Abstract

MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that inhibit gene expression post-transcriptionally, implicated in virtually all biological processes. Although the effect of individual microRNAs is generally studied, the genome-wide role of multiple microRNAs is less investigated. We assessed paired genome-wide expression of microRNAs with total (cytoplasmic) and translational (polyribosome-bound) mRNA levels employing Frac-seq in human primary bronchoepithelium from healthy controls and severe asthmatics. Severe asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by poor response to therapy. We found genes (=all isoforms of a gene) and mRNA isoforms differentially expressed in asthma, with novel inflammatory and structural pathophysiological mechanisms related to bronchoepithelium disclosed solely by polyribosome-bound mRNAs (e.g., IL1A and LTB genes or ITGA6 and ITGA2 alternatively spliced isoforms). Gene expression (=all isoforms of a gene) and mRNA expression analysis revealed different molecular candidates and biological pathways, with differentially expressed polyribosome-bound and total mRNAs also showing little overlap. We reveal a hub of six dysregulated microRNAs accounting for ~90% of all microRNA targeting, displaying preference for polyribosome-bound mRNAs. Transfection of this hub in bronchial epithelial cells from healthy donors mimicked asthma characteristics. Our work demonstrates extensive post-transcriptional gene dysregulation in human asthma, where microRNAs play a central role, illustrating the feasibility and importance of assessing post-transcriptional gene expression when investigating human disease.

Keywords: alternative splicing, asthma, bronchoepithelium, microRNA, polyribosome, RNA-seq, translation

Introduction

MicroRNAs are small regulatory molecules (~22 nucleotides long) that inhibit gene expression by pairing mainly to the 3’ UTRs (UnTranslated Region) of their target mRNAs (1). MicroRNA effects include mRNA destabilization and inhibition of translation, with a body of literature supporting both as main effector mechanisms (2–5). The biological relevance of microRNAs expands to most cellular processes, as thousands of mRNAs contain microRNA responsive elements (MREs). Consequently, microRNA dysregulation has been demonstrated to underlie disease pathophysiological mechanisms, making microRNAs novel therapeutic targets (6).

Although the effects of individual microRNAs in disease have been explored extensively, there are fewer reports on the role of microRNAs acting as networks in this setting. We have previously shown that microRNAs dysregulated in asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells may have different effects- even opposite- when modulating their levels individually vs simultaneously (7). Our work and others (8) highlight the need for integrative genome-wide approaches to understand the role and importance of microRNAs in cellular and pathological processes.

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disease of the airways affecting ~350 million people worldwide and with a spectrum of severity. Severe asthma (SA) is characterized by the need for or the failure to respond to high dose glucocorticoids in conjunction with other additional controller therapies (9). The underlying mechanisms of severe asthma remain incompletely understood and it therefore represents a major unmet clinical need, accounting for the majority of the healthcare budget dedicated to asthma. Current therapy for asthma targets the inflammatory and smooth muscle constrictor components of the disease. Since severe asthma patients remain uncontrolled it is probable that additional mechanisms or steroid-unresponsive processes contribute to the disease persistence. As the airway epithelium orchestrates both inflammatory and remodeling processes relevant to severe asthma (10, 11), we have focused on investigating alterations in this cell population. Moreover, we have centered on investigating post-transcriptional control of gene expression in asthma given that post-transcriptional control is considered key in the regulation of inflammation (12) and requires further understanding in many diseases including asthma.

Popular approaches to studying complex diseases using high throughput methodologies focus on the transcriptome, measured with arrays and sequencing technologies. However, it is appreciated that gene transcription and gene translation are not synonymous. From transcription to translation into protein, mRNA undergoes multiple processes including splicing, stabilization, targeting by microRNAs and decay (13), which affect mRNA loading into polyribosomes and subsequent translation. It is well acknowledged that the transcriptome shows weak correlation with the corresponding protein levels, as has been noted in early work (14). More recent works (15–17) show that the weak correlation can be improved upon by a machine learning approach integrating transcript levels, transcript stability, polyribosome binding and other sequence-based proxies of translation rates. Thus, the disparity between mRNA and protein levels in a variety of systems reflects the relevance of post-transcriptional mRNA regulation, demonstrating that cytoplasmic mRNA expression inadequately reflects actual translation into protein (13, 18). This disparity is even more pronounced in mammalian cells because of mRNA splicing. Alternative splicing generates several mRNAs from one single gene, with virtually all genes undergoing splicing (19). Alternatively spliced mRNA isoforms show preferential binding to polyribosomes (20) and heavily influence protein levels (21). Together these observations highlight the need for consideration of splicing and translation when performing genome-wide mRNA expression measurements.

Given that microRNAs may affect mRNA levels and/or their translation into protein, as well as their importance in asthma, we sought to determine the genome-wide relationship between microRNAs and their mRNA targets in human asthma in different sub-cellular compartments. To this end, we performed microRNA profiling using small RNA-sequencing and integrated it with Frac-seq (20) in bronchial epithelial cells (BECs) isolated from human clinical samples from healthy volunteers and well-characterized severe asthmatic patients. Frac-seq combines subcellular fractionation and RNA sequencing, measuring mRNA levels in both cytoplasm (all mRNAs) and polyribosome bound (mRNAs undergoing translation) fractions (22), facilitating the study of post-transcriptional mRNA regulation on a genome-wide scale.

Our work presents for the first time evidence that global control of mRNA splicing and translation is at the centre of a human disease and asthma pathophysiology. Our results show that microRNAs are predicted to preferentially target polyribosome-associated mRNAs in asthma, adding valuable knowledge to the long-standing debate about microRNA effects on their targets (2, 5, 23, 24). More strikingly, amongst the microRNAs detected as differentially expressed between health and asthma, our results show that ~50% of the changes in mRNA binding to polyribosomes is modulated by a small hub of only six microRNAs. These six microRNAs account for ~90% of all cellular microRNA targeting and recapitulate disease characteristics when modulated in healthy cells. Our work highlights the relevance of studying microRNAs in their molecular and cellular context and demonstrates the feasibility and importance of studying post-transcriptional gene regulation in asthma, opening a novel path in the understanding of the asthmatic process and potentially other inflammatory pathologies.

Materials and Methods

Study volunteers and consent to participate

Non-smoking volunteers aged 18-65 years were recruited from the Wessex Severe Asthma Cohort and age/sex matched healthy controls from a departmental database (Supplemental Table 1). All participants gave written informed consent. Adults with no history of respiratory disease, no current symptoms and who did not achieve a 20% drop in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) with inhaled methacholine at 16mg/mL were defined as healthy controls. Severe asthma patients had inadequately controlled disease, (Asthma Control Questionnaire [ACQ] score of ≥1.5), despite management at Step 4/5 of the BTS/SIGN asthma guidelines (4 at step 5) and fulfilled the ERS/ATS criteria for severe asthma. The study had prior ethics approval from The Southampton and South West Hampshire local research ethics committee (REC reference number 05/Q1702/165). BECs used in the microRNA transfection experiments had also ethical approval (REC Number 06/Q0505/12).

Spirometry, bronchoscopy and cell culture

Spirometry was performed using the Jaeger Masterscreen with Viasys software. Measures were made before and 15 minutes after the administration of nebulised salbutamol (2.5mg).

Flexible bronchoscopy was undertaken as previously described (25) according to British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines and the local departmental standard operating procedure in the NIHR Respiratory Bioscience Research Unit (RBRU), which is part of the Southampton Centre for Biomedical Research (SCBR) at Southampton General Hospital (UK). Four separate sets of epithelial brushings were obtained from the right bronchus intermedius using disposable, sheathed bronchial brushes (Olympus BC-202D-1210). Brushings were spun in plain RPMI supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) at 1200 rpm 10 minutes, medium discarded and cells resuspended in complete BEGM (Lonza, Blackley, United Kingdom). Bronchial epithelial cells were cultured as previously described (7). Briefly, bronchial epithelial cells were cultured in collagen (Thermo Fisher Scientific)-coated T25 flasks in BEGM complete medium (Lonza) and passaged onto 15cm2 dishes when 80% confluent. All expression experiments were done in passage 1 cells. BECs employed in the microRNA transfection experiments were isolated as in (26) and were of passages 3-4.

Small RNA-sequencing

Libraries and small RNA sequencing were done in Ocean Ridge Biosciences (Florida, USA). Libraries were made employing NEBNext Small RNA-Seq Library Preparation Kit (New England Biolabs- Ipswich, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions and purified using a gel-based extraction method. The quality and size distribution of the amplified libraries were determined utilizing an Agilent 2100 High Sensitivity DNA Bioanalyzer microfluidic chip. Libraries were quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (KK4824, Kapa Biosystems, Boston, USA). Libraries were pooled at equimolar concentrations and diluted prior to loading onto the flow cell of the cBot cluster station (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Libraries were extended and bridge amplified to create single sequence clusters using the TruSeq Rapid SR Cluster Kit – HS. 10% ΦX174 phage DNA was spiked in all sequencing lanes for sequencer calibration. Real time image analysis and base calling were performed on the instrument using the HiSeq Sequencing Control Software version 2.0.12.0 (HCS). Libraries were sequenced with 50-bp single-end reads plus index read (TruSeq Rapid SBS Kit- HS 200 Cycle, Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). An average of 4.6M reads passing trimming and minimum count filter (≥ 5 reads) was generated per sample.

CASAVA software version 1.8.4 was used for de-multiplexing, removal of low quality reads, and production of FASTQ sequence files. The FASTX (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html) application was used to trim the 3’-end of sequence reads in order to remove the 3’ adaptor sequence. Sequences without any 3’ adapter sequence as well as sequences of less than 17 nucleotides after trimming were removed. A perl script was used to remove sequences with any amount of 5’ –adapter sequence. FASTX was also used to collapse identical reads into single entries retaining the read count for each unique sequence. Alignment results files were parsed by a custom perl script to generate FASTA files containing the read count and annotation for each unique sequence. An additional perl script was used to parse the annotated FASTA in order to determine the raw sequence read count for each target database entry in each sample; these counts were written to tabular format text files. To filter out any sequencing errors, only sequence reads that occurred ≥5 were retained for further analysis. Non-redundant sequences were then aligned to genomic (hg19) and mRNA sequence (hg19) using bowtie2 (27); sequences with perfect match and 1nt mismatch (to aid mapping) were retained for further analysis. The genome-mapped sequences were further aligned to precursor and mature microRNAs in miRBase 21.0 (28) using OMAP# alignment software developed at Ocean Ridge Biosciences. To facilitate statistical analysis, the raw reads were converted to reads per million (genome) mapped reads (RPM). Only sequences with perfect match were retained for statistical analysis. Mature microRNA RPM values were normalized using the following formula: raw count / perfectly matched microRNA reads X 1,000,000. Tables were filtered to retain a list of annotated RNAs having a minimum of 10 mapped reads (Detection Threshold) in 25% of samples; for these filtered read tables, missing values were replaced with the average RPM value equivalent to 1 read. Library packages are available on CRAN. PCA plot for microRNAs was done employing Qlucore Omics Explorer. MicroRNA clustering was done in R using kendall/ward.D method.

Polyribosome profiling

Polyribosome profiling was done as described previously (20, 22) with the addition of 500μg/mL cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) in the lysis buffer, in passage 1 BECs. Briefly, cytoplasmic extracts were spun at 8000rpm at 4°C in a minifuge. Supernatants were carefully removed and 10% was saved for cytoplasmic (Total) RNA extraction- the rest was carefully loaded onto sucrose gradients. Preparation of the gradients, reading of polyribosome profiles and extraction of individual polyribosome peaks were all done employing a Gradient Station (Biocomp Instruments, Canada) equipped with Bioprobes. Polyribosome profiles were generated reading the absorbance at 260nm of spun gradients immediately after ultracentrifugation. The 80S-to-polyribosome ratio is a signature of the translational status of cells and it is greatly modified when global translation is increased or impaired (29). We did not observe a difference in the translational profile between HCs and SA, as shown by similar ratios of monosome (80S) to polyribosome peaks (Supplemental Figure 1). Polysome excludes the monosomal fraction (80S) as this may contain mRNAs not undergoing translation or lowly expressed genes (29, 30). RNA was isolated from the individual polyribosomal peaks (as well as Total RNA) employing TRizol LS (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) following manufacturer’s instructions, pooled to constitute the Polysome fraction and sequenced.

RNA-sequencing

RNA quality was assessed using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent) with all sequenced samples showing a RIN value greater than 7 (RIN average +/- standard deviation =8.95 +/- 0.62). Libraries and sequencing were done in Expression Analysis Inc. (Durham, USA). Libraries were made using TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) and sequenced in a Hiseq 2500 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) platform (100bp, paired-end sequencing). A minimum of 14M reads/sample was generated. Upon completion of sequencing, base call files were converted into FASTQ files using Illumina Software (CASAVA). To prepare the reads for alignment, the sequencing adapters and other low quality bases were clipped. Reads were aligned to External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) sequences to assess the success of library construction and sequencing. A subset (~1M reads) was aligned to other spiked-in control sequences (PhiX and other Illumina controls used during library preparation), residual sequences (globin and ribosomal RNA), and poly-A/T sequences that persisted after clipping. The reads were also aligned to a sampling of intergenic regions to assess the level of DNA contamination. To determine the origin of all reads as a method of quality control, the unaligned reads were aligned to the full genome (not transcriptome) using BWA 0.6.2 (31). RSEM v1.2.0 was used to quantify and compute estimated counts by genes and transcripts (32) using the UCSC knownGene. All 77k isoforms defined by UCSC hg19 were considered as initial candidates. 12,485 isoforms are associated with only one gene, and thus were not considered further. Over 12k isoforms had 0 or nearly 0 counts for all subjects. Upper Quartile normalization was used to normalize between different samples with different read depths for both aggregate gene expression and isoform analysis. Each sample was scaled to that the Upper Quartile of counts was equal to 1000. Only genes and isoforms with median counts of 10 or more on each group (Total or Polysome) were taken into account. PROC-GLM was used to perform preliminary statistical analysis (code at https://gist.github.com/rociotmartinez/7284e38817fe3ba09aca515c4f845bdb). Clustering methods employed were: Pearson/mcquitty method in heatmaps for differentially expressed/bound genes and in heatmaps for differentially expressed/bound isoforms using Kendall/centroid method. Heatmaps and the generation of z-scores (which scales values according to mean and standard deviation) were done in R.

RT-qPCR and Splicing Assays

MicroRNA validations were performed using the miScript system (QIAGEN, Manchester, UK) following manufacturer’s instructions. MicroRNA expression was normalised against hsa-let-7a-5p.

RNA was reverse-transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Validations of differentially expressed genes and assays of microRNA effects were performed employing qPCRs using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific), using the primers with maximum coverage. Supplemental Figure 8 EGFR primers were kindly provided by N. Smithers and designed by Dr D. Smart (both at University of Southampton) and used as a SYBR Green assay (GoTaq qPCR Master Mix, Promega, UK). Primers employed in splicing assays were: ACBD4_FOR: TGAATGGAGATGTTGGGGCT; ACBD4_REV: TAGTGCTCGAACTGTCCCCA; IRAK3_FOR: CACACGCTGCTGTTCGAC; IRAK3_REV: TATATTTGGAAATCCACCTTCCTG; ITGA2_FOR: CTGGTGTTAGCGCTCAGTCA; ITGA2_REV: GTTCCTGGTGAGGATCAAGC; ITGA6_FOR: GTGTTTATACTATGGAAGTGTGG; ITGA6_REV: CGTTCCACTTTGTGATCCACT. Primers employed in Supplemental Figure 8 for EGFR detection were: EGFR FOR: GGAGAACTGCCAGAAACTGACC, EGFR REV: GCCTGCAGCACACTGGTTG.

Gene expression was normalised against GAPDH. Splicing was measured employing a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) and % spliced calculated as Included/(Included+Skipped).

Pathway Analysis

Data were analyzed using QIAGEN’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, QIAGEN, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity), employing genes/isoforms with a cut-off of P ≤ 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg P-adjusted ≤ 0.05, (33). Analysis with a cut-off P ≤ 0.01 missed important disease-related information. Grouping of pathways was done employing the IPA database and bibliography.

MicroRNA Analysis

MicroRNA :: target interaction was determined by cross-referencing the up regulated differentially expressed isoforms (as gene ID) with the down regulated microRNAs and vice versa employing TargetScan 7.1 (34). We increased the stringency by accounting only for isoform ratios (SA/HC) of more than 1.5 or less than 0.66. Importantly, when sliding the ratios to less than 0.5 or more than 2 as well as not adding any restrictions on ratios, our results relating to the mRNA expression cumulative distributions differences remained significant (Supplemental Figure 4). Interactive networks in Supplemental Interactive Figures 1 and 2 were done employing networkD3 package in R.

MicroRNA Transfections

MicroRNA transfections were performed using Interferin (Polyplus) following manufacturer’s instructions as in (7). Briefly, 16nM of each anti- or pre-microRNA were transfected into bronchial epithelial cells from healthy controls. 48h post-transfection, cells were pre-incubated or not with 10-7M dexamethasone during 2h and stimulated with 10ng/mL IL-1β (or vehicle). Cells were harvested 24h after stimulation and RNA extracted and analysed.

Image processing

Graphs for polyribosome profiles, validations, pathway analyses and microRNA analyses were produced using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 or v7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Heatmaps were produced using R statistical language, version 3.2.0 (R project for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org/) and their labels clarified in Adobe Illustrator CS5. All packages used in R are available in CRAN repository. All figures panels were put together using Adobe Illustrator CS5. Frequency distribution plots in Supplemental Figure 4 were done by adjusting the data to a non-linear regression to facilitate and clarify data presentation employing GraphPad Prism v6.07.

Statistical analysis

Clinical parameters statistics (except for sex and atopy) as well as statistical analyses of validations were done employing a Mann-Whitney U-test for non-parametric data and unpaired t-tests for parametric data comparisons, according to D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test. Differences in sex and atopy between HC and SA were tested employing a Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 or 7.

MicroRNAs shown in Supplemental Table 2 had a P ≤ 0.05 and a restricted fold change of less than 0.66 or more than 1.5 (SA/HC), which showed an FDR ≤ 0.05 when corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (33). For gene and isoform expression, a restrictive P ≤ 0.01 (two group t-test) was taken to perform the heatmaps. Nominal significant P values from RNA-seq datasets (two-group test, P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.05, Supplemental Datasets 1, 3, 5 and 7) were corrected by applying the Benjamini-Hochberg method (33) employing R, which showed an FDR ≤ 0.05 for all genes and isoforms displayed in the figures and used in pathway analysis. FDR was calculated also experimentally based on the gene expression assays (0.136), and was in the 0.1-0.2 range in accordance with previous studies (20, 35). The P value displayed in all pathway analyses was calculated in IPA employing a Fisher’s exact test.

Statistical analysis of proportions for microRNA targeting between Total and Polysome was done employing the Fisher’s exact test in GraphPad Prism version 6.07. Statistics comparing cumulative distributions in Supplemental Figure 4 were performed employing a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test as in (34) using GraphPad Prism v6.07.

The sequencing datasets used for analysis have been deposited and are publicly available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) as GSE85216, GSE85215 and GSE85214.

Results

Severe asthma bronchial epithelial cells present genome-wide differences in microRNA levels compared to healthy donors

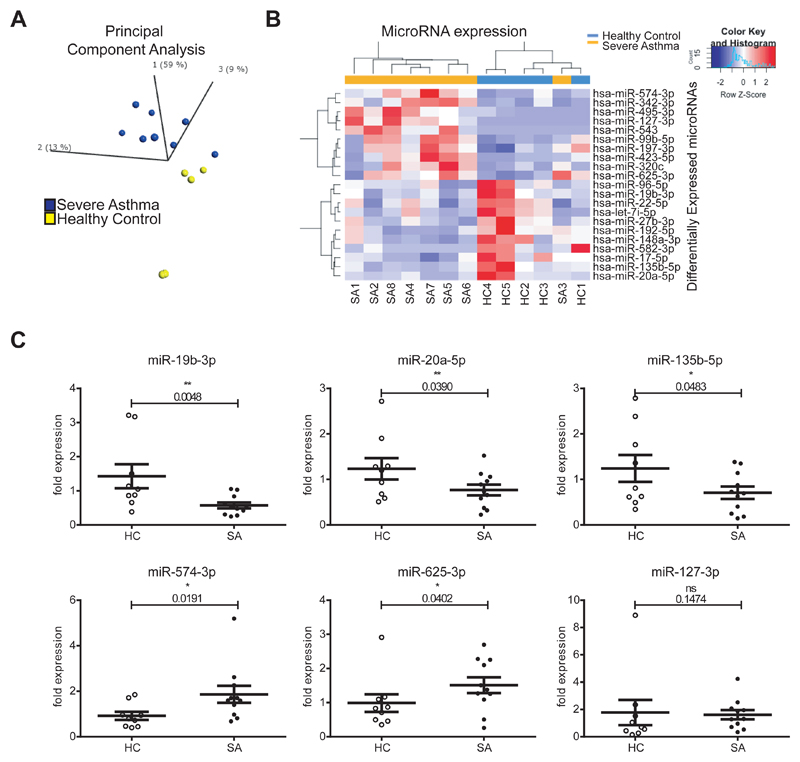

To determine microRNA expression we performed small RNA-sequencing on BECs (healthy controls, HC=5; severe asthmatics, SA=8). The demographics of the study population are in Supplemental Table 1, highlighting the main clinical characteristics that differed between healthy and severe asthmatics. Lung function and cellular profile of their bronchoalveolar lavage was found statistically significant between health and severe asthma, as expected. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, atopy or weight (BMI) between the two groups. Healthy controls had no history of respiratory disease or current symptoms and no evidence of abnormal bronchial reactivity on methacholine inhalation challenge testing. Severe asthma patients had inadequately controlled disease and fulfilled the ERS/ATS criteria for severe asthma. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (employing microRNAs with P < 0.05 between HC and SA, 0.66 > SA/HC ratio > 1.5, Supplemental Table 2) identified that widespread microRNA expression is different between HC and SA patients (Figure 1A). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of 21 differentially expressed microRNAs separated the samples between health and disease, with the exception of SA3 (Figure 1B). We validated these findings with microRNA RT-qPCRs on an expanded cohort (n=9 HC and n=11 SA, Figure 1C, most differentially expressed microRNAs). MicroRNAs -19b-3p, -20a-5p, 135b-5p, -574-3p and 625-3p were validated, while only miR-127-3p showed no significant differences between SA and HC amongst the candidates tested.

Figure 1. MicroRNAs are dysregulated in human severe asthma bronchial epithelium.

A: Principal Component Analysis plot showing the distribution of healthy (yellow) and severe asthma (blue) samples according to the levels of differentially expressed microRNAs (microRNAs with a P <0.05, 0.66 > SA/HC ratio > 1.5). B: Heatmap depicting unsupervised clustering of healthy controls and severe asthmatics based on the expression values of differentially expressed microRNAs (P < 0.05, 0.66 > SA/HC ratio > 1.5). C: Dot plots (mean + standard error of the mean) representing qPCR analysis of several microRNAs (n=9 HC, n=11 SA). Statistics were done employing t-tests. HC: Healthy control; SA: Severe Asthma. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis highlighted the impact of the remaining 20 dysregulated microRNAs on molecular and cellular functions of relevance to asthma (Supplemental Table 3), as well as association with Organismal Repair and Abnormalities (18 microRNAs), Inflammatory Response and Immunological Disease (9 microRNAs each). Thus, microRNAs dysregulated in SA may underlie important general pathological processes in asthma related to epithelial repair and inflammation via post-transcriptional mRNA regulation.

Total mRNA expression is altered in severe asthma bronchial epithelium

As microRNAs may regulate mRNA levels by destabilization (4, 24), we performed transcriptomics analysis by RNA-sequencing. Genome-wide mRNA expression analysis revealed 16,277 expressed genes in BECs (median read counts ≥ 10) with 194 Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs, P ≤ 0.01, Supplemental Dataset 1). Unsupervised cluster analysis of DEGs separated HC and SA samples (Figure 2A). RT-qPCRs (Figures 2B and Supplemental Figure 2) validated a decreased expression of COL21A1, CEBPA and CTSD mRNAs and an up-regulation of IGFL1, IL23A, ABCC4, PDPN and IL31RA gene expression in SA compared to HC on an expanded cohort (n=10 HC, n=11 SA).

Figure 2. Genome-wide mRNA expression is dysregulated in severe asthma.

A: Heatmap showing unsupervised clustering of Differentially Expressed Genes (P ≤ 0.01) in the Total fraction. B: Dot plots (mean + standard error of the mean) representing qPCRs validating the RNA-seq dataset (n=10 HC, n=11 SA). Statistics were done employing t-tests. C: Table showing 6 of the top 10 pathways predicted by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for differentially expressed genes. Statistics were done employing Fisher’s 2-tailed test. HC: Healthy Control; SA: Severe Asthmatics; DEGs: Differentially Expressed Genes. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

IPA identified dysregulated pathways attributable to the detected DEGs (Figure 2C, Supplemental Dataset 2). This revealed non-Type2 inflammatory pathways, as well as glucocorticoid activation- and drug metabolism-related pathways. The pathway with the strongest statistically significant dysregulation (P = 0.001) was PXR/RXR (Pregnane X Receptor/Retinoid X Receptor), related to endobiotic and xenobiotic/drug metabolism (36), consistent with the high dose corticosteroid therapy prescribed to the severe asthmatics (37). Dysregulated LPS/IL-1 Mediated Inhibition of RXR Function (P = 0.0055) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 Biosynthesis (P = 0.0049) were also evident.

Translation in severe asthma bronchial epithelium is altered at the genome-wide level

Frac-seq was performed to determine the levels of mRNAs undergoing translation in BECs (Figure 3A) in the same healthy individuals and severe asthma patients as in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 3B depicts two representative polyribosome profiles of both healthy controls and severe asthma patients (remaining in Supplemental Figure 1). The same mRNAs as previously detected (Figure 2) were evident in the Polysome fraction (16,277 genes, median read counts ≥ 10). Severe asthmatic patients and healthy donors differed in the binding to polyribosomes for 243 genes (DBGs, P ≤ 0.01, Supplemental Dataset 3). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of DBGs distinguished between HC and SA (Figure 3C). Noteworthy, severe asthma patients with earlier onset disease (onset <25 years old) clustered differently to the other five SA samples (onset >40 years old). Figures 3D and Supplemental Figure 3 show the results from the validations of several candidate genes on the expanded cohort employing qPCRs (n=10 HC, n=11 SA). This confirmed that IGFL1, IL23A, IL1A, PDPN, IL31RA, ABCC4 and LTB genes were all more bound to polyribosomes in SA than in HC. In contrast to total mRNA, there was no evidence of decreased polyribosomal binding of COL21A1 in severe asthma.

Figure 3. Genome-wide translation is dysregulated in severe asthma.

A: Schematic of Frac-seq experiment. RNA-seq was performed on total (Total) and polyribosome-bound (Polysome) mRNA; Total HC vs Total SA and Polysome HC vs Polysome SA datasets were then compared. B. Representative polyribosome profiles from healthy (left) and severe asthma (right) BECs. C: Heatmap showing unsupervised clustering of Differentially Bound Genes (P ≤ 0.01) in the Polysome fraction. D: Dot plots (mean + standard error of the mean) representing qPCRs validating the RNA-seq dataset (n=10 HC, n=11 SA). Statistics were done employing t-tests. E: Table showing 6 pathways predicted by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for differentially bound genes not found in the Total fraction. Statistics were done employing Fisher’s 2-tailed test. BECs: Bronchial Epithelial Cells; HC: Healthy Control; SA: Severe Asthmatics; DBGs: Differentially Bound Genes. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Pathway analysis was undertaken and dysregulated pathways clustered into the same categories as in Figure 2C (Supplemental Dataset 4, Figure 3E). Unlike DEGs in Total, DBGs in Polysome did not map to glucocorticoid or endobiotic metabolism. Pathways present in Polysome DBGs and absent in Total DEGs included Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (P = 0.04) and IL-1-related inflammation (P = 0.004), both implicated in severe asthma (38, 39), as well as phagosome formation (P = 0.025).

Together, these results identify that there is genome-wide dysregulation of translation (mRNAs bound to polyribosomes) in asthma, and that this impacts additional pathways and genes that differ from those detected when analyzing Total mRNA levels, suggestive of an underlying strong post-transcriptional signature.

Isoform mRNA analysis reveals structural and inflammatory anomalies in severe asthma bronchial epithelium not disclosed by aggregate gene expression

Alternative splicing analysis of the RNA-seq data revealed 30,831 mRNAs (median counts ≥ 10) in both Total and Polysome fractions. Differential Expression analysis of Isoforms (DEIs, P ≤ 0.01, Supplemental Dataset 5) revealed 319 mRNA isoforms differentially expressed between HC and SA in Total. Unsupervised clustering of DEIs clearly distinguished healthy and severe asthma samples (Figure 4A), indicating that the bronchial epithelial expression of alternatively spliced mRNAs is different globally between HC and SA.

Figure 4. Genome-wide mRNA alternative splicing is dysregulated in severe asthma and adds novel information to that detected by gene expression analysis.

A: Heatmap showing unsupervised clustering of donors according to differentially expressed isoforms (P ≤ 0.01) in the total fraction between HC and SA. B: Dot plots (mean + standard error of the mean) representing the RT-PCR splicing assays for IRAK3 and ACBD4 skipped isoforms (HC n=5, SA n=8, left column) and their corresponding qPCR assay for aggregate gene expression (HC n=6, SA n=8, right column). RT-PCRs were quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA microfluidic chip and % splicing calculated and plotted as %inclusion= [included isoform]/([included isoform]+[excluded isoform]). Statistics were done employing t-tests. C: Table showing 6 pathways predicted by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for differentially expressed isoforms in the Total fraction. Statistics were done employing Fisher’s 2-tailed test. DEIs: Differentially Expressed Isoforms; HC: Healthy Control; SA: Severe Asthmatics; ns: non-significant. * P < 0.05.

The differentially expressed isoforms mapped to genes that were detected as differentially expressed in Total genes (Figure 2, overlap of ~32% DEIs gene IDs in DEGs at P < 0.01), although alternative splicing analysis also revealed new candidates validated employing splicing assays. Figure 4B depicts the results: left column shows the results from alternative splicing assays (RT-PCRs quantified using a Bioanalyzer) and right column those of aggregate gene expression (=all isoforms, measured by qPCRs). The skipped isoform of IRAK3 (Interleukin-1 Receptor-Associated Kinase 3) was increased in severe asthma BECs, but was not detected differentially expressed employing aggregate gene expression assay. On the other hand, aggregate gene expression analysis detected ACBD4 as down regulated in severe asthma while alternative splicing analysis revealed no difference. Thus, alternative splicing analysis reveals novel candidates related to asthma biology involved in inflammatory functions of bronchial epithelium not disclosed by aggregate gene expression analysis.

Differentially expressed isoforms were mapped onto pathways using IPA and grouped similarly to Figures 2 and 3 with the addition of epithelial repair/remodeling pathways (Supplemental Dataset 6), which became apparent when performing alternative splicing analysis. Figure 4C shows 6 pathways amongst the top 10 according to P value. Consistently with our previous findings in Total differentially expressed genes (Figure 2C), Total differentially expressed isoforms affected glucocorticoid signalling (P = 0.0044), but analysis of isoforms detected new pathways including IL-6-JAK/STAT signalling (P = 0.004).

To interrogate the impact of alternative splicing on mRNA translation we also analyzed alternatively spliced isoforms on polyribosome-bound mRNAs. This identified 335 mRNA isoforms differentially bound to polyribosomes (DBIs) between HC and SA (Supplemental Dataset 7) that allowed unsupervised clustering of the samples (Figure 5A). Several candidates in the Polysome fraction were validated by splicing assays and possible differences with aggregate gene expression (overlap of ~37% DBIs gene IDs in DBGs at P < 0.01) assessed using qPCRs (Figure 5B). The skipped isoforms of ITGA2 and ITGA6 genes presented increased polyribosome binding in severe asthma, information missed when performing gene expression analysis. ITGA6 and ITGA2 encode for integrins, key structural proteins in cell adhesion and signaling (40). IRAK3 skipped isoform (increased only in Total DEIs, Figure 4C) showed increased binding to polyribosomes when performing analysis of aggregate gene expression.

Figure 5. Genome-wide binding of mRNA isoforms to polyribosomes is dysregulated in severe asthma providing novel information to that detected by gene expression analysis.

A: Heatmap showing unsupervised clustering of donors according to differentially bound isoforms (P ≤ 0.01) in the Polysome fraction between HC and SA. B: Dot plots (mean + standard error of the mean) representing the RT-PCR splicing assays for ITGA2, ITGA6 and IRAK3 skipped isoforms (HC n=5, SA n=8, left column) and their corresponding qPCR results for aggregate gene expression (HC n=6, SA n=8, right column). RT-PCRs were quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA microfluidic chip and % splicing calculated and plotted as %inclusion= [included isoform]/([included isoform]+[excluded isoform]). Statistics were done employing t-tests. C: Table showing 6 pathways predicted by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for differentially bound isoforms not found in the Total fraction. Statistics were done employing Fisher’s 2-tailed tests. DBIs: Differentially Bound Isoforms; HC: Healthy Control; SA: Severe Asthmatics; ns: non-significant. * P < 0.05.

IPA of Polysome differentially bound isoforms revealed down-regulation of Notch signaling (Figure 5C and Supplemental Dataset 8), suggesting a decreased airway Type2-response (41) in severe asthma. Differentially bound isoforms in Polysome determined dysregulation of telomere extension, with telomere length in leukocytes previously related to asthma (42). Polysome DBIs also revealed pathways relating to epithelial cell repair/remodeling (e.g. Calpain protease or Paxillin signaling), consistent with the airways epithelium impairment observed in asthma (43).

Together, these data show that alternative splicing is dysregulated in severe asthma bronchial epithelium at a global scale affecting the translation of mRNAs encoding structural and inflammatory factors.

MicroRNAs associate with genome-wide changes in mRNA expression at the transcriptional and translational levels

To determine the genome-wide effect of microRNAs dysregulated in the bronchial epithelium of asthma patients we aimed to identify which differentially expressed mRNAs were targeted by microRNAs on each fraction. To do so, we cross-referenced the predicted targets from TargetScan 7.1 (34) for the 20 microRNAs (Figure 1, all except for miR-127-3p) with the differentially expressed isoforms in Total and Polysome (Figures 4 and 5), as microRNAs are known to target specific isoforms (44). This showed that microRNAs significantly modify the levels of both cytoplasmic and translating mRNAs (Supplemental Figure 4). The overlap between targets in the cytoplasmic and polyribosome bound mRNA fractions was very low (Figure 6A, 11.2 % of Total DEIs and 7.6 % of Polysome DBIs), suggesting that microRNAs dysregulated in asthma may have different effects depending on the mechanism of action (mRNA degradation or blocking of translation). MicroRNAs showed preferential targeting of polyribosome-bound mRNAs (172/288) compared to cytoplasmic mRNAs (116/231) (Supplemental Figure 5A, 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test P = 0.0331) consistent with mRNAs presenting more or less MREs according to their association with polyribosomes (Supplemental Figure 5B and (20)). These results suggest that dysregulated microRNAs in asthma may have more impact in protein translation than on mRNA levels.

Figure 6. A subset of 6 microRNAs controls most of the mRNA targeting in severe asthma bronchial epithelium.

A: Venn diagram depicting the overlap between total and polyribosome-bound microRNA targets by cross-referencing differentially expressed/bound isoforms with differentially expressed microRNAs in severe asthma. B: Bar plot depicting the number of targets for each differentially expressed microRNA in the total (yellow) and polyribosome bound (magenta) fractions. Highlighted in red are microRNAs with most abundant sites. C: Dot plots (mean + standard error of the mean) representing qPCRs validating the subset of microRNAs amongst those with the highest number of targets in both fractions (n=11 HC, n=11 SA). Statistics were done employing t-tests. D: Bar plot depicting the proportional abundance of targets for the 6 validated microRNAs in total (yellow) and polyribosome bound (magenta) fractions. Polyribosome bound mRNAs have a higher abundance of microRNA targets (2-tailed Fisher’s exact test). E: Pie chart depicting the proportion of targets amongst mRNAs controlled by microRNAs in the polyribosome bound fraction that is potentially regulated by the validated 6 microRNAs. F: Table showing the main asthma-related pathways predicted by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for mRNA isoforms differentially bound to polyribosomes and potentially targeted by the hub of 6 microRNAs. Red: up-regulated; blue: down-regulated. Statistics were done employing Fisher’s 2-tailed test. G, H, I: Bar plots showing the results from transfecting the hub of 6 microRNAs (MiR MiX) compared to pre-microRNA and anti-microRNA controls at equimolar concentrations onto BECs from healthy controls. 48h post-transfection cells were pre-treated or not during 2h with dexamethasone, stimulated or not with IL-1β and harvested 24h later. BECs: Bronchial Epithelial Cells; HC: Healthy Control; SA: Severe Asthmatics; CmiR: control pre- and anti-microRNA mixture, MiR MiX: microRNA hub; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

The relevance of each one of the 20 microRNAs in targeting Total and Polysome mRNAs was then evaluated. Figure 6B shows the number of targets per microRNA, which revealed that a group of only 8 microRNAs controls most of the mRNA changes detected in severe asthma both at cytoplasmic and polyribosome binding levels. Amongst those 8 microRNAs, dysregulated expression of 6 microRNAs was validated in our larger cohort of patients (n=11 for each group, Figures 6C and Supplemental Figure 6). These 6 microRNAs were also predicted to preferentially modulate changes on translating mRNAs (48.2% as opposed to 35.9% in Total, Figure 6D, P = 0.0056). Network analyses of microRNA :: target interactions showed that the target mRNAs of these 6 microRNAs are in many cases co-regulated by multiple microRNAs. This suggests that the expression of these mRNAs is tightly controlled, but disrupted in severe asthma patients (interactive networks in Supplemental Interactive Figures 1 and 2, data in Supplemental Datasets 9 and 10). Strikingly, this network of 6 microRNAs was predicted to control almost 90% of all targeted mRNAs in the Polysome fraction (Figure 6E), which mapped to inositol pathways and cell cycle (Figure 6F, Supplemental Table 4) the latter desynchronized in asthma (45).

In order to validate our findings, we transfected BECs from healthy donors with the microRNA network to evaluate the effects of the dysregulated microRNA hub found in severe asthma BECs. Namely, anti-miR-22-5p, anti-miR-148a-3p, pre-miR-342-3p, pre-miR-495-3p, pre-miR-543 and pre-miR-197-3p oligonucleotides were co-transfected at equimolar concentrations and compared to BECs co-transfected with negative anti-microRNA and pre-microRNA controls at equimolar concentrations. Cells were then treated with IL-1β, which is found up-regulated in SA (and highlighted in our pathway analysis) as well as assessed for glucocorticoid sensitivity. Figures 6G-I show that the microRNA network was able to ablate the inhibition by glucocorticoids of IL-1β driven IL-6 mRNA expression (Figure 6I). The microRNA hub was also able to up-regulate TGFBR2 mRNA expression (Figure 6H) as well as significantly increase IL-1β- driven TNF mRNA expression. These are all characteristics well defined in severe asthma patients, highlighting the biological importance of microRNA dysregulation in severe asthma bronchial epithelium.

Integrated together, our data demonstrate that there is widespread deregulation of post-transcriptional processes in human asthma. Our work shows that the dysregulation of a microRNA hub causes genome-wide dysfunction in the translation of mRNAs encoding structural and inflammatory factors in the bronchial epithelium of severe asthma patients, and demonstrates the value of integrating multiple –omics datasets when investigating human biological processes.

Discussion

Our work integrating Frac-seq and small RNA-seq reveals that microRNAs, cytoplasmic mRNAs and translating mRNAs are all dysregulated in human primary airway cells from asthma patients. Integrating differentially expressed microRNAs and mRNAs determines that altered microRNA expression impacts on the detected mRNA changes, underlying abnormalities relating to inflammation, glucocorticoid sensitivity and epithelial repair detected by pathway analysis. This is effected through genome-wide modulation of mRNA levels and most predominantly through regulation of mRNA binding to polyribosomes. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to employ polyribosome profiling in human clinical samples and demonstrates that this approach reveals disease pathways and mRNA candidates not disclosed by other approaches, mainly transcriptomics, widely employed when studying human disease. For example, severe asthma patients with an earlier disease onset clustered differently than those with later onset (Figure 3) in the Polysome fraction. Although more numbers are needed to confirm this observation, it is consistent with reports suggesting that early and late onset SA represent stratified types of asthma with different etiologies (46). Polyribosome bound mRNA analysis therefore highlights disease-related information overseen by Total mRNA measurements and may serve as a novel tool to endotype patients, key into understanding and managing patients with complex diseases such as asthma and one of the hallmarks of personalized medicine.

One of the key advantages of Frac-seq is that it has more coverage (i.e. number of molecules revealed) than current proteomics approaches and informs about underlying molecular mechanisms of mRNA regulation, revealing mRNA isoforms preferentially bound to polyribosomes (20). Additionally, it reveals alternative splicing events that may lead to changes in 3’UTRs or 5’UTRs, which may not render differences in the aminoacid sequence of proteins but strongly impact on mRNA translation regulation. Expression changes in mRNAs undergoing translation revealed pathway abnormalities in severe asthma relating to Toll-like receptor signaling, the IL-1 pathway and to p38 MAPK. Importantly, IL1A was detected as differentially translated and not transcribed (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure 2, respectively). These are all pathways distinct from those related to classical type 2 inflammation described in untreated steroid-responsive asthma (47) and mostly absent in our cohort (Supplemental Figure 7). Moreover, the dysregulated microRNA network was found to regulate IL-1β responses in BECs (Figure 6G and 6I), highlighting the intricate post-transcriptional dysregulation underlying disease characteristics in severe asthma BECs.

Recent studies suggest that all human genes undergo alternative splicing (AS) producing at least two alternative mRNA isoforms (19), with around 80% of AS events estimated to lead to protein modifications (48) and AS influencing protein output (21). Moreover, 25% disease-related mutations have been linked to defects in splicing (49). If such changes existed in asthma, they could have profound and genome-wide implications in the proteins expressed by cells and thus in cellular function (21). The more in depth analysis of mRNA isoforms differentially bound to polyribosomes identified, amongst other findings, defective signaling related to epithelial repair/remodeling pathways (e.g. Calpain protease or Paxillin signaling), supporting evidence from other approaches that there is an altered epithelial repair phenotype in severe asthma (10, 50). These results are also supported by increased binding to polyribosomes of ITGA2 and ITGA6 mRNA isoforms in severe asthma (Figure 5), integrins being key adhesion and signaling proteins in the barrier (40).

The relevance and implications of employing Frac-seq in human clinical samples are also supported by previous findings at the protein level. The identification of increased epithelial polyribosomal EGFR mRNA binding in severe asthma (Supplemental Figure 8) supports the reported increased epithelial expression of EGFR protein (51). This has been attributed to a repair phenotype promoted by TGFβ-induced cell cycle inhibition (52). The present finding of increased binding to polyribosomes of TGFBR2 (Supplemental Figure 8), the main epithelial receptor for TGFβ, regulated by the microRNA hub (Figure 6H), would underlie this potential. Bacterial products induce inflammatory responses via EGFR and TLR- mediated pathways (53), with TLR-signaling present in pathways altered in Polysome, and viruses and bacteria exploiting EGFR to facilitate their survival (54, 55) or to attenuate the host response (56). Increased IL23A, IL31R and IL1A translation in the epithelium would be consistent with an immune system orientated towards Type I and type 17 directed inflammation (Supplemental Figure 7), more characteristic of a bacterial driven process, as would be the Toll receptor pathway activation, phagosome formation and the evidence of altered IL6 isoforms binding to polyribosomes as well as IL-6 signaling in DBIs (Supplemental Datasets 7 and 8).

The translation of genes linked to innate immune responses raises the possibility that they arise in response to the altered airway microbiome in severe asthma (57). An altered airway microbiome may also contribute to steroid resistance, one of the features of severe asthma. Patients with severe asthma suffer from persistent disease despite use of maximum therapy, including high dose of glucocorticoids. In the present study, glucocorticoid signaling was detected in Total (Supplemental Datasets 2 and 6), suggesting that corticosteroids are effectively reaching the airways of these patients and indicating that the lack of effect of steroid treatment is not a reflection of lack of adherence to treatment. Consideration needs to be given as to whether some of the differential expression changes in severe asthma reflect steroid treatment. This does not appear the case for microRNAs as previous in vivo studies have reported that glucocorticoids have little effect on microRNA expression in bronchial epithelium (58, 59). Whilst steroids affect mRNA expression, there was no overlap between the identified up-regulated differentially expressed genes in Total or Polysome and gene changes described from previous genome-wide studies aimed at determining the effect of corticoids on gene expression (60, 61). Thus the majority of described differential gene changes are likely to reflect alterations related to the underlying disease pathophysiology rather than directly due to their current therapy. Whilst glucocorticoid signaling was evident in Total, no glucocorticoid signaling was detectable in the polyribosome associated pathways. DUSP1 was identified as down-regulated in SA, whilst several studies have highlighted the importance of this in glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory effects (62, 63). Indeed, we found that the microRNA network ablated the inhibition by glucocorticoids of IL-1β- driven IL-6 mRNA expression (Figure 6G), potentially mimicking SA insensitivity to corticosteroids. IL-6 and IL-8 are typical inflammatory cytokines that are expressed by BECs and inhibited by glucocorticoids (64), and are up-regulated in the airways of patients with severe asthma (65). We also tested IL-8 mRNA expression, which showed a similar pattern but non-statistically significant (data not shown). Thus, in severe asthma there are non-steroid responsive pathways evident within the bronchial epithelium mRNA translational signature, and regulated by the hub of 6 microRNAs. These results may relate with the reported studies showing microRNAs not being affected by corticosteroid treatment and our results showing their preferential role in translation in asthma (Figure 6). Together these data highlight the need for the development of additional or alternative approaches to therapy in these patients and the importance of using of polyribosome profiling to reveal novel pathophysiological mechanisms, of potential implications in other inflammatory diseases as previously implied in cancer (66).

Integrating small RNA expression allowed us to associate changes between mRNA and microRNA levels. Whilst previous studies have demonstrated the relevance of individual microRNAs in disease and particularly in asthma (67–69), there are no genome-wide studies addressing the relationship of microRNA levels with cytoplasmic and translational mRNA changes in asthma, and to our knowledge, in any other disease employing human clinical samples. Our results show that microRNA effects mostly rely on a hub of six microRNAs that potentially regulates ~ 50% of all dysregulated mRNAs undergoing translation and ~35% of cytoplasmic mRNA changes detected in asthma patients. We considered 6- 7- and 8-mer MREs, consistent with previous studies showing that all these contribute to target abundance (70). Our results are also consequent with microRNAs affecting both mRNA degradation (4, 24) and translation inhibition (2, 5). Recent work showing the relevance of ribosome binding for microRNA action (5), as well as mRNA degradation happening co-translationally (71) support our observation that microRNAs preferentially modulate mRNAs bound to polyribosomes. We could not find a relationship between the number of mRNA targets and the expression levels of the dysregulated microRNAs, as previously noted by (66) in neuroblastoma. MiR-148a-3p, with the highest expression in healthy, and miR-197-3p, with the highest expression in asthma, had the fewest number of mRNA targets amongst the hub of six microRNAs. Our results add novelty on a broad spectrum of biological contexts, as we have considered physiological changes in microRNA and mRNA levels in disease, rather than studying the isolated behavior of individual microRNAs or target mRNAs. In this context, microRNAs seem to target different mRNA populations when analyzing cytoplasmic or polyribosome-bound mRNAs (Figure 6). We cannot exclude the possibility that inhibition of translation may have precluded cytoplasmic changes due to decay (4), or indeed, that some of the up-regulation observed for microRNA targets may be due not only to a release of inhibition from microRNAs down-regulated but also to transcriptional activation. Our data was obtained at one given time for both cytoplasmic and polyribosomal compartments together with the cytoplasmic microRNAome, considering mRNA physiological levels, and supporting a preferential role for microRNAs in regulating mRNA translation and driving a disease phenotype in BECs (Figure 6). Our validations place these microRNAs as key players in regulating severe asthma characteristics, such as steroid refractoriness and inflammation. This is likely due to targeting of multiple signaling molecules in these pathways at the level of mRNA translation, such as DUSP1. Our results add to the latest studies demonstrating the intricate relationship between ribosome binding and mRNA fate with regards to stability and microRNA action.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that whilst translation and alternative splicing are well-controlled processes in health they are genome-wide dysregulated in asthma patients, and that microRNAs account for many of the observed mRNA changes. This study reveals a new role for microRNAs in controlling impaired translation in asthma of potential implications in other inflammatory-related diseases, placing a hub of six microRNAs as potential future therapeutic candidates to address steroid unresponsive epithelial activation in asthma. Our approach demonstrates the feasibility and added value of studying post-transcriptional gene regulation when investigating human biology and disease.

Supplementary Material

Network of interactions between the 6 microRNAs and their targets (gene ID of the isoforms) in the Total cytoplasmic fraction. Note the 2 subnetworks corresponding to microRNAs up-regulated and their down-regulated targets and vice versa (HTML).

Network of interactions between the 6 microRNAs and their targets (gene ID of the isoforms) in polyribosome bound mRNAs. Note the 2 subnetworks corresponding to microRNAs up-regulated and their down-regulated targets and vice versa. The 2 subnetworks are connected via GFOD1, since this gene presents 2 differentially expressed isoforms (one up-regulated and one down-regulated) that share the same 3′UTR (HTML).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the asthmatic and healthy participants who voluntarily participated in the research and thank the nursing support from the Southampton NIHR Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit and Southampton Centre for Biomedical Research (SCBR) that enabled the study. The authors thank Prof Mariana Castells, Dr Christopher Woelk, Dr Yawwani P Gunawardana, Dr Jeremy R Sanford, Dr Aishwarya Griselda Jacob and Dr Michael Breen for critical input to the manuscript. The authors thank Dr Michael Breen for statistical and computational analysis advice and Dr Jeongmin Woo for advice in R. The authors thank Dr Michael Edwards for his help with the experiments to test microRNA effects.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Medical Research Council UK [grant numbers G0800649 Wessex Severe Asthma Cohort, MR/K001035/1, G0900453]. Equipment (PHH and TSE) and reagents (RTMN) grants from Southampton Asthma, Allergy and Inflammation Research (AAIR) Charity. RTMN was in receipt of Post-doctoral Career track award from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton.

Abbreviations: BEC: bronchial epithelial cell; Frac-seq: subcellular fractionation and RNA-sequencing; HC: healthy control; Polysome: polyribosome; SA: severe asthma.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Prof Howarth reports personal fees from GSK, outside the submitted work.

The sequencing datasets used for analysis have been deposited and are publicly available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) as GSE85216, GSE85215 and GSE85214.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazzini AA, Lee MT, Giraldez AJ. Ribosome profiling shows that miR-430 reduces translation before causing mRNA decay in zebrafish. Science. 2012;336:233–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1215704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R. miRNA-mediated gene silencing by translational repression followed by mRNA deadenylation and decay. Science. 2012;336:237–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1215691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichhorn SW, Guo H, McGeary SE, Rodriguez-Mias RA, Shin C, Baek D, Hsu SH, Ghoshal K, Villen J, Bartel DP. mRNA destabilization is the dominant effect of mammalian microRNAs by the time substantial repression ensues. Mol Cell. 2014;56:104–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tat TT, Maroney PA, Chamnongpol S, Coller J, Nilsen TW. Cotranslational microRNA mediated messenger RNA destabilization. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:203–222. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Nunez RT, Bondanese VP, Louafi F, Francisco-Garcia AS, Rupani H, Bedke N, Holgate S, Howarth PH, Davies DE, Sanchez-Elsner T. A microRNA network dysregulated in asthma controls IL-6 production in bronchial epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunez-Iglesias J, Liu CC, Morgan TE, Finch CE, Zhou XJ. Joint genome-wide profiling of miRNA and mRNA expression in Alzheimer's disease cortex reveals altered miRNA regulation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, Boulet LP, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:343–73. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holgate ST, Roberts G, Arshad HS, Howarth PH, Davies DE. The role of the airway epithelium and its interaction with environmental factors in asthma pathogenesis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:655–9. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-072DP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. The airway epithelium in asthma. Nat Med. 2012;18:684–92. doi: 10.1038/nm.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piccirillo CA, Bjur E, Topisirovic I, Sonenberg N, Larsson O. Translational control of immune responses: from transcripts to translatomes. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:503–11. doi: 10.1038/ni.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsson O, Tian B, Sonenberg N. Toward a genome-wide landscape of translational control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a012302. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gygi SP, Rochon Y, Franza BR, Aebersold R. Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1720–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunawardana Y, Fujiwara S, Takeda A, Woo J, Woelk C, Niranjan M. Outlier detection at the transcriptome-proteome interface. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2530–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunawardana Y, Niranjan M. Bridging the gap between transcriptome and proteome measurements identifies post-translationally regulated genes. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:3060–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarai Y, Margaliot M, Tuller T. On the Ribosomal Density that Maximizes Protein Translation Rate. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:227–32. doi: 10.1038/nrg3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y, Rio DC. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:291–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterne-Weiler T, Martinez-Nunez RT, Howard JM, Cvitovik I, Katzman S, Tariq MA, Pourmand N, Sanford JR. Frac-seq reveals isoform-specific recruitment to polyribosomes. Genome Res. 2013;23:1615–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.148585.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floor SN, Doudna JA. Tunable protein synthesis by transcript isoforms in human cells. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Nunez RT, Sanford JR. Studying Isoform-Specific mRNA Recruitment to Polyribosomes with Frac-seq. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1358:99–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3067-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filipowicz W, Sonenberg N. The long unfinished march towards understanding microRNA-mediated repression. RNA. 2015;21:519–24. doi: 10.1261/rna.051219.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–40. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grainge CL, Lau LC, Ward JA, Dulay V, Lahiff G, Wilson S, Holgate S, Davies DE, Howarth PH. Effect of bronchoconstriction on airway remodeling in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2006–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowley C, Klanrit P, Butler CR, Varanou A, Plate M, Hynds RE, Chambers RC, Seifalian AM, Birchall MA, Janes SM. Surface modification of a POSS-nanocomposite material to enhance cellular integration of a synthetic bioscaffold. Biomaterials. 2016;83:283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D68–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingolia NT. Ribosome profiling: new views of translation, from single codons to genome scale. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:205–13. doi: 10.1038/nrg3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heyer EE, Moore MJ. Redefining the Translational Status of 80S Monosomes. Cell. 2016;164:757–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Querec TD, Akondy RS, Lee EK, Cao W, Nakaya HI, Teuwen D, Pirani A, Gernert K, Deng J, Marzolf B, Kennedy K, et al. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:116–25. doi: 10.1038/ni.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willson TM, Kliewer SA. PXR, CAR and drug metabolism. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:259–66. doi: 10.1038/nrd753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pascussi JM, Drocourt L, Fabre JM, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ. Dexamethasone induces pregnane X receptor and retinoid X receptor-alpha expression in human hepatocytes: synergistic increase of CYP3A4 induction by pregnane X receptor activators. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:361–72. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bezemer GF, Sagar S, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Georgiou NA, Garssen J, Kraneveld AD, Folkerts G. Dual role of Toll-like receptors in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:337–58. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao P, Gibson PG, Baines KJ, Yang IA, Upham JW, Reynolds PN, Hodge S, James AL, Jenkins C, Peters MJ, Zhang J, et al. Anti-inflammatory deficiencies in neutrophilic asthma: reduced galectin-3 and IL-1RA/IL-1beta. Respir Res. 2015;16:5. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0163-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harburger DS, Calderwood DA. Integrin signalling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:159–63. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park CS. Eosinophilic bronchitis, eosinophilia associated genetic variants, and notch signaling in asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:188–94. doi: 10.4168/aair.2010.2.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albrecht E, Sillanpaa E, Karrasch S, Alves AC, Codd V, Hovatta I, Buxton JL, Nelson CP, Broer L, Hagg S, Mangino M, et al. Telomere length in circulating leukocytes is associated with lung function and disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:983–92. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00046213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Muhsen S, Johnson JR, Hamid Q. Remodeling in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:451–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.047. quiz 463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandberg R, Neilson JR, Sarma A, Sharp PA, Burge CB. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3' untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science. 2008;320:1643–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1155390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freishtat RJ, Watson AM, Benton AS, Iqbal SF, Pillai DK, Rose MC, Hoffman EP. Asthmatic airway epithelium is intrinsically inflammatory and mitotically dyssynchronous. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:863–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0029OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, Green RH. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:218–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodruff PG, Boushey HA, Dolganov GM, Barker CS, Yang YH, Donnelly S, Ellwanger A, Sidhu SS, Dao-Pick TP, Pantoja C, Erle DJ, et al. Genome-wide profiling identifies epithelial cell genes associated with asthma and with treatment response to corticosteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15858–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707413104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Modrek B, Lee C. A genomic view of alternative splicing. Nat Genet. 2002;30:13–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0102-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sterne-Weiler T, Howard J, Mort M, Cooper DN, Sanford JR. Loss of exon identity is a common mechanism of human inherited disease. Genome Res. 2011;21:1563–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.118638.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loxham M, Davies DE, Blume C. Epithelial function and dysfunction in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:1299–313. doi: 10.1111/cea.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Puddicombe SM, Polosa R, Richter A, Krishna MT, Howarth PH, Holgate ST, Davies DE. Involvement of the epidermal growth factor receptor in epithelial repair in asthma. FASEB J. 2000;14:1362–74. doi: 10.1096/fj.14.10.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puddicombe SM, Torres-Lozano C, Richter A, Bucchieri F, Lordan JL, Howarth PH, Vrugt B, Albers R, Djukanovic R, Holgate ST, Wilson SJ, et al. Increased expression of p21(waf) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor in asthmatic bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:61–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koff JL, Shao MX, Ueki IF, Nadel JA. Multiple TLRs activate EGFR via a signaling cascade to produce innate immune responses in airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L1068–75. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Monick MM, Cameron K, Staber J, Powers LS, Yarovinsky TO, Koland JG, Hunninghake GW. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by respiratory syncytial virus results in increased inflammation and delayed apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2147–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Subauste MC, Proud D. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha on interleukin-8 production by, and human rhinovirus replication in, bronchial epithelial cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1229–34. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mikami F, Gu H, Jono H, Andalibi A, Kai H, Li JD. Epidermal growth factor receptor acts as a negative regulator for bacterium nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-induced Toll-like receptor 2 expression via an Src-dependent p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36185–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green BJ, Wiriyachaiporn S, Grainge C, Rogers GB, Kehagia V, Lau L, Carroll MP, Bruce KD, Howarth PH. Potentially pathogenic airway bacteria and neutrophilic inflammation in treatment resistant severe asthma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moschos SA, Williams AE, Perry MM, Birrell MA, Belvisi MG, Lindsay MA. Expression profiling in vivo demonstrates rapid changes in lung microRNA levels following lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation but not in the anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:240. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solberg OD, Ostrin EJ, Love MI, Peng JC, Bhakta NR, Hou L, Nguyen C, Solon M, Nguyen C, Barczak AJ, Zlock LT, et al. Airway epithelial miRNA expression is altered in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:965–74. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0027OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reddy TE, Pauli F, Sprouse RO, Neff NF, Newberry KM, Garabedian MJ, Myers RM. Genomic determination of the glucocorticoid response reveals unexpected mechanisms of gene regulation. Genome Res. 2009;19:2163–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.097022.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yick CY, Zwinderman AH, Kunst PW, Grunberg K, Mauad T, Fluiter K, Bel EH, Lutter R, Baas F, Sterk PJ. Glucocorticoid-induced changes in gene expression of airway smooth muscle in patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:1076–84. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1886OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abraham SM, Lawrence T, Kleiman A, Warden P, Medghalchi M, Tuckermann J, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Antiinflammatory effects of dexamethasone are partly dependent on induction of dual specificity phosphatase 1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1883–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin Y, Hu D, Peterson EL, Eng C, Levin AM, Wells K, Beckman K, Kumar R, Seibold MA, Karungi G, Zoratti A, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 1 as a pharmacogenetic modifier of inhaled steroid response among asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:618–25 e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levine SJ, Larivee P, Logun C, Angus CW, Shelhamer JH. Corticosteroids differentially regulate secretion of IL-6, IL-8, and G-CSF by a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:L360–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.265.4.L360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morjaria JB, Babu KS, Vijayanand P, Chauhan AJ, Davies DE, Holgate ST. Sputum IL-6 concentrations in severe asthma and its relationship with FEV1. Thorax. 2011;66:537. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.136523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dassi E, Greco V, Sidarovich V, Zuccotti P, Arseni N, Scaruffi P, Tonini GP, Quattrone A. Translational compensation of genomic instability in neuroblastoma. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14364. doi: 10.1038/srep14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haj-Salem I, Fakhfakh R, Berube JC, Jacques E, Plante S, Simard MJ, Bosse Y, Chakir J. MicroRNA-19a enhances proliferation of bronchial epithelial cells by targeting TGFbetaR2 gene in severe asthma. Allergy. 2015;70:212–9. doi: 10.1111/all.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim RY, Horvat JC, Pinkerton JW, Starkey MR, Essilfie AT, Mayall JR, Nair PM, Hansbro NG, Jones B, Haw TJ, Sunkara KP, et al. MicroRNA-21 drives severe, steroid-insensitive experimental asthma by amplifying phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mediated suppression of histone deacetylase 2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;2:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maes T, Cobos FA, Schleich F, Sorbello V, Henket M, De Preter K, Bracke KR, Conickx G, Mesnil C, Vandesompele J, Lahousse L, et al. Asthma inflammatory phenotypes show differential microRNA expression in sputum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1433–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Denzler R, McGeary SE, Title AC, Agarwal V, Bartel DP, Stoffel M. Impact of MicroRNA Levels, Target-Site Complementarity, and Cooperativity on Competing Endogenous RNA-Regulated Gene Expression. Mol Cell. 2016;64:565–579. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pelechano V, Wei W, Steinmetz LM. Widespread Co-translational RNA Decay Reveals Ribosome Dynamics. Cell. 2015;161:1400–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aich J, Mabalirajan U, Ahmad T, Agrawal A, Ghosh B. Loss-of-function of inositol polyphosphate-4-phosphatase reversibly increases the severity of allergic airway inflammation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:877. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gauthier M, Oriss T, Raundhal M, Morse C, Wenzel SE, Ray P, Ray A. A Potential Mechanism for Steroid Resistance in Severe Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med; A31. Asthma therapy: glucocorticoids and beyond; 2016. pp. A7771–A7771. (poster) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Network of interactions between the 6 microRNAs and their targets (gene ID of the isoforms) in the Total cytoplasmic fraction. Note the 2 subnetworks corresponding to microRNAs up-regulated and their down-regulated targets and vice versa (HTML).

Network of interactions between the 6 microRNAs and their targets (gene ID of the isoforms) in polyribosome bound mRNAs. Note the 2 subnetworks corresponding to microRNAs up-regulated and their down-regulated targets and vice versa. The 2 subnetworks are connected via GFOD1, since this gene presents 2 differentially expressed isoforms (one up-regulated and one down-regulated) that share the same 3′UTR (HTML).