ABSTRACT

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) elicit opsonophagocytic (opsonic) antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides (PPS) and reduce nasopharyngeal (NP) colonization by vaccine-included Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes. However, nonopsonic antibodies may also be important for protection against pneumococcal disease. For example, 1E2, a mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody (MAb) to the serotype 3 (ST3) PPS (PPS3), reduced ST3 NP colonization in mice and altered ST3 gene expression in vitro. Here, we determined whether 1E2 affects ST3 gene expression in vivo during colonization of mice by performing RNA sequencing on NP lavage fluid from ST3-infected mice treated with 1E2, a control MAb, or phosphate-buffered saline. Compared to the results for the controls, 1E2 significantly altered the expression of over 50 genes. It increased the expression of the piuBCDA operon, which encodes an iron uptake system, and decreased the expression of dpr, which encodes a protein critical for resistance to oxidative stress. 1E2-mediated effects on ST3 in vivo required divalent binding, as Fab fragments did not reduce NP colonization or alter ST3 gene expression. In vitro, 1E2 induced dose-dependent ST3 growth arrest and altered piuB and dpr expression, whereas an opsonic PPS3 MAb, 5F6, did not. 1E2-treated bacteria were more sensitive to hydrogen peroxide and the iron-requiring antibiotic streptonigrin, suggesting that 1E2 may increase iron import and enhance sensitivity to oxidative stress. Finally, 1E2 also induced rapid capsule shedding in vitro, suggesting that this may initiate 1E2-induced changes in sensitivity to oxidative stress and gene expression. Our data reveal a novel mechanism of direct, antibody-mediated antibacterial activity that could inform new directions in antipneumococcal therapy and vaccine development.

KEYWORDS: serotype 3, Streptococcus pneumoniae, antibody function, capsule, iron acquisition, monoclonal antibodies, nasopharyngeal colonization, pneumococcus

INTRODUCTION

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) elicit anticapsular antibodies that promote opsonophagocytic (opsonic) killing of homologous serotypes (STs) in vitro. Such antibodies are an important correlate of protection against invasive pneumococcal disease, although recent studies have shown poor correlations between serum opsonic antibody titers and protection for some serotypes, including serotype 3 (ST3) (1–4). The opsonic activity of PCV-induced antibodies requires the interaction of antibody Fc regions with host cell Fc receptors (FcR). Indeed, many classical mechanisms of antibody activity, such as enhancement of opsonophagocytosis, complement deposition, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, are dependent on Fc-FcR- or complement receptor-mediated responses (5). However, there are also direct, host-independent mechanisms of antibody activity against bacterial pathogens, including lytic pore formation, alteration of metabolism, and disruption of virulence processes (6–11). A recent report also described the direct effects of glycolipid conjugate vaccine-elicited immune serum on Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression (12).

The current 13-valent PCV (PCV13) is less effective against ST3 than against other STs (1, 13–16), highlighting the need for a better understanding of vaccine-mediated protection against ST3. Our group is interested in how pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide (PPS) antibodies protect against pneumococcal disease, particularly ST3 disease (17–21). We previously identified an ST3 PPS (PPS3)-binding mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody (MAb), 1E2. 1E2 does not promote opsonic killing of ST3 in vitro, yet it protects mice against lethal ST3 pneumonia and sepsis and reduces ST3 nasopharyngeal (NP) colonization (19, 22). The ability of 1E2 to reduce ST3 NP colonization and prevent ST3 dissemination to the blood and lungs of mice did not require its Fc region (18, 22), suggesting that its mechanism of action involves a direct effect on ST3 in the NP. This hypothesis is consistent with the demonstrated ability of 1E2 to alter ST3 gene expression in vitro (23). In this study, we determined the effect of 1E2 on ST3 gene expression in vivo during NP colonization in mice. We found that 1E2 altered the expression of more than 50 genes compared to the expression achieved with a control MAb. All genes in the piuBCDA operon, encoding the iron import complex, were upregulated, and the gene encoding an oxidoprotective iron-binding protein, dpr, was downregulated. We also found that 1E2 triggers capsule shedding and enhances ST3 sensitivity to iron-mediated oxidative stress in vitro. These results provide direct evidence for antibody-mediated effects on pneumococcal gene expression in vivo and insight into how these effects may translate into decreased bacterial viability during NP colonization.

RESULTS

1E2 alters ST3 gene expression during NP colonization.

We first tested the effects of 1E2 (a nonopsonic PPS3 IgG1 MAb) on NP colonization relative to those of 5F6 (an opsonic PPS3 IgG1 MAb), 31B12 (a PPS8-specific IgG1 MAb, here referred to as the control MAb), or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). 1E2 reduced the level of colonization and prevented dissemination relative to the control MAb, as previously described (22), whereas 5F6 had no effect on colonization or dissemination (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We also tested the ability of 1E2 fragments to reduce the number of NP CFU and found that F(ab′)2 fragments retained the ability to reduce colonization, as previously described (22), whereas Fab fragments did not (Fig. S2A).

We then analyzed by transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) bacterial gene expression in NP lavage samples obtained 24 h after ST3 colonization of mice treated with 1E2, the control MAb, or PBS. In a single experiment, we also treated mice with 7A9, an opsonic PPS3 IgG1 MAb that does not reduce NP colonization (22). Unfortunately, further studies with this MAb were not possible as the cell line was lost. After filtering out genes with low expression (see Materials and Methods), we examined the expression of the remaining 1,884 ST3 genes (Data Set S1). Since there were no significant differences in ST3 gene expression between mice that received the control MAb and mice that received PBS (Data Set S2, control versus PBS), results obtained under control MAb and PBS treatment conditions were combined to increase the statistical power (here referred to as “the control condition”). A stringent cutoff of a ∣fold change (FC)∣ in expression of >3 and an adjusted P value (Padj) of <0.05 was used to identify differentially expressed (DE) genes (see Materials and Methods).

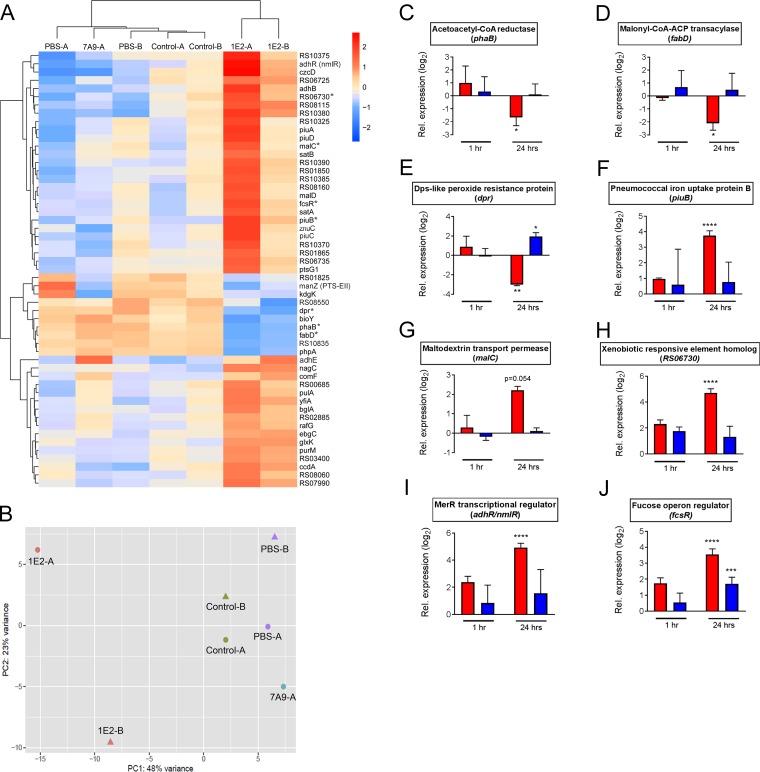

Compared to the levels of gene expression under the control condition, treatment with 1E2 significantly increased the expression of 43 genes and decreased the expression of 10 genes. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis of these genes showed that the effect of 1E2 on ST3 gene expression was distinct from the effects of PBS, the control MAb, and 7A9 (Fig. 1A and B). Differentially expressed genes in 1E2-treated mice showed a statistically significant enrichment of those encoding proteins predicted to localize to the bacterial surface (P = 0.0017; Fig. S3). Functional classification of genes with increased expression in 1E2-treated mice revealed numerous genes involved in carbohydrate transport/metabolism and inorganic ion transport (Table 1), a trend that was also observed when using a less stringent cutoff for differential expression (FC > 2, Padj < 0.05; Table S1). Strikingly, every gene in the piuBCDA iron import operon was upregulated >4-fold in 1E2-treated mice (Table 1). Notable downregulated genes included two genes required for fatty acid biosynthesis, fabD and phaB, and dpr, which is required for pneumococcal resistance to iron-mediated oxidative stress (24) (Table 2). Complete lists of genes upregulated (FC > 2) or downregulated (FC < −2) in 1E2-treated mice with the predicted protein localization and functional classification based on the clusters of orthologous groups (COG) class are shown in Tables S1 and S2.

FIG 1.

1E2 alters ST3 gene expression during nasopharyngeal colonization of mice. (A) Mice were treated with 1E2, 7A9, a control MAb, or PBS for 2 h before intranasal infection with ST3 in 10 μl PBS. ST3 gene expression at 24 h postinfection was determined by RNA-seq in two independent experiments (experiments A and B) using RNA purified from pooled lavage fluid from 6 to 10 mice per treatment. A heatmap and a hierarchical clustering of log2-transformed fold changes in expression of differentially expressed genes in 1E2-treated mice compared to their expression under the combined control conditions (treatment with control MAb and PBS) are shown. The color scale is representative of relative expression, as follows: red, upregulated; blue, downregulated. Asterisks indicate the genes tested by RT-qPCR, the results of which are presented in panels C to J. (B) Principal component (PC) analysis of gene expression data from all samples in panel A. (C to J) Mice were treated with 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb for 2 h before ST3 infection, as described in the legend to panel A. Expression of the indicated genes in 1E2- or 5F6-treated mice (red and blue bars, respectively) relative to that in the control MAb-treated mice at 1 or 24 h postinfection was determined by RT-qPCR. For relative expression values of >2 or <−2, P values for the difference in expression relative to that in control MAb-treated mice were determined by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test on nontransformed FC values at the same time points. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from two independent experiments using two replicates per group per experiment. CoA, coenzyme A; ACP, acyl carrier protein.

TABLE 1.

Functional grouping of ST3 genes upregulated in the NP of 1E2-treated mice

| Gene function and gene | Gene name | Description | Localizationa | FC in expressionb | Padj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate transport | |||||

| RS07990 | Hypothetical protein | Unknown | 3.8 | 8.3E−05 | |

| RS08000 | nanU | Sialic acid ABC transporter permease | Membrane | 4.3 | 2.2E−03 |

| RS08005 | nanV | Sialic acid ABC transporter permease | Membrane | 3.2 | 1.5E−02 |

| RS08015 | nanP | Sialic acid PTSd transporter subunit IIBC | Membrane | 3.2 | 1.0E−02 |

| RS09035 | rafG | Sugar ABC transporter permease | Membrane | 3.4 | 8.6E−03 |

| RS10330c | malC | Maltodextrin ABC transporter permease | Membrane | 3.4 | 1.9E−02 |

| RS10335 | malD | Maltodextrin ABC transporter permease | Membrane | 3.5 | 1.2E−02 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | |||||

| RS01575 | bglA3 | 6-Phospho-beta-glucosidase | Cytoplasm | 3.3 | 1.5E−03 |

| RS01590 | pulA | Alkaline amylopullulanase | Cell wall | 3.3 | 1.0E−03 |

| RS05550 | glxK | Glycerate kinase | Unknown | 3.5 | 5.5E−05 |

| RS07995 | ebgC | Beta-galactosidase subunit beta | Cytoplasm | 3.1 | 3.1E−03 |

| RS10480 | nagC | ROK sugar kinase | Cytoplasm | 5.2 | 3.7E−04 |

| RS10605 | fcsR | DeoR family transcriptional regulator | Cytoplasm | 5.4 | 5.6E−03 |

| Oxidative/aldehyde stress response | |||||

| RS03230 | ccdA | Cytochrome c biogenesis protein | Membrane | 3.8 | 9.0E−03 |

| RS08830 | adhB | Zinc-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase | Cytoplasm | 5.0 | 3.7E−04 |

| RS08835 | adhR (nmlR) | MerR transcriptional regulator | Cytoplasm | 6.7 | 3.7E−04 |

| RS10550 | Iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase | Cytoplasm | 6.3 | 1.0E−03 | |

| Cation transport | |||||

| RS08160 | znuC | Multidrug ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | Membrane | 3.6 | 1.1E−02 |

| RS08840 | czcD | Cobalt/zinc/cadmium cation exporter | Membrane | 6.3 | 4.6E−04 |

| RS08895 | piuB | Iron uptake ABC transporter permease | Membrane | 5.6 | 6.4E−04 |

| RS08900 | piuC | Iron uptake ABC transporter permease | Membrane | 4.0 | 6.9E−03 |

| RS08905 | piuD | Iron uptake ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | Membrane | 4.3 | 7.7E−03 |

| RS08910 | piuA | Iron uptake ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | Membrane | 4.4 | 6.3E−03 |

| Other | |||||

| RS10785 | yfiA | Ribosome-associated factor Y | Cytoplasm | 4.8 | 2.3E−03 |

| RS10790 | comFC | Amidophosphoribosyl transferase/late competence protein | Cytoplasm | 4.1 | 2.3E−03 |

| RS00510 | purM | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole synthetase | Cytoplasm | 3.2 | 2.3E−04 |

| Unknown function | |||||

| RS01850 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Membrane | 4.5 | 5.2E−03 | |

| RS01860 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Membrane | 4.5 | 2.1E−03 | |

| RS03400 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Membrane | 3.2 | 1.1E−02 | |

| RS06730 | Hypothetical XRE family transcriptional regulator | Cytoplasm | 4.2 | 1.4E−02 | |

| RS06735 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Membrane | 4.6 | 1.3E−03 | |

| RS08115 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Membrane | 6.2 | 4.8E−04 | |

| RS10370 | Hypothetical CAAX self-immunity protease | Membrane | 3.7 | 2.0E−02 | |

| RS10375 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Membrane | 5.0 | 2.3E−03 | |

| RS10380 | Hypothetical membrane protein | Membrane | 6.2 | 1.3E−03 | |

| RS10385 | Hypothetical XRE family transcriptional regulator | Cytoplasm | 4.2 | 1.1E−02 | |

| RS10390 | Hypothetical protein | Unknown | 5.3 | 2.6E−03 |

The localization of ST3 proteins encoded by DE genes was predicted using pSORTb.

ST3 genes with an FC in expression of >3, a Padj of <0.05, and no change in expression in 7A9-treated mice are shown.

Expression of bolded genes was confirmed by RT-qPCR.

PTS, phosphotransferase.

TABLE 2.

Functional grouping of ST3 genes downregulated in the NP of 1E2-treated mice

| Gene function and gene | Gene name | Descriptiond | Localizationa | FC in expressionb | Padj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative/general stress response | |||||

| RS07455c | dpr | Dps-like peroxide resistance protein | Cytoplasm | −4.1 | 5.9E−06 |

| RS08550 | General stress protein 24 | Cytoplasm | −3.0 | 1.7E−02 | |

| RS10835 | General stress protein 781 (secreted 45-kDa protein) | Cytoplasm | −3.9 | 1.5E−06 | |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | |||||

| RS02180 | phaB | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | Cytoplasm | −3.8 | 1.7E−07 |

| RS02205 | fabD | ACP S-malonyltransferase | Cytoplasm | −3.8 | 2.5E−07 |

| Other functions | |||||

| RS01795 | kdgK | 2-Keto-3-deoxygluconate kinase | Cytoplasm | −3.1 | 2.3E−03 |

| RS01825 | PTS mannose/fructose/sorbose/N-acetylgalactosamine transporter subunit IIC | Membrane | −3.1 | 4.4E−02 | |

| RS01830 | manZ | Putative PTS N-acetylglucosamine transporter subunit IIBC | Membrane | −4.7 | 2.0E−02 |

| RS03780 | bioY | Biotin synthase | Membrane | −4.2 | 8.4E−06 |

| RS05695 | phpA | Pneumococcal histidine triad protein A | Unknown | −3.5 | 3.1E−08 |

The localization of ST3 proteins encoded by DE genes was predicted using pSORTb.

ST3 genes with an FC in expression of ≤3, a Padj of <0.05, and no change in expression in 7A9-treated mice are shown.

Expression of bolded genes was confirmed by RT-qPCR.

CoA, coenzyme A; ACP, acyl carrier protein; PTS, phosphotransferase.

Confirmation of gene expression changes by RT-qPCR.

To confirm the gene expression changes identified by RNA-seq, the same MAb treatment and colonization protocols were used for ex vivo reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) experiments, which were performed with RNA prepared from NP lavage fluid obtained from 1E2-, 5F6-, or control MAb-treated mice at 1 and 24 h postcolonization. For these experiments, we selected functionally diverse genes, some of which were upregulated by 1E2 and some of which were downregulated by 1E2. Relative to their expression in control MAb-treated mice, there were no significant changes in expression of the genes examined in 1E2- or 5F6-treated mice at 1 h postcolonization (Fig. 1C to J, 1 h). However, at 24 h postcolonization, relative to the gene expression by bacteria from control MAb-treated mice, the bacteria from 1E2-treated mice exhibited significantly increased expression of three transcription factors (deoR, RS06730, and merR), a carbohydrate transporter (malC), and an iron uptake gene (piuB), confirming our RNA-seq findings (Fig. 1F to J). We also confirmed that bacteria from 1E2-treated mice exhibited significantly decreased expression of fabD, phaB, and dpr at 24 h postcolonization relative to the expression of these genes by bacteria from control MAb-treated mice (Fig. 1C to E). 5F6, which binds a different PPS3 epitope than 1E2 (25) and did not reduce NP colonization, had no effect on expression of any gene tested by RT-qPCR relative to the gene expression by bacteria in control MAb-treated mice at 24 h postcolonization. Hence, 1E2 manifested a unique, specific ability to induce changes in ST3 gene expression that was not simply a function of its PPS3 specificity (Fig. 1C to J, 24 h). Given that 1E2 Fab fragments did not reduce ST3 colonization, we performed a set of RT-qPCR experiments with Fab fragments of 1E2 to examine the need for divalent binding on ST3 gene expression during colonization. Fab fragments had little effect on expression of dpr, piuB, and comX, while the effects of F(ab′)2 fragments were similar to those of whole 1E2 (Fig. 1E and F and S2C). Taken together, these data confirm that 1E2 exerts a direct effect on ST3 gene expression during colonization that is a function of its PPS3 specificity and that requires divalent binding.

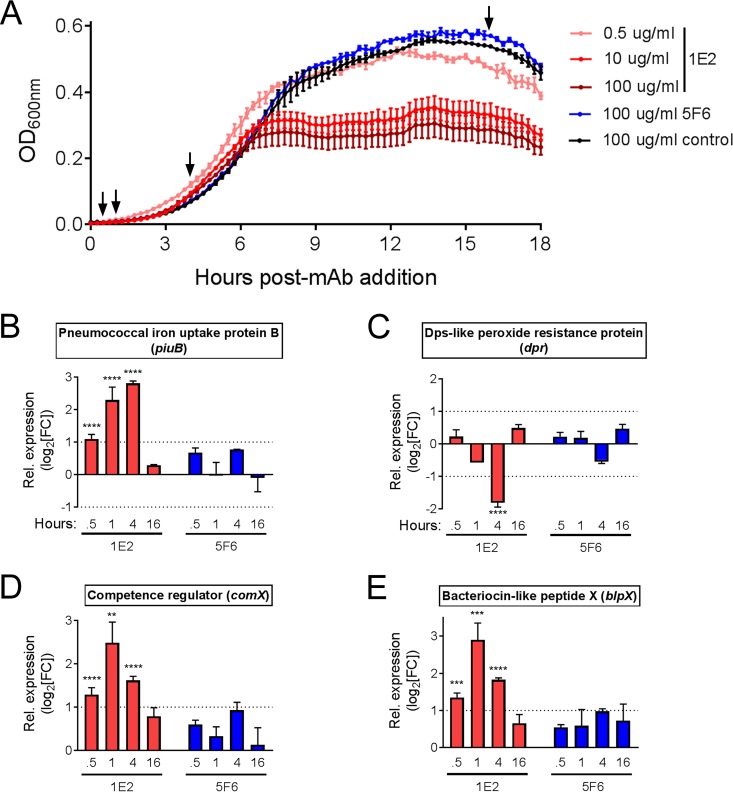

Dose-dependent changes in ST3 growth kinetics in the presence of 1E2 in vitro.

Using the in vivo gene expression data to guide our experiments, we investigated the effect of 1E2 on ST3 growth and physiology in vitro. First, we grew ST3 in the presence of 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb and found that 1E2 induced mid-log-stage arrest of bacterial growth at concentrations of ≥5 μg/ml, whereas 5F6 and the control MAb had no effect on growth (Fig. 2A). Next, we analyzed the expression of several genes whose expression was either altered during NP colonization (piuB, dpr, fabD, malC, RS06730) or previously shown to be altered by 1E2 in vitro (blpX, comX) (23) during early log, mid-log, and stationary growth phases in the presence of 10 μg/ml 1E2, 5F6, or control MAb. Compared to the expression achieved with the control MAb, 1E2 increased expression of piuB, blpX, and comX and decreased expression of dpr, whereas 5F6 had no significant effect on expression of any gene examined at any time point (Fig. 2B to E). The 1E2-induced increases in blpX and comX expression exhibited similar kinetics, with peak induction occurring at 1 h after treatment (Fig. 2D and E), whereas piuB induction increased over time and peaked at 4 h after treatment (Fig. 2B). The 1E2-mediated decrease in dpr exhibited kinetics similar to those seen with piuB, with the lowest expression occurring at 4 h after treatment (Fig. 2C). None of the genes examined exhibited significant changes in expression at stationary phase (Fig. 2B to E, 16 h), and expression of fabD, malC, and RS06730 was not significantly changed at any time examined (data not shown). These data are in agreement with those of previous work showing that 1E2 induces bacteriocin and competence gene expression in vitro (23) and suggest a role for piuB and dpr in the 1E2-mediated decrease in ST3 growth.

FIG 2.

1E2 induces ST3 growth arrest and alters piuB and dpr expression in vitro. (A) ST3 bacteria were incubated with the indicated amounts of 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb. Growth was monitored over 18 h and is shown as OD600 values. The results of a representative experiment from three independent experiments with similar results are shown. Arrows indicate the times at which samples were collected for RT-qPCR analysis of gene expression and for which the results are shown in panels B to E. (B to E) The fold change in expression of the indicated genes in 1E2- or 5F6-treated bacteria relative to that in the control MAb-treated bacteria was determined by RT-qPCR at the indicated times post-MAb addition. For relative expression values of >2 or <−2, P values for the differences in expression relative to that in control MAb-treated mice were determined by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test of nontransformed FC values at the same time points. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Data are from two independent experiments using three samples per condition per experiment.

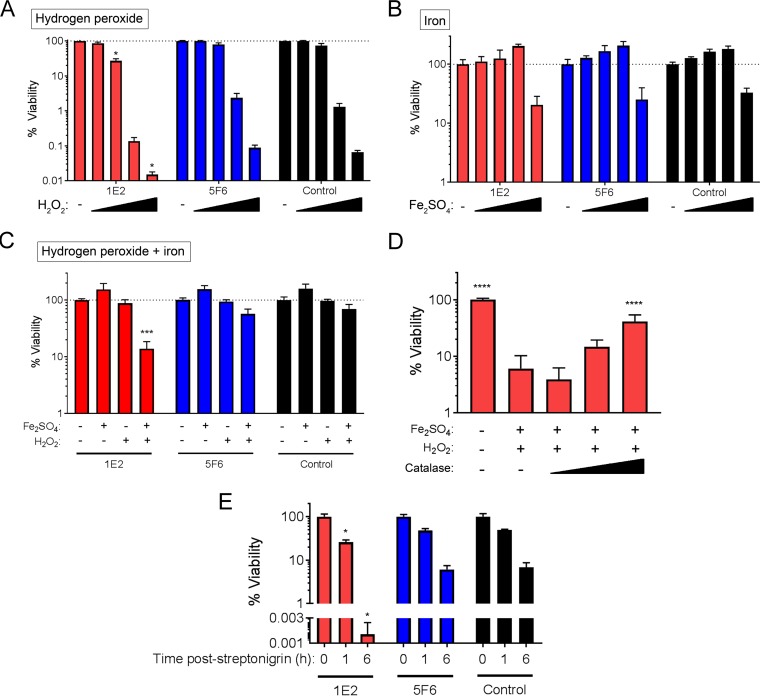

1E2 increases bacterial sensitivity to oxidative stress.

The reaction of ferrous iron with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) increases oxidative stress due to the production of toxic hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction. Our data showing upregulation of piuBCDA, coupled with downregulation of the oxidoprotective gene, dpr, suggested that increased uptake of iron and concomitant increases in oxidative stress may contribute to 1E2-induced colonization reduction and in vitro growth arrest. To test this hypothesis, we incubated ST3 with combinations of MAbs, iron (Fe2SO4), and H2O2 and quantified the number of viable CFU after 3 h. Compared to the effect of the control MAb, neither 1E2 nor 5F6 affected bacterial viability in the presence of Fe2SO4 alone (at concentrations up to 20 mM) (Fig. 3A). However, compared to the effect of the control MAb, 1E2 enhanced bacterial sensitivity to H2O2 alone (2 to 16 mM) (Fig. 3B). Addition of 1 mM Fe2SO4 further enhanced the sensitivity of 1E2-treated bacteria to 2 mM H2O2, whereas the combination of Fe2SO4 and H2O2 had little effect on 5F6- or control MAb-treated bacteria (Fig. 3C). To determine if the decrease in ST3 viability with the combination of 1E2, Fe2SO4, and H2O2 was due to increased oxidative stress, we added increasing amounts of catalase to bacteria in the presence of Fe2SO4, H2O2, and 1E2. Catalase protected ST3 from the toxic effects of 1E2, Fe2SO4, and H2O2 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). Finally, we examined the sensitivity of 1E2-treated bacteria to streptonigrin, an antibiotic that requires iron for its bactericidal activity and that is used as a surrogate for interrogating intracellular iron levels in bacteria (26–28). 1E2-treated bacteria were significantly more sensitive to streptonigrin than bacteria treated with the control MAb, whereas 5F6-treated bacteria were not (Fig. 3E). Together, these data show that treatment of ST3 with 1E2 increases iron import into ST3 and enhances its sensitivity to iron-mediated oxidative stress.

FIG 3.

1E2 enhances ST3 sensitivity to iron-induced oxidative stress. ST3 bacteria were mixed with 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb in C+Y medium. (A) MAb-mediated sensitivity to H2O2 was determined by mixing ST3 and the MAbs with 2 to 16 mM H2O2. (B) MAb-mediated sensitivity to iron was determined by mixing ST3 and the MAbs with 1 to 20 mM Fe2SO4. (C) MAb-mediated sensitivity to the combination of iron and H2O2 was determined by mixing ST3 and the MAbs with 1 mM Fe2SO4 and 2 mM H2O2. (D) The ability of catalase to rescue 1E2-mediated sensitivity to iron and H2O2 was determined by adding 0.1 to 10 units of catalase to mixtures of 1E2, iron, and H2O2, as described in the legend to panel C. (E) MAb-mediated sensitivity to streptonigrin was determined by incubating ST3 and MAbs with 19 μM streptonigrin for the indicated times before plating for determination of the number of viable CFU. For panels A to D, mixtures were incubated for 3 h before plating for determination of the number of viable CFU. P values for the differences compared to the results obtained with the control MAb under the same treatment conditions (A to C and E) or the 0 mM catalase condition (D) were determined by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. All results are expressed as percent viability calculated relative to the viability under the MAb-only condition within each MAb group. All results are from two to three independent experiments with three samples per condition per experiment.

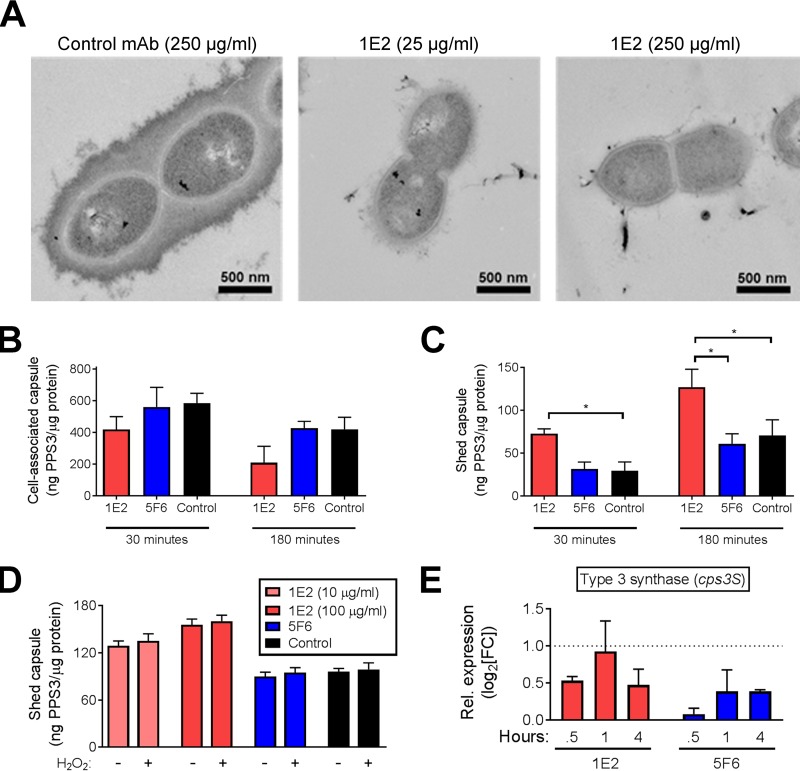

1E2 induces capsule shedding.

The in vivo and in vitro data presented herein show that 1E2 treatment induces profound changes in bacterial physiology and alters expression of many genes encoding proteins predicted to localize to the cell envelope (Tables S1 and S2). To determine if these changes translate to morphological changes, we performed electron microscopy (EM) on ST3 after incubation with increasing amounts of 1E2. Our results show very little cell-associated capsule on the bacterial surface after 1 h of incubation with 25 μg/ml 1E2 and even less after 1 h of incubation with 250 μg/ml 1E2, whereas control MAb-treated bacteria appeared to have intact, thick capsules (Fig. 4A). To determine if 1E2 binding induced capsule shedding, we quantified shed and cell-associated PPS3 in the supernatants and lysates, respectively, of 1E2-, 5F6-, and control MAb-treated bacteria. 1E2-treated bacteria shed significantly more PPS3 and had less cell-associated PPS3 than control MAb-treated bacteria after 30 min (Fig. 4B and C, 30 min). Although we observed increases in shed PPS3 and reductions in cell-associated PPS3 with all MAbs over time, 1E2-treated bacteria still shed significantly more PPS3 and had less cell-associated PPS3 than control MAb-treated bacteria after 3 h of coincubation (Fig. 4B and C, 3 h). Coincubation of ST3 with 5F6 had no effect on shed or cell-associated PPS3 compared to the effect of coincubation of ST3 with the control MAb at either time (Fig. 4B and C). We next determined if increases in oxidative stress trigger capsule shedding in 1E2-treated bacteria and found that addition of H2O2 had no effect on capsule shedding, even in the presence of 1E2 (Fig. 4D). Finally, we sought changes in expression of cps3S, which encodes the synthase responsible for ST3 capsule production, by RT-qPCR and found that neither 1E2 nor 5F6 affected cps3S expression compared to the effect of the control MAb after up to 4 h (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that 1E2 induces capsule shedding and suggest that this is not due to changes in cps3 gene expression or increases in oxidative stress.

FIG 4.

1E2 triggers ST3 capsule shedding in vitro. (A) Electron micrographs of ST3 following 3 h of incubation with the indicated amounts of 1E2 or control MAb in PBS. Representative images from a single experiment are shown. (B and C) A total of 104 bacteria were incubated with 100 μg/ml of the indicated MAbs for 30 min or 3 h in PBS. Shed (C) and cell-associated (B) capsules were quantified by ELISA. (D) Bacteria were incubated with MAbs in the presence or absence of H2O2 for 3 h, and capsule shedding was quantified by ELISA. (E) Expression of the ST3 capsule synthase gene (cps3S) was determined by RT-qPCR after 1 h of incubation with 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb in PBS. Results are shown as the level of expression relative to that achieved with control MAb treatment. For panels B to D, data are presented as the number of nanograms of capsule (PPS3) per microgram of protein in the corresponding cell pellets and are from two to three independent experiments using three samples per condition per experiment. *, P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that 1E2 alters ST3 gene expression in vivo and induces direct changes to ST3 physiology in vitro. These changes are host independent, as they are mediated by F(ab′)2 fragments in vivo and occur in the absence of any host factors in vitro. RNA-seq analysis identified 43 genes with increased expression and 10 with decreased expression in bacteria obtained from 1E2-treated mice relative to their expression in bacteria obtained from mice treated with the controls. These data extend to an in vivo NP colonization model previous work that demonstrated that 1E2 can alter ST3 gene expression in vitro (23). To our knowledge, the finding that antibody binding can lead to an alteration in gene expression in vivo is novel, revealing a heretofore unrecognized mechanism of antibody action.

Our data demonstrate that 1E2 altered expression of several ST3 genes that induce or respond to oxidative stress, including the Dps-like peroxide resistance gene, dpr, and the pneumococcal iron uptake (Piu) operon, piuBCDA. The Piu complex is required for optimal pneumococcal growth, colonization, and virulence in mice (26, 29, 30). Due to the large amount of H2O2 produced during normal pneumococcal growth, iron acquisition is intimately linked to oxidative stress, whereby intracellular iron can react with H2O2 to form toxic hydroxyl radicals. Therefore, proper regulation of iron import, H2O2 catabolism, and other detoxification mechanisms is critical for pneumococcal resistance to oxidative stress (29, 31, 32). One of the most well characterized mechanisms by which pneumococci cope with iron-induced oxidative stress is through the activity of Dpr, which is expressed in response to intracellular iron and protects bacteria from oxidative damage by sequestering iron (24, 33, 34).

1E2 decreased dpr expression during colonization and in vitro growth and enhanced ST3 sensitivity to iron-mediated oxidative stress. In this regard, the effects of 1E2 on ST3 mirror the finding of another group that an ST2 Δdpr deletion mutant was more sensitive to iron and streptonigrin in vitro and had a reduced ability to colonize the NP of mice (24). Since iron and oxidative stress increase dpr expression (27, 35), it may seem paradoxical that 1E2 increases iron uptake through piuBCDA induction, yet it decreases dpr expression. However, H2O2 also increases piuB expression and decreases dpr expression in ST2 strains (36), and piu genes or their homologs are induced in several bacterial species in response to various stressors, including antibiotics, heat shock, and nutrient starvation (37–41). This suggests that piu upregulation may be part of a general response to stress or factors that reduce the capacity for bacterial growth. Thus, our data suggest that 1E2-mediated enhancement of oxidative stress may resemble the response to other conditions that compromise bacterial viability during growth or infection. This is consistent with our finding that 1E2 inhibits ST3 growth in vitro and in vivo.

Fifty-three percent of proteins encoded by genes with significantly altered expression in 1E2-treated mice are predicted to localize to the pneumococcal surface; this is nearly double the proportion of surface proteins encoded in the ST3 genome (28%). Since 1E2 also binds a unique PPS3 determinant that is distinct from that recognized by 5F6 or 7A9 (19, 25), we determined the effect of 1E2 binding on ST3 morphology. 1E2 triggered rapid shedding of the ST3 capsule within 30 min in vitro. Regulated capsule shedding is required for pneumococcal transition from colonization to invasion (42, 43). Accordingly, unencapsulated ST3 strains do not colonize mice, and strains with reduced capsule have a lower invasive potential (44). Capsule shedding also occurs during pneumococcal quorum sensing and biofilm growth, two conditions under which the local bacterial density is high (45).

Antibody-induced agglutination of ST6B and ST23F pneumococci was shown to reduce colonization in a divalent binding-dependent manner (46, 47). As shown previously (22) and herein, the 1E2-mediated reduction in colonization required divalent antibody binding, e.g., binding of whole antibody or F(ab′)2 fragments. In addition, in a single in vivo experiment, 1E2 F(ab′)2 fragments and whole antibody (1E2) induced similar changes in expression of the dpr, piuB, and comX genes, whereas monovalent Fab fragments had no effect on ST3 colonization or gene expression. We did not evaluate capsule shedding in vivo. Nonetheless, the ability of 1E2 to agglutinate ST3 in vitro (18, 22, 23) and the requirement of divalent 1E2 for colonization reduction in vivo lead us to hypothesize that 1E2 may mediate its effect in the NP via agglutination, which in turn may promote capsule shedding and induce changes in gene expression. In other words, our observations may reflect downstream effects of 1E2-mediated ST3 agglutination, possibly quorum sensing, as 1E2 was previously shown to induce ST3 agglutination and initiate a second wave of quorum sensing in vitro (23). Consistent with this hypothesis, capsule loss preceded the effects of 1E2 on ST3 growth and gene expression in vitro; we observed capsule shedding 30 min after 1E2 treatment and gene expression changes and growth arrest 1 to 4 h later. Lending further support to this concept, as noted above, capsule-binding antibodies that agglutinate other STs mediate reduced colonization (46–49). Further work is needed to establish whether or not antibody-mediated agglutination of other STs also affects homologous ST gene expression in vivo.

1E2 also affected expression of other ST3 genes during colonization. It increased expression of a number of carbohydrate-related genes, particularly those involved in acquisition of large polysaccharides, such as sialic acid and maltodextrin, and the processing of glucose and galactose. This is consistent with the hypothesis that bacteria may respond to 1E2-induced capsule loss by upregulating carbohydrate transport and processing genes to produce new capsule or capsule subunits. This is plausible. ST3 capsule production is linked to the intracellular concentrations of glucose and glucuronic acid, the two monosaccharides that compose PPS3 (50–53). However, more work is needed to determine the relationships between capsule shedding, gene expression changes, and sensitivity to iron-mediated oxidative stress.

The concentration of 1E2 needed to induce changes in ST3 growth, gene expression, capsule shedding, and sensitivity to oxidative stress in vitro was higher than the previously measured concentration of 1E2 in the NP of uninfected mice at 24 h postadministration (22). We did not measure the concentration of 1E2 in the NP of mice in this study, but the NP environment is vastly different from that of an in vitro experiment. Mahdi et al. described gene expression patterns that differed in the NP and blood of ST4- and ST6-infected mice (54); 62 genes were differentially expressed in the NP and linked to the transition from colonization to invasion. Of these genes, dpr and five others were also differentially expressed in 1E2-treated mice, albeit in the opposite direction. For example, Mahdi et al. found that dpr expression was higher in the NP than in the blood (54), whereas it decreased in 1E2-treated, ST3-infected mice in our study. These observations are consistent with the idea that 1E2 inhibits the normal transition from colonization to invasion.

1E2 had a specific effect on ST3 gene expression that did not occur with other PPS3-binding MAbs, as shown in separate in vivo experiments by RT-qPCR for selected genes with 5F6. Furthermore, like the control MAb, 5F6 had no effect on bacterial growth, expression of piuB or dpr, sensitivity to oxidative stress, or capsule shedding in vitro. A prior study established that 1E2 and 5F6 mediate protection against ST3 pneumonia in mice by different mechanisms, requiring different host Fc receptors (which are required for 1E2 to protect against pneumonia) and effector molecules (18, 20). 1E2 and 5F6 also bind unique PPS3 trisaccharides (18, 25). Our data therefore provide further evidence that MAbs with different PPS3 specificity work in fundamentally different ways to protect against ST3 disease.

An important caveat to our findings is that the amount of bacteria in the NP of 1E2-treated mice was lower (103 to 104 CFU/mouse) than that in the NP of control mice, as 1E2 reduced the number of NP CFU, in agreement with previous findings (22). In addition, NP lavage specimens contained mixtures of bacterial and mouse cells, making it challenging to acquire sufficient bacterial RNA for comprehensive analysis. As a result, we obtained reliable expression data for just 86.1% (1,884/2,189) of the genes in the ST3 genome (strain OXC141; GenBank accession number FQ312027.1) after removal of genes with low read counts. Although we validated our findings of 1E2-altered gene expression in vivo in separate experiments using RT-qPCR, our RNA-seq data set may have underestimated the effects of 1E2 on bacterial gene expression during NP colonization.

Our discovery that a protective PPS3 MAb altered ST3 gene expression in vivo provides proof of concept that PPS3-binding antibodies can exert direct antibacterial effects. However, we recognize that more work is needed to determine if our findings apply to other PPS antibodies and STs. Nonetheless, the correlation between 1E2-induced gene expression changes and reduced ST3 NP colonization suggests that it may be feasible to develop antibody-based therapy against ST3 that works by altering bacterial metabolism and physiology. The fact that 1E2 reduces colonization in vivo, including as an F(ab′)2 fragment, and affects ST3 viability in vitro, where immune components are not present, highlights the promise that 1E2 and antibodies like it may hold as potential therapeutics for pneumococcal disease, particularly in vulnerable immunocompromised populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

The ST3 Streptococcus pneumoniae strain A66.1 (ST3; originally a gift from D. E. Briles) was grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 on Trypticase soy agar II with 5% sheep blood (BD Biosciences) or in Casamino Acids plus yeast extract (C+Y) broth without shaking. For mouse infections, ST3 was grown to early log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.1 to 0.2), washed once with PBS, and frozen in growth medium with 15% glycerol at −80°C until use. Frozen aliquots were thawed and washed twice with PBS immediately prior to use. For growth curve analysis, ST3 was grown to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.3 to 0.4) and diluted to an optical density (OD) of approximately 0.001. One hundred microliters of diluted culture was transferred to sterile, flat-bottom 96-well plates (Corning) and mixed with 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb (see below) at the concentrations indicated in the figures. The plates were sealed and incubated at 37°C, and the OD600 was recorded every 15 min on a VersaMax plate reader (Molecular Devices).

Mouse MAbs.

The derivation and biological activities of the PPS3 mouse IgG1(κ) monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9 and the PPS8 mouse IgG1 MAb 31B12, which was used as a specificity and isotype control, were previously described (18, 55). Antibody fragments were generated using a mouse IgG1 Fab and F(ab′)2 micropreparation kit (Thermo). For Fab generation, 250 μg 1E2 was digested for 4 h with immobilized ficin in the presence of 25 mM cysteine; for F(ab′)2 generation, 250 μg 1E2 was digested for 30 h with immobilized ficin in the presence of 4 mM cysteine. Undigested 1E2 was captured using protein A agarose beads, and Fab or F(ab′)2 fragments were collected in PBS. Proper fragment generation was verified by Coomassie blue staining. Equimolar amounts of F(ab′)2 and Fab fragments were tested for binding to PPS3 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (22), and no significant differences from the results obtained with whole 1E2 were observed (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material).

Mouse infections and organ burden assays.

Nasopharyngeal (NP) colonization with ST3 was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, 6- to 8-week-old female wild-type C57BL/6 mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were anesthetized with isoflurane and intranasally (i.n.) infected with 2 × 105 CFU of ST3 resuspended in a volume of 10 μl PBS. The actual number of ST3 bacteria administered was confirmed by plating the inoculum given to each mouse.

The numbers of CFU in the NP and lungs of MAb-treated and untreated mice were determined at 1 or 3 days postinfection. In some experiments, mice were passively immunized 2 h before infection by intraperitoneal injection of 20 μg of PPS3 MAbs (1E2, 5F6, and 7A9) or a PPS8 MAb (31B12) as an isotype and specificity control in a total volume of 100 μl PBS. For experiments using 1E2 fragments, mice were passively immunized via intranasal administration of 20 μg whole 1E2 or equimolar amounts of F(ab′)2 or Fab fragments 2 h before infection. To determine the numbers of NP CFU, mice were humanely killed, the trachea was cannulated and lavaged with 600 μl PBS, and lavage fluid was collected from the nares. The lavage fluid was vigorously vortexed to disrupt bacterial aggregates and serially diluted in PBS, and dilutions were plated in duplicate. To determine the numbers of lung CFU, the lungs were removed, weighed, and homogenized in 1 ml PBS using a BioSpec BeadBeater and 1-mm beads. Homogenates were serially diluted in PBS, and dilutions were plated in duplicate. Neat lung homogenate was plated to yield a limit of detection of 20 CFU/g for each mouse. The bacterial burdens in the NP and lungs were calculated from colony counts and are expressed as the number of CFU per lavage fluid sample or the number of CFU per gram of tissue, respectively. All experiments were performed 2 to 3 times on groups of 3 to 5 mice per experiment, as indicated in the figure legends. All mouse experiments were done in accordance with the guidelines and with the approval of the Animal Institute of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

RNA extraction.

To assess the effects of 1E2 on gene expression during colonization, we performed two independent immunization-infection-lavage experiments (experiments A and B) as described above. Both experiments were performed using groups of mice treated with 1E2, the control MAb, and PBS; experiment A included an additional group of mice treated with 7A9. For 1E2-, control MAb-, and PBS-treated mice, the numbers of NP CFU were similar to those in the colonization experiments whose results are shown in Fig. S1; as shown previously (22), the numbers of NP CFU for 7A9-treated mice were not significantly different from those for control MAb-treated mice (data not shown). Lavage fluid from groups of 6 to 8 mice were placed on ice, pooled, and centrifuged for 5 min at 7,000 × g and 4°C to collect cells (mouse and bacterial). For in vitro gene expression analysis, bacteria were collected and centrifuged as described above. NP lavage fluid or bacterial pellets were immediately resuspended in 200 μl preheated Max bacterial enhancement reagent (Thermo) and incubated at 95°C for 10 min. Crude lysates were added to 1.3 ml TRIzol reagent (Thermo) and further lysed using a BeadBeater (BioSpec) and 0.1-mm beads for 5 min. Lysates were mixed with 280 μl ice-cold chloroform and incubated at room temperature for 5 min before centrifugation for 15 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C. RNA was precipitated by mixing approximately 450 μl of the upper RNA-containing layer with 600 μl cold isopropanol and centrifugation for 10 min at 15,000 × g and 4°C. The RNA pellets were washed twice with 75% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in 50 μl diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated H2O.

RNA sequencing and alignment.

cDNA sequencing libraries were prepared using a Nugen Ovation RNA-seq system (v2) sample preparation kit in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 10 ng of total RNA was used for conversion to cDNA, which was then amplified and purified. Purified cDNA was sheared and size selected to remove large and small fragments. DNA was adenylated and ligated to Illumina sequencing adapters using a Kapa Hyper library preparation kit. Final libraries were quantified using a Kapa library quantification kit (Kapa Biosystems), a Qubit fluorometer (Life Technologies), and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2500 sequencer (v4 chemistry) using 2 × 125-bp cycles.

Reads were first aligned to the mouse mm10 genome using the STAR (v2.4.0c) program, and mouse reads were removed before proceeding with bacterial analysis. Reads mapping to rRNA were also removed using the SortMeRNA (v1.9) sequence analysis tool and the Rfam 5s/5.8s, Silva archaea and bacteria 16S and 23S, and Silva eukaryotic 18S/28S databases. The remaining reads were aligned to the ST3 genome (strain OXC141; GenBank accession number FQ312027.1) using the Burrows-Wheeler aligner (v0.7.12), and genes were quantified using FeatureCounts from the subread package (v1.4.3-p1).

Analysis of differential gene expression.

The total read counts mapping to the ST3 genome in the MAb and PBS treatment groups ranged from 8.1 × 105 to 5.5 × 106 in experiment A and 1.1 × 105 to 3.0 × 105 in experiment B. Prior to differential expression analysis, genes with low levels of expression (<5 reads for all samples or normalized gene expression of <7) were removed from all data sets, allowing us to reliably examine the expression of 86.1% of genes (1,884/2,189) in the ST3 genome (strain OXC141; GenBank accession number FQ312027.1) (56). The control MAb- and PBS-treated groups were originally included under independent control conditions. No DE genes were identified between the control MAb- and PBS-treated groups (Data Set S2), and the control MAb- and PBS-treated groups clustered closely together by principal component analysis (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the control MAb- and PBS-treated groups were combined into a single control group to increase the statistical power. Comparison of gene expression in 1E2-, 7A9-, and control-treated samples was performed using the DESeq2 program with adjustment for batch effects (57). The genes in ST3 bacteria from 1E2-treated mice with genes significantly DE relative to their expression in bacteria from the combined control group were identified using a cutoff of a false discovery rate-adjusted P value (Padj) of <0.05 (58) and a ∣fold change∣ in expression of >3.0. All DE genes were included on a heatmap based on relative expression (normalized expression − average of the normalized expression for each gene). Clustering of genes and treatment groups was done on the basis of the Euclidean distance. A principal component analysis was performed using regularized-logarithm transformation values of the top 500 most variable genes, adjusted for batch effects (57).

Functional classification of genes with a ∣FC∣ in expression of >2 in 1E2-treated mice relative to their expression in the controls was performed using the eggNOG-mapper tool (59). For genes with a ∣FC∣ in expression of >3 in 1E2-treated mice relative to that in the controls, COG classes and functions identified by the eggNOG-mapper tool were manually curated and either verified or amended where necessary using results from analysis with the PaperBLAST program (60). The predicted localization of all proteins encoded by nonpseudogenes in the entire ST3 genome was determined using the PSORTb (v3.0.2) program and is shown in Data Set S3 (61). For surface protein enrichment analysis, the total number of proteins encoded by DE ST3 genes predicted to localize to the membrane and cell wall was compared to that in the entire ST3 genome using Fisher's exact test, and an exact two-tailed P value was calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

To analyze the effects of 1E2 and 5F6 on expression of selected genes identified by RNA-seq, mice were immunized with 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb, infected, and lavaged as described above. To analyze the effects of 1E2 fragments on expression of selected genes identified, mice were treated with whole 1E2 or the F(ab′)2 or Fab fragment, infected, and lavaged as described above. To analyze expression of selected genes during in vitro growth, bacteria were grown as described above, diluted to a starting OD of ∼0.01, and incubated with 1E2, 5F6, or the control MAb for the times indicated in the figure legends. For cps3S expression, bacteria were incubated in PBS for 30 min or 3 h as described below. cDNA was synthesized from 20 ng total RNA, prepared as described above using a SuperScript IV Vilo with ezDNase kit (Thermo) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was performed using PowerUp SYBR green (Life Technologies) mixed with 10 ng cDNA and 600 nM the primers indicated in Table S4. Amplification was performed on a StepOne Plus real-time PCR system (Life Technologies) using the following conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 s and 60°C for 30 s. Melt curve analysis and gel electrophoresis confirmed amplification of a single product for all genes examined (data not shown). Relative expression of genes in 1E2- or 5F6-treated bacteria was determined by the ΔΔCT threshold cycle (CT) method using the 16S rRNA gene as an internal control and control MAb-treated bacteria as the reference.

Iron, hydrogen peroxide, and streptonigrin sensitivity.

To assess the sensitivities of MAb-treated bacteria to iron, H2O2, and streptonigrin, frozen aliquots of bacteria prepared as described above were washed with PBS and diluted to approximately 10,000 CFU/ml in PBS. The bacteria were then incubated with each MAb (100 μg/ml) in the presence of Fe2SO4 (1 to 20 mM) or H2O2 (2 to 16 mM) for 3 h or streptonigrin (19 μM) for 1 or 6 h. Some experiments were performed using 1 mM Fe2SO4 and 2 mM H2O2. After incubation, the mixtures were serially diluted and plated to determine the number of viable CFU. For each MAb condition, viable bacteria in samples using MAb alone were counted and the result was set to 100% viability. For all other conditions within each MAb group, percent viability was calculated relative to that for the MAb-only control. None of the MAbs had an independent effect on bacterial viability in PBS over the duration of the experiments (data not shown).

Capsule shedding and cell-associated capsule assays.

To evaluate the levels of shed and cell-associated capsule, frozen aliquots of bacteria prepared as described above were diluted to approximately 50,000 CFU/ml and incubated with MAbs in 200 μl PBS for 30 min or 3 h, as indicated in the figure legends. Where indicated, H2O2 was added (final concentration, 1 mM). Following incubation, bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants were decanted, cleared using a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter, and stored at −20°C until analysis. An aliquot of filtered supernatant was plated to confirm sterility. Pellets were washed three times with PBS, resuspended in 1 ml PBS, and lysed via sonication. Protein content was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein kit (Pierce). Supernatants and cell lysates were diluted (1:100 for lysates; 1:1,000 for supernatants) and used to directly coat high-binding 96-well ELISA plates (Corning) overnight. Separate wells were coated with PPS3 (ATCC 169-X) to allow for quantitation by use of a standard curve. On the following day, the plates were blocked for 1 h using PBS–2% bovine serum albumin and then incubated with a PPS3-specific human IgM MAb, A7 (62), for 1 h. The plates were washed three times in PBS–0.2% Tween 20, incubated with anti-human IgM-alkaline phosphatase (1:1,000; catalog number 2020-04; Southern Biotech) for 1 h, and developed with the p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Pierce) for 20 min, and the OD405 for each well was recorded. Capsule amounts were calculated using a standard curve of PPS3 and normalized to the protein content in the lysates.

Electron microscopy.

Bacteria were incubated with 1E2 or the control MAb in PBS at the concentrations indicated above for 3 h. Fixation, embedding, sectioning, and staining of the bacterial pellets were performed exactly as described previously by Hammerschmidt et al. (42). Samples were examined with a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV.

Accession number(s).

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE113991.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the New York Genome Center for generating the high-quality RNA sequencing data and for the project support provided by Catherine Reeves and Heather Geiger. We thank Leslie Gunther Cummins and the Analytical Imaging Facility of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine for their expertise and assistance with EM experiments. We thank Rachelle Babb for her expertise and assistance with mouse infection experiments.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI123654 and R01AG045044 to L.P., R21CA202529 to T.W., and T32AI070117 to C.R.D. (principal investigator, Kami Kim). The Analytical Imaging Facility of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine is supported by P30CA013330.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00300-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews NJ, Waight PA, Burbidge P, Pearce E, Roalfe L, Zancolli M, Slack M, Ladhani SN, Miller E, Goldblatt D. 2014. Serotype-specific effectiveness and correlates of protection for the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a postlicensure indirect cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 14:839–846. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70822-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juergens C, Patterson S, Trammel J, Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Cooper D, Gurtman A, Gruber WC, Scott DA, Dagan R. 2014. Post hoc analysis of a randomized double-blind trial of the correlation of functional and binding antibody responses elicited by 13-valent and 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and association with nasopharyngeal colonization. Clin Vaccine Immunol 21:1277–1281. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00172-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero-Steiner S, Frasch CE, Carlone G, Fleck RA, Goldblatt D, Nahm MH. 2006. Use of opsonophagocytosis for serological evaluation of pneumococcal vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol 13:165–169. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.2.165-169.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simell B, Auranen K, Kayhty H, Goldblatt D, Dagan R, O'Brien KL, Pneumococcal Carriage Group. 2012. The fundamental link between pneumococcal carriage and disease. Expert Rev Vaccines 11:841–855. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. 2004. New concepts in antibody-mediated immunity. Infect Immun 72:6191–6196. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6191-6196.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivanov MI, Hill J, Bliska JB. 2014. Direct neutralization of type III effector translocation by the variable region of a monoclonal antibody to Yersinia pestis LcrV. Clin Vaccine Immunol 21:667–673. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00013-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaRocca TJ, Holthausen DJ, Hsieh C, Renken C, Mannella CA, Benach JL. 2009. The bactericidal effect of a complement-independent antibody is osmolytic and specific to Borrelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:10752–10757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901858106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levinson KJ, Baranova DE, Mantis NJ. 2016. A monoclonal antibody that targets the conserved core/lipid A region of lipopolysaccharide affects motility and reduces intestinal colonization of both classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae biotypes. Vaccine 34:5833–5836. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matos Baltazar L, Nakayasu ES, Sobreira TJ, Choi H, Casadevall A, Nimrichter L, Nosanchuk JD. 2016. Antibody binding alters the characteristics and contents of extracellular vesicles released by Histoplasma capsulatum. mSphere 1(2):e00085-. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00085-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClelland EE, Nicola AM, Prados-Rosales R, Casadevall A. 2010. Ab binding alters gene expression in Cryptococcus neoformans and directly modulates fungal metabolism. J Clin Invest 120:1355–1361. doi: 10.1172/JCI38322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Lazinski DW, Camilli A. 2017. Immunity provided by an outer membrane vesicle cholera vaccine is due to O-antigen-specific antibodies inhibiting bacterial motility. Infect Immun 85:e00626-. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00626-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prados-Rosales R, Carreno L, Cheng T, Blanc C, Weinrick B, Malek A, Lowary TL, Baena A, Joe M, Bai Y, Kalscheuer R, Batista-Gonzalez A, Saavedra NA, Sampedro L, Tomas J, Anguita J, Hung SC, Tripathi A, Xu J, Glatman-Freedman A, Jacobs WR Jr, Chan J, Porcelli SA, Achkar JM, Casadevall A. 2017. Enhanced control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis extrapulmonary dissemination in mice by an arabinomannan-protein conjugate vaccine. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006250. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horacio AN, Silva-Costa C, Lopes JP, Ramirez M, Melo-Cristino J, Portuguese Group for the Study of Streptococcal Infections. 2016. Serotype 3 remains the leading cause of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults in Portugal (2012–2014) despite continued reductions in other 13-valent conjugate vaccine serotypes. Front Microbiol 7:1616. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slotved HC, Dalby T, Harboe ZB, Valentiner-Branth P, Casadevante VF, Espenhain L, Fuursted K, Konradsen HB. 2016. The incidence of invasive pneumococcal serotype 3 disease in the Danish population is not reduced by PCV-13 vaccination. Heliyon 2:e00198. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moraga-Llop F, Garcia-Garcia JJ, Diaz-Conradi A, Ciruela P, Martinez-Osorio J, Gonzalez-Peris S, Hernandez S, de Sevilla MF, Uriona S, Izquierdo C, Selva L, Campins M, Codina G, Batalla J, Esteva C, Dominguez A, Munoz-Almagro C. 2016. Vaccine failures in patients properly vaccinated with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Catalonia, a region with low vaccination coverage. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35:460–463. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi EH, Zhang F, Lu YJ, Malley R. 2016. Capsular polysaccharide (CPS) release by serotype 3 pneumococcal strains reduces the protective effect of anti-type 3 CPS antibodies. Clin Vaccine Immunol 23:162–167. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00591-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabrizio K, Manix C, Tian HJ, van Rooijen N, Pirofski LA. 2010. The efficacy of pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide-specific antibodies to serotype 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae requires macrophages. Vaccine 28:7542–7550. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian H, Weber S, Thorkildson P, Kozel TR, Pirofski LA. 2009. Efficacy of opsonic and nonopsonic serotype 3 pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide-specific monoclonal antibodies against intranasal challenge with Streptococcus pneumoniae in mice. Infect Immun 77:1502–1513. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01075-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian HJ, Groner A, Boes M, Pirofski LA. 2007. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine-mediated protection against serotype 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae in immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun 75:1643–1650. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01371-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber S, Tian HJ, van Rooijen N, Pirofski LA. 2012. A serotype 3 pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide-specific monoclonal antibody requires Fc gamma receptor III and macrophages to mediate protection against pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. Infect Immun 80:1314–1322. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06081-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber SE, Tian HJ, Pirofski LA. 2011. CD8(+) cells enhance resistance to pulmonary serotype 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice. J Immunol 186:432–442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle CR, Pirofski LA. 2016. Reduction of Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization and dissemination by a nonopsonic capsular polysaccharide antibody. mBio 7:e02260-. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02260-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yano M, Gohil S, Coleman JR, Manix C, Pirofski LA. 2011. Antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide enhance pneumococcal quorum sensing. mBio 2:e00176-. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00176-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua CZ, Howard A, Malley R, Lu YJ. 2014. Effect of nonheme iron-containing ferritin Dpr in the stress response and virulence of pneumococci. Infect Immun 82:3939–3947. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01829-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parameswarappa SG, Reppe K, Geissner A, Menova P, Govindan S, Calow AD, Wahlbrink A, Weishaupt MW, Monnanda BP, Bell RL, Pirofski LA, Suttorp N, Sander LE, Witzenrath M, Pereira CL, Anish C, Seeberger PH. 2016. A semi-synthetic oligosaccharide conjugate vaccine candidate confers protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 3 infection. Cell Chem Biol 23:1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown JS, Gilliland SM, Ruiz-Albert J, Holden DW. 2002. Characterization of pit, a Streptococcus pneumoniae iron uptake ABC transporter. Infect Immun 70:4389–4398. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4389-4398.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulijasz AT, Andes DR, Glasner JD, Weisblum B. 2004. Regulation of iron transport in Streptococcus pneumoniae by RitR, an orphan response regulator. J Bacteriol 186:8123–8136. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.8123-8136.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeowell HN, White JR. 1982. Iron requirement in the bactericidal mechanism of streptonigrin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 22:961–968. doi: 10.1128/AAC.22.6.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honsa ES, Johnson MD, Rosch JW. 2013. The roles of transition metals in the physiology and pathogenesis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:92. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown JS, Gilliland SM, Holden DW. 2001. A Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenicity island encoding an ABC transporter involved in iron uptake and virulence. Mol Microbiol 40:572–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pericone CD, Park S, Imlay JA, Weiser JN. 2003. Factors contributing to hydrogen peroxide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae include pyruvate oxidase (SpxB) and avoidance of the toxic effects of the Fenton reaction. J Bacteriol 185:6815–6825. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.23.6815-6825.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yesilkaya H, Andisi VF, Andrew PW, Bijlsma JJ. 2013. Streptococcus pneumoniae and reactive oxygen species: an unusual approach to living with radicals. Trends Microbiol 21:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto Y, Poole LB, Hantgan RR, Kamio Y. 2002. An iron-binding protein, Dpr, from Streptococcus mutans prevents iron-dependent hydroxyl radical formation in vitro. J Bacteriol 184:2931–2939. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2931-2939.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsou CC, Chiang-Ni C, Lin YS, Chuang WJ, Lin MT, Liu CC, Wu JJ. 2008. An iron-binding protein, Dpr, decreases hydrogen peroxide stress and protects Streptococcus pyogenes against multiple stresses. Infect Immun 76:4038–4045. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00477-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ong CL, Potter AJ, Trappetti C, Walker MJ, Jennings MP, Paton JC, McEwan AG. 2013. Interplay between manganese and iron in pneumococcal pathogenesis: role of the orphan response regulator RitR. Infect Immun 81:421–429. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00805-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hajaj B, Yesilkaya H, Shafeeq S, Zhi X, Benisty R, Tchalah S, Kuipers OP, Porat N. 2017. CodY regulates thiol peroxidase expression as part of the pneumococcal defense mechanism against H2O2 stress. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:210. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yaakop AS, Chan KG, Ee R, Lim YL, Lee SK, Manan FA, Goh KM. 2016. Characterization of the mechanism of prolonged adaptation to osmotic stress of Jeotgalibacillus malaysiensis via genome and transcriptome sequencing analyses. Sci Rep 6:33660. doi: 10.1038/srep33660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrandiz MJ, de la Campa AG. 2014. The fluoroquinolone levofloxacin triggers the transcriptional activation of iron transport genes that contribute to cell death in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:247–257. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01706-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebhardt MJ, Gallagher LA, Jacobson RK, Usacheva EA, Peterson LR, Zurawski DV, Shuman HA. 2015. Joint transcriptional control of virulence and resistance to antibiotic and environmental stress in Acinetobacter baumannii. mBio 6:e01660-. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01660-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank KL, Colomer-Winter C, Grindle SM, Lemos JA, Schlievert PM, Dunny GM. 2014. Transcriptome analysis of Enterococcus faecalis during mammalian infection shows cells undergo adaptation and exist in a stringent response state. PLoS One 9:e115839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li JS, Bi YT, Dong C, Yang JF, Liang WD. 2011. Transcriptome analysis of adaptive heat shock response of Streptococcus thermophilus. PLoS One 6:e25777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammerschmidt S, Wolff S, Hocke A, Rosseau S, Muller E, Rohde M. 2005. Illustration of pneumococcal polysaccharide capsule during adherence and invasion of epithelial cells. Infect Immun 73:4653–4667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4653-4667.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kietzman CC, Gao G, Mann B, Myers L, Tuomanen EI. 2016. Dynamic capsule restructuring by the main pneumococcal autolysin LytA in response to the epithelium. Nat Commun 7:10859. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Magee AD, Yother J. 2001. Requirement for capsule in colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 69:3755–3761. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3755-3761.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanchez CJ, Kumar N, Lizcano A, Shivshankar P, Dunning Hotopp JC, Jorgensen JH, Tettelin H, Orihuela CJ. 2011. Streptococcus pneumoniae in biofilms are unable to cause invasive disease due to altered virulence determinant production. PLoS One 6:e28738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fasching CE, Grossman T, Corthesy B, Plaut AG, Weiser JN, Janoff EN. 2007. Impact of the molecular form of immunoglobulin A on functional activity in defense against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 75:1801–1810. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01758-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roche AM, Richard AL, Rahkola JT, Janoff EN, Weiser JN. 2015. Antibody blocks acquisition of bacterial colonization through agglutination. Mucosal Immunol 8:176–185. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Habets MN, van Selm S, van der Gaast-de Jongh CE, Diavatopoulos DA, de Jonge MI. 2017. A novel flow cytometry-based assay for the quantification of antibody-dependent pneumococcal agglutination. PLoS One 12:e0170884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitsi E, Roche AM, Reine J, Zangari T, Owugha JT, Pennington SH, Gritzfeld JF, Wright AD, Collins AM, van Selm S, de Jonge MI, Gordon SB, Weiser JN, Ferreira DM. 2017. Agglutination by anti-capsular polysaccharide antibody is associated with protection against experimental human pneumococcal carriage. Mucosal Immunol 10:385–394. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ventura CL, Cartee RT, Forsee WT, Yother J. 2006. Control of capsular polysaccharide chain length by UDP-sugar substrate concentrations in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 61:723–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forsee WT, Cartee RT, Yother J. 2006. Role of the carbohydrate binding site of the Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide type 3 synthase in the transition from oligosaccharide to polysaccharide synthesis. J Biol Chem 281:6283–6289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cartee RT, Forsee WT, Schutzbach JS, Yother J. 2000. Mechanism of type 3 capsular polysaccharide synthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Biol Chem 275:3907–3914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forsee WT, Cartee RT, Yother J. 2009. A kinetic model for chain length modulation of Streptococcus pneumoniae cellubiuronan capsular polysaccharide by nucleotide sugar donor concentrations. J Biol Chem 284:11836–11844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900379200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahdi LK, Van der Hoek MB, Ebrahimie E, Paton JC, Ogunniyi AD. 2015. Characterization of pneumococcal genes involved in bloodstream invasion in a mouse model. PLoS One 10:e0141816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yano M, Pirofski LA. 2011. Characterization of gene use and efficacy of mouse monoclonal antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 8. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:59–66. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00368-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bourgon R, Gentleman R, Huber W. 2010. Independent filtering increases detection power for high-throughput experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9546–9551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914005107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benjamini YHY. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huerta-Cepas J, Forslund K, Pedro Coelho L, Szklarczyk D, Juhl Jensen L, von Mering C, Bork P. 2017. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-mapper. Mol Biol Evol 34:2115–2122. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Price MN, Arkin AP. 2017. PaperBLAST: text mining papers for information about homologs. mSystems 2(4):e00039-17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00039-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu NY, Wagner JR, Laird MR, Melli G, Rey S, Lo R, Dao P, Sahinalp SC, Ester M, Foster LJ, Brinkman FS. 2010. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics 26:1608–1615. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fabrizio K, Groner A, Boes M, Pirofski LA. 2007. A human monoclonal immunoglobulin M reduces bacteremia and inflammation in a mouse model of systemic pneumococcal infection. Clin Vaccine Immunol 14:382–390. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00374-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.