SUMMARY

The Plasmodium cell cycle, wherein millions of parasites differentiate and proliferate, occurs in synchrony with the vertebrate host’s circadian cycle. The underlying mechanisms are unknown. Here we addressed this question in a mouse model of Plasmodium chabaudi infection. Inflammatory gene expression and carbohydrate metabolism are both enhanced in IFNγ-primed leukocytes and liver cells from P. chabaudi-infected mice. TNFα expression oscillates across the host circadian cycle, and increased TNFα correlates with hypoglycemia and a higher frequency of non-replicative ring forms of trophozoites. Conversly, parasites proliferate and acquire biomass during food intake by the host. Importantly, cyclic hypoglycemia is attenuated and synchronization of P. chabaudi stages is disrupted in IFNγ−/−, TNF receptor−/− or diabetic mice. Hence, the daily rhythm of systemic TNFα production and host food intake set the pace for Plasmodium synchronization with host’s circadian cycle. This mechanism indicates that Plasmodium parasites take advantage of the host’s feeding habits.

Keywords: Energy metabolism, food intake, IFNγ, TNFα, glucose, insulin, Plasmodium, malaria and circadian cycle

eTOC

A hallmark of Plasmodium infection is a cyclic fever preceded by the synchronized rupture of infected erythrocytes. How millions of parasites proliferate synchronously is unknown. Hirako et al. found that inflammation-induced hypoglycemia impairs parasite replication, whereas Plasmodium proliferates during host food intake, which parallels the host’s circadian cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is among the most devastating infectious diseases in the world (Miller et al., 2013). A pathognomonic sign of Plasmodium infection is a cyclic paroxysm preceded by the synchronized release of parasites from infected red blood cells (RBCs). The simultaneous bursting of millions of RBCs expels parasite and host components that activate innate immune cognate receptors culminating in a massive release of pyrogenic cytokines, e.g., IL-1β and TNFα. The sharp peaks of high fever, chills, and rigors may also associate with other pathological processes such as respiratory distress, anemia, and neurological manifestations, which relate to the intensity of the malaria-induced cytokine storm (Gazzinelli et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2013).

The cell cycle of some Plasmodium species parallels the host circadian rhythm; however, the mechanism that controls parasite synchronization is a major knowledge gap in Plasmodium biology (Hawking, 1970; Mideo et al., 2013). Host circadian rhythm controls a variety of physiological events including energy metabolism; conversely, the host circadian clock is influenced by host habits, such as food intake, physical activity, and metabolism (Curtis et al., 2014; Eckel-Mahan and Sassone-Corsi, 2013). Importantly, cellular metabolism influences and is influenced by host immune responses. For instance, monocyte differentiation from a resting to an inflammatory state requires a shift in energy metabolism to high glucose consumption and rapid energy generation by glycolysis (Mills et al., 2017), whereas inflammatory cytokines promote glucose uptake and metabolism by different host cell types (Sakurai et al., 1996; Vogel et al., 1991). Furthermore, immune response and dietary restriction limit biomass acquisition and Plasmodium proliferation in the vertebrate host (Mejia et al., 2015). Here, we investigated whether host inflammatory responses and energy metabolism influence synchronization of Plasmodium blood stages.

Important contributions to understanding malaria have come from the P. chabaudi (Pc) mouse model, which displays striking hematological similarities to P. falciparum (Stephens et al., 2012). Mice are nocturnal and the Pc cell cycle is completed in 24 h, suggesting a circadian basis. After invasion, intra-erythrocytic merozoites differentiate into low-energy-consuming ring-form trophozoites and then mature trophozoites that are maintained in a non-replicative stage during the host-resting phase at daytime, whereas schizogony and burst of infected RBCs occur in the active phase at nighttime (David et al., 1978; Hotta et al., 2000; Mideo et al., 2013). Our findings suggest that synchrony of Pc stages is controlled by a cyclic release of TNFα and hypoglycemia, whereas parasite proliferation occurs during host food intake, when blood glucose levels are transiently higher. Hence, pro-inflammatory response and food intake are important pacemakers of Plasmodium cell cycle synchrony with vertebrate host circadian rhythmicity.

RESULTS

An energy metabolism transcriptional signature in leukocytes from malaria patients

Professional phagocytes play an important role in the pathophysiology of malaria. These innate immune cells are IFNγ-primed and, upon activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) produce high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (Antonelli et al., 2014; Ataide et al., 2014; Franklin et al., 2009; Hirako et al., 2016). Thus, we examined cytokine production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from malaria patients. PBMCs consistently produced high levels of IL-1β, IL-12 (p70), and TNFα and low levels of IL-10 when stimulated either with LPS (TLR4 agonist) or R848 (TLR7/8 agonist), whereas under the same conditions, leukocytes from healthy donors produced low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and high levels of IL-10 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Energy metabolism gene signature and pro-inflammatory response in P. falciparum malaria patients.

(A) Cytokine levels in PBMCs from malaria patients and healthy donors, cultured in the absence or presence of LPS (100 ng/mL) or R848 (2 µM). Data are the average of PBMCs from 5 healthy donors and 5–6 malaria patients. Student’s unpaired t test with Welch’s correction was used for data analysis with parametric distribution. Statistically significant differences are indicated by *p<0.05, **p<0.01, or ***p<0.001. (B) Heatmap illustrating the differential expression of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism (glucose metabolism as well as glucose 6-phosphate processes and galactose catabolism), canonical glycolysis pathway, reduction-oxidation reactions (cell redox homeostasis and respiratory burst), and response to oxidative stress by PBMCs of malaria patients before and after treatment. (C) GSE Reactome analysis indicates inflammatory and metabolic pathways induced in patients undergoing acute malaria episodes. Red and blue dots indicate that the named pathways are enriched for enhanced gene expression in individuals with malaria, before and after therapy and parasitological cure, respectively. The color scheme represents the global Z-score. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

A recent study demonstrated reprogramming of energy metabolism in inflammatory leukocytes (Mills et al., 2017). To investigate if energy metabolism is altered in leukocytes from P. falciparum-infected subjects, we analyzed the gene expression profiles of PBMCs from clinically-ill patients. White blood cells from acute malaria patients exhibit gene signatures related to carbohydrate metabolism, glycolysis, oxidation-reduction reactions, respiratory burst, and response to oxidative stress. These expression signatures are no longer present after parasitological cure (Figure 1B). Gene ontology and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis using Reactome pathways indicate that IFNγ signaling, TLR cascades, inflammasome components, and glucose metabolism are among the highest induced genes in leukocytes from symptomatic patients (Figures 1C and S1). Altogether, our analyses indicate that carbohydrate metabolism is boosted in inflammatory leukocytes from malaria patients.

Carbohydrate metabolism and inflammatory gene signatures are disrupted in splenocytes from P. chabaudi-infected IFNγ−/− mice

We next asked if our findings in leukocytes from P. falciparum malaria patients could be replicated in the Pc mouse model. Consistent with the gene expression changes observed in human cells, expression profiling of splenocytes from Pc-infected mice revealed transcriptional signatures related to pro-inflammatory pathways, carbohydrate metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, pyruvate metabolism, the citric acid cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and insulin signaling including mTOR pathways (Figures 2A and S2A). IFNγ mediates an mTOR-HIF-1-dependent metabolic switch to glycolysis leading monocytes into a pro-inflammatory state (Mills et al., 2017) and enhances pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis by both human and mouse inflammatory cells from Plasmodium-infected hosts (Antonelli et al., 2014; Ataide et al., 2014; Franklin et al., 2009; Hirako et al., 2016). Importantly, we observed that the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and TLR-induced genes as well as carbohydrate metabolism, glycolysis, and pyruvate metabolism genes during Pc infection were partially dependent on endogenous IFNγ (Figures 2B and S2B). Stimulation of splenocytes derived from Pc-infected mice with TLR7 (R848) and TLR9 (CpG) agonists elicited cytokine profiles consistent with a pro-inflammatory response (high IL-6, MCP1, TNFα and low IL-10) similar to that observed in human cells from acute malaria patients and stimulation of splenocytes from uninfected mice had an anti-inflammatory profile (low IL-6, MCP1, TNFα and high IL-10) similar to healthy donors (Figures 1A and 2C). Thus, the Pc mouse model resembles human disease and is useful to ask mechanistic questions about the influence of pro-inflammatory responses and energy metabolism on host-parasite interaction.

Figure 2. Energy metabolism gene signature and parasite synchronization is disrupted in Pc-infected IFNγ−/− mice.

(A) Heatmap of microarray results illustrating differential expression of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism (pentose phosphate pathway, galactose, fructose, and mannose metabolism), glycolysis and gluconeogenesis pathways, pyruvate metabolism, citrate (TCA) cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and insulin response including the mTOR signaling pathway by splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice (3 uninfected and 3 Pc-infected). (B) Radar illustration of: (i) the number of genes (fold change >1.5) from different inflammatory or metabolic pathways induced in spleen from Pc-infected C57BL/6 (WT) mice (blue line); (ii) the percentage of these genes with a >1.5-fold change in infected IFNγ−/− mice (red line); and (iii) the percentage of these genes for which the expression was higher in infected WT than in infected IFNγ−/− mice (green line). (C) Cytokine levels produced by splenocytes cultured in the absence or presence of CpG ODN (3 µM) or R848 (2 µM). Data are the average of 5–8 uninfected controls and 7–10 infected mice at 8 days p.i. and results are a pool of two independent experiments. Analyses of cytokine results were performed using Mann-Whitney test for data with non-parametric distribution. (D) The three-way interaction was significant (p=0.02); for Day 8 there was a significant difference in trends over time between infected IFNγ−/− (n=17) and infected WT mice (n=24) (p=0.0056). Differences in means of blood glucose levels are statistically significant, when comparing infected IFNγ−/− and infected WT mice at the same time point, as indicated by * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) and ***(p<0.001) indicate. There was a significant difference in trends at Day 0 (p=0.02) with slightly higher level in IFNγ−/− (n=16) at 12 hours, when compared to WT (n=34). Data are a pool of 5 experiments with similar results. (E) Concavity measurements, confidence intervals (within brackets) and p values (in each graph) indicate that the different Pc stages are evenly distributed in IFNγ−/− mice (n=7) at different time points, when compared to WT mice (n=13). Ring: WT C=−1.41 [−1.55, −1.26] versus IFNγ−/− C=−0.18 [−0.38, 0.02]; Trophozoite: WT C=1.01 [0.88, 1.15] versus IFNγ−/− 0.20 [0.02, 0.38]; and Schizont: WT C=0.39 [0.33, 0.046] versus IFNγ−/− −0.03 [−0.12, 0.06]. Data are pool of 3 experiments Estimates and testing based on mixed effect model (glucose) or multivariate mixed effect model (parasitemia) with mouse as a random effect as described in the methods section. See also Figure S2 and Table S2.

Rhythmic oscillation of blood glucose levels is associated with P. chabaudi cell cycle synchronization

While the metabolic phenotype of leukocytes is associated with their inflammatory potential, it is clear that inflammation induced by infection and pro-inflammatory cytokines has a reciprocal effect on host circadian cycle and metabolism (Curtis et al., 2014). To evaluate the connection between IFNγ-induced responses, host energy metabolism and parasite synchronization, we examined the expression of both insulin response genes in leukocytes and the circulating glucose levels in Pc-infected mice. WT mice infected with Pc displayed insulin response and mTOR pathway gene signatures, which were less pronounced in Pc-infected IFNγ−/− mice (Figures 2B, S2A, and S2B). Zeitgeber time (ZT) 0 to 12 and 12 to 24 h define light and dark time, respectively, independent of the daytime. Hence, we will use ZT to indicate light and dark time in each experiment. Infected C57BL/6 mice are hypoglycemic with a main drop in circulating glucose levels at ZT 23 (end of active/dark period), whereas hypoglycemia in Pc-infected IFNγ−/− mice was attenuated at ZT 23 (Figure 2D).

Intra-erythrocytic trophozoites can be grouped into non-replicative ring and mature forms. The ring form contains a small, delicate, thin ring of cytoplasm, a vacuole, and a prominent chromatin dot, whereas mature trophozoites contain one or two nuclei with an enlarged cytoplasm. During parasite proliferation, schizonts with multiple nuclei are formed (Figure 2E). We show that the synchronized differentiation and replication of Pc as well as hypoglycemia at ZT 23 is cyclic for at least three consecutive days (i.e., 6, 7 and 8 days post-infection), suggestive of a circadian basis (Figures S2C and S2D). Importantly, hypoglycemia associated with a high frequency of ring-form trophozoites (ZT 23), whereas schizonts were most frequent when blood glucose levels were higher (ZT 17). Intriguingly, the frequency of all three parasite stages was similar at the different time points across the circadian cycle in IFNγ−/− mice (Figures 2E and S2E). Thus, endogenous IFNγ has an important role in boosting host energy metabolism in leukocytes, regulating blood glucose levels, and controlling Pc synchronization with the mouse circadian rhythm.

IFNγR expression on hematopoietic cells is essential for P. chabaudi cell cycle synchronization

IFNγR is widely expressed by hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells; thus, we asked whether the IFNγ-induced effect on parasite synchronization is mediated by hematopoietic or non-hematopoietic tissues. We generated IFNγR−/− and IFNγR+/+ (wild-type, WT) chimeras containing hematopoietic cells from either IFNγR+/+ or IFNγR−/− mice. The Pc cell cycle was unsynchronized in either IFNγR−/− or IFNγR+/+ chimeras containing IFNγR−/− hematopoietic cells; but was synchronized in chimeric mice containing IFNγR+/+ hematopoietic cells (Figure 3A). All IFNγR−/− and IFNγR+/+ chimeras produced high levels of IFNγ when infected with Pc (Figure S3A), indicating that their defect in controlling parasite cell cycle was due to an impairment in IFNγ signaling rather than impaired cytokine production.

Figure 3. IFNγR expression by hematopoietic cells is essential for Pc cell cycle synchronization.

Concavity (C), confidence intervals (within brackets) and p values (in each figure) indicate that (A) opposed to WT->WT (n=8) (top graphs) and WT-> IFNγR−/− (n=8), the different Pc stages are evenly distributed in IFNγR−/−->WT (n=8) and IFNγR−/−->IFNγR−/− (n=8) chimera mice at different time points. Ring: WT->WT C=−1.28 [−1.44, − 1.12] versus IFNγR−/−->WT C=−0.3 [−0.45, −0.14] or WT->IFNγR−/− C=−1.04 [−1.18, −0.91] versus IFNγR−/−-> IFNγR−/− C=−0.14 [−0.28,0.01]; Trophozoite: WT->WT C=0.97 [,0.81,1.12] versus IFNγR−/−->WT C=−0.33 [0.17,0.49] or WT->IFNγR−/− C=−0.85 [0.72,0.98] versus IFNγR−/−-> IFNγR−/− C=0.12 [−.0.01,0.26]; and Schizont: WT->WT C=0.31 [0.23,0.39] versus IFNγR−/−->WT C=−0.03 [−0.11,0.04] or WT->IFNγR−/− C=0.19 [0.13,0.26] versus IFNγR−/−-> IFNγR−/− C=−0.02 [−0.05,0.08]. p values in each figure indicate that there is no difference in parasite synchronization when comparing (B) WT (n=13) versus 3D (UNC93B1 mutant) (n=6), IFNAR−/− (IFNα/β receptor deficient) (n=7), Ig μ-chain−/− (B cell and antibody deficient) (n=6) or ββββ2m−/− (CD8+ T cell deficient) (n=7), respectively; as well as (C) WT mice treated with control isotype (n=8) versus anti-Ly6G (n=8) to deplete neutrophils. Chimera, knockout and depletion experiments are pool of 2 experiments that yielded similar results. Estimates and testing based on multivariate mixed effect model with mouse as a random effect are described in the methods section. Chimeric mice were reconstituted with bone marrow cells from congenic C57BL/6 (CD45.1) or IFNγR−/− (CD45.2) strains and validated by flow cytometric analysis using labeled anti-CD45.1 and anti-CD45.2 antibodies. Neutrophil depletion was validated by flow cytometry using anti-CD11b, anti-Ly6c and anti-Ly6G. Counting of different parasite stages, at day 8 p.i. with Pc, is presented as the average and SEM indicated by shaded areas along the lines. See also Figure S3.

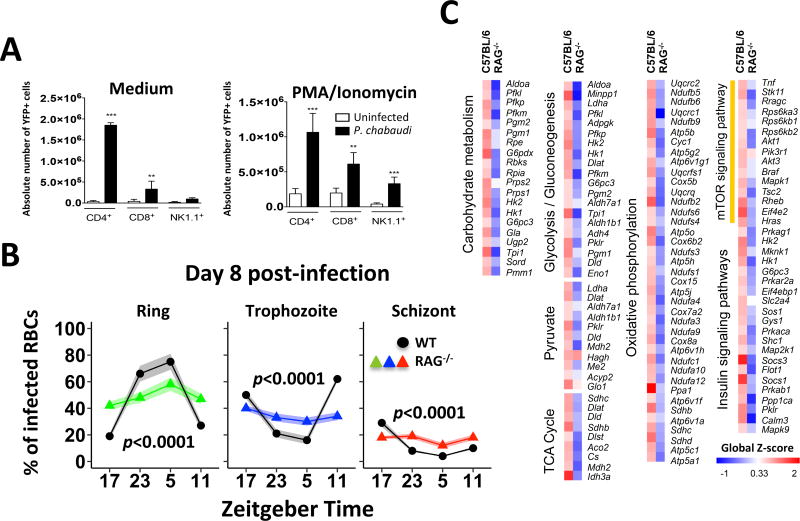

We then evaluated the involvement of different components of the immune system that are relevant in the pathophysiology of Plasmodium infection (Gazzinelli et al., 2014). The UNC93B1 null mutation leads to a functional deficiency in the endosomal TLRs (TLR3/7/9); deletion of either IFNα/β receptor (IFNAR) or Igμ leads to B lymphocyte and antibody deficiency; and deletion of β2-microglobulin leads to CD8+ T lymphocyte deficiency. Pc synchronization was not impacted in mice deficient in these immune components (Figure 3B). In addition, in vivo depletion of neutrophils did not affect parasite cell cycle synchronization within RBCs (Figure 3C and S3B). In contrast, CD4+ T cells are the major source of IFNγ and the Pc cell cycle is unsynchronized in RAG−/− mice that lack both T and B lymphocytes (Figures 4A and 4B). Consistently, the expression of genes involved in energy metabolism and inflammatory responses was not augmented in RAG−/− mice infected with Pc (Figure 4C). Altogether, our results support the hypothesis that hematopoietic cells have a key role in synchronizing the Pc cell cycle, not only because T cells are the major source of IFNγ, but also for mediating IFNγ-induced cellular responses.

Figure 4. Disrupted energy metabolism gene signature and parasite synchronization in Pc-infected RAG-1−/− mice infected.

(A) Splenocytes from uninfected and infected GREAT mice were left unstimulated or stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) plus ionomycin (500 ng/mL) and analyzed by flow cytometry. YFP+ cells were considered as IFNγ producers and data presented as total number of positive cells per spleen. YFP+ CD4+ T, CD8+ T or NK cells from uninfected and Pc-infected mice were analyzed by Student’s unpaired t test with Welch’s correction for analysis of data with parametric distribution. (B) Percentage of infected RBCs containing the ring-form trophozoites (green), mature trophozoites (blue), or schizonts (red) in 13 C57BL/6 (black line) and 7 RAG−/− mice. Concavity measurements, confidence intervals (within brackets) and p values (in each graph) indicate that the different Pc stages are evenly distributed in RAG−/− mice at different time points. Ring: WT C=−1.41 [−1.55, −1.26] versus RAG−/− C=−0.18 [−0.37,0.01]; Trophozoite: WT C=1.01 [0.88, 1.15] versus RAG−/− 0.13 [−0.04, 0.3]; and Schizont: WT C=0.39 [0.32, 0.047] versus RAG−/− 0.05 [−0.05, 0.16]. RAG experiments are pool of 2 experiments that yielded similar results. Estimates and testing based on multivariate mixed effect model (parasitemia) with mouse as a random effect as described in the methods section. (C) Heatmap illustrating differential expression of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism in spleen cells from infected C57BL/6 or RAG−/− mice. The fold increase of each group was calculated by averaging the value of 3 individual infected mice divided by the average value of 3 uninfected control mice. The color scheme represents the global Z-score (A and B). See also Table S2.

TNFR plays a major role in controlling glucose levels and synchronizing the P. chabaudi cell cycle

The liver is the main organ regulating the host peripheral circadian cycle and blood glucose levels after food intake (Sato et al., 2017). Hence, we performed a transcriptome analysis of livers from infected mice at different time points across the circadian cycle and found a number of carbohydrate metabolism and inflammatory genes with up-regulated, down-regulated, oscillated or unchanged expression (Figures 5A and S4). Three out of 19 pathways that were enriched for genes with oscillating expression across the circadian cycle are important in controlling glucose metabolism, i.e., the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARγ), and the insulin resistance pathway, including the TNFα gene (Figure 5B). The gene expression and plasma levels of circulating TNFα in Pc-infected mice peaked at ZT 23 (Figure 5B and 5C, left panel). Notably, TNFα production was impaired in either IFNγR−/− or IFNγ−/− mice infected with Pc (Figure 5C, right panel). Importantly, hypoglycemia was attenuated and synchronization of Pc cell cycle disrupted in TNFR−/− mice (Figure 5D and 5E). We conclude that IFNγ-priming of hematopoietic cells is important for optimal TNFα production, consequent hypoglycemia and parasite synchronization in Pc-infected mice.

Figure 5. TNF receptor mediates hypoglycemia and synchronization of the Pc cell cycle.

(A) Number of genes from carbohydrate metabolism and inflammatory pathways that demonstrate differential expression in the liver of Pc-infected mice over a 24 h period. (B) Heatmap illustrates oscillating expression of genes from AMPK, PPAR and insulin resistance pathways in liver from uninfected (day 0) and Pc-infected (day 8) C57BL/6 (WT) mice at ZT 17, 23, 5 and 11. Arrows indicate key genes [i.e., 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (Pkfb3), PPARγ, and TNFα] involved in regulating glucose metabolism. Data are the average of individual gene expression from 3 infected and 3 uninfected WT mice. (C) Levels of TNFα in sera from mice collected at ZT 17, 23, 5 and 11 on days 0 (uninfected controls), 6 and 8 p.i. with Pc (left panel); and in sera collected at ZT 1 from WT, IFNγR−/−, and IFNγ−/− mice at 0 and 8 days p.i. (right panel). The results are an average of 3–4 mice per group. The mean TNFα levels from uninfected and infected C57BL/6 to IFNγ and IFNγR were compared using the Student’s unpaired t test with Welch’s correction for analysis of data with parametric distribution. (D) The three-way interaction was significant (p=0.04); for Day 8 there was a significant difference in trends over time between infected TNFR−/− (n=14) and infected WT mice (n=23) (p=0.0028). Differences in means of blood glucose levels are statistically significant, when comparing infected IFNγ−/− and infected WT mice at the same time point, as indicated by * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) and ***(p<0.001) indicate. There was no significant difference in trends at Day 0 (p=0.02), when comparing TNFR−/− (n=23) versus WT (n=31). Experiments are pool of 4 experiments that yielded similar results. (E) The percentage of RBCs containing the ring-form trophozoites (green), mature trophozoites (blue), or schizonts (red) in Pc-infected TNFR−/− (n=10) and C57BL6 (n=13, black lines) mice. Concavity measurements, confidence intervals (within brackets) and p values (in each graph) indicate that the different Pc stages are evenly distributed in TNFR−/− mice at different time points. Ring: WT C=−1.41 [−1.55, −1.26] versus TNFR−/− C=−0.13 [−0.26,0.01]; Trophozoite: WT C=1.01 [0.88, 1.15] versus TNFR−/− 0.13 [−0.06, 0.21]; and Schizont: WT C=0.39 [0.32, 0.047] versus TNFR−/− 0.05 [−0.03, 0.13]. Experiments are pool of 3 experiments that yielded similar results. Estimates and testing based on multivariate mixed effect model (parasitemia) with mouse as a random effect as described in the methods section. See also Figure S4, and Tables S3 and S4.

Schizont formation and Plasmodium synchronization is influenced by the schedule of host food intake

From the above results, we hypothesized that IFNγ-dependent/TNFα-induced hypoglycemia is an important determinant of Plasmodium cell cycle timing. Importantly, both physical activity and food intake of infected WT and IFNγ−/− mice, in a regular light cycle, are similar and occur at night (Figures S5A and S5B). Thus, we subjected groups of mice to four different conditions: (i) regular light cycle and food ad libitum; (ii) inverted light cycle and food ad libitum; (iii) regular light cycle and nighttime (active phase) food access; and (iv) regular light cycle and daytime (resting phase) food access. As expected, the reverse light schedule inverted the parasite cell cycle (David et al., 1978). We observed that glucose levels dropped at ZT 23 and were restored at ZT 5, whereas normoglycemia was maintained at ZT 11 and 17 (Figure 6A and S5C). In either light schedule, we observed a higher frequency of ring-form trophozoites at ZT 23 and 5, mature trophozoites at ZT 11 and 17, and schizonts at ZT 17. Importantly, we found that mice fed during the active phase (nighttime) (Figure 6B, upper panel), but not resting phase (daytime) (Figure 6B, bottom panel) behaved similarly to the regular (Figure 6A, upper panel). Hence, parasite cell cycle timing is determined by the daily rhythm of food intake, rather than light schedule.

Figure 6. Inverted light schedule and nighttime diet restriction inverts timing of Pc stages synchronization.

Mice were maintained on a regular light cycle, lights on from 7:00 am (ZT 0) to 7:00 pm (ZT 12), with food access either at nighttime (ZT 12 to 24), daytime access (ZT 0 to 12) or ad libitum. Alternatively, mice were kept on inverted light cycle, lights on from 7:00 pm (ZT 0) to 7:00 am (ZT 12) and food ad libitum. After three weeks, mice were infected with Pc and maintained in the same light/diet regimen. (A) The three-way interaction was significant (p=0.0038); for Day 8 there was a significant difference in trends over time between infected regular light schedule and daytime diet (p<0.001). Differences in means of blood glucose levels are statistically significant, when comparing infected regular light schedule and daytime diet at the same time point, as indicated by ** (p<0.01). The data are from 8–12 mice per group. B) Concavity measurements, confidence intervals (within brackets) and p values (in each graph) indicate that the different Pc stages inverted in WT mice kept in regular light schedule and fed at daytime (n=8) versus mice that received food ad libitum (n=13). Ring: ad libitum C=−1.41 [−1.58, −1.23] versus daytime C=0.94 [0.72,1.17]; Trophozoite: ad libitum C=1.01 [0.85, 1.18] versus daytime −0.66[−0.88, −0.45]; and Schizont: ad libitum C=0.39 [0.27,0.52] versus daytime −0.28 [−0.44, 0.12]. Inverted light schedule and diet restriction are pool of 2 experiments that yielded similar results. Estimates and testing based on multivariate mixed effect model (parasitemia) with mouse as a random effect as described in the methods section. There is no difference in parasite stage distribution, in mice kept in regular light schedule and inverted light schedule receiving food ad libitum (top panel) or regular light schedule with food access only at nighttime. See also Figure S5.

Interference with insulin control and blood glucose levels alters P. chabaudi cell cycle synchronization

Our studies showed a positive correlation between increased glucose levels in the blood and Pc schizogony. To investigate this connection, we evaluated: (i) parasite synchronization in diabetic mice; and (ii) the effect of food- or glucose-intake on schizogony after 18 h fasting. To evaluate the influence of insulin control on parasite synchronization, we treated C57BL/6 mice with streptozotocin to destroy their pancreatic β cells. As expected, chemically-induced diabetic mice exhibited extremely high levels of circulating glucose at all ZT times (Figure S6). Consistent with our hypothesis, diabetic mice had a high frequency of all parasite stages at ZT 23, 5, 11 and 17 (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Synchronization of Pc with host circadian rhythm is disrupted in diabetic mice.

(A) Wild-type mice were treated with streptozotocin to induce diabetes and then infected with Pc. Glucose levels (top panels) as well as parasite counts (bottom panels) were evaluated at 8 days p.i. Data are from 7 to 8 mice per group. In parallel experiments, mice were given food access only from ZT 0 to 6 for 10 days, infected with Pc, and kept under the same diet schedule. On day 8 p.i., one group of mice received (B) food and another group received (C) glucose in the water from ZT 0 to 6. The three-way interaction difference in trends over time were significant for (A) diabetic mice (p<0.0001 and not significant p>0.05), (B) mice that received diet (p=0.0088 and p<0.0001), or (C) glucose (p<0.0001and p<0.0001) in the day 8 post-infection. Differences in means of blood glucose levels are statistically significant, when comparing infected diabetic mice, as well as mice that receive diet or glucose to the WT that received food ad libitum at the same time point, as indicated by *** (p<0.001). The data are from 8–12 mice per group. (B) Red and (C) blue arrows indicate the time that diet and glucose access was initiated. Concavity measurements, confidence intervals (within brackets) and p values (in each graph) indicate that the different Pc stages are no longer synchronized in diabetic mice (n=7). Ring: non-diabetic C=−1.41 [−1.53, −1.28] versus diabetic C=0.05 [−0.14,0.23]; Trophozoite: ad libitum C=1.01 [0.89, 1.14] versus daytime −0.07[−0.25, 0.11]; and Schizont: ad libitum C=0.39 [0.32,0.46] versus daytime −0.02 [−0.8, −0.25]. Food restriction for 18 h followed by diet or glucose ingestion from ZT 0 to ZT 6 on day 8 post-infection inverted parasite cell cycle. Schizont: ad libitum C=0.39 [0.27,0.52] versus food access −0.18 [−0.32, 0.04] or glucose access −0.19 [−0.29, −0.09]. Diabetic mice and diet restriction are pool of 2 experiments that yielded similar results. Estimates and testing based on mixed effect model (glucose) or multivariate mixed effect model (parasitemia) with mouse as a random effect are described in the methods section. Individual levels of glucose are shown in Figure S6.

Finally, food intake was allowed only from ZT 0 to 6 for a week. Mice were then infected with Pc and kept on the same diet schedule. On day 8 post-infection (p.i.), a group of mice received regular diet (Figure 7B) and another group of mice received glucose in the drinking water (and not regular diet) (Figure 7C) from ZT 0 to 6. In both groups, the frequency of schizonts increased at ZT 5, indicating that schizogony occurred during the food- or glucose-intake period. Thus, these results support the hypothesis that glucose availability, rather than light schedule, regulate synchronization of Pc cell cycle by promoting schizogony.

DISCUSSION

Here, we investigated whether host inflammatory responses influence the synchrony of Pc blood stages. We found that leukocytes primed with IFNγ during Plasmodium infection display increased expression of glucose metabolism and pro-inflammatory genes. Importantly, a high frequency of non-proliferative trophozoite forms associated with TNFα-induced hypoglycemia, whereas Pc replication (schizogony) occurs during host food intake. Hence, we propose that by regulating blood glucose levels, the daily rhythms of TNFα expression and food intake influence the timing of schizogony and the synchrony of Pc blood stages with the host circadian cycle (graphic abstract).

Dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils are highly activated and play an important role in host resistance to Plasmodium infection and the pathogenesis of malaria (Gazzinelli et al., 2014; Stevenson and Riley, 2004). The underlying hypothesis is that RBCs carry synchronous schizonts and upon bursting release parasite and RBC components, such as glycosylphosphatidylinositol, hemozoin, RNA, DNA, heme, and uric acid (Gazzinelli et al., 2014) that activate TLRs (Parroche et al., 2007), inflammasomes (Ataide et al., 2014; Kalantari et al., 2014; Shio et al., 2009), and cytosolic nucleic acid sensors (Sharma et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2014) culminating in a pro-inflammatory cytokine storm. Recent studies indicate that a shift in energy phenotype is critical for the pro-inflammatory and effector functions of immune cells (Mills et al., 2017). Here, we report that transcriptional signatures of mTOR, insulin pathways and glucose metabolism are all enriched in leukocytes from P. falciparum-infected patients and Pc-infected mice. While endogenous IFNγ was critical in up-regulating glucose metabolism and pro-inflammatory genes in leukocytes, TNFα appears to have a key role in controlling blood glucose levels.

The liver is a central organ in regulating glucose metabolism and peripheral circadian cycle (Eckel-Mahan et al., 2013). Importantly, transcriptional gene signatures relevant to glucose metabolism were enriched in the liver of Pc-infected mice. Liver expression of genes from AMPK, PPAR and insulin resistance pathways oscillated over 24 h, peaking around ZT 23 to 5. AMPK is a cellular energy sensor that promotes glucose uptake and the target of the hypoglycemic drug metformin (Zhang et al., 2009), while PPARγ is a nuclear receptor that enhances sensitivity for insulin and is the molecular target for thiazolidinediones (glitazones) used to treat type 2 diabetes (Picard and Auwerx, 2002). Among the genes in the insulin resistance pathway, TNFα caught our attention. TNFα stimulates glucose uptake and metabolism in host cells (Sakurai et al., 1996; Spolarics et al., 1991), induces hypoglycemia in sepsis models (Vogel et al., 1991), and plays a key role in the pathophysiology of malaria (Elased and Playfair, 1994; Lou et al., 2001). Importantly, the peak of TNFα expression in Pc-infected mice coincides with transient hypoglycemia at ZT 23. Furthermore, hypoglycemia was attenuated and synchrony of Pc stages was disrupted in TNFR−/− mice.

Insulin is the master regulator of glucose metabolism and hyperinsulinemia associated with hypoglycemia reported in a malaria mouse model (Elased and Playfair, 1994). We found an enriched transcriptional signature for insulin responsive genes and the mTOR pathway in the liver. Importantly, treatment with rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, leads to insulin resistance and enhances parasitemia in P. berghei-infected mice (Gordon et al., 2015). Crosstalk among AMPK, PPARγ, TNFα and mTOR pathways has been described (Inoki et al., 2012; Ozes et al., 2001; Ye, 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). Future studies should help to pinpoint the key elements of this intricate network of signaling and metabolic pathways that regulate glucose metabolism during Plasmodium infection.

Earlier studies proposed that intermittent fever during malaria limits P. falciparum growth and results in parasite synchronization (Kwiatkowski, 1989). However, acute infection in the Pc mouse model is associated with torpor and low body temperatures, rather than high fever (Li et al., 2003). In addition, melatonin promotes specific gene signatures and P. falciparum differentiation in vitro (Lima et al., 2016). Importantly, the switch in light schedule leads to an inversion of parasite cell cycle and treatment with melatonin stimulates Pc schizogony in mice (David et al., 1978; Hotta et al., 2000). However, by keeping the regular light schedule and forcing food intake during daytime (resting phase), we inverted the Pc cell cycle. Moreover, synchronization of Pc is disrupted in diabetic mice, despite the light schedule. Hence, Pc schizogony seems to occur in conditions where blood glucose levels are higher, independent of the light schedule.

Our findings are supported by the finding that schedule of food intake is responsible for the timing of parasite differentiation and schizogony (Prior et al., 2018). It was also observed that the systemic pro-inflammatory response oscillate during the 24 h period, following the time of schizogony. This leads to the question whether synchrony of Pc stages is solely determined by time of schizogony and whether the immune responses are involved. Importantly, without immunological pressure the P. falciparum cell cycle is not synchronized in vitro (Lambros and Vanderberg, 1979). Our results with IFNγ−/− and TNFR−/− mice suggest that these cytokines influence the process of parasite synchronization. While there is no evidence that IFNγ and TNFα act directly on Plasmodium parasites, both cytokines have pleiotropic effects, both on hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells, and thus, we can not exclude that different mechanisms maybe contributing to the process of parasite synchronization (Reece et al., 2017). Our results indicate that B lymphocytes/Immunoglobulins, CD8 T cells, nucleic acid sensing TLRs, IFNα/β receptor and neutrophils are not involved. Nevertheless, similar to P. falciparum, Pc schizonts adhere to endothelial cells and are sequestered in different organs (Stephens et al., 2012). Hence, cytokine-induced expression of adhesion molecules may contribute to synchronization of Pc stages in the bloodstream (Ockenhouse et al., 1992). However, in WT mice the higher frequency of ring-forms and mature trophozoites that are not adherent, are seen at different time-points. Hence, we hypothesize that during IFNγ/TNF-induced hypoglycemia ring-forms (G1 phase) transform into mature trophozoites (S phase) preparing for schizogony (mitosis) that is triggered by nutrient availability during host food intake. In contrast, in the IFNγ−/−, TNFR−/− or diabetic mice there is no arrest on G1/S phase and parasites replicate across the circadian cycle.

Importantly, Plasmodium spp. lack key enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis and the parasite blood stages are primarily dependent on sugar uptake from host cells to support intracellular survival and growth (Salcedo-Sora et al., 2014; Srivastava et al., 2016). Hence, hypoglycemia may result in decreased glucose uptake by RBCs and limited availability of an important energy source for parasite replication. Alternatively, a recent study described a novel Plasmodium nutrient sensor that is activated under energy deficiency and switches off parasite proliferation. The authors suggest that increased levels of circulating glucose suppresses this nutrient sensing signaling cascade and allows parasite proliferation (Mancio-Silva et al., 2017).

We hypothesize that the importance of pro-inflammatory response, glucose metabolism and food intake in regulating the timing of schizogony may be applicable to other Plasmodium spp., including those that cause human disease. Indeed, microarray analyses shows an enrichment of glycolytic and pro-inflammatory pathways in leukocytes from hosts infected by P. falciparum (Ockenhouse et al., 2006), P. berghei (Sexton et al., 2004), and P. yoelii (Schaecher et al., 2005). Furthermore, food restriction limits parasite growth in P. berghei (Mejia et al., 2015) and P. yoelii (Mancio-Silva et al., 2017) mouse models. Importantly, earlier studies indicate that the blood stages of various Plasmodium spp. synchronize during infection in mice (e.g., Pc, P. yoelii and P. berghei), non-human primates (e.g., P. knowlesi), and humans (e.g., P. falciparum and P. vivax) (Gautret et al., 1994; Hawking, 1970; Mons et al., 1985), although the cell cycle of virulent parasites may become unsynchronized (Kwiatkowski and Nowak, 1991).

P. falciparum and P. vivax infections in humans cycle with intervals between 24 and 48 h (Mideo et al., 2013). It is possible that Plasmodium differentiation and replication take longer than the rodent Plasmodium spp. Intriguingly, re-feeding hospitalized patients in Africa often results in malaria attacks (Murray et al., 1975). In addition, severe malaria in children is associated with insulin resistance as indicated by delayed glucose uptake (Zijlmans et al., 2008). Furthermore, a large case-control study in Ghana concluded that diabetic patients have an increased risk of P. falciparum infection (Danquah et al., 2010). These clinical reports support the hypothesis that parasite replication is augmented under conditions of elevated blood glucose levels.

In conclusion, we propose that the release of parasite components from bursting RBCs carrying schizonts trigger IFNγ-primed phagocytes to transiently produce TNFα. While TNFα-induced hypoglycemia limit parasite replication, Plasmodium takes advantage of host food intake and nutrient availability to proliferate. We recognize that Plasmodium synchronization is a complex phenomenon that involves multiple components of vertebrate host and parasite. Nevertheless, our findings enlighten a fundamental question related to Plasmodium biology in the vertebrate host and pathogenesis of malaria and may provide insights for therapeutic interventions to this devastating disease.

STAR*METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Additional information or requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Ricardo T. Gazzinelli (ricardo.gazzinelli@umassmed.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Ethics Statement

The study with malaria patients and healthy donors was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) from the Research Center of Tropical Medicine (CEP/CEPEM 096/09), the Brazilian National Committee of Research (CONEP/Ministry of Health – 15653), and the Institutional Research Board from the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS) (IRB-ID11116). Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects (Plasmodium-infected patients and healthy donors) before enrollment. All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science (AALAS), the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Brazilian National Council of Animal Experimentation (http://www.cobea.org.br/), and Federal Law 11.794 (October 8, 2008). All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UMMS (ID 2371-15-5) and the Council of Animal Experimentation from Fiocruz and Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (CEUA protocol 38/10-3).

Malaria patients and healthy controls

Patients with acute febrile malaria were treated in the outpatient clinic at the Tropical Medicine Research Center in Porto Velho, Brazil. PBMCs from three males and three females infected with P. falciparum were cultured for cytokine measurements (age varying from 28–60). Two males and three females non-infected subjects living in Porto Velho were included as controls (age varying from 26–59). In the microarray study, ten males and four females with age varying from 19 to 48 years old that were naturally infected with P. falciparum received a single dose of mefloquine. Up to 100 mL of blood was drawn immediately after confirmation and differentiation of Plasmodium infection by a standard peripheral smear and 30–40 days after therapy initiation and confirmed parasitological cure by PCR.

Experimental malaria model

Wild type C57BL/6J and fully backcrossed IFNγ−/−, RAG1−/−, Ig-μ-chain−/− (B cell deficient), IFNAR−/− (IFNα/β receptor deficient), β2m−/− (CD8 deficient mice), TNFR−/− (TNFR p55/p75 chains double knockout mice) and GREAT (IFNγ YFP-reporter) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). UNC93B1 (3D) (TLR3, TLR7, TLR9, TLR11, TLR12 deficient) mutant mice were kindly provided by Dr. Bruce Beutler. Knockout, mutant and wild-type mice were bred, reared, and maintained for experiments in micro-isolators in a maximum number of four mice per cage, receiving sterile water and autoclave food at animal house from either Oswaldo Cruz Foundation or University of Massachusetts Medical School. We used male and female mice between 8–12 weeks of age for the experiments. Unless otherwise specified (see below Inverted light cycle and diet restriction), all mice received food ad libitum and were kept under regular light schedule, i.e., lights on from 7 am to 7pm and lights off from 7 pm to 7 am. For generating chimera mice, either recipient C57BL/6 (IFNγR+/+) or IFNγR−/− mice received two doses of body irradiation (5.5 Gy) 3 h apart. Mice were reconstituted intravenously with 5 million bone marrow cells prepared from donor tibial and femoral bones by flushing with phosphate-buffered saline. Irradiated and reconstituted mice received 150 mg/ml sulfamethoxazole and 30 mg/ml N-trimethoprim in their drinking water for two weeks. Next, they were switched to sterile drinking water to ensure that the antibiotic treatment would not affect the experimental infection with Pc. Mice were used for experimental infection or for analysis of chimerism eight weeks after transplant. Animals showed full reconstitution of lymphoid and myeloid cell populations as determined by flow cytometric analysis.

The Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS strain (Pc) was used for experimental infections (Falanga et al., 1987; Ataide et al., 2014). Briefly, Pc was maintained in C57BL/6 mice by serial passages once a week up to ten times. For experimental infection, mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 105 infected RBCs. The percentage of RBCs containing ring-form trophozoites (small or delicate, thin ring of cytoplasm with a vacuole and a prominent chromatin dot), mature trophozoites (one or two nuclei with an enlarged cytoplasm), or schizonts (parasite with multiple nuclei) (Figures 2 and S2A) were determined in the blood from acutely infected mice, at eight days p.i. during the first peak of parasitemia. Blood parasite stages were counted in a blood smear stained with Giemsa at ZT 17, 23, 5, and 11. In some experiments, whole blood for plasma collection and cytokine measurements were collected at the same time points.

METHODS DETAILS

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) cultures

PBMCs were isolated from whole blood using Ficoll-Paque Plus gradient. Cells were then plated into 96-well culture plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well in RPMI containing 10% FCS and 0.1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Supernatants were collected 24 h after stimulation with either LPS or R848 and used to determine cytokine levels by cytometric bead array (CBA) for IL-1β, IL-10, IL-12p70, and TNFα.

Food intake and physical activity

Mouse food intake and physical activity were assessed for 3 days prior to infection and at days 6, 7 and 8 post-infection with Pc using metabolic cages (TSE Systems, Chesterfield, MO) located at the National Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (MMPC) at UMASS Medical School. Mice were housed under controlled temperature and lighting, with food and water ad libitum. Monitoring for food intake and physical activity was fully automated using the TSE Systems LabMaster platform. LabMaster cages allowed the use of bedding, thus, minimizing any animal anxiety during the experimental period.

Inverted light cycle and diet restriction

In most experiments, mice were fed ad libitum and kept on a regular light cycle with lights on from 7:00 am (ZT 0) to 7:00 pm (ZT 12) and lights off from 7:00 pm (ZT 12) to 7:00 am (ZT 24). In two experiments, mice were kept on an inverted light cycle with lights on from 7:00 pm (ZT 0) to 7:00 am (ZT 12) and lights off from 7:00 am (ZT 12) to 7:00 pm (ZT 24). In two other experiments, mice were kept on a regular light cycle, but had their diet removed either from ZT 12 to 24 (daytime access) or from ZT 0 to 12 (nighttime access). Lastly, in two experiments mice were given access to food only from ZT 0 to 6. At day 8 of infection one group of uninfected and one group of infected mice received glucose (50%) in the drinking water from ZT 0 to 6, instead of their regular diet. In all cases, mice were subjected to different light or diet schedules for 3–4 weeks before infection with Pc, and kept on the same light or diet schedule until experimental data were collected.

Treatment with streptozotocin

To induce type 1 diabetes, seven-week-old C57BL/6 mice were treated i.p. daily for five consecutive days with streptozotocin (40 mg/Kg) and rested for three days (Emanueli et al., 2004). Mice were considered diabetic if they had a fasting glucose level > 250 mg/dL.

Glucose measurement

Blood glucose levels were measured with an Accu-chek® glucometer at ZT 17, 23, 5, and 11 at 0 (uninfected controls) and 8 days post-infection with Pc.

Neutrophil depletion

In vivo neutrophil depletion was performed by administering i.p. the anti-Ly6G antibody (500 µg/dose) or an isotype control (500 µg/dose). Mice received the injections every other day, starting 1 day before infection. Neutrophil depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis of blood cells, using FSC-A/SSC-A and the monoclonal antibodies specific for CD11b (PECy7), Ly6C (eFluor 450) and Ly6G (FITC). Samples were acquired using a LSRII (BD Biosciences) cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo software.

Splenocyte cultures

Spleens from uninfected controls and C57BL/6 mice at 8 days post-infection with Pc were harvested, suspended in RPMI medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum at 2.5×106 cells/mL. Cells were cultured with either medium alone, or in the presence of CpG or R848 for 48 hours and the supernatants stored at −20 °C for measurement of cytokines. Mouse cytokines were quantified in supernatants of splenocyte cultures from control and Pc-infected mice by CBA (IL6, IL-10, TNFα, and MCP-1). Mouse IFNγ was quantified by ELISA. The main IFNγ source in spleen of Pc-infected mice was identified by flow cytometry analysis, using splenocytes from GREAT (IFNγ YFP-reporter) mice. Briefly, spleen cells were either stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) plus ionomycin (500 ng/mL) or left unstimulated for 4 h in culture containing brefeldin A and analyzed by flow cytometry gated on CD4+, CD8+ or NK1.1+ cells. FSC-A/SSC-A and the monoclonal antibodies specific for CD3 (FITC, clone 145-2C11), CD4 (APC, clone RM4-5), CD8 (APC-Cy7, clone 53-6.7) and NK1.1 (BV421, clone PK136) were used to gate YFP+ cells. Samples were acquired using a LSRII (BD Biosciences) cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo software.

Human and mouse microarray experiments

Global gene expression of PBMCs from naturally infected malaria patients was analyzed employing the Illumina HumanWG-6 v2.0 method (~47,000 transcripts/microchip) (Franklin et al., 2009). Each patient served as his/her own control. Fold increase of gene expression was calculated by using PBMCs from the same patient before and 30–40 days after documented curative treatment. Sample filtering, normalization, and averaging were conducted with BASE (Bio-Array Software Environment) (https://base.thep.lu.se) and log transformed (log2) (Vallon-Christersson et al., 2009). Genes were filtered to include those with a signal greater than the average from the negative controls in at least one of the samples with a detection p<0.01. For mouse experiments, we used splenocytes from three C57BL/6, three IFNγ−/− and three RAG−/− mice at zero (uninfected) and at six days p.i. with Pc. Gene expression was assessed using a gene chip from Affymetrix (23,000 transcripts). The expression value for each gene was determined by calculating the average of differences in intensity (perfect match intensity – mismatch intensity) between its probe pairs.

Mouse RNA-Seq

RNA-seq was performed in biological replicates (3 mice per group). Liver samples were collected from C57BL/6 mice at different time points: ZT 17, ZT 23, ZT 5 and ZT 11 from mice at day 8 post-infection with Pc or uninfected controls. RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the TruSeq® Stranded mRNA Kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, poly-A containing mRNA molecules were purified using poly-T oligo attached magnetic beads and fragmented using divalent cations. The RNA fragments were transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), followed by second strand cDNA synthesis using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. Finally, cDNA fragments then have the addition of a single 'A' base and subsequent ligation of the adapter. The products were then purified and enriched by PCR using paired-end primers (Illumina) for 15 cycles to create the final cDNA library. The library quality was verified by fragmentation analysis (Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer) and submitted for sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq 500 (Bauer Core Facility Harvard University).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Microarray analysis

For both human and mouse experiments, tables containing the expression values of all genes passing the above mentioned filters were produced and imported into GenePattern for further analysis (https://software.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern). To identify genes that can discriminate between infected and treated patients, or infected and uninfected mice of wild-type or IFNγ−/− or RAG-1−/− genotypes, respectively, we used the Comparative Marker Selection suite parameterized with two-sided t test and 1000 permutations to compute the significance of marker genes. The permutation method is advantageous because it does not assume parametric distribution of the expression values. The Benjamini and Hochberg correction for multiple testing was used for computing the false discovery rate (FDR). Differences in gene expression between the two conditions were considered significant when p<0.01 and fold change ≥1.5. Heatmaps were produced with the HeatMapViewer module of GenePattern with a globally normalized color scheme. Functional enrichment analysis of the lists of differentially expressed genes disclosed in each pair wise comparison was done with the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v6.8 at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), NIH (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp). In addition, for Figure 2B, GSEA was run using "before" vs "treated" log2 fold-change as rank and Reactome pathways as gene sets (default GSEA settings, 1,000 permutations) (https://software.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern). Gene sets with p<0.05 are shown ordered by NES (Normalized Enrichment Score). Correlations between the average log2 fold change of three uninfected and three infected mice of the same genotype were tested with Pearson’s or Spearman’s tests for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively, using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). A non-significant correlation (p≥0.05) denotes genotype influence on the pathway. A Principal Variance Component Analysis indicated that main variable influencing differential gene expression was the P. falciparum infection and not sex - https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/3.7/bioc/vignettes/pvca/inst/doc/pvca.pdf.

RNA-Seq analysis

Reads previously trimmed with Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014) were mapped to the Genome Reference Consortium Mouse Build 38 patch release 5 (GRCm38.p5) using STAR aligner (Dobin et al., 2013) and the Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) values were calculated with CUFFLINKS (Trapnell et al., 2012). Data were then analyzed with the software Short Time-series Expression Miner (STEM, version 1.3.11) (Ernst and Bar-Joseph, 2006) to identify genes with variable expression patterns along the period of 24h sampled at each 6 hours. STEM was parameterized as follows: fold change ≥ 1.5 between any pair of time points and p≤0.05 in Bonferroni’s test. The minimum correlation allowed between replicates was 0.9. The maximal correlation between profiles was 0.7 to the functions Modeling Profiles and Clustering Profiles. Data from control and infected groups were analyzed separately with STEM and results were merged afterwards. Genes passing STEM’s filters were analyzed for pathway enrichment with DAVID and those filtered by STEM were tested for differential expression due to infection using Genepattern as described above for the study with microarrays (fold change ≥1.5; FDR ≤0.01). Genes with stable expression in a 24 hours period, which were differentially expressed in response to the infection were then analyzed for pathway enrichment with EASE version 2.0 (Hosack et al., 2003), the standalone version of DAVID.

Statistical analysis

For the estimation and comparisons of mean glucose over time, a mixed effect linear regression model was fit with mouse as the random effect and group, day and time as fixed effects. The primary analysis of interest was the comparison of glucose trends in the infected mice groups (Day 8). Varying patterns were hypothesized, so time was used in the model as a categorical variable: 0, 6, 12 and 18 hours. The full model was estimated including all two way and three way interactions of group, day and time. The three-way interaction was tested using a likelihood ratio test comparing the models with and without the three-way interaction term. If the three-way interaction was significant this was interpreted as different trends over time by day and group. The primary estimates of interest are Day 8, so a mixed effects model was fit to estimate and compare mean glucose at Day 8 between the comparator groups. Linear combinations of coefficients from the model provided estimates of mean glucose and mean glucose changes in each time interval. Estimates, confidence intervals and tests accounted for the correlation of measures within mouse over time. All models were fit using Stata 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) mixed model function (mixed).

For the estimation and comparisons of percent parasitemia in each stage, a mixed effect multivariate linear regression model was fit since there are multiple outcomes (stages) being estimated (ring, trophozoite and schizont). The three stages sum to 100% so the model fit ring and trophozoite as a function of group and time with mouse as a random effect and estimates accounting for the covariance of outcome measures. The schizont estimates and confidence intervals are derived from the two other stages since the three total to 100%. For parasitemia outcomes a specific pattern was hypothesized the comparisons. The control group outcomes (for example wild type) would show strong positive or negative concavity while some of the knockout mice would have little to no change over time and thus be ‘flat’ or have little to no concavity. We used time as a quadratic function in the model and twice the coefficient of the squared term from the model estimated concavity. It was noted that estimated means at each time point using the quadratic function provided similar estimates to a model using time as a categorical variable. The primary estimate of interest was decrease in concavity and an estimated low concavity in the comparator groups. The model included a two-way interaction of group and time and the interaction was tested using a likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without the two- way interaction. A significant interaction indicated differences in the overall trend over time between groups. Estimated means and mean change in the percent stages were derived from the linear combination of coefficients in the models. Of primary interest was the estimation of and comparison of concavity in each group. For concavity an increase – larger positive or negative concavity - indicates the same pattern of parasitemia cycling so only decrease indicates a change in pattern so the hypotheses tested were HO: |concavityKO| ≥ |concavityWT| vs HA: |concavityKO| < |concavityWT|. The one-sided p-values are reported for all comparisons. Estimates, confidence intervals and tests accounted for the correlation of measures within mouse over time. All models were fit using Stata 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) generalized structural equation model function (gsem).

In addition, we used GraphPad Prism 7.0 software for cytokine Bead Array analyses were performed using Mann-Whitney test for non-parametric data, which indicated that there is no statistical difference on cytokine response, when comparing P. falciparum-infected male and female patients. TNFα levels as well as frequency of YFP+ cells in T cell and NK subsets were compared using Student unpaired t test with Welch’s correction for parametric data.

The numbers (n) of patients and healthy donors (Figure 1) from whom we collected PBMCs as well as from mice that we collected blood, spleens and livers for the different experiments presented in this manuscript are indicated in the Figure legends. All experiments were performed with individual and not pooled samples.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Microarray data

Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbin.lm.nih.gov/gds/) accession numbers are GSE35083 for mouse and GSE15221 for human microarrays. See also Tables S1 and S2.

RNA Seq data

GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE109908) accession number is GSE109908. See also Tables S3 and S4.

Software Please se Key Resources Table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8) | BioXCell | Cat# BE0075-1 |

| Isotype control (clone LTF-2) | BioXCell | Cat# BP0090 |

| Anti-CD11b-PECy7 (clone M1/70) | eBioscience | Cat# 25-0112-82 |

| Anti-Ly6C-eFluor 450 (clone HK1.4) | eBioscience | Cat# 48-5932-82 |

| Anti-Ly6G-FITC (clone 1A8) | eBioscience | Cat# 11-9668-82 |

| Anti-CD3-FITC (clone 145-2C11) | eBioscience | Cat# 11-0031-82 |

| Anti-CD4-APC (clone RM4-5) | eBioscience | Cat# 17-0042-82 |

| Anti-CD8-APC-Cy7 (clone 53-6.7) | eBioscience | Cat# 557654 |

| Anti-CD45.2 V500 (clone 104) | BD bioscience | Cat# 5562129 |

| Anti-CD45.1 PE (clone A20) | BD bioscience | Cat# 12-0453-82 |

| Anti-NK1.1-BV421 (clone PK136) | eBioscience | Cat# 562921 |

| Parasite, Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Plasmodium chabaudichabaudi AS strain | Dr. D’Imperio-LimaUniversidade de São Paulo; Institute Pasteur; Falanga et al., 1989 | N/A |

| Biological Samples | ||

| None | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Recombinant IFNγ | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# I4777 |

| LPS O55:B55 from E. coli | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# L2880 |

| R848 | Invivogen | Cat# TLRL-R848-5 |

| Streptozotocin | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# 50130 |

| Fetal Calf Serum from HyClone | GE Bioscience | Cat# SH30910-03 |

| Penicillin and Streptomycin | Corning | Cat# 30002-CI |

| Anhydrous D-Glucose | Dinamica | Cat# 363043 |

| Anhydrous D-(+)-glucose (99.5%) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# G8270 |

| Giemsa | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# SLBQ0143V |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Mouse inflammatory cytokines Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 552364 |

| Human inflammatory cytokines (CBA) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 551811 |

| Mouse IFNγ ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat# 88-7314-77 |

| Mouse microarrays | Affymetrix | Cat# 901168 |

| Human microarrays | Illumina | Cat# BD-25-113 |

| Life and Dead/FACS | ThermoFisher | Cat# L34957 |

| Accu-Chek Meter | Roche | Cat# GC01918400 |

| Accu-Chek Test Strips | Roche | Cat# 06656757 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Human PBMC Microarray (raw data and analysis) | This paper | GSE15221 Figs 1 and S1; Table S1 |

| Mouse Spleen Microarray (raw data and analysis) | This paper | GSE35083 Figs 2, 4, and S2; Table S2 |

| Mouse Liver RNA-Seq | This paper | GSE109908 Fig S4; Table S3 and S4 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| None | ||

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C57BL/6J | Jackson Lab | JAX 000664 |

| IFNγ−/− (C.129S7(B6)-Ifngtm1Ts/J) | Jackson Lab | JAX002286 |

| IFNγR−/− | Jackson Lab | JAX003288 |

| RAG1−/− (C.129S7(B6)-Rag1tm1Mom/J) | Jackson Lab | JAX003145 |

| Ig-μ-chain−/− (B6.129S2-Ighmtm1Cgn/J) | Jackson Lab | JAX002288 |

| IFNα/βR−/− (B6.129S2-Ifnar1tm1Agt/Mmjax) | Jackson Lab | JAX32045 |

| β2m−/−(B6.129P2-B2mtm1Unc/J) | Jackson Lab | JAX002087 |

| TNFR p55−/−/p75−/−(B6.129S-Tnfrsf1atm1ImxTnfrsf1btm1Imx/J) | Jackson Lab | JAX003243 |

| IL-1R−/−(B6.129S7-Il1r1tm1Imx/J) | Jackson Lab | JAX003245 |

| GREAT (B6.129S4-Ifngtm3.1Lky/J) | Jackson Lab | JAX017581 |

| UNC93B mutant | Beutler’s Lab | 3D |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| UnmethylatedCpG oligonucleotide B344 TCGACGTTTGGATCGGT | Bartolomeu et al., 2009; Alpha DNA | 292153 (synthesis #) |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| None | ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| FlowJo | FlowJo | http://www.flowjo.com/ |

| Excel | Microsoft | http://www.products.office.com/en-us/excel |

| GraphPad Prism 7.0 software | GraphPad Software | http://www.graphpad.com/scientificsoftware/prism/ |

| The R project for statistical computing | R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| BASE (Bio-Array Software Environment) | Johan Vallon-Christersson et al., 2009. | http://base.thep.lu.se/ |

| GenePattern | University of California and Broad Institute | https://software.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern |

| Comparative Marker Selection suite | University of California and Broad Institute | https://software.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern |

| GSEA | University of California and Broad Institute | https://software.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/genepattern |

| Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v6.8 | NIAID/NIH | https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp |

| Trimmomatic | Bolger et al., 2014. | http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic |

| CUFFLINKS | Trapnell et al., 2012. | http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/ |

| STAR aligner | Dobin et al., 2013. | STAR aligner |

| Short Time-series Expression Miner (STEM) | Ernst et al., 2006. | Short Time-series Expression Miner (STEM) |

| EASE | Douglas et al., 2003. | EASE |

| Principal Variance Component Analysis(PVCA) method | Bioconductor | https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/3.7/bioc/vignettes/pvca/inst/doc/pvca.pdf |

| Stata 15 | StataCorp, College Station, TX | https://www.stata.com/company/ |

| Other | ||

| None | ||

Supplementary Material

Table S1 – Names of human genes included in the heatmap, Related to Figure 1.

Table S2 – Gene Symbol, description and average of log2 Fold Change expression of mouse genes from spleen of infected versus control mice from the same genotype, Related to Figures 2 and 4.

Table S3 – Symbol, description and average expression* (log2 Fold Change, FC) of liver genes that present constant values across the circadian cycle and belong to enriched Kegg pathways, Related to Figure 5.

Table S4 – Symbol, description and average* fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) of liver genes that exhibited variable expression across the circadian cycle and belong to enriched Kegg pathways, Related to Figure 5.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Carbohydrate metabolism genes are induced in leukocytes from malaria patients.

Glucose metabolism and TNFα gene expression parallel circadian rhythm of infected mice

P. chabaudi (Pc) cell cycle is arrested during TNFα-induced rhythmic hypoglycemia

Inverted light schedule and nighttime diet restriction inverts Pc synchronization

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Weaver for helpful discussions and Prof. Sarah Reece, Dr. Kim Prior and a third anonymous reviewer for constructive critiques. We are grateful to Dr. Danielle Durso for preparing figures and submitting RNASeq and microarray data to NCBI and to Melanie Trombly for comments and edition of the final version of the manuscript. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01NS098747, R01AI079293, U19AI089681, R21AI131632 and 5U2C-DK093000), a Brazilian National Institute of Science and Technology for Vaccines (INCT/CNPq), Fundação de Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (465293/2014-0), and Fundação de Amparo de Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (2016/23618-8).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS Conceptualization, I.C.H. and R.T.G.; Methodology, I.C.H., P.A.A., R.T.G.; Formal analysis, H.N., R.S.C., G.R. and R.T.G.; Investigation, I.C.H., P.A.A. and N.H.S.; Writing – Original Draft, I.C.H. and R.T.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, I.C.H., D.T.G. and R.T.G.; Funding Acquisition, R.T.G. and D.T.G; Resources, R.T.G. and D.T.G.; Supervision, R.T.G.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Isabella Cristina Hirako, Email: hirako@minas.fiocruz.br.

Patrícia Aparecida Assis, Email: patricia.assis@umassmed.edu.

Natália Satchiko Hojo-Souza, Email: nataliasatchiko@gmail.com.

George Reed, Email: george.reed@umassmed.edu.

Helder Nakaya, Email: douglas.golenbock@umassmed.edu.

Douglas Taylor Golenbock, Email: hnakaya@gmail.com.

Roney Santos Coimbra, Email: roney.s.coimbra@minas.fiocruz.br.

Ricardo Tostes Gazzinelli, Email: ricardo.gazzinelli@umassmed.edu.

References

- Antonelli LR, Leoratti FM, Costa PA, Rocha BC, Diniz SQ, Tada MS, Pereira DB, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Golenbock DT, Goncalves R, et al. The CD14+CD16+ inflammatory monocyte subset displays increased mitochondrial activity and effector function during acute Plasmodium vivax malaria. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004393. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataide MA, Andrade WA, Zamboni DS, Wang D, Souza Mdo C, Franklin BS, Elian S, Martins FS, Pereira D, Reed G, et al. Malaria-Induced NLRP12/NLRP3-Dependent Caspase-1 Activation Mediates Inflammation and Hypersensitivity to Bacterial Superinfection. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1003885. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomeu DC, Ropert C, Melo MB, Parroche P, Junqueira CF, Teixeira SM, Sirois C, Kasperkovitz P, Knetter CF, Lien E, Latz E, et al. Recruitment and endo-lysosomal activation of TLR9 in dendritic cells Infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:1333–1344. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AM, Bellet MM, Sassone-Corsi P, O'Neill LA. Circadian clock proteins and immunity. Immunity. 2014;40:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danquah I, Bedu-Addo G, Mockenhaupt FP. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and increased risk for malaria infection. Emerging infectious diseases. 2010;16:1601–1604. doi: 10.3201/eid1610.100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David PH, Hommel M, Benichou JC, Eisen HA, da Silva LH. Isolation of malaria merozoites: release of Plasmodium chabaudi merozoites from schizonts bound to immobilized concanavalin A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1978;75:5081–5084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel-Mahan K, Sassone-Corsi P. Metabolism and the circadian clock converge. Physiological reviews. 2013;93:107–135. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel-Mahan KL, Patel VR, de Mateo S, Orozco-Solis R, Ceglia NJ, Sahar S, Dilag-Penilla SA, Dyar KA, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P. Reprogramming of the circadian clock by nutritional challenge. Cell. 2013;155:1464–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elased K, Playfair JH. Hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in rodent models of severe malaria infection. Infection and immunity. 1994;62:5157–5160. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5157-5160.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanueli C, Graiani G, Salis MB, Gadau S, Desortes E, Madeddu P. Prophylactic gene therapy with human tissue kallikrein ameliorates limb ischemia recovery in type 1 diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2004;53:1096–1103. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J, Bar-Joseph Z. STEM: a tool for the analysis of short time series gene expression data. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falanga PB, D'Império Lima MR, Coutinho A, Pereira da Silva L. Isotypic pattern of the polyclonal B cell response during primary infection by Plasmodium chabaudi in normal and immune-protected mice. European journal of immunology. 1987;17:599–603. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin BS, Parroche P, Ataide MA, Lauw F, Ropert C, de Oliveira RB, Pereira D, Tada MS, Nogueira P, da Silva LH, et al. Malaria primes the innate immune response due to interferon-gamma induced enhancement of toll-like receptor expression and function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:5789–5794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809742106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautret P, Deharo E, Chabaud AG, Ginsburg H, Landau I. Plasmodium vinckei vinckei, P. v. lentum and P. yoelii yoelii: chronobiology of the asexual cycle in the blood. Parasite. 1994;1:235–239. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1994013235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzinelli RT, Kalantari P, Fitzgerald KA, Golenbock DT. Innate sensing of malaria parasites. Nature reviews Immunology. 2014;14:744–757. doi: 10.1038/nri3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon EB, Hart GT, Tran TM, Waisberg M, Akkaya M, Skinner J, Zinocker S, Pena M, Yazew T, Qi CF, et al. Inhibiting the Mammalian target of rapamycin blocks the development of experimental cerebral malaria. mBio. 2015;6:e00725. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00725-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawking F. The clock of the malaria parasite. Scientific American. 1970;222:123–131. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0670-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirako IC, Ataide MA, Faustino L, Assis PA, Sorensen EW, Ueta H, Araujo NM, Menezes GB, Luster AD, Gazzinelli RT. Splenic differentiation and emergence of CCR5+CXCL9+CXCL10+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells in the brain during cerebral malaria. Nature communications. 2016;7:13277. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosack DA, Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome biology. 2003;4:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta CT, Gazarini ML, Beraldo FH, Varotti FP, Lopes C, Markus RP, Pozzan T, Garcia CR. Calcium-dependent modulation by melatonin of the circadian rhythm in malarial parasites. Nature cell biology. 2000;2:466–468. doi: 10.1038/35017112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Kim J, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2012;52:381–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari P, Deoliveira RB, Chan J, Corbett Y, Rathinam V, Stutz A, Latz E, Gazzinelli RT, Golenbock DT, Fitzgerald KA. Dual Engagement of the NLRP3 and AIM2 Inflammasomes by Plasmodium-Derived Hemozoin and DNA during Malaria. Cell reports. 2014;6:196–210. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D. Febrile temperatures can synchronize the growth of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1989;169:357–361. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D, Nowak M. Periodic and chaotic host-parasite interactions in human malaria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:5111–5113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. The Journal of parasitology. 1979;65:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Sanni LA, Omer F, Riley E, Langhorne J. Pathology of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection and mortality in interleukin-10-deficient mice are ameliorated by anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha and exacerbated by anti-transforming growth factor beta antibodies. Infection and immunity. 2003;71:4850–4856. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4850-4856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima WR, Tessarin-Almeida G, Rozanski A, Parreira KS, Moraes MS, Martins DC, Hashimoto RF, Galante PA, Garcia CR. Signaling transcript profile of the asexual intraerythrocytic development cycle of Plasmodium falciparum induced by melatonin and cAMP. Genes & cancer. 2016;7:323–339. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J, Lucas R, Grau GE. Pathogenesis of cerebral malaria: recent experimental data and possible applications for humans. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2001;14:810–820. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.810-820.2001. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancio-Silva L, Slavic K, Grilo Ruivo MT, Grosso AR, Modrzynska KK, Vera IM, Sales-Dias J, Gomes AR, MacPherson CR, Crozet P, et al. Nutrient sensing modulates malaria parasite virulence. Nature. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nature23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]