Abstract

Background:

Cordylobia anthropophaga, is responsible for nodular cutaneous myiasis in sub-Saharan Africa. The fly has long been limited to tropical Africa except for Asir Province, Saudi Arabia. Al Baha Province; north of Asir has an ecological pattern close to that dominant in subtropical Africa. The Southern parts of Saudi Arabia, including Al Baha, are considered part of the Afro-tropical zoogeographical belt where C. anthropophaga is dominant. A case, with cutaneous nodular lesions, was presented to us, where comprehensive investigations were done to establish the diagnosis and to relate it to the known epidemiological background.

Materials and methods:

A thorough history taking, comprehensive clinical examination and an intensive parasitological examination on a viable larva recovered from the cutaneous lesions, were performed. Taxonomic identification of the larva was done based on various criteria including shape, size, cuticle spine pattern and the posterior spiracles of the recovered larva.

Results:

We report a case of cutaneous myiasis, caused by Cordylobia anthropophaga, indigenously acquired in Al-Baha. The recovered larva was identified as the third instar of C. anthropophaga. With no history of travel to Africa or to Asir, along with a comprehensive epidemiological assessment, an autochthonous pattern of transmission was confirmed.

Conclusion:

We present a new focus of autochthonous transmission of C. anthropophaga in Saudi Arabia suggesting a need for an epidemiological reassessment. We also propose considering Cordylobia myiasis as a differential diagnosis in furuncular skin lesions, even in individuals with no history of traveling to Africa.

Keywords: Myiasis, Cordylobia anthropophaga, Autochthonous transmission, Baha-Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

The African tumbu fly, Cordylobia anthropophaga, is responsible for cutaneous furuncular myiasis in both humans and animals, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The fly prefers warm and humid environment; thus, myia-sis, in temperature regions of Africa, take places in summer, while being year round in the tropics. C. anthropophaga has many natural reservoirs, therefore, proximity to domestic or sylvatic animals is a prerequisite for human infestation [2].

Although cases of myiasis, due to C. anthropophaga, are common in travelers returning from endemic areas [3,4,5], the fly itself has long been limited to tropical Africa [1]. In Saudi Arabia, little is known about human cutaneous myiasis in general, and C. anthropophaga infestation in particular. In 1980 and early 1990s, indigenous cases of myiasis, due to C. anthropophaga, were reported three times [6,7,8] exclusively in the province of Asir, South Western Saudi Arabia making it the sole endemic focus outside Africa. Two isolated reports suggested that C. anthropophaga myiasis might be indigenously acquired in Southern Europe; Spain and Portugal [9,10].

Al Baha Province; 300 km north of Asir has an ecology that is close to the dominant ecological pattern of subtropical Africa. It represents an environment with a rainy, humid climate and surrounding forests with potential hosts [11], which is conductive for the fly.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published report of indigenously acquired cases of Cordylobia anthro-pophaga myiasis, from Al Baha, Saudi Arabia.

2. Case report

A 10-year old Saudi female child; presented, mid-September 2013, at the pediatrics clinic of King Abdulaziz university hospital, with two boil-like nodular lesions of three-weeks duration. A history of an older girl 12 years old, not presenting to us, having the same nodular type of lesions was given. Both sisters contracted infection while in vacation in a farm in suburban outskirts of Al-Baha city, South western of Saudi Arabia. There was no history of traveling abroad or to other places in the country. The lesions started as pruritic papules which then developed into slightly painful nodules within few days. There was no fever but a sense of malaise. They sought after medical help, in a local polyclinic, where lesions were misdiagnosed as frunculosis. Broad spectrum antibiotics were advised, an approach that didn’t bring relief. The family decided to seek a second medical opinion in their city of residence, Jeddah, where they presented to us. Clinical examination revealed two nodules on the left axilla and the back of the neck (Fig. 1). Each nodule had a 1 cm diameter with ill-demarcated edges and a central punctum. There were little tenderness and scanty serous exudates. No regional or systemic lymphadenopathy was observed. The case was diagnosed as fruncular cutaneous myiasis when viable larvae (Fig. 2) were painlessly removed using forceps and gentle squeezing.

Fig. 1.

A nodular skin lesion with a central punctum in a covered place (back of the neck) characteristic of Cordylobia anthropophaga infestation.

Fig. 2.

A larva recovered from the skin lesion.

The shape of the extracted larvae excludes all other candidates except Cordylobia anthropophaga. Cephaloskeleton and posterior spiracles was dissected and examined microscopically after the standard procedures of fixation, dehydration and clearing. The larvae were identified as typical third-instars of C. anthropophaga by size, oval body, spine pattern and posterior spiracles morphology. They were creamy white with a pointed anterior and a blunt posterior end. One larva was about 7 mm long and 3 mm in width while the other one was 12 mm × 4 mm. The body consisted of twelve clearly marked segments covered with backwardly directed black spines (Fig. 3). The morphology of larval posterior spiracles (Fig. 4) was the most indicative of the species. They were not widely separated with a weakly sclerotized, closed peritreme and three slightly sinuous slits (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

A cuticle spine pattern showing numerous scattered backwardly directed black spines characteristic of Cordylobia anthropophaga

Fig. 4.

Posterior spiracles, of the recovered larva, showing a weakly sclerotized, closed peritreme and three slightly sinuous slits; a pattern characteristic of 3rd. instar larva of Cordylobia anthropophaga

Fig. 5.

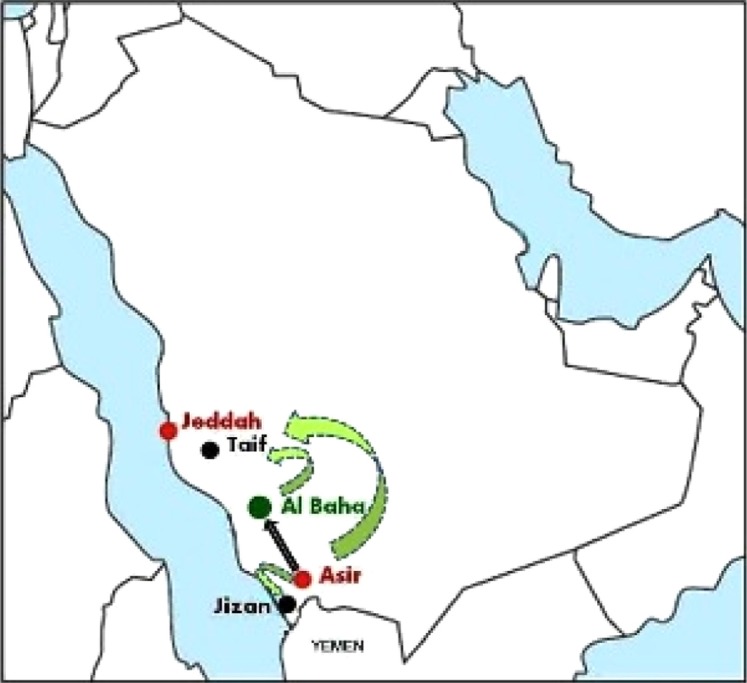

A virtual map showing hypothetical directions (Al Bahato Al Taif, Asir to Al Taif and Asir to Jizan) for future Cordylobia anthropophaga transmission (dotted green arrows) of in Saudi Arabia. The direction of transmission verified in our study (black solid arrow) from Asir to Al Baha is also demonstrated. Jeddah, where the case has been presented, is showing on the map.

3. Discussion

Very little information is available to date concerning the epidemiology of Cordylobia anthropophaga in Saudi Arabia. Reporting a new focus of autochthonous transmission, of such a fly, is a significant input to an epidemiological archive that has not been updated since 1992.

The history given by the presenting case, together with the observed clinical signs, had many aspects that are typical of C. anthropophaga infestation. Being a child from a non-endemic area traveling to a farm that has an animal shed, compel an exceptional risk of infestation. The risk is probably due to relatively thin skin, lower immunity with the lack of exposure and close contact with rodents and dogs; the animal reservoirs of the fly [2]. Clinically, multiple nodular lesions, with a central punctum, in covered places of the body without fever or regional lymphadenopathy were suggestive of Cordylobia myiasis. Multiple lesions on covered places like trunk, buttocks, and axilla is a common finding, in that kind of infestation, as adult Cordylobia tend to lay ova on soiled clothes [12]. In our case, the axilla and back of the neck are considered covered sites, in a female dressed in custom clothing related to local cultural traditions.

Easy extraction of larvae, as tumbu larvae do not have abdominal hooklets [13], and recovery of one larva per lesion was more suggestive of C. anthropophaga infestation. However, an absent history of traveling abroad or to Asir together with a missing case record from “Al-Baha” were against that tentative diagnosis. As myiasis is typically based on larval characteristics, taxonomic study confirmed the C. anthropophaga infestation and the absent travel history turned into evidence of autochthonous transmission in Saudi Arabia.

While novel, reporting a case of myiasis by C. anthro-pophaga in this region of Saudi Arabia, is not a unique epidemiological finding. The Southern parts of the Arabian Peninsula are considered, by some authors, a part of the Afro-tropical zoogeographical belt [14], where C. anthropophaga is traditionally common. Al-Baha Province is situated very close to the northern limit of that belt [15].

Regions of Saudi Arabia, having similar ecological conditions, situated close to the two confirmed foci of C. anthropophaga (Asir, Al-Baha), might represent future foci of transmission. The environmental attributes related to temperature and precipitations have a major impact on C. anthropophaga occurrence/distribution [1]. Al-Taif province, about 200 km north to Al-Baha, and is considered the Northern limit of the Afrotropical region [16], has close ecological conditions to that in Al-Baha. The weather system in Taif region is generally arid with an annual mean temperature of 19.8 °C and a monthly relative humidity peak at 60% in January. The rainfall in the region is erratic and irregular with an annual average of 102.4 mm/day [17]. This climatic conditions, along, with other environmental factors are permissive to diverse plant communities [18], making agriculture one of the main human activities of that region. With these conductive ecological conditions, C. anthropophaga might spread northwards to Taif region. Parts of the Jazan province, in the Eastern Sarawat mountain, with humid hot climate and with annual precipitation rate >300 mm served as a permissive environment for malaria and rift-valley fever mosquito vectors [19]. Same areas could also represent a potential focus for C. anthropophaga future spread.

In conclusion, our study confirms an autochthonous pattern of transmission, of C. anthropophaga in Saudi Arabia, with a slow but continuous expansion in what is considered an Afro-tropical zoogeographical belt in the country. This finding urges an epidemiological reassessment of C. anthropophaga in Saudi Arabia. Clinical staff will have to consider Cordylobia myiasis in furuncular skin lesions, even in individuals without travel history to Africa.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of Prof. Mahmmoud Fouad and Dr. Suhaib Fatani and Mr. Abdulaziz Bernawy for attentive support and technical assistance.

References

- [1].Zumpt F. The tumbu fly, Cordylobia anthropophaga (Blanchard), in Southern Africa. S Afr Med J. 1959;33:862–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].James AS, Stevenson J. Cutaneous myiasis due to tumbu fly. Arch Emerg Med. 1992;9:58–61. doi: 10.1136/emj.9.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hasegawa M, Harada T, Kojima Y, Nakamura A, Yamada Y, Kadosaka T, et al. An imported case of furuncular myiasis due to Cordylobia anthropophaga which emerged in Japan. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:912–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dehecq É, Nzungu PN, Cailliez J-C, Guevart E, Delhaes L, Dei-Cas E, et al. Cordylobia anthropophaga (Diptera: Calliphoridae) outside Africa: a case of furuncular myiasis in a child returning from Congo. J Med Entomol. 2009;42:187–92. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/42.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Palmieri JR, North D, Santo A. Furuncular myiasis of the foot caused by the tumbu fly, Cordylobia anthropophaga: report in a medical student returning from a medical mission trip to Tanzania. Int Med Case Rep J. 2013;6:25–8. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S44862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Büttiker W, Habayeh S, Zumpt F. Medical and applied zoology in Saudi Arabia, first record of the tumbu Fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga [Blanchard]), (Diptera: Fam.Calliphoridae) Fauna Saudi Arab. 1980;2:440–3. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Omar MS, Abdalla RE. Cutaneous myiasis caused by tumbu fly larvae, Cordylobia anthropophaga in southwestern Saudi Arabia. Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;43:128–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sundharam JA, Al-Gamal MN. Myiasis in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 1994;14:352. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1994.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Laurence BR, Herman FG. Tumbu fly (Cordylobia) infection outside Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1973;67:888. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(73)90027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Curtis SJ, Edwards C, Athulathmuda C, Paul J. Case of the month: cutaneous myiasis in a returning traveler from the Algarve: first report of tumbu maggots, Cordylobia anthropophaga, acquired in Portugal. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:236–7. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.028365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].The Saudi Network. Al Baha city profile. 2014. [accessed 12.11.14]. http://www.the-saudi.net/saudi-arabia/baha/Al%20Baha%20City%20-%20Saudi%20Arabia.htm .

- [12].Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:79–105. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00010-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wolf R, Marcus B, Orion E, Matz H. Tumbu larvae do not have abdominal hooklets and can be easily extracted. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:754–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Crosskey RW, White GB. The Afrotropical region. A recommended term in zoogeography. J Nat Hist. 1977;11:541–4. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Holzel H. Zoogeographical features of neuroptera of the Arabian peninsula. Acta Zool Fennica. 1998;209:129–40. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kaszab Z. Insect of Saudi Arabia, Coleoptera: Fam. Tenebrionidae (Part 2) Fauna Saudi Arab. 1981;3:276–401. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Farrag HF. Floristic composition and vegetation-soil relationships in Wadi Al-Argy of Taif region, Saudi Arabia. Int J Plant Sci. 2012;3(8):147–57. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Abdel-Fattah RI, Ali AA. Vegetation–environment relations in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Int J Bot. 2005;1:206–11. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sallam MF, Al Ahmed AM, Abdel-Dayem MS, Abdullah MAR. Ecological Niche modeling and land cover risk areas for rift valley fever vector, Culex tritaeniorhynchus Giles in Jazan, Saudi Arabia. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]