Abstract

Objectives

Gout care remains highly suboptimal, contributing to an increased global disease burden. To understand barriers to gout care, our aim was to provide a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies worldwide reporting provider and patient perspectives and experiences with management.

Methods

We conducted a mapped search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Social Sciences Citation Index databases and selected qualitative studies of provider and patient perspectives on gout management. We used thematic synthesis to combine the included studies and identify key themes across studies.

Results

We included 20 studies that reported the experiences and perspectives of 480 gout patients and 120 providers spanning five different countries across three continents. We identified three predominant provider themes: knowledge gaps and management approaches; perceptions and beliefs about gout patients; and system barriers to optimal gout care (e.g. time constraints and a lack of incentives). We also identified four predominant themes among gout patients: limited gout knowledge; interactions with health-care providers; attitudes towards and experiences with taking medication; and practical barriers to long-term medication use.

Conclusion

Our systematic review of worldwide literature consistently identified gaps in gout knowledge among providers, which is likely to contribute to patients’ lack of appropriate education about the fundamental causes of and essential treatment approaches for gout. Furthermore, system barriers among providers and day-to-day challenges of taking long-term medications among patients are considerable. These factors provide key targets to improve the widespread suboptimal gout care.

Keywords: gout, urate-lowering therapy, attitudes to health, qualitative research, quality of care

Rheumatology key messages

Worldwide literature consistently identified gaps in gout knowledge among providers.

Provider knowledge gaps are likely to contribute to patients’ lack of education about the causes of and treatments approaches for gout.

System barriers among providers and day-to-day challenges of taking long-term medications among gout patients are considerable.

Introduction

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis worldwide [1–3]. Unlike other arthritides, the pathogenesis of gout is well understood, including the causal role of serum uric acid (SUA) [4]. Despite the availability of urate-lowering therapy (ULT), gout care remains remarkably suboptimal, and the majority of gout patients continue to experience acute attacks and remain at risk for disease progression [5]. Indeed, a recent study highlighted that up to 89% of hospitalizations with a principal discharge diagnosis of gout were preventable, owing to inadequate care [6]. Although the majority of gout patients are indicated for ULT according to rheumatology guidelines, only a small proportion receive treatment [7, 8]. Moreover, many patients are often prescribed ULT at a single insufficient fixed dose, and are thus often undertreated according to rheumatology guidelines [9, 10]. Furthermore, few patients receive clear education about the curable nature of the disease or personalized lifestyle advice to reduce risk factors and co-morbidities [11–15]. As a consequence, only a minority become free of gout, thereby further contributing to an increasing disease burden [9, 10, 16, 17]. Despite this widely reported suboptimal gout care, relatively limited research has sought to improve management among this patient population.

To that effect, an in-depth understanding of provider and patient perspectives on and experiences with barriers to the delivery of optimal gout care is crucial to inform the development of evidence-based interventions to improve disease management and patient outcomes effectively. Thus, we systematically reviewed and thematically synthesized the qualitative literature to date reporting gout patient and provider perspectives on gout management.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We conducted a search of MEDLINE (1946–2016), EMBASE (1974–2016), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (1982–2016) and Social Sciences Citation Index (1965–2016) databases. Our search strategy used mapped subject headings together with keywords (expressed as truncated wildcards where possible [18]) for unindexed terms relating to the concepts of gout care and qualitative research (see supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). Inclusion criteria were as follows: a study sample of gout patients or their providers; studies describing these individuals’ views on gout management; qualitative study design (e.g. semi-structured interviews, focus groups); primary research article; and English language of publication.

Study selection

We reviewed titles and abstracts for inclusion of studies meeting our eligibility criteria. Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of citations identified from the literature searches. Abstracts meeting all inclusion criteria were forwarded for full-text review. The same two authors assessed the selected full-text articles for inclusion on the basis of the aforementioned eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We also searched for unindexed articles through expert consultation and a hand search of relevant bibliographies.

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted the following information from included studies: year of publication; country; participant characteristics; and data collection and analysis methods. We conducted a thematic synthesis, which combines approaches from both meta-ethnography and grounded theory and was originally developed to guide reviews of intervention needs, appropriateness and effectiveness [19]. Thematic synthesis is composed of three steps: line-by-line coding of the findings from primary studies; organization of codes into descriptive themes; and generation of analytical themes [20]. Accordingly, the findings of each article (including text, tables and any available supplementary material, available at Rheumatology online) were imported verbatim into NVivo, a computer software package for the analysis of qualitative data [19]. Two authors independently read and annotated the data and, after discussion, agreed on an initial coding framework. Each article was re-read to ensure that all concepts had been captured. These concepts were organized into descriptive themes, and we explored the relationships between these descriptive themes further to develop higher-order analytical themes.

Patient collaboration

We collaborated with the Arthritis Patient Advisory Board of Arthritis Research Canada, an established consumer group that regularly collaborates in arthritis research [21]. Arthritis Patient Advisory Board members were engaged throughout the present study, including research question development, study design, and analysis and interpretation of the results.

Results

Literature search results

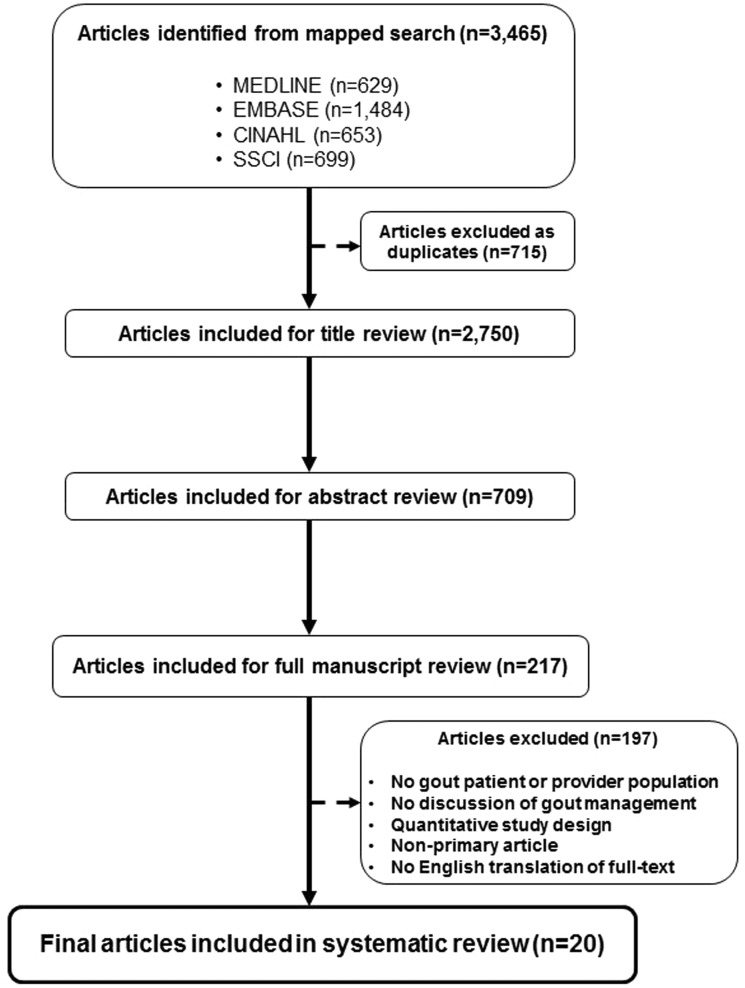

Our search strategy retrieved 2750 articles after the removal of duplicates (Fig. 1). After title and abstract review, studies were excluded for any of the following reasons: no gout patient or provider population; no discussion of gout management; quantitative study design; non-primary article (e.g. reviews, editorials); and non-English language of publication. Two hundred and seventeen studies were forwarded for full-text review and data abstraction. Twenty studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in our systematic review.

Fig. 1.

Systematic review study flow

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 20 studies included in the systematic review are summarized in Table 1. We identified studies from several geographical settings worldwide, namely the USA (n = 5), the UK (n = 5), New Zealand (n = 5), Australia (n = 3) and the Netherlands (n = 2). Qualitative interviews were conducted in 16 studies, while 3 used the nominal group technique and 1 study conducted focus groups. Although nearly all included studies reported patient perspectives (n = 16 of 20) for a total of 480 patients, only seven studies reported provider perspectives (n = 120 providers). Among those investigating provider perspectives, three focused exclusively on general practitioners (GPs), and four studies contained mixed provider populations, additionally including rheumatologists, nurses and pharmacists.

Table 1.

Characteristics of qualitative studies included in systematic review

| References | Year | Country | Sample size | Sexa, male, % | Age, yearsa | Data collection | Conceptual methodological framework | Data analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Providers | ||||||||

| Katz & Weiner [22] | 1975 | USA | 16 | – | 100 | Mean, 44 | Interviews | – | – |

| Harrold et al. [23] | 2010 | USA | 26 | 15 | 77 | Mean, 73 | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Lindsay et al. [14] | 2011 | New Zealand | 11 | – | 100 | Median, 46 | Interviews | Grounded theory | Grounded theory analysis |

| Martini et al. [24] | 2012 | New Zealand | 60 | – | 90 | Mean, 61 | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Spencer et al. [13] | 2012 | UK | 20 | 18 | 75 | Mean, 61 | Interviews | Grounded theory | Grounded theory analysis |

| Te Karu et al. [15] | 2013 | New Zealand | 12 | – | 67 | Range, 48–79 | Interviews | Kaupapa Maori approach | Thematic analysis |

| Singh [25] | 2014 | USA | 43 | – | 67 | Mean, 64 | Nominal groups | Nominal groups | Content analysis |

| Singh [26] | 2014 | USA | 17 | – | 47 | Mean, 65 | Nominal groups | Nominal groups | Content analysis |

| Singh [27] | 2014 | USA | 62 | – | 60 | Mean, 65 | Nominal groups | Nominal groups | Content analysis |

| Hmar et al. [28] | 2015 | Australia | – | 12 | – | – | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Liddle et al. [29] | 2015 | UK | 43 | – | 67 | Range, 32–87 | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Richardson et al. [30] | 2015 | UK | 43 | – | 0 | Range, 32–82 | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| van Onna et al. [31] | 2015 | The Netherlands | 15 | – | 93 | Mean, 63 | Interviews | Grounded theory | Grounded theory analysis |

| Chandratre et al. [32] | 2016 | UK | 17 | – | 88 | Mean, 71 | Focus groups | – | Thematic analysis |

| Humphrey et al. [33] | 2016 | New Zealand | – | 14 | – | – | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Jeyaruban et al. [34] | 2016 | Australia | – | 14 | – | – | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Rebello et al. [35] | 2016 | New Zealand | 30 | – | 80 | Range, 28–76 | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Richardson et al. [36] | 2016 | UK | 43 | – | 67 | Range, 30–89 | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

| Spaetgens et al. [37] | 2016 | The Netherlands | – | 32 | – | – | Interviews | Grounded theory | Grounded theory analysis |

| Vaccher et al. [38] | 2016 | Australia | 22 | 15 | 86 | Median, 59 | Interviews | – | Thematic analysis |

Refers to patient sample.

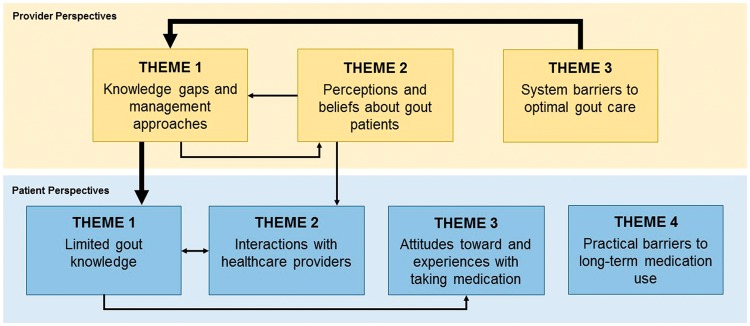

Synthesis of qualitative studies

Our thematic analyses identified three predominant, overlapping and interlocking analytical themes among providers: knowledge gaps and management approaches, perceptions and beliefs about gout patients, and system barriers to optimal gout care. We also identified four predominant themes among gout patients: limited gout knowledge; interactions with health-care providers; attitudes towards and experiences with taking medication; and practical barriers to long-term medication use. Where possible, available quotations corresponding to the identified themes are shown in Tables 2 and 3, and the relationship between analytical themes is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Illustrative provider quotations

| Analytical theme/subtheme | Quotations | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge gaps and management approaches | ||

| Training in gout care | ‘I think that there is lack of knowledge by both patients and health professionals. I just thought you just had gout flare ups and then it just went away, so there is definitely a need for education and better training.’ | [13] |

| Gout guidelines | ‘I think I would usually just make that decision from my clinical experience and would tailor that to my patient’s needs. I don’t tend to use clinical guidelines for gout. I wasn’t aware that any existed.’ | [13] |

| ‘I’m sure they exist. … I haven’t actually personally, ah, looked at anything that’s called gout guidelines.’ | [38] | |

| Treating gout as an acute condition | ‘Even in my own mind I don’t treat gout as a chronic disease, I just tend to deal with the acute event, so I am just as guilty in not always offering preventative options or giving that information, because perhaps a 50-year-old may not have another attack for 10 years.’ | [13] |

| Acute gout care | ‘If it’s mild or moderate non-steroidal to settle the initial gout. If it’s severe then might use steroids like prednisolone.’ | [34] |

| Chronic gout care: initiating ULT | ‘I’d be wanting to put them on [allopurinol] if they’re having attacks every month or so.’ | [38] |

| ‘The main reason to start with UALT is when patients have more than three gout attacks per year.’ | [37] | |

| Chronic gout care: prophylaxis | ‘I combine allopurinol and colchicine to prevent acute gout flares, for a period of 2–4 weeks.’ | [37] |

| ‘I do not prescribe prophylactic treatment, I advise patients to drink more and sometimes stop diuretics.’ | [37] | |

| Chronic gout care: monitoring response to ULT | ‘Because you can have gout with a normal uric acid level so therefore, you know, it isn’t actually an effective monitoring agent and I’m not sure what effect allopurinol has on the level of uric acid anyway.’ | [28] |

| ‘The target level of 0.36 mmol/l is not a strict treatment goal. I accept higher serum uric acid levels if the number of acute attacks is decreased.’ | [37] | |

| Perceptions and beliefs about gout patients | ||

| Taking medications: viewing patients as adherent | ‘Adherence to uric acid-lowering therapy is not a problem in patients with gout, since they are well aware of the fact they will get new gout attacks if they do not take their medication.’ | [37] |

| Taking medications: viewing patients as non-adherent | ‘I think patients with gout take their medication (uric acid-lowering therapy) very well in the beginning, but in the course of time become less adherent. Then these patients will return with a gout flare.’ | [37] |

| ‘When patients have had long intervals without any attacks, they probably think they can get by without the medication … so they don’t understand that this is a long-term therapy.’ | [28] | |

| Adhering to lifestyle advice | ‘[Lifestyle changes] good at the beginning and then they get complacent and fall off the wagon and they tend not to care about diet afterwards.’ | [34] |

| Feeling frustrated when treating patients | ‘At the end of the day, you can only do so much with medication. What do they say, you can take a horse to the water, you can’t make him drink it.’ | [33] |

| Gout patient education | ‘Before they come in [they do] not very good knowledge despite being on high doses of allopurinol.’ | [34] |

| ‘I should give them handouts probably, so they’ve got more education.’ | [38] | |

| System barriers to optimal gout care | ||

| Time constraints in clinical practice | ‘It’s another thing, too, the time issue. ’Cause if you’re really, really busy, you don’t spend time to talk to the patient, you don’t have time, if we’re busy.’ | [33] |

| Incentives to optimize care | ‘With any GP unless there is some sort of financial incentive, say, for surgeries to test the uric acid levels of gout patients on a regular basis, I’m not sure that would be done. That would only change if some guidelines came out that suggested that it would be best practice to do so.’ | [13] |

| Language and literacy barriers | “You can never perceive the level of comprehension. It’s very hard, you know, people will go to them ‘Do you understand?’ and they’ll go [nods head] and mean ‘no’.” | [33] |

GP: general practitioner; SUA: serum uric acid; UALT: uric acid-lowering therapy; ULT: urate-lowering therapy.

Table 3.

Illustrative patient quotations

| Analytical theme/subtheme | Quotations | |

|---|---|---|

| Limited gout knowledge | ||

| Gout as a chronic or progressive condition | ‘Don’t realize when you get it, the effect that its having on you, and I had some quite severe attacks in my hands as well as my feet, and that’s left me now with permanent damage, which I didn’t realise was going to happen.’ | [36] |

| Cause and curable nature of gout | ‘I mean, I just thought I had arthritis and had to put up with the pain in my joints that have developed over the last seven years. I didn’t realise that, if you could get the uric acid levels down in your blood, you could try and prevent gout attacks from happening.’ | [13] |

| Availability of curative medications | ‘First time I heard there was a pill to prevent gout. I wish I had known before. … I’m so proud; pleased to know there is a pill to prevent gout.’ | [15] |

| ‘I think I have accepted the fact that there is no cure. It is up to me just to minimize it, I think. I don’t think there is any cure because I haven’t talked to anybody who has had it and say they don’t get it anymore. Is that possible?’ | [14] | |

| How to take medications | ‘I took the allopurinol for some time [a couple of years] and didn’t have any attacks, so I thought I had cracked it. I thought it had gone so I took myself off the allopurinol and I thought I would be fine.’ | [13] |

| ‘Allopurinol is a pain medication.’ | [24] | |

| Experiencing paradoxical mobilization flares | “I had heard from someone … they say, ‘oh when you take allopurinol boy it gives you the gout’, and I was like ‘aye, I won’t take it.’ I did get some years ago and I put them up in the top of the cupboard and I wouldn’t take them.” | [15] |

| ‘The one big toe had no signs of pain or anything else up until I took the medicine. … I’m glad to get rid of this [allopurinol] because it didn’t help. It caused a problem.’ | [23] | |

| Interactions with health-care providers | ||

| Receiving insufficient information from providers | ‘I don’t think they gave you enough. It kind of wasn’t even the basics. There were no follow-ups or anything and I was going regularly. There must have been time in there. I didn’t know about uric acid levels or what I should aim for. In my mind, I never had it explained.’ | [15] |

| ‘We’ve all got ignorance of it. Doctors don’t sort of explain exactly what it is.’ | [32] | |

| Information needs: medication information | ‘I need to know what each medication is supposed to do and how and when to take it.’ | [26] |

| ‘I’d like to know the side effects though, properly [yeah] from a doctor, and not from the internet.’ | [32] | |

| Information needs: dietary triggers | ‘…they said what not to eat on the book … on the sheet said I can eat it … so it was confusing. … Feel annoyed like I had no idea.’ | [35] |

| ‘It’s just a great muddle about when it comes to food.’ | [32] | |

| Seeking information online | ‘I've looked up online information relating to gout and the causes of it. And I think for as many articles that are written there's a different identifier and you know if I were to—I just get the impression that if I were to follow all the advice that’s in all the articles that I've read, I wouldn't eat or drink anything ever again because there just seems to be such a wide array of possible causes.’ | [29]a |

| Relationship with provider: feeling dismissed | ‘But you couldn’t talk to my doctor about it, he wasn’t interested.’ | [32] |

| ‘I sometimes wonder why the heck I even go to the doctors … he just wants to get rid of you.’ | [23] | |

| Relationship with provider: feeling judged | ‘No, you go in, you go in, you’re the doctor, how much do you drink? I said I don’t drink doctor. But as I say it’s still treated as a bit of a thing, you know. I think doctors do actually. You know, you’ve been drinking. How much do you drink?’ | [32] |

| ‘I didn’t bother going to the doctors. At one time when I was a lot younger I was embarrassed to tell someone that I had gout because you would get the sarcasm.’ | [13] | |

| Attitudes towards and experiences with taking medication | ||

| Feeling reluctant to take long-term medications | ‘It was against all of my personal philosophies to spend the rest of my life taking a pill.’ | [38] |

| ‘…Besides, I don’t like the idea of taking medication constantly.’ | [22] | |

| ‘I find mine just goes quickly, so I’m tremendously happy, I wouldn’t want to be on long-term allopurinol, not because there’s anything wrong with it, or anything, or anything else; I’m very, very content with what I’ve got.’ | [32] | |

| Having concerns about medication side effects or interactions | ‘I worry about the long-term effects the drugs have on my health.’ | [27] |

| Experiencing side effects | ‘I took allopurinol later in the day without food; stomach starting feeling bad.’ | [25] |

| Using alternative therapies | ‘I take it because it’s herbal … there’s no chemicals in the herbal tablets.’ | [35] |

| ‘I read cherry juice was good, so I took cherry juice instead of allopurinol.’ | [25] | |

| Motivators to take medication | ‘If I do not take my tablets, well, I am afraid that I will get another gout attack. I absolutely do not want that. I was unable to work during an attack, and yes … you lose money, when you are unable to work.’ | [31] |

| ‘Well I’m still eating mussels and king prawns and everything like that. The allopurinol I suppose is to let you do that isn’t it.’ | [32] | |

| ‘I have been shot—I’d rather be shot again than have the pain due to gout.’ | [25] | |

| Acceptance of needing medication | “The prospect of, ‘I’ve got to take this for the rest’, you know, ‘the rest of my life’, is … it was difficult to adjust to.” | [29]a |

| “…It does take a period of adjustment to actually, you know, ‘I’m going to be doing this for the rest of my life’, rather than, ‘I’ve got something in the background which flares up occasionally.” | [31] | |

| Practical barriers to long-term medication use | ||

| Insurance coverage/affordability | ‘Uloric worked fine with the gout flares, but due to my insurance the medication was expensive.’ | [25] |

| Forgetting to take medications | ‘I’m frequently forgetful.’ | [22] |

| Taking too many medications | ‘I have so much on my mind due to the all the pills I have to take.’ | [25] |

| Travelling | ‘Sometimes I am out of town, and did not have my medication with me.’ | [25] |

| Support strategies | ‘I have been using it [pill organizer] for years, that’s the one thing that helped, that nailed it.’ | [25] |

| ‘It is just routine. I know that when I eat my slice of bread in the morning, I also have to take those two tablets.’ | [31] | |

Quote taken from supplementary material.

Fig. 2.

Thematic schema representing the relationships between provider (yellow) and patient (blue) barriers to gout management

Major barriers are represented by bold lines.

Provider perspectives

Knowledge gaps and management approaches

Some providers felt insufficiently trained to provide gout care and education and felt there was a need for improved or continuing medical education [13, 23, 28, 38]. Many were not aware of or did follow any gout management guidelines [13, 28, 34, 38]. Gout was sometimes treated as an acute condition rather than a chronic disease [33]; treatment of acute gout was considered satisfying, as most patients would respond to treatment [23], and providers assumed that patients preferred this approach to taking long-term medication [13]. To treat acute gout attacks, physicians reported prescribing NSAIDs, colchicine or CSs [23, 34, 38]. Attack frequency was cited as the main reason for prescribing ULT [13, 23, 28, 38, 37]. Very few GPs mentioned tophi as an indication for ULT [37]. Allopurinol was the most commonly prescribed (i.e. first-line) ULT [13, 23, 38, 34], and starting doses ranged from 50 to 300 mg [23, 34, 38]. Although this was sometimes adjusted based on SUA level, clinical symptoms and renal function [23, 28, 34], only half of the GPs in one study reported up-titrating allopurinol [38]; moreover, non-rheumatologists hesitated to exceed a dose of 300 mg [13, 28]. Anti-inflammatory medication was sometimes prescribed alongside initial ULT [23, 28, –38, 33, 37], although others did not add this prophylactic treatment [38, 37]. The effectiveness of ULT was determined according to various factors, including a decrease in SUA level [23, 28, 33, 34, 37], abatement of attacks [23, 28, 34, 37] and, rarely, by the resolution of tophi [37]. The target SUA level was not viewed as a strict treatment goal by many, leading providers to accept higher SUA in the absence of new attacks [37], whereas others were altogether unaware of the target level [37].

Perceptions and beliefs about gout patients

Providers held varying, even opposing, perceptions and beliefs about their gout patients, particularly surrounding their adherence to ULT. Many believed that gout patients were adherent to gout medications and aware of the consequences of not taking these medications (e.g. experiencing new attacks) [23, 34, 37]. Conversely, other providers (including rheumatologists) recognized that non-adherence to gout therapies posed a challenge in gout care [13, 28, 33, 37, 38]. Specifically, some felt that their patients took their medication in the beginning, but over time became less adherent [28, 37], potentially owing to a lack of understanding about the chronic nature of gout therapy [28]. Similar attitudes were held concerning adherence to lifestyle changes, namely diet [34]. Some providers felt that patient non-adherence left them no other option but to prescribe medications repeatedly to treat acute attacks [13], and a sense of frustration and futility was sometimes expressed surrounding gout care [33]. Therefore, patient education was considered vital to successful gout management [23], although upon reflection many thought that patients did not have sufficient knowledge or education about gout [13, 28, 34, 38], which they felt contributed to poor adherence [28]. Meanwhile, others believed that their patients had an understanding about the cause of gout and need for long-term medication [13, 23].

System barriers to optimal gout care

Time constraints were regarded as a major barrier to optimal gout management [23, 33, 37]. Providers (namely GPs) felt they did not have sufficient time to offer appropriate gout education to their patients [23, 33]. In one study, a financial incentive was proposed to optimize long-term gout care, and providers felt that they would be unlikely to alter their current standard of care otherwise [13]. Finally, language and cultural factors were cited as added barriers to gout care, which was complicated by the limited time available to spend with each patient [33].

Patient perspectives

Limited gout knowledge

All studies reported a suboptimal understanding of gout and its treatment among patients. Gout was not considered a chronic or progressive condition requiring long-term management; instead, patients reported treating their gout as episodic and were not aware of the potentially progressive features of the disease (e.g. tophi development, joint damage) [13, 14, 23, 24, 29, 31, 32, 36]. Many patients were not aware of the cause of gout (i.e. the causal role of SUA); alternative proposed causes of gout included gout sugars [31], joint injury [15], ageing [13, 14, 32], salty food leading to an accumulation of salt [24], and an imbalance of acid and alkali in the body [31]. Patients did not know that gout could be controlled with medications to lower SUA, and instead believed that they would have to adjust to living with the pain caused by the disease [13–15, 23]. Patients were pleased to learn that there was medication, such as allopurinol, available to treat their gout and wished that they had known this sooner [15, 38, 32]. Nevertheless, some felt unsure about how to take the various medication (e.g. do we take or not take allopurinol during a gout attack?) or how long to take it for [13, 22–26, 38]. Moreover, when taking ULT, these patients sometimes experienced paradoxical attacks without prior explanation or warning from their provider; these patients subsequently stopped taking their ULT, believing that the medication was making their gout worse [13, 15, 23, 25, 31, 32, 36].

Interactions with health-care providers

Patients described a variety of experiences and interactions with providers when receiving care for their gout. Many felt that they were not receiving sufficient or necessary gout education and information from their doctor [15, 23, 29, 32, 35, 36, 38]. Patients wanted more information about the cause of gout [29, 31, 36, 38], dietary triggers [24, 27, 29, 32, 35], and the proper use, side effects and purpose of medications [15, 23, 29, 31, 32, 36]. Patients searched for gout information on their own, which sometimes provided frightening, confusing or ambiguous information [27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 38]. Some questioned the credibility of this information obtained from the internet [32, 31]. Some felt altogether dismissed by their providers [15, 23, 29, 32, 36], whereas others felt that their provider considered gout to be comical or self-inflicted (such as with regard to alcohol consumption) [13, 32].

Attitudes towards and experiences with taking medication

Many patients expressed reluctance to take long-term medication to manage their gout. For some, this came from a general preference to avoid using medications [22, 24, 27, 32, 35, 36, 38]. Others had specific concerns, such as possible long-term or cumulative side effects or interactions with other medications [13, 22, 23, 25–27, 32]. Indeed, some individuals reported experiencing various side effects from their gout medications, including nausea, gastrointestinal effects, renal complications and rashes, which led to stopping the medication [15, 24–27, 35, 38]. Some patients opted to try alternative therapies, such as cherry juice or herbal supplements [15, 23–25, 35, 38]. Nevertheless, a variety of factors still served to motivate gout patients to take ULT, including the desire to avoid further painful attacks and prevent progression and disability [23, 25, 31, 32, 36]. Others were motivated by their need to maintain employment [31], desire to resume prior activities and hobbies [25, 36], and ability to eat foods that would have otherwise triggered a gout attack [25, 32]. The decision to take medication for gout was sometimes described as an adjustment [29, 36].

Practical barriers to long-term medication use

Patients described a variety of daily challenges they encountered that led to skipping or stopping their medication. These included financial difficulties in obtaining gout medications [23, 22, 25, 27, 38], forgetfulness [22–26, 31], taking multiple medications [25, 27, 31] and travelling [25, 27]. Nevertheless, patients adopted a variety of strategies to help them take their medications, including the use of medication dispensers (e.g. blister packs, pill boxes), alarm clocks and using daily routine activities as prompts to take their medication [23–25, 31, 38].

Discussion

Our aim was to provide a systematic review and thematic synthesis of provider and patient barriers to gout care from published qualitative studies. Based on 20 studies combining 480 gout patients and 120 providers, spanning five different countries across three continents, we found that among providers, the main barriers included substantial gaps in knowledge and education about gout management, treating gout as an acute condition (i.e. a treat-to-symptom approach), misconceptions about patients’ level of knowledge and corresponding adherence to therapy, and system-level constraints faced in clinical practice (e.g. limited time available to spend with gout patients). With regard to gout patients, the key barriers included limited knowledge about gout and its treatment, insufficient or negative interactions with providers, experiencing unexpected flares when beginning ULT and facing day-to-day challenges of taking long-term medications. These provider and patient barriers have important implications for key targets to improve the widespread suboptimal gout care [3, 7, 39, 40].

Our findings suggest that provider and patient barriers to care are closely intertwined, particularly with regard to the substantial gaps in knowledge and corresponding education about the disease and its management. Specifically, these knowledge gaps among providers are likely to contribute to patients’ reported lack of understanding of the causes of and treatment approaches for their gout. For example, patients were unaware of the role of uric acid in the development of gout, the availability and appropriate use of curative ULT, and the potential for paradoxical flares when initiating ULT. Indeed, similar knowledge gaps have been observed in earlier surveys of gout patients. For instance, in a US-based study, only 25% of gout patients receiving ULT were aware that that the medication was to be used chronically, and 12% were aware that beginning ULT could worsen gout in the short-term [41]. In a study conducted among patients in China, <30% reported that treatment with ULT was lifelong, and fewer than half of participants were aware of the SUA target level [42]. Indeed, effective patient education that communicates the key messages of gout (e.g. the direct causal role of hyperuricaemia and the curable nature of the disease) has been shown to improve patient outcomes substantially [43]. To that effect, both the ACR [44] and the EULAR [45] have developed strong consensus recommendations for gout care that emphasize the key components of successful management, including the importance of patient education. Therefore, our findings further emphasize the crucial role of education of patients as well as providers in successful gout management and underscore the importance of identifying and implementing knowledge translation strategies to patients and providers alike.

Our synthesis of qualitative literature also identified system-level barriers to care among providers as well as practical challenges faced by gout patients. For providers, this included the lack of an incentive and the limited time available to spend with each patient, and for patients this included forgetfulness and other daily logistical challenges. Although such challenges are inherent to the management of many chronic diseases requiring long-term care [46, 47], future work to improve gout care should also focus on identifying and implementing strategies to alleviate these system barriers to care experienced by physicians. Specifically, this suggests a potential role for non-physician health professionals, such as nurses and community pharmacists, who might represent a more readily accessible and cost-effective resource to provide appropriate gout education and follow-up, thereby ultimately improving gout care. These approaches would probably also facilitate provider efforts to work with patients in an effort to identify day-to-day strategies to prevent unintentional non-adherence to ULT, in addition to providing appropriate patient education.

Finally, the differing perspectives and management approaches held by physicians across the included studies further highlight the need to provide the urgently required high-level evidence for the benefit of treating to target SUA level (as opposed to the treat-to-symptom approach described by some providers across the included studies), as was recommended in the recent 2016 gout management guidelines published by the American College of Physicians [48].

The strengths and limitations of our study deserve comment. First, our synthesis expanded on several smaller published qualitative studies conducted among providers and patients by pooling their respective findings (for a total of 120 and 480 providers and patients, respectively, across five different countries) and identifying higher-level analytical themes to inform the development of future interventions targeting the widely reported suboptimal gout care [49]. Next, we systematically searched four electronic databases using a comprehensive search strategy developed by an experienced information scientist, thereby maximizing our capture of eligible studies. However, the inclusion of relevant studies might have been limited by publication bias as in any other systematic review. Nevertheless, unlike quantitative meta-analyses, the sample of a qualitative synthesis is purposive rather than exhaustive, because the aim is to provide interpretive explanation rather than prediction [20, 50].

In conclusion, our systematic review consistently identified gaps in knowledge among providers, which probably contribute to patients’ lack of proper education about the causes of and treatments approaches for gout. Furthermore, system barriers among providers and day-to-day challenges of taking chronic medications among patients are considerable. These factors provide key targets to improve the widespread suboptimal gout care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mary-Doug Wright, BSc, MLS, for constructing the database searches. Author contributions: Study conception and design: S.K.R., H.K.C., M.D.V.; Acquisition of data: all authors; data analysis and interpretation: all authors; manuscript drafting and critical review: all authors; final approval of manuscript: all authors. Dr M.D.V. holds a Canada Research Chair in Medication Adherence, Utilization and Outcomes and is a recipient of a Network Scholar Award from The Arthritis Society/Canadian Arthritis Network and a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Funding: This study was supported in part by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PCS 146388) and the Canadian Initiative for Outcomes in Rheumatology Care. This study was also supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01-AR-065944). The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of the study or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure statement: H.K.C. has received research grants from Pfizer and AstraZeneca to Massachusetts General Hospital for unrelated studies and served as a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Selecta, Horizon and Ironwood. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1. Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Zhang W. et al. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:649–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK.. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rai SK, Aviña-Zubieta JA, McCormick N. et al. The rising prevalence and incidence of gout in British Columbia, Canada: population-based trends from 2000–2012. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:451–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM.. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Int Med 2005;143:499–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M.. The changing epidemiology of gout. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2007;3:443–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharma TS, Harrington TM, Olenginski TP. Aim for better gout control: a retrospective analysis of preventable hospital admissions for gout [abstract]. In: American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, 2014.

- 7. Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, Zhang W, Doherty M.. Eligibility for and prescription of urate-lowering treatment in patients with incident gout in England. JAMA 2014;312:2684–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER 3rd, Gelber AC.. Gout, urate-lowering therapy, and uric acid levels among adults in the United States. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:588–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rees F, Hui M, Doherty M.. Optimizing current treatment of gout. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10:271–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rees F, Jenkins W, Doherty M.. Patients with gout adhere to curative treatment if informed appropriately: proof-of-concept observational study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:826–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M.. Concordance of the management of chronic gout in a UK primary-care population with the EULAR gout recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1311–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nasser-Ghodsi N, Harrold LR.. Overcoming adherence issues and other barriers to optimal care in gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015;27:134–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spencer K, Carr A, Doherty M.. Patient and provider barriers to effective management of gout in general practice: a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lindsay K, Gow P, Vanderpyl J, Logo P, Dalbeth N.. The experience and impact of living with gout: a study of men with chronic gout using a qualitative grounded theory approach. J Clin Rheumatol 2011;17:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Te Karu L, Bryant L, Elley CR.. Maori experiences and perceptions of gout and its treatment: a kaupapa Maori qualitative study. J Prim Health Care 2013;5:214–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lim SY, Lu N, Oza A. et al. Trends in gout and rheumatoid arthritis hospitalizations in the United States, 1993–2011. JAMA 2016;315:2345–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rai SK, Aviña-Zubieta JA, McCormick N. et al. Trends in gout and rheumatoid arthritis hospitalizations in Canada from 2000 to 2011. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:758–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mishra S, Satapathy SK, Mishra D. Improved search technique using wildcards or truncation. In: Intelligent Agent & Multi-Agent Systems, Chennai, India, 2009.

- 19. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J.. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas J, Harden A.. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arthritis Patient Advisory Board. Arthritis Research Canada. http://www.arthritisresearch.ca/our-team/arthritis-patient-advisory-board (4 July 2017, date last accessed).

- 22. Katz JL, Weiner H.. Psychobiological variables in the onset and recurrence of gouty arthritis: a chronic disease model. J Chronic Dis 1975;28:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harrold LR, Mazor KM, Velten S, Ockene IS, Yood RA.. Patients and providers view gout differently: a qualitative study. Chronic Illn 2010;6:263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martini N, Bryant L, Te Karu L. et al. Living with gout in New Zealand: an exploratory study into people's knowledge about the disease and its treatment. J Clin Rheumatol 2012;18:125–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh JA. Facilitators and barriers to adherence to urate-lowering therapy in African-Americans with gout: a qualitative study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh JA. Challenges faced by patients in gout treatment: a qualitative study. J Clin Rheumatol 2014;20:172–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh JA. The impact of gout on patient's lives: a study of African-American and Caucasian men and women with gout. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hmar RC, Kannangara DR, Ramasamy SN. et al. Understanding and improving the use of allopurinol in a teaching hospital. Intern Med J 2015;45:383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liddle J, Roddy E, Mallen CD. et al. Mapping patients' experiences from initial symptoms to gout diagnosis: a qualitative exploration. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Richardson JC, Liddle J, Mallen CD. et al. “Why me? I don't fit the mould … I am a freak of nature”: a qualitative study of women's experience of gout. BMC Womens Health 2015;15:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Onna M, Hinsenveld E, de Vries H, Boonen A.. Health literacy in patients dealing with gout: a qualitative study. Clin Rheumatol 2015;34:1599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chandratre P, Mallen CD, Roddy E, Liddle J, Richardson J.. “You want to get on with the rest of your life”: a qualitative study of health-related quality of life in gout. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:1197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Humphrey C, Hulme R, Dalbeth N. et al. A qualitative study to explore health professionals' experience of treating gout: understanding perceived barriers to effective gout management. J Prim Health Care 2016;8:149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jeyaruban A, Soden M, Larkins S.. General practitioners' perspectives on the management of gout: a qualitative study. Postgrad Med J 2016;92:603–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rebello C, Thomson M, Bassett-Clarke D, Martini N.. Patient awareness, knowledge and use of colchicine: an exploratory qualitative study in the Counties Manukau region, Auckland, New Zealand. J Prim Health Care 2016;8:140–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Richardson JC, Liddle J, Mallen CD. et al. A joint effort over a period of time: factors affecting use of urate-lowering therapy for long-term treatment of gout. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Spaetgens B, Pustjens T, Scheepers LEJM. et al. Knowledge, illness perceptions and stated clinical practice behaviour in management of gout: a mixed methods study in general practice. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:2053–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vaccher S, Kannangara DR, Baysari MT. et al. Barriers to care in gout: from prescriber to patient. J Rheumatol 2016;43:144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Edwards NL. Quality of care in patients with gout: why is management suboptimal and what can be done about it? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011;13:154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, Zhang W, Doherty M.. Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:661–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harrold LR, Mazor KM, Peterson D. et al. Patients' knowledge and beliefs concerning gout and its treatment: a population based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li QH, Dai L, Li ZX. et al. Questionnaire survey evaluating disease-related knowledge for 149 primary gout patients and 184 doctors in South China. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:1633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rees F, Jenkins W, Doherty M.. Patients with gout adhere to curative treatment if informed appropriately: proof-of-concept observational study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:826–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Khanna D, FitzGerald JD, Khanna PP. et al. 2012. American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1431–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E. et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gadkari AS, McHorney CA.. Unintentional non-adherence to chronic prescription medications: how unintentional is it really? BMC Health Services Res 2012;12:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA.. Management of acute and recurrent gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC.. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 2010;340:c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Doyle LH. Synthesis through meta-ethnography: paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qualitative Res 2003;3:321–44. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.