Abstract

Medical tourism has a potential of spreading multi-drug resistant bacteria (MDR). The Hadassah Medical Center serves as a referral center for global medical tourists and for Palestinian Authority residents. In order to assess whether patients of these groups are more likely to harbor MDR bacteria than local residents, we reviewed data from all patients admitted to our institution between 2009 and 2014. We compared MDR rates between countries of residency, controlling for gender, age, previous hospitalization and time from admission to MDR detection. Overall, among 111,577 patients with at least one microbiological specimen taken during hospitalization, there were 3,985 (3.5%) patients with at least one MDR-positive culture. Compared to Israeli patients, tourists and patients from the Palestinian Authority had increased rates of MDR positivity (OR, 95%CI): 2.3 (1.6 to 2.3) and 8.0 (6.3 to 10.1), respectively. Our data show that foreign patients seeking advanced medical care are more likely to carry MDR bacteria than the resident population. Strategies to minimize MDR spread, such as pre-admission screening or pre-emptive isolation should be considered in this population.

Introduction

Multi-drug resistant (MDR) organisms are a global threat1,2, leading to prolonged hospital stay, treatment failure, excess in-hospital death, and increased economic costs3–5. In order to prevent MDR bacteria cross-transmission and spread, hospitals employ isolation policies, including identification and preventive isolation measures of patients at high risk of carrying these bacteria6.

Medical tourism is not new; however, as a result of the shrinking global village, far more people seeking expert medical care travel between countries. Thus, there is an increased risk that medical tourism could lead to geographically dispersed outbreaks of communicable diseases, including the spread of MDR bacteria to non-endemic facilities7,8. Multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, including MBL-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, extended-spectrum beta lactamase and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, have been circulating the globe in recent years9–13.

Traditional risk factors for carriage of MDR bacteria include previous carriage, recent hospital stay, recent exposure to antibiotics and long-term care facility residence14. Currently, medical tourists are not considered a separate group that might require pre-emptive contact isolation15. Until now, most of the evidence regarding the potential threat of spreading resistant bacteria was based on single source epidemics associated with one traceable pathogen, or a resistance mechanism which was newly introduced to a country.

Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center serves as a referral center for global medical tourists and for residents of the Palestinian Authority. We sought to assess whether these patient populations are more likely to harbor resistant bacteria than local patients and thus may necessitate pre-emptive isolation until carriage status is determined.

Methods

Setting and patients

The Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center consists of two academic hospitals with a total of 1100 inpatient beds. Ein-Kerem campus is a 750 inpatient bed tertiary care center and Mount-Scopus campus is a 350 inpatient bed community hospital. The hospitals provide adult and pediatric medical, surgical and psychiatric services, including medical and surgical subspecialties, oncology, hematology, neurosurgery, transplantations and comprehensive outpatient and ambulatory services.

The source population from which we derived the study population included all patients who arrived at both centers of the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center between January 1st 2009 and December 31st 2014, including the emergency department, regular hospitalization and daycare. In order to account for a six-month hospitalization period prior to the inclusion date, the study period was limited to July 1st 2009 through December 31st 2014. The analysis was performed only on patients who were admitted as inpatients at least once during the study period and from whom at least one microbiological specimen was obtained during this time (Fig. 1). All data in the study was collected from the computerized institutional repository. We extracted age, gender and nationality as well as hospital-referrals and intensive care unit (ICU) stays during the study period, and the prior six months.

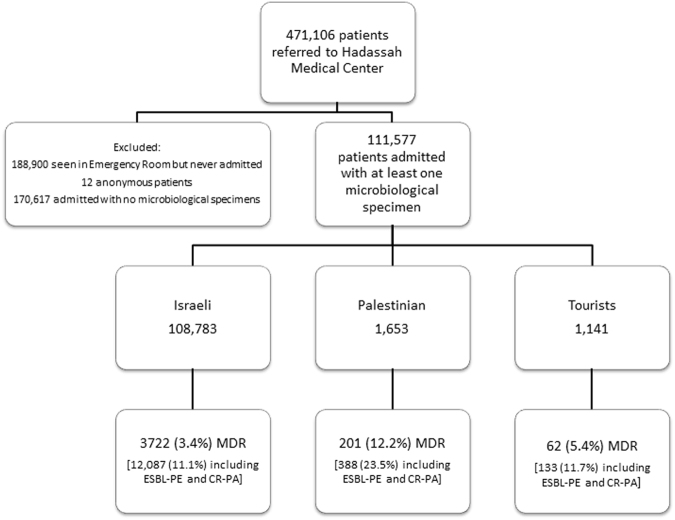

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient selection, exclusion and multi drug resistant (MDR) rates. The study period extended from July 1st 2009 to December 31st 2014. Only patients admitted at least once and from whom at least one microbiological specimen was obtained were included in the study. Patients were classified into three groups and in each, the rate of MDR bacteria was calculated twice, once excluding and once including carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CR-PA) and extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) (see text).

Patient nationality was defined as Israeli citizens, residents of the Palestinian Authority and foreign tourists. Patients from the Palestinian Authority usually receive care from Palestinian medical services and arrive at Israeli medical centers for more advanced investigations and treatments. In all cases of foreign tourists found to be MDR positive, we examined the patient files to assess whether they were medical tourists who came to Israel for treatment. Patients were stratified into five age-groups: 0–18, 19–40, 41–65, 66–80 and above 80 years of age.

The Hadassah Hebrew University Medical Center ethics committee approved the study and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Specimens and multi drug resistance (MDR)

Microbiological data from all clinical and screening specimens was extracted from the microbiology laboratory computerized database (WHONET)16. Clinical specimens are obtained based on patient’s clinical status and according to the discretion of the attending physician. Screening is carried out upon admission for every patient with risk factors for MDR carriage (hospital admission in previous six months or residency in long-term-care facility). These risk factors are assessed by the nursing staff upon admission and define the necessity for screening. MDR Screening is also performed for all intensive care unit patients upon admission and once weekly. The data included all specimens sent for culture and Clostridium difficile toxin (CDT) tests. In our hospital, bacteria considered multi drug resistant (MDR) that require contact isolation precautions include: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE); carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CR-ACIN); methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) and Clostridium difficile. For simplicity, in this report these five bacteria groups are all termed MDR. Additionally, we present secondary data regarding carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CR-PA) and extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE), which in our institution do not necessitate contact isolation and are not defined as MDR bacteria in this study’s primary analysis.

Microbiological methods

Resistant bacteria isolates reported in this study were of two origins: a. Strains from clinical samples with resistance to the antibiotic of interest (i.e. carbapenems for CRE and A. baumannii, cefoxitin and oxacillin for MRSA, vancomycin for VRE, and 3rd generation cephalosporins for ESBL-PE). b. Strains with the above mentioned resistance identified as part of the institutional rectal/nasal screening protocols

The clinical samples were processed according to the routine laboratory diagnostic flow, which included identification by classical biochemical methods relevant at that time17 or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF). Antimicrobial sensitivity testing was performed using the disk-diffusion method according to CLSI standards in the concordant years18,19. Suspected CRE were further verified for carbapenemase production using the modified Hodge test11,20. The screening samples were processed as follows: rectal/nasal swabs were plated onto selective chromogenic media (ChromAgar KPC/ChromAgar ESBL/ChromAgar MRSA, HyLabs, Rehovot, Israel) and incubated at 35 °C for 18–24 hours. Suspected colonies were identified using classical biochemical methods relevant at that time or MALDI-TOF17. Following identification of CRE, A. baumannii and ESBL-PE, a designated antimicrobial sensitivity testing panel was used to verify resistance to carbapenems and 3rd generation cephalosporins, respectively. Additionally, for CRE, a modified Hodge test was performed to verify the production of carbapenemases20. For VRE, rectal swabs were plated on VRE media (Novamed, Jerusalem, Israel) and incubated at 35 °C for 18–24 hours. Esculin hydrolyzing colonies were further identified by MALDI-TOF to exclude enterococci other than E. faecium and E. fecalis. Prior to 2012, CDT was diagnosed using an enzyme immuno-assay (Meridien Life Sciences, TN, USA). From 2012 onwards, CDT was diagnosed using a home-brewed Sybr green based real-time PCR performed on fecal DNA extracted by easyMag (bioMerieux, NC, USA).

Data Analysis

The demographic data repository and the clinical microbiology lab repository were cross-referenced. Initially we recorded for every patient whether any culture specimen or CDT test was performed. Among patients with at least one specimen tested, we identified MDR positive specimens and recorded the date of the first positive specimen. Patients with at least one positive MDR isolate were defined MDR-positive patients. The date of the first MDR bacterium detected was defined as the patient’s index date.

In order to assess community acquisition vs. hospital acquisition, the time from hospital admission to the index date was recorded for MDR-positive patients. The dates were stratified into three time-groups: up-to 96 hours from admission, 96 hours to one week or greater than one week. We expanded the commonly used time span of 72 hours to 96 hours, taking into account a possible delay between the actual time of culturing and registration of the specimen in the lab.

We calculated the rate of MDR-positive patients (out of all included patients) per population, age and time groups. In addition, we calculated the rate of the first positive specimen for each specific MDR pathogen per patient and present these rates per nationality. Since more than one MDR bacteria can be present in a single patient, the sum of the rates per specific MDR pathogen exceeds the crude rate of MDR-positive patients.

We attempted to account for exposure to a healthcare facility prior to MDR bacteria identification. To this end, we counted the total number of admissions to our hospitals in the six months preceding the first MDR isolation. Hospitalization data was available for prior admissions only to our medical center. In order to assess the role of prior healthcare exposure on the risk of MDR positivity, a comparison with MDR-negative patients was required. As there is no index date for MDR-negative patients, in order to minimize possible biases, we defined the earliest admission date with the maximal number of prior six-month hospitalizations as the index date of a given patient.

In addition, we examined the rate of CDT positivity among all patients for whom the test was performed.

Logistic regression was performed to control for age and gender and to examine if nationality is associated with MDR bacteria carriage risk. When analyzing this model for all MDR bacteria, we also controlled for previous hospital exposure. However, when analyzing this model for a specific MDR pathogen, previous hospital exposure was excluded because some patients acquired a specific pathogen long after acquiring a previous pathogen and therefore previous admissions were not relevant to the latter acquisition. In each model we generated a random sample of controls three times larger than the case group, in order to prevent data skewing and mathematically biased results.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

During the study period, there were 942,702 referrals of 471,106 patients to the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center; among them 111,577 patients met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most patients were not admitted to our institution in the prior six months; however, previous admissions were more common among Israeli patients. Palestinian Authority patients had a higher proportion of younger patients while Israelis included more patients above 80 years of age. ICU stay in the prior six months was more often found among Palestinian patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 111,577).

| Variable | N (%) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Israeli | Palestinian Authority | Foreign tourists | |

| Number of patients | 108,783 | 1653 | 1141 | |

| Female gender | 61,754 (57%) | 641 (39%) | 572 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| Up to 18 | 31,488 (29) | 653 (40) | 162 (14) | <0.001 |

| 18 to 40 | 31,115 (29) | 465 (28) | 291 (26) | |

| 40 to 65 | 21,974 (20) | 401 (24) | 389 (34) | |

| 65 to 80 | 14,840 (14) | 108 (7) | 227 (20) | |

| above 80 | 9,366 (9) | 26 (2) | 72 (6) | |

| Previous 6 months admissions | ||||

| None | 61,872 (57) | 1,152 (70) | 867 (76) | <0.001 |

| One | 31,839 (29) | 267 (16.2) | 176 (15) | |

| More than one | 15,072 (14) | 234 (14) | 98 (9) | |

| ICU stay, previous 6 months | 4,661 (4.3) | 107 (6.5) | 37 (3.2) | <0.001 |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Overall, there were 3,985 (3·5%) patients with MDR bacteria. MDR positivity rates were highest among Palestinians (12·2%) followed by tourists (5·4%) and Israeli residents (3·4%) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Including ESBL-PE and CR-PA there were 12,608 (11·3%) MDR positive patients: 10,271 ESBL-PE and 826 CR-PA.

The distribution of MDR positivity (MDR positive patients out of all included patients) per stratum of time from hospital admission to first MDR incidence is presented in Table 2. In 1,722/3,985 (43·2%) MDR events, identification occurred within 96 hours from hospital admission. In the additional analysis including ESBL-PE and CR-PA, 7,646/12,608 (60·6%) of the events were identified within 96 hours from hospital admission.

Table 2.

Multi drug resistant carriage rates.

| Variable | N (%) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Israeli | Palestinian Authority | Foreign tourists | Total | |

| Number of patients | 108,783 | 1,653 | 1,141 | 111,577 | |

| MDR positivity (overall) | 3,722 (3.4) | 201 (12.2) | 62 (5.4) | 3,985 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| MDR positivity according to time after hospital admission | |||||

| Up to 96 hours | 1,590 (1.5) | 96 (5.8) | 36 (3.2) | 1,722 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| 96 hours–1 week | 352 (0.3) | 16 (1.0) | 4 (0.4) | 372 (0.3) | |

| More than one week | 1,780 (1.6) | 89 (5.4) | 22 (1.9) | 1,891 (1.7) | |

| MDR-specific positivity rates | |||||

| CRE | 769 (0.7) | 31 (1.9) | 19 (1.7) | 819 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| VRE | 616 (0.6) | 25 (1.5) | 16 (1.4) | 657 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| MRSA | 1,205 (1.1) | 58 (3.5) | 13 (1.1) | 1,276 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| CR_ACIN | 770 (0.7) | 73 (4.4) | 17 (1.5) | 860 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| C. difficile* | 1,393 (1.3) | 56 (3.4) | 16 (1.4) | 1,465 (1.3) | <0.001 |

*C. difficile positivity rates among patients whose stool samples were tested: Israeli 15.7%, Palestinian 17.6%, foreign tourists 9.8%.

MDR, multi-drug resistant; CRE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CR-ACIN, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

C. difficile toxin tests were performed for 9339 (8·4%) of all included patients. C. difficile was the most prevalent MDR bacterium (1·3%) followed by MRSA (1·1%) (Table 2). Per specific MDR bacteria, Palestinian patients had the highest carriage rates for all bacteria, and CR-ACIN was the most prevalent (4·4%). For most MDR positive patients, only a single MDR type was identified (3160, 79·3%). Bacteremia was the first presentation of MDR infection in 260/3,985 (6·5%) cases.

Distribution of MDR positive foreign tourists according to geographic origin was as follows: East Europe, 46/586 (7·8%); North America and Western Europe, 12/369 (3·2%); all other, 4/179 (2·2%).

Among MDR positive foreign patients 49/62 (79%) were medical tourists. Among medical tourists, MDR were identified on their first visit to our institution in 28/49 (57%) cases. Among non-medical tourists MDR was identified during their first visit to our institution in only 1/13 (8%) cases.

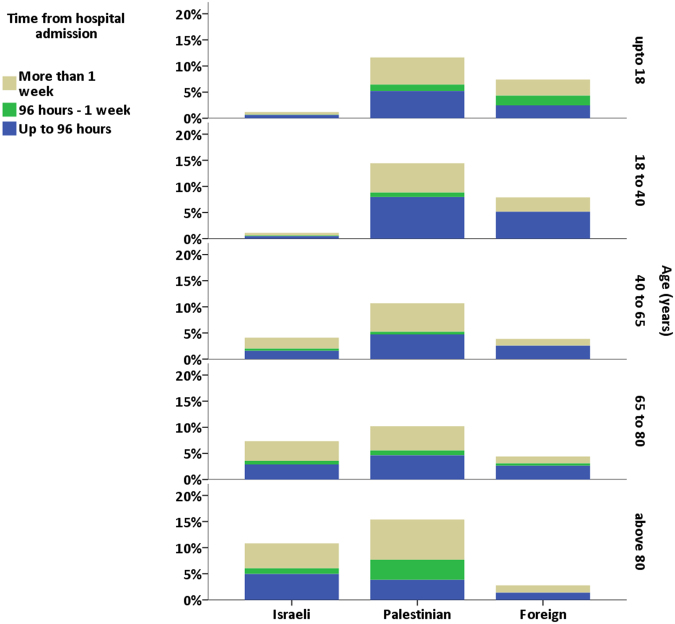

Positivity rates, stratified by nationality, age group and time from admission, are presented in Fig. 2 (data shown in Supplementary Table S1). MDR positivity was highest among Palestinians in all age groups. MDR positivity among Israelis increased with age. In contrast, among foreign patients, MDR positivity rates were highest in the younger patients and rates decreased with age. In Supplementary Figure S1 we present similar results with inclusion of ESBL-PE and CR-PA.

Figure 2.

Multi drug resistant (MDR) prevalence per age group and source population. Each panel depicts MDR prevalence per age group. Columns depict the cumulative MDR rate in each age group, per patient nationality. The color specifications depict the time from hospital admission to first identification of MDR bacteria. Palestinian patients were found to have the highest rates of MDR bacteria in all age groups. Among patients up to 40 years old, foreign tourists had higher MDR rates than Israeli patients. In the older age groups, MDR rates were lower among foreign tourists. In most age groups about half of MDR bacteria were identified in the first 96 hours after admission.

The results of the regression model are presented in Table 3. Controlling for gender, age and previous hospital admission (only in the model for any MDR bacteria), Palestinian and foreign tourists were associated with increased risk of MDR positivity (OR, 95%CI: 8·0, 6·3 to 10·1; 2·3, 1·6 to 3·3, respectively). Results were similar when limiting the analysis to patients among whom MDR were identified during the first 96 hours after admission (data not shown) and for a specific bacteria. More than one previous hospitalization in the prior six months was also associated with increased rates of MDR positivity (OR 1·6, 95%CI 1·4 to 1·8).

Table 3.

Regression models assessing the risk of multi-drug resistant bacteria positivity.

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Any MDR bacteria* | CRE | VRE | MRSA | CR-ACIN | C. difficile |

| Female | 0.68 (0.63 to 0.74) | 0.65 (0.54 to 0.78) | 0.79 (0.65 to 0.96) | 0.6 (0.52 to 0.68) | 0.48 (0.41 to 0.56) | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.92) |

| Residence (reference: Israeli patients) | ||||||

| Palestinian | 8.0 (6.3 to 10.1) | 6.8 (3.8 to 12.1) | 7.3 (3.8 to 13.7) | 5.1 (3.4 to 7.6) | 13.5 (8.4 to 21.7) | 5.7 (3.8 to 8.5) |

| Foreign tourists | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.3) | 4.9 (2.4 to 10.1) | 2.5 (1.2 to 5.1) | 0.85 (0.45 to 1.65) | 2.7 (1.4 to 5.4) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.9) |

| Age (reference: age up to 18) | ||||||

| 18 to 40 | 1.05 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.9 (1.2 to 2.8) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.6) | 0.8 (0.63 to 1.0) | 3.5 (2.5 to 5.1) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| 40 to 65 | 3.2 (2.8 to 3.6) | 7.6 (5.3 to 11.1) | 10.9 (7.2 to 16.4) | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.6) | 9.5 (6.7 to 13.3) | 3 (2.4 to 3.8) |

| 65 to 80 | 5.9 (5.2 to 6.7) | 19 (13.1 to 27.4) | 16.6 (11 to 25.2) | 4.0 (3.2 to 4.9) | 11.6 (8.3 to 16.4) | 6.4 (5.2 to 8) |

| above 80 | 9.1 (7.9 to 10.4) | 26 (17.8 to 38.1) | 18.2 (11.8 to 28.2) | 4.6 (3.7 to 5.8) | 15.8 (11 to 22.8) | 11.5 (9.3 to 14.5) |

MDR, multi-drug resistant; CRE, carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae; VRE, vancomycin resistant Enterococci; CR-ACIN, carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

*The model was also controlled for hospitalization in the prior six months.

Discussion

In this study, which summarizes data from six years, including almost a million hospital referrals from nearly half a million patients, we found that patients of foreign origin, including residents of the Palestinian Authority and foreign tourists, have higher rates of MDR bacteria than Israeli patients. The chances of carrying MDR were higher among Palestinian Authority patients than patients arriving from other countries. These data are in accord with earlier reports of high MDR prevalence in the Palestinian Authority21,22.

Though non-Israeli patients had less prior exposure to our institution, we believe this does not reflect their true exposure to medical institutions prior to arrival to our center. Among foreign tourists, most MDR positivity was found among medical tourists, with the younger age groups presenting higher rates of MDR-bacteria. Most medical tourists with MDR bacteria were from East Europe, where there have been reports of high rates of MDR bacteria23. We hypothesize that most Palestinians seeking medical care in our hospitals are a selected group who were exposed to other medical institutions prior to their admission. Therefore, we can probably relate to the majority of patients in this group as medical tourists, although data regarding previous hospitalizations of Palestinian patients in the Palestinian Authority or elsewhere was not available.

Medical tourists are patients seeking medical treatment out of their homeland who have been often exposed to medical care in institutions in their country of origin before their referral to other countries. As hospitals are reservoirs for MDR bacteria, medical tourists are a particular concern regarding the spread of MDR bacteria between countries23. In addition it has been shown that patients with a recent history of travel to MDR-endemic areas (but not admitted to healthcare facilities abroad) were found to have increased rates of carriage of MDR organisms. The highest prevalence was observed in travelers returning from southern Asia2,7,9.

We suggest that the higher MDR bacteria rates among foreign patients found in our study reflect increased risk due to frequent hospitalizations as well as high MDR bacteria prevalence in their places of origin. Introduction of resistant bacteria from Palestinians and tourists has been previously reported24,25.

In a cross-sectional survey of nasal S. aureus carriage in healthy children and their parents throughout the Gaza strip (which is part of the Palestinian Authority), MRSA was detected in 12% of the study population and 45% of S. aureus isolates were MRSA22. Antibiotic self-medication practices and over the counter purchase of antibiotics, reported as common in the Palestinian Authority, probably contribute to the high MDR prevalence26,27. Additionally, accessibility to broad spectrum antibiotics via direct donations may also attribute, and thus such observation can be implicated to patients arriving from other low resource countries.

Healthcare institutions should have sound infection prevention strategies to mitigate the risk of dissemination of MDR organisms from patients previously hospitalized in other countries. In order to prevent the spread of MDR bacteria, pre-emptive prevention policies should be established. One such option would require medical tourists to undergo carriage screening before arriving at the expert centers. This course would require standard and validated specimen collection, culturing and assessment methods. In many instances, medical tourists come from less privileged areas where there is less access (geographical or financial) to well standardized medical microbiological services. Therefore, a more practical approach would be to screen foreign patients upon admission, especially those from known areas endemic for MDR bacteria, and to apply contact precautions pending result of screening cultures28. This strategy is known to be applied in some countries with low MDR prevalence3,29–31.

This study has several limitations. Working with such a large data repository does not allow in depth case analysis. Therefore, information on cause of admission, comorbidities and prior antibiotic exposure was not included in this report. The denominator of the calculated carriage rates was the number of patients who were sampled and not all admitted patients; cultures were collected from 40% (111,577/282,194) of admitted patients (Fig. 1). Additionally, patients for whom clinical cultures were taken but were MDR negative cannot be ruled out as MDR bacteria carriers. However this (non-differential) bias exists in all study groups and therefore would only serve to underestimate the real differences between patient groups32. Indeed, we found high rates of MDR bacteria among non-Israeli patients also in the third time interval (more than one week after admission) probably representing an undetected MDR carriage state.

Among Palestinians, we do not have enough information to establish which patients were medical tourists and whether they were previously exposed to healthcare facilities in the Palestinian Authority. In either event, this patient group had markedly higher MDR bacteria rates. Identifying specific risk factors associated with MDR bacteria carriage (e.g. previous hospitalization, long term care facility residence, and previous antibiotic treatment) could improve targeted screening and isolation resources. Regional initiatives currently underway between Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and several medical institutions in the Palestinian Authority are intended to improve our information in these areas and promote better infection control practices in all cooperating parties.

Data on prior antimicrobial exposure and prior hospital admission could have provided better identification of patient groups for focused screening of MDR carriage. However, definition and criteria of these characteristics are fluid, and in many cases, the available medical documentation, if any, is poorly understood. We think that our proposal to identify non-local patients as a group with higher MDR propensity is more practical for implementation in other countries.

In conclusion, we found that in addition to the general risk factors of MDR bacteria carriage, foreign patients seeking advanced medical care are more likely to carry MDR bacteria than residents. Institutions should identify their specific specialties that attract medical tourists, and perform a stratified risk analysis for screening, pre-emptive isolation and decolonization of specific patients, based on gender, age, previous hospitalization and country of origin. Maps of country-specific MDR prevalence should be publically available and routinely updated in order to provide better care for medical tourists and reduce the risk of bacterial transmission in the host countries.

Electronic supplementary material

Author Contributions

Shmuel Benenson: This author conceived and designed the study, participated in data collection, performed the data analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. Ran Nir-Paz: This author participated in study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Mordechai Golomb: This author participated in the data collection, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Carmela Schwartz: This author participated in the data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Sharon Amit: This author participated in the data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Allon E. Moses: This author participated in study design, oversight and manuscript preparation. Matan J. Cohen: This author conceived and designed the study, participated in data collection, performed the data analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors have contributed to, seen, and approved the final, submitted version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-27908-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marston HD, Dixon DM, Knisely JM, Palmore TN, Fauci AS. Antimicrobial Resistance. JAMA. 2016;316:1193–1204. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’neill, J. Review on Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. (2014).

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. (2013).

- 4.President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. Report to the President on combating antibiotic resistance. (2014).

- 5.The Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. The State of the World’s Antibiotics, 2015. Washington, D.C. (2015).

- 6.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:S65–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassing, R. J. et al. International travel and acquisition of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a systematic review. Euro Surveill20 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.van der Bij AK, Pitout JD. The role of international travel in the worldwide spread of multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2090–2100. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arcilla MS, et al. Import and spread of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by international travellers (COMBAT study): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:78–85. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30319-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldfarb D, et al. Detection of plasmid-mediated KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Ottawa, Canada: evidence of intrahospital transmission. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1920–1922. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poirel L, Lagrutta E, Taylor P, Pham J, Nordmann P. Emergence of metallo-beta-lactamase NDM-1-producing multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in Australia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4914–4916. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00878-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yong D, et al. Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5046–5054. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tien HC, et al. Multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter infections in critically injured Canadian forces soldiers. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Bano J, et al. Community-onset bacteremia due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: risk factors and prognosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:40–48. doi: 10.1086/649537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crooks, V. A. et al. Ethical and legal implications of the risks of medical tourism for patients: a qualitative study of Canadian health and safety representatives’ perspectives. BMJ Open3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.O’Brien TF, Stelling JM. WHONET: an information system for monitoring antimicrobial resistance. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:66. doi: 10.3201/eid0102.950209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray, P. R. & Baron, E. J. Manual of clinical microbiology, (ASM Press, Washington, D.C., 2007).

- 18.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests; Approved Standard-Tenth Edition. CLSI document M02-A10. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. (2009).

- 19.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twentieth Infomational Supplement (June 2010 Update). CLSI document M100-S20U. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. (2010).

- 20.Lee K, et al. Modified Hodge and EDTA-disk synergy tests to screen metallo-beta-lactamase-producing strains of Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:88–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abu-Taha AS, Sweileh WM. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial strains isolated from patients with community-acquired urinary tract infections: an exploratory study in Palestine. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2011;6:304–307. doi: 10.2174/157488411798375930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biber A, et al. A typical hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone is widespread in the community in the Gaza strip. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summary of the latest data on antibiotic resistance in the European Union EARS-Net surveillance data November 2015 (2015).

- 24.Adler A, et al. Persistence of Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 as the predominant clone of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in post-acute-care hospitals in Israel, 2008–13. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:89–92. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler A, et al. Introduction of OXA-48-producing Enterobacteriaceae to Israeli hospitals by medical tourism. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2763–2766. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammad J, Qusa H, Elessi K, Aljeesh Y. The Dispensing Practice Of The Over The Counter Drugs In The Gaza Strip. IUG Journal of Natural and Engineering Studies. 2012;20:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawalha AF. A descriptive study of self-medication practices among Palestinian medical and nonmedical university students. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2008;4:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen E, Mohsin J. Should travelers be screened for multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria after visiting high risk areas such as India? Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaspar T, Schweiger A, Droz S, Marschall J. Colonization with resistant microorganisms in patients transferred from abroad: who needs to be screened? Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:31. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0071-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepelletier D, Andremont A, Grandbastien B. Risk of highly resistant bacteria importation from repatriates and travelers hospitalized in foreign countries: about the French recommendations to limit their spread. J Travel Med. 2011;18:344–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers BA, Aminzadeh Z, Hayashi Y, Paterson DL. Country-to-country transfer of patients and the risk of multi-resistant bacterial infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:49–56. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359:248–252. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.