Abstract

Background

Computer templates for review of single long-term conditions are commonly used to record care processes, but they may inhibit communication and prevent patients from discussing their wider concerns.

Aim

To evaluate the effect on patient-centredness of a novel computer template used in multimorbidity reviews.

Design and setting

A qualitative process evaluation of a randomised controlled trial in 33 GP practices in England and Scotland examining the implementation of a patient-centred complex intervention intended to improve management of multimorbidity. A purpose-designed computer template combining long-term condition reviews was used to support the patient-centred intervention.

Method

Twenty-eight reviews using the intervention computer template and nine usual-care reviews were observed and recorded. Sixteen patient interviews, four patient focus groups, and 23 clinician interviews were also conducted in eight of the 12 intervention practices. Transcripts were thematically analysed based on predefined core components of patient-centredness and template use.

Results

Disrupted communication was more evident in intervention reviews because the template was unfamiliar, but the first template question about patients’ important health issues successfully elicited wide-ranging health concerns. Patients welcomed the more holistic, comprehensive reviews, and some unmet healthcare needs were identified. Most clinicians valued identifying patients’ agendas, but some felt it diverted attention from care of long-term conditions. Goal-setting was GP-led rather than collaborative.

Conclusion

Including patient-centred questions in long-term condition review templates appears to improve patients’ perceptions about the patient-centredness of reviews, despite template demands on a clinician’s attention. Adding an initial question in standardised reviews about the patient’s main concerns should be considered.

Keywords: delivery of health care, electronic health records, multiple chronic conditions, patient-centred care, primary health care, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Definitions of patient-centred care vary.1,2 Core components include an integrated holistic approach to the patient as a person, exploring and understanding the patient’s individual illness experience and concerns, achieving consensus on the health problem and its management, and enhancing the continuing relationship between patient and clinician. The broad aim is to achieve both patient involvement in care and the individualisation of care.3 Patient-centred care is encouraged for ethical and for pragmatic reasons, such as improved patient satisfaction and treatment adherence.4,5 As well as good empathy and communication skills, a patient-centred approach clearly requires a supportive environment,5 such as continuity of care.

Electronic disease templates are commonly used in many healthcare systems, including in the UK, to structure chronic disease management and data recording. In the UK, specially trained nurses usually conduct focused long-term condition (LTC) reviews using electronic templates, often discussing lifestyle issues and sometimes instigating changes to disease management. If patients wish to discuss other issues they need to make a separate GP appointment, with little opportunity for their health to be reviewed in the round.

Although there are advantages to template use that include facilitating information retrieval, quality control, and information exchange between patients and clinicians,6 there may be negative impacts in other ways. These include setting a restricted biomedical agenda for the consultation and inhibiting communication.7 Healthcare with a narrow disease focus can overlook other matters that are important to the individual.8 These factors all potentially have an adverse effect on patient-centredness, which may be compounded in patients with multimorbidity if they are recalled for separate, single-condition reviews by different specialist nurses within a practice.8

Using electronic disease templates and patient records can affect communication and the conduct of the consultation in several ways.7,9 Inputting data diverts the clinician’s attention and reduces eye contact, which often discourages the patient from speaking and may interrupt conversational flow, necessitating small talk to avoid silences.10 Completion of the template may become an end in itself, to be completed as quickly as possible,7 and questions may be framed to encourage a ‘no problem’ answer.11 The biomedical focus of templates combined with computer use may inhibit communication to the point that patients leave the consultation with unmet or undisclosed needs.7,12,13 Using a computer so that it does not disrupt the communication process requires skill, versatility, and familiarity with the electronic content.7,14,15

This article focuses on the use of a novel, purpose-designed template that supported patient-centred reviews of patients with multimorbidity participating in a multicentre cluster-randomised trial (the 3D Study)16 evaluating the effectiveness of a patient-centred approach to managing multimorbidity in GP practices. The aim of the article is to report an aspect of the process evaluation describing use of the novel template and whether, and how, it appears to influence patient-centredness.

How this fits in

Use of computer templates can compromise communication and patient-centredness by overriding patient agendas. This research finds that a new computer template, designed to encourage a patient-centred approach in long-term condition reviews, can enhance patient-centredness. Asking patients specifically about all of their health concerns at the start of a review can add value to the review. Patients feel they are viewed as a whole person and clinicians may identify unmet health needs.

METHOD

Setting

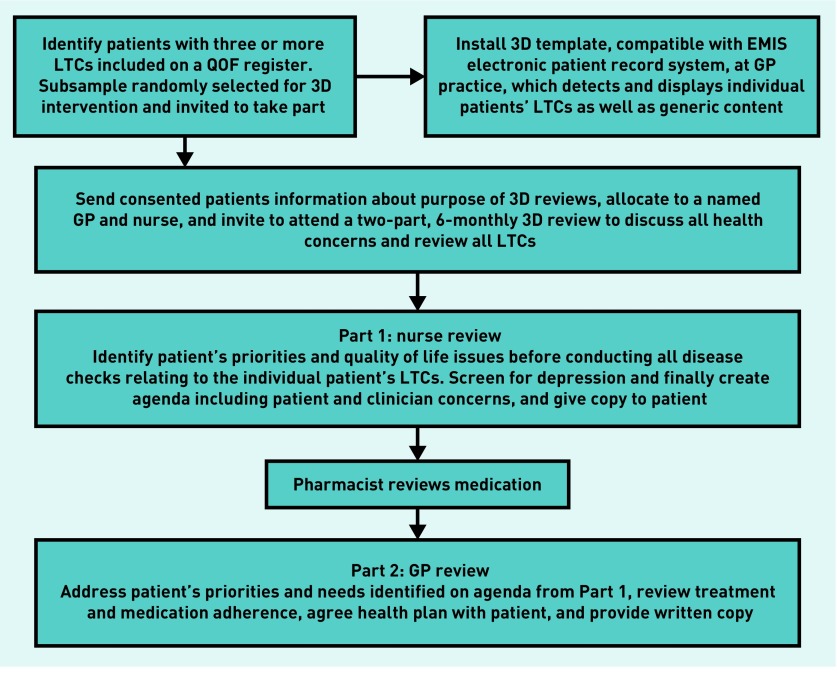

The 3D Study (3D stands for Dimensions of health, Drugs, and Depression, which were all targeted by the intervention to improve patients’ quality of life) recruited 33 GP practices and took place in three areas of England and Scotland.16,17 The patient-centred approach, defined with reference to well-known definitions,1,2,16 was incorporated in multiple intervention components, including comprehensive holistic two-part 3D reviews supported by the novel template and continuity of care (Figure 1). Three important aspects of patient-centredness were embedded in the 3D review template (Box 1), and the fourth was addressed by asking the practice to ensure continuity of care in arranging 3D patients’ appointments. Screenshots of the 3D review template are available from the authors on request.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the 3D intervention.

LTC = long-term condition. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Box 1. The 3D patient-centred approach and its relationship to intervention strategies.

| 3D definition of patient-centred care | Corresponding intervention components |

|---|---|

| 1. A focus on the patient’s individual disease and illness experience: exploring the main reasons for their visit, their concerns, and need for information | The 3D review template began with a question about patients’ most important concerns and then had questions about quality of life as part of a comprehensive review |

| 2. A biopsychosocial perspective: seeking an integrated understanding of the whole person, including their emotional needs and life issues | The 3D template included questions about quality of life, and incorporated depression screening. Continuity of care was intended to facilitate developing knowledge of patients’ circumstances |

| 3. Finding common ground on what the problem is and mutually agreeing management plans | The 3D template when completed produced a printable summary of the patient’s agenda based on patient’s primary concerns. The template also prompted development of printable collaborative management plans to address patients’ goals |

| 4. Enhancing the continuing relationship between the patient and doctor (the therapeutic alliance) | A named doctor and nurse allocated to each patient who would see the patient for every review and for interim visits to increase continuity of care |

The process evaluation of the 3D Study aimed to better understand how and why the intervention was effective or ineffective, and to identify contextually relevant strategies for successful implementation as well as practical difficulties in adoption, delivery, and maintenance to inform wider implementation. The full protocol is reported elsewhere.17 Case study methodology was used incorporating multiple methods to investigate the many aspects and stages of implementation in four case study intervention practices, supplemented by additional data from other participating practices to investigate emerging issues.

During the process evaluation, the central role of the 3D template in clinicians’ delivery of the intervention became apparent and prompted this investigation. Data were drawn from recordings of reviews, interviews, and focus groups, conducted for the overall process evaluation in a sample of 12 of the 33 practices participating in the 3D Study: eight intervention practices and four usual-care practices.

Sampling and data collection for review recordings

Four of the eight intervention practices were the process evaluation case studies, purposively sampled from 16 intervention practices to include each of the three geographical areas, and vary in size, deprivation index, similarity of usual care to the 3D intervention, and intervention set-up.17 In these case studies, it became apparent that 3D review delivery would vary by clinician more than by practice. Therefore, four additional intervention practices were sampled to extend the opportunity to observe variation among clinicians. One practice was purposefully chosen as the only practice where a research nurse was delivering reviews. Three were convenience sampled from the other two geographical sites in the trial because there was insufficient information to purposefully sample for clinician variation. Four usual-care practices were also convenience sampled, including at least one from each geographical site in the trial, to identify specific differences between 3D reviews and usual-care LTC reviews.

Within the eight intervention practices, 3D patients were purposively sampled for review observation and recording according to which clinician they were seeing, to maximise the number of different clinicians observed and achieve a range of nurse and GP reviews. Within the four usual-care practices, 3D patients were convenience sampled because of the difficulty of identifying observable reviews.

Data collection

First, naturalistic data from observations and review recordings were used to evaluate enactment of patient-centredness verbally and through body language, and to assess template use.18 A researcher identified possible observations, using the sampling criteria mentioned before, from lists of upcoming reviews sent by the practice. Selected patients received an invitation letter and information sheet, and were telephoned a few days later to discuss participation and obtain verbal consent. Once patients had agreed, the consulting clinician was asked for consent by email. Written consent to recording was obtained from the clinician and patient just before the review, and confirmed by patients with a second signature afterwards.

Patients and clinicians could choose video- or audio-recording. Patients generally had no preference, but most clinicians chose audio-recording, during which the researcher remained in the room to make notes on behaviour and interaction. The dataset included three videos and 25 audio-recordings of GPs and nurses from the eight intervention practices, and four videos and five audio-recordings from the four usual-care practices. Five nurses were recorded more than once.

Sampling and data collection for interviews

Second, in intervention practices the study conducted a mix of brief opportunistic and longer pre-scheduled post-review interviews with those patients and clinicians who were available, to elicit personal perspectives on individual reviews. Another consent form was signed prior to these interviews. Patients’ individual interviews took place at the practice immediately following the review or a few days later in their home or by telephone for between 10 and 45 minutes. Clinicians were interviewed at the practice for between 5 and 20 minutes. Ten clinician interviews and 10 patient interviews took place in this way.

To add to these interview data, other 3D patients in the case study practices were sampled for variety in health status and satisfaction with care at trial baseline, and took part in focus groups or individual interviews according to preference. Invited participants received a letter and information sheet, and were then telephoned to discuss participation. Six patients opted for individual interviews in a place convenient to them and 21 other patients who agreed attended one of four patient focus groups, one in each process evaluation case study practice. Two groups had three participants, one had seven, and the fourth had nine. They met for approximately one hour in a local hall or, in one case, in their practice meeting-room to discuss their experience of 3D reviews and explore divergent opinions. Written consent was provided, and a schedule guided the discussion (schedule available by request from the authors).

Furthermore, some clinicians in intervention practices were involved in end-of-trial interviews, arranged by sending an email invitation and conducted at the practice, with written consent provided at the time of interview. In total, 16 patients and 23 clinicians took part in some form of individual interview. In pre-scheduled interviews a topic guide was used (available from the authors on request). The review and interview data are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detail of review recordings and interview sample

| Individuals audio-recorded and observed or video-recorded (n separate reviews recorded) | Interviews | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Intervention | Usual care | Total | Intervention only | Total | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Audio | Video | Audio | Video | Post-review | End-of-trial | |||

| GPs, n | 12 | 3 | 0 | 1a | 16 (16) | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Nurses, n | 9b (13) | 0 | 3c (5) | 2d (3) | 14 (21) | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Patients, n | 21e (25) | 3 | 5 | 4 | 33 (37) | 10 | 6 | 16 |

As only one review recorded, GP usual care has not been discussed in the results.

Two nurses audio-recorded/observed twice; one nurse audio-recorded/observed three times.

One nurse audio-recorded/observed three times.

One nurse video-recorded twice.

Four patients were recorded having a nurse and GP review back-to-back.

Analysis

All recordings were professionally transcribed. Each transcript was checked, anonymised, and, for review recordings, annotated with observation notes about body language and actions, including direction of gaze for the video-recordings. Review recordings, clinician interviews, and patient interviews (including focus groups) were initially coded separately with their own framework of codes using NVivo 11. The coding frameworks each combined a priori codes drawn from intervention components and core aspects of patient-centredness (Table 1) and data-derived codes. Box 2 presents the coding framework for the review recordings, showing how codes were combined into the themes reported in this article.

Box 2. Coding framework used for analysing review observations.

| Initial codes | Framework matrix themes | Overarching themes (patient-centredness criteria) |

|---|---|---|

| Eliciting concerns Closing off No problem preferred Agreeing patient agenda Agenda balance Clinician agenda Other problems raised Individual illness experience Exploration of issues Follow-up |

Opening of consultation Eliciting concerns and setting agenda Exploration of issues Understanding illness experience |

Agreeing patient agenda (Includes: a focus on the patient’s individual disease and illness experience, finding common ground on what the problem is) |

| Quality of life Depression screening Psychosocial |

Psychosocial |

Biopsychosocial perspective (A biopsychosocial perspective) |

| Negotiation Finding common ground Health plan Goal-setting Summarising and clarifying |

Finding common ground Health plan and action summaries |

Health plan (Mutually agreeing management plans) |

| Building relationship Continuity |

Continuing relationship |

Continuing relationship (Enhancing the continuing relationship between the patient and doctor/nurse) |

| Template | Use of template | Use of template |

| Body language |

The review recordings data were summarised in a matrix organised into nurse and GP reviews, and then divided into intervention and usual care. Each review occupied a row and each theme a column. The cells contained a short summary of each review by theme to facilitate comparison. A matrix was also created for the clinician data and another for patient interview and focus group data. For these data, coded extracts pertaining to patient-centredness and template use were extracted from NVivo, re-coded and summarised under the relevant matrix theme. The matrices were used to compare themes across datasets.

Double coding of eight review transcripts was undertaken by two members of a patient public involvement (PPI) group and a further 12 review and interview transcripts were double-coded by three researchers. Three transcripts were also discussed with the whole PPI group. This helped clarify patient-centredness, confirm themes, and identify divergent opinion. Differences in perceptions of patient-centredness were discussed to elucidate reasons.

In all quotes in the results, case study practices are referred to by pseudonyms, for example, Beddoes, and other intervention practices by Int1–5. GPs, nurses, and patients are referred to as GP, NU, and Pt, respectively, with a number and a practice identifier.

Reflexivity

The researcher who undertook the data collection and analysis was previously a nurse and researcher in GP practices. This gave insight into nurses’ conduct of LTC reviews and how practices worked but it was necessary to guard against over-identification with nurse colleagues. Awareness of this helped to maintain objectivity.

RESULTS

Use of template

In both intervention and usual-care observed reviews, computer use that caused loss of eye contact disrupted dialogue. Patients often waited to speak until the clinician had finished data entry or information retrieval. This sometimes seemed an intentional strategy by clinicians, who resumed eye contact to reinforce communication, solicit specific information, or provide instruction. Computer activities caused less disjunction when screen positioning did not require clinicians to turn right away from the patient, and clinicians could switch their attention more easily between patient and computer or share the displayed information. In nurse usual-care reviews, patients more often continued to talk while data was being entered, suggesting that, like the nurses, they were generally relaxed with a familiar process. Some nurses reduced computer use by working from a printed checklist and making handwritten notes to enter later.

Nurses conducting 3D reviews had no objections to templates per se, and some liked how the 3D template combined each patient’s reviews. However, the different structure and unfamiliarity forced them to attend carefully to the template, which was noticed by patients:

‘Because it’s quite new I’m going to talk through the template because although I’ve probably done about 20 of these they’re still not coming off like the patter like I’m used to.’

(Harvey, NU1, observation [O])

Some nurses had difficulty due to multiple diseases being reviewed on the same occasion and questions they did not fully understand. The template also lacked some fields they expected from their usual templates:

‘I was always very concerned that I would be missing something … because I was going from asthma to diabetes to depression … all over the place, I was concerned that not each particular condition was being given the focus that it needed.’

(Int5, NU1, interview [I])

Like nurses, GPs used the 3D template to structure care, which was evident in how they turned to it to confirm or explain their next step:

‘So, we’ve done the bit on medication. And now we’re going to get to the bit where we … make some plans for things we’re going to achieve in the next 6 months. Okay?’

(Harvey, GP1, O)

However, GPs had a shorter template to complete and often integrated it more smoothly into their review so it seemed less dominant than in nurse reviews. In interviews, most GPs could see benefits of the template, such as the prompt to check medication adherence, which was not typically part of usual practice. A few found it frustrating and one GP clearly resented the template:

‘What you need in that longer appointment is not to be sat reading a screen, which I found I was doing a hell of a lot more than I would in a normal consultation … I don’t want a load of prompts and a load of forms to fill in and click and buttons.’

(Davy, GP1, I)

Establishing patient agenda

Usual-care nurse reviews usually began with confirmation that the appointment was to review the patient’s LTC(s). Patients sometimes raised other concerns when initially asked how they were, for example, back pain, but the LTC review took precedence and other concerns may have been closed off or ignored.

The 3D nurse reviews began similarly with a social greeting and the purpose of the appointment. The big difference was in the first question of the review template:

‘What is the most important health problem that you would like us to work on over the next few months?’

This, and questions about quality of life, preceded the LTC reviews. However, tension between allowing the patient to raise their concerns and completing the LTC review was sometimes evident. The following triple question effectively inhibited the patient from voicing their own concerns:

‘What do you see as the most important health problem that you’d like us to work on over the next couple of months? Is there anything in particular that’s concerning you or bothering you? Is your asthma well controlled at the moment?’

(Beddoes, NU1, O)

Usually the question was asked as it appeared on the template and prompted patients to talk about a wide range of health concerns, often unrelated to their existing LTCs. Wording varied when recording concerns on the agenda. They were often generalised or in medical language and very rarely exactly as the patient had stated them. Although nurses often checked the wording with patients, few patients corrected it:

‘So, shall we say you get gastric problems?’

(Lovell, NU1, O)

Several clinicians, especially GPs, questioned the appropriateness of some concerns raised by patients, seeing them as less important than the LTC(s) under review and others expressed frustration over having to revisit problems that could not be resolved:

‘She had a load of things she wanted to talk about which were irrelevant to her … chronic disease management … it was “I want to talk about the numbness in my feet I have had for 20 years.”’

(Davy, GP1, I)

However, most clinicians highly valued the enquiry about the patient’s agenda and saw it as novel. Some identified unmet health needs through patients revealing previously unmentioned symptoms, leading to new diagnoses, for example, melanoma, heart failure, and hip osteoarthritis.

GPs usually began their 3D reviews by referring to the nurse review and patient agenda. Some GPs confirmed its contents with the patient; others preferred to agree an agenda themselves.

Patients sometimes did not bring their copy and occasionally GPs disregarded it, whereas others valued receiving a guide for the consultation:

‘You know what you’re here for. You’ve seen the nurse and you’ve spoken to the [pharmacist] on the telephone, haven’t you? Fine okay. So … I’ll open this up, [opens 3D template on computer] which tells us what the worries are, okay?’

(Beddoes, GP2, O)

Patients’ comments on being asked about all their concerns were very positive. They felt heard, and they valued the comprehensive, thorough, and holistic nature of the review. This gave some a sense of empowerment:

‘This gives me that kind of overview where you think “well I’m the person that’s getting attended here, it’s not what this GP wants or thinks it’s what … my needs are”.’

(Lovell, Pt7, focus group)

However, one patient expressed dissatisfaction because their GP lacked knowledge of their rare condition and so had taken their main concern off the agenda.

Sometimes concerns were overlooked, for example, a very swollen knee was not addressed because the nurse had described it generically on the agenda as a pain and mobility problem.

Biopsychosocial perspective

In usual-care reviews, although nurses were frequently observed referring to their patients’ social circumstances, they did not specifically address quality of life or mental health. The questions in the 3D template about wellbeing and depression provided opportunities to explore psychosocial issues, despite some nurses’ discomfort with some of the unfamiliar depression screening questions:

‘Feeling bad about yourself or … that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down? I just hate asking that question.’

(Harvey, NU2, I)

Some nurses ran through questions quickly in a way that favoured a no problem response. However, one nurse spent 19 minutes completing the depression screening because each question triggered a discussion of the patient’s circumstances, preferences, and feelings.

GPs frequently showed awareness of biopsychosocial issues and would often ask or already have information about patients’ mood, social circumstances, and family situations. Where this was not evident it usually did not seem relevant to the problem under discussion. Whereas nurses engaged conversationally with patients’ social circumstances, most GPs referred to biopsychosocial aspects in the context of patients’ health:

‘He takes an interest and he’s not so much kind of the medical model, he’s not so much looking at me in terms of the illness, he’s looking more at me and how it’s affecting me.’

(Lovell, Pt6, I)

Agreeing health plan

Most usual-care reviews concluded with a verbal management plan, but 3D nurse reviews concluded with creating an agenda for the GP review, leaving nurses no obvious role in agreeing management plans. However, many nurses continued to advise on LTC management and some skilful negotiations were observed with the nurse eliciting and accommodating patient preferences, for example, regarding change of medication, home blood pressure monitoring, and diet.

In GP 3D reviews, the template required a health plan, which stated the problems and included actions that the patient and GP could take to address them. Some patients liked having a printed health plan, but many did not remember receiving one. Some GPs felt the way the plan was formulated was patronising and artificial, and they often found difficulties in printing the plan. Many patients were not given or did not remember receiving a printed copy.

Almost all health-plan actions were proposed by the GP and usually agreed by the patient. Some patients disliked the proposed action or perceived it as not suggesting anything worthwhile or addressing their agenda:

‘She wanted me to get gardening but not [in] this weather I’m afraid.’

(Harvey, Pt7, I)

However, there were some examples of genuine collaboration, in line with a patient-centred approach, and one GP was surprised by some goal suggestions.

‘Sometimes patients do come up with a totally different goal that I had never dreamt of.’

(Harvey, GP1, I)

Comparing findings

Boxes 3 and 4 summarise the findings and compare themes across datasets facilitating comparison of usual care and the intervention regarding template use and patient-centredness of nurses and GPs.

Box 3. Comparison of different review types by theme, based on observation data.

| Type of data | Themes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of template | Establishing patient agenda | A biopsychosocial perspective | Agreeing health plans | |

| 3D nurse review observations | Template intrusive, was followed closely and determined questions and structure. Nurses often explicitly referred to it to explain content of review. Data entry interrupted flow. Unfamiliarity with template slowed them down | Elicited wide-ranging patient concerns, explored in detail. Musculoskeletal concerns less likely to be explored. Often categorised simply as pain and mobility problems. Validation and prioritisation of patient’s agenda in most cases | Covered formally in every review because of template. Template questions about quality of life and PHQ-9 questionnaire could prompt exploration of psychosocial issues | Management plans removed from nurse responsibility, but some nurses negotiated actions concerning long-term conditions within their own expertise |

| Usual-care nurse review observations | Template structured the reviews but not intrusive as patients and nurses were familiar with it. Usually completed during review | Restricted to reason for review. Other unrelated problems occasionally raised but not explored in depth |

Evident in many observations but mainly taking the form of social enquiry | Usual conclusion to review was to summarise actions agreed or confirm no change to management |

| 3D GP review observations | Template mostly followed but in a more free-form way than by 3D nurses. Some overtly referred to template when checking review was complete and printing health plan. Data entry less intrusive than in nurse reviews. Template use sometimes not obvious |

Varied in extent to which previously compiled agenda was used. Not all GPs explored problems on patient agenda because: they lacked expertise; old problem; nothing new to add; or considered not relevant. Some new problems were identified | In two-thirds of reviews there was evidence of in-depth understanding of psychosocial issues. In others, often where not obviously relevant to problems to be addressed, there was no evidence | Health plans agreed in almost all cases. Occasional patient suggestions but mainly GP suggestions agreed to by patient and all formulated by GP rather than patient. Written plan not always provided |

| Usual-care GP review observation | Had to rely on computer to look up information in patient record, which was time consuming | Patient wanted to talk about other problems, not LTCs. GP reviewed LTCs and medications at length, then addressed other problems | Not evident | Prescriptions given and stated when to review |

LTC = long-term condition. PHQ-9 = nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Box 4. Patient and clinician perceptions by theme, based on interview and focus group data.

| Type of data | Themes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of template | Establishing patient agenda | A biopsychosocial perspective | Agreeing health plans | |

| Patient interviews and focus groups | A couple of patients commented that the 3D template distracted the clinician’s attention and/or slowed them down | Patients glad to be ‘allowed’ to talk about all their problems in 3D reviews and to have an all-round review | One patient impressed by questions put by GP who he had not previously seen. Some patients’ needs for depression treatment recognised during review | Some patients appreciated these but many reported not receiving one, or it not having been agreed collaboratively |

| Clinician interviews | Some GPs disliked being constrained by a template. Nurses had criticisms about the content and some found it unwieldy. Unfamiliarity with it hindered them. A few nurses and GPs welcomed the template | Novel to ask explicitly about patient agenda and focus on that. Some clinicians said it would change future practice. Some issues patients raised were not considered appropriate because intractable or outside the remit of the review | Nurses not always comfortable with administering PHQ-9 questionnaire | Some nurses felt their disease management role had been reduced. Some GPs liked the written health plan as a record of what had been agreed but many were uncomfortable with it; felt it was artificial and trivial; they preferred a verbal summary in accordance with their usual practice |

PHQ-9 = nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Although the 3D template increased disruption to communication compared with usual-care reviews, patients experienced 3D reviews as more patient-centred. The template contributed questions about patients’ most important problems, quality of life, and mood, which uncovered a wide range of patients’ concerns including unmet health needs, and an individualised patient agenda. Whether patients’ agenda items were all subsequently addressed by the GPs depended partly on how nurses framed them and GPs’ skills and priorities, but many clinicians valued hearing about patients’ own concerns and quality of life.

Being reviewed as a whole and asked about their health priorities was experienced by patients as more personal than usual care. Other important factors were feeling listened to and experiencing a liberating sense of having time and permission to raise other concerns, in contrast with more constrained usual-care appointments. Some patients described these changes as novel and empowering.

The 3D health plans were less successful and less valued by GPs or patients. Plans were often GP-led, rather than patients shaping the management of their health according to goals they had identified. The medicalisation of concerns recorded on the patient’s agenda and skill deficits in enacting genuine shared responsibility in creating and achieving health goals may have contributed. Patients may need time to get used to a new approach and a few patients referred to a lack of meaningful negotiation.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study lie in the range of data, including observation of both intervention and usual-care reviews. Interviewing both patients and clinicians complemented the observations and enabled data triangulation, although not in usual-care reviews. PPI involvement in analysis provided an additional perspective on patient-centredness of a subset of recorded reviews. A potential limitation was that sample size was constrained by funding and trial time frames. However, each theme contained a range of views and observations, gathered through a variety of methods, which were judged to have sufficient information power to address the aims of this study.19

It could not be ascertained how much the template alone influenced patient-centredness. Clinicians had had training for the 3D study that covered the challenges facing patients with multimorbidity, eliciting patients’ priorities, and negotiating a shared approach to the patients’ health problems.

Observing reviews may have influenced the data as clinicians were very conscious of the observer’s presence and may have changed how they conducted the review. In intervention reviews, clinicians may have felt under scrutiny, perhaps explaining the lower proportion of intervention video-recordings, compared with usual care. Patients seemed generally less aware of the researcher, but some interacted with her during the review.

Comparing intervention reviews with usual-care reviews helped to assess the effect of the 3D template but the researchers were unable to meaningfully compare GP 3D reviews with the one GP usual-care review. Instead, the researchers contrasted current practice of LTC reviews conducted by nurses with 3D reviews in which both nurse and GP were involved.

Comparison with existing literature

Various common consequences of template use described in the literature were observed in the use of the 3D template.7,10,14,20 Positive consequences included providing structure, promoting thoroughness and consistency, facilitating information recording and retrieval, and gauging progress against goals.6,21 Negative consequences included disruption of communication, which was exacerbated by use of the unfamiliar 3D template7,9,14 and routinisation of enquiry, with questions asked to suggest particular or closed answers.11,13 It is possible that adjustments to the template, based on feedback from clinicians, might reduce these consequences. Occasional deliberate use of the computer to close off patient communication, previously observed elsewhere,18 was also noted in the present study.

Although template use can detract from patient-centredness by overriding patients’ agendas, and imposing professional priorities,7,13 patients’ increased perception of patient-centredness in this study indicated that the 3D computer template reversed this effect by first prompting clinicians to explore patients’ illness experience. However, as with other templates, there was a danger of conflating template completion with care delivery. Clinicians’ responses suggested that some did equate the template with the intervention and that their underlying patient-centred consultation skills consequently did not change. The health plan findings suggest that more thought needs to be given to its format and use, both in terms of skill and how it might be used with patients coping with deprivation, poor health literacy, and linguistic ability. Further research might usefully identify a more effective way of addressing these intervention issues.

Implications for practice

The findings of this study suggest that patient-centredness can be influenced by the content of the template, not just by template use alone. A template for reviewing multiple LTCs that explicitly incorporated questions about patient priorities, and asked these first, established a focus on the patient’s perspective. This could help to change clinicians’ behaviour towards a more equal agenda balance and patients’ behaviour towards seeing reviews as an opportunity to take greater ownership of their health. Including an enquiry about patients’ main health concerns as the first question on every LTC review template and building in other patient-centred questions should be considered as a means of supporting a patient-centred approach.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are owed to Ruth Sayers and Judith Brown who double-coded some transcripts, and other members of the PPI group who contributed thoughtful comments and discussion about patient-centredness of reviews. The authors are very grateful to the patients and clinicians who consented to be interviewed and/or have reviews recorded, the practices who consented to take part, and their administrators, who helped identify possible participants for this project.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research, Health Services and Delivery Research (NIHR) Programme (project number 12/130/15). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the above funder, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by South West (Frenchay) NHS Research Ethics Committee (14/SW/0011).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):444–445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):1087–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(12):600–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazmi Z. Effects of exam room EHR use on doctor–patient communication: a systematic literature review. Inform Prim Care. 2013;21(1):30–39. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v21i1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swinglehurst D, Greenhalgh T, Roberts C. Computer templates in chronic disease management: ethnographic case study in general practice. BMJ Open. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD003267. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greatbatch D, Heath C, Campion P, Luff P. How do desk-top computers affect the doctor–patient interaction? Fam Pract. 1995;12(1):32–36. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Street RL, Jr, Liu L, Farber NJ, et al. Provider interaction with the electronic health record: the effects on patient-centered communication in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murdoch J, Varley A, Fletcher E, et al. Implementing telephone triage in general practice: a process evaluation of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:47. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chew-Graham CA, Hunter C, Langer S, et al. How QOF is shaping primary care review consultations: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes P, Langdon M, Rowley E, et al. What does the use of a computerized checklist mean for patient-centered care? The example of a routine diabetes review. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(3):353–376. doi: 10.1177/1049732305282396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noordman J, Verhaak P, van Beljouw I, van Dulmen S. Consulting room computers and their effect on general practitioner–patient communication. Fam Pract. 2010;27(6):644–651. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swinglehurst D, Roberts C, Li S, et al. Beyond the ‘dyad’: a qualitative re-evaluation of the changing clinical consultation. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e006017. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Man MS, Chaplin K, Mann C, et al. Improving the management of multimorbidity in general practice: protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial (the 3D Study) BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e011261. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann C, Shaw A, Guthrie B, et al. Protocol for a process evaluation of a cluster randomised controlled trial to improve management of multimorbidity in general practice: the 3D study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e011260. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverman J, Kinnersley P. Doctor’s non-verbal communication in consultations: look at the patient before you look at the computer. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X482293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jinks C, Carter P, Rhodes C, et al. Patient and public involvement in primary care research — an example of ensuring its sustainability. Res Involv Engagem. 2016;2:1. doi: 10.1186/s40900-016-0015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]