Introduction

Numerous preclinical animal studies have shown beneficial effects of cell therapies after stroke, including reduction of functional deficits and lesion size. Early stage clinical studies currently aim to confirm this therapeutic potential. Despite the progress in translating cell therapy for stroke, “true” cell replacement and stem cell-based tissue regrowth have not been achieved yet. Multimodal regeneration-improving effects (MRIEs), such as immunomodulation or paracrine growth factor support, are considered the primary mechanisms of action in cell therapies.1 This is not surprising for systemically administered adult progenitor or mixed populations, which typically do not enter brain tissue. However, even brain tissue-derived cells that, in principle, have the ability to give rise to neurons and glia are thought to exert their therapeutic benefits mainly via MRIEs.2 Current clinical trials are designed to reflect this supportive role of cell therapy rather than tissue reconstruction.3

Our increasing understanding of brain development on the one hand and post-stroke pathophysiology on the other illustrate the challenges in true tissue restoration. First, tissue replacement requires a perfect synchronization between participating cells and the host tissue in spatial, temporal, and functional dimensions.1 Second, anatomical cues being decisive for brain tissue growth during embryo-/fetogenesis rapidly decline in post-natal brain maturation.4 Third, major brain lesions cause a hostile local environment that detrimentally impacts graft survival and integration. Fourth, restoring brain tissue requires adequate blood supply, posing a major challenge in larger lesions and bigger brains.5 Fifth, lack of adequate functional interaction between host tissue and the graft leads to tissue restoration failure.6

To go beyond MRIEs, a careful orchestration of therapeutic approaches relying on and promoting endogenous (e.g., neurogenesis-based) and/or exogenous (e.g., stem cell transplantation-based) tissue restoration need to be established. Selection of appropriate, restoration-permissive target lesions will also be required to enhance chances for successful tissue regeneration. Herein, we propose a four-component in vivo research strategy with the potential to foster tissue repair and replacement in stroke.

Component 1: Selection of restoration-permissive stroke models

Large territorial ischemic lesions

Preclinical research and clinical studies focus on large territorial lesions. These represent a major proportion of strokes in patients and exhibit salvageable tissue for acute neuroprotective interventions. However, exactly this lesion type may be the hardest to repopulate due to the large volume, a hostile intra- and perilesional microenvironment, and massively disturbed local blood supply. Consequently, tissue restoration was hardly observed in animal models of large territorial lesions, even when graft differentiation and integration were initially successful.6 More specialized stroke models may mimic clinical stroke subtypes and cofactor profiles being less challenging or even supportive of tissue restoration.

Lacunar infarcts and white matter injuries

Small, lacunar-like lesions involving white matter represent 20-25% of all strokes 7 Lacunar infarcts can be induced by potent vasoconstrictors such as endothelin-1 (ET-1) or photothrombosis. They are interesting for tissue repair strategies since the tissue volume to restore is small and anatomical structures are preserved.Endogenous or graft-borne cells repopulating the lesion have easier access to blood supply from surrounding, unaffected areas. Lacunar infarcts often affect white matter areas.

However, experimental models of lacunar lesions are rarely used because of some challenges. First, the white matter content in rodents is smaller than in humans.8 Second, inducing small, reproducible lesions in deep brain structures is technically demanding. Third, behavioral deficits are mild, so animals often recover rapidly even without a therapeutic intervention. Thus, there is a need for reliable subcortical white matter injury models with substantial functional impairment. Some existing models come close to this demand.

Global white matter injury models, such as bilateral common carotid artery occlusion, produce chronic, but diffuse and extended, damage which may be hard to repopulate.9 Hypertensive rats spontaneously develop both punctuate and diffuse white matter lesions, and cognitive impairment.10 Focal white matter injury can be induced by ET-1. The vasoconstrictor is injected stereotactically into the corpus callosum to damage axons projecting to the contralateral cortex, or into the posterior internal capsule, which contains corticospinal tract and thalamic sensory projections.ET-1 injections into the corpus callosum induces impairments on grid walking in aged mice.11 The model also causes long-term cognitive impairment in novel object recognition tasks, but no apparent deficit in the cylinder or grid-walking tests, locomotor activity, water maze or Y-maze in mice.12 Intact fibers in the corpus callosum compensate the damage, explaining minor behavioral deficits. ET-1 injections into the internal capsule produce a more robust behavioral deficit. Importantly, behavioral impairment severity varies according to injection site.Only animals with lesions in the most posterior location show a long-term deficit in adhesive removal, cylinder, and foot-fault test. Selection of vasoconstrictor and angle of the injection is critical.13 ET-1-induced white matter lesions potentially facilitate targeted restorative therapy developments.11

Cerebral hemorrhages

Intracerebral hemorrhages (ICH) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are the main subtypes of hemorrhagic stroke, accounting for 10-15% and 6-8% of all strokes, respectively. They share important comorbidities with ischemic stroke, occur unaccompanied or as an important complication of ischemic stroke treatment and prevention.14 Recent experimental evidence suggests that the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke are different. Specifically, the hematoma and blood breakdown products released from the bleeding cause secondary, delayed damage leading to neuronal cell death.15 Therapeutic strategies being different from those employed for ischemic stroke are needed to promote tissue repair after hemorrhagic stroke.

Most preclinical ICH studies use one of two large hemorrhage rodent models: intracerebral injection of either autologous blood or bacterial collagenase that degrades the endothelial basement membrane. Replacing brain tissue in a large hematoma cavity poses similar challenges as for large ischemic lesions and may require biomaterial support (see below). Moreover, these models do not mimic spontaneous occurrence of hemorrhage. On the other hand, using models with spontaneously developing hemorrhages is challenging due to the difficulty to detect their occurrence and variable lesion sizes and locations. In a large study in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats, 7.4% showed bleeding and 17.9% hemorrhagic transformation in various locations.16

Some genetic models have been developed to mimic cerebral microbleeds.17,18 Cerebral microbleeds cause small lesions that, theoretically, may foster tissue repair approaches. However, they are often clinically silent 19 and are hard to access, particularly when situated in subcortical regions. Therefore, they are currently no target for therapeutic approaches of tissue restoration.

Large animal models of lacunar infarcts, white matter injury and hemorrhagic stroke

Gyrencephalic large animals exhibit higher percentage of white matter 8 and some specialized large animal ischemia models feature focal white matter lesion.20,21 However, those are not yet widely applied in preclinical research. Moreover, only few studies investigate white matter changes following hemorrhagic stroke, although the underlying mechanisms may facilitate cell-based tissue repair.White matter injury can be investigated in a piglet model of autologous blood injection into the frontal lobe.22 Some preclinical studies demonstrated that white matter damage also occurs in the rodent corticospinal tract after ICH 23 and cortical projections are lost early after ICH in mice.24 Understanding of how brain hemorrhage leads to white matter changes, preferably in models with comparable brain white matter content, should be a research priority, and will help develop strategies for white matter repair and regeneration.

Hematoma resolution in humans takes much longer than in rodents because of bigger absolute hematoma volumes, which can be modeled in larger animals. There are models of autologous blood injection into the ventricle or frontal lobe of piglets.25 Large animal models also provide the opportunity to investigate tissue repair strategies following hematoma evacuation, especially combinatorial treatments involving biomaterials and pharmacologic agents.

Component 2: Use of supportive biomaterials

Biomaterials offer novel avenues to treat brain damage and support tissue regeneration. A major advantage of biomaterials is the potential for controlled local release of growth factors, anti-inflammatory agents, and guidance cues at a specific dose over a given time.26 Many synthetic (e.g., polyethylene glycol) and natural biomaterials (e.g., hyaluronic acid) have favorable biocompatibility and do not invoke an adverse host response. However, invasive intracerebral delivery is required to deposit materials at the appropriate site.27 This approach avoids systemic effects of compounds and does not interfere with other brain regions. It can also circumvent the challenge of delivering large molecules across the blood-brain barrier (Figure 1).

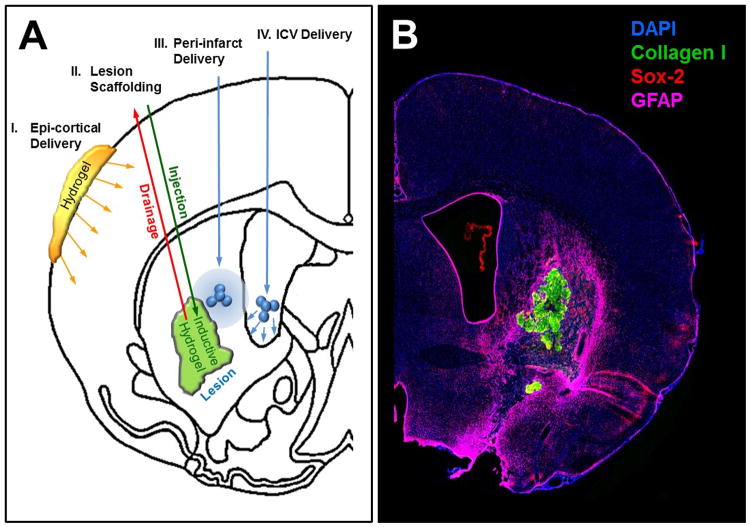

Figure 1. Application of biomaterials in repairing stroke brain.

(A) Biomaterials enable local release of factors and/or provide structural support in case of tissue loss. The least invasive means to deliver factors to the stroke damage brain is by the epi-cortical placement of biomaterials, such as hydrogel, releasing factors into the surrounding cortex (I.). Hydrogels can also serve as a scaffolding material in the lesion cavity (II.). An injection-drainage approach is preferable to ensure homogenous filling of the volume. Repair response in the peri-infarct area can be influenced by injecting microparticles that release growth factors, and that would not easily penetrate across the blood-brain barrier (III.). Injection of microparticles into the lateral ventricle (IV.) can be used to influence the sub-ependymal zone to increase neurogenesis. (B) Exemplary overview immunofluorescent staining of brain slice showing ECM hydrogel (detected by collagen I in green) in the lesion cavity.

Controlled release of factors is achieved either by incorporation or by conjugation of a factor into microspheres/particles or hydrogels. Microspheres will typically not change shape upon injection, whereas hydrogel will more easily permeate through tissue. Microparticle incorporation of fenofibrate, brain-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor have been used in stroke.28 Efficacy of these approaches is dependent on the distribution of microparticles and their sphere of influence on damaged tissue. Hydrogels can permeate more extensively and potentially exert more significant functional effects, such as polarizing microglia/macrophages towards and M2 phenotype that support tissue repair.29 A continued stimulation of the endogenous stem cell pool only requires an epi-cortical placement of a hydrogel to deliver epidermal growth factor.30 The time-controlled sequential release of multiple factors promoting tissue repair is an opportunity to increase the complexity of approaches that promote tissue repair.

Apart from tissue damage in stroke, there is a complete regional loss of tissue integrity that leads to cavitation in which the structural component of tissue, the extracellular matrix (ECM), is cleared through macrophages. A lack of structural support in this region prevents the invasion of endogenous cells to replace lost tissue, including axonal regrowth. Providing a scaffold within the cavity hence can provide a means for de novo tissue to form. This may be of particular value when targeting larger ischemic or hemorrhagic lesions. However, to fill the tissue cavity completely with biomaterial, superfluous extracellular fluid needs to be drained simultaneously during the injection process.31

To harness the endogenous response, an inductive material that induces structural remodeling of the scaffold is required. ECM is widely used to promote soft tissue repair. Although brain ECM can be formulated as a hydrogel, urinary bladder ECM is more abundant while inducing greater neuronal differentiation and neurite extensions at therapeutically relevant concentrations.32 Implantation of ECM hydrogel into the stroke-damaged brain induces a strong endogenous response of cells, including neuronal progenitors.33 Axonal regrowth can also be promoted using anisotropic scaffolds. Glial scarring surrounding the stroke cavity is hence not an insurmountable barrier to tissue regeneration in the brain and neural progenitors can respond to cues beyond the tissue border.

However, long-term remodeling of the implanted hydrogel and its potential to support functional neuronal network restoration remains unknown.34 In the absence of regional cues providing positional specification of invading cells, topological encoding of guidance and specification cues will need to be delivered to form site-appropriate de novo tissue 35. Vascularization and formation of functional synapses will require additional strategies if this new tissue is to support behavioral functions.5 It is also unclear if principles developed in small rodent models will eventually translate to larger brains.

Large animal models in biomaterial assessments

Targeted, individual administration of biomaterials and/or cells is feasible in large animals as stereotaxic techniques are established, and related brain atlases were published for relevant species.36 Precision is higher than in comparable rodent models, which also allows targeting microlesions more precisely. Moreover, the intervention can be tailored to lesion confirmation, for instance using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based lesion cartography in each individual subject.37 Similar to rodents, large animal species can exhibit significant differences to the human immune system, requiring careful configuration of immunosuppression protocols where needed.38

Component 3: Application of experimental neurorehabilitation

Neurorehabilitation fosters adaptive brain plasticity following stroke, including circuit reorganization39 and activation of endogenous stem cell reservoirs. Recent data suggests that both migration and survival of newborn cells from the subventricular zone can be enhanced by forced limb use even in aged subjects.40 In addition, neurogenesis in the perilesional cortex is involved in motor map reorganization and improved behavioral performance induced by skilled forelimb training, and causality between neurogenesis and functional recovery was proven. In turn, lack of physical activity limits endogenous cell-based repair mechanisms after stroke.41

Although maladaptation can occur if inappropriate task integration is provided40, neurorehabilitation is a promising restoration-supporting strategy after stroke. However, rehabilitation is rarely included in experimental settings, perhaps because of a complex study design and methodological uncertainties. Indeed, rehabilitative training is fundamentally different in rodents and stroke patients. For instance, a therapist kindly guides and assists patients while training of rodents is based on testing apparatus, reward and/or aversive stimuli, which may at worst impose extra stress and mask treatment effects. Speed and completeness of spontaneous recovery in stroke rodents differ compared to that in stroke patients.42 Hence, selection of the appropriate experimental rehabilitation therapy is important.

Mimicking neurorehabilitation in animal models

Various approaches such as voluntary or forced physical training, special rehabilitative training devices, forced use of a forelimb, skilled reaching task, and acrobatic training have been introduced.43 Housing in an enriched environment, resembling the more diverse patient environment during rehabilitation, has been used to provide multiple sensory, motor, social, and visual stimuli, and to support exogenous cell grafts.44 Miniature robotic and electrical devices enable intensive, controllable, and repeatable training approaches in rodents.45,46 The table summarizes experimental neurorehabilitation protocols and stroke model settings in which have been applied successfully.

Ranking of training strategies is challenging given the variety of approaches, experimental models, and outcomes. Recent meta-analyses have addressed this problem. Forced physical training (e.g., treadmill) and skilled forelimb training might be the most effective in stroke animals, while task-oriented motor training seems to generalize to other motor functions. Constraint-induced movement therapy was not efficient in animal models.47

Importantly, rehabilitative and restorative strategies effective in improving motor function are different from those inducing cognitive recovery. Further research should therefore also focus on repair strategies enhancing recovery of cognitive function and common psychological complications such as post-stroke depression.

Combination of neurorehabilitation strategies

Individual neurorehabilitative paradigms can be combined to improve outcome and tissue restoration. Rehabilitative training of the impaired forelimb together with environmental stimulation both increased dentate neurogenesis in rats subjected to cortical infarcts, correlating with improved water-maze performance.48 Combining enriched environment with running wheel training increases survival of transplanted cells.59 Constraint-induced movement therapy enhanced functional recovery, dendritic arborization, and neuronal plasticity in a rat model of ICH, while forced impaired limb use starting one day after ICH led to better functional recovery, restoration of forelimb representation in the motor cortex, and axonal sprouting.57

Timing of neurorehabilitation

Timing of rehabilitative training is critical. There seems to be a therapeutic time window for neurorehabilitative training. Early training (24h) may exacerbate brain damage after focal brain ischemia in rats possibly through excitotoxic mechanisms.60 Such mechanisms may also affect cell-based restorative attempts in the subacute stage. However, post-stroke brain displays increased sensitivity to rehabilitative experience in early chronic stages after stroke (5-14 d), which declines with time.61 This was confirmed in rats being trained in a reaching task starting 4 or 25 days post-lesion.58 Reaching performance improved only in the early training group. Recent meta-analysis is in line with this showing reduced infarct volume and improved cognitive and motor functions, when training is initiated between days 1 to 5 after stroke. Similarly, rehabilitation started between 1 and 7 days after hemorrhagic stroke enhanced functional recovery and plasticity.50 There is no clear relationship between treatment frequency and treatment effects, but improved performance by training is lost if the training is suspended.62

Large animal models and neurorehabilitation

Functional readout protocols are established for large animal species ranging from simple scoring systems63 to highly sophisticated cognitive20 and fine motor/sensor tests.64 A potential problem in using large animal models for assessing functional endpoints is the higher variability as compared to rodents. Although this reflects the situation seen in human stroke patients, it limits study power. Applying neurorehabilitation treatment also requires highly specialized equipment and experimenters. This can be critical due to higher experimental costs and thus lower sample sizes are common.65 Hence, assessing the functional impact of complex neurorehabilitation strategies is not a primary domain of large animal models.It should be limited to confirmative studies when an effect was clearly observed in rodent models. However, large animal models feature larger brains and can therefore be used to indirectly demonstrate neurorehabilitation effects, for instance using structural, functional and/or diffusion tensor imaging. MRI may even be combined with non-invasive assessment of brain metabolism using positron emission tomography.66

Component 4: Supportive pharmacotherapy

It is well known that various drugs, growth factors and bioactive molecules positively influence post-stroke neurogenesis, repair and plasticity processes. A tempting idea therefore is to combine strategies supporting restoration and regeneration with pharmacological interventions for additive or synergistic benefits.67 Complement C3a stimulates neurogenesis and controls neural progenitor migration, accelerating functional recovery when applied intranasally in stroke mice.68 Fluoxetine, a serotonin uptake inhibitor, showed efficacy in human stroke patients.69 Recent approaches include noncoding RNAs including microRNA67, cell-derived bioactive microvesicles70, and antibodies such as anti-Nogo-A.

However, sequence of the different therapies is crucial. For instance, wrong temporal combination of a cell-therapeutic approach and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induced detrimental effects.71 The same holds true for plasticity-enhancing approaches: sequential therapy with first anti-Nogo-A and then skilled forelimb training resulted in enhanced recovery.72 Concurrent application was not effective, suggesting that postlesionally formed connections should first be stabilized before plasticity is enhanced further.73 While pharmacological measures can be applied after ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, and in all species, potential species-specific pharmacodynamics and -kinetics should be taken into consideration. A great advantage of the pharmacological approach is that it can be easily combined with hydrogel applications allowing controlled spatial and temporal release from within the brain.74

Recommendations for a translational roadmap

Common rodent stroke models are homogenous in stroke outcome, fostering the investigation of therapeutic approaches using relatively low sample sizes. However, they insufficiently reflect patient heterogeneity regarding age, sex, comorbidity, and confounding co-medication.8 While it may be scientifically valuable to mirror the complexity and diversity of human stroke in animal models, it stresses development time lines and resources to a critical level, and does not provide an obvious advantage for the investigation of basic principles of tissue repair approaches. An alternative strategy is to enhance specificity of the translational strategy by targeting restoration-permissive lesion configurations (Figure 2).

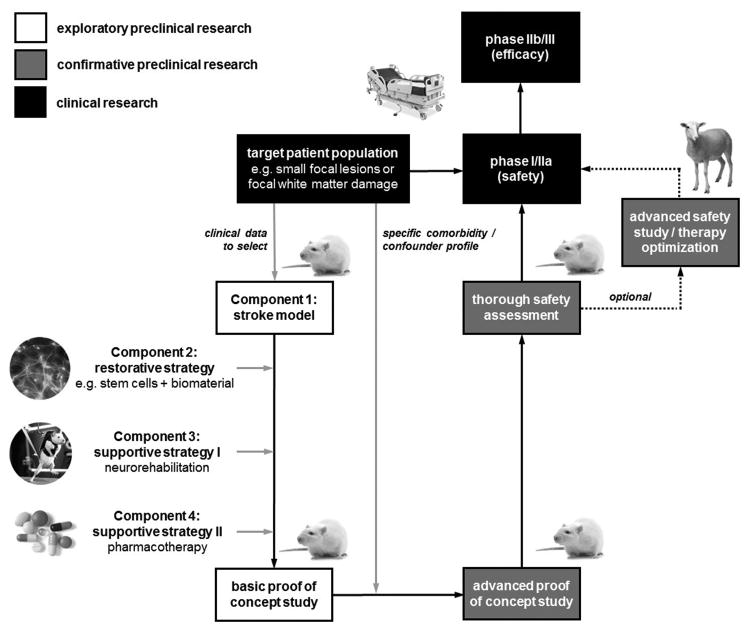

Figure 2. Research strategy draft for clinical translation of tissue restoration in stroke.

After identification of the target patient population, a stroke model well reflecting this population is selected. The tissue restoration strategy, ideally combined with a supportive strategy, is then applied to this model in a basic (exploratory) efficacy trial. In the second step, the typical comorbidity and confounder profile of the target patient population is simulated in the stroke model for an advanced (confirmative) efficacy test, which should also include a thorough safety endpoint. If required, large animal modeling can be used for advanced safety assessments or therapy optimization before moving on to clinical investigations.

In this scenario, an animal model reflecting selected human patient populations is chosen to test the restorative treatment approach, e.g., the use of stem cells. Next, application of potential supportive measures is decided. For instance, the use of functionalized biomaterials is recommended when targeting larger, single lesions cavities as seen after ICH or focal ischemia, but may be of limited use when addressing diffuse tissue damage. In turn, neurorehabilitation and pharmacological support may be particularly efficient in the latter since the ECM and other structural cues fostering cell replacement are preserved to some extent.

Timing of supportive measure application is also critical. For instance, benefit of neurorehabilitation and pharmacological support of neurogenesis and plasticity is limited to a subacute time window, while application of functionalized biomaterials may be most efficient after lesion maturation in the chronic stage. The combination of both approaches must therefore be carefully planned considering the particular lesion type. Proving an additional benefit of double or even triple restoration-supportive strategies is also challenging statistically.

If the efficacy of a tissue-restorative paradigm was explored and proven, subsequent confirmative experiments challenging the paradigm can be limited to comorbidities and confounders in patients presenting the target lesions. Confirmative research should also address safety. For instance, a successful restoration strategy may require transplantation of biomaterials with or without cellular components into the lesioned brain, but multiple stereotaxic transplantations can be a safety issue.75 Large animal models are suitable to simulate repeated transplantation, provide benefits regarding transplantation accuracy, or individualized therapeutic approaches. Sophisticated imaging protocols and detailed histological assessments may partly compensate for smaller sample sizes. Investigating these elements in large animal models can also help in clinical trial design.

A general limitation of the proposed strategy is that not all stroke patients benefit equally from emerging developments, and clinical trial study populations must be carefully selected. On the other hand, treating every patient with the same strategy is unlikely to be successful, so selection of patient populations being sensitive to a restorative therapy is a valid strategy. A similar concept, i.e. selecting patients with a salvageable penumbra prior to thrombectomy, has contributed to the recent success of mechanical recanalization.76 Knowledge gained from successful tissue restoration experiments may also inform neighboring research and disease areas in need of true cerebral tissue restoration including myelodegenerative diseases and storage disorders, or diseases involving loss of selected neuronal populations such as Parkinson's disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Table. Experimental neurorehabilitation, endogenous neurogenesis and behavioral outcome in stroke animals.

| Rehabilitation paradigm | Model | Training | Lesion size | Neurogenesis | Outcome | Comments | Reference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Onset | Intensity | Duration | SVZ | DG | perilesional | sensorimotor | cognitive | |||||

| Enriched environment | photothrombosis | EE+skilled forelimb training | 24h | 50-100 pellets/d | 42d | +/− | + | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | + (water maze) | [48] | |

| tMCAO | EE+atipamezole | 48h | Atipamezole 1mg/kg/d | 10d | +/ − | +/ − (28d) | n.a. | n.a. | Transient improvement (sticky label test) | n.a. | No correlation between neurogenesis and behavior | [49] | |

| Collagenase in striatum | EE+skilled reach training | 7d | 2x/daily for 5d/week | 2w | +/ − | +/ − (32 days) | n.a. | +/ − (32 days) | + skilled reaching test + walking ability +/− cylinder test | n.a. | Enhanced dendritic complexity following rehab | [50] | |

| Voluntary exercise | tMCAO | Running wheel versus swimming | 7d | swimming 2x1min/d | 42d | n.a. | n.a. | Increased cell survival (49d) | n.a. | n.a. | + (water maze in running group) | Upregulation of CREB signaling | [51] |

| ET-1 | Activity box+task-specific training | 3d | 30min/d | 30d | n.a. | + (30d) | n.a. | n.a. | + (forelimb placing) +/− (Montaya stair case) +/− (ladder rung) | n.a. | Perilesional, BDNF-expressing cells | [52] | |

| Forced exercise | tMCAO | treadmill | 2d | 20m/min, 30min/d | 7 or 28d | − (7d) | n.a. | + (7d) | + (7 and 28d) | + (Longa score) | n.a. | Involvement of caveolin-1/VEGF pathway | [53] |

| tMCAO | Rotarod | 3d | 12m/min, 40min/d | 14d | +/ − | + (17d) | + (17d) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [54] | ||

| CIMT | ET-1 | plast | 7d | permanent | 3w | +/ − | n.a. | +/ − | n.a. | + (tapered ledged beam) | n.a. | aged rats | [39] |

| ET-1 | plast | 7d | permanent | 3w | +/ − | + (33d) | + (33d) | + (tapered ledged beam) | + (water mate) | [55] | |||

| Collagenase in globuspallidus | plast | 1 vs. 17d | permanent | 7d | +/ − | n.a. | n.a. | + (in early group) | + (skilled reaching test) + (ladder stepping test) | n.a. | [56] | ||

| Forced limb use | Collagenase in internalcapsule | +intracorticalmicrostimulation | 1d | permanent | 7d | +/ − | n.a. | n.a. | + | + (skilled reaching test) + (ladder stepping test) | n.a. | [57] | |

| Skilled training | photothrombosis | single pellet reaching | 4d | 2 sessions/5d/1w | 4w | +/ − | + (28d) | n.a | n.a | + (single pellet reaching) | n.a. | Motor map reorganization | [58] |

BDNF=brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CIMT=constraint-induced movement therapy; DG=dentate gyrus; EE=enriched environment; ET-1=endothelin-1; ICH=intracerebral hemorrhage; SVZ=subventricular zone; tMCAO=transient middle cerebral artery occlusion; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor; (+)=increased/improved; (+/−)=unaffected; (−)=reduced; n/a=not available/addressed

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Janowski M, Wagner DC, Boltze J. Stem Cell-Based Tissue Replacement After Stroke: Factual Necessity or Notorious Fiction? Stroke. 2015;46:2354–2363. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andres RH, Horie N, Slikker W, Keren-Gill H, Zhan K, Sun G, et al. Human neural stem cells enhance structural plasticity and axonal transport in the ischaemic brain. Brain. 2011;134:1777–1789. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalladka D, Sinden J, Pollock K, Haig C, McLean J, Smith W, et al. Human neural stem cells in patients with chronic ischaemic stroke (PISCES): a phase 1, first-in-man study. Lancet. 2016;388:787–796. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30513-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanai N, Nguyen T, Ihrie RA, Mirzadeh Z, Tsai HH, Wong M, et al. Corridors of migrating neurons in the human brain and their decline during infancy. Nature. 2011;478:382–386. doi: 10.1038/nature10487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dihné M, Hartung HP, Seitz RJ. Restoring neuronal function after stroke by cell replacement: anatomic and functional considerations. Stroke. 2011;42:2342–2350. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bühnemann C, Scholz A, Bernreuther C, Malik CY, Braun H, Schachner M, et al. Neuronal differentiation of transplanted embryonic stem cell-derived precursors in stroke lesions of adult rats. Brain. 2006;129:3238–3248. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter GM, Marlborough FJ, Wardlaw JM. Wide variation in definition, detection, and description of lacunar lesions on imaging. Stroke. 2011;42:359–366. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.594754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boltze J, Nitzsche F, Jolkkonen J, Weise G, Pösel C, Nitzsche B, et al. Concise Review: Increasing the Validity of Cerebrovascular Disease Models and Experimental Methods for Translational Stem Cell Research. Stem Cells. 2017;35:1141–1153. doi: 10.1002/stem.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sozmen EG, Hinman JD, Carmichael ST. Models that matter: white matter stroke models. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser D, Weise G, Möller K, Scheibe J, Pösel C, Baasch S, et al. Spontaneous white matter damage, cognitive decline and neuroinflammation in middle-aged hypertensive rats: an animal model of early-stage cerebral small vessel disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:169. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0169-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sozmen EG, Rosenzweig S, Llorente IL, DiTullio DJ, Machnicki M, Vinters HV, et al. Nogo receptor blockade overcomes remyelination failure after white matter stroke and stimulates functional recovery in aged mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E8453–E8462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615322113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blasi F, Wei Y, Balkaya M, Tikka S, Mandeville JB, Waeber C, et al. Recognition memory impairments after subcortical white matter stroke in mice. Stroke. 2014;45:1468–1473. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ono H, Imai H, Miyawaki S, Nakatomi H, Saito N. Rat white matter injury model induced by endothelin-1 injection: technical modification and pathological evaluation. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2016;76:212–224. doi: 10.21307/ane-2017-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaherty ML. Anticoagulant-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:565–572. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1268866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zille M, Karuppagounder SS, Chen Y, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Finger J, et al. Neuronal Death After Hemorrhagic Stroke In Vitro and In Vivo Shares Features of Ferroptosis and Necroptosis. Stroke. 2017;48:1033–1043. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamori Y, Horie R, Handa H, Sato M, Fukase M. Pathogenetic similarity of strokes in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats and humans. Stroke. 1976;7:46–53. doi: 10.1161/01.str.7.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iida S, Baumbach GL, Lavoie JL, Faraci FM, Sigmund CD, Heistad DD. Spontaneous stroke in a genetic model of hypertension in mice. Stroke. 36:1253–1258. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000167694.58419.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher M, Vasilevko V, Passos GF, Ventura C, Quiring D, Cribbs DH. Therapeutic modulation of cerebral microhemorrhage in a mouse model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2011;42:3300–3303. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A, Ikram MA, Wielopolski PA, Niessen WJ, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2008;70:1208–1214. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000307750.41970.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hainsworth AH, Allan SM, Boltze J, Cunningham C, Farris C, Head E, et al. Translational models for vascular cognitive impairment: a review including larger species. BMC Med. 2017;15:16. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0793-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey EL, McCulloch J, Sudlow C, Wardlaw JM. Potential animal models of lacunar stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40:e451–458. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie Q, Gu Y, Hua Y, Liu W, Keep RF, Xi G. Deferoxamine attenuates white matter injury in a piglet intracerebral hemorrhage model. Stroke. 2014;45:290–292. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan SJ, Lee FY, Cheung MM, Ding AY, Yang J, Ma SJ, et al. Bilateral substantia nigra and pyramidal tract changes following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: an MR diffusion tensor imaging study. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1089–1095. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barratt HE, Lanman TA, Carmichael ST. Mouse intracerebral hemorrhage models produce different degrees of initial and delayed damage, axonal sprouting, and recovery. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1463–1471. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao S, Zheng M, Hua Y, Chen G, Keep RF, Xi G. Hematoma Changes During Clot Resolution After Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2016;47:1626–1631. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziemba AM, Gilbert RJ. Biomaterials for Local, Controlled Drug Delivery to the Injured Spinal Cord. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:245. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bible E, Chau DY, Alexander MR, Price J, Shakesheff KM, Modo M. Attachment of stem cells to scaffold particles for intra-cerebral transplantation. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1440–1453. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bible E, Qutachi O, Chau DY, Alexander MR, Shakesheff KM, Modo M. Neo-vascularization of the stroke cavity by implantation of human neural stem cells on VEGF-releasing PLGA microparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7435–7446. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Y, Wang J, Shi Y, Pu H, Leak RK, Liou AK, et al. Implantation of Brain-derived Extracellular Matrix Enhances Neurological Recovery after Traumatic Brain Injury. Cell Transplant. 2016;26:1224–1234. doi: 10.1177/0963689717714090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooke MJ, Wang Y, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Controlled epi-cortical delivery of epidermal growth factor for the stimulation of endogenous neural stem cell proliferation in stroke-injured brain. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5688–5697. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massensini AR, Ghuman H, Saldin LT, Medberry CJ, Keane TJ, Nicholls FJ, et al. Concentration-dependent rheological properties of ECM hydrogel for intracerebral delivery to a stroke cavity. Acta Biomater. 2015;27:116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medberry CJ, Crapo PM, Siu BF, Carruthers CA, Wolf MT, Nagarkar SP, et al. Hydrogels derived from central nervous system extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 2013;34:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghuman H, Massensini AR, Donnelly J, Kim SM, Medberry CJ, Badylak SF, et al. ECM hydrogel for the treatment of stroke: Characterization of the host cell infiltrate. Biomaterials. 2016;91:166–181. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghuman H, Gerwig M, Nicholls FJ, Liu JR, Donnelly J, Badylak SF, et al. Long-term retention of ECM hydrogel after implantation into a sub-acute stroke cavity reduces lesion volume. Acta Biomater. 2017;63:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vazin T, Ashton RS, Conway A, Rode NA, Lee SM, Bravo V, et al. The effect of multivalent Sonic hedgehog on differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into dopaminergic and GABAergic neurons. Biomaterials. 2014;35:941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nitzsche B, Frey S, Collins LD, Seeger J, Lobsien D, Dreyer A, et al. A stereotaxic, population-averaged T1w ovine brain atlas including cerebral morphology and tissue volumes. Front Neuroanat. 2015;9:69. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modo M, Crum WR, Gerwig M, Vernon AC, Patel P, Jackson MJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and tensor-based morphometry in the MPTP non-human primate model of Parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diehl R, Ferrara F, Müller C, Dreyer AY, McLeod DD, Fricke S, et al. Immunosuppression for in vivo research: state-of-the-art protocols and experimental approaches. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:146–179. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng X, Sun L, Yin D, Jia J, Zhao Z, Jiang Y, et al. The plasticity of intrinsic functional connectivity patterns associated with rehabilitation intervention in chronic stroke patients. Neuroradiology. 2016;58:417–427. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu HL, Zhao M, Zhao SS, Xiao T, Song CG, Cao YP, et al. Forced limb-use enhanced neurogenesis and behavioral recovery after stroke in the aged rats. Neuroscience. 2015;286:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasuhara T, Hara K, Maki M, Matsukawa N, Fujino H, Date I, et al. Lack of exercise, via hindlimb suspension, impedes endogenous neurogenesis. Neuroscience. 2007;149:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jolkkonen J, Kwakkel G. Translational Hurdles in Stroke Recovery Studies. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0461-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao S, Zhao M, Xiao T, Jolkkonen J, Zhao C. Constraint-induced movement therapy overcomes the intrinsic axonal growth-inhibitory signals in stroke rats. Stroke. 2013;44:1698–1705. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hicks AU, Lappalainen RS, Narkilahti S, Suuronen R, Corbett D, Sivenius J, et al. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursor cells and enriched environment after cortical stroke in rats: cell survival and functional recovery. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:562–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vigaru B, Lambercy O, Graber L, Fluit R, Wespe P, Schubring-Giese M, et al. A small-scale robotic manipulandum for motor training in stroke rats. IEEE Int Conf Rehabil Robot. 2011;2011:5975349. doi: 10.1109/ICORR.2011.5975349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spalletti C, Lai S, Mainardi M, Panarese A, Ghionzoli A, Alia C, et al. A robotic system for quantitative assessment and poststroke training of forelimb retraction in mice. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;28:188–196. doi: 10.1177/1545968313506520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janssen H, Speare S, Spratt NJ, Sena ES, Ada L, Hannan AJ, et al. J Exploring the efficacy of constraint in animal models of stroke: meta-analysis and systematic review of the current evidence. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27:3–12. doi: 10.1177/1545968312449696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wurm F, Keiner S, Kunze A, Witte OW, Redecker C. Effects of skilled forelimb training on hippocampal neurogenesis and spatial learning after focal cortical infarcts in the adult rat brain. Stroke. 2007;38:2833–2840. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.485524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuptsova K, Kvist E, Nitzsche F, Jolkkonen J. Combined enriched environment÷atipamezole treatment transiently improves sensory functions in stroke rats independent from neurogenesis and angiogenesis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Auriat AM, Wowk S, Colbourne F. Rehabilitation after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats improves recovery with enhanced dendritic complexity but no effect on cell proliferation. Behav Brain Res. 2010;214:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luo CX, Jiang J, Zhou QG, Zhu XJ, Wang W, Zhang ZJ, et al. Voluntary exercise-induced neurogenesis in the postischemic dentate gyrus is associated with spatial memory recovery from stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1637–1646. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Livingston-Thomas JM, McGuire EP, Doucette TA, Tasker RA. Voluntary forced use of the impaired limb following stroke facilitates functional recovery in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2014;261:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pang Q, Zhang H, Chen Z, Wu Y, Bai M, Liu Y, et al. Role of caveolin-1/vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in basic fibroblast growth factor-induced angiogenesis and neurogenesis after treadmill training following focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2017;1663:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee SH, Kim YH, Kim YJ, Yoon BW. Enforced physical training promotes neurogenesis in the subgranular zone after focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurol Sci. 2008;269:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao S, Qu H, Zhao Y, Xiao T, Zhao M, Li Y, et al. CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 reverses the neurogenesis and behavioral recovery promoted by forced limb-use in stroke rats. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2015;33:809–821. doi: 10.3233/RNN-150515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishida A, Misumi S, Ueda Y, Shimizu Y, Cha-Gyun J, Tamakoshi K, et al. Early constraint-induced movement therapy promotes functional recovery and neuronal plasticity in a subcortical hemorrhage model rat. Behav Brain Res. 2015;284:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishida A, Isa K, Umeda T, Kobayashi K, Kobayashi K, Hida H, et al. Causal Link between the Cortico-Rubral Pathway and Functional Recovery through Forced Impaired Limb Use in Rats with Stroke. J Neurosci. 2016;36:455–467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2399-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shiromoto T, Okabe N, Lu F, Maruyama-Nakamura E, Himi N, Narita K, et al. The Role of Endogenous Neurogenesis in Functional Recovery and Motor Map Reorganization Induced by Rehabilitative Therapy after Stroke in Rats. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hicks AU, Hewlett K, Windle V, Chernenko G, Ploughman M, Jolkkonen J, et al. Enriched environment enhances transplanted subventricular zone stem cell migration and functional recovery after stroke. Neuroscience. 2007;146:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Risedal A, Nordborg C, Johansson BB. Infarct volume and functional outcome after pre- and postoperative administration of metyrapone, a steroid synthesis inhibitor, in focal brain ischemia in the rat. Eur J Neurol. 1999;6:481–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.1999.640481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biernaskie J, Chernenko G, Corbett D. Efficacy of rehabilitative experience declines with time after focal ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1245–1254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3834-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bell JA, Wolke ML, Ortez RC, Jones TA, Kerr AL. Training Intensity Affects Motor Rehabilitation Efficacy Following Unilateral Ischemic Insult of the Sensorimotor Cortex in C57BL/6 Mice. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29:590–598. doi: 10.1177/1545968314553031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boltze J, Förschler A, Nitzsche B, Waldmin D, Hoffmann A, Boltze CM, et al. Permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in sheep: a novel large animal model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1951–1964. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McEntire CR, Choudhury GR, Torres A, Steinberg GK, Redmond DE, Jr, Daadi MM. Impaired Arm Function and Finger Dexterity in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Stroke: Motor and Cognitive Assessments. Stroke. 2016;47:1109–1116. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balkaya MG, Trueman RC, Boltze J, Corbett D, Jolkkonen J. Behavioral outcome measures to improve experimental stroke research [published online ahead of print July 29, 2017] [Accessed December 12, 2017];Behav Brain Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.07.039. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166432817307325?via%3Dihub. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Werner P, Saur D, Zeisig V, Ettrich B, Patt M, Sattler B, et al. Simultaneous PET/MRI in stroke: a case series. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:1421–1425. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sommer CJ, Schäbitz WR. Fostering Poststroke Recovery: Towards Combination Treatments. Stroke. 2017;48:1112–1119. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stokowska A, Atkins AL, Morán J, Pekny T, Bulmer L, Pascoe MC, et al. Complement peptide C3a stimulates neural plasticity after experimental brain ischaemia. Brain. 2017;140:353–369. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chollet F, Tardy J, Albucher JF, Thalamas C, Berard E, Lamy C, et al. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:123–130. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doeppner TR, Herz J, Görgens A, Schlechter J, Ludwig AK, Radtke S, et al. Extracellular Vesicles Improve Post-Stroke Neuroregeneration and Prevent Postischemic Immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1131–1143. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pösel C, Scheibe J, Kranz A, Bothe V, Quente E, Fröhlich W, et al. Bone marrow cell transplantation time-dependently abolishes efficacy of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after stroke in hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2014;45:2431–2437. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wahl AS, Omlor W, Rubio JC, Chen JL, Zheng H, Schröter A, et al. Neuronal repair. Asynchronous therapy restores motor control by rewiring of the rat corticospinal tract after stroke. Science. 2014;344:1250–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1253050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wahl AS, Schwab ME. Finding an optimal rehabilitation paradigm after stroke: enhancing fiber growth and training of the brain at the right moment. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:381. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cook DJ, Nguyen C, Chun HN, L Llorente I, Chiu AS, Machnicki M, et al. Hydrogel-delivered brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes tissue repair and recovery after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:1030–1045. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16649964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boltze J, Arnold A, Walczak P, Jolkkonen J, Cui L, Wagner DC. The Dark Side of the Force - Constraints and Complications of Cell Therapies for Stroke. Front Neurol. 2015;6:155. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khandelwal P, Yavagal DR, Sacco RL. Acute Ischemic Stroke Intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2631–2644. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]