Abstract

Excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (ERCC1), a DNA repair protein, is vital for maintaining genomic fidelity and integrity. Despite the fact that a mounting body of case–control studies has concentrated on investigating the association of the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer risk, there is still no consensus on it. We conducted the current meta-analysis of all eligible articles to reach a much more explicit conclusion on this ambiguous association. A total of seven studies involving 2354 breast cancer cases and 2193 controls were elaborately selected for this analysis from the Embase, EBSCO, PubMed, WanFang, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated in our meta-analysis. We found that the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism was significantly associated with breast cancer risk under all genetic models. When excluded, the studies that deviated from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), the pooled results of what remained significantly increase the risk of breast cancer under the allele model (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.02–1.27, P=0.02), heterozygote model (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.06–1.44, P=0.007), and dominant model (OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.05–1.41, P=0.01). This increased breast cancer risk was found in Asian population as well as under the heterozygote model (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.05–1.48, P=0.013) and dominant model (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.02–1.42, P=0.03). Our results suggest that the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism is associated with breast cancer susceptibility, and in particular, this increased risk of breast cancer existence in Asian population.

Keywords: Breast cancer, ERCC1, Meta-analysis, Polymorphism, Susceptibility

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignancies in females and it alone accounts for 25% of all the cancer cases as well as 15% of cancer deaths amongst females [1,2]. Although early detection through mammography and improved treatment have contributed to the decrease in breast cancer death rate in Europe [3,4], we are still confronted with a high incidence of new breast cancer diagnoses, causing it to be a major public health problem. Numerous studies have shown that the genetic, endocrine, and external environments contribute to the occurrence and development of breast cancer [5,6]; however, the specific mechanisms amongst these multiple factors are still a mystery. Genomic instability is a potential carcinogenic factor; organisms have developed an elaborated set of DNA repair systems involving multiple sophisticated mechanisms for repairing an extremely broad array of DNA lesions induced by internal and external stressors to maintain genome integrity and stability [7,8]. A series of proteins assemble and respond to DNA damage in a stepwise fashion in these pathways, and the alteration of genes encoding such proteins undoubtedly contributes to the variability of the more directly implicated genes and may therefore be significantly related to the risk of cancer [9].

Excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (ERCC1) is a critical DNA repair protein and is involved in several distinct DNA-damage repair pathways, including nucleotide excision repair (NER), base excision repair (BER), interstrand cross-link (ICL) repair, and recombinational DNA repair [10–13], in the form of a highly conserved heterodimeric complex that combines with the xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group F (XPF) endonuclease. The structure-specific endonuclease ERCC1-XPF serves as an indispensable component in a given DNA repair pathway by catalyzing the incision of the 5′-phosphodiester backbone around the site of DNA lesions caused by a variety of environmental carcinogens and chemotherapeutic agents [14,15]. Previous research revealed that ERCC1 gene polymorphisms were associated with reduced mRNA and protein expression levels in various types of carcinomatosis [16–18]. The immediate impairment in DNA repair capacity on account of genetic variation may contribute to interindividual variability in cancer susceptibility.

A number of epidemiological studies and meta-analyses of the association between ERCC1 gene polymorphisms and the risks of several types of cancer such as lung cancer, adult glioma, colorectal cancers, bladder cancer, and head and neck carcinomas have been reported [19–24]. In addition, a pooled result showed that within Caucasian population, individuals with the ERCC1 rs3212986 gene polymorphism suffer a higher risk of breast cancer [25]. Several case–control studies focussed on the ERCC1 rs11615 gene polymorphism and breast cancer risk have produced mutually contradictory results [26–32]. Thus, we performed this meta-analysis based on the available case–control studies to expound the effect of the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism on breast cancer risk.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We searched for relevant articles published in the Embase, EBSCO, PubMed, WanFang, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases up to December 2017, using the following terms: ‘breast carcinoma’ or ‘breast cancer’ or ‘breast neoplasm’ AND ‘polymorphism’ or ‘genetic variant’ or ‘single-nucleotide polymorphism’ (‘SNP’) AND ‘ERCC1’ or ‘354 T>C’ or ‘G19007A’ or ‘rs11615’. All the relevant studies were retrieved for screening of the abstracts, full-text reports, and references by two investigators independently. Authors were contacted to obtain relevant data not present in the original articles. There was no language restriction on the search and selection of the articles.

Selection criteria

An article was included in our meta-analysis if it met the following selection criteria: (i) the study evaluated the association between the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer risk; (ii) the study was an independent case–control study for humans; and (iii) genotype frequencies of case and control groups were stated in the article or could be obtained by contacting the authors. We excluded reviews, conference papers, and other studies that were published in abstracts only. When publications had obvious overlapping data in terms of the study participants, we kept only the study with the largest sample size.

Data extraction

A standardized form was used for information collection from each retrieved study by two investigators independently. We collected information on the first author’s name, year of publication, ethnicity (Caucasian, Asian, and others), country, total number of cases and controls, genotyping method, the distribution of genotypes in cases and control subjects, evidence of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control group, and association with breast cancer. During the data extraction, there was an open discussion amongst all the investigators for reaching a final consensus regarding discrepancies.

Statistical analysis

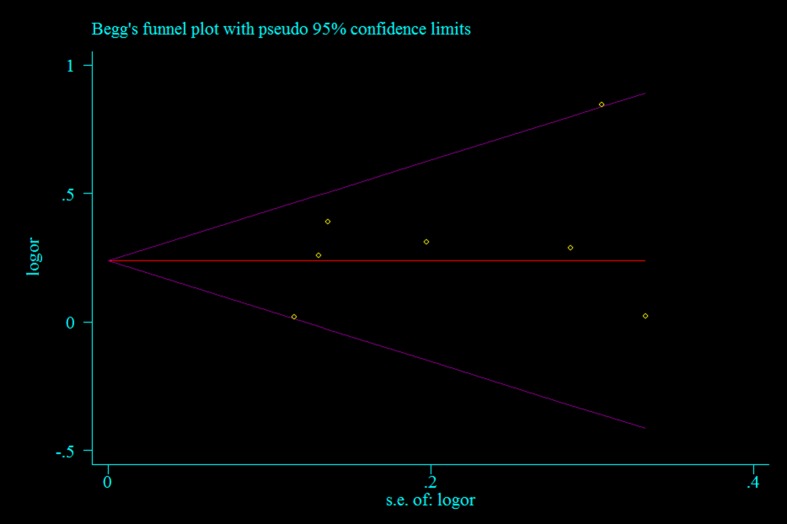

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to estimate the association between the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer risk in the allele model (T compared with C), homozygous model (TT compared with CC), heterozygous model (TC compared with CC), recessive model (TT compared with TC + CC), and dominant model (TC + TT compared with CC); P<0.05 was considered significant. We assessed HWE in control subjects of each study by the χ2 test (https://ihg.gsf.de/cgi-bin/hw/hwa2.pl; accessed 10 January 2018) [28] and evaluated whether the results were different after excluding studies that had statistically significant (P<0.05) violation of HWE [33]. The statistical heterogeneity amongst studies was evaluated with the Q statistic based on a standard Chi-square test with a P<0.10 [34] and I2 values that manifested the definite extent of between-study heterogeneity [35]. A random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled ORs and 95% CI if the P-value of heterogeneity tests was no more than 0.10 [36]; otherwise, a fixed-effect model was selected [37]. Further, we conducted subgroup tests stratified by ethnicity as well as genotyping method when more than one study was included. Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding one study at a time and then calculating the pooled ORs by repeating the meta-analysis to assess the stability of the results. We used Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test to evaluate publication bias, with P<0.05 being considered significant publication bias [38].

Results

Characteristics of included studies

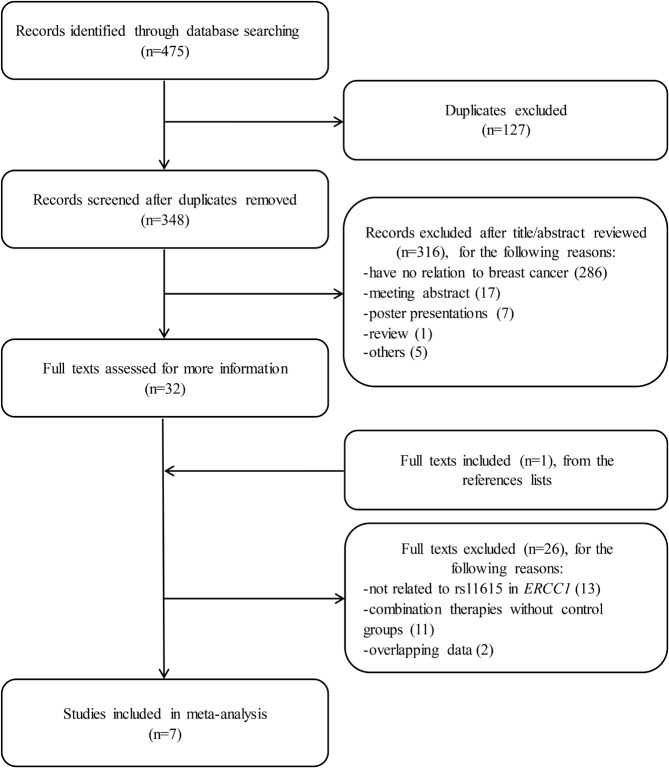

A total of 475 publications were preliminarily identified after systematically searching the aforementioned databases based on our search strategy using different search term combinations. All articles were scrutinized carefully by reading the full texts, and the studies that conformed to the selection criteria stringently as mentioned above were selected for this meta-analysis. The detailed selection process is shown in Figure 1. In the end, seven case–control studies about the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer risk were included in our study, encompassing 2354 cases and 2193 controls.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of article selection for our meta-analysis.

The characteristics of the eligible studies are shown in Table 1. The seven case–control papers were published between 2003 and 2017, and one study was performed in a Caucasian population, one in Mexican mixed population, and five in Asian population. All control subjects in these studies were within HWE, except for those conducted by Yang et al. [28] and Pongsavee et al. [32]. It came as a little surprise that there were two studies stratified by menopausal status (premenopausal and postmenopausal) with specific genotype data [27,31], and one committed to investigating postmenopausal breast cancer [26]. The information of premenopausal and postmenopausal subsets was also collected as we mentioned earlier (data not shown).

Table 1. Main characteristics of eligible studies in this meta-analysis.

| Author names | Years | Areas | Ethnicity | Genotyping method | Cases/controls | Cases | Controls | HWE | Association observed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CT | TT | CC | CT | TT | ||||||||

| Nexo et al. [26] | 2003 | Denmark | Caucasian | TaqMan | 415/414 | 53 | 176 | 186 | 69 | 183 | 162 | YES | No risk |

| Lee et al. [27] | 2005 | Korea | Asian | MALDI-TOF | 705/550 | 411 | 257 | 37 | 323 | 187 | 40 | YES | No risk |

| Yang et al. [28] | 2013 | China | Asian | TaqMan | 461/504 | 183 | 166 | 112 | 232 | 184 | 88 | NO | TT genotype showed increased risk |

| Zhu et al. [29] | 2015 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | 101/101 | 56 | 41 | 4 | 63 | 33 | 5 | YES | No risk |

| Gomez-Diaz et al. [30] | 2015 | Mexico | Mexican-mestizo | TaqMan | 71/74 | 38 | 28 | 5 | 40 | 27 | 7 | YES | No risk |

| He et al. [31] | 2016 | China | Asian | MALDI-TOF | 450/430 | 230 | 195 | 25 | 261 | 151 | 18 | YES | TT/TC genotype showed increased risk |

| Pongsavee et al. [32] | 2017 | Thailand | Asian | TaqMan | 151/120 | 105 | 33 | 13 | 101 | 9 | 10 | NO | TT/TC genotype showed increased risk |

Abbreviation: PCR-RFLP, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Meta-analysis results

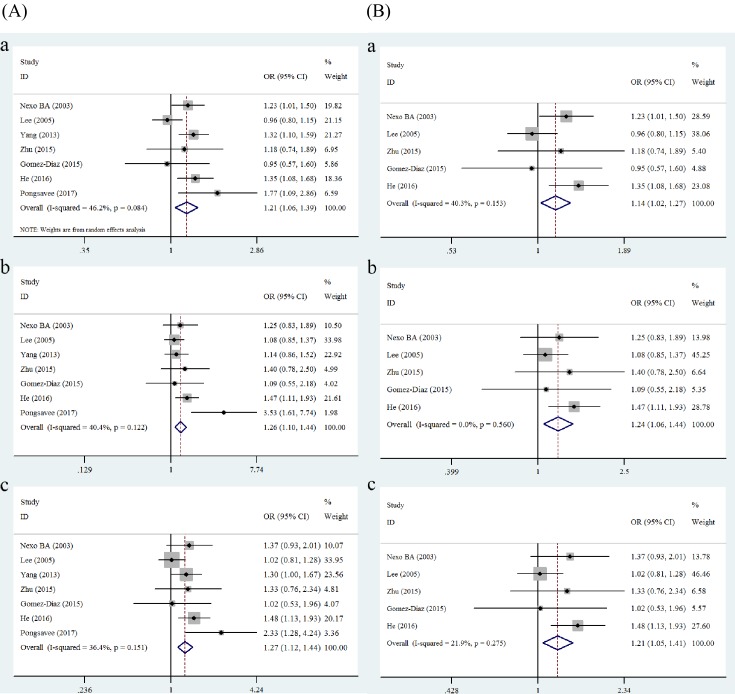

The pooled results indicated that there is a statistically significant relationship between the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and increased breast cancer risk in all genetic models: the allele model (OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.06–1.39, P=0.006), homozygous model (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.06–1.59, P=0.013), heterozygote model (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.10–1.44, P=0.001), recessive model (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.01–1.43, P=0.036), and dominant model (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.12–1.44, P<0.001) (Table 2 and Figure 2). The next pooled analysis, which excluded studies that were not consistent with HWE, also suggested that ERCC1 rs11615 was a breast cancer risk factor under the allele model (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.02–1.27, P=0.02), heterozygote model (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.06–1.44, P=0.007) and dominant model (OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.05–1.41, P=0.01) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2. Meta-analysis results of the association between the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility.

| Groups | Cases/controls | Genetic model | Test of association | Test of heterogeneity | Effects model | Begg’s test | Egger’s test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | I2(%) | Pheterogeneity | P | P | ||||

| Overall | 2354/2193 | T compared with C | 1.21 | 1.06–1.39 | 0.006 | 46.2 | 0.08 | R | 1.00 | 0.72 |

| TT compared with CC | 1.29 | 1.06–1.59 | 0.013 | 35.2 | 0.16 | F | 0.13 | 0.38 | ||

| TC compared with CC | 1.26 | 1.10–1.44 | 0.001 | 40.4 | 0.12 | F | 0.23 | 0.20 | ||

| TT compared with TC/CC | 1.20 | 1.01–1.43 | 0.036 | 30.6 | 0.20 | F | 0.23 | 0.25 | ||

| TC/TT compared with CC | 1.27 | 1.12–1.44 | P<0.001 | 36.4 | 0.15 | F | 0.76 | 0.35 | ||

| Asians | 1868/1705 | T compared with C | 1.24 | 1.03–1.50 | 0.025 | 61.3 | 0.04 | R | 0.81 | 0.49 |

| TT compared with CC | 1.21 | 0.82–1.78 | 0.34 | 50.0 | 0.09 | R | 0.46 | 0.66 | ||

| TC compared with CC | 1.35 | 1.05–1.74 | 0.021 | 59.6 | 0.04 | R | 0.22 | 0.13 | ||

| TT compared with TC/CC | 1.10 | 0.76–1.60 | 0.60 | 48.8 | 0.10 | R | 0.46 | 0.47 | ||

| TC/TT compared with CC | 1.33 | 1.07–1.66 | 0.011 | 54.9 | 0.06 | R | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||

| HWE (P>0.05)* | ||||||||||

| Overall | 1742/1569 | T compared with C | 1.14 | 1.02–1.27 | 0.02 | 40.3 | 0.15 | F | 1.00 | 0.98 |

| TT compared with CC | 1.14 | 0.87–1.48 | 0.34 | 40.5 | 0.15 | F | 0.81 | 0.71 | ||

| TC compared with CC | 1.24 | 1.06–1.44 | 0.007 | 0 | 0.56 | F | 1.00 | 0.82 | ||

| TT compared with TC/CC | 1.09 | 0.88–1.35 | 0.43 | 28.6 | 0.23 | F | 0.81 | 0.43 | ||

| TC/TT compared with CC | 1.21 | 1.05–1.41 | 0.01 | 21.9 | 0.28 | F | 0.81 | 0.78 | ||

| Asians | 1256/1081 | T compared with C | 1.14 | 0.88–1.46 | 0.32 | 63.9 | 0.06 | R | 1.00 | 0.79 |

| TT compared with CC | 0.96 | 0.67–1.37 | 0.81 | 46.2 | 0.16 | F | 1.00 | 0.82 | ||

| TC compared with CC | 1.24 | 1.05–1.48 | 0.013 | 29.9 | 0.24 | F | 1.00 | 0.72 | ||

| TT compared with TC/CC | 0.88 | 0.62–1.26 | 0.50 | 25.9 | 0.26 | F | 1.00 | 0.85 | ||

| TC/TT compared with CC | 1.20 | 1.0–1.42 | 0.03 | 55.4 | 0.11 | F | 1.00 | 0.75 | ||

Abbreviations: F, fixed-effects model; P value, P-value for association; Pheterogeneity, P-value for heterogeneity; R, random-effects model. P-values <0.05 are indicated in bold.

The studies that clearly deviated from HWE were excluded.

Figure 2. Forest plots of breast cancer risk associated with ERCC1 rs11615.

The plots were grouped into (A) and (B) for comparison. (A) All studies: (a) allele model (T compared with C); (b) heterozygous model (TC compared with CC); (c) dominant model (TC + TT compared with CC). (B) After excluding the studies that deviated from HWE: (a) allele model (T compared with C); (b) heterozygous model (TC compared with CC); (c) dominant model (TC + TT compared with CC).

Subgroup analysis results

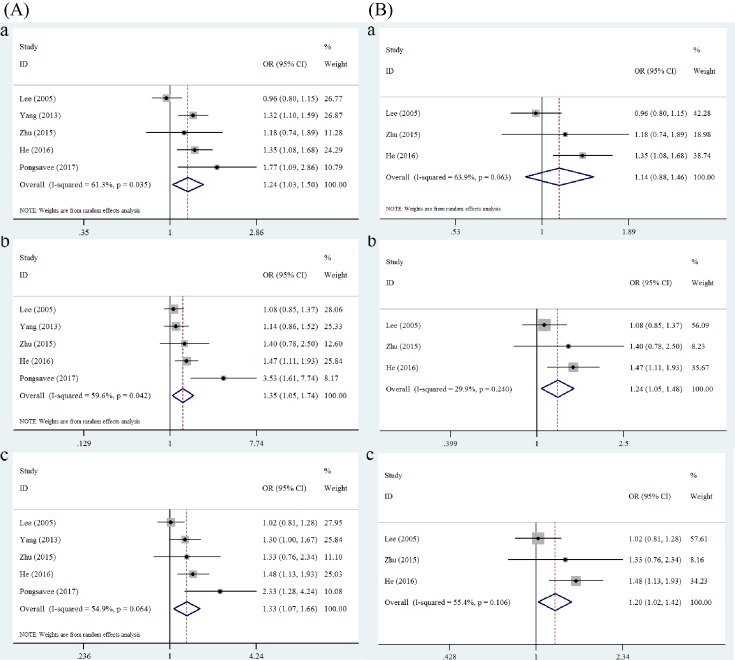

Five case–control studies were included for subgroup analysis of Asian (China, Korea, Thailand) populations, while no subgroup analysis of the Caucasian population and Mexican-mestizo population was conducted, for each of which there was only study amongst the eligible studies. The stratified analysis showed an increased breast cancer risk in Asian populations based on the allele model (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.03–1.50, P=0.025), heterozygote model (OR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.05–1.74, P=0.021), and dominant model (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.07–1.66, P=0.011) (Table 2 and Figure 3). We also found that there were two studies that deviated from HWE in this subset; further pooled results after excluding them indicated that the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism still increased the breast cancer risk under the heterozygote model (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.05–1.48, P=0.013) and dominant model (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.02–1.42, P=0.03) (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plots of breast cancer risk associated with ERCC1 rs11615 in Asian populations.

The plots were grouped into (A) and (B) for comparison. (A) All studies: (a) allele model (T compared with C); (b) heterozygous model (TC compared with CC); (c) dominant model (TC + TT compared with CC). (B) After excluding the studies that deviated from HWE: (a) allele model (T compared with C); (b) heterozygous model (TC compared with CC); (c) dominant model (TC + TT compared with CC).

Subgroup analysis of different genotyping methods (Taqman, MALDI-TOF, no PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) for only one study) showed no relationship between ERCC1 rs11615 and breast cancer risk, when including the studies that were deviant from HWE or not. In addition, when the data were stratified by menopausal status, there was no significant difference in the risk of breast cancer.

Sensitivity analysis

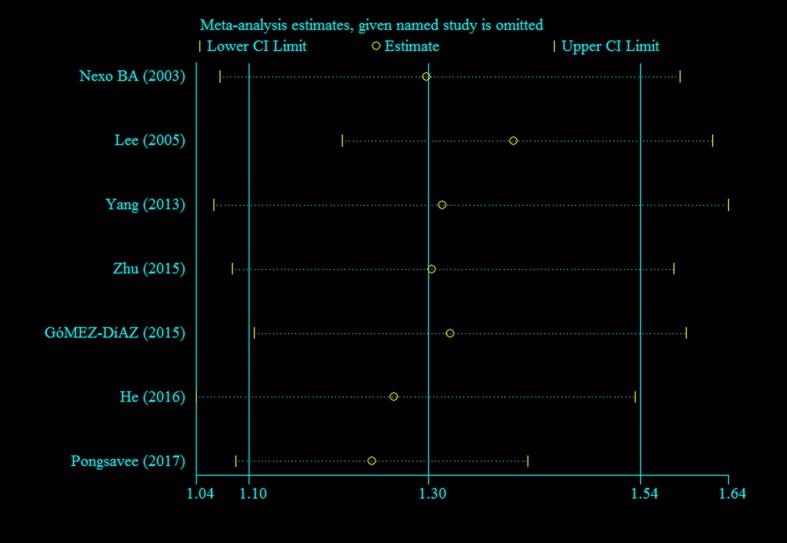

To observe the impact of each single study on the pooled OR, sensitivity analysis was performed by removing each study sequentially. In each case, the overall outcomes for the different genetic models showed no statistically significant changes, suggesting that this meta-analysis has good stability and reliability (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Sensitivity analysis of the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer risk (dominant model: TC + TT compared with CC).

Detection of heterogeneity and publication bias

Heterogeneity amongst the studies was evaluated using the Q-test and I2 statistics. Substantial heterogeneity (P<0.10) was found, whereas no I2values were more than 75%. Thus, a model was applied to synthesize the data (Table 2). We use Begg’s funnel plot and the Egger’s test to evaluate publication bias. The funnel plot is symmetrical, indicating that there is no significant publication bias in the total population (Table 2 and Figure 5).

Figure 5. Funnel plot for evaluating publication bias in the seven studies (dominant model: TC + TT compared with CC).

Discussion

DNA repair systems play a vital role in maintaining the integrity and fidelity of the genome, and DNA repair capacity is a potentially important source of interindividual variability in relation to the development of cancer [39]. Particularly, polymorphisms in DNA repair genes can affect DNA repair capacity. Much attention has been drawn to heritable polymorphisms in DNA repair genes in relation to breast cancer risk; amongst such genes, ERCC1 is highly polymorphic. Previous case–control studies focussed largely on the associations between breast cancer risk and two common variants, rs11615 and rs3212986. Although six prior studies have investigated the correlation between the ERCC1 rs3212986 polymorphism and breast cancer development, no definite conclusions have been reached regarding this causal relationship [27,28,40–43]. The recent meta-analysis from Guo et al. [25] showed that amongst Caucasian populations, individuals with the rs3212986 polymorphism in the ERCC1 gene have a higher risk of breast cancer. In the present meta-analysis, we paid special attention to the role of the rs11615 polymorphism in breast cancer risk. To date, there have been seven case–control studies devoted to shedding light on the link between the rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer risk. The studies conducted by Yang et al. [28], He et al. [31], and Pongsavee et al. [32] found that the rs11615 polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, while others drew the opposite conclusion [26,27,29,30]. Here, we looked for powerful evidence that either supports or refutes the validity of associations between the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism and breast cancer risk.

Our pooled study demonstrated a clear increase in breast cancer risk associated with the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism under all genetic models (all P<0.05). We found no evidence of publication bias, and the results showed no instability through sensitivity analysis, convincing us of the reliability of the current meta-analysis. However, we took notice of deviations from HWE in the studies we included by Yang et al. [28] and Pongsavee et al. [32]. Genotyping errors, population stratification, and other genetic factors such as inbreeding or deletions can induce departure from HWE [44,45], which may, in some instances lead to false conclusions. To clarify if our meta-analysis results were altered by the studies by Yang et al. [28] and Pongsavee et al. [32], we ran an analysis again after excluding the data extracted from them. The increased risk of breast cancer under the allele model, heterozygous model and dominant model was still nominally significant (P=0.02, P=0.007, and P=0.01, respectively), which further confirmed the significant role played by ERCC1 rs11615 in breast cancer susceptibility. The obvious alteration of P-values and estimates of effect size previously ascertained in all the genetic models could be due to reduced sample size, given that the two excluded studies accounted for 27.18% of individuals [46].

In further subgroup analysis by ethnicity, the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in Asian populations. Unfortunately, there are no ample studies of Mexican-mestizo and Caucasian populations included in this meta-analysis. As a consequence, it is still too early to tell the role that the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism plays in breast cancer risk variation in different ethnic backgrounds. Extremely large-scale single studies of different ethnicities are now necessary to draw a more precise conclusion about the specific significant association suggested by our intriguing finding. In addition, breast cancer is heterogeneous; De Waard et al. [47,48] showed a bimodal type of age distribution of breast cancer, which was considered to be related to menopause, and put forward the existence of two types of human breast cancer. In this meta-analysis, we tried to explore the role of the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism in premenopausal and postmenopausal females. However, we did not find any difference between premenopausal and postmenopausal females in breast cancer susceptibility associated with ERCC1 rs11615, contrary to the results by Lee et al. [27] and He et al. [31]. To date, the risk of breast cancer conferred by the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism in relation to menopausal status has not been widely and thoroughly investigated and may be a promising area for breast cancer research.

Some limitations in the present meta-analysis should be noted. First, having only a total of seven papers, and even fewer after grouping, may limit the statistical power and result in some genuine associations being undetected. As previously described, it is unreasonable to state that there is a definite racial difference in the contribution of the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism to breast cancer risk due to the insufficient number of studies. Second, the existence of heterogeneity in some models may generate false positive signals, while it could also lead to false negatives for some potential associations. We failed to discover any notable source of heterogeneity when we executed meta-regression analysis based on year, ethnicity, genotyping methods, and HWE in the control group (data not shown). Finally, compared with individual SNP loci, haplotypes may increase associations with disease. A study by Nexo et al. [26] found that by combining SNPs in the chromosomal region 19q13.2–3, they could detect a significantly increased risk of postmenopausal breast cancer, while none of the single SNPs showed this association [24]. The SNPs rs11615 and rs3212961 in ERCC1 have strong or moderate linkage disequilibrium in Asian and European populations [49] and may be a significant haplotype. Our pooled results provide strong evidence of the increased risk of breast cancer for ERCC1 rs11615, and Romanowicz et al. [9] concluded that Caucasian populations with the CC genotype of ERCC1 rs3212961 have 10.61-times the risk of developing breast cancer. Thus, certain haplotypes may increase the strength of an individual polymorphism and lead to significant enrichment of essential biological functions. Unfortunately, no article in the present meta-analysis analyzed the frequency distributions of haplotypes except the one by Nexo et al. [26]. Further association analyses of ERCC1 haplotypes are imperative.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis does demonstrate that the ERCC1 rs11615 polymorphism significantly increases the risk of breast cancer. This significant association is observed in Asian populations, but more studies are necessary to determine if there is such an association in other races. Taking all our findings together, the increased risk of breast cancer under the heterozygote model and dominant model persisted, revealing that the TC genotype plays a crucial role in determining breast cancer risk. Well-designed case–control studies with larger sample sizes and examining populations from across the world are essential for the exploration of the association between breast cancer risk and ERCC1 gene polymorphisms, other DNA repair gene polymorphisms, and even the relevant haplotypes.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- ERCC1

excision repair cross-complementation group 1

- HWE

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- OR

odds ratio

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- XPF

xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group F

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province [grant number 172102310077].

Author contribution

D.Q. and B.L. conceived and designed the study and finally approved the manuscript. B.L., X.S., and Y.Y. searched the literature, collected and managed data, made the statistical analysis, and interpreted the result. M.P. and H.F. participated in discussions, checked data validity, and integrity and corrected the draft. All authors wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Torre L.A., Bray F., Siegel R.L., Ferlay J., Lortet-Tieulent J. and Jemal A. (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 87–108 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma S.J., Liu Y.M., Zhang Y.L., Chen M.W. and Cao W. (2018) Correlations of EZH2 and SMYD3 gene polymorphisms with breast cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Biosci. Rep. 38, 10.1042/BSR20170656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosetti C., Bertuccio P., Levi F., Chatenoud L., Negri E. and La Vecchia C. (2012) The decline in breast cancer mortality in Europe: an update (to 2009). Breast 21, 77–82 10.1016/j.breast.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Autier P., Boniol M., Gavin A. and Vatten L.J. (2011) Breast cancer mortality in neighbouring European countries with different levels of screening but similar access to treatment: trend analysis of WHO mortality database. BMJ 343, d4411 10.1136/bmj.d4411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavalieri E.L. and Rogan E.G. (2012) The etiology and prevention of breast cancer. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Mech. 9, e55–e69 , 10.1016/j.ddmec.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao Z., Shi A., Lu C., Song T., Zhang Z. and Zhao J. (2015) Breast cancer: epidemiology and etiology. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 72, 333–338 10.1007/s12013-014-0459-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakem R. (2008) DNA-damage repair; the good, the bad, and the ugly. EMBO. J. 27, 589–605 10.1038/emboj.2008.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furgason J.M. and Bahassi E.M. (2013) Targeting DNA repair mechanisms in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 137, 298–308 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romanowicz H., Pyziak L., Jablonski F., Brys M., Forma E. and Smolarz B. (2017) Analysis of DNA repair genes polymorphisms in breast cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 23, 117–123 10.1007/s12253-016-0110-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scharer O.D. (2017) ERCC1-XPF endonuclease-positioned to cut. EMBO J. 36, 1993–1995 10.15252/embj.201797489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodrick J., Gupta S., Camacho S., Parvathaneni S., Choudhury S., Cheema A. et al. (2017) A new sub-pathway of long-patch base excision repair involving 5′ gap formation. EMBO. J. 36, 1605–1622, 10.15252/embj.201694920 10.15252/embj.201694920 28373211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douwel D.K., Hoogenboom W.S., Boonen R.A.C.M. and Knipscheer P. (2017) Recruitment and positioning determine the specific role of the XPF-ERCC1 endonuclease in interstrand crosslink repair. EMBO. J. 36, 2034–2046 10.15252/embj.201695223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang N., Liu X., Li L. and Legerski R. (2007) Double-strand breaks induce homologous recombinational repair of interstrand cross-links via cooperation of MSH2, ERCC1-XPF, REV3, and the Fanconi anemia pathway. DNA Rep. (Amst.) 6, 1670–1678 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araujo S.J. and Wood R.D. (1999) Protein complexes in nucleotide excision repair. Mutat. Res. 435, 23–33 10.1016/S0921-8777(99)00042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagbemi A.F., Orelli B. and Scharer O.D. (2011) Regulation of endonuclease activity in human nucleotide excision repair. DNA Rep. (Amst.) 10, 722–729 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woelfelschneider A., Popanda O., Lilla C., Linseisen J., Mayer C., Celebi O. et al. (2008) A distinct ERCC1 haplotype is associated with mRNA expression levels in prostate cancer patients. Carcinogenesis 29, 1758–1764 10.1093/carcin/bgn067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goode E.L., Ulrich C.M. and Potter J.D. (2002) Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes and associations with cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 11, 1513–1530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu J.J., Mu C., Lee K.B., Okamoto A., Reed E.L., Bostick-Bruton F. et al. (1997) A nucleotide polymorphism in ERCC1 in human ovarian cancer cell lines and tumor tissues. Mutat. Res. 382, 13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du L.H., Yu W., Dai X.K., Zhao N.N., Huang X., Tong F. et al. (2018) Association of DNA repair gene polymorphisms with the risk of radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer patients. Oncotarget 9, 958–968 10.18632/oncotarget.22982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie F., Sun Q., Wu S., Xie X. and Liu Z. (2014) Nucleotide excision repair gene ERCC1 19007T >C polymorphism contributes to lung cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 18, 591–595 10.1089/gtmb.2013.0329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yueh T.C., Chou A.K., Gong C.L., Fu C.K., Pei J.S., Wu M.H. et al. (2017) The contribution of excision repair cross-complementing group 1 genotypes to colorectal cancer susceptibility in Taiwan. Anticancer Res. 37, 2307–2313 10.21873/anticanres.11568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J.F., Sun N.J., Hu G., Chen X.S., Jiang J.S., Wu H.M. et al. (2017) Association of ERCC1 polymorphisms with the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 27, 267–275 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2017019713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geng P.L., Ou J.J., Li J.J., Liao Y.M., Wang N., Xie G.F. et al. (2016) A comprehensive analysis of influence ERCC polymorphisms confer on the development of brain tumors. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 2705–2714 10.1007/s12035-015-9371-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding Y.W., Gao X., Ye D.X., Liu W., Wu L. and Sun H.Y. (2015) Association of ERCC1 polymorphisms (rs3212986 and rs11615) with the risk of head and neck carcinomas based on case-control studies. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 17, 710–719 10.1007/s12094-015-1298-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo X.-G., Wang Q., Xia Y. and Zheng L. (2015) The C8092A polymorphism in the ERCC1 gene and breast carcinoma risk: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 3691–3699 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nexo B.A., Vogel U., Olsen A., Ketelsen T., Bukowy Z., Thomsen B.L. et al. (2003) A specific haplotype of single nucleotide polymorphisms on chromosome 19q13.2-3 encompassing the gene RAI is indicative of post-menopausal breast cancer before age 55. Carcinogenesis 24, 899–904 10.1093/carcin/bgg043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee K.M., Choi J.Y., Kang C.W., Kang C.P., Park S.K., Cho H.M. et al. (2005) Genetic polymorphisms of selected DNA repair genes, estrogen and progesterone receptor status, and breast cancer risk. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 4620–4626 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Z., Fang X., Pei X. and Li H. (2013) Polymorphisms in the ERCC1 and XPF genes and risk of breast cancer in a Chinese population. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 17, 700–706 10.1089/gtmb.2013.0122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu G., Wang L., Guo H., Lu L., Yang S., Wang T. et al. (2015) DNA repair genes XRCC1 and ERCC1 polymorphisms and the risk of sporadic breast cancer in han women in the gansu province of China. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 19, 387–393 10.1089/gtmb.2015.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomez-Diaz B., DE LA Luz Ayala-Madrigal M, Gutierrez-Angulo M., Valle-Solis A.E., Linares-Gonzalez L.M., Gonzalez-Guzman R. et al. (2015) Analysis of ERCC1 and ERCC2 gene variants in osteosarcoma, colorectal and breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 9, 1657–1661 10.3892/ol.2015.2894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He B.-s., Xu T., Pan Y.-q., Wang H.-j., Cho W.C., Lin K. et al. (2016) Nucleotide excision repair pathway gene polymorphisms are linked to breast cancer risk in a Chinese population. Oncotarget 7, 84872–84882 10.18632/oncotarget.12744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pongsavee M., Wisuwan K. and Tiwawech D. (2017) Association between ERCC1 polymorphism and the risk and clinicopathological features of breast cancer in thai women in the lower northeastern region. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 18, 2999–3002, 10.22034/apjcp.2017.18.11.2999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vineis P., Manuguerra M., Kavvoura F.K., Guarrera S., Allione A., Rosa F. et al. (2009) A field synopsis on low-penetrance variants in DNA repair genes and cancer susceptibility. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 101, 24–36 10.1093/jnci/djn437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J. and Altman D.G. (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins J.P.T. and Thompson S.G. (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21, 1539–1558 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi X., Jin H., Peng M., Li B., She M., Zhu T. et al. (2018) Association between NME1 polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis based on 1644 cases and 2038 controls. Pathol. Res. Pract. 10.1016/j.prp.2018.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng M., Zhou X., Ding X., Wei L., Zhao Y., Zhu T. et al. (2017) Association of XRCC1 Arg399Gln and Arg194Trp polymorphisms with susceptibility to multiple autoimmune diseases: a meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 37, 435–444 10.1007/s00296-016-3585-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J., Gao S., Xu J. and Zhu J. (2018) Prognostic value and clinicopathological significance of serum- and tissue-based cytokeratin 18 express level in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 10.1042/BSR20171145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berwick M. and Vineis P. (2000) Markers of DNA repair and susceptibility to cancer in humans: an epidemiologic review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 874–897 10.1093/jnci/92.11.874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen J., Desai M., Agrawal M., Kennedy D.O., Senie R.T., Santella R.M. et al. (2006) Polymorphisms in nucleotide excision repair genes and DNA repair capacity phenotype in sisters discordant for breast cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research. Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 15, 1614–1619, 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crew K., Gammon M., Terry M., Zhang F., Zablotska L., Agrawal M. et al. (2007) Polymorphisms in nucleotide excision repair genes, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts, and breast cancer risk, Cancer Epidemiol. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16, 2033–2041 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pei X., Yang Z., Lv X. and Li H. (2014) Genetic variation in ERCC1 and XPF genes and breast cancer risk. Genet. Mol. Res. 13, 2259–2267 10.4238/2014.March.31.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao R. and Ying M.F. (2016) Association between ERCC1 and ERCC2 polymorphisms and breast cancer risk in a Chinese population. Genet. Mol. Res. 15, 15017263 10.4238/gmr.15017263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leal S.M. (2005) Detection of genotyping errors and pseudo-SNPs via deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Genet. Epidemiol. 29, 204–214 10.1002/gepi.20086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hosking L., Lumsden S., Lewis K., Yeo A., McCarthy L., Bansal A. et al. (2004) Detection of genotyping errors by Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 12, 395–399 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Czamara D., Müller-Myhsok B. and Lucae S. (2018) The P2RX7 polymorphism rs2230912 is associated with depression: a meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 272–277 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Waard F., De Laive J. and Baanders-Vanhalewijn E.A. (1960) On the bimodal age distribution of mammary carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 14, 437–448 10.1038/bjc.1960.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Waard F., Baanders-Vanhalewijn E.A. and Huizinga J. (1964) The bimodal age distribution of patients with mammary carcinoma; evidence for the existence of 2 types of human breast cancer. Cancer 17, 141–151 10.1002/1097-0142(196402)17:2%3c141::AID-CNCR2820170202%3e3.0.CO;2-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L., Wang J., Xu L., Zhou J., Guan X., Jiang F. et al. (2012) Nucleotide excision repair gene ERCC1 polymorphisms contribute to cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Mutagenesis 27, 67–76 10.1093/mutage/ger062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]