Abstract

Background

The boxed warning (also known as ‘black box warning [BBW]’) is one of the strongest drug safety actions that the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) can implement, and often warns of serious risks. The objective of this study was to comprehensively characterize BBWs issued for drugs after FDA approval.

Methods

We identified all post-marketing BBWs from January 2008 through June 2015 listed on FDA’s MedWatch and Drug Safety Communications websites. We used each drug’s prescribing information to classify its BBW as new, major update to a preexisting BBW, or minor update. We then characterized these BBWs with respect to pre-specified BBW-specific and drug-specific features.

Results

There were 111 BBWs issued to drugs on the US market, of which 29% (n = 32) were new BBWs, 32% (n = 35) were major updates, and 40% (n = 44) were minor updates. New BBWs and major updates were most commonly issued for death (51%) and cardiovascular risk (27%). The new BBWs and major updates impacted 200 drug formulations over the study period, of which 64% were expected to be used chronically and 58% had available alternatives without a BBW.

Conclusions

New BBWs and incremental updates to existing BBWs are frequently added to drug labels after regulatory approval.

Keywords: Black box warning, boxed warning, drug labeling, drug safety, food and drug administration

1. Introduction

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) utilizes multiple tools to maximize drug safety after initial regulatory approval, including safety communications, label changes, boxed warnings (also known as ‘black box warnings [BBWs]’), and, in rare cases, withdrawals. The BBW is one of FDA’s strongest warnings, used to inform patients and clinicians about serious potential adverse reactions such as those resulting in death or inpatient hospitalization, to highlight precautions that can be taken to decrease the likelihood of adverse reactions, or to emphasize restrictions to assure safe prescription drug use [1]. In a BBW, the manufacturer briefly describes the risks of the drug in the prescribing information and surrounds the text with a black box. FDA communicates BBWs via public notices, and BBW content must be included in print or broadcast advertisement. Drug manufacturers can initiate BBWs, but FDA initiates the vast majority; most safety-related label changes are based on adverse event reports or clinical trial data [2].

BBWs may be applied at the time of a drug’s regulatory approval or in the post-marketing period if safety issues emerge. Of novel therapeutics approved between 1996 and 2012, almost three quarters of BBWs were issued at the time of FDA approval, but over 40% of drugs receiving BBWs acquired the warnings in the post-marketing period [3]. Additionally, a recent study found that FDA took significant post-marketing safety actions for approximately one-third of novel therapeutics approved between 2001 and 2010, most commonly issuing a new BBW [4]. Further, the likelihood of drugs approved since the passage of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) in 1992 receiving post-marketing BBWs or being withdrawn has increased compared to drugs approved before this period [5].

Despite FDA’s increasingly frequent use of BBWs as a tool to support safer drug prescribing, no study has comprehensively characterized BBWs issued for drugs after initial regulatory approval, including the type of safety concern identified and the patient population determined to be at-risk. We therefore identified and characterized all new and incremental BBWs, including major and minor updates, between January 2008 and June 2015, in order to better understand how this important regulatory tool is used by FDA.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and study sample

To identify all new and incremental (defined as major and minor updates) BBWs from January 2008 through June 2015, we used MedWatch [6]. MedWatch is FDA’s primary safety information and adverse event reporting program, compiling reports by healthcare professionals, patients, and others. We searched MedWatch’s Drug Safety Labeling Changes webpages, which provide monthly summaries of all safety-related labeling changes, including BBWs. We supplemented our MedWatch-based dataset by examining every FDA Drug Safety Communication between January 2008 and June 2015 (614 communications), and included additional BBWs not listed on MedWatch. We also included BBWs identified in relevant BBW literature [4,7].

For each BBW, we identified the prescribing information associated with the new or incremental BBW using Drugs@FDA. This database contains prescribing information, approval information, and other FDA regulatory information for most approved drugs [8]. The prescribing information, also known as professional labeling or drug labeling, summarizes the ‘essential scientific information needed for the safe and effective use of the drug’ [9]. We compared language in the full BBWs (not the highlights on the first page of the prescribing information) to identify all potential BBW text changes between the prescribing information associated with the BBW and the most recent version of the prescribing information available before the BBW. If prescribing information was not available on Drugs@FDA, we used the relevant edition of the Physicians’ Desk Reference (PDR) to locate the prescribing information. We excluded BBWs for which we could not access both before and after BBW prescribing information from either Drugs@FDA or PDR, because we could not verify whether and what type of BBW change had occurred.

2.2. Classification of BBWs

We classified each BBW as either ‘new BBW,’ ‘major update to a preexisting BBW,’ ‘minor update to a preexisting BBW,’ ‘removal of information from a preexisting BBW,’ or ‘no change to a preexisting BBW.’ Major updates were defined as changes that would meaningfully affect the clinical use of the drug, while minor updates were defined as changes that would not be expected to substantively impact the clinical use of a drug. Supplementary Table 1 describes the criteria used to classify BBWs into these categories. If a BBW contained components of both major and minor updates (e.g. simultaneous addition of a fatal toxicity and a drug-drug interaction), we classified the update as major. This approach was consistent with a recent study by FDA authors investigating pre-marketing factors associated with postmarketing BBWs and safety withdrawals [10]. All BBWs were reviewed and classified by one author (MTS), and all cases of uncertainty were reviewed by at least one additional author (JSR and/or SSD).

After comparing the BBW language, we looked for commonalities in the BBWs across different drugs. If multiple drugs or multiple formulations of the same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) received the same BBW, we recorded the different drugs and formulations that were impacted by the BBW, but we considered this to be one unique BBW. For example, since onabotulinumtoxinA injection (Botox) and rimabotulinumtoxinB injection (Myobloc) received the same BBW for risk of spread of toxin, this warning was considered to be one BBW.

For BBWs applying to multiple formulations of the same drug, we recorded each formulation separately; for drugs with multiple formulations in the same category (e.g. oral capsule and orally disintegrating tablet, where both are ‘oral capsules/tablets’), we only included one formulation in each category. Branded drugs containing the same API but with different brand names were counted as separate formulations, as they typically contain separate prescribing information; branded drugs and their generic equivalents were not counted separately.

2.3. Characterization of BBWs and drugs receiving BBWs

We characterized all BBWs according to warning type, relevant patient population, inclusion in a class warning, drug-drug interaction, monitoring requirements, pediatric health risk, and presence of a Risk Evaluation & Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program involving Elements To Assure Safe Use (ETASU). Warning type and relevant patient population were not determined for minor BBW updates; by our definition, a new warning type or new information about an at-risk patient population would likely substantively impact clinical practice, and thus be a major BBW update. To determine warning type, we looked for new or substantively updated risks, and classified them into the following categories, including multiple if appropriate: death, cardiovascular, oncologic, fetal toxicity, hepatotoxic, neuropsychiatric, neurologic, vision loss/ophthalmologic, metabolic, renal, musculoskeletal, hematologic, infectious, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, infusion reaction/anaphylactic, and cutaneous. Relevant patient population was determined based on the BBW, and was defined as applying to the entire population indicated for the drug (general), to a specific population, or to the general population indicated for the drug but with a higher risk identified in a specific subpopulation. Drug-drug interactions were defined as contraindications for coadministration of drugs specified in the BBW, including alcohol or smoking. We also abstracted BBW monitoring requirements, such as measurement of liver function tests prior to initiation of a drug with a BBW for hepatotoxicity. Pediatric health risk was defined as a BBW where the primary addition or modification described a risk related to a pediatric indication or where the ultimate effect of the risk is in children. For example, testosterone gels received a warning for virilization in children who were secondarily exposed to the gels; this BBW was considered pediatric. We used FDA’s REMS@FDA database to identify ETASU REMS, which are the most extensive FDA-mandated risk management plans and involve required actions by clinicians or pharmacists to prescribe or dispense a drug [11].

Additionally, we characterized each drug affected by a BBW according to the following: drug class, therapeutic area, year of initial FDA approval, formulation, inclusion in a combination product involving multiple APIs, availability of alternatives for the primary FDA-approved indication(s), and expected duration of use. We determined the drug class (i.e. pharmaceutical or biologic) based on whether the manufacturer’s initial regulatory application was a New Drug Application (i.e. small molecule or ‘pharmaceutical’) or Biologics License Application (i.e. product with complex structure derived from living material or ‘biologic’). We used the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Index to determine the therapeutic class. Year of initial FDA approval was categorized into 5-year time periods correlating with renewals of PDUFA since its passage in 1992. We used eight formulation categories: oral tablets/capsule; oral solution, which includes solutions, suspensions, and lozenges; subcutaneous injection; intravenous infusion; intramuscular injection; topical cream/gel; transdermal, which includes vaginal rings; and inhaled. To identify the availability of alternative therapies for the primary FDAapproved indication(s), we used the U.S. Pharmacopeia Convention Medicare Model Guidelines (Categories & Classes) versions 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0 in conjunction with our clinical judgment, reviewing all FDA-approved therapies for the FDA-approved indications of each drug in our sample. We used the most recent U.S. Pharmacopeia version available before each drug’s BBW; for BBWs before version 5.0 was released, we used version 5.0 and verified the availability of alternatives at the time of BBW using Drugs@FDA. We classified alternative availability as: none, if it was the only drug available for its primary FDA-approved indication(s); alternatives with BBWs, if all available alternatives had a BBW; or alternatives without BBW, if at least one alternative for the drug’s primary FDA-approved indication did not have a BBW. We did not take the severity of the alternatives’ BBWs into account, and only considered whether or not the alternatives had BBWs. Expected duration of use for the primary FDAapproved indication(s) was determined based on the prescribing information, UpToDate.com, and clinical judgment; it was categorized as acute (<1 month), intermediate (1 month to 2 years), or chronic use (>2 years).

2.4. Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the sample. New BBWs and major updates were grouped together for analyses because both contain practice-altering information and because major updates often contain new risks compared to previous BBWs. All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel version 15.32 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Because this project used publicly-available data that did not involve human subjects, it was exempt from review by the Yale Human Research Protection Program.

3. Results

3.1. BBWs from January 2008 through June 2015

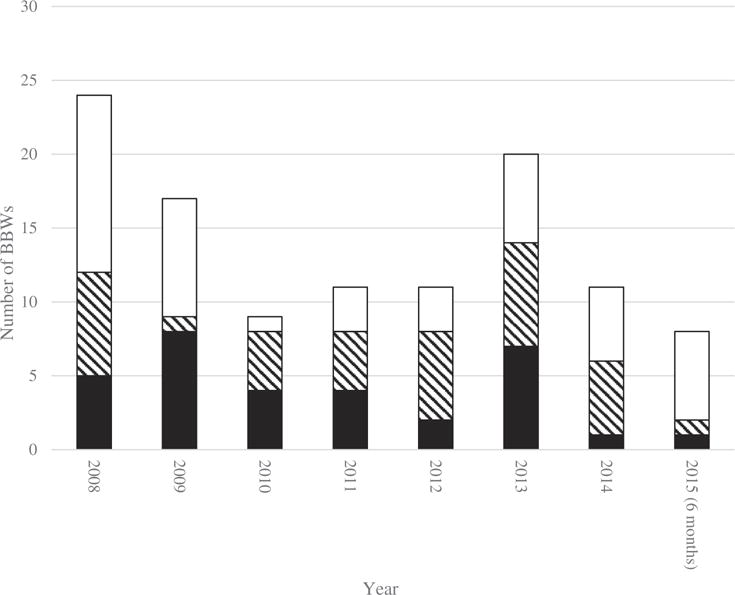

We identified 122 new and incremental (i.e. major or minor update) BBWs issued between January 2008 and June 2015. Of these BBWs, 114 were identified from MedWatch, while an additional six were identified from FDA Drug Safety Communications and two were identified from BBW literature. We excluded 11 BBWs, including those issued for nontherapeutic agents such as a contrast agents (n = 5), those that primarily involved removal of information from the BBW (n = 4), or if we were unable to verify the BBW update content through prescribing information (n = 2). The remaining 111 BBWs affected 192 unique APIs or combinations and 314 distinct formulations. Of the 192 APIs, new or incremental BBWs were issued for 28% (n = 53) at two or more time points, and 22% (n = 42) received BBWs for at least two formulations. Supplementary Table 2 contains the APIs impacted by BBWs and the classification of their BBWs. Of the 111 BBWs in our sample, 29% (n = 32) represented the first BBW for a drug, 32% (n = 35) were major updates to an existing BBW, and 40% (n = 44) were minor updates to an existing BBW (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of annual postmarket BBWs from January 2008 through June 2015.

BBW = Black Box Warning.

3.2. Characteristics of new BBWs and major BBW updates

Characteristics of the 67 new and major BBW updates are summarized in Table 1. Among these, 51% (n = 34) were for death, 27% (n = 18) for cardiovascular risk, and 12% (n = 8) for hepatotoxicity. In 46% (n = 31), the BBWs included new or updated information about risks to the general population indicated for the drug; in 28% (n = 19), the new or updated information described risks in specific patient populations; 25% (n = 17) described risks to the general population indicated for the drug and specified specific subpopulations at higher risk. For 22% (n = 15), the BBW was a class warning. The median number of formulations impacted by these class warnings was 6 (interquartile range [IQR], 2–12 formulations). There was a new ETASU REMS associated with 4% (n = 3) of these BBWs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of new and incremental BBWs.a

| BBW component category | BBW component value | All new BBWs & major updates: No. (% of new and major updates) | New BBW: No. (% of new) | Major update: No. (% of major updates) | Minor update: No. (% of minor updates)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warning typeb | Death | 34 (51) | 20 (63) | 14 (40) | n/a |

| Cardiovascular | 18 (27) | 9 (28) | 9 (26) | n/a | |

| Oncologic | 6 (9) | 2 (6) | 4 (11) | n/a | |

| Fetal toxicity | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | n/a | |

| Hepatotoxic | 8 (12) | 5 (16) | 3 (9) | n/a | |

| Neuropsychiatric | 2 (3) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | n/a | |

| Neurologic | 4 (6) | 3 (9) | 1 (3) | n/a | |

| Vision Loss/Ophthalmologic | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | n/a | |

| Metabolic | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | n/a | |

| Renal | 4 (6) | 3 (9) | 1 (3) | n/a | |

| Musculoskeletal | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | n/a | |

| Hematologic | 2 (3) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | n/a | |

| Infectious | 6 (9) | 4 (13) | 2 (6) | n/a | |

| Pulmonary | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | n/a | |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | n/a | |

| Infusion Reaction/Anaphylactic | 4 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | n/a | |

| Cutaneous | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | n/a | |

| Patient population | Total | 67 (100) | 32 (100) | 35 (100) | n/a |

| General | 31 (46) | 19 (59) | 12 (34) | n/a | |

| Specific population | 19 (28) | 4 (13) | 15 (43) | n/a | |

| General with high risk in specific population | 17 (25) | 9 (28) | 8 (23) | n/a | |

| Pediatric | 8 (12) | 3 (9) | 5 (14) | 3 (7) | |

| Class warning | 15 (22) | 7 (22) | 8 (23) | 8 (18) | |

| Drug-Drug interaction | 3 (4) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 5 (11) | |

| Monitoring | 27 (40) | 10 (31) | 17 (49) | 2 (5) | |

| ETASU REMS | Total | 67 (100) | 32 (100) | 35 (100) | 44 (100) |

| BBW accompanied by ETASU REMS | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | |

| ETASU REMS already in place | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 4 (9) | |

| No ETASU REMS before or immediately after BBW | 59 (88) | 32 (100) | 27 (77) | 40 (91) | |

| BBW accompanied by removal of ETASU REMS | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

BBW: Black Box Warning; ETASU: Elements To Assure Safe Use; REMS: Risk Evaluation & Mitigation Strategy.

Sums of percentages may not equal the total percentage due to rounding.

New BBWs and major BBW updates were classified under all applicable warnings types.

BBW updates that included new or substantially updated information about a risk or patient population were classified as major updates; therefore, warning type and patient population were not classified for minor updates.

3.3. Characteristics of drugs experiencing new BBWs and major updates

The 67 new BBWs and major updates impacted 127 unique APIs. Of these 127 APIs, 22% (n = 28) received BBWs for at least two formulations of the API and 23% (n = 29) received BBWs during multiple time points, thereby impacting 200 API formulations over the entire study period. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the API formulations impacted by new BBWs and major updates. Among these API formulations, 91% (n = 182) were pharmaceuticals and 9% (n = 18) were biologics. Thirty percent were nervous system drugs (n = 60) and 19% were antiinfectives for systemic use (n = 37). Initial regulatory approval occurred before 1992 for 37% (n = 74) of these formulations, with 66% (n = 49) of these pre-1992 drugs included in class warnings (Table 3). There were alternative drugs available that did not have BBWs for 58% (n = 116) of API formulations receiving new BBWs and major updates; 36% (n = 72) had alternative drugs available, but the alternatives also had BBWs. Sixty-four percent (n = 128) of new BBWs and major updates applied to API formulations expected to be used chronically for the primary FDA-approved indication(s), with 25% (n = 49) with expected use in the acute setting and 12% (n = 23) with expected use of intermediate duration.

Table 2.

Characteristics of drug formulations receiving new and incremental BBWs.a

| Drug category | Drug value | All new BBWs & major updates: No. (% of new and major updates) | New BBW: No. (% of new) | Major update: No. (% of major updates) | Minor update: No. (% of minor updates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Total | 200 (100) | 61 (100) | 139 (100) | 111 (100) |

| Pharmaceutical | 182 (91) | 53 (87) | 129 (93) | 89 (80) | |

| Biologic | 18 (9) | 8 (13) | 10 (7) | 22 (20) | |

| Therapeutic area (ATC) | Total | 200 (100) | 61 (100) | 139 (100) | 111 (100) |

| A: Alimentary tract and | 13 (7) | 5 (8) | 8 (6) | 7 (6) | |

| metabolism | |||||

| C: Cardiovascular system | 29 (15) | 0 (0) | 29 (21) | 7 (6) | |

| G: Genitourinary system and | 12 (6) | 4 (7) | 8 (6) | 7 (6) | |

| sex hormones | |||||

| J: Antiinfectives for systemic | 37 (19) | 14 (23) | 23 (17) | 23 (21) | |

| use | |||||

| L: Antineoplastic and | 24 (12) | 8 (13) | 16 (12) | 20 (18) | |

| immunomodulating agents | |||||

| N: Nervous system | 60 (30) | 18 (30) | 42 (30) | 27 (24) | |

| R: Respiratory system | 9 (5) | 0 (0) | 9 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 16 (8) | 12 (20) | 4 (3) | 20 (18) | |

| Formulation | Total | 200 (100) | 61 (100) | 139 (100) | 111 (100) |

| Oral tablet/capsule | 125 (63) | 31 (51) | 94 (68) | 55 (50) | |

| Oral solution | 13 (7) | 4 (7) | 9 (6) | 12 (11) | |

| Subcutaneous injection | 7 (4) | 2 (3) | 5 (4) | 25 (23) | |

| Intravenous infusion | 26 (13) | 15 (25) | 11 (8) | 11 (10) | |

| Intramuscular injection | 5 (3) | 5 (8) | 0 (0) | 6 (5) | |

| Topical cream/gel | 4 (2) | 3 (5) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Transdermal | 12 (6) | 1 (2) | 11 (8) | 1 (1) | |

| Inhaled | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | 8 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Combination drug | 35 (18) | 7 (11) | 28 (20) | 12 (11) | |

| Alternatives | Total | 200 (100) | 61 (100) | 139 (100) | 111 (100) |

| No alternatives available | 12 (6) | 5 (8) | 7 (5) | 4 (4) | |

| Alternatives available and at | 116 (58) | 38 (62) | 78 (56) | 37 (33) | |

| least one without BBW | |||||

| Alternatives available but have | 72 (36) | 18 (30) | 54 (39) | 70 (63) | |

| BBW | |||||

| Expected duration of use | Total | 200 (100) | 61 (100) | 139 (100) | 111 (100) |

| Acute (<1 Month) | 49 (25) | 31 (51) | 18 (13) | 11 (10) | |

| Intermediate (1–24 Months) | 23 (12) | 15 (25) | 8 (6) | 22 (20) | |

| Chronic (>24 Months) | 128 (64) | 15 (25) | 113 (81) | 78 (70) |

BBW: Black Box Warning.

Sums of percentages may not equal the total percentage due to rounding.

Table 3.

Year of initial FDA approval and inclusion in class warning for drug formulations receiving new and incremental BBWs.

| Year of initial FDA approval

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1992 | 1992–1996 | 1997–2001 | 2002–2006 | 2007 or later | ||

| All new BBWs & major updates | Class warnings | 49 | 9 | 27 | 17 | 10 |

| Non-class warnings | 25 | 9 | 17 | 20 | 17 | |

| Total | 74 | 18 | 44 | 37 | 27 | |

| New BBW | Class warnings | 16 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 0 |

| Non-class warnings | 7 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 7 | |

| Total | 23 | 4 | 13 | 14 | 7 | |

| Major BBW update | Class warnings | 33 | 6 | 19 | 12 | 10 |

| Non-class warnings | 18 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 10 | |

| Total | 51 | 14 | 31 | 23 | 20 | |

| Minor BBW update | Class warnings | 17 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 6 |

| Non-class warnings | 9 | 10 | 18 | 12 | 13 | |

| Total | 26 | 18 | 29 | 19 | 19 | |

BBW: Black Box Warning; FDA: U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

3.4. Characteristics of minor BBW updates

Of the 44 minor BBW updates, 18% (n = 8) were minor modifications to the language in class warnings, such as the class warning for mortality in elderly patients taking certain antipsychotics (Table 1). The median number of formulations impacted by these class warnings was 6 (IQR, 3–4 formulations). Addition of drugs to a list of drug-drug interactions was a component of 11% (n = 5) of minor updates, and inclusion of monitoring requirements contributed to 5% (n = 2). The remainder of the minor updates involved modifications such as syntactical changes or addition of detail about risks previously included in the BBW.

3.5. Characteristics of drugs experiencing minor updates

The 44 minor BBW updates were issued across 65 unique APIs, of which 26% (n = 17) received BBWs for multiple formulations of the API and 18% (n = 12) experienced BBWs at multiple time points. The 65 APIs therefore spanned 111 API formulations over the study period (Table 2). Eighty percent (n = 89) of these API formulations were pharmaceuticals and 20% (n = 22) were biologics.

4. Discussion

We comprehensively characterized all new and incremental BBWs issued for prescription drugs and biologics between 2008 and June 2015 to provide a more complete understanding of BBW characteristics and the drugs for which they are issued. The new and major BBW updates in our sample commonly contained serious risks such as death and cardiovascular risk, indicating that important data regarding the most serious safety concerns often emerge in the post-marketing setting after initial drug approval. This dynamic may reflect the limitations of pre-marketing data: given that the majority of pivotal trials used by FDA for approval decisions contain a narrow patient population and limited follow-up period [4,12], and that the near-majority use surrogate endpoints as their primary outcome [13], many risks may not be identified until after a drug is approved and then used in a larger population and with longer follow-up. Further, the majority of new and incremental BBWs were issued for drugs that are typically taken for durations over 2 years, putting patients at risk for potentially fatal and preventable risks for extended time periods.

In addition to describing serious risks, the new and major BBW updates often contained vital practice-guiding information such as monitoring requirements and descriptions of specific populations at risk for adverse events, highlighting the importance of ensuring clinician awareness of these BBWs. As safer available alternatives were available for more than half of drugs for which new BBWs and major updates were issued, such knowledge could inform safer prescribing. Prior research has shown that BBWs have variable impact on clinician prescribing behavior, and so tools to facilitate safer prescribing are needed [14–16].

Drugs approved with a BBW are more likely to receive an incremental BBW after FDA approval, and post-marketing BBWs may be issued many years after initial regulatory approval [2,10]. Indeed, initial FDA regulatory approval was granted before 1992 for a substantial number of the drugs receiving new BBWs and major updates in our sample. This dynamic could reflect the higher number of APIs granted regulatory approval before 1992 compared to the subsequent 5-year intervals used in our sample. Additionally, the sizeable number of these pre-1992 drugs impacted by BBWs issued in 2008 or later could stem from the large number of drugs included in classes impacted by BBWs such as opioids and antipsychotics. Alternatively, the increased focus on pharmacovigilance as part of PDUFA IV starting in 2007 may have increased the detection rate of adverse events, thereby contributing to an increase in the number of BBWs issued during our study period [17].

Our findings are consistent with the observation that postmarketing BBWs are often updates to existing BBWs, and they underscore the need for patient and clinician awareness of these warnings in prescribing decisions. However, given increasing constraints on clinicians’ time, additional systems should be implemented to support clinician prescribing by monitoring for BBW updates and ensuring that the latest BBW information is incorporated in clinical practice. For example, systems such as clinical decision support tools in electronic health records or payer formulary management tools such as formulary exclusion, prior authorization, or step therapy could promote safer prescribing [18]. Additionally, since the vast majority of new and incremental BBWs were not associated with ETASU REMS, FDA is rarely monitoring distribution of drugs with these BBWs. While ETASU REMS have been associated with changes in prescribing [19,20], the evidence for the impact of BBWs on formulary coverage and prescribing is not consistent. This limited regulatory monitoring further underscores the importance of implementing tools to support clinician awareness of BBWs.

Our study has limitations. Our methodology relies on the completeness of FDA’s MedWatch and Drugs@FDA databases; while MedWatch is maintained by FDA, it may not document all changes to BBWs. Additionally, Drugs@FDA did not contain labels for all drugs before or after they received a BBW, which limited our ability to verify that a new or updated BBW had occurred; however, this limitation only occurred for two BBWs.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides the first comprehensive review of new and incremental BBWs issued after regulatory approval over an extended time period, including the content of the warnings and the characteristics of the drugs for which they were issued. We observed 111 such BBWs, of which 60% (n = 67) were new or major updates. These BBWs were commonly issued for pharmaceutical drugs with expected use greater than 2 years and with safer available alternatives. Most BBWs contained vital clinical information, such as information about possibility of death, specific populations at risk, and monitoring that can mitigate these risks. These dynamics highlight the need for clinicians to keep apprised of changes to BBWs after regulatory approval in order to be fully equipped with information about the risks of prescription drugs. Additionally, as the regulatory process and standards used by FDA continue to evolve, a more thorough examination of the use and impact of BBWs will be critical.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This paper was funded by NIH training grant award T35DK104689.

Mr. Solotke received a student research grant provided by the Yale School of Medicine Office of Student Research under NIH training grant award T35DK104689 (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented. Over the past 36 months, Dr. Ross received support from the Food and Drug Administration as part of the Centers for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) program. Dr. Ross also received support through Yale University from Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from Medtronic, Inc. and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop methods for postmarket surveillance of medical devices, from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association to better understand medical technology evaluation, from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting, from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to examine community predictors of healthcare quality, and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which established the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency (CRIT) at Yale University. Dr. Dhruva is funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Over the past 36 months, Dr. Shah received support from the Food and Drug Administration as part of the Centers for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) program. In addition, Dr. Shah received support through the Mayo Clinic from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1•.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: warnings and precautions, contraindications, and boxed warning sections of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products – content and format. 2011 Oct 11; [cited 2017 Dec 08]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm075096.pdf FDA Guidance Document detailing situations that may require a BBW and what information should be included in BBWs.

- 2.Lester J, Neyarapally GA, Lipowski E, et al. Evaluation of FDA safetyrelated drug label changes in 2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:302–305. doi: 10.1002/pds.3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Cheng CM, Shin J, Guglielmo B. Trends in boxed warnings and withdrawals for novel therapeutic drugs, 1996 through 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1704–1705. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4854. Study showing that BBWs were acquired after initial regulatory approval for over 40% of drugs receiving BBWs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4•.Downing NS, Shah ND, Aminawung JA, et al. Postmarket safety events among novel therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration between 2001 and 2010. JAMA. 2017;317:1854–1863. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5150. Recent study showing that BBWs are one of FDA’s most commonly used postmarket safety actions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank C, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, et al. Era of faster FDA drug approval has also seen increased black-box warnings and market withdrawals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1453–1459. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. MedWatch: the FDA safety information and adverse event reporting program. [cited 2017 Dec 08]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/default.htm.

- 7.Winterfield L, Vleugels RA, Park KK. The value of the black box warning in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:660–666. Epub 2015 Jul 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. [cited 2017 Dec 08]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/

- 9.Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21-food and drugs. Revised as of 2016 Apr 1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schick A, Miller KL, Lanthier M, et al. Evaluation of pre-marketing factors to predict post-marketing boxed warnings and safety withdrawals. Drug Saf. 2017;40:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s40264-017-0526-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. REMS@FDA: approved risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) [cited 2017 Dec 08]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/

- 12.Downing NS, Shah ND, Neiman JH, et al. Participation of the elderly, women, and minorities in pivotal trials supporting 2011–2013 U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals. Trials. 2016;17:199. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, et al. Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents, 2005–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:368–377. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282034. Epub 2014 Jan 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusetzina SB, Higashi AS, Dorsey ER, et al. Impact of FDA drug risk communications on health care utilization and health behaviors: a systematic review. Med Care. 2012;50:466–478. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasser KE, Seger DL, Yu DT, et al. Adherence to black box warnings for prescription medications in outpatients. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:338–344. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner AK, Chan KA, Dashevsky I, et al. FDA drug prescribing warnings: is the black box half empty or half full? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:369–386. doi: 10.1002/pds.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Food Drug Administration. Prescription drug user fee act (PDUFA) IV drug safety five-year plan: 2008–2012. 2008 [cited 2017 Dec 08]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/PrescriptionDrugUserFee/UCM119244.pdf.

- 18.Dhruva SS, Karaca-Mandic P, Shah ND, et al. Association between FDA black box warnings and medicare formulary coverage changes. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(9):e310–e315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchette CM, Nunes AP, Lin ND, et al. Adherence to risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) requirements for monthly testing of liver function. Drugs Context. 2015;4:1–10. doi: 10.7573/dic.212272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiSantostefano RL, Yeakey AM, Raphiou I, et al. An evaluation of asthma medication utilization for risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) in the United States: 2005–2011. J Asthma. 2013;50:776–782. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.803116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.