Abstract

Background

The advent of mobile technology has ushered in an era in which smartphone apps can be used as interventions for suicidality.

Objective

We aimed to review recent research that is relevant to smartphone apps that can be used for mindfulness interventions for suicidality in Asian youths.

Methods

The inclusion criteria for this review were: papers published in peer-reviewed journals from 2007 to 2017 with usage of search terms (namely “smartphone application” and “mindfulness”) and screened by an experienced Asian clinician to be of clinical utility for mindfulness interventions for suicidality with Asian youths.

Results

The initial search of databases yielded 375 results. Fourteen full text papers that fit the inclusion criteria were assessed for eligibility and 10 papers were included in the current review.

Conclusions

This review highlighted the paucity of evidence-based and empirically validated research into effective smartphone apps that can be used for mindfulness interventions for suicidality with Asian youths.

Keywords: suicidality, Asian youths, smartphone applications, mindfulness

Introduction

Suicide rates increase with age from adolescence to young adulthood [1,2], with corresponding heightened rates of suicidal ideation and attempts [3]. Both Western and Asian studies have highlighted the prevalence of youth suicidality, and youth suicide rates have been rising faster compared to other age groups [4,5], with a peak in those between 15 and 24 years of age [3,6,7]. In a recent large study on Asian suicide attempters in Singapore, a prominent peak in suicide attempts over a 3-year period was observed in youths aged between 15-24 years, as compared to other age groups [4].

In recent decades, the advent of smartphone technologies has transformed the mode of delivery of psychological treatment [8] for patients suffering from chronic medical illnesses [9,10] and psychiatric illnesses [11], as well as their caregivers [12]. The demand for electronic health apps across the world is mirroring larger societal trends wherein consumer acceptance of technology has grown [13,14].

Common psychiatric illness such as depression are associated with high direct and indirect costs [15]. Psychiatric illnesses result in functional impairment, leading to lost wages and work impairment, with related personal, societal, and economic burdens [16,17]. Smartphone apps have the potential to reduce health care costs for treating psychiatric illnesses in Asia [18,19]. In comparison to Western countries, there is a shortage of mental health professionals in Asia, yet a high penetration of mobile phone usage throughout Asia [20]. Over 50% of the Asian population uses smartphones, with Singapore alone reporting that smartphone adoption rates far exceeded the population [21]. There is a critical need for comprehensive research to inform the development of evidence-based smartphone apps that can be made widely available for the public, to ameliorate symptoms and improve well-being in Asian populations.

As younger demographics are more likely to access online information related to mental health problems [22-24], mobile technologies can enhance patient-centered care for youths in an increasingly technology savvy society [25], highlighting a growing need to offer electronic interventions [26,27]. The evidence base for the use of smartphone apps has been demonstrated in many areas [28-33], and Internet-based interventions have been found to be efficacious for mental health issues [34] in young adults [23,26,35] to enhance support [36], help them to cope, and to aid in recovery [37,38]. Positive outcomes were shown in overall motivation [39] and with ethnically diverse populations [40]. Smartphone apps have been used to deliver therapies that are relevant to young adults, such as cognitive behavior therapy [10], addiction treatment [41], and virtual reality therapy [42]. These findings hold promise for mental health professionals who are not technical experts to develop smartphone apps as an alternative platform to deliver interventions, in view of the recent advances in technology [43]. However, it should not be assumed that smartphone apps delivering interventions demonstrated to be effective in Western cultures will be similarly effective in Asian cultures [44]. Cultural adaptations may be needed for Asian youths [45].

Some clinics in Australia have implemented conjunctive treatment modalities in guided programs such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and psychoeducation apps alongside face-to-face therapy sessions [40]. One example is the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Coach, which was an app that was designed after extensive feedback from experts [46]. The app aimed at cultivating emotional regulation skills to change negative emotions [47]. The users gave ratings and identified the current emotion, after which users were directed to specific coaching [47].

Such developments are currently lacking in Asia. As aforementioned, it should not be assumed that interventions demonstrated to be effective in Western cultures will be similarly effective in Asian cultures, especially those concerning suicidality. Culture plays an important role in determining risk and protective factors for suicidality, which informs targeted assessment and intervention strategies [44]. Asian suicide attempters are more likely to overdose on prescribed and over-the-counter medications instead of using firearms in their suicide attempts [48], as compared to Western samples, and Asian suicide attempters also endorse different views on the lethality of suicide methods [49].

Mindfulness interventions have been used to treat various psychological problems such as anxiety and depression [50-52]. Mindfulness practice reduces psychological distress while optimizing psychological functioning among young adults [53] by enhancing positive affect and lowering negative affect [51]. Large scale empirical research investigating the evidence base for mindfulness interventions in Asian samples seems to have gained momentum in the last few years [52]. Depression is a common psychiatric illness in Asia. Asians suffering from depression often experience maladaptive ruminations [54] and would be suitable for mindfulness-based therapies, which have been shown to contribute to significant reductions in maladaptive rumination [55]. Furthermore, youths are often affected by problems including low self-esteem [56], poor weight control [57], eating problems [58], Internet addiction [59], and chronic diseases including dermatitis [60] and asthma [61]. Mindfulness-based therapy shows evidence in improving self-esteem [62], weight control [63,64], eating problems [65], Internet addiction [66], and chronic diseases in Asian youths [67], and holds promise for use with Asian youths to enhance their overall wellbeing and resilience and reduce their vulnerability to suicidality [45]. Recent studies have drawn links between resilience, suicidality [44,68], and mindfulness practice for Asian populations [45,68]. In Asia, the stigma related to mental illness and suicidality may hinder help-seeking behavior in youths. This issue further increases their vulnerability to suicide risk [4]. These at-risk youths might prefer to access community interventions such as self-help on electronic platforms delivered using smartphone apps [20] rather than face-to-face therapy. Such apps offer an alternative delivery medium that is also cost effective [53]. The accessibility of such apps may enhance our efforts in primary prevention, and mental health promotion, aligned with recent research in Singapore. A recent study in Singapore highlighted the need for mental health promotion to reduce stigma related to psychiatric illnesses and enhance psychological wellbeing [45]. Recent research indicates that preventative mental health care involves enhancing resilience and promoting protective factors, which includes mindfulness-based interventions for emotional regulation [44,45,53].

There are many smartphone apps currently available that are marketed as mindfulness apps. A search using the search term “mindfulness-based iPhone Applications” from November 2013 yielded 808 results. This number is consistent with earlier research informed by a search for “mindfulness” conducted on iTunes and Google Applications for mindfulness training [36]. Such apps were reviewed by experts. However, the utility among Asian youth consumers remains unclear. Widespread implementation of self-help mindfulness interventions could be premature without salient evidence and scientific scrutiny for use by the intended population [69]. Youths can be impressionable consumers, and principles of rigorous scientific enquiry should be applied to explore therapeutic benefits of such apps [70]. Unfortunately, the utility of such apps for suicidality in Asian youths remains largely unexamined. Research aimed at examining low-cost smartphone apps that are efficacious as a therapeutic tool for suicidality in Asian youths would add significantly to the current literature [71]. Considering the heightened suicide risk uncovered by recent research with Asian youths [4], and the need for early prevention [45], research is needed to explore alternative ways to deliver effective interventions that are also cost effective and easily accessible. The aim of this paper is to review research relating to the evidence base for smartphone apps that can be used for mindfulness intervention for suicidality in Asian youths.

Methods

The inclusion criteria for this review were: publications in peer-reviewed journals from 2007 to 2017 with usage of search terms namely “smartphone application” and “mindfulness.” Databases included PSYCINFO, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, and PubMed. The papers were retrieved if they related to interventions via smartphone apps for mindfulness interventions. The structured proforma for evaluating eligibility for inclusion involved the following: recent papers that contain original work published in peer-reviewed journals after the year 2007; papers related to usage of a smartphone app by clinicians for therapeutic purposes and considered by an experienced Asian clinician to be of clinical utility with suicidal youths in Asia.

The focus was on recently published papers in peer-reviewed journals that fit the inclusion criteria and were relevant to smartphone apps that can be used for mindfulness intervention for suicidal youths in Asia. The main reason for the exclusion of articles was the fact that papers did not refer to the use of smartphone apps by clinicians for therapeutic purposes.

Results

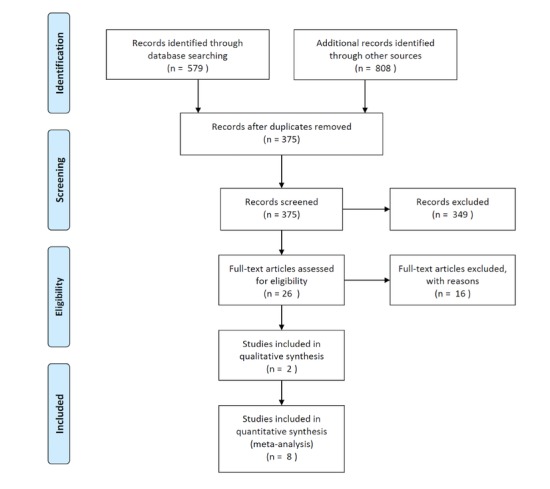

The PSYCINFO database was initially used to identify peer-reviewed papers with the inclusion criteria named above; this yielded 375 results when all search terms were used. From the original search results, the abstracts were screened, and 14 full text papers from peer-reviewed journals were then downloaded and assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow chart [72]. Ten recent papers deemed to be suitable were included in the current review, with a focus on papers published in the last 5 years. The results of the review are presented in Multimedia Appendix 1. A review of papers in Multimedia Appendix 1 shows a lack of convincing evidence of the efficacy of smartphone apps that can be used for suicide interventions for Asian youths.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Discussion

In summary, a review of papers presented in Multimedia Appendix 1 shows a lack of convincing evidence of the efficacy of smartphone apps that can be used for suicide interventions for Asian youths. A review of 15 randomized controlled trials, including 4 mindfulness-based interventions, indicates that mindfulness interventions significantly improve levels of mindfulness and depressive symptoms [69]. However, effect sizes were small to medium. There were high drop-out rates and few trials were adequately powered. Another recent study examined an app with Spanish features with a large sample size but employed statistical analyses that did not produce convincing evidence [73]. Other studies only reviewed apps [13,53,74] and did not test them on the intended users. Another study that examined mindfulness-based interventions found significant effects on well-being, stress, anxiety, depression, and mindfulness, but had a low representation of Asian youths [75]. Another study found significantly increased positive affect and decreased depression but no statistically significant difference in satisfaction with life or negative affect, and again this study had low representation of Asian youths in the sample [76]. A study on Chinese youths [77] found that an online mindfulness intervention had a significant effect on overall mental well-being and mindfulness with no specific mention of suicidality. Except Larsen et al [13], the apps in other studies were developed to address symptoms of mental disorders related to suicidality. These symptoms included depression and anxiety. In summary, the extent of generalizability of such findings to suicidality in Asian youths remains questionable.

The research reviewed in Multimedia Appendix 1 indicated that considerations for future research should include interventions lasting more than 10 days that had more than one postintervention measurement [76]. To reduce drop-out rates, reminders should be sent to users [69]. Researchers should carefully consider power and sample size and ensure robustness in statistical analyses.

There is currently a lack of interactive self-care apps available to Asian users that incorporate explicit delineation of the scope or initial screening for suitability, or offering targeted guidance, regarding management of suicidal crises [74]. Few of the apps currently on the market included content aimed at encouraging professional help-seeking or had an explicit mention of the theoretical or empirical basis of interventions. This gap needs to be addressed by partnerships between scholars, software engineers, and specialists in biomedical informatics to develop, test, and refine appropriate interfaces and apps. When designing such a mindfulness app, features to be considered include: the evidence base supporting use of mindfulness techniques in Asia; and the consideration of all the aforementioned issues, such as inclusion of explicit delineation of the scope or initial screening for suitability, targeted guidance, linking users with professional help-seeking, or explicit mention of the theoretical or empirical basis of mindfulness interventions. Specifically, mindfulness features in the app may include: breathing, body scanning, sitting meditations, walking meditations, loving kindness meditations, thoughts and emotion focus, mountain meditation, lake meditation, and 3-minute breathing spaces [53]. The content of apps for suicidality should contain at least one interactive suicide prevention feature (eg, safety planning, facilitating access to crisis support) and contain at least one strategy consistent with the evidence base or relevant best-practice guidelines [13]. Potentially harmful content, such as listing lethal access to means or encouraging risky behavior in a crisis, should be carefully screened and eliminated. Psychoeducational components to reduce the stigma related to suicidality and mental illnesses could be incorporated [44], together with monitoring of moods and stressors or other suicide triggers [45]. Youths are adversely affected by many psychosocial stressors, such as interpersonal stress which triggers suicidal ideation [78]; such triggers should be carefully assessed and addressed [4].

Another consideration is that suicidal Asian youths are not a homogenous group [4]. Suicide risk assessment needs to be conducted with consideration of risk and protective factors [45]. Therapeutic needs must be considered before clinicians decide on suitability for the use of a mindfulness app with their patients. Clinicians should carefully examine the prevailing code of ethics in working with suicidal clients to ensure best practices are observed [4,44]. This approach may include a comprehensive suicide risk assessment before deciding on the best intervention for the client [45]. Other factors to consider include defining the primary therapeutic goal and outcome (eg, reduced intensity or frequency of suicidal ideation, reduced lethality [4,44], or reduced frequency of repeated suicide attempts [45]) and monitoring the therapeutic gains progressively. It is unclear if suicide risk screening and monitoring using a smartphone app could replace face-to-face assessment conducted by an experienced clinician, but the prevailing code of ethics and professional best practices do not currently support this [4,44,45], especially when the evidence base is not clearly demonstrated.

A limitation of the review stems from the inconsistencies of the study types included in the review. Narrative reviews were included to inform the context but should be excluded because they are challenging to compare across study types. This issue further highlights the paucity of research in this area. Future research could focus on empirical studies and randomized controlled trials with Asian samples that conform to CONSORT guidelines [79]. Further research is also needed to examine the parametrization of the characteristics of the apps and their quantitative analysis with Asian samples. In addition, it is unclear if discrepancies exist between Asian samples from developing and developed countries, which could be explored in future research. The strengths of the review include the investigation of an important clinical issue and highlighting the need for more research on this pertinent topic.

In conclusion, there is consensus that suicidal risk in youths is a rising concern, especially in Asia in recent years [4]. The potential use of smartphone apps in the delivery of mindfulness interventions tailored for suicidality in Asian youths remains promising, but the evidence base to support their use is lacking. More research is needed to address the current gaps in knowledge and to provide an evidence base for the implementation of smartphone technologies. Developing mobile tools for young suicidal users requires careful ethical consideration regarding the patient-practitioner relationship, the logic of self-surveillance, prevailing codes of ethics, and overall best practices. More rigorous research and evaluations are needed to ascertain the efficacy of, and establish evidence for, best practices for the usage of such smartphone apps [40].

Acknowledgments

Administrative support and publication cost for this work was funded by the James Cook University Internal Research Grant IRG20170005.

Summary of evidence.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Lynch MA, Howard PB, El-Mallakh P, Matthews JM. Assessment and management of hospitalized suicidal patients. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2008 Jul;46(7):45–52. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20080701-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [2018-05-04]. Preventing suicide: A global imperative http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2E77040BC0ACE689271D626737FDDA0E?sequence=1 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apter A, Bursztein C, Bertolote J, Fleishmann A, Wasserman D. Young people and suicide. Suicide on all continents in the young. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. The Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention. A Global Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choo CC, Harris KM, Chew PK, Ho RC. What predicts medical lethality of suicide attempts in Asian youths? Asian J Psychiatr. 2017 Oct;29:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.05.008. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1876-2018(17)30148-X .S1876-2018(17)30148-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasserman D, Cheng Q, Jiang G. Global suicide rates among young people aged 15-19. World Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;4(2):114–20. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1723-8617&date=2005&volume=4&issue=2&spage=114 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum RW, Nelson-Mmari K. The health of young people in a global context. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Nov;35(5):402–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.10.007.S1054139X03005378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiller J, Krupinski J, Burrows G, Mackenzie A, Hallenstein H, Johnstone G. Suicide Prevention: The Global Context. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. Youth suicide: The Victorian coroner's study; pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller G. The Smartphone Psychology Manifesto. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012 May;7(3):221–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691612441215.7/3/221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang MW, Ho RC. Smartphone applications providing information about stroke: Are we missing stroke risk computation preventive applications? J Stroke. 2017 Jan;19(1):115–116. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.01004. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.01004.jos-2016-01004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang MWB, Ho RCM, Cassin SE, Hawa R, Sockalingam S. Online and smartphone based cognitive behavioral therapy for bariatric surgery patients: Initial pilot study. Technol Health Care. 2015;23(6):737–744. doi: 10.3233/THC-151026.THC--1-THC1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Smartphone application for multi-phasic interventional trials in psychiatry: technical design of a smart server. Technol Health Care. 2017;25(2):373–375. doi: 10.3233/THC-161287.THC1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang MWB, Chan S, Wynne O, Jeong S, Hunter S, Wilson A, Ho RCM. Conceptualization of an evidence-based smartphone innovation for caregivers and persons living with dementia. Technol Health Care. 2016 Sep 14;24(5):769–773. doi: 10.3233/THC-161165.THC1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen ME, Nicholas J, Christensen H. A systematic assessment of smartphone tools for suicide prevention. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152285. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152285 .PONE-D-15-46158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payne HE, Lister C, West JH, Bernhardt JM. Behavioral functionality of mobile apps in health interventions: a systematic review of the literature. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015 Feb;3(1):e20. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3335. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2015/1/e20/ v3i1e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho RCM, Mak K, Chua ANC, Ho CSH, Mak A. The effect of severity of depressive disorder on economic burden in a university hospital in Singapore. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013 Aug;13(4):549–559. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2013.815409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy JL, Altar CA, Taylor DL, Degtiar I, Hornberger JC. The social and economic burden of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014 Mar;29(2):63–76. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32836508e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery A, Metraux S, Culhane D. Rethinking homelessness prevention among persons with serious mental illness. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2013;7(1):58–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2012.01043.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang M, Cheow E, Ho CS, Ng BY, Ho R, Cheok CCS. Application of low-cost methodologies for mobile phone app development. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2014;2(4):e55. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3549. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2014/4/e55/ v2i4e55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Moodle: The cost effective solution for Internet cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT) interventions. Technol Health Care. 2017;25(1):163–165. doi: 10.3233/THC-161261.THC1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal NK. Applying mobile technologies to mental health service delivery in South Asia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012 Sep;5(3):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.12.009.S1876-2018(11)00164-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brian RM, Ben-Zeev D. Mobile health (mHealth) for mental health in Asia: objectives, strategies, and limitations. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014 Aug;10:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.04.006.S1876-2018(14)00118-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burns JM, Davenport TA, Durkin LA, Luscombe GM, Hickie IB. The Internet as a setting for mental health service utilisation by young people. Med J Aust. 2010 Jun 7;192(11 Suppl):S22–30. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03688.x.bur11029_fm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrer L, Gulliver A, Chan JKY, Batterham PJ, Reynolds J, Calear A, Tait R, Bennett K, Griffiths KM. Technology-based interventions for mental health in tertiary students: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013 May;15(5):e101. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2639. http://www.jmir.org/2013/5/e101/ v15i5e101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenny R, Dooley B, Fitzgerald A. Developing mental health mobile apps: exploring adolescents' perspectives. Health Informatics J. 2016 Jun;22(2):265–275. doi: 10.1177/1460458214555041.1460458214555041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seko Y, Kidd S, Wiljer D, McKenzie K. Youth mental health interventions via mobile phones: a scoping review. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014 Sep;17(9):591–602. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drum DJ, Denmark AB. Campus suicide prevention: bridging paradigms and forging partnerships. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):209–221. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.712841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shand FL, Ridani R, Tighe J, Christensen H. The effectiveness of a suicide prevention app for indigenous Australian youths: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:396. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-396. http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/14//396 .1745-6215-14-396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang MW, Ho CS, Fang P, Lu Y, Ho RC. Usage of social media and smartphone application in assessment of physical and psychological well-being of individuals in times of a major air pollution crisis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2014 Mar 25;2(1):e16. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2827. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2014/1/e16/ v2i1e16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho RC, Zhang MW, Ho CS, Pan F, Lu Y, Sharma VK. Impact of 2013 south Asian haze crisis: study of physical and psychological symptoms and perceived dangerousness of pollution level. BMC Psychiatry. 2014 Mar 19;14:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-81. http://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-14-81 .1471-244X-14-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preziosa A, Grassi A, Gaggioli A, Riva G. Therapeutic applications of the mobile phone. Br J Guid Counc. 2009 Aug;37(3):313–325. doi: 10.1080/03069880902957031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kazemi DM, Cochran AR, Kelly JF, Cornelius JB, Belk C. Integrating mHealth mobile applications to reduce high risk drinking among underage students. Health Education Journal. 2013 Feb 19;73(3):262–273. doi: 10.1177/0017896912471044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu H, Frauendorfer D, Rabbi M, Mast M, Chittaranjan G, Campbell A, Gatica-Perez D, Choudhury T. StressSense: detecting stress in unconstrained acoustic environments using smartphones. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing; 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing; 2012; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rachuri K, Musolesi M, Mascolo C, Rentfrow P, Longworth C, Aucinas A. EmotionSense: a mobile phones based adaptive platform for experimental social psychology research. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing; 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing; 2012; USA. 2010. pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: a qualitative review. Addict Behav. 2008 Aug;33(8):994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18538484 .S0306-4603(08)00083-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reger MA, Gahm GA. A meta-analysis of the effects of Internet- and computer-based cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety. J Clin Psychol. 2009 Jan;65(1):53–75. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donker T, Petrie K, Proudfoot J, Clarke J, Birch M, Christensen H. Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Nov 15;15(11):e247. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2791. http://www.jmir.org/2013/11/e247/ v15i11e247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuhn E, Greene C, Hoffman J, Nguyen T, Wald L, Schmidt J, Ramsey KM, Ruzek J. Preliminary evaluation of PTSD Coach, a smartphone app for post-traumatic stress symptoms. Mil Med. 2014 Jan;179(1):12–18. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner-McGrievy G, Tate D. Tweets, Apps, and Pods: Results of the 6-month Mobile Pounds Off Digitally (Mobile POD) randomized weight-loss intervention among adults. J Med Internet Res. 2011 Dec;13(4):e120. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1841. http://www.jmir.org/2011/4/e120/ v13i4e120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wayne N, Ritvo P. Smartphone-enabled health coach intervention for people with diabetes from a modest socioeconomic strata community: single-arm longitudinal feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2014 Jun;16(6):e149. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3180. http://www.jmir.org/2014/6/e149/ v16i6e149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguilera A, Muñoz RF. Text messaging as an adjunct to CBT in low-income populations: a usability and feasibility pilot study. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011 Dec 01;42(6):472–478. doi: 10.1037/a0025499. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25525292 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Tapping onto the potential of smartphone applications for psycho-education and early intervention in addictions. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:40. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00040. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Smartphone applications for immersive virtual reality therapy for Internet addiction and internet gaming disorder. Technol Health Care. 2017;25(2):367–372. doi: 10.3233/THC-161282.THC1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang MW, Tsang T, Cheow E, Ho CS, Yeong NB, Ho RC. Enabling psychiatrists to be mobile phone app developers: insights into app development methodologies. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2014;2(4):e53. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3425. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2014/4/e53/ v2i4e53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choo CC, Harris KM, Chew PKH, Ho RC. Does ethnicity matter in risk and protective factors for suicide attempts and suicide lethality? PLoS One. 2017 Apr;12(4):e0175752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175752. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175752 .PONE-D-16-44180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choo C, Diederich J, Song I, Ho R. Cluster analysis reveals risk factors for repeated suicide attempts in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014 Apr;8:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.10.001. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/31006/ S1876-2018(13)00308-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durham DBT, Inc. 2017. DBT Diary Card & Skills Coach https://itunes.apple.com/au/app/dbt-diary-card-skills-coach/id479013889?mt=8 .

- 47.Rizvi SL, Dimeff LA, Skutch J, Carroll D, Linehan MM. A pilot study of the DBT coach: an interactive mobile phone application for individuals with borderline personality disorder and substance use disorder. Behav Ther. 2011 Dec;42(4):589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.003.S0005-7894(11)00050-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho CSH, Ong YL, Tan GHJ, Yeo SN, Ho RCM. Profile differences between overdose and non-overdose suicide attempts in a multi-ethnic Asian society. BMC Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 08;16(1):379. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1105-1. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-016-1105-1 .10.1186/s12888-016-1105-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mak KK, Ho CSH, Zhang MWB, Day JR, Ho RCM. Characteristics of overdose and non-overdose suicide attempts in a multi-ethnic Asian society. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013 Oct;6(5):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.011.S1876-2018(13)00093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chittaro L, Vianello A. Evaluation of a mobile mindfulness app distributed through on-line stores: a 4-week study. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2016 Feb;86:63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2015.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plaza I, Demarzo MMP, Herrera-Mercadal P, García-Campayo J. Mindfulness-based mobile applications: literature review and analysis of current features. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2013;1(2):e24. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2733. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2013/2/e24/ v1i2e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong SYS, Mak WWS, Cheung EYL, Ling CYM, Lui WWS, Tang WK, Wong RLP, Lo HHM, Mercer S, Ma HSW. A randomized, controlled clinical trial: the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on generalized anxiety disorder among Chinese community patients: protocol for a randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2011 Nov 29;11:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-187. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-11-187 .1471-244X-11-187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luoma JB, Villatte JL. Mindfulness in the treatment of suicidal patients. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012 Jan 05;19(2):265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.12.003. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22745525 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu Y, Tang C, Liow CS, Ng WWN, Ho CSH, Ho RCM. A regressional analysis of maladaptive rumination, illness perception and negative emotional outcomes in Asian patients suffering from depressive disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014 Dec;12:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.014.S1876-2018(14)00147-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McIndoo CC, File AA, Preddy T, Clark CG, Hopko DR. Mindfulness-based therapy and behavioral activation: a randomized controlled trial with depressed college students. Behav Res Ther. 2016 Feb;77:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.012.S0005-7967(15)30076-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mak K, Pang JS, Lai C, Ho RC. Body esteem in Chinese adolescents: effect of gender, age, and weight. J Health Psychol. 2013 Jan;18(1):46–54. doi: 10.1177/1359105312437264.1359105312437264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quek Y, Tam WWS, Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017 Jul;18(7):742–754. doi: 10.1111/obr.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lai C, Mak K, Pang JS, Fong SSM, Ho RCM, Guldan GS. The associations of sociocultural attitudes towards appearance with body dissatisfaction and eating behaviors in Hong Kong adolescents. Eat Behav. 2013 Aug;14(3):320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.05.004.S1471-0153(13)00047-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mak K, Lai C, Watanabe H, Kim D, Bahar N, Ramos M, Young KS, Ho RCM, Aum N, Cheng C. Epidemiology of Internet behaviors and addiction among adolescents in six Asian countries. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014 Nov;17(11):720–728. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chernyshov PV, Ho RC, Monti F, Jirakova A, Velitchko SS, Hercogova J, Neri E. An international multi-center study on self-assessed and family quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23(4):247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu Y, Ho R, Lim TK, Kuan WS, Goh DYT, Mahadevan M, Sim TB, Ng T, van BHPS. Psychiatric comorbidities in Asian adolescent asthma patients and the contributions of neuroticism and perceived stress. J Adolesc Health. 2014 Aug;55(2):267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.007.S1054-139X(14)00019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hjeltnes A, Molde H, Schanche E, Vøllestad J, Lillebostad SJ, Moltu C, Binder P. An open trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for young adults with social anxiety disorder. Scand J Psychol. 2017 Feb;58(1):80–90. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Forman EM, Butryn ML. A new look at the science of weight control: how acceptance and commitment strategies can address the challenge of self-regulation. Appetite. 2015 Jan;84:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25445199 .S0195-6663(14)00474-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turner T, Hingle M. Evaluation of a mindfulness-based mobile app aimed at promoting awareness of weight-related behaviors in adolescents: a pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017 Apr 26;6(4):e67. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6695. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2017/4/e67/ v6i4e67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Atkinson MJ, Wade TD. Mindfulness-based prevention for eating disorders: a school-based cluster randomized controlled study. Int J Eat Disord. 2015 Nov;48(7):1024–1037. doi: 10.1002/eat.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim H. Exercise rehabilitation for smartphone addiction. J Exerc Rehabil. 2013;9(6):500–505. doi: 10.12965/jer.130080. http://www.e-jer.org/journal/view.php?year=2013&vol=9&page=500 .jer-9-6-500-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thompson M, Gauntlett-Gilbert J. Mindfulness with children and adolescents: effective clinical application. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;13(3):395–407. doi: 10.1177/1359104508090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mani M, Kavanagh DJ, Hides L, Stoyanov SR. Review and evaluation of mindfulness-Based iPhone apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015 Aug 19;3(3):e82. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4328. http://mhealth.jmir.org/2015/3/e82/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Forder L, Jones F. Can mindfulness and acceptance be learnt by self-help?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness and acceptance-based self-help interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014 Mar;34(2):118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.001.S0272-7358(14)00002-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev. 2010 Mar;32:56–69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20354039 .mxq004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aguilera A, Muench F. There's an app for that: information technology applications for cognitive behavioural pracitioners. Behav Ther. 2012 Apr;35(4):65–73. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25530659 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Plaza García García I, Sánchez CM, Espílez ÁSá, García-Magariño I, Guillén GA, García-Campayo J. Development and initial evaluation of a mobile application to help with mindfulness training and practice. Int J Med Inform. 2017 Dec;105:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.05.018.S1386-5056(17)30167-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kumar S, Mehrotra S. Free mobile apps on depression for Indian users: a brief overview and critique. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017 Aug;28:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spijkerman MPJ, Pots WTM, Bohlmeijer ET. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: a review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016 Apr;45:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.009. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0272-7358(15)30062-3 .S0272-7358(15)30062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Howells A, Ivtzan I, Eiroa-Orosa FJ. Putting the “app” in happiness: a randomised controlled trial of a smartphone-based mindfulness intervention to enhance wellbeing. J Happiness Stud. 2014 Oct 29; doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9589-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mak WWS, Chan ATY, Cheung EYL, Lin CLY, Ngai KCS. Enhancing Web-based mindfulness training for mental health promotion with the health action process approach: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015 Jan 19;17(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3746. http://www.jmir.org/2015/1/e8/ v17i1e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Buitron V, Hill RM, Pettit JW, Green KL, Hatkevich C, Sharp C. Interpersonal stress and suicidal ideation in adolescence: an indirect association through perceived burdensomeness toward others. J Affect Disord. 2016 Jan 15;190:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.077.S0165-0327(15)30117-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e126. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1923. http://www.jmir.org/2011/4/e126/ v13i4e126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of evidence.