Abstract

Regenerative medicine is a distinct major advancement in medical treatment which is based on the principles of stem cell technology and tissue engineering in order to replace or regenerate human tissues and organs and restore their functions. After many years of basic research, this approach is beginning to represent a valuable treatment option for acute injuries, chronic diseases and congenital malformations. Nevertheless, it is a little known field of research. The purpose of this review is to convey the state of the art in regenerative medicine in terms of historical steps, used strategies and pressing problems to solve in the future. This review represents a good starting point for more in-depth studies and personal research projects.

Keywords: Regenerative medicine, Stem cells, Biomaterials, Artificial organs, Tissue engineering

1. Historical background

Regenerative medicine (RM) implies the replacement or regeneration of human cells, tissue or organs, to restore or establish normal function [1].

The term “regenerative medicine” is widely considered to be coined by William Haseltine during a 1999 conference on Lake Como, in the attempt to describe an emerging field, which blent knowledge deriving from different subjects: tissue engineering (TE), cell transplantation, stem cell biology, biomechanics prosthetics, nanotechnology, biochemistry [2]. Historically, this term was found for the first time in a 1992 paper by Leland Kaiser, who listed the technologies which would impact the future of hospitals [3].

RM is considered a novel frontier of medical research, but the idea of creating artificial organs is not so recent. In 1938, a book, called “The culture of new organs”, was published and the authors were Alexis Carrell, a Nobel Prize winner for his study on vascular anastomosis, and Charles Lindbergh, the first aviator to fly across the Atlantic alone. Wondering why his sister-in-law's fatal heart condition could not be repaired surgically, Lindbergh, despite not being a professional, ended up working together with Carrell at Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research during the 1930s, where they created an artificial perfusion pump allowing the perfusion of the organs outside the body during surgery: their work was the basis for the development of the artificial heart [4].

The regeneration of body parts is a rather common phenomenon in nature; a salamander can regenerate an amputated limb in several days [5]. Humans have this ability as well, but they lose it over the years: a severed fingertip can regenerate until 11 years of age [6]. The human regeneration potential was well-known also in ancient times, as demonstrated by the myth of Prometheus: his liver was eaten by an eagle during the day and it completely regenerated itself overnight.

During the last centuries medicine has gained many successes: antibiotic therapy, anesthesia, sterilization, etc. However, there are still many pathologies which cannot be treated by preserving the affected organs, but require the resection of lesions or the repair with autologous tissues or even the replacement with allografts [7]. This is the three R's paradigm in traditional surgery with three solutions, all of which pose different problems.

When a surgeon resects an extensive part of small bowel, leading to a malabsorption syndrome, called short bowel syndrome, long-life total parenteral nutrition is imposed, threatening patient's life [8].

People suffering from high-pressure or poorly compliant bladders may need augmentation cystoplasty, which is performed by using part of small bowel. Since gastrointestinal tissues adsorb solutes rather than excrete urine, the repaired bladder is often complicated by increased mucous production, infections, metabolic disturbances, urolithiasis, perforation and even cancer [9].

As for organ replacements, in 1954, the kidney was the first organ to be substituted in a human, but between identical twins so that rejection did not arise [10]. Later, also cell transplantation was achieved: an immunodeficient patient received his sibling's bone marrow [11]. At first, transplants were relegated to research because of the adverse immunological responses, but the advent of cyclosporine in the 1980s transformed transplantations into life-saving treatments, as the risk of rejection could be drastically reduced. Nowadays, lifelong immunosuppression carries many side effects, representing one of the two big problems related to transplantations [12]. The other one is the shortage of donors, not being able to meet the ever increasing demand of organs [13]. Due to the progressively aging population, transplantations will be increasingly needed to replace end-stage diseased organs injured by age-related diseases.

All these issues are carrying with them economical and social problems: while in 1941 there were 41 workers for one retiree in the USA, now there are only three workers for one retiree, so that the common invalidating chronic diseases are bearing upon a small part of work-age citizens [14].

Therefore, medicine is facing with pressing problemswhich require an evolution of medical treatments and theregeneration of damaged tissues, “the fourth R”, could revo-lutionize modern medicine, offering the way to cure, ratherthan merely treat symptoms.

A partial list of the most relevant conquests in the his-tory of regenerative medicine is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

A partial list of firsts in RM.

| Year | First |

|---|---|

| 1968 | First cell transplantation: bone marrow transplant [11] |

| 1978 | Discovery of stem cells in human cord blood [15] |

| 1981 | First in vitro stem cell line developed from mice [16] |

| 1981 | First engineered tissue transplantation: skin [17] |

| 1996 | Creation of the first cloned animal: a sheep, named Dolly [18] |

| 1998 | Isolation of human embryonic stem cells [19] |

| 1999 | First laboratory-grown organ: an artificial bladder implanted in a patient suffering from myelomengicocele [20] |

| 2004 | Implantation of first engineered tubular organs (urine conduits) [21] |

| 2007 | Discovery of stem cells derived from amniotic fluid and placenta [22] |

| 2009 | First solid organ engineered by recycling donor liver [23] |

The later part of the article looks into the current strategies used in RM and the associated shortcomings whichdeter its liberal and convenient application in the clinicalsetting on a daily basis.

2. Current strategies used in regenerative medicine

There are substantially three different approaches topursue the objective of RM (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1.

Strategies used in regenerative medicine. There are substantially three approaches: cell-based therapy, use of engineered scaffolds and the implantation of scaffolds seeded with cells.

Cell-based therapy;

Use of either biological or synthetic materials to leadrepair processes and cell growth;

Implantation of scaffolds seeded with cells.

2.1. Cell-based therapy

Humans have complex multicellular framework withseveral types of cells specialized in particular functions. However, all cells descend from one unique cell, calledzygote. During development, cells differentiate progres-sively and acquire more and more specific tasks, while theylose their capacity for differentiating into other cells. Theability to differentiate into other cell types is defined as”cell potency” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cell potency.

| Totipotency | The ability of a single cell to produce all cells (potency possessed until 16-cell stage during blastocyst phase) |

| Pluripotency | The ability to differentiate into a cell of all three germ layers (e.g. embryonic stem cells) |

| Multipotency | Gene activation limits these cells to differentiate into multiple, but limited cell types (e.g. hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into all blood cells: erythrocytes, lymphoid cells, neutrophils, platelets, etc.) |

| Oligopotency | The ability to differentiate into limited cell types (e.g. lymphoid stem cells become either B cells or T cells) |

| Unipotency | Ability to differentiate into one single cell type (e.g. precursor cell) |

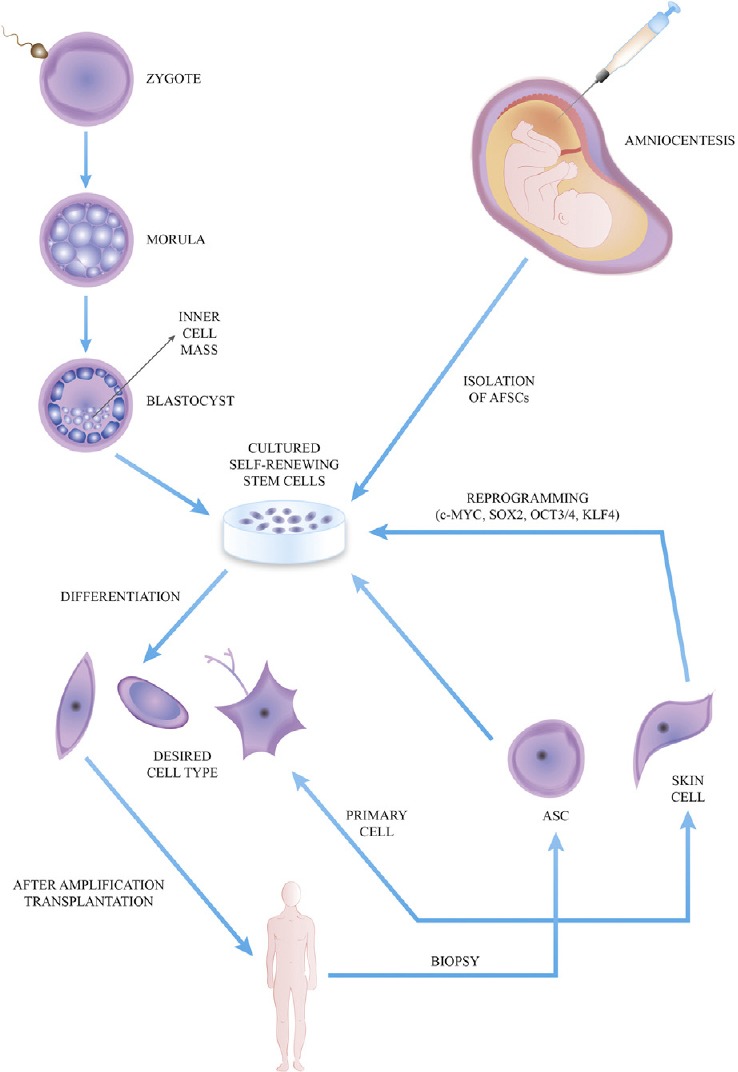

Cell therapy consists of injecting novel and healthy cellsin pathologic tissues. It can rely either on already differen-tiated cells or on undifferentiated stem cells (Fig. 2), whichcan differentiate depending on particular circumstances.

Fig. 2.

Cell therapy bases on the injection of cells obtained by different methods. Adult primary cells are taken from patient and directly implanted after expansion in vitro. Biopsied tissues contain adult stem cells (ASCs) to expand, differentiate into a specific type and implant. Adult skin cells may be reprogrammed through specific transcription factors in order to obtain induced pluripotent stem cells. Embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass of a blastocyst. At last, the amniotic fluid is a potential source for stem cells (AFSCs). Read the text for a detailed description. Abbreviations: AFSCs, amniotic fluid-derived stem cells; ASC, adult stem cell.

On the first hand, the differentiated endogenous pri-mary cells are collected by patient's specific tissues with the advantage of being ready to implant without any fur-ther manipulations, but expansion. However, it is difficultto get a considerable number of these cells in vitro, also for organs (e.g. liver) with a great replication potential invivo, as the cells lose the usual microenvironment neededto proliferate [24]. Therefore, these cells will be used lessand less in the future, even if they are not correlated withrejection and important inflammatory responses.

On the other hand, stem cells (SCs) can proliferateextensively, with the capacity of self-renewing whilethey maintain their undifferentiated state, until they areinduced to differentiate into a specific cell type [25]. SCs canbe obtained in several ways. They are autologous if derivedfrom patient, allogeneic if derived from a human donor andxenogeneic if derived from another animal.

Adult stem cells (ASCs) had been isolated from nearly allhuman adult body tissues, where their goal is to restoreoriginal tissue function after minor injuries [26]. Amongthese cells, a preeminent role is played by the bonemarrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), as theyhad been studied deeply. Using different culture protocols, they have been shown to be able to differentiate into manykinds of cells, useful to treat bone, cartilage, nervous, mus-cle, cardiovascular, blood, gastrointestinal diseases [27].

By aspirating the inner cell mass from an embryo during the blastocyst stage (5 days post fertilization), we can get embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which can proliferate exten-sively while maintaining their pluripotent state until theyare induced to differentiate into one kind of cells from all the three embryogenic germ layers (Table 3) [28]. Human ESCs can be derived from the surplus of embryos gener-ated during in vitro fertilization. Besides the huge potential, there are several issues with the use of ESCs which cannot be ignored:

Table 3.

Derivates from germ layers.

| Germ layer | Derived tissues and organs |

|---|---|

| Ectoderm | Epidermal tissues and nervous system |

| Mesoderm | Bone, blood, cartilage, muscle, urogenital system, serous membranes |

| Endoderm | GI tract, airways |

- Rejection: they are allogeneic, but immune responses can be avoided with some new developing technologies, like therapeutic cloning and adult cell reprogramming;

- Need for feeder cells for trophic support: first time feeder cells were used in mouse fibroblasts, correlated with the risk of xeno-contamination [29];

- Carcinogenesis: ESCs can develop into teratomas [30];

- Ethical and moral issues: they represent a notable source of debate, as their source is an embryo, whose development is interrupted by the aspiration.

The first recipient of these cells was a young man, who had a spinal cord injury in a car accident: he received the injection of oligodendrocytes obtained from ESCs [31].

Another strategy to obtain ESCs is the so-called therapeutic cloning or somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), which is based on the transfer of a somatic cell nucleus into an oocyte. In this way, early stage embryos are cultured to produce ESCs with the potential to become almost any adult cell types [32]. Besides being a source for RM, this technique is also the basis for cloning animals, like the famous sheep, called Dolly [18]. Through this technology, pathologic cell lines can be obtained to study the effects of some molecules in cells with specific diseases.

Autologous stem cells can also be obtained through a reprogramming of adult cells to get induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). They have the same cell potency as ESCs, so they could replace the controversial use of ESCs. The generation of iPSCs was firstly achieved by introducing a series of transcription factors into murine fibroblasts: the firsts were OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4 and c-MYC [33]. The latter, c-MYC, is an oncogene and could give rise to tumors, so it had been replaced successfully, according to different reports, using OCT4, SOX2, NANOG and LIN28 [34]. Unfortunately, in this way the process took longer and was not as efficient as the other protocol. Originally, the delivery of these transcription factors was achieved through the use of retro- and lentiviral constructs, but, since this strategy could provoke insertional mutagenesis and oncogene activation, it should be substituted by non-viral-based methods or by the adenovirus-based transient transfection without genomic integration [35]. Recently, iPSCs were obtained in mice in vivo without the use of a Petri's dish [36].

Another important feature of iPSCs is their use for the generation of disease-specific lines (for example, affected by Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, diabetes mellitus type I) to study disease mechanisms and drug screening [37].

A human clinical trial with iPSCs is being conducted at Japanese RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology [38]. The first recipient was a 70-year-old woman affected by exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD), whose skin cells were taken and induced to differentiate into retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells, which were used to create a small monolayered RPE sheet to implant into the patient's eye, without any biomaterials.

Lastly, scientists can obtain SCs from amniotic fluid and placenta by amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling in the developing fetus or from the placenta at birth, the so-called amniotic fluid-derived stem cells (AFSCs) [22]. These cells are multipotent and do not develop neoplasms. A range of possible clinical applications has been described in the literature. For example, AFSCs from cell banks can represent a lifelong autologous source for heart-valve replacements [39]. Since they are very promising, they have been studied deeply in the recent past, but no human clinical trials have been performed yet.

All the advantages and disadvantages related to the different cell types are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Advantages and disadvantages of cell types used in RM.

| Cell type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiated endogenous primary cells | No tissue rejection Reduced inflammatory response |

Difficult expansion because of in vitro short lifespan Difficulty in getting healthy cells in diseased organs |

| Adult stem cells (ASCs) | No tissue rejection No ethical problems No tumors Easy isolation In some cases easy access (e.g. apheresis and subcutaneous fat) |

Low number in each tissue Difficult in vitro expansion without differentiation |

| Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) | Unlimited ability to self-renew Potential to differentiate into many specialized cells from all the three germ layers |

Ethical and political problems Tumorigenity Need for feeder cell layers (risk of xeno-contamination when mouse fibroblasts are used) |

| Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) | Similar as ESCs Easier generation than ESCs No ethical problems |

Tumorigenity |

| Amniotic fluid-derived stem cells (AFSCs) | Great ability to proliferate without feeder cells No tumorigenic No ethical problems Possibility of preservation as lifelong autologous stem cells together with other perinatal stem cells (umbilical cord placenta and amnion membrane-derived stem cells) Possibility of ante-natal collection by amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling |

Further research is needed (being the latest discovery) |

2.2. Biomaterials

Tissues generally consist of cells and extracellular matrix (ECM). Biomaterials usually serve as ECM, giving both structural and functional support. During the last few years, ECM has been shown to play a key role in many different functions, such as gene expression, survival, death, proliferation, migration, differentiation. Therefore, all of them should be reproduced by biomaterials enriched with bioactive factors, such as growth factors and cytokines. The materials used in RM (Table 5) can be classified as natural or synthetic with different advantages and disadvantages.

Table 5.

Examples of biomaterials used in RM.

| Origin | Examples |

|---|---|

| Natural materials | Collagen, fibrin, chitosan, dextran, alginate, gelatin, cellulose, hyaluronic acid (HA), silk fibroin |

| Acellular tissue matrix | Bladder acellular matrix (BAM), small intestinal submucosa (SIS), bowel acellular tissue matrix (ATM), bovine pericardium (BPV), human placental membrane (HPM) |

| Synthetic polymers | Polyglycolic acid (PGA), polylactic acid (PLA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), poly(copralactone-co-ethyl ethylene posphate) (PCLEEP), polydioxane (PDS), polyethylene glycol (PGE), poly-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)metacrylamide (PHEMA), poly-N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (PHPMA) |

Synthetic materials can be identically reproduced on a large scale with specific properties of microstructure and degradation rate. However, they have the important drawback of lacking of biologic recognition. Nevertheless, different research groups are trying to solve this problem by incorporating the molecules to help the recognition of synthetic scaffolds. By assembling electrospun nanofibers and self-assembling peptides with functional motifs (Fig. 3), Gelain et al. created neural prosthetics which had shown to lead nerve regeneration in rats with chronic spinal cord injury [40].

Fig. 3.

Schematic models of the self-assembling peptide used by Gelain et al., RADA16 (blue bars), extended though several different functional motifs (different colored bars) in order to design different peptides. A schematic model of a self-assembling nanofiber scaffold with combinatorial motifs carrying different biological functions is shown right.

Source: Gelain F, Bottai D, Vescovi A, Zhang S. Designer Self-Assembling Peptide Nanofiber Scaffolds for Adult Mouse Neural Stem Cell 3-Dimensional Cultures. PLoS One. 2006 Dec 27;1:e119

On the other hand, natural materials can be integrated perfectly. They can be furnished by other living organisms, but in these cases they present cellular components which may induce an immune response. The latter can be avoided by making use of detergents (e.g. trypsin/TritonX-100) which leave only ECM, creating the so-called acellular tissue matrices [41]. Unlike synthetic ones, both naturally derived materials and acellular tissue matrices can not be produced easily in large quantities according to good manufacturing practice.

The most used natural biomaterial is probably the hyaluronic acid, which is a common anti-aging product in skin-care products and injectable facial fillers. As for sample acellular tissue matrix applications, Portis et al. demonstrated the feasibility of laparoscopic bladder augmentation in minipigs using porcine bowel acellular tissue matrix and porcine small intestinal submucosa [42].

The ideal biomaterial should be biocompatible and biodegradable at the same rate as regeneration process without leaving toxic end-products, interfering with regeneration process and causing inflammation and/or obstruction [43].

Another important feature is porosity, which allows the exchange of nutrients and wastes. This property is extremely difficult to be achieved successfully and 3D bioprinters seem to be the perfect solution of this problem. The research group guided by Shaochen Chen bioprinted a 3-D liver-like device to detoxify blood, by encapsulating functional nanoparticles in a biocompatible hydrogel [44]. Thanks to a technology, called dynamic optical projection stereolithography, complex 3D microstructures, like blood vessels, can be printed within few seconds. Without vasculature printing, essential for distributing nutrients and oxygen, tissue-engineered organs, such as liver or kidney, are useless in clinical practice. The biofabrication technique grounds on a photo-induced solidification process, which uses soft biocompatible hydrogels containing living cells and forms one layer of solid structure at a time, but in a continuous fashion, by shining light on a selected area of a solution containing photo-sensitive biopolymers and cells [45]. Other current 3D biofabrication techniques, such as two-photon photopolymerization, can take hours to fabricate a 3D part. At last, Organovo is a medical start-up intending to deliver bioprinted organs, like liver, for surgical therapy and transplantation [46].

2.3. Implantation of scaffolds seeded with cells

This approach is a combination of the previous two strategies.

In 2006, Atala et al. reported autologous engineered bladder constructs could be used in patients suffering from myelomeningocele needing augmentation cystoplasty [20]. The synthetic scaffold was made up of collagen and PGA and seeded with patient's urothelial and smooth muscle cells, respectively on the endoluminal and abluminal side. These cells were obtained through a patient's biopsy and expanded in vitro before scaffold seeding.

Another example is the realization of a bioartificial liver obtained through the decellularization process [23]. The latter consists of eliminating all liver cells preserving the structural and functional characteristics of the vascular network, which allows the organ perfusion. Later, adult hepatocytes recolonize liver matrix and support physiological functions, like albumin excretion and urea synthesis. The liver grafts obtained in this way were successfully transplanted into mice, paving the way for a new approach to the treatment of end-stage liver diseases.

3. Conclusions

RM opened new avenues for curing patients with difficult-to-treat diseases and physically impaired tissues. Despite many successes, RM is still unfamiliar to many scientists and clinicians. This poses a great limit, as tissue engineering and regenerative medicine could overcome the unsolvable problems of the current medical treatments.

In order to resort to RM in the clinical setting on a daily basis, it is mandatory to obtain important financial investments from different sources including governments and industries that are oriented toward research and medical innovation. There is a considerable need for long-term vision and support for RM to accelerate the development of novel therapies and to promote the stability of collaborations around the world.

In addition to the financial and technical concerns, process development is a significant hurdle to manage with and it includes intellectual property, manufacturing, and logistical concerns. Cell therapy and tissue engineering have the potential to revolutionize patients’ care. But in order to materialize this concept, ideas generated in the laboratory need to be taken through process development and transformed into widespread commercial products. Licensing, legal support, logistics, supervision at the governmental level, unexpected failures, and team management play a pivotal role.

Since RM is a cross-sectional area of research, a multidisciplinary team, including doctors, biologists, bioengineers, chemists, and surgeons, is required to initiate and master the key steps involved in cell therapy and tissue engineering. This necessitates the need for training courses of cell culture, stem cell technology, tissue engineering and experimental surgery.

The crucial point of this revolution is transforming the current numerous scientific discoveries into novel and viable therapies: from bench to bedside.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- [1].Mason C, Dunnill P. A brief definition of regenerative medicine. Regen Med. 2008;3(1):1–5. doi: 10.2217/17460751.3.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fahy GM. Dr. William Haseltine on regenerative medicine, aging and human immortality. Life Ext. 2002 Jul 07;8:58. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kaiser LR. The future of multihospital systems. Top Health Care Financ. 1992;18(4):32–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Aida L. Alexis Carrel (1873–1944): visionary vascular surgeon and pioneer in organ transplantation. J Med Biogr. 2014 Aug 03;22:172–5. doi: 10.1177/0967772013516899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kragl M, Knapp D, Nacu E, Khattak S, Maden M, Epperlein HH, et al. Cells keep a memory of their tissue origin during axolotl limb regeneration. Nature. 2009;460:60–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Illingworth CM. Trapped fingers and amputated finger tips in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1974 Dec 06;9:853–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(74)80220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nelson TJ, Behfar A, Terzic A. Strategies for therapeutic repair: the R3 regenerative medicine paradigm. Clin Transl Sci. 2008;1:168–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vanderhoof JA, Matya SM. Enteral and parenteral nutrition in patients with short-bowel syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999 Aug 04;9:214–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1072247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Duel BP, Gonzalez R, Barthold JS. Alternative techniques for augmentation cystoplasty. J Urol. 1998;159(3):998–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guild WR, Harrison JH, Merrill JP, Murray J. Successful homotransplantation of the kidney in an identical twin. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1955;67:167–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Starzl TE. History of clinical transplantation. World J Surg. 2000 Jul 07;24:759–82. doi: 10.1007/s002680010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Saidi RF, Hejazii Kenari SK. Clinical transplantation and tolerance: are we there yet? Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2014;5(4):137–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schold J, Srinivas TR, Sehgal AR, Meier-Kriesche HU. Half of kidney transplant candidates who are older than 60 years now placed on the waiting list will die before receiving a deceased-donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Jul 07;4:1239–45. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01280209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].The 2012 OASDI Trustees Report. Table IV.B2 [Google Scholar]

- [15].Prindull G, Prindull B, Meulen N. Haematopoietic stem cells (CFUc) in human cord blood. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1978 Jul 04;67:413–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1978.tb16347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981 Jul;292(5819):154–6. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Burke JF, Yannas IV, Quinby WC, Jr, Bondoc CC, Jung WK. Successful use of a physiologically acceptable artificial skin in the treatment of extensive burn injury. Ann Surg. 1981 Oct 04;194:413–28. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198110000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Campbell KH1, McWhir J, Ritchie WA, Wilmut I. Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line. Nature. 1996 Mar;380(6569):64–6. doi: 10.1038/380064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998 Nov;282(5391):1145–7. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Atala A, Bauer SB, Soker S, Yoo JJ, Retik AB. Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1241–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Raya-Rivera A, Esquiliano DR, Yoo JJ, Lopez-Bayghen E, Soker S, Atala A. Tissue-engineered autologous urethras for patients who need reconstruction: an observational study. Lancet. 2011 Apr;377(9772):1175–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62354-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].De Coppi P, Bartsch G, Jr, Siddiqui MM, Xu T, Santos CC, Perin L, et al. Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(1):100–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Uygun BE, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yagi H, Izamis ML, Guzzardi MA, Shulman C, et al. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nat Med. 2010 Jul 07;16:814–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Atala A. Regenerative medicine strategies. J Pediatr Surg. 2012 Jan 01;47:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ilic D, Polak JM. Stem cells in regenerative medicine: introduction. Br Med Bull. 2011;98:117–26. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Barrilleaux B, Phinney DG, Prockop DJ, O’Connor KC. Review: ex vivo engineering of living tissues with adult stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2006 Nov 11;12:3007–19. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pacini S. Deterministic and stochastic approaches in the clinical application of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) Front Cell Dev Biol. 2014 Sep 02;12:50. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2014.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Brivanlou AH, Gage FH, Jaenisch R, Jessell T, Melton D, Rossant J. Stem cells. Setting standards for human embryonic stem cells. Science. 2003;300(5621):913–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1082940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Unger C, Skottman H, Blomberg P, Dilber MS, Hovatta O. Good manufacturing practice and clinical-grade human embryonic stem cell lines. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(R1):48–53. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ben-David U, Benvenisty N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(4):268–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/stem-cells-were-gods-will-says-first-recipient-of-treatment/2011/04/14/AFxgKIjD story.html .

- [32].Hochedlinger K, Rideout WM, Kyba M, Daley GQ, Blelloch R, Jaenisch R. Nuclear transplantation, embryonic stem cells and the potentialfor cell therapy. Hematol J. 2004;5(Suppl. 3):114–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(1):101–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhou W, Freed CR. Adenoviral gene delivery can reprogram human fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(11):2667–74. doi: 10.1002/stem.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Abad M, Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, Cañamero M, Rayon T, Ors I, et al. Reprogramming in vivo produces teratomas and iPS cells withtotipotency features. Nature. 2013 Oct;502(7471):340–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jang J, Yoo JE, Lee JA, Lee DR, Kim JY, Huh YJ, et al. Diseasespecific induced pluripotent stem cells: a platform for human disease modeling and drug discovery. Exp Mol Med. 2012 Mar 03;44:202–13. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.3.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. http://www.cdb.riken.jp/en/news/2014/news not/researchs/09153047.html .

- [39].Schmidt D, Achermann J, Odermatt B, Genoni M, Zund G, Hoerstrup SP. Cryopreserved amniotic fluid-derived cells: a lifelong autologous fetal stem cell source for heart valve tissue engineering. J Heart Valve Dis. 2008 Jul 04;17:446–55. discussion 455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gelain F, Panseri S, Antonini S, Cunha C, Donega M, Lowery J, et al. Transplantation of nanostructured composite scaffolds results in the regeneration of chronically injured spinal cords. ACS Nano. 2011 Jan 01;5:227–36. doi: 10.1021/nn102461w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Arenas-Herrera JE, Ko IK, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Decellularization for whole organ bioengineering. Biomed Mater. 2013 Feb 01;8:014106. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/8/1/014106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Reing JE, Brown BN, Daly KA, Freund JM, Gilbert TW, Hsiong SX, et al. The effects of processing methods upon mechanical and biologic properties of porcine dermal extracellular matrix scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2010;31(33):8626–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gilbert TW, Stewart-Akers AM, Badylak SF. A quantitative method for evaluating the degradation of biologic scaffold materials. Biomaterials. 2007;28(2):147–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gou M, Qu X, Zhu W, Xiang M, Yang J, Zhang K, et al. Bio-inspired detoxification using 3D-printed hydrogel nanocomposites. Nat Commun. 2014;5(May):3774. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang AP, Qu X, Soman P, Hribar KC, Lee JW, Chen S, et al. Rapid fabrication of complex 3D extracellular microenvironments by dynamic optical projection stereolithography. Adv Mater. 2012 Aug 31;24:4266–70. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. www.organovo.com .