Cells were counted every 3–4 days.

Flow Cytometric Analyses

Cells were labeled with fluorescent antibodies against the following targets: CD8, CCR7 (clone 150503), CD95 (clone DX2), CD122 (clone Mik-β2), T-BET (clone O4-46), GATA3 (clone L50-823), IFN-γ, CD45RO (clone 4S.B3, all from BD Pharmingen), CD62L, and CD45RA (clone 2H4; Beckman coulter, Miami, FL).

Single-cell suspensions were prepared. The cell surface was stained for 30 minutes at 4°C with anti-CD8, anti-CCR7, anti-CD95, anti-CD122, anti-CD45RO, anti-CD62L, or anti-CD45RA.

For intracellular cytotoxic cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL staphylococcal enterotoxin B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 100 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 μg/mL anti-human CD28 (R&D) for 6 hours, followed by addition of brefeldin A (5 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) at 2 hours before detection. Cells were washed twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm and Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD Cytoperm). Stained samples were analyzed in a BD LSR II Fortessa and flow cytometric data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

CFSE Staining

Every 1×106 CD8+ naive T cells were incubated with 100 μL of PBS and 1 μM CFSE (Life Technologies Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD) at 37°C. After 15 minutes, the reaction was terminated by addition of RPMI 1640 medium. Cells were centrifuged, followed by rinsing twice with PBS. Cell divisions were measured by FACS analysis at days 3 and 7.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

The total RNAs were isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA was generated by reverse transcription with PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed with SYBR Premix ExTaq II Kit (Takara) by using the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). The instructions of the manufacturer were followed. The relative level of gene expression was calculated in comparison with the housekeeping gene encoding b-actin (Actb) or GAPDH (GAPDH).

Western Blotting

The collected cells were lysed in M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with a cocktail of protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Coomassie Blue staining was performed for protein quantitation. Total protein (20 μg) was separated on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel followed by standard immunoblotting with primary antibodies for Stat1, phospho-Stat1 (Tyr701), Stat3, phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705, Ser727), Stat5, phospho-Stat5 (Tyr694), Akt, phospho-Akt (Ser473), Erk1/2, phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and GAPDH (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) or α-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by fluorescence-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR, Lincoln).

Antigen-specific Expansion of Adoptive T Cells

The sorted naive CD8+ T lymphocytes were initially cultured with irradiated (60 Gy) PBMCs loaded with NY-ESO-1157-165 peptide (5 mmol/mL) at a ratio of 1: 10 in the presence of indicated IL-2 or IL-21. After 9 days in culture, the NY-ESO-1-stimulated T cells were restimulated with 2 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3 antibody and 1 μg/mL soluble anti-CD28 antibody, and continually cultured in the presence of IL-2 or IL-21 for another 14 days. The collected cells were tested for antitumor activity toward melanoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo.46

ELISPOT Assays

ELISPOT assays were performed with a commercially available human IFN-γ precoated ELISPOT kit (DAKEWE). The manufacturer’s protocol was followed with minor modifications. Briefly, the indicated CD8+ T cells (7.5×104 cells/well) were incubated with target cells (1×104 cells/well) on precoated PVDF plates for 18 hours. To visualize spots, streptavidin-HRP and substrate were added. Spots were enumerated using a CTL Immunospot S5 core analyzer, and the data were analyzed using CTL ImmunoSpot software (Cellular Technology).

CTL Cytotoxicity Assays

CTL cytotoxicity assays against human melanoma A375 cells were performed using an LDH release assay (CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay; Promega). The experiments were performed in 96-well round-bottom plates according to the manufacturer’s protocol. T cells were educated as described previously. The target cells were plated in 96-well round-bottom plates at 1×104 cells/well. The indicated CD8+ T cells were then added at an E:T ratio of 10:1, 5:1 or 2.5:1. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 12 hours. Cytotoxicity was calculated by using the following formula:

|

Mouse Xenograft Models

For the tumor growth inhibition studies, acclimatized immunodeficient NOG mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 5×106 A375 melanoma tumor cells on the right flank. Tumors were measured 3 times per week with calipers in 2 perpendicular dimensions, and tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula: volume (mm3)=(length×width2)/2. When tumors achieved ~100–150 mm3, the mice were divided randomly into 3 groups, receiving injections of 5×106 IL-2-stimulated or IL-21-stimulated T cells, or PBS as a control. Autologous CD8+ T cells were educated by NY-ESO-1 pulsed PBMCs. Mice were sacrificed when the tumor volume reached 3000 mm3.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed with Graphpad Prism 5 (Graphpad Software). Data are shown as the mean±SEM, unless otherwise indicated. One-tailed paired t test was used for comparison between matched paired groups. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was used for comparison of 3 or more groups in a single condition. Correlation was estimated by calculation of 2-tailed Pearson coefficients and significance.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This work was supported by the Introduction of Innovative R&D Team Program of Guangdong Province (2009010058), the International Collaboration Program of Natural Science Foundation of China and US NIH (81561128007), the Important Key Program of Natural Science Foundation of China (81590765), the National Special Research Program for Important Infectious Diseases (2013ZX10001004), the Joint-innovation Program in Healthcare for Special Scientific Research Projects of Guangzhou (201508020256), Industry-Academia-Research planning project of Guangdong (2014B090904065) to H.Z. This work was supported by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2016M600700) to Y.Z. All authors have declared there are no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this work

Footnotes

Y.C. and F.Y. contributed equally.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang Y, Joe G, Hexner E, et al. Host-reactive CD8+ memory stem cells in graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:1299–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med. 2011;17:1290–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lugli E, Dominguez MH, Gattinoni L, et al. Superior T memory stem cell persistence supports long-lived T cell memory. J Clin Invest. 2013;123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira G, Ruggiero E, Stanghellini MTL, et al. Tracking genetically engineered lymphocytes long-term reveals the dynamics of T cell immunological memory. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:317ra198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:808–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cieri N, Camisa B, Cocchiarella F, et al. IL-7 and IL-15 instruct the generation of human memory stem T cells from naive precursors. Blood. 2013;121:573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parrish-Novak J, Dillon SR, Nelson A, et al. Interleukin 21 and its receptor are involved in NK cell expansion and regulation of lymphocyte function. Nature. 2000;408:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moroz A, Eppolito C, Li Q, et al. IL-21 enhances and sustains CD8+ T cell responses to achieve durable tumor immunity: comparative evaluation of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21. J Immunol. 2004;173:900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinrichs CS, Spolski R, Paulos Cm, et al. IL-2 and IL-21 confer opposing differentiation programs to CD8+ T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;111:5326–5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Bleakley M, Yee C. IL-21 influences the frequency, phenotype, and affinity of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response. J Immunol. 2005;175:2261–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen H, Weng N-p. IL-21 preferentially enhances IL-15-mediated homeostatic proliferation of human CD28+ CD8 memory T cells throughout the adult age span. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Förster R, et al. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by γc family cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:480–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng R, Spolski R, Casas E, et al. The molecular basis of IL-21–mediated proliferation. Blood. 2007;109:4135–4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-21: a double-edged sword with therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:379–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubo M, Hanada T, Yoshimura A. Suppressors of cytokine signaling and immunity. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagnon J, Ramanathan S, Leblanc C, et al. Regulation of IL-21 signaling by suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS1) in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Cell Signal. 2007;19:806–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Misumi I, Gu AD, et al. GATA-3 controls the maintenance and proliferation of T cells downstream of TCR and cytokine signaling. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:714–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer: a clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:16168–16173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cieri N, Oliveira G, Greco R, et al. Generation of human memory stem T cells after haploidentical T-replete hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2015;125:2865–2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stemberger C, Graef P, Odendahl M, et al. Lowest numbers of primary CD8+ T cells can reconstitute protective immunity upon adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2014;124:628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marraco SAF, Soneson C, Cagnon L, et al. Long-lasting stem cell-like memory CD8+ T cells with a naïve-like profile upon yellow fever vaccination. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:282ra248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lugli E, Gattinoni L, Roberto A, et al. Identification, isolation and in vitro expansion of human and nonhuman primate T stem cell memory cells. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scholz G, Jandus C, Zhang L, et al. Modulation of mTOR signalling triggers the formation of stem cell-like memory T cells. EBioMedicine. 2016;4:50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabatino M, Hu J, Sommariva M, et al. Generation of clinical-grade CD19-specific CAR-modified CD8+ memory stem cells for the treatment of human B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2016;128:519–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeza VT, Li X, Chen J, et al. IL-21 augments rapamycin in expansion of alpha fetoprotein antigen specific stem-cell-like memory t cells in vitro. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarez-Fernandez C, Escriba-Garcia L, Vidal S, et al. A short CD3/CD28 costimulation combined with IL-21 enhance the generation of human memory stem T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. J Transl Med. 2016;14:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutherland AP, Joller N, Michaud M, et al. IL-21 promotes CD8+ CTL activity via the transcription factor T-bet. J Immunol. 2013;190:3977–3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasaian MT, Whitters MJ, Carter LL, et al. IL-21 limits NK cell responses and promotes antigen-specific T cell activation: a mediator of the transition from innate to adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2002;16:559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coquet JM, Kyparissoudis K, Pellicci DG, et al. IL-21 is produced by NKT cells and modulates NKT cell activation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 2007;178:2827–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, et al. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory TH17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jahrsdörfer B, Blackwell SE, Wooldridge JE, et al. B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells and other B cells can produce granzyme B and gain cytotoxic potential after interleukin-21-based activation. Blood. 2006;108:2712–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skak K, Kragh M, Hausman D, et al. Interleukin 21: combination strategies for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Disc. 2008;7:231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gelebart P, Zak Z, Anand M, et al. Interleukin-21 effectively induces apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma through a STAT1-dependent mechanism. Leukemia. 2009;23:1836–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatt S, Matthews J, Parvin S, et al. Direct and immune-mediated cytotoxicity of interleukin-21 contributes to antitumor effects in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;126:1555–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis ID, Skrumsager BK, Cebon J, et al. An open-label, two-arm, phase I trial of recombinant human interleukin-21 in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3630–3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson JA, Curti BD, Redman BG, et al. Phase I study of recombinant interleukin-21 in patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2034–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis ID, Brady B, Kefford RF, et al. Clinical and biological efficacy of recombinant human interleukin-21 in patients with stage IV malignant melanoma without prior treatment: a phase IIa trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2123–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrella TM, Tozer R, Belanger K, et al. Interleukin-21 has activity in patients with metastatic melanoma: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3396–3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kallies A. Distinct regulation of effector and memory T-cell differentiation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chong MM, Cornish AL, Darwiche R, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 is a critical regulator of interleukin-7-dependent CD8+ T cell differentiation. Immunity. 2003;18:475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer DC, Restifo NP. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) in T cell differentiation, maturation, and function. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:592–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yiwen Z, Shilin G, Yingshi C, et al. Efficient generation of antigen-specific CTLs by the BAFF-activated human B-lymphocytes as APCs: a novel approach for immunotherapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:77732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]