Abstract

What strategies help ethnic minority adolescents to cope with racism? The present study addressed this question by testing the role of ethnic identity, social support, and anger expression and suppression as moderators of the discrimination—adjustment link among 269 Mexican-origin adolescents (Mage = 14.1 years), 12 – 17 years old from the Midwestern U.S. Results from multilevel moderation analyses indicated that ethnic identity, social support, and anger suppression, respectively, significantly attenuated the relations between discrimination and adjustment problems, whereas outward anger expression exacerbated these relations. Moderation effects differed according to the level of analysis. By identifying effective coping strategies in the discrimination-adjustment link at specific levels of analysis, the present findings can guide future intervention efforts for Latino youths.

Keywords: Racial-ethnic discrimination, Mexican-origin adolescents, externalizing and internalizing problems, ethnic identity, social support, anger regulation

Racism is a reality that unfortunately continues to pose threats to well-being for racial-ethnic minority populations in the U.S (Lewis, Cogburn, & Williams, 2015). Consequently, it is important to identify effective coping strategies for those individuals dealing with racial-ethnic discrimination. Although the association between racism and mental health has been investigated in adults, Latino youths have received much less research attention; for example, in one literature review on the impact of racism on the health of children of color, only 3 out of 40 studies focused exclusively on Latinos (Pachter & García Coll, 2009). Currently, there are 17.9 million Latino children under the age of 18 (U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, 2015), representing the largest minority group of youths in the U.S. Moreover, Latino adolescents have reported higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms compared to other racial-ethnic groups (McLaughlin, Hilt, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007).

One significant contributing factor to such mental health disparities is exposure to racial-ethnic discrimination, an acute or chronic stressor, which has been consistently linked with poor mental health outcomes in racial-ethnic minority populations (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Racism refers to “beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that tend to denigrate individuals or groups because of phenotypic characteristics or ethnic group affiliation” (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999). Racial-ethnic discrimination has been defined as unfair treatment due to an individual’s race or ethnicity (Contrada et al., 2000). Prior research has indicated the detrimental impact of racial-ethnic discrimination on the adjustment of Latino youths, in terms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Berkel et al., 2010; Cano et al., 2015). Before advances can be made to help prevent these kinds of adjustment problems, it is critical to identify sources of risk or resilience that can potentially moderate the discrimination–mental health link. Yet, many questions remain unanswered regarding effective individual-level coping strategies that can reduce the detrimental impact of discrimination on adjustment, particularly in specific cultural contexts. The present study sought to fill this gap in the disparities literature using a stress and coping framework that specifically addresses how individuals cope with racism (Brondolo, ver Halen, Pencille, Beatty, & Contrada, 2009). A stress and coping approach is ideally suited to address this gap in the health disparities literature because racism and discrimination are considered complex stressors that have consequences for both mental and physical health (e.g., Williams & Mohammed, 2009); moreover, the identification of potential buffers of the effects of discrimination can inform practical interventions to help Latino adolescents cope effectively with such stressors. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that due to the structural nature of racism, the ultimate solution to the problem lies not at the individual level, but at the policy and systems levels. Thus, while it is critical to better understand how to support youth experiencing discrimination, there is also important macro-level work needed to interrupt intergenerational cycles of social disadvantage that perpetuate the existence of racism (e.g., Lewis et al., 2015).

The goal of the present study was to identify malleable risk and protective factors that moderate the discrimination–adjustment association among Mexican-origin adolescents. Three coping resources were the focus of the present investigation: ethnic identity, social support from family, friends, and significant others, and anger regulation. Given the importance of identity negotiation (e.g., Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), strong social bonds (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995; M. Wang & Eccles, 2012), and the acquisition of increasingly complex emotion regulation skills during the adolescent years (Crone & Dahl, 2012), these three coping resources—ethnic identity, social support, and anger regulation—are very salient during this developmental stage.

An Integrative Conceptual Framework

The present study was informed by an integrative conceptual model (Brondolo et al., 2009) focused on coping with racism which posits that racial-ethnic discrimination is a complex stressor that adversely influences mental health; coping processes may either assist individuals in offsetting the detrimental effect of discrimination on mental health or further degrade their adjustment. This model identifies three key coping strategies that can potentially attenuate the link between racism and adjustment: ethnic identity, social support, and anger coping (Brondolo et al., 2009). For the purpose of the present study, ethnic identity refers to ethnic identity affirmation/belonging/commitment (also referred to as “commitment” for brevity) and exploration (for an excellent conceptual overview of ethnic and racial identity, see Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014); social support refers to perceived adequacy of social support from family members, friends, and significant others; and, anger coping refers to two forms of anger regulation, namely outward anger expression and anger suppression. Specifically, this model predicts that a strong ethnic identity buffers an individual from the adverse effects of discrimination on their well-being. Similarly, social support is also predicted to offset the negative impact of discrimination on an individual’s adjustment. Finally, anger expression as a form of confrontation is predicted to help buffer the individual from the negative effect of discrimination on adjustment, whereas anger suppression is predicted to exacerbate the detrimental effect of discrimination on adjustment. One key strength of this integrative model is that it brings together coping strategies from disparate literatures, ranging from those focused on interindividual schemas (e.g., identity) and interpersonal relations (e.g., social support) to intrapersonal mechanisms, such as emotion regulation (e.g., anger suppression). Theoretically, these coping strategies (apart from anger suppression) are assumed to serve a stress-buffering role. However, empirical studies have yielded equivocal results regarding the impact of ethnic identity, social support, and anger regulation as coping strategies in the discrimination—health link among minority populations (Brondolo et al., 2009; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Therefore, we review some of these research findings next, highlighting the rationale for why each hypothesized coping strategy could serve to either buffer or exacerbate the deleterious effect of discrimination on adjustment.

Coping Strategies that Influence the Discrimination—Mental Health Link

A strong ethnic-racial identity may operate as a buffer against the negative impact of discrimination on adjustment because individuals with a strong sense of affirmation, belongingness, and commitment related to their racial-ethnic group are presumed to have psychological resources to draw upon in the face of assaults on their ethnic-racial identity via meaning-making, cognitive appraisal or coping (Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012; Umaña-Taylor, 2016). In other words, they will feel good about their ethnic-racial group membership despite unfair treatment based on their race or ethnicity (Rivas-Drake, Syed et al., 2014). For example, some research among Latino adolescents and adults shows that a strong ethnic identity buffers against the negative impact of discrimination on mental health (Torres, Yznaga, & Moore, 2011; Umaña-Taylor, Wong, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2012; Umaña-Taylor, Tynes, Toomey, Williams, & Mitchell, 2015). On the other hand, some research on Latino adolescents and adults shows that a strong ethnic identity may exacerbate the negative impact of discrimination on adjustment because individuals who are exploring their identity (e.g., Cheng, Hitter, Adams, & Williams, 2016; Torres & Ong, 2010; Torres et al., 2011) or those with a strong commitment to their ethnic group (e.g., Molina, Jackson, & Rivera-Olmedo, 2016; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2015) may be more sensitive to mistreatment or attacks based on their ethnic group membership.

Similarly, studies of social support have also yielded mixed results on whether or not they serve to buffer individuals against the negative impact of discrimination on their mental health (cf. Brondolo et al., 2009). On the one hand, social support may help to buffer individuals from the adverse effect of racial-ethnic discrimination because a supportive social network can offer individuals a sense of connection, security, and hope in receiving validation from others who may have shared in similar discrimination experiences. For example, recent studies have demonstrated that social support from family members, teachers, and peers mitigated the adverse effect of discrimination on Latino youths’ depressive symptoms and anxiety (Gonzalez, Stein, Kiang, & Cupito, 2014; Potochnick & Perreira, 2010). Alternatively, however, some research on social support among Latino adults has yielded null findings (Ai, Aisenberg, Weiss, & Salazar, 2014). It may be that the (perceived or received) social support does not offer the anticipated relief for the individual who has experienced discrimination, minimizes or denies the individual’s experience, or evokes greater anxiety in recollecting the experience of discrimination. It has also been suggested that social support may be more effective as a coping strategy for individuals exposed to low levels of a stressor such as discrimination, but that social support is insufficient to surmount the challenges posed by high levels of discrimination (Brondolo et al., 2009).

To our knowledge, there is no prior research explicitly testing the use of outward anger expression or anger suppression as coping strategies (i.e., moderators) in the discrimination—adjustment link among Latino youths. Whereas the literatures on identity and social support are relatively well-established as possible moderators in the discrimination—adjustment link, the area of anger regulation is relatively understudied as a potential moderator that can buffer (or exacerbate) the negative psychological impact of racial or ethnic discrimination. Outward anger expression (as a form of confrontation coping) could buffer individuals from the adverse effect of discrimination on their adjustment by allowing the individual to vent the negative emotions evoked by the discriminatory experience, prompting the perpetrator to change their discriminatory behavior or rousing others to action (Brondolo et al., 2009). For example, in a study examining discrimination among Latino college students (Dover, Major, Kunstman, & Sawyer, 2015), results indicated that anger can be a physiologically adaptive response to discrimination in terms of cardiovascular functioning. On the other hand, anger expression could also exacerbate the discrimination—adjustment link if the anger expression does not lead to resolution of the discrimination encounter or worse, if it leads to even greater interpersonal conflict or physical or intrapsychic harm. For instance, emerging research testing longitudinal mediational models has found that discrimination is associated with greater anger expression, which in turn is associated with poor mental and behavioral health outcomes among Latino (Park, Wang, Williams, & Alegría, 2017) and African American adolescents (Gibbons et al., 2010; Gibbons et al., 2012); these types of findings would suggest that anger expression as a coping strategy may be more likely to increase the detrimental impact of discrimination on adolescent adjustment.

Finally, very little (if any) research has addressed the role of anger suppression as a coping strategy in the link between racial-ethnic discrimination and adjustment among Latino adolescents. The limited empirical evidence suggests that anger suppression could exacerbate the discrimination—adjustment link in minority populations. For instance, Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2009) found that African American college students employed emotion suppression as an emotion regulation strategy in response to stigma-related stress, including discrimination, and greater emotion suppression predicted greater psychological distress. Anger suppression has also generally been associated with higher levels of psychopathology (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). Other research has found mixed or complex findings regarding the role of anger suppression and cardiovascular reactivity among African Americans (e.g., Dorr, Brosschot, Sollers, & Thayer, 2007; Steffen, 2003). Thus, it is not entirely clear whether and how anger expression and anger suppression, respectively, would influence the association between discrimination and adjustment for Latino youths. As a result, in the present study, anger expression and suppression were both tested in an exploratory manner without forwarding a specific hypothesis.

The Current Study

Theoretically and methodologically, the present study features three noteworthy innovative elements. First, given the mixed findings highlighted in our literature review, we pitted competing hypotheses against one another to see whether and how ethnic identity, social support, and anger regulation would serve as risk or protective factors in the link between perceived racial-ethnic discrimination and adjustment in the present sample of Mexican-origin adolescents. Thus, regardless of the results, the current study was expected to yield useful insights for the field with regard to how these theoretically-based coping strategies would operate among Latino adolescents. Second, the present study afforded the opportunity to capitalize on a longitudinal design which permitted an examination of how the hypothesized moderating roles of ethnic identity, social support, and anger regulation in the discrimination-adjustment link unfold across time within and between individuals. With these longitudinal data, we were able to decompose and evaluate three kinds of multilevel moderation effects (explained in more detail in the Data Analytic Strategy section) to gain a clearer understanding of within-person, between-person, and cross-level moderation effects. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that this approach (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006; Preacher, Zhang, & Zyphur, 2016; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) for decomposing multilevel moderation effects has been applied in the discrimination—health literature. Finally, the current study represents the first empirical test (E. Brondolo, personal communication, June 6, 2016) of a coping with racism model (Brondolo et al., 2009; described earlier in the Introduction) that combines knowledge from the diverse fields of identity development, social support, and emotion regulation, specifically among a sample of Mexican-origin adolescents. Thus, we investigated the following hypotheses, using a multilevel moderation approach: 1) ethnic identity will attenuate the discrimination—adjustment link; 2) social support will attenuate this link; and, 3) in an exploratory manner, outward anger expression and anger suppression, respectively, were both tested as moderators in the discrimination—adjustment link in a sample of Mexican-origin adolescents. We expected these hypotheses to apply to the between-persons level of analysis given prior research; no specific hypotheses were forwarded for the within-person and cross-level moderation effects in the discrimination—mental health association given the novelty of this analytic strategy. Age, gender, and nativity status were included as covariates, given prior research showing variations by age, gender, or nativity status in perceived discrimination (Córdova & Cervantes, 2010; Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000; Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008) and gender differences in internalizing and externalizing problems (Rescorla et al., 2007).

Method

Participants

At Time 1, the data analytic sample comprised 269 Mexican-origin adolescents, 12–17 years old (Mage = 14.1 years, SD = 1.6). At Time 2 and also at Time 3, the data analytic sample was 246 Mexican-origin adolescents. The data came from a 3-wave longitudinal study of discrimination and mental health in Mexican-origin adolescents and their families (Park et al., 2017). As reported in Park et al. (2017), the youth sample was 57% female (n = 153), with the majority born in the U.S. (71%; n = 191) and the remainder born in Mexico (29%; n = 78). The length of U.S. residency ranged from 2.4 months to 17 years (M = 12.6; SD = 3.0), with youth participants having spent, on average, 89.3% of their lives in the United States. Among those born in Mexico, the average length of U.S. residency was 10.3 years (SD = 3.7). In terms of family structure, 88.5% (n = 238) of the youths reported living in two-parent households. For annual household income, median income for fathers (via mother’s report) was $20,000–$29,999 (n = 232 valid responses) whereas median income for mothers (self-report) was below $20,000 (n = 262 valid responses). This suggests a combined household income that approaches the national median income level of $42,491 for Latino households (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015). More information regarding the youth sample at T1- T3 can be found in the Supplemental File, Table A.

Recruitment and Procedures

Adolescents and their families were recruited from public schools, churches, and community-based organizations in a mid-sized Midwestern region. The present study employed recommended recruitment and retention practices for Latino immigrant families (Martinez, McClure, Eddy, Ruth, & Hyers, 2012) and an ethnic-homogeneous design (Roosa et al., 2008), focusing on Mexican-origin families. Inclusion criteria were: 1) the family has an adolescent, age 12–17 years old, of Mexican descent; 2) residing with his/her biological mother, also of Mexican descent; 3) the adolescent’s biological father was also of Mexican descent. Exclusion criteria were: 1) the adolescent has a severe learning or developmental disability which would prevent them from understanding or responding to survey questions; and, 2) the family participated in the pilot study (2011–2012) which assessed similar constructs. For more details on the recruitment procedures, please refer to Park et al. (2017).

Data were collected from adolescents on three measurement occasions, spaced approximately 4 months apart (baseline, 4 months, and 8 months) from December 2013 through June 2015 over a period of 18 months at one of four community-based sites across two counties. At T1, 270 youths participated; at T2, 91.5% of youths (n = 247) were surveyed, and at T3, 91.5% of youths (n = 247) were surveyed; however, during the data cleaning phase, 1 family was discovered to not meet the eligibility criteria (father was not of Mexican origin). This family was dropped, leading to a final data analytic sample of 269 youths at T1, 246 youths at T2, and 246 youths at T3. Youths were required to have written parental permission and give informed assent. The target adolescent was then asked to independently complete a questionnaire in their preferred language (English or Spanish). At T1, 97.8% (263 out of 269 youths) completed the survey in English using an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) approach; 2.2% (6 youths) completed the survey in Spanish via face-to-face interview with a bilingual interviewer or Spanish language written questionnaire.

At T1, the first 44 participants received the copyrighted measures (the STAXI-2 C/A and YSR in the present study) via face-to-face interview (due to initial concerns about proprietary copyright regulations, which were later addressed) and public domain measures via ACASI, whereas the other 225 T1 participants received all measures in the ACASI format; all measures were administered in ACASI format in T2 and T3. T-tests indicated that there were no significant differences between the T1 participants who received the copyrighted measures via interview (n = 44) vs. ACASI (n = 225), except for externalizing problems [t(267) = −2.63, p < 0.01]. Thus, the present analyses controlled for survey mode when the outcome was externalizing problems as described in the Data Analytic Strategy section.

Participants who scored in the clinically elevated range on measures of psychological distress were debriefed by trained research staff and given information sheets and referrals to local mental health agencies; assistance was also offered in making an initial appointment with a service provider. Participating families received up to $190 as compensation for their total time in the project. The present study was approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board at the first author’s institution, and the identity of research participants was protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality (CC-MH-13-127) issued by the National Institute of Mental Health.

Measures

All measures in the present study were available in both English and in Spanish. For information on measurement invariance by age, please see Supplemental File, Appendix 2.

Demographic background

Age, gender, ethnicity, length of United States residency, birthplace, generation status, and family annual household income were assessed.

Perceived racial-ethnic discrimination

The Perceptions of Racism in Children and Adolescents instrument (PRaCY, short version; Pachter, Szalacha, Bernstein, & García Coll, 2010) is a self-report measure of adolescents’ perceived racial-ethnic discrimination, focusing primarily on direct instances (targeting the adolescent respondent) but also includes one item on vicarious discrimination (targeting parents or other family members). Originally developed and normed on a multicultural sample (predominantly Latino and African American) by Pachter et al. (2010), a Spanish version of the measure also exists and was available to participants in the present study. The PRaCY contains two 10-item versions for two age groups (8–13 year olds and 14–18 year olds), which differ only by two items; items have been shown not to be biased by age (Pachter et al., 2010). To reduce the potential problem of competing interpretations, the present study employed only the 8 PRaCY items that were common across the two age groups (this was deemed appropriate by L. M. Pachter, personal communication, February 04, 2016). Sample items include: “Have you ever been treated badly or unfairly by a teacher?” and “Have you ever seen your parents or other family members treated unfairly or badly because of the color of their skin, language, accent, or because they came from a different country or culture?” A dichotomous response format (“Yes”; “No”) was used in the present study. One point was assigned to all “yes” responses which were added to create a sum score (see Pachter et al., 2010). Internal consistency of the PRaCY was adequate in the present study, with Cronbach’s alphas of .70 (T1), .68 (T2), and .71 (T3).

Anger regulation

Two subscales from the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 Child/Adolescent version (STAXI-2 C/A; Brunner & Spielberger, 2009) assessed adolescents’ outward anger expression and anger suppression, respectively. The 5-item Anger Expression-Out subscale tapped how often the youth expressed anger towards objects or people in his/her environment through items such as: “I say mean things” (PAR, Inc., 2009). The 5-item Anger Expression-In (referred to as “anger suppression” in the present paper) scale tapped how often the youth tends to suppress or hold in angry feelings, through items such as: “I hide my anger” (PAR, Inc., 2009). Participants used a 3-point response format (1 = Hardly ever; 3 = Often) to rate each item. Mean scores were calculated for each subscale. Prior research has established adequate internal consistency of the STAXI-2 C/A subscales for female and male adolescents ages 12–18 years, with alphas in the .64 – .81 range (Brunner & Spielberger, 2009). In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas were as follows: Outward Anger Expression = .76 (T1), .75 (T2), .71 (T3); Anger Suppression = .68 (T1), .67 (T2), .73 (T3).

Ethnic identity

The Multi-group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney, 1992; Roberts et al., 1999) assessed adolescents’ ethnic identity using the 7-item affirmation, belonging, and commitment subscale and the 5-item exploration subscale. The MEIM is the most frequently used measure of ethnic identity, was designed for adolescents, and focuses on developmentally salient ethnic identity processes (Schwartz et al., 2014). Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), youths rated the degree to which they agreed with each statement. The commitment subscale consists of statements that inquire about feelings regarding, and reactions to, one’s ethnicity. A sample item from the affirmation/belonging/commitment subscale is: “I am happy that I am a member of the group I belong to.” The exploration subscale consists of statements describing how individuals explore, learn about, or participate in their ethnic group. A sample item from the exploration subscale is: “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs.” The 2-factor structure for the MEIM has been supported through recent confirmatory factor analysis evidence and prior research (e.g., Feitosa, Lacerenza, Joseph, & Salas, in press; Schwartz et al., 2014). Roberts and colleagues obtained adequate reliability for the MEIM subscales, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .81 – .88 for the affirmation/belonging/commitment subscale and from .57 – .73 for the exploration subscale across different ethnic populations; among Mexican Americans, Cronbach’s alphas were reported as .82 for the affirmation/belonging/commitment subscale and .58 for the exploration subscale (Roberts et al., 1999). The MEIM has been used successfully with Latino adolescents in prior research (e.g., Fuligni, Kiang, Witkow, & Baldelomar, 2008). In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas were slightly higher than those found by Roberts et al. (1999) for Mexican Americans. For the affirmation/belonging/commitment subscale, Cronbach’s alphas were: .88 (T1), .90 (T2), and .89 (T3); for the exploration subscale, Cronbach’s alphas were: .64 (T1), .69 (T2), and .66 (T3).

Social support

The 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988) is a widely used measure of perceived social support from three sources: family, friends, and a significant other. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Very Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Very Strong Agree). This measure has been shown to be valid and reliable among Mexican American adolescents (Edwards, 2004). Mean scores for the Family, Friends, and Significant Other subscales (4 items each) were computed as recommended by Zimet et al. (1988). Sample items from the three subscales include: “My family really tries to help me” (Family); “I can talk about my problems with my friends” (Friends); and, “There is a special person who is around when I am in need” (Significant Other). In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas were as follows: Family Subscale = .87 (T1), .91 (T2), and .91 (T3); Friends Subscale = .91 (T1), .91 (T2), and .90 (T3); Significant Other Subscale = .85 (T1), .87 (T2), and .89 (T3).

Externalizing problems

The 112-item Youth Symptom Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to assess youths’ report of externalizing problems. The YSR is a widely used measure with well-established reliability and validity that inquires about problem behaviors in the past 6 months including the present. Externalizing problems consists of two subscales: Rule-breaking Behavior (14 items) and Aggressive Behavior (17 items). Each item was rated using a 3-point scale (0 = Not True; 2 = Very True or Often True). As in prior research using the YSR (Rescorla et al., 2007), untransformed raw scores were used. The Externalizing problems score was calculated by summing the scores of the Aggressive Behavior and the Rule-breaking Behavior subscales. Internal consistency was adequate in the present study with Cronbach’s alpha = .88 (T1), .85 (T2), and .85 (T3).

Internalizing problems

The 112-item Youth Symptom Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to assess youths’ report of internalizing problems. The YSR is a widely used measure with well-established reliability and validity that inquires about problem behaviors in the past 6 months including the present. Internalizing problems consists of three subscales: Anxious/Depressed (13 items), Withdrawn/Depressed (8 items), and Somatic Complaints (10 items). Each item was rated using a 3-point scale (0 = Not True; 2 = Very True or Often True). As in prior research using the YSR (Rescorla et al., 2007), untransformed raw scores were used. The Internalizing problems score was calculated by summing the scores of the three subscales. Internal consistency for the Internalizing problems measure was adequate in the present study with Cronbach’s alpha = .89 (T1), .89 (T2), and .91 (T3).

Data Analytic Strategy

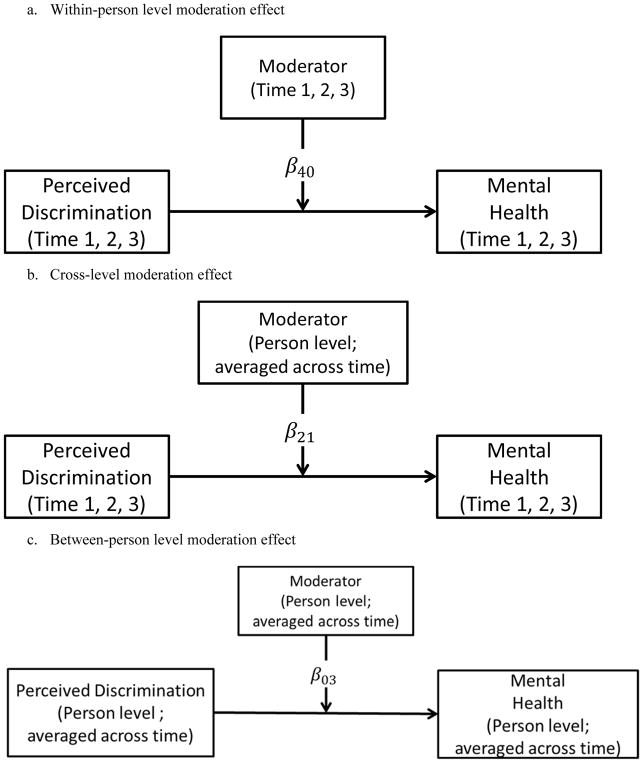

To test the study hypotheses regarding the moderating effects of ethnic identity, social support, and anger regulation in the link between racial-ethnic discrimination and adjustment in this sample of Mexican-origin youths, we conducted the moderation analyses using multilevel modeling (see Fig. 1). Multilevel modeling was used because the involved variables are all time-varying and thus the data had a two-level structure such that the three waves were nested within individuals (Hox, 2010; Preacher et al., 2006; Preacher et al., 2016; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Singer & Willett, 2003). In the present study, the Level-1 (L1) analysis unit was represented by time (3 waves), and the Level-2 (L2) analysis unit was represented by individual adolescents.

Figure 1.

Illustrative path diagrams of the different kinds of moderation effects.

Although tests of moderation have become increasingly common within the context of multilevel modeling, several problems currently exist due to conflation of effects across levels of analysis which leads to misleading results and an inability to interpret results accurately (e.g., Preacher et al., 2016). In this study, we apply ideas proposed in Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006), Raudenbush and Bryk (2002), and more recently in Preacher, Zhang, and Zyphur (2016) to estimate and test level-specific and cross-level moderation effects using multilevel modeling (see Figure 1). This approach not only yields more accurate and interpretable results but also has implications for more precisely specifying theory as well as intervention and policy recommendations at the appropriate levels of analysis. To obtain level-specific and cross-level moderation effects, person-mean centering was applied to the input and moderator variables to disaggregate between-person and within-person relations, given that disaggregation is required for correctly understanding the relations between a time-varying predictor and a time-varying outcome (Curran & Bauer, 2011; L. Wang & Maxwell, 2015).

Between-person vs. within-person relations

Using the relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems as an example, the between-person relation indicates the degree to which adolescents who experience more discrimination differ in externalizing problems from those who experience less discrimination. In contrast, the within-person relation indicates the degree to which an adolescent has more externalizing problems when he or she perceives more (or less) discrimination than when he or she does not. Therefore, the between-person relation shows how the two variables link across individuals, whereas the within-person relation reflects how the two variables link within an individual over time. With longitudinal data, we are able to disaggregate the two effects and better understand the relations between two time-varying variables. Accordingly, the moderation effects can occur at the between-person and within-person levels, in addition to cross-level effects, which will be explained in more detail below (see Figure 1). All analyses controlled for Time 1 youth age, gender, and nativity status. In addition, survey mode was controlled for when the outcome was externalizing problems. SAS PROC MIXED was used for fitting the multilevel models. We used all available data in the data analyses. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate the parameters in the multilevel moderation models, assuming that the missingness mechanism was missing at random (Little & Rubin, 2014).

Equations for multilevel moderation models

The multilevel moderation models, using externalizing problems as an example for the outcome variable and ethnic identity commitment as a moderator, are described below:

Level-1 equation

where EPij (Externalizing Problems; outcome variable), PRaCYij (Perceived discrimination, predictor variable), and MEIMij (Ethnic identity commitment, moderator) are the observed scores for individual i at time j, respectively. Variablei· is the individual i’s person mean of the variable, which is included for person-mean centering as a measure of individual i’s person level of the variable. Variablei· can be used as a level-2 variable. Therefore, a2i and a3i measure the within-person main effects of perceived discrimination and ethnic identity commitment on the outcome for individual i respectively, whereas a4i measures the interaction (moderation) effect at the within-person level for individual i.

As documented in prior longitudinal research (Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002), testing effects (e.g., decreasing means over time) were observed due to repeated administration of the study measures. Thus, time was also included as a level-1 covariate to linearly detrend the data (i.e., control for the linear effect of time), as recommended (Curran & Bauer, 2011; L. Wang & Maxwell, 2015).

Level-2 equations

At the second level, the random effects are predicted by the relevant person mean variables and the control variables (e.g., SMODE stands for survey mode). The inclusion of the person mean variables for each random effect follows the guidelines for multilevel moderation analysis with 1-1-1 designs (the predictor, moderator, and outcome variables are all Level-1 or time-varying variables), as suggested by Preacher, Zhang, and Zyphur (2016; see Equation 6).

From the multilevel moderation model, we were interested in evaluating the following three fixed-effects moderation effects after controlling for the covariates. They are (1) β40, the average within-person level moderation effect (see Figure 1a), quantifying how the time-varying ethnic identity commitment variable moderates the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems; (2) β21, a cross-level moderation effect (Figure 1b), quantifying how person levels of ethnic identity commitment moderate the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems; and (3) β03, the between-person level moderation effect (Figure 1c), quantifying how person levels of ethnic identity commitment moderate the between-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems.

Conceptually, the within-person level moderation effect, β40, tells us whether the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems is, on average, stronger or weaker when the person has a stronger ethnic identity commitment. The cross-level moderation effect, β21, tells us whether a person with a higher average level of ethnic identity commitment has a stronger or weaker within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems than another person with a lower average level of ethnic identity commitment. In contrast, the between-person level moderation effect, β03, tells us whether a person with a higher average level of ethnic identity commitment has a stronger or weaker between-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems than another person with a lower average level of ethnic identity commitment. Thus, the three kinds of moderation effects are conceptually different and important to distinguish. With longitudinal data and multilevel modeling, we were able to evaluate all three of these types of multilevel moderation effects and understand their different origins within and across levels of analysis.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The correlations, means, and standard deviations of the study variables at T1, T2, and T3, respectively, can be found in the Supplemental File, Table B.

Multilevel Moderation Models

The results from the multilevel moderation analyses are displayed by mental health outcome (i.e., externalizing problems and internalizing problems, respectively) in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results from Multilevel Moderation Analyses by Mental Health Outcome

| Moderator |

β40 Within-person |

β21 Cross-level |

β03 Between-person |

|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing problems | |||

| Anger-Out | 3.33 (.032)* | .17 (.004) | .03 (.622) |

| Anger Suppression | 1.54 (.159) | −.11 (.131) | −.25 (.001) |

| Ethnic Identity Commitment | −14.16 (.018) | −.48 (.045) | −.53 (.054) |

| Ethnic Identity Exploration | −7.65 (.030) | −.58 (.022) | −.20 (.517) |

| Social Support | |||

| Family | −8.32 (.048) | −.37 (.007) | −.05 (.744) |

| Friends | −1.30 (.682) | −.32 (.030) | .18 (.221) |

| Sig Other | −.67 (.791) | −.53 (.001) | −.02 (.898) |

| Internalizing problems | |||

| Anger-Out | 2.64 (.081) | .17 (.004) | .02 (.734) |

| Anger Suppression | 1.04 (.490) | .11 (.247) | .13 (.178) |

| Ethnic Identity Commitment | 2.28 (.772) | −.29 (.374) | −.24 (.493) |

| Ethnic Identity Exploration | 5.13 (.254) | −.28 (.415) | .64 (.120) |

| Social Support | |||

| Family | 2.15 (.529) | −.43 (.013) | −.21 (.242) |

| Friends | 2.15 (.473) | −.17 (.332) | −.11 (.552) |

| Sig Other | 2.76 (.408) | −.69 (.001) | .01 (.947) |

Note: β40 represents the average within-person level moderation effect, quantifying how the time-varying moderator moderates the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and the outcome; β21 is a cross-level moderation effect, quantifying how person levels of the moderator moderate the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and the outcome; and β03 measures the between-person level moderation effect, quantifying how person levels of the moderator moderate the between-person relation between perceived discrimination and the outcome. Anger-Out = Outward Anger Expression; Sig Other = Significant Other. The values outside the parentheses are the point estimates, and the values inside the parentheses are p values; p values < .05 have been bolded. The missing data handling method was full information likelihood estimation.

This result became statistically non-significant (p = .06) when a truncated version of the Externalizing Problems measure was used as explained in the Results section.

Externalizing problems

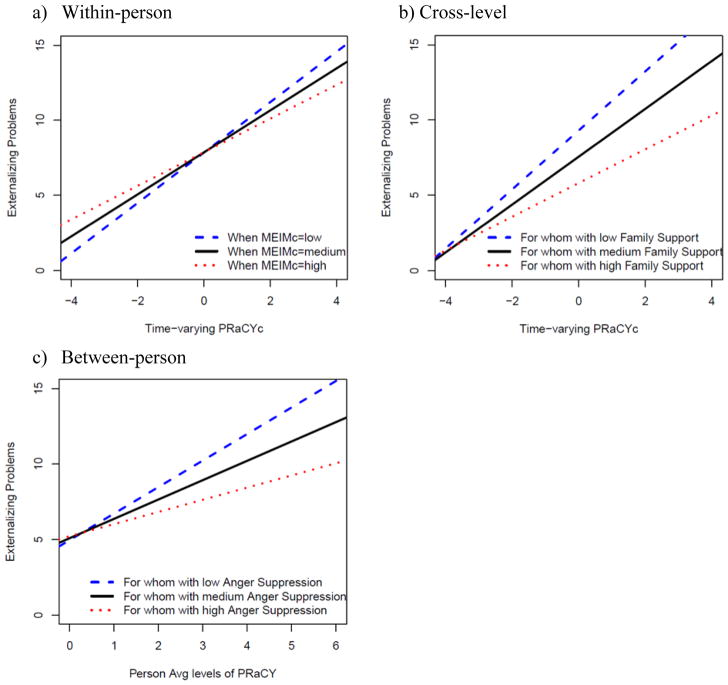

For the average within-person level moderation effects (β40), time-varying outward anger expression, ethnic identity commitment, ethnic identity exploration, and family support significantly moderated the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems. More specifically, when a youth had more frequent outward anger expression, the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems was significantly exacerbated than when the youth had less frequent outward anger expression (estimate = 3.33, p = .032; see Table 1). In contrast, when a youth had higher levels of ethnic identity commitment, ethnic identity exploration, or family support, the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems was significantly attenuated than when the youth had lower levels of ethnic identity commitment, exploration, or family support (estimates = −14.16, −7.65, and −8.32, ps = .018, .030, and .048, respectively; see Table 1). As an example of a within-level moderation effect, Figure 2a illustrates the buffering effect of ethnic identity commitment on the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems. Time-varying anger suppression, support from friends, or support from significant others did not significantly moderate the within-person relations between discrimination and externalizing problems.

Figure 2.

Graphic display of the three kinds of moderation effects. a) The within-person moderation effect graph shows that when the time-varying ethnic identity commitment level is higher, the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems is weakened; b) the cross-level moderation effect graph shows that the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems is weakened for whom—those with higher average levels of family social support; and c) the between-person moderation effect graph shows that the between-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems is weakened for whom—those with higher average levels of anger suppression. PRaCYc = person-mean centered PRaCY (perceived discrimination). MEIMc = person-mean centered MEIM (ethnic identity commitment).

With regard to the cross-level moderation effects (β21), person levels of outward anger expression, ethnic identity commitment, ethnic identity exploration, family support, friends’ support, and significant other support significantly moderated the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems (whereas person levels of anger suppression did not significantly moderate this link). More specifically, a youth with a higher average level of outward anger expression had a significantly stronger within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems than another youth with a lower average level of outward anger expression (estimate = .17, p =.004; see Table 1). In contrast, the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems was significantly attenuated for youths with higher average levels of ethnic identity commitment, exploration, family support, friend support, and significant other support, respectively (estimates = −.48, −.58, −.37, −.32, −.53, ps = .045, .022, .007, .030, and .001, respectively; see Table 1). As an example of a cross-level moderation effect, Figure 2b illustrates the buffering effect of family support on the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems.

With regard to the between-person level moderation effects (β03), only person levels of anger suppression significantly moderated the between-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems such that the between-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems was attenuated for youths with a higher (versus lower) average level of anger suppression (estimate = −.25, p = .001; see Figure 2c).

Finally, to ensure that outward anger expression did not overlap with the assessment of externalizing problems, the analyses were re-run using a shortened version of the externalizing problems measure in which 3 items were dropped; these 3 items (from the Aggressive Behavior subscale of the externalizing problems measure) were similar in content to items on the outward anger expression subscale. When the shortened version of the externalizing problems measure was used, the significant moderating effect of outward anger expression at the within-person level became statistically non-significant (estimate = 2.63; p = .060); however, the pattern of moderating results for outward anger expression vis-à-vis externalizing problems at the cross-level and between-person level remained consistent with those found above. Note: With regard to how the moderation effects varied across age, gender, and nativity status when externalizing problems was the outcome, please see Supplemental File, Appendix 1.

Internalizing problems

In contrast to the parallel results for externalizing problems, none of the average within-person level moderation effects were significant for internalizing problems. However, the cross-level moderation effects for internalizing problems were generally similar to (though fewer than) those for externalizing problems. For example, for youths with a higher (versus lower) average level of outward anger expression, the within-person effect of perceived discrimination on internalizing problems was significantly exacerbated or strengthened (estimate = .17, p =.004; Table 1). Furthermore, the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and internalizing problems was significantly attenuated for youths with higher average levels of family support and significant other support (estimates = −.43 and −.69, ps =.013 and .001, respectively; Table 1). Finally, none of the average between-person level moderation effects were significant for internalizing problems.

Discussion

The purpose of the present three-wave longitudinal study was to test whether and how ethnic identity, perceived social support, and anger regulation moderated the association between perceived racial-ethnic discrimination and adjustment in a Midwestern sample of Mexican-origin adolescents. Specifically, we pitted competing hypotheses against one another regarding the role of these three coping strategies in either buffering or exacerbating the adverse effect of discrimination on Latino adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing problems. Though these coping strategies represent diverse fields such as identity development and emotion regulation, the current study bridged these literatures through one integrative conceptual model that shows how a stress and coping perspective can be fruitfully applied to the problem of coping with discrimination and racism. The application of a new multilevel modeling approach for testing moderation within and across levels of analysis afforded a more nuanced and less biased examination of these putative psychological moderating variables within and between individuals over time. Results indicated that greater ethnic identity commitment and exploration, greater perceived social support, and more frequent anger suppression tended to buffer youths in the link between discrimination and adjustment problems, whereas more frequent outward anger expression tended to exacerbate the association between discrimination and adjustment problems. Importantly, however, these significant moderating effects varied as a function of the level of analysis, and the decomposition of these moderating effects is examined more closely below. The current study not only represents the first empirical test of Brondolo et al.’s (2009) conceptual model of coping strategies involved in dealing with racism, but also represents the first time a multilevel moderation modeling approach has been applied to the health disparities problem of the discrimination—mental health link and sources of risk and resilience therein.

What Buffers? What Exacerbates? At What Level?

Typically, prior research on moderators in the discrimination-adjustment link has tended to comprise single-level, cross-sectional studies (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009); in such cases, the only possible moderating tests are at the between-person level, which answers the question, “for whom?” In the present study, the only significant between-person level interaction effect involved anger suppression as a significant buffer in the association between discrimination and externalizing problems. That is, among youths who used more (vs. less) frequent anger suppression, the relation between discrimination and externalizing problems was attenuated (see Figure 2c); in other words, for these Mexican-origin adolescents, anger suppression was an effective coping strategy that protected them from developing externalizing behaviors. This finding runs counter to the notion that anger suppression is typically associated with greater psychopathology (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). Why might anger suppression be beneficial? It may be more adaptive for youths facing discrimination to conceal their anger. The ability to flexibly suppress emotions based on contextual demands or threat has been shown to be associated with better adjustment outcomes (e.g., Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Westphal, & Coifman, 2004) because this regulatory flexibility can indicate abilities related to sensitivity to context and a wide ranging repertoire of emotion regulation strategies. No significant between-person moderating effects were found for ethnic identity or social support. These null findings may be due to the relatively high mean scores on these measures suggesting ceiling effects or restricted between-person variability and the limited ability to detect between-person moderation effects, an issue that has been addressed in prior studies of ethnic identity processes (e.g., Yip, 2014; Douglass, Wang, & Yip, 2016).

At the within-person level, four significant moderators were found. Ethnic identity exploration, ethnic identity commitment, and family support, respectively, buffered youths in the link between discrimination and externalizing problems. Outward anger expression exacerbated the discrimination—externalizing problems link; however, this effect only reached a trend level of significance (p = .06) when three items that overlapped with the outward anger expression subscale were dropped from the Externalizing Problems measure. More specifically, these time-varying moderators answer the question, “when?” in the relation between discrimination and externalizing problems within a given adolescent over time. That is, when a given Mexican-origin adolescent has undergone more (vs. less) ethnic identity exploration and commitment, respectively, the adverse influence of that particular youth’s experience of discrimination on externalizing problems will be attenuated, as hypothesized. Thus, ethnic identity exploration and commitment may provide these youths with additional psychological or social resources that enables more effective coping with discrimination experiences. Similarly, at the within-person level, the buffering effect of family support may be interpreted as follows: when a given Mexican-origin adolescent perceives greater family support, that youth’s experience of discrimination will be less likely to be associated with externalizing problems (a buffering effect of family support, as hypothesized). Given the cultural value of familismo (Ayón, Marsiglia, & Bermudez-Parsai, 2010; Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda, & Yoshikawa, 2013) and the related priority placed on family, family loyalty, interconnectedness in Latino culture, this coping resource is not surprising, as Mexican-origin youths would view their family as a natural support system.

The within-person level findings are reminiscent of some existing evidence indicating the buffering effects of ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2012) or family support (Potochnick & Perreira, 2010) among Latino adolescents coping with discrimination. Importantly, unlike prior research, the present study results introduce a paradigm shift in conceptualizing and operationalizing significant moderation effects within and across levels of analysis. At the within-person level, the interpretation becomes especially salient in better understanding how these protective or risk factors operate and unfold within a given individual across time.

Finally, the cross-level results indicated six significant moderators (outward anger expression, ethnic identity commitment, ethnic identity exploration, family/friend/significant other support) of the discrimination—externalizing problems link and three significant moderators (outward anger expression, family support, significant other support) of the discrimination—internalizing problems link. For both externalizing and internalizing outcomes, outward anger expression was a risk factor (exacerbating the effect of discrimination), whereas ethnic identity exploration and commitment and all sources of social support, were protective factors (weakening the effect of discrimination, as hypothesized) for this sample of Mexican-origin youths. As with between-person level effects, these significant moderators signal “for whom” the discrimination—adjustment association is stronger or weaker. However, cross-level effects examine the discrimination—adjustment relation across time, whereas between-person level effects assess the discrimination—adjustment relation between groups of individuals. For example, for youths with a higher (vs. lower) level of family support, the within-person relation between perceived discrimination and externalizing problems will be attenuated across time. For internalizing problems, the cross-level analysis seems particularly relevant, as the only significant moderators appeared at this level. It may be especially important to examine moderators at a person level, while examining how the discrimination—adjustment association unfolds across time when internalizing problems (such as depression or anxiety) are concerned, compared to the other two levels of analysis (i.e., within-person or between-person).

Taken together, the present findings partially support our hypotheses and reveal several sources of resilience (and risk) that may have remained hidden, apart from the use of a multilevel moderation analytical strategy. At the between-person level, only one significant moderator was detected (anger suppression attenuated the discrimination—externalizing problems link), whereas three significant moderators were found at the within-person level, and nine significant moderators were found when testing cross-level interactions. Thus, relying solely on a between-person approach may be limiting the discovery of potential buffers in the discrimination—adjustment link. It appears that testing cross-level interactions may be especially fruitful. Congruent with our initial hypotheses, ethnic identity and social support attenuated the link between discrimination and adjustment problems, though primarily using within-person and cross-level analyses for which we originally did not generate specific hypotheses given insufficient prior research. Importantly, the significant moderating results found in the within-person and cross-level analyses represent new knowledge and a starting point for future researchers to then develop empirically-based hypotheses about sources of risk and resilience using similar analytic strategies in the area of discrimination and health disparities.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The present study contributes to the literature on racial-ethnic discrimination and coping in several ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, the current study represents the first empirical test of Brondolo et al.’s (2009) integrative conceptual model on coping strategies that may buffer the discrimination—adjustment link, specifically, in a sample of Latino adolescents. Second, the longitudinal design afforded the opportunity to examine different kinds of moderation effects. The novel application of Preacher et al.’s (2006) and (2016) method for decomposing multilevel moderation effects to the racism and mental health disparities literature allowed for a more nuanced, less biased examination of interaction effects within and across levels of analysis. Finally, the present study’s sample, in terms of developmental stage (adolescence), geographic location (Midwestern region, representing a relatively new immigrant settlement area, in contrast to more traditional gateway metropolitan areas in California, New York, or the Southwestern U.S.), and ethnic-homogenous (Mexican-origin) design provides more data points within the current empirical knowledge base for greater representation, diversity, and clarity in the interpretation of culture-specific (and context-specific) results. For example, prior research has highlighted the importance of social context and geography when studying the experiences of discrimination and ethnic identity among Latino adolescents (e.g., Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). Thus, results from the present study can apply to Mexican-origin adolescents in the Midwest, which represents a unique ecological niche where Mexican Americans may not be in the numerical majority, compared to more diverse places.

At the same time, these current findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First and foremost, the conceptual model that was tested in the present study focused on individual-level coping strategies in the face of racism and discrimination. Yet, we believe that it is imperative to acknowledge the systemic and multi-faceted nature of the problem of racism, which then requires macro-level changes within institutions and society as a whole to address in a comprehensive manner. Thus, we are not endorsing a victim-blame analysis with the present study’s focus on coping strategies. Rather, we hope that examining individual-level coping strategies can inform future interventions at individual and other levels as described below. Second, although the study was theoretically anchored in a conceptual model of racism and coping, this necessarily limited the scope of the coping strategies that were tested to a select few. In the future, additional coping strategies such as engagement vs. disengagement coping strategies, cognitive processes, racial-ethnic socialization, and religious involvement (Lewis et al., 2015) should be interrogated. Second, the perceived discrimination measure included a dichotomous yes-no response format; future research should examine the nature of the discrimination experience in greater detail, such as whether and how the frequency of discrimination interacts with various coping strategies to affect adolescent mental health. Third, the study’s generalizability is restricted given the convenience sampling method used; however, these data should still be useful in contributing to the limited knowledge base on Mexican-origin adolescents who reside in the Midwest. Lastly, given that the eligibility criteria for the current study required that both parents participate, the resulting sample was probably more resilient compared to adolescents from one-parent households. Yet, these findings also reflect a conservative test of the research hypotheses given the strict criteria for inclusion into the study.

Implications for Future Research, Theory, and Practice

The present study’s multilevel moderation results have implications at, accordingly, multiple levels for future research, theory, and practice. First, as a general recommendation, future studies examining potential moderating effects with longitudinal data should consider the application of methods which allow for the assessment of moderation within and across levels of analysis (Preacher et al., 2006; Preacher et al., 2016). More specifically, as more multilevel moderation studies are generated, the particular findings presented in the current study regarding the buffering or exacerbating effects of ethnic identity, social support and anger regulation should be tested in both Latino and other racial-ethnic minority populations to see whether or not the findings can be replicated and how these coping strategies may change or evolve across the lifespan. Second, with regard to future theory-building, greater precision and specificity can either be embedded into current conceptual models of the role of moderators in the discrimination—health link or make possible the envisioning of entirely new multilevel models that parse apart components of interaction effects within and across levels of analysis. Third, future research should consider and assess the role of intergroup contact and school diversity, as these variables have been shown to influence the discrimination experiences of ethnic minority youths (e.g., Brown & Chu, 2012; Ruck, Park, Killen, & Crystal, 2015). For example, youths of color who are in racially diverse schools or schools where they are the numeric majority may have different experiences with discrimination and use potentially different coping strategies than their counterparts in numeric minority contexts (e.g., Brown & Chu, 2012; Ruck et al., 2015).

Third, because of their precision with regard to levels of analysis, the current results may have more pointed implications for interventions targeting individuals in clinical settings. For instance, the moderators found to be significant at the cross-level and within-person level analyses are applicable to interventions targeting individuals. Thus, because ethnic identity exploration and commitment were found to serve as buffers against the adverse influence of discrimination on externalizing problems at the within-person level, clinicians working with a given Mexican-origin adolescent dealing with discrimination may consider encouraging ethnic identity exploration and bolstering his/her ethnic identity commitment in order to lessen the risk of developing externalizing problems over time.

In sum, by identifying ethnic identity, social support from family, friends, or significant others, and anger suppression as effective coping strategies in the discrimination—adjustment link among Latino youths, this study points to coping strategies that can help inform future prevention and intervention efforts aimed at mitigating the detrimental impact of racism on Latino youths’ well-being. Because the present study employed an innovative analytical method for decomposing multilevel moderation effects, the results also elucidate the specific level at which significant interactions occur, allowing for clearer interpretation and application of the results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21MH097675 (Irene Park, Principal Investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We want to thank all of the participating youths and families and partnering community-based agencies. We thank these research team members for their contributions: Rosemary Salinas, Misel Ramirez Vasoli, Amarilys Castillo, Jaqueline Martinez, Kristina Martinez, Margaret Schmid, Carlos Uzcategui, and Kimberly Widawski. We also thank our consultants: Gilberto Pérez, Jr., M.S.W., A.C.S.W. for his community liaison work and Jennifer Burke-Lefever, Ph.D. for her guidance on project implementation.

Contributor Information

Irene J. K. Park, Indiana University School of Medicine – South Bend

Lijuan Wang, University of Notre Dame.

David R. Williams, Harvard University

Margarita Alegría, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ai AL, Aisenberg E, Weiss SI, Salazar D. Racial-ethnic identity and subjective physical and mental health of Latino Americans: An asset within? American Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;53(1–2):173–184. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9635-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1007/s10464-014-9635-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Marsiglia FF, Bermudez-Parsai M. Latino family mental health: Exploring the role of discrimination and familismo. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38(6):742–756. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein J, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, Saenz D. Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(4):893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Burton CL. Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(6):591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Westphal M, Coifman K. The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science. 2004;15(7):482–487. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, ver Halen NB, Pencille M, Beatty D, Contrada RJ. Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Chu H. Discrimination, ethnic identity, and academic outcomes of Mexican immigrant children: The importance of school context. Child Development. 2012;83(5):1477–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01786.x. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner TM, Spielberger CD. STAXI-2 C/A: State-trait expression inventory-2 child and adolescent professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Yoshikawa H. Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. Journal of Family Issues. 2013;34(12):1696–1724. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1177/0192513X12460218. [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, … Szapocznik J. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence. 2015;42:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Hitter TL, Adams EM, Williams C. Minority stress and depressive symptoms: Familism, ethnic identity, and gender as moderators. The Counseling Psychologist. 2016;44(6):841–870. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1177/0011000016660377. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. The American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Gary M, Coups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, … Chasse V. Ethnicity-related sources of stress and their effects on well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(4):136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D, Cervantes RC. Intergroup and within-group perceived discrimination among U.S.-born and foreign-born Latino youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2010;32(2):259–274. doi: 10.1177/0739986310362371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, Dahl RE. Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13(9):636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1038/nrn3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, editor. Income and poverty in the United States: 2014. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2015. (Current Population Reports, P60–252 ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Dorr N, Brosschot JF, Sollers JJ, III, Thayer JF. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: The differential effect of expression and inhibition of anger on cardiovascular recovery in Black and White males. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2007;66(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass S, Wang Y, Yip T. The everyday implications of ethnic-racial identity processes: Exploring variability in ethnic-racial identity salience across situations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(7):1396–1411. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dover T, Major B, Kunstman J, Sawyer P. Does unfairness feel different if it can be linked to group membership? Cognitive, affective, behavioral and physiological implications of discrimination and unfairness. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2015;56:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM. Measuring perceived social support in Mexican American youth: Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(2):187. doi: 10.1177/0739986304264374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feitosa J, Lacerenza CN, Joseph DL, Salas E. Ethnic identity: Factor structure and measurement invariance across ethnic groups. Psychological Assessment, Nov 28, 2016. 2016 doi: 10.1037/pas0000346. No Pagination Specified. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pas0000346. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(3):295–313. doi: 10.2307/2676322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Kiang L, Witkow MR, Baldelomar O. Stability and change in ethnic labeling among adolescents from Asian and Latin American immigrant families. Child Development. 2008;79(4):944–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng C, Kiviniemi M, O’Hara RE. Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? what buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(5):785. doi: 10.1037/a0019880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng C, Wills TA. The erosive effects of racism: Reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in african american adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(5):1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1037/a0027404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez LM, Stein GL, Kiang L, Cupito AM. The impact of discrimination and support on developmental competencies in Latino adolescents. Journal of Latina/o Psychology. 2014;2(2):79–91. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1037/lat0000014. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”?: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. 2. New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, New York, NY; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2015;11:407–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, McClure HH, Eddy JM, Ruth B, Hyers MJ. Recruitment and retention of Latino immigrant families in prevention research. Prevention Science. 2012;13(1):15–26. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hilt LM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Racial-ethnic differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology: An Official Publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2007;35(5):801–816. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9128-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina KM, Jackson B, Rivera-Olmedo N. Discrimination, Racial-ethnic identity, and substance use among Latina/os: Are they gendered? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;50:119. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9738-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(3):295–303. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x. [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, García Coll C. Racism and child health: A review of the literature and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(3):255–263. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ed5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Szalacha LA, Bernstein BA, García Coll C. Perceptions of racism in children and youth (PRaCY): Properties of a self-report instrument for research on children’s health and development. Ethnicity & Health. 2010;15(1):33–46. doi: 10.1080/13557850903383196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IJK, Wang L, Williams DR, Alegría M. Does anger regulation mediate the discrimination-mental health link among Mexican-origin adolescents? A longitudinal mediation analysis using multilevel modeling. Developmental Psychology. 2017;53:340–352. doi: 10.1037/dev0000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36(4):421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick SR, Perreira KM. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198(7):470–477. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e4ce24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/10769986031004437. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ. Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychological Methods. 2016;21(2):189–205. doi: 10.1037/met0000052. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1037/met0000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L, Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, Dumenci L, Almqvist F, Bilenberg N, … Verhulst F. Epidemiological comparisons of problems and positive qualities reported by adolescents in 24 countries. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(2):351–358. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.351. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, … Yip T. Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development. 2014;85(1):40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1111/cdev.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Syed M, Umaña-Taylor A, Markstrom C, French S, Schwartz SJ, Lee R. Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta-analysis of positive ethnic–racial affect and adjustment. Child Development. 2014;85(1):77–102. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12175. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.nd.edu/10.1111/cdev.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19(3):301–322. [Google Scholar]