Abstract

Heavy cannabis use is associated with a wide array of physical, mental and functional problems. Therefore, cannabis use disorders (CUDs) may be a major public health concern. Given the adverse health consequences of CUDs, the present study seeks to find possible precursors of CUDs. The current study consisted of five waves of data collection from the Harlem Longitudinal Development Study. Among 816 participants, about half are African Americans (52%), and the other half are Puerto Ricans (48%). We used Mplus to obtain the triple trajectories of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms. Logistic regression analyses were then conducted to examine the associations between the trajectory groups and CUDs. The five trajectory groups were: 1) Moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms (MHH;12%); 2) Moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms (MHL;26%); 3) Moderate alcohol use, low tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms (MLL; 18%); 4) Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms (LNH; 11%); and 5) Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms (LNL; 33%). The MHH, MHL, MLL, and LNH trajectory groups were associated with an increased likelihood of having CUDs compared to the LNL trajectory group after controlling for a number of confounding factors (e.g., CUDs in the late twenties). The findings of the current longitudinal study suggest that treatments designed to reduce or quit drinking as well as smoking, and to relieve depressive symptoms may reduce the prevalence of CUDs.

Keywords: Cannabis use disorders, alcohol use, tobacco use, depressive symptoms, trajectory analysis

INTRODUCTION

Cannabis use disorders (CUDs) are a major public health concern. It is estimated that 3.9% and 8.3% of emerging/young adults in the United States (US) have a lifetime diagnosis of cannabis abuse and dependence, respectively (Haberstick et al., 2014). Although cannabis use is often perceived as benign (Caldicott, Holmes, Roberts-Thomson, & Mahar, 2005; Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, 2014), research has demonstrated that heavy cannabis use is associated with a wide array of physical, mental and functional problems such as respiratory (Owen, Sutter, & Albertson, 2014), cardiovascular (Barbieux, Veran, & Detante, 2012; Wolff et al., 2013), brain morphology (Rigucci et al., 2016), cognitive impairment (Auer et al., 2016; Hooper, Woolley, & De Bellis, 2014), mood disorders (Bovasso, 2001), psychosis in susceptible individuals (Bagot, Milin, & Kaminer, 2015; Karila et al., 2014; Volkow et al., 2014), academic failure (Brook, Stimmel, Zhang, & Brook, 2008; Homel, Thompson, & Leadbeater, 2014; Volkow et al., 2014), and driving accidents (Karila et al., 2014).

The National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions reported a significant increase in the prevalence of CUD between 1991–1992 and 2001–2002 among African Americans (0.8% vs. 1.8%) and Hispanic Americans (0.6% vs. 1.2%) (Compton, Grant, Colliver, Glantz, & Stinson, 2004). More recently, even the higher prevalence of CUDs among African Americans (2.4%) and Hispanic Americans (1.3%) was reported in 2013 (Wu, Zhu, & Swartz, 2016). Furthermore, past-year prevalence of cannabis abuse and dependence among past-year adult cannabis users aged >18 years for African Americans (17%) and for Hispanic Americans (13%) are higher than for European Americans (10%) (Wu et al., 2016). Given the public health concerns about CUDs and susceptibility to developing CUDs among African American and Hispanic adults, the current study seeks to examine the possible long-term predictors of CUDs using a sample of African Americans and Puerto Ricans.

The findings of prior studies have suggested that legal substance use such as alcohol has been implicated in later CUDs using a sample of African American and Hispanic participants (Brook, Lee, Finch, Koppel, & Brook, 2011; Lee, Brook, De La Rosa, Kim, & Brook, 2017). Although a number of individuals in their late twenties “mature out” of heavy alcohol use upon successful transitions to adult roles (e.g., career and family)(Bachman, Wadsworth, O'Malley, Johnston, & Schulenberg, 1997; Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002), there are still many African American and Hispanic American individuals who continue to fail to moderate their alcohol consumption (Lee et al., 2017). This can have long-term effects on physical and psychological well-being as well as on the development of CUDs (Schulenberg, Maggs, & O’Malley, 2003).

Nicotine dependence, which could have resulted from tobacco use, has been also found to be related to CUDs among African Americans and Puerto Ricans (Brook, Lee, Finch, et al., 2011). In support, this research team using the same sample of African Americans and Puerto Ricans reported that the number of chronic marijuana users among the chronic smokers are significantly greater than would be expected under independence (Brook, Lee, Finch, & Brown, 2010). A number of individuals who drink alcohol or smoke cigarettes are at risk for the use of other substances (Van Skike et al., 2016). Heffner and colleagues reported that cigarette smoking was related to co-occurring alcohol use and cannabis use disorders (Heffner et al., 2012). On the other hand, cannabis use is associated with tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence as noted by several investigators (Brook, Lee, & Brook, 2015; Patton, Coffey, Carlin, Sawyer, & Lynskey, 2005).

In addition, depressive symptoms have been found to be associated with CUDs (Curry et al., 2012). Among the several theories of patterns of comorbidity between emotional disorders and substance use disorders, the “self-medication” hypothesis suggests that individuals with emotional dysregulation use substances to alleviate distress (Kushner, Sher, & Beitman, 1990; Smith & Book, 2010). In support, epidemiological and cross-sectional studies have reported elevated prevalence of substance use disorders among individuals with depressive mood (Conway, Compton, Stinson, & Grant, 2006; Kessler et al., 2005). However, little research has examined the longitudinal relationship of depression and CUDs, and none of these studies, to our knowledge, have assessed trajectories of depressive symptoms with alcohol use and tobacco use simultaneously.

Furthermore, alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms frequently co-occur (Baker et al., 2010; Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2010; Kang & Lee, 2010), although most research has examined the co-morbidity of clinical disorders (Morozova, Rabin, & George, 2015) rather than subsyndromal conditions, e.g., depressive symptoms and alcohol use (Grant et al., 2015). African American and Hispanic young adults who use substances report their depressive symptoms (Brook, Lee, Brown, Finch, & Brook, 2011; Goodwin, Zvolensky, Keyes, & Hasin, 2012). Also, a study based on a sample of 505 African American men reported that substance use forecast increases in depressive symptoms (Kogan, Cho, Oshri, & Mackillop, 2017). Studies have found bidirectional associations between nicotine dependence and depression (Chaiton, Cohen, O'Loughlin, & Rehm, 2009) as well as between an alcohol use disorder and a depressive disorder (Pacek, Martins, & Crum, 2013).

Among the college students, males as compared to females are more likely to report substance use (e.g., cannabis use) in general (Boyd, 2014). The prevalence of cannabis use among African Americans (4.7%) is higher than among Hispanic Americans (3.3%) (Compton et al., 2004). Several researchers posited that early initiation of cannabis use and regular use during adolescence are particular risk factors for later CUDs (Copeland, Clement, & Swift, 2014). Bachman and colleagues (2013) reported that a higher educational attainment was associated with fewer problems with drug use, such as CUDs. Therefore, we used race/ethnicity, gender, earlier CUDs, and educational level as control variables.

To our knowledge, no studies have identified longitudinal trajectories of concurrent alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms. Moreover, there have been no studies that have examined these triple trajectories as predictors of later CUDs. A greater understanding of comorbid patterns of legal drug use and depressive symptoms over time and their effect on the development of CUDs is important to identify those individuals at greatest risk for CUDs as well as to refer them to prevention programs. The goal of the present study, therefore, is to examine the association of long-term trajectories of concurrent alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms from adolescence to adulthood with CUDs in adulthood.

The hypotheses for the present study are:

Membership in the triple comorbid trajectory group (high levels of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms) will be related to a greater likelihood of CUDs in adulthood than membership in the trajectory group of no alcohol use and no tobacco use without depressive symptoms.

Membership in the dual comorbid trajectory groups, i.e., the alcohol use and tobacco use group, the alcohol use and depressive symptoms group, and the tobacco use and depressive symptoms group, will be associated with a greater likelihood of CUDs than membership in the trajectory group of no alcohol use and no tobacco use without depressive symptoms; and

Membership in the triple comorbid trajectory group will be associated with a greater likelihood of having CUDs in adulthood than membership in any of the dual comorbid trajectory groups.

METHODS

Participants

The present study consisted of five waves of data collection of the Harlem Longitudinal Development Study. About a half of the participants were African Americans (52%), and other half was Puerto Ricans (48%). The study began in 1990 (Time 1; T1) when participants were mean age 14.1 years (SD=1.3 years; N=1,332). Participants were originally recruited from public schools in the East Harlem area of New York City. The second wave of data collection took place in 1994–1996 (Time 2; T2) when participants were mean age 19.2 years (SD=1.5; N=1,190). At Time 3 (T3; 2000–2001), the sample size was reduced (N=662) due to budgetary restrictions, and participants were randomly selected from those who had participated at T2 (mean age= 24.4; SD=1.3). At Time 4 (T4; 2004–2006), participants were mean age 29.2 years (SD=1.4; N=838). Data collection at time 5 (T5) took place in 2007–2010 when participants were mean age 32.3 years (SD=1.3; N=816). At T1, questionnaires were administered in the school classrooms via tape players under the supervision of study staff. (Teachers were not present.) At T2 and T3, participants were interviewed in person or by phone if they had moved far away from New York City. At T4 and T5, participants were mailed questionnaires which they self-administered and returned to us de-identified, i.e., data were identified by the participants study code number. At T1 and T2, parents of participants who were under 18 years of age provided passive consent for their child’s participation in the study. Participants who were 18 years or older (i.e., T3–T5) provided signed informed consent forms. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the New York University School of Medicine approved the study for T4 and T5, and the IRBs of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and New York Medical College approved the study for the earlier waves. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse for T1–T4 and from National Cancer Institute for T5. Additional information regarding the study methodology is available from a previous report (Lee, Brook, Finch, & Brook, 2015).

Measures

Alcohol use (Room, 1990), tobacco use (Kann et al., 2000), and depressive symptoms (Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974) were measured from T1–T4 (mean ages 14 to 29 years). For the measure of depressive symptoms, two item scales at T1–T2 and five item scales at T3-T4 were constructed since we asked the participants about their depressive symptoms using only two items at T1–T2. Table 1 lists the scales, time waves, authors, response ranges, sample items, and Cronbach’s alphas (or inter-item correlation) for the independent variables (alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms) and control variables (gender at T1, race/ethnicity at T1, CUDs at T4, and educational level at T4). (See Table 1.)

Table 1.

Independent and Control Variables: Scales, Time Wave(s), Author(s), Number of Items, Response Range, Sample Item, and Inter-item Correlation (γ) or Cronbach’s Alpha (α)

| Scale | Number of Items | Response Range | Sample Item | γ or α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables: | ||||

| Alcohol use at T1–T4 (Room et al., 1990) | 1 | (0) none at all - (4) 3 or 4 drinks a day or more | “How often did you drink beer, wine, or hard liquor in the past year?” | N/A (Single Item) |

| Tobacco use at T1–T4 (Kann et al., 2000) | 1 | (0) none at all - (4) about one and a half packs a day or more. | “How many cigarettes a day did you smoke in the past year?” | N/A (Single Item) |

| Depressive symptoms at T1–T4 (Derogatis et al., 1974) | 2 at T1, T2 5 at T3, T4 |

(0) completely false - (3) completely true | “Do you sometimes feel: a) unhappy, sad, or depressed?; b) hopeless about the future? at T1, T2, T3, T4; c) cranky or crabby?; d) angry toward people with no reason?; and e) slowing down?” at T3, T4 | γ = 0.47 at T1 (p<.0001) γ = 0.55 at T2 (p<.0001) α = 0.74 at T3, T4 |

|

| ||||

| Control variables: | ||||

| Gender at T1 | 1 | Female=1; Male=2 | N/A | N/A (Single Item) |

| Ethnicity at T1 | 1 | African American=1; Puerto Rican=2 | N/A | N/A (Single Item) |

| CUDs at T4 | 1 | No=0; Yes=1 | Cannabis use abuse or dependence for the past 5 years (for details, see CUDs at 5 in the Measures section) | N/A (Single Item) |

| Educational level at T4 | 1 | (0) 11th grade or below - (6) postgraduate program |

“What is the last year of school you completed?” | N/A (Single Item) |

Cannabis use disorder was assessed at T5 using the criteria used in the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-IV (DSM-IV, 2000). The measure of CUD obtained a score of 1 if a participant was dependent on cannabis use or was a cannabis abuser. Otherwise, CUD obtained a score of 0. Cannabis dependence was ascertained by the presence of 3 or more of the following criteria during the prior 12 months: tolerance, withdrawal, recurrent use to avoid withdrawal symptoms, impaired control over use, unsuccessful cessation, excessive time thinking about or engaging in use, relinquishing of normal activities for use, and continued use despite physical or psychological problems. If the participant did not meet the criteria for cannabis dependence, cannabis abuse was diagnosed by the presence of at least one of the following criteria during the previous 12 months: experiencing the effects or after-effects of the substance at work, at school or during childcare, feeling the substance’s effects or after-effects when one might get hurt (e.g., while driving), legal problems due to the use of the substance, or impaired relations with others because of use of the substance.

Analytic procedure

We used Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) to obtain the three variable trajectories of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms (T1–T4). Alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms at each time point were treated as censored normal variables. We used the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to determine the number of trajectory groups. The observed trajectories for each of the groups consisted of the averages of the Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) for alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms, respectively, at each point in time when the participants were assigned to the group with the largest BPP. We applied the full information maximum likelihood approach for missing data (Muthén & Muthén, 2010).

Logistic regression analyses were then conducted to examine whether the BPP of the triple trajectory group with high levels of all three variables from T1 to T4, compared with the BPPs of each of the other trajectory groups from T1 to T4, were associated with CUDs at T5, controlling for gender at T1, race/ethnicity at T1, CUDs at T4, and educational level at T4.

RESULTS

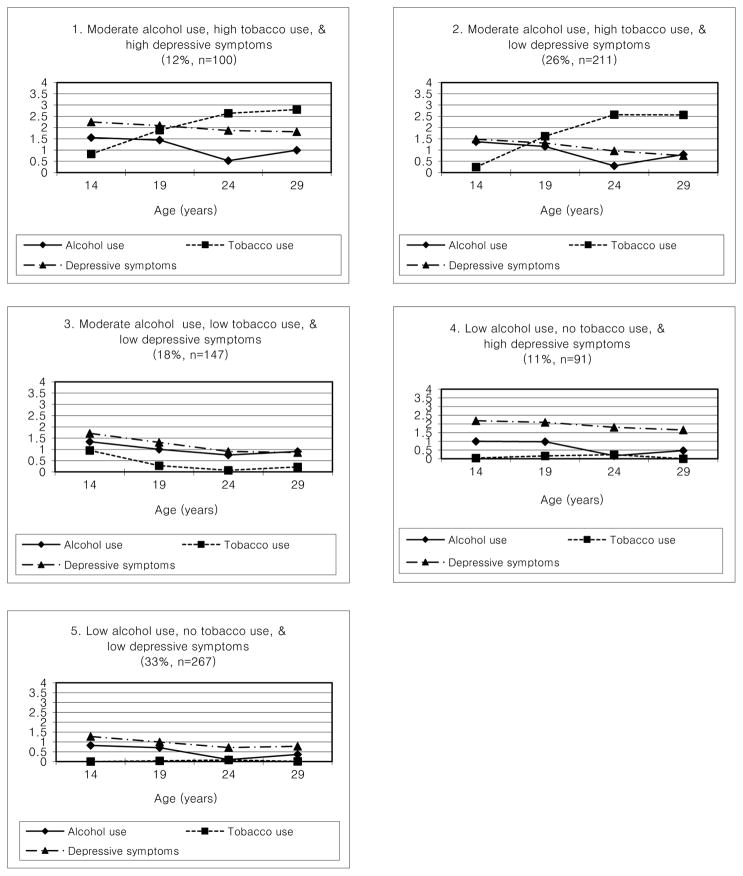

For the triple trajectories, the BICs were 20558, 20465, 20356, 20278, and 20286 for a 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6-group model, respectively. The five group model was selected because it had the smallest BIC score. Figure 1 presents the observed trajectories and the percentages of the sample who were members in each of the five trajectory groups. The mean BPP in each trajectory group ranged from 77% to 87%, which indicated an adequate classification. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Triple trajectories of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms

Notes.

Answer options for alcohol use: (0) none at all - (4) 3 or 4 drinks a day or more;

Answer options for tobacco use: (0) none at all - (4) about one and a half packs a day or more;

Answer options for depressive symptoms: (0) completely false - (3) completely true

The five trajectory groups were: 1) Moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms, which we named MHH (prevalence 12%, mean BPP=87%); 2) Moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms, named MHL (prevalence 26%, mean BPP=87%); 3) Moderate alcohol use, low tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms, named MLL (prevalence 18%, mean BPP=81%); 4) Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms, named LNH (prevalence 11%, mean BPP=77%); and 5) Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms, named LNL (prevalence 33%, mean BPP=84%).

Table 2 presents summary statistics for each of the five trajectory groups. Members in the MHH group drink alcohol once a week to several times a week at ages 14, 19, and 29, but less than once a week at age 24, smoke less than a few cigarettes a week at age 14, a few cigarettes a week at age 19, less than half a pack a day at ages 24 and 29, and have quite high depressive symptoms at each wave. Individuals in the MHL group show similar patterns with the MHH group in terms of alcohol and tobacco use; however, they have low depressive symptoms as compared to those in the MHH group. The pattern of alcohol use of the MLL group is similar to the pattern of the MHL group, but individuals in the MLL group smoke less than a few cigarettes a week at all times, and have low depressive symptoms at all times. Individuals in the LNH group drink alcohol less than once a week in teens, almost no alcohol use in 20s, no tobacco use at ages 14 and 29, almost no tobacco use at ages 19 and 24, but have high depressive symptoms which is similar to the depressive symptoms pattern of the MHH group. Members in the LNL group show almost no alcohol use, no tobacco use, and very low depressive symptoms at all times.

Table 2.

Summary statistics (fractions, means, and standard deviations)

| MHH | MHL | MLL | LNH | LNL | Over all | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (G1; 12%, n=100) | (G2; 26%, n=211) | (G3; 18%, n=147) | (G4; 11%, n=91) | (G5; 33%, n=267) | (N=816) | ||

| CUDs at T5 | 17.0% | 14.7% | 5.4% | 6.6% | 2.6% | 8.5% | |

| Females | 73.0% | 45.5% | 65.3% | 70.3% | 61.1% | 60.3% | |

| African Americans | 34.0% | 45.5% | 57.8% | 50.6% | 61.4% | 52.1% | |

| CUDs at T4 | 39.0% | 23.7% | 13.6% | 16.5% | 2.6% | 16.1% | |

| Educational level at T4 | 1.6 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.8) | 2.7 (1.9) | 2.2 (1.8) | 3.1 (1.9) | 2.5 (1.9) | |

|

| |||||||

| Alcohol use | T1 | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.9) |

| T2 | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.7) | 1.0 (1.0) | 0.7 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.9) | |

| T3 | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.5) | |

| T4 | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.7) | |

|

| |||||||

| Tobacco use | T1 | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.6) | 1.0 (1.0) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.7) |

| T2 | 1.9 (1.7) | 1.6 (1.5) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.3) | 0.7 (1.3) | |

| T3 | 2.6 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.4) | 1.2 (1.6) | |

| T4 | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.3) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.1) | 1.1 (1.5) | |

|

| |||||||

| Depressive symptoms | T1 | 2.2 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.9) |

| T2 | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.9) | |

| T3 | 1.9 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.7) | |

| T4 | 1.8 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.6) | |

Note: CUDs = Cannabis use disorders; MHH = Moderate alcohol use, High tobacco use, and High depressive symptoms; MHL = Moderate alcohol use, High tobacco use, and Low depressive symptoms; MLL = Moderate alcohol use, Low tobacco use, and Low depressive symptoms; LNH = Low alcohol use, No tobacco use, and High depressive symptoms; LNL = Low alcohol use, No tobacco use, and Low depressive symptoms

Table 3 shows the adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for CUDs in the logistic regression analyses. When we compared the trajectory groups, the reference variable in Table 3 is the BPP of the group whose members reported low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms. The higher BPP of the moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms group (AOR=10.61, p <.01) and the moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms group (AOR=5.33, p<.05) were associated with an increased likelihood of having CUDs at T5 compared to the low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms group. Also, the BPP of the moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms group increased the likelihood of having CUDs as compared with the moderate alcohol use, low tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms group (AOR=4.05, p<.05). For the control variables, males as compared with females (AOR=3.99, p<.001) and African Americans as compared with Puerto Ricans (AOR=0.46, p<.05) were more likely to have CUDs at T5. Also, CUDs at T4 was associated with an increased likelihood of having CUDs at T5 (AOR=5.95, p<.001).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of T5 cannabis use disorders (CUDs) from triple trajectories of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms (T1-T4) among African American and Puerto Rican adults

| AOR of CUDs at T5 (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Control variables: | |

| Gender at T1 | 3.99 (2.02, 7.91) *** |

| Race/ethnicity at T1 | 0.46 (0.25, 0.86) * |

| CUDs at T4 | 5.95 (3.21, 11.02) *** |

| Educational level at T4 | 0.98 (0.82, 1.16) |

|

| |

| Triple trajectories at T1–T4: | |

| Moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms vs. Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms | 10.61 (2.51, 44.84) ** |

| Moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms vs. Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms | 5.33 (1.48, 19.19) * |

| Moderate alcohol use, low tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms vs. Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms | 3.33 (0.71, 15.16) |

| Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms vs. Low alcohol use, no tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms | 2.58 (0.41, 16.28) |

| Moderate alcohol use, high tobacco use, and high depressive symptoms vs. Moderate alcohol use, low tobacco use, and low depressive symptoms | 3.18 (1.01, 10.30) * |

Notes.

p<.1,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Males and African Americans coded higher than females and Puerto Ricans, respectively.

N/A= Not Applicable

DISCUSSION

We have examined the developmental course of the use of alcohol, tobacco, and depressive symptoms beginning in adolescence and their association with CUDs in adulthood with a number of control variables such as gender, race/ethnicity, CUDs and educational level in the late twenties.

As we hypothesized, individuals in the MHH group, reported moderate level of alcohol use and high levels of tobacco use as well as depressive symptoms, have a 10 times greater risk for having CUDs as compared with individuals in the LNL group. Also, members in the MHH group have an about 3 times greater risk for having CUDs as compared with members in the MLL group. These findings may imply the fact that the presence of all three variables, i.e., alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms, together during adolescence and young adulthood has some impact on CUDs in adulthood.

Of note is that the MHL group, consisting of members who reported moderate alcohol use and high level of smoking but low depressive symptoms, was highly associated with CUDs as compared with the LNL group. These results are in support of several studies that have found that cigarette smoking predicts cannabis use (Heffner et al., 2012; Hindocha et al., 2015). An intriguing aspect of cannabis and tobacco co-use is that, for both drugs, the predominant route of administration is via inhalation (Agrawal, Budney, & Lynskey, 2012). It is possible that the behavioral routines associated with cigarette smoking, such as lighting and inhaling combustible plant material, translates easily to the use of cannabis.

The association between the MLL group, as compare with the LNL group, and CUDs indicated not significant. People who drink alcohol moderately and smoke 1 or 2 cigarettes a day with low depressive symptoms are not statistically different from individuals in the LNL group. Also, the LNH group, consisting of members who report low levels of drinking and no tobacco use but high depressive symptoms, had no association with CUDs as compared with the LNL group. Given the low alcohol use and no tobacco use, individuals with high depressive symptoms are not different from individuals with low depressive symptoms in terms of having CUDs. These two comparisons also suggest that the presence of all three variables together has an impact on CUDs, since the other studies showed a single effect of alcohol use (Lee et al., 2017) and a single effect of depressive symptoms (Lev-Ran et al., 2014) on CUDs.

As regards covariates, our findings indicating that males are more likely to have CUDs than females are consistent with reports from other investigators (Hasin et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2013). Females may have a less severe form of CUDs because of perceived stigmatization of having a substance use disorder (Toray, Coughlin, Vuchinich, & Patricelli, 1991). It also may be due in part to traditional gender role socialization, that is, males and females experience different pressures to endorse typical male and female behaviors and attitudes reflecting masculinity and femininity. In the US and many other societies, for example, males are encouraged to engage in substance use (Iwamoto, Corbin, Lejuez, & MacPherson, 2014).

The present study also found that African Americans have greater likelihood of having CUDs as compared with Puerto Ricans. This is in accord with the findings from Compton et al. (2004) reporting that past-year prevalence of cannabis use among African Americans (4.7%) is higher than among Hispanic Americans (3.3%). Furthermore, Wu et al. (2016) reported that African Americans who use cannabis are more likely to develop CUDs as compared to Hispanic Americans. Consequently, the racial/ethnic difference in CUDs (African Americans > Puerto Ricans) from the present study is in support of the existing literatures.

Lastly, the authors would like to discuss one of our previous reports (Lee et al., 2017) examining the association between earlier single trajectories of only alcohol use beginning in adolescence and CUDs in adulthood using basically same data from the Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, although the time waves and sample size are different from the present study (N=674 in the previous report vs. N=816 in the present study). In this previous report, three-group model was selected, namely, the increasing, moderate, no or low alcohol use groups. However, the present study found no increasing alcohol use group among the five triple trajectory groups (the MHH, MHL, and MLL groups indicated moderate alcohol use, and the LNH and LNL groups indicated low alcohol use in Figure 1). There might be some interaction effects among the three variables (i.e., alcohol use, tobacco use, depressive symptoms), since the present study examined the three variables simultaneously in one analysis to obtain triple comorbid trajectories. Interactions by tobacco use and depressive symptoms on alcohol use may produce different results from the previous report in levels of alcohol use and impact on CUDs.

Limitations and Strengths

The sample consisted of an African American and Puerto Rican inner city population. Further studies should include other ethnic groups for generalization to the US population. The authors used three methods of administration (in person, by phone, or by mailed questionnaire) for the independent variables at T1–T3, which could have impacted the scores differentially. Although aspects of drug use are complicated, the use of drugs in the current study was assessed as a single item. Other psychological symptoms such as anxiety and impulsivity which could link to CUDs were not included. The number of items for depressive symptoms were inconsistent between the earlier two waves (T1, T2) and the later two waves (T3, T4); however, based on the high correlations, a proxy of Cronbach’s alpha, between the two items at T1 and T2 are 0.47 (p<.001) and 0.55 (p<.001), the measurement reliability is satisfactory. Our data are also based on self-reports which can lead to biased results since people may under-report their experiences with drug use. However, studies have shown that the use of this type of self-report data yields reliable results (Ledgerwood, Goldberger, Risk, Lewis, & Price, 2008).

Despite these limitations, the study supports and adds to the literature in a number of ways. First, we assess alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms at four points in time over a span of up to 15 years, whereas most research studies in this area focus on one point in time. The prospective nature of the data allowed us to go beyond a cross-sectional analysis and to consider the temporal sequencing of the variables. Second, a major contribution of the study is a unique set of findings associated with different triple trajectories of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms beginning in adolescence as related to adult CUD in a sample of African Americans and Puerto Ricans living in an urban area of New York City. Third, the association between earlier triple trajectories of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms and later CUD was maintained after controlling for gender, race/ethnicity, CUDs at age 29, and educational level at age 29.

CONCLUSIONS

The clinical implications of this study for prevention of CUDs may focus on the early use of both alcohol and tobacco as well as on the symptoms of depression. Prevention efforts must occur prior to the development of CUDs. This is critical for our sample, since these populations have the age crossover effect; that is, African Americans and Hispanic Americans appear to have a lower rate of substance use, but they catch up to European Americans with increasing age, and may surpass them later in life (Caraballo, Sharapova, & Asman, 2016; Watt, 2008; Zapolski, Baldwin, Banks, & Stump, 2017). Therefore, paying attention to substance use among African American and Puerto Rican adolescents may play an important role for prevention of CUDs in adulthood, even though little usage of substances occurs during adolescence.

Furthermore, depressive symptoms should not be ignored at early stages of development as treatment of depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood may help prevent the development of CUDs. From a public health perspective, our longitudinal study examining the associations between earlier triple trajectories of alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms and later CUDs, suggests that treatments designed to reduce or quit drinking as well as smoking, and to relieve depressive symptoms may reduce the prevalence of CUDs. In sum, we conclude that treatment programs for CUDs may be implemented in parallel with treatment programs focused on drinking, smoking, and depressive symptoms.

Future study should include the use of blunts (i.e., a combination of cannabis and tobacco) and examine the influence of blunts on CUDs, since preliminary research also indicates that cannabis and tobacco are often smoked on the same occasion, and these simultaneous users are at greater risk for CUDs (Agrawal et al., 2009). In addition, the effects of multiple drug trajectories including legal (e.g., alcohol and tobacco use) as well as illegal (e.g., cannabis use) drugs beginning in adolescence on mental disorders (e.g., major depressive disorders) may be investigated.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grant from the National Institutes of Health: 5K01 DA041609-02 awarded to Dr. Lee from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jung Yeon Lee, New York University School of Medicine.

Judith S. Brook, New York University School of Medicine

Wonkuk Kim, Chung-Ang University.

References

- Agrawal Arpana, Budney Alan J, Lynskey Michael T. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: a review. Addiction. 2012;107(7):1221–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal Arpana, Lynskey Michael T, Madden Pamela AF, Pergadia Michele L, Bucholz Kathleen K, Heath Andrew C. Simultaneous cannabis and tobacco use and cannabis-related outcomes in young women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101(1):8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer Reto, Vittinghoff Eric, Yaffe Kristine, Künzi Arnaud, Kertesz Stefan G, Levine Deborah A, … Sidney Stephen. Association between lifetime marijuana use and cognitive function in middle age: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(3):352–361. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman Jerald G, Wadsworth Katherine N, O'Malley Patrick M, Johnston Lloyd D, Schulenberg John E. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood: The impacts of new freedoms and new responsibilities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Association, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bagot Kara S, Milin Robert, Kaminer Yifrah. Adolescent initiation of cannabis use and early-onset psychosis. Substance Abuse. 2015;36(4):524–533. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.995332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Amanda L, Kavanagh David J, Kay-Lambkin Frances J, Hunt Sally A, Lewin Terry J, Carr Vaughan J, Connolly Jennifer. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive–behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems: short-term outcome. Addiction. 2010;105(1):87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieux M, Veran O, Detante O. Accidents vasculaires cérébraux ischémiques du sujet jeune et toxiques. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 2012;33(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden Joseph M, Fergusson David M, Horwood L John. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):440–446. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovasso Gregory B. Cannabis abuse as a risk factor for depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2033–2037. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd Carol J. Race/Ethnicity and Gender Differences in Drug Use and Abuse Among College Students. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2014;6(2):75–95. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S, Lee Jung Y, Finch Stephen J, Koppel Jonathan, Brook David W. Psychosocial factors related to cannabis use disorders. Substance Abuse. 2011;32(4):242–251. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.605696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S, Lee Jung Yeon, Brook David W. Trajectories of marijuana use beginning in adolescence predict tobacco dependence in adulthood. Substance Abuse. 2015;36(4):470–477. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.964901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S, Lee Jung Yeon, Brown Elaine N, Finch Stephen J, Brook David W. Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: personality and social role outcomes. Psychological Reports. 2011;108(2):339–357. doi: 10.2466/10.18.PR0.108.2.339-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S, Lee Jung Yeon, Finch Stephen J, Brown Elaine N. Course of comorbidity of tobacco and marijuana use: Psychosocial risk factors. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(5):474–482. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S, Stimmel Matthew A, Zhang Chenshu, Brook David W. The association between earlier marijuana use and subsequent academic achievement and health problems: A longitudinal study. The American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(2):155–160. doi: 10.1080/10550490701860930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldicott David GE, Holmes James, Roberts-Thomson Kurt C, Mahar Leo. Keep off the grass: marijuana use and acute cardiovascular events. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2005;12(5):236–244. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200510000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo Ralph S, Sharapova Saida R, Asman Katherine J. Does a race-gender-age crossover effect exist in current cigarette smoking between non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites? United States, 2001–2013. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;18(suppl_1):S41–S48. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton Michael O, Cohen Joanna E, O'Loughlin Jennifer, Rehm Jurgen. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton Wilson M, Grant Bridget F, Colliver James D, Glantz Meyer D, Stinson Frederick S. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991-1992 and 2001–2002. Jama. 2004;291(17):2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway Kevin P, Compton Wilson, Stinson Frederick S, Grant Bridget F. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):247–257. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland Jan, Clement Nicole, Swift Wendy. Cannabis use, harms and the management of cannabis use disorder. Neuropsychiatry. 2014;4(1):55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Curry John, Silva Susan, Rohde Paul, Ginsburg Golda, Kennard Betsy, Kratochvil Christopher, … Mayes Taryn. Onset of alcohol or substance use disorders following treatment for adolescent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(2):299. doi: 10.1037/a0026929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis Leonard R, Lipman Ronald S, Rickels Karl, Uhlenhuth Eberhard H, Covi Lino. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science. 1974;19(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DSM-IV. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington DC, MD: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin Renee D, Zvolensky Michael J, Keyes Katherine M, Hasin Deborah S. Mental disorders and cigarette use among adults in the United States. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21(5):416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant Bridget F, Goldstein Risë B, Saha Tulshi D, Chou S Patricia, Jung Jeesun, Zhang Haitao, … Huang Boji. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberstick Brett C, Young Susan E, Zeiger Joanna S, Lessem Jeffrey M, Hewitt John K, Hopfer Christian J. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol and cannabis use disorders in the United States: results from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;136:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin Deborah S, Kerridge Bradley T, Saha Tulshi D, Huang Boji, Pickering Roger, Smith Sharon M, … Grant Bridget F. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder 2012–2013: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner Jaimee L, DelBello Melissa P, Anthenelli Robert M, Fleck David E, Adler Caleb M, Strakowski Stephen M. Cigarette smoking and its relationship to mood disorder symptoms and co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders following first hospitalization for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2012;14(1):99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00985.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindocha Chandni, Shaban Natacha DC, Freeman Tom P, Das Ravi K, Gale Grace, Schafer Grainne, … Curran H Valerie. Associations between cigarette smoking and cannabis dependence: a longitudinal study of young cannabis users in the United Kingdom. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;148:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homel Jacqueline, Thompson Kara, Leadbeater Bonnie. Trajectories of marijuana use in youth ages 15–25: Implications for postsecondary education experiences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(4):674–683. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper Stephen R, Woolley Donald, De Bellis Michael D. Intellectual, neurocognitive, and academic achievement in abstinent adolescents with cannabis use disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231(8):1467–1477. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3463-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto Derek Kenji, Corbin William, Lejuez Carl, MacPherson Laura. College men and alcohol use: Positive alcohol expectancies as a mediator between distinct masculine norms and alcohol use. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2014;15(1):29. doi: 10.1037/a0031594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Eun-Jeong, Lee Jae-Hee. A longitudinal study on the causal association between smoking and depression. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2010;43(3):193–204. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2010.43.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann Laura, Kinchen Steven A, Williams Barbara I, Ross James G, Lowry Richard, Grunbaum Jo Anne, Kolbe Lloyd J. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 1999. Journal of School Health. 2000;70(7):271–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila Laurent, Roux Perrine, Rolland Benjamin, Benyamina Amine, Reynaud Michel, Aubin Henri-Jean, Lançon Christophe. Acute and long-term effects of cannabis use: a review. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2014;20(25):4112–4118. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C, Berglund Patricia, Demler Olga, Jin Robert, Merikangas Kathleen R, Walters Ellen E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Sharaf S, Secades-Villa Roberto, Okuda Mayumi, Wang Shuai, Pérez-Fuentes Gabriela, Kerridge Bradley T, Blanco Carlos. Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2013;130(1):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan Steven M, Cho Junhan, Oshri Assaf, Mackillop James. The influence of substance use on depressive symptoms among young adult Black men: the sensitizing effect of early adversity. The American Journal on Addictions. 2017;26(4):400–406. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner Matt G, Sher Kenneth J, Beitman Bernard D. The relation between alcohol problems and the anxiety disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147(6):685–695. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood David M, Goldberger Bruce A, Risk Nathan K, Lewis Collins E, Price Rumi Kato. Comparison between self-report and hair analysis of illicit drug use in a community sample of middle-aged men. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(9):1131–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jung Yeon, Brook Judith S, De La Rosa Mario, Kim Youngjin, Brook David W. The association between alcohol use trajectories from adolescence to adulthood and cannabis use disorder in adulthood: a 22-year longitudinal study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1288734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jung Yeon, Brook Judith S, Finch Stephen J, Brook David W. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood predicting unemployment in the mid 30s. The American Journal on Addictions. 2015;24(5):152–159. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Le Foll B, George TP, McKenzie K, Rehm J. The association between cannabis use and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(04):797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova Marya, Rabin Rachel A, George Tony P. Co-morbid tobacco use disorder and depression: A re--evaluation of smoking cessation therapy in depressed smokers. The American Journal on Addictions. 2015;24(8):687–694. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen Kelly P, Sutter Mark E, Albertson Timothy E. Marijuana: respiratory tract effects. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2014;46(1):65–81. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8374-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek Lauren R, Martins Silvia S, Crum Rosa M. The bidirectional relationships between alcohol, cannabis, co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders with major depressive disorder: results from a national sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;148(2):188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton George C, Coffey Carolyn, Carlin John B, Sawyer Susan M, Lynskey Michael. Reverse gateways? Frequent cannabis use as a predictor of tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2005;100(10):1518–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigucci S, Marques TR, Di Forti M, Taylor H, Dell'Acqua F, Mondelli V, … Girardi Paolo. Effect of high-potency cannabis on corpus callosum microstructure. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46(04):841–854. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room Robin. Research advances in alcohol and drug problems. Springer; 1990. Measuring alcohol consumption in the United States; pp. 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg John E, Maggs Jennifer L. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;(14):54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg John E, Maggs Jennifer L, O’Malley Patrick M. How and why the understanding of developmental continuity and discontinuity is important: the sample case of long-term consequences of adolsecent substance use. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the life course. New York: Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 413–436. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Joshua P, Book Sarah W. Comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorders among individuals seeking outpatient substance abuse treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(1):42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toray Tamina, Coughlin Chris, Vuchinich Samuel, Patricelli Peter. Gender differences associated with adolescent substance abuse: Comparisons and implications for treatment. Family Relations. 1991:338–344. doi: 10.2307/585021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Skike CE, Maggio SE, Reynolds AR, Casey EM, Bardo MT, Dwoskin LP, … Nixon K. Critical needs in drug discovery for cessation of alcohol and nicotine polysubstance abuse. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2016;65:269–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow Nora D, Baler Ruben D, Compton Wilson M, Weiss Susan RB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(23):2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt Toni Terling. The race/ethnic age crossover effect in drug use and heavy drinking. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2008;7(1):93–114. doi: 10.1080/15332640802083303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff Valérie, Armspach Jean-Paul, Lauer Valérie, Rouyer Olivier, Bataillard Marc, Marescaux Christian, Geny Bernard. Cannabis-related Stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(2):558–563. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.671347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Li-Tzy, Zhu He, Swartz Marvin S. Trends in cannabis use disorders among racial/ethnic population groups in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;165:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski Tamika CB, Baldwin Patrick, Banks Devin E, Stump Timothy E. Does a crossover age effect exist for African American and Hispanic binge drinkers? Findings from the 2010 to 2013 National Study on Drug Use and Health. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.1111/acer.13380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]