Abstract

Background

Men with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may have increased sexual dysfunction. To measure the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in our male patients, we aimed to develop a new IBD-specific Male Sexual Dysfunction Scale (the IBD-MSDS).

Methods

We used a cross-sectional survey and enrolled male patients (N = 175) ≥18 years old who attended IBD clinics at 2 Boston hospitals. We collected information on sexual functioning via a 15-item scale. General male sexual functioning was measured using the International Index of Erectile Dysfunction (IIEF); the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) measured depressive symptoms. Medical history and sociodemographic information were extracted from medical record review. Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) assessed unidimensionality, factor structure, reliability, and criterion and construct validity of the 15-item scale. We used regression models to identify clinical factors associated with sexual dysfunction.

Results

EFA suggested retaining 10-items generating a unidimensional scale with strong internal consistency reliability, α = 0.90. Criterion validity assessed using Spearman’s coefficient showing that the IBD-MSDS was significantly correlated with all the subscales of the IIEF. The IBD-MSDS was significantly correlated (construct validity) with the PHQ-9 (P < 0.001) and the composite score for active IBD cases (P < 0.05). Male sexual dysfunction in IBD was significantly associated with the presence of an ileoanal pouch anastomosis (P = 0.047), depression (P < 0.001), and increased disease activity (P = 0.021).

Conclusions

We have developed and validated an IBD-specific scale to assess the psychosexual impact of IBD. This new survey tool may help physicians screen for and identify factors contributing to impaired sexual functioning in their male patients.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, sexual dysfunction, ulcerative colitis, men

INTRODUCTION

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory intestinal disorders resulting in significant morbidity and impaired quality of life. Psychosexual function in IBD is particularly relevant given that the peak incidence and prevalence is between the ages of 15–35 years. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) often require invasive abdominal and pelvic surgery and the use of potent immune modulating and biological therapies. IBD symptoms, disease complications, and treatments influence body image, intimacy, and sexual function.1 Despite the clear significance of these issues, knowledge of the extent and impact of sexual dysfunction in men with IBD is scarce. Most data have been derived from case reports, small survey-based studies that are not validated in IBD patients, and few meta-analyses.2

To our knowledge, there are no IBD-specific validated questionnaires addressing sexuality issues. Recent studies and surveys have used generic validated questionnaires such as the International Index of Erectile Dysfunction (IIEF), the gold standard for measuring general male sexual function,3 and applied them to the field of IBD.4–7 The IIEF assesses erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction. However, it is a generic instrument and therefore lacks IBD- specific domains. Historically, the development of the IIEF paralleled the advent of sildenafil and much of the evidence is derived from older patient populations, classically those with diabetes and vascular disease.8 There are IBD-specific validated questionnaires that have been used to measure quality of life and disease activity but these look at sexual function only peripherally. For instance, the short and long forms of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire (IBDQ) measure quality of life in IBD and the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Clinical Activity Index, and Colitis Activity Index measure disease activity.9–11 In addition, patients with active IBD more often report severe depression than patients in remission,12,13 and the generic Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale has been used to explore anxiety and depression in IBD patients.14 However, this questionnaire does not address specific IBD-related concerns.

IBD affects men during the peak years of dating, marriage, conception, and child-rearing. Many patients have questions regarding the effect of medical therapy, surgical therapy, and disease activity on sexual function. Therefore, a new tool is needed to assess specific domains measuring the psychosexual impact of IBD in men, including domains measuring psychosexual concerns of patients who have had surgery, perianal fistulae, and symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fatigue, all of which are commonly seen in IBD.

In this study, we conducted a psychometric evaluation of a new IBD-specific scale that measures sexual functioning in a population of male patients with IBD (the IBD-Male Sexual Dysfunction Scale or IBD-MSDS). Our goal was to determine the psychometric properties of the IBD-MSDS, the criterion validity of the IBD-MSDS in relation to the IIEF, and the construct validity of the IBD-MSDS in relation to variables in the dataset that measured depression and IBD activity. Using this new scale, we aimed to assess of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in our patient population and to identify associated factors that may be preventable, reversible, and treatable.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Item Selection and Content Validity

Our research team followed a three-step process to ensure that a specific set of items measured the content domain, which should be a subset of the universe of appropriate items.15 First, a literature search of existing questionnaires was conducted to identify relevant domains of sexual functioning in IBD, and a preliminary set of items was created in consultation with an expert in the field of survey development and an endocrinologist specializing in men’s health. Second, we reviewed the initial battery of survey items with an expert panel and then piloted these items with a focus group consisting of 10 male IBD patients to refine the wording and content that reflected the underlying construct, IBD-specific male sexual dysfunction. Wording of items was reviewed for appropriateness of content, language level, type and form, sequence, and how information would be sought from the respondents.

Third, based on the outcomes of the first and second steps, an IBD-specific MSDS was developed inclusive of 15-items (Table 1). Each individual item was scored from 0 to 4 points on a Likert-type scale, with the highest score indicating greater severity of sexual dysfunction to facilitate interpretability for use by clinicians (4 = Always or almost always; 3 = Most times (more than half the time); 2 = About half the time; 1 = A few times (less than half the time); and 0 = Never or very rarely). The 15-items measured how CD or UC affected sexual functioning related to: desire, preventing one from having sex, causing problems during sex, feeling guilty about sex, feeling fatigue or lack of energy, abdominal or pelvic pain, increased bowel movements, anal bleeding or discharge, anal pain, discomfort or irritation, joint pain, fear of participating in sexual activity, fear of passing gas, fear of passing stool, fear of experiencing abdominal or pelvic pain, and fear of appliance leaking during sexual activity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Preliminary IBD-Specific Male Sexual Dysfunction Scale (15 Items)

| 1. In the last year how frequently has CD or UC affected your desire for sexual activity? |

| 2. In the last year has having CD or UC prevented you from having sex? |

| 3. In the last year has having CD or UC caused problems during sex? |

| 4. In the last year has having CD or UC caused you to feel guilty about intimacy or intercourse? |

| 5. In the last year to what extent has fatigue or lack of energy impacted your sex life? |

| 6. In the last year to what extent has abdominal or pelvic pain affected your sex life? |

| 7. In the last year how much has increased bowel movement frequency affected your sex life? |

| 8. In the last year how much has anal bleeding or discharge affected your satisfaction with your sex life? |

| 9. In the last year how much has anal pain, discomfort, or irritation affected your satisfaction with your sex life? |

| 10. In the last year how much has joint pain affected your satisfaction with your sex life? |

| 11. Are you ever afraid of participating in sexual activity due to your CD or UC? |

| 12. Do you fear passing gas during sexual activity? |

| 13. Do you fear passing stool during sexual activity? |

| 14. Do you fear experiencing abdominal/pelvic pain during sexual activity? |

| 15. Do you fear your appliance leaking (ostomy bag) during sexual activity? |

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity evaluated whether the new IBD-MSDS had an empirical association with the IIEF, which is considered the “gold standard” measure of sexual functioning in males. The IIEF includes a 15-item self-evaluation scale with subscales for: erectile function (score range 0–30), orgasmic function (score range 0–10), sexual desire (score range 0–10), satisfaction in sexual intercourse (score range 0–15), and general satisfaction (score range 0–10).3 The highest score on each subscale indicates no sexual dysfunction; therefore, we hypothesize that the IBD-MSDS will have an inverse correlation with the IIEF.

Construct Validity

Construct validity is concerned with the theoretical relationship of the new scale with other variables in the dataset known to have an association with IBD. Based on the literature review, we hypothesized that sexual dysfunction in male patients with IBD would be positively correlated with depression and increased IBD activity.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which is a brief self-report screening instrument that focuses on the 9 diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV depressive disorders16: anhedonia, depressed, sleep problems, low energy, appetite problems, low self-esteem, trouble concentrating, psychomotor problem, and suicide ideation. In a meta-analytical review, the PHQ-9 has been deemed acceptable for depression screening in a range of settings, countries, and populations.17–33 The PHQ-9 asks whether a symptom has been present more than half the time, over the past 2 weeks. The instrument uses a Likert-type response format ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (everyday), and the total score ranges from 0 to 27 with 5 severity categories: minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe (20–27).16 A higher score indicates greater depressive symptomatology; therefore, we hypothesized that the IBD-MSDS would have a positive correlation with the PHQ-9.

IBD Clinical Activity Indices

We used the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI)34 for patients with CD. A score of 5 or greater is generally considered to represent active clinical disease; therefore, we hypothesized that the IBD-MSDS would have a positive correlation with the HBI. We used the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI)11 in patients with UC. A score of 5 or greater is generally considered to represent active clinical disease; therefore, we hypothesized that the IBD-MSDS would have a positive correlation with the HBI and SCCAI. We defined an HBI or SCCAI of 5 or greater as an Active IBD Score.

Study Design, Recruitment and Study Sites

This study used homogenous purposive sampling in a cross-sectional design. Male patients with IBD were recruited and enrolled while attending the adult gastroenterology clinics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, between November 1, 2013 and April 30, 2015.

Participants: Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Male patients, 18 years of age or older, were invited to complete the survey at or before attendance at the IBD clinic. Most patients filled in the survey during their clinic appointment. If a patient had time constraints, he was given an envelope to mail back the response. Some patients (10%) were sent the survey in the mail before an upcoming clinic appointment. We excluded 1 patient from the study who had impotence following prostatectomy for prostate cancer. The response rate was 40% (225/560), and of 225 surveys returned, 175 were fully completed.

Data Collection

A structured paper questionnaire was administered to study participants capturing information on sexual behaviors and the perceived impact of IBD symptoms, medications, and surgery on sexual function. The IIEF and PHQ-9 were administered simultaneously. A medical record review was performed for each patient, with information extracted including demographics, disease type, medications, surgery, perianal disease, and medical comorbidities. All clinical disease activity index scores were obtained directly from the patient, in person, by the physician at the time of the clinic appointment.

Participant Compensation

The patients were not compensated for participation in the study.

Statistical Analyses

Exploratory factor analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was appropriate for this study because the 15 items had not been previously evaluated as a hypothetical scale that measured the underlying construct “Sexual Dysfunction in IBD.” EFA assisted in determining whether the underlying construct was unidimensional, and the Stata default principal factor method was used, which allowed each item to have its own variance, in which each observed item (χ1-χ15) had a corresponding unique random error term, ε1-ε15, reflecting there was no shared variance between the 15 items.35–37 Goodness of fit was assessed using the Satorra-Bentler Chi-Squared Statistics for the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI).38 Stata v1439 and Microsoft Excel40 were used to analyze the data.

Descriptive statistics

Univariate statistics were generated and ceiling/floor effects were considered substantial if ≥20% of subjects scored at the upper-most or bottom-most end on the IBD-MSDS.41,42 Internal consistency reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha statistic.15 Criterion and construct validity were assessed using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, with significance P < 0.05.

We used REDCAP and the STATA program for multivariate regression modeling.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical approval was granted by the Partners Health Care Institutional Review Board in October 2014, Protocol Number: 2013P002222.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

A total of 225 participated in the study. After data entry, 50 questionnaires were removed from analysis either because of very incomplete data or noneligibility. Of the remaining 175 participants, the mean age was 43.2 years (SD ± 13.8, range 20–84); 62.9% were married and the majority of study participants reported white race (92.0%; N = 160/174) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Male | 175 (100) |

| Age (years) (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | 43 ± 13.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 92 |

| Black | 2.9 |

| Hispanic | 2.3 |

| Asian | 2.9 |

| Marital Status (%) | |

| Married/Long-term partner | 62.9 |

| Single | 34.9 |

| Divorced | 2.2 |

| IBD (%) | |

| CD | 57 |

| UC | 43 |

| Duration of disease (years) (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | 14 ± 11.7 |

| Disease Activity | |

| Harvey-Bradshaw Index (% Score ≥5; N = 15/94) | 16 |

| SCCAI (% Score ≥5; N = 6/73) | 8.2 |

| Surgical Status (%) | |

| IPAA | 7.8 |

| Ostomy | 9.3 |

| Perianal disease (%) | 15.6 |

| Current medications (%) | |

| Corticosteroids | 7.4 |

| Anti-TNF alpha | 42.2 |

| Anti IL12/23 | 3.4 |

| Immunomoldulators | 26.7 |

| Narcotics | 2.3 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |

| Endocrine | 10.9 |

| Cardiovascular | 17.7 |

| Smoking Status (%) | |

| Current | 4.6 |

| Ex-smoker | 23 |

| Non-smoker | 73.4 |

| IBD-MSDS Scores (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | 4.6 ± 6.2 |

| IIEF Scores (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | |

| Erectile Function | 22.9 ± 9.6 |

| Orgasmic Function | 8.3 ± 2.8 |

| Sexual Desire | 7.6 ± 2.2 |

| Satisfaction in Sexual Intercourse | 9.9 ± 4.8 |

| General Satisfaction | 7.1 ± 2.4 |

| PHQ-9 Score (%) | |

| Minimal | 59.8% |

| Mild | 21.3% |

| Moderate | 10.9% |

| Moderately Severe | 5.2% |

| Severe | 2.9% |

Survey Results

In the past year, 156 patients had sex with women, 9 with men, and 10 did not have sex at all. Eighty-six percent were in a current relationship. Twenty-one percent reported hesitancy starting a new relationship due to IBD and in 14% IBD contributed to a break-up. IBD had a negative effect on libido for 38%, prevented sex in 27%, and caused problems during sex for 18%. Twenty percent of patients reported feeling guilty about sex and 30% feared sex. Symptoms affecting sexual activity included fatigue (35%), abdominal pain (23%), rectal bleeding (20%), and increased bowel movements (25%). Body image was impaired by ileoanal pouch anastomosis surgery (IPAA) (3%), setons (2%), ostomy (9%), perianal fistulae (10%), and scars (12%). Twenty-three percent of patients were using erectile enhancing medications, and 5% were using testosterone to improve sexual function.

Seventy-eight percent of patients reported that they would feel comfortable talking to their doctor about sex, although only 10% reported their IBD provider initiating a conversation about sex. Seventy-two percent had no preference for a male or female provider, and 22% would feel more comfortable talking to a male provider.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

An examination of the 15-item scale showed a factor structure with potentially 2 underlying constructs being measured. Factors 1 and 2 had eigenvalues equal to 6.73 and 1.11, respectively. Examining the factor loadings for Factor 2, 3 of the fear items (Items 12, 13, and 14) had positive loadings ≥0.30 on both Factors 1 and 2, which was the minimum criteria for an item (Table 3). We performed a promax rotation assuming that Factors 1 and 2 were correlated because “fear of passing gas, stool or experiencing abdominal/pelvic pain during sexual activity” was likely to influence sexual functioning. The rotated factor structure showed that all the fear items (Items 12, 13, 14, and 15) had positive loadings ≥0.30 on Factors 2 only, as well as Item 10, which asks “how much joint pain affected your satisfaction with your sex life” (Supplementary Table 1). Dropping these 5 items, a rerun of EFA returned a 1-Factor Model, with Factor 1 and 2 having an eigenvalue equal to 5.34 and 0.64, respectively. Factor loadings for the 1-Factor model ranged from 0.58 to 0.82. Our final IBD-MSDS is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Final IBD-Specific Male Sexual Dysfunction Scale (10 Items)

| 1. In the last year how frequently has CD or UC affected your desire for sexual activity? |

| 2. In the last year has having CD or UC prevented you from having sex? |

| 3. In the last year has having CD or UC caused problems during sex? |

| 4. In the last year has having CD or UC caused you to feel guilty about intimacy or intercourse? |

| 5. In the last year to what extent has fatigue or lack of energy impacted your sex life? |

| 6. In the last year to what extent has abdominal or pelvic pain affected your sex life? |

| 7. In the last year how much has increased bowel movement frequency affected your sex life? |

| 8. In the last year how much has anal bleeding or discharge affected your satisfaction with your sex life? |

| 9. In the last year how much has anal pain, discomfort, or irritation affected your satisfaction with your sex life? |

| 10. Are you ever afraid of participating in sexual activity due to your CD or UC? |

Assessing Goodness of Fit

It was assumed that the observed variables were not normally distributed, therefore, the Satorra–Bentler Scaled Chi-Squared test was used because it is robust to nonnormality. Results show that the RMSEA_SB (generated by the Satorra-Bentler command in Stata) was 0.103 on the remaining 10 items, which was higher than the recommended range of 0.05 for a good fit, and less than 0.08 for a reasonably good fit.38 The Comparative Fit Index (CFI _SB) was 0.855, which means that our model does 85.5% better than a null model in which we assume the items are all unrelated to each other; whereas, the recommended cutoff should be either 0.90 or 0.95.38

Output of Modification Indexes

The output of modification indexes was generated showing error terms for items that should be correlated. The largest modification index (MI) found was between Items 8 and 9, with an MI equal to 66.025, suggesting they were more correlated with each other than with the other 10 items. Both items focus on anal discomfort during sexual activity. By correlating these items, the RMSEA_SB reduced to 0.064 and the CFI-SB increased to 0.946.

Descriptive Statistics and Reliability of the IBD-MSDS

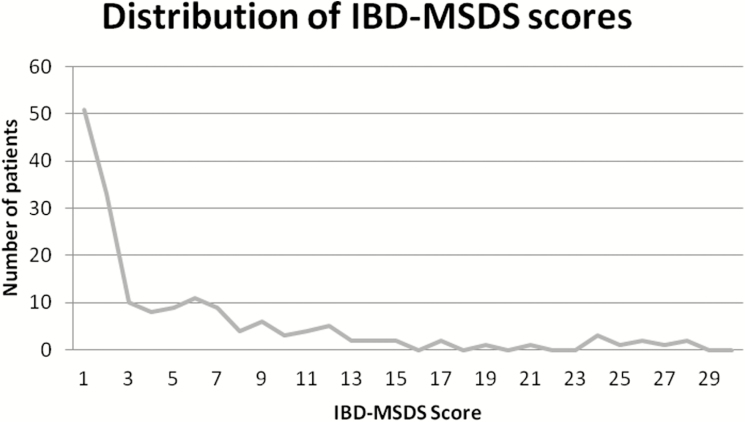

Univariate statistics show a mean IBD-MSDS of (x¯ = 4.6 ± 6.2) with a range of 0–27 points, with a higher score indicating greater sexual dysfunction. There were floor effects observed, with 29.1% (N = 51/175) of study participants having a minimum score of 0, suggesting no experiences of sexual dysfunction, yet no ceiling effects were observed in this study population. The Cronbach coefficient alpha is α = 0.90, confirming that a large proportion of the scale’s total variance is attributed to a common source. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the IBD-MSDS scores.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of IBD-MSDS Scores.

A stratified analysis across educational level and age groups was performed. Reliability across educational level was consistent at α = 0.90 for individuals with high school, some postsecondary education, and participants who graduated with a postsecondary education. Reliability across ages groups (18–29, 30–45, 46–59, and 60–86) showed that participants in the youngest age group have a lower scale reliability (18–29: α = 0.83, 30–45: α = 0.92, 46–59: α = 0.88, 60–86: α = 0.92) compared with the older participants, which might suggest greater discomfort (or uneasiness) to respond to questions about sexual dysfunction in IBD.

Criterion and Construct Validity

Using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, the 10-item IBD-MSDS was highly significant, and inversely correlated with all the subscales of the IIEF: erectile function (N = 173; r = -0.2730, P < 0.05), orgasmic function (N = 173; r = -0.2594, P < 0.05), sexual desire (N = 173; r = -0.3074, P < 0.001), satisfaction in sexual intercourse (N = 172; r = -0.1819, P < 0.05), and general satisfaction (N = 172; r = -0.2654, P < 0.05). Supplementary Figure 1 shows these distributions, which establishes strong criterion validity. Similarly, the IBD-MSDS was highly significant and positively correlated with the summary score for the PHQ-9 (N = 174; r = 0.4431, P < 0.001) and with the Active IBD Score (N = 167; r = 0.2883, P < 0.05). Supplementary Figure 2 shows these distributions, which establishes strong construct validity.

Regression Analysis

Male sexual dysfunction as measured by the IBD-MSDS is significantly associated with the presence of an IPAA (P = 0.047), mild, moderate, or severe depression (P < 0.001), active IBD (P = 0.021), previous history of smoking (P = 0.021); and marginally associated with the presence of an ostomy (P = 0.103), endocrine-related comorbidities (0.098), and cardiac-related comorbidities (P = 0.063) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Regression Analysis of Factors Contributing to Sexual Dysfunction as Measured by the IBD-MSDS

| Variable | Beta Coefficient | Standard error | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostomy | 3.4 | 2.1 | 0.103 |

| IPAA | 3.8 | 1.9 | 0.047 |

| PHQ > 5 | 52 | 0.09 | 0.000 |

| IBD Activity (HBI/SCCAI ≥ 5) | 3.4 | 1.5 | 0.021 |

| Previous smoker | -3.2 | 1.3 | 0.021 |

| Endocrine-related comorbidities | 3.0 | 1.8 | 0.098 |

| Cardiac-related comorbidities | 2.5 | 1.4 | 0.063 |

DISCUSSION

The IBD-MSDS is a novel tool to assess sexual functioning in male patients with IBD. Impairments in psychosexual functioning remain underdiagnosed, which reflects the lack of an IBD-specific screening tool, poor physician awareness, and a reluctance to discuss issues of an intimate nature with one’s IBD provider. A striking finding reproduced in numerous studies is that disease activity relates strongly to impaired psychological function, and the most consistently reported risk factor for sexual problems in IBD patients are coexisting mood disorders.43,44 Disease activity appears to have a significant impact on libido, sexual attractiveness, level of sexual activity, and enjoyment of sex.5

We found that male sexual dysfunction in IBD is significantly associated with the presence of an IPAA, mild, moderate or severe depression, and active IBD. We hypothesized that the presence of an ostomy would impair sexual function; this was marginally but not statistically significant. Only 15 patients had an ostomy, therefore, we may not have had sufficient cases to show a significant association. Similarly, steroid and narcotic use have been shown to decrease testosterone levels. Twelve of our patients were using steroids and 4 were using narcotics and these small numbers may not have been sufficient to demonstrate significant associations.

Psychometric evaluation of the final 10-item instrument was assessed in 3 major ways: (1) reliability, (2) criterion validity, and (3) construct validity. Overall, the 10-item IBD-MSDS has strong internal consistency reliability. Using Spearmen’s correlation coefficient, strong criterion validity was noted with all the subscales of the IIEF; and positive statistically significant associations (construct validity) were shown with the measure for depression and the composite score for active IBD cases.

A limitation to this study is that both for initial validation and subsequent screening, a cross-sectional observational cohort was utilized. Since the validation is in a single city setting, bias may be increased along with limitations of generalizability. However, we hope to counter this by ensuring that a wide spectrum of patients was offered participation in the study. Possible recall bias may be present; to limit this, medical records were reviewed to verify clinical information and a longitudinal assessment of each patient’s medical history. In addition, an evaluation of clinical disease activity (either the HBI or the SCCAI) was ascertained by the physician from the patient at the time of the clinic appointment. Methodologically, test-retest repeatability in a longitudinal design is more desirable to assess scale reliability, along with the evaluation of responsiveness when study participants are enrolled in a pre/post treatment design. Unfortunately, we do not have endoscopic data here, but we suggest that future studies might include endoscopic and biochemical endpoints.

Furthermore, this new tool warrants further evaluation and should be used as an adjunct to, rather than a substitute for, a detailed history of sexual dysfunction in men with IBD.

In conclusion, we have developed and validated a novel tool to assess the specific psychosexual impact of IBD. We hope that it can be used for clinical and research purposes to diagnose sexual dysfunction in male patients with IBD. We propose that IBD physicians assume a proactive role in screening for and identifying factors contributing to impaired sexual function in our IBD patients. Specifically, we should strive for disease remission and screen for underlying depression in our patients.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Inflammatory Bowel Diseases online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts to report.

Supported by: Analyses of data and manuscript development was financially supported, in part, by a grant awarded to MAT from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI Program Award CE-1304-6756), and by a grant (L60 MD002421-02) and fellowship (R25MH083620) awarded to LGM from the National Institutes of Health.

Prior Presentations: Digestive Disease Week, Washington DC, 2015.

Guarantor of the Article: Aoibhlinn O’Toole, MD.

Specific Author Contributions: Study investigators took part in conducting, interpreting, and drafting the manuscript: Aoibhlinn O’Toole, Disentuwahandi Punyanganie De Silva, Amanda Ting, Alan Moss, and Josh Korzenik. Marcia A. Testa, Linda G. Marc, and Christine A. Ulysse were responsible for analysis and drafting the manuscript. Sonia Friedman approved the final draft of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giese LA, Terrell L. Sexual health issues in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1996;19:12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantzouranis G, Fafliora E, Glanztounis G, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and sexual function in male and female patients: an update on evidence in the past ten years. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:1160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmer A, Bauer A, Dignass A, Rogler G. Sexual function in persons with inflammatory bowel disease: a survey with matched controls. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timmer A, Bauer A, Kemptner D, et al. Determinants of male sexual function in inflammatory bowel disease: a survey-based cross-sectional analysis in 280 men. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moody GA, Mayberry JF. Perceived sexual dysfunction amongst patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 1993;54:256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Gendrano N 3rd. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a state-of-the-science review. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:226–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National cooperative Crohn’s disease study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandler RS, Jordan MC, Kupper LL. Development of a Crohn’s index for survey research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graff LA, Walker JR, Lix L, et al. The relationship of inflammatory bowel disease type and activity to psychological functioning and quality of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bokemeyer B, Hardt J, Hüppe D, et al. Clinical status, psychosocial impairments, medical treatment and health care costs for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Germany: an online IBD registry. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:355–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iglesias-Rey M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Caamaño-Isorna F, et al. Psychological factors are associated with changes in the health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeVellis RF.Scale development: theory and applications. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyne JC, Thombs BD, Mitchell AJ. PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 in western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:890; author reply 891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the patient health questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbody S, Sheldon T, House A. Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2008;178:997–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbody S, Sheldon T, Wessely S. Should we screen for depression?BMJ. 2006;332:1027–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, et al. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams JW Jr, Pignone M, Ramirez G, Perez Stellato C. Identifying depression in primary care: a literature synthesis of case-finding instruments. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:225–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marc LG, Henderson WR, Desrosiers A, et al. Reliability and validity of the Haitian Creole PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, et al. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, et al. Using the patient health questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:547–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker S, Al Zaid K, Al Faris E. Screening for somatization and depression in Saudi Arabia: a validation study of the PHQ in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32:271–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wulsin L, Somoza E, Heck J. The feasibility of using the spanish PHQ-9 to screen for depression in primary care in Honduras. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4:191–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omoro SA, Fann JR, Weymuller EA, et al. Swahili translation and validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 depression scale in the Kenyan head and neck cancer patient population. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:367–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Afolabi OO. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. J Affect Disord. 2006;96:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okulate GT, Olayinka MO, Jones OB. Somatic symptoms in depression: evaluation of their diagnostic weight in an African setting. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:422–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Willig JH, et al. Measuring depression levels in HIV-infected patients as part of routine clinical care using the nine-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9). AIDS Care. 2010;22:874–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Atkinson JH, et al. ; Veterans Aging Cohort 5-Site Study Project Team. Psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders among HIV-positive and negative veterans in care: veterans aging cohort five-site study. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nunnally JC.Psychometric Theory. 2nd ed New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coste J, Bouée S, Ecosse E, et al. Methodological issues in determining the dimensionality of composite health measures using principal component analysis: case illustration and suggestions for practice. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:641–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raykov T, Marcoulides GA.. A First Course in Structural Equation Modelling. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.StataCorp LP. Stata user’s guide. Release 12. College Station, Tex: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel [computer program]. Redmond, Washington: Microsoft Corp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Testa MA, Nackley JF. Methods for quality-of-life studies. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:535–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marc LG, Wang MM, Testa MA. Psychometric evaluation of the HIV symptom distress scale. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1432–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ananthakrishnan AN, Gainer VS, Cai T, et al. Similar risk of depression and anxiety following surgery or hospitalization for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho HS, Park JM, Lim CH, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver. 2011;5:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.