Abstract

American Indians (AIs) have experienced traumatizing events but practice remarkable resilience to large-scale and long-term adversities. Qualitative, community-based participatory research served to collect urban AI elders’ life narratives on historical trauma and resilience strategies. A consensus group of 15 elders helped finalize open-ended questions that guided 13 elders in telling their stories. Elders shared multifaceted personal stories that revealed the interconnectedness between historical trauma and resilience, and between traditional perceptions connecting past and present, and individuals, families, and communities. Based on the elders’ narratives, and supported by the literature, an explanatory Stories of Resilience Model was developed.

INTRODUCTION

In 2010, American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) living in urban areas made up 78% of the total number of AI/ANs in the U.S. (Norris, Vines, & Hoeffel, 2012, p. 12); many were descendants of those who first came to urban areas during the federal government relocation policy that started in the 1950s (National Urban Indian Family Coalition [NUIFC], 2011). NUIFC (2011) defines the urban Indian population as “individuals of American Indian and Alaska Native ancestry who may or may not have direct and/or active ties with a particular tribe, but who identify with and are at least somewhat active in the Native community in their urban area.” In 2010, the urban AI/AN population in Tucson, Arizona was 14,055––2.7% of a total population of 520,570 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). An estimated 20.3% of this Tucson urban AI population was age 45 years and older (Urban Indian Health Institute [UIHI], 2011).

AI/ANs in urban areas experience higher rates of poverty, unemployment, low education, homelessness and health disparities compared to the general population (NUIFC, 2011). In Tucson, 35.2% AI/ANs live below the federal poverty rate in comparison to 15.7% of the general population. AI/ANs over the age of 16 years experience higher rates of unemployment (20.9%) than the general population (7.4%). Heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury, diabetes, and chronic liver disease are the top five causes of mortality for the Tucson AI/AN population (UIHI, 2011). While urban AI/ANs share many of these socioeconomic and health disparities with AI/ANs living on tribal lands, urban residents face unique challenges, including separation from tribal support networks (NUIFC, 2011).

Despite differences, the families and ancestors of both urban and reservation-based AI/ANs have experienced similar sociohistorical stressors that contribute to historical trauma. Few studies to date have focused on the resilience of urban AIs (Myhra, 2011) or AI elders (Grandbois & Sanders, 2009). This study gathered urban AI elders’ life narratives to document resilience strategies for coping with life stressors in the context of historical trauma. The stories collected offered a window into perceptions of and experiences with stress and resilience.

Historical Trauma

The contemporary social, economic, and health disparities of AIs are linked to historically traumatic events of colonization, national policies, and government practices aimed at assimilating AI tribes into mainstream America (Brave Heart, 2003; Brave Heart, Chase, Elkins, & Altschul, 2011; Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Goodkind, Hess, Gorman, & Parker, 2012; Washburn, 1988). These historical processes resulted in reduced population numbers, more sedentary lifestyles, disrupted social structures, and culture loss (Brave Heart et al., 2011; Washburn, 1988). Brave Heart (2003, p. 7) defined historical trauma as “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding, over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma.” Historical trauma resulted in historical trauma response, including a cluster of symptoms or maladaptive behaviors associated with unresolved historical grief. Transmitted across generations (Brave Heart et al., 2011), this unresolved intergenerational distress has been conceptualized as one underlying factor for current higher rates of ill health, and the loss of traditional values and practices as a contributing factor in unhealthy lifestyle changes (Berg et al., 2012; Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Stumblingbear-Riddle & Romans, 2012).

Resilience

During the first 50 years of resilience research in psychology and psychiatry, researchers (e.g., Anthony, 1987; Rutter, 1985) focused on individual resilience mostly by examining the positive development of children and youth in adversity from non-Indigenous perspectives and with little attention to the social context (i.e., family, community, culture). These early concepts of individual resilience as a personal trait were replaced by an understanding of individual resilience as a process largely driven by social, cultural, and physical contexts (Fleming & Ledogar, 2008; Kirmayer, Dandeneau, Marshall, Phillips, & Williamson, 2011; Kirmayer, Sehdev, Whitley, Dandeneau, & Isaac, 2009; Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Ungar, 2008, 2011; Wexler, 2013). More recently, Ungar (2008, 2011) has argued that the construct of resilience has experienced a shift in focus to contextual factors and become viewed as multidimensional and flexible:

In the context of exposure to significant adversity, whether psychological, environmentally, or both, resilience is both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to health-sustaining resources, including opportunities to experience feelings of well-being, and a condition of the individual’s family, community and culture to provide these health resources and experiences in culturally meaningful ways (Ungar, 2008, p. 225).

A social ecological definition (Ungar, 2012a, 2012b, 2011) draws attention to resilience at levels larger than the individual. Within the socioecological model, family interacts with the larger community and its social systems, drawing on culture and identity to promote resilience. Community systems themselves can demonstrate resilience by achieving balance within changing contexts. Community resilience entails relational and collective processes where individuals, family units, communities, and the larger environment are interconnected, yielding protective factors to counter adversities (Kirmayer et al., 2009).

Kirmayer and colleagues (2011, 2012) suggest that community resilience is compatible with Indigenous values of relationships among people and with the environment. Distinct notions of personhood, where individuals are connected to the land and the environment, shape Indigenous ideas of individual resilience. Indigenous views of community resilience include revisioned collective histories that value Indigenous identity; the revitalization of language, culture, and spirituality; traditional activities; collective agency; and activism. Oral history and storytelling are traditional means of conveying cultural notions of personhood, value systems, and strategies of resilience (Denham, 2008; Fleming & Ledogar; 2008; Goodkind et al., & Parker, 2012; Kirmayer et al., 2009, 2011, 2012). In urban settings, it may be more difficult to find shared cultural practices, as Indigenous residents may adopt multicultural values, attitudes, and activities (Kirmayer et al., 2009). For urban AI/ANs, pan-Indian activities such as powwows or sweats may function as shared cultural AI practices.

METHODOLOGY

A qualitative methods study that engaged the University of Arizona (UA) and Tucson Indian Center (TIC) used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach (Israel et al., 2003) to explore urban AI elders’ resilience strategies to cope with life stressors in the context of historical trauma.

The TIC has served a culturally diverse AI urban community for over 50 years (http://ticenter.org/). Services provided include social services, health and wellness services, and events such as health fairs and cultural celebrations. The mission of the TIC is “to lead, serve, empower and advocate for the Tucson urban American Indian Community and others, by providing culturally appropriate wellness and social services” (http://ticenter.org/). Open to the public, the TIC serves approximately 6,000 to 8,000 clients per year regardless of tribal affiliation (J. Bernal, personal communication, March 17, 2011).

University researchers worked with TIC leadership to develop a 13-person community advisory board (CAB) consisting of TIC staff, AI elders, and university researchers. We co-designed the project based on the TIC leadership’s interest in addressing elders’ concerns that loss of culture would result in poor health for Native youth (TIC, 2008), and to support the positive attitudes of elders that they held despite numerous past and current hardships (J. Bernal, personal communication, February 3, 2011). Elders were involved in the research process both in an advisory function as CAB members and/or as research participants. All research activities and protocols were approved by the UA Institutional Review Board and the TIC Board of Directors.

Procedures

Two university-based AI researchers who had prior experience working with TIC elders recruited the potential participants by verbally explaining the project activities, time commitment, and goal at the TIC. Individuals were eligible if they self-identified as AI, were 55 years of age and older, lived in Tucson, received services from the TIC, and were willing to share their stories.

Two data collection methods were used. The two university-based AI researchers who had recruited participants conducted a consensus group with 15 AI elders to discuss and finalize interview questions; the group considered draft questions developed using existing literature (Duran, 2006; Goodkind et al., 2012; Kahn-John, 2010). The discussion was audio recorded and led to the revision of the questions. AI elder feedback led to the expansion of the interview guide from the initially proposed 11 questions to 25 final questions.

This interview guide was used in a series of two face-to-face interviews with each participant to document and review each elder’s life narrative, with a focus on historical trauma and resilience strategies. Six of the 13 elders interviewed had participated in the consensus group. The first interview took 1–2 hours for each participant. Eleven elders gave approval to be video- and audiotaped, and two elders agreed to be only audiotaped. Each elder received an edited copy of their full interview. During the second interview, each elder approved or requested revisions, after which four UA research team members transcribed the interviews verbatim in preparation for qualitative analysis. One of the two audio recordings was deleted after its transcription was completed because the elder wanted to remain completely anonymous.

The interview began with the interviewer providing a culturally appropriate introduction (e.g., by sharing her tribal and clan membership, where she grew up, and current residence and occupation). The interview consisted of three sections: 1) demographic information, including personal background and connection to the Tucson urban community; 2) an open-ended, semi-structured interview focused on perceptions of the term historical trauma and culturally appropriate or alternative terms, knowledge of ancestors’ experiences of historical trauma, and impact of these experiences; and 3) open-ended questions focused on perceptions of the term resilience and culturally appropriate or alternative terms, examples of urban AI community resilience, positive experiences and factors contributing to personal and family strength and well-being, and advice for AI urban youth to address adversities.

Analysis

Qualitative analysis combined consensus (Teufel-Shone et al., 2014; Teufel-Shone, Siyuja, Watahomigie, & Irwin, 2006) and thematic analysis (Patton, 2002) approaches. The consensus approach served to develop deductive and inductive codes. Six team members read two to four of the interviews and created content codes. The first author, a trained qualitative researcher, drafted a coding book based on all team members’ codes, and organized codes into the two broad categories of historical trauma and resilience. Each category had several codes for themes and associated patterns. University researchers and one elder discussed and revised the coding book (See Appendix A, Table 1) based on consensus building.

The first author and the third author, a doctoral student, worked with the qualitative data analysis program NVivo to apply the codes in their independently conducted thematic analyses. Intercoder-reliability scores were determined and the two researchers met to discuss and build consensus about conflicted coded sections. Themes and patterns were summarized further and organized into a table by category. The analysts solicited feedback from the CAIR research team and the TIC CAB, and incorporated this feedback into their interpretation of the data analysis.

RESULTS

Several themes and associated patterns were revealed in the two categories of historical trauma and resilience. Historical trauma themes included Indigenous concepts, sense of loss, and contemporary adversities. Resilience themes were Indigenous concepts and individual, family and community resilience.

Historical Trauma

Indigenous Concepts

Most elders did not recognize the concept of historical trauma until it was described in terms of how other AI communities had defined it. The elders then redefined historical trauma in their own words; indeed, all elders told stories of historical trauma. Referring to the past, these stories talked about “disturbing times,” and “events that ancestors went through.” Elders talked about ancestors surviving specific traumatic events, such as the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota in 1890, and shared stories about specific relatives (e.g., a grandmother who escaped the Navajo’s Long Walk to Bosque Redondo in 1864). Other stories focused on grandparents and parents who lived through hard times of scarce resources, sickness and death, discrimination, and boarding schools. One elder talked about the fear related to land being taken away during colonialism, early settlers, treaties through which ancestors were tricked into signing legal documents, and the establishment of reservations. Elders referred to historical trauma as “the sadness that comes from the non-Indians oppressing us,” “historical culture shock,” loss with a focus on language (“I don’t understand my talk, my language”), “soul loneliness,” which referred to the lack of a family support system, and “continued discrimination.” These stories of historical trauma were accompanied by stories of resilience. Elders admired their grandparents and parents who had encountered adversities but knew how to survive, had skills, did not complain, and were strong.

Referring to the present, elders challenged the youths’ lack of understanding of historical trauma (as defined by the elders) and thought that if the younger generation were taught about it, the intergenerational transmission of historical trauma could be stopped. One elder suggested changing the term to “broken families” so that youth who had experienced fear associated with alcohol abuse in families would understand historical trauma. The same elder envisioned “broken families” to become “healing families.”

Sense of Loss

Elders expressed a sense of loss related to culture, language, traditions, and family life. The effects of boarding schools on their parents and grandparents seemed to be at the center of historical events leading to this loss. Elders reflected on how boarding schools must have traumatized the children who were taken away from their homes, had their hair cut, and were punished if they spoke their language. Being at boarding school meant being removed from the tribal lands that were closely tied in with culture and traditions, including subsistence practices (farming and hunting), beliefs (traditional spirituality), and values (having respect for oneself and others). Boarding schools separated children from their families, which led to a loss of contact with relatives, especially elders, who passed on culture and traditions. Family members could no longer teach Native languages or engage children in family activities. Boarding schools had long-term consequences, including “broken families” and current disruptions of family life. Some elders had alternative accounts of being removed from their families (i.e., they were adopted and raised by White families off reservation).

In their stories, elders expressed a yearning for the past that ranged from wishing they had lived during their ancestors’ times, to wanting more knowledge of culture and language to pass on to their children, to wanting to live off the land. Some quotations from elders illustrate this yearning:

I wish I was my mom sometimes. … When I see what they [elderly people] have been through … you know, it’s amazing. They are so strong and they know so much. I wish I could turn the clock and sit there at their lap or at their knees and want to hear everything that they said and did way back then. What was taught to them, because I … ask my mom “tell me some more, so I can tell my kids.”

We don’t speak it fluently so, yeah, it is kinda sad. And I wonder why and then I hear other tribes speak their language really good and fluent … you know, their language. It needs to come back to our tribe, we need to bring it back.

I also feel that the way they lived, they were strong people and they did a lot of things. I wish we could still do things the way they’d cook food, get food, harvest food or plant food … I wish that we could just go out and get our food and prepare the food…

Contemporary Adversities

Elders described contemporary adversities as continuations of past events. They understood alcohol and drugs as rooted in history with health and social consequences. They described the introduction of alcohol as part of historical trauma and described alcohol use as a coping strategy (e.g., to deal with a spouse’s death, discrimination, or not finding a job). Consequences of substance abuse mentioned by elders included family violence, children exposed to drugs and family fights, and violence among youth, including bullying and gangs. Ill health and loss of family members due to substance abuse, chronic disease, and fatal injuries were presented as contemporary adversities. The loss of relatives led to continued family separations, and loss of cultural and traditional knowledge.

Some elders talked about the poor and harsh conditions when living off the land. While they assigned high value to a subsistence lifestyle, they pointed to environmental changes that made living off the land harder. For example, one person talked about dried-up wells due to competition for water with an adjacent city.

Elders described a generational gap that contributed to youth understanding contemporary social and economic conditions out of context. They disapproved of the younger generation having lost traditions and languages, having little understanding of history and historical trauma, and having lost the value of respect. Elders seemed disappointed about the younger generation’s lack of desire to experience traditional lifestyles without electricity and running water, and their loss of survival skills. Some elders did acknowledge that these changes in interests and skills were due to history not being taught, elders not wanting to talk about or relive painful experiences, and language not being taught due to boarding school experiences. The following quotations serve as illustrations:

…they don’t understand today, their parents aren’t teaching them. …they are not gonna have knowledge of historical trauma…because historical trauma wasn’t taught in school. You know we learned that by experience.

…because when you’re hurt, you don’t want to go back and relive it and talk about it, take pictures of it, explain it.

A lot of the elders raised their children not to speak the Native language because of the barriers that they’ve faced at boarding schools.

Resilience

Indigenous Concepts

Elders primarily described the concept of resilience as individuals who experience hardship, but are “strong” and “able to handle it,” can “overcome,” “bounce back,” “better themselves” and “continue on.” “Strong” was the most recurrent word in the elders’ stories. A resilient person was described as a “survivor” (i.e., as “someone who made it through”). Some of the elders gave negative definitions, talking about “not getting stuck,” “not feeling sorry for yourself,” or “not giving up.” This focus on individual responsibility was presented in the context of history, spirituality, the family, and community. Some elders advised the younger generation to “know that in the past people went through a lot,” and “learn from the past and strong ancestors, and just be a strong person.” Resilience required “a good outlook on life,” being “grateful for what one had,” and “praying.” In the family context, some elders described resilience as “healing families.” Being “connected to the community,” “involved in local community cultural activities,” and “knowing one’s Native language” were resilience strategies in the context of the community. Another elder’s story demonstrated the connection between personal, family, and community resilience:

I think the values that I picked up when I was growing up was making my baskets. That was one of the things that REALLY was good for me, that I want to pass on to my children. …this is one of the things that I REALLY want to share. …I was taught by my mother and at first I didn’t want to sit down and make baskets (laughter). But as I grew up, I learned that it really did help me. She…showed me how to prepare to make basket: first to go out and get the plants.

She also told me that…I have to talk to the plants. You go up to the plants while you get them, so that it will help you, strengthen you, give you the courage to go on with your life and it’s really not just making baskets. It’s something that, it’s sort of like a sacred secret. So that’s what I did. I found out that that’s REALLY helped me a lot. Not just making baskets, but keeping up with our tradition, something that our people used to make and use for many things. And also, I sell my baskets a lot so that helped me in many ways. …that was my income when I couldn’t work…

Individual Resilience

Individual resilience was described as personal strength grounded in identity and spirituality. The elders talked about times they had exhibited strength (e.g., when herding sheep or riding horses as children, raising children while getting a degree, or knowing how to plant a garden or make baskets for income generation). The elders valued their ancestors’ physical, mental, and spiritual strength. Knowing “how strong the ancestors were” and having practical skills passed down from one generation to the next were part of knowing one’s identity, or “who we are.” Identity meant that individual strength was tied in with family and community strength, as well as with spirituality. An individual would gain strength by being part of a supportive family and participating in the community either one on one, in a group, or working with community organizations. One elder made the connection between personal, family, and community strength by telling her story about being adopted into a non-Indigenous family but later, as an adult, taking care of AI foster children. She strengthened her own family helping foster children turn their lives around, teaching them respect through chores and teamwork, and seeing them graduate from high school. Elders also experienced connection with and support from non-Indigenous people in urban communities (e.g., the Mexican American community), and financial and motivational support for education from non-Indigenous individuals.

Personal strength was linked to practicing spirituality regardless of religious preference, by attending church or ceremonies, praying, and asking for help. Spiritual values linking generations included “thinking about and honoring those that came before,” and “teaching young ones to pray.” One elder stressed that, while praying was an important coping strategy, individuals still had to take responsibility for themselves. She stated:

…we can ask God all we want for help... You ask: “Oh God, give me the strength, give me the power, give me the wisdom.” And he says: “You’ve already got it. I gave it to you. All you’ve got to do is use it.” And we don’t listen to that. We think it’s just going to be given to us. We have to go and look for it or use what he gave us.

The Indigenous notion of personhood connected individuals to larger contexts, including family, community, spirituality and history. As described by the elders in our study, and in the literature (Kirmayer et al., 2009, 2012), the Indigenous notion of the self/person/individual is one of connectedness. Individual resilience thus must be understood as systemic in nature, because it refers to Indigenous notions of the individual that are characterized by connectedness.

Family Resilience

Elders stressed the importance of family, talking about their own growing up, family support, identity, and role models. They shared childhood memories of traditions related to gardening, making a living off the land, connecting to the land, work ethic, crafts, and gender roles. Some elders talked about growing up both in cities and on farms or rural reservations. Recalling school or college, elders shared incidents of being teased or discriminated against, but also of being resilient. For example, one elder explained how his childhood memories of herding sheep helped him through school away from his family, and how his father’s professional accomplishments inspired him to complete college.

According to the elders, “strong families” were characterized by positive family relations that allowed for cooperation and togetherness, support, and child raising. Many comments focused on social support within the family and included practical support, such as teaching a professional skill or lending money, and emotional support, such as telling children to ignore name calling at school, or praying for a relative. Elders stressed the importance of families spending time together when they talked about “working as a family,” “knowing and/or being close to family members,” “eating with family,” “going on a family trip,” and “having good communication.” Some elders directly talked about family as being a strength or strategy to survive hard times. According to elders, families needed to be safe environments for children, and parents needed to protect their children in the home and in school by preventing bullying.

Elders described families in the past beyond the nuclear family and as the units where parents or relatives taught cultural knowledge, practical skills, and values, all of which contributed to the identity formation of the younger generation. All elders talked about the importance of teaching children and about how parents or other family members, such as grandparents, used to teach an array of life skills and values. These lessons included traditional identities (e.g., language, songs and stories, gender roles, work ethic, traditional crafts, gardening, knowledge of how to use the land, respect, responsibility through chores, family relations, how to pray), workforce skills, and support for education.

In telling their stories, elders talked about people who served as role models for them, about being role models themselves, and about the importance of role models. Most elders fondly remembered their grandparents, parents, or aunts. These relatives imparted knowledge and skills, including gardening, butchering, counseling others, being medicine men, and knowing traditions around birth and death. They also were remembered for having survived adversities and for being strong, hardworking, spiritual, healthy and long lived, knowledgeable of their people’s history, and an inspiration for getting a college degree. Several elders talked about serving or wanting to serve as role models for their foster children or grandchildren, and the need for youth to have elders as role models to teach them their Native language and cultural values, traditional knowledge and practices, and about historical trauma.

Community Resilience

Elders reflected upon community resilience as language, culture, and tradition, but some also pointed to social, political, and economic strategies of resilience. They saw how families and individuals practicing traditional land use, spirituality, and storytelling contributed to community resilience anchored in culture and traditions. Elders noted the potential of spirituality to bring communities together in ceremonies or churches. They considered storytelling a traditional resilience strategy that connected them to their grandparents and that could connect today’s youth to their history, culture, and community. One elder summarized this sentiment: “…to teach the next generation, go back to storytelling, sharing our stories that we know, that we remember. Teaching our language.” Elders described a level of community resilience that began with families and friends getting together and creating a community characterized by social support relationships. Community allowed for mutual support and the building of long-lasting connections. In urban contexts, where the support from family members or tribal programs was missing, elders talked about the importance of finding people who could be trusted to build new connections and support relationships.

On a more structured level, elders talked about urban community resources available to both residents in general and AIs in particular. They suggested seeking help from various resources, presented here in order of frequency mentioned: Social services, including food stamps, Alcoholics Anonymous, workshops, and shelters; educational resources in form of schools, community colleges, and The University of Arizona; and resources for AI/ANs, including local resources based on national institutions such as the Indian Health Service, the Indian Child Welfare Act, or Indian Centers. Elders stressed the TIC as an example of urban AI resilience. The Center provides an array of services for those going through hard times or new to town, and opportunities to connect, in particular for urban AI youth.

A few elders talked about the sovereignty status and resources held by tribes to provide educational funds, social services, and health programs. Elders wanted their tribal leaders, councils, and committees to advocate for their tribal members residing in urban settings.

DISCUSSION

The life narratives of urban AI elders offer insights into resilience strategies to cope with life stressors in the context of historical trauma. Elders shared multifaceted personal stories that presented the interconnectedness between historical trauma and resilience, and revealed that traditional cultural perceptions connected the present to the past, and individuals to families and communities.

Elders defined historical trauma in the context of events that their ancestors had endured, which resulted in multiple losses. The detrimental impact of boarding schools on families and communities (i.e., separating children from their families, and interrupting traditional parenting practices and the transmission of cultural knowledge and traditions) has been described in the literature on non-urban AIs (Brave Heart, 2003; Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Goodkind et al., 2012). These researchers understood that contemporary adversities were linked to past traumatic experiences, an insight that also was observed among AI/ANs (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Myhra, 2011) and AN elders (Wexler, 2013). Knowledge of their own and their ancestors’ experiences with historical trauma and losses had left the elders with yearning for the past and admiration for their ancestors. The latter sentiment was shared by urban AI/ANs in Myhra’s (2011) study that described how participants felt pride and understanding for their elders who had survived hardships. Elders described the historical trauma experienced by today’s youth as “broken families,” lamenting that youth did not understand historical trauma and needed to be taught about it. The generational gap observed in our study has been noted in the literature as “generational rift between elders and youth” (Goodkind et al., 2012, p. 1028), and other researchers have noted that differential understandings of culture between generations reflect a “need for more communication between generations” (Wexler, 2013, p. 17).

The elders’ narratives reflected the concept of historical trauma (Brave Heart et al., 2011) by giving glimpses of their and their ancestors’ lived experiences of colonization, and lived experiences of national policies and government practices aimed at assimilation. They also talked about the historical trauma response associated with unresolved historical grief as expressed in maladaptive behavior and health disparities. In elders’ stories, historical trauma seemed to be linked to the experiences of each person’s life in historical context; thus, the concept of historical trauma was simultaneously generic, yet fluid. As a contextualized, fluid concept, historical trauma can be understood as the lived experiences of past and present communities, families, and individuals. The importance of situating historical trauma experiences in their historical times––in line with Elder’s (2001) life course approach––has been expressed by Sotero (2006).

While our study approach separated historical trauma and resilience questions, the elders’ stories about historical trauma were accompanied by narratives of resilience and resilience strategies. This interweaving of historical trauma with resilience and resilience strategies is reported in the literature (Denhan, 2008; Goodkind et al., 2012). Denham (2008) elaborated how narratives of trauma, in addition to their contents, were framed and told in ways that promoted resilience. Taking a “strength-based perspective” (Denham, 2008), narratives emphasized how family members had successfully overcome challenges and remained strong, thus allowing listeners to internalize strategies of current or past family members. Narratives thus portray the individual strategies of the narrators, but also transmit family and cultural strategies (Denham, 2008; Kirmayer et al., 2012).

The elders in our study shared resilience strategies at the individual, family, and community levels. Their prevailing focus on individual resilience, expressed as personal responsibility and strength, was anchored in the context of history, family, and community. Previous studies confirmed the importance of personal strength for the concept of resilience (Goodkind et al., 2012, p. 1032). The contextualized, relational selves presented by the elders were cultural constructions of personhood (Kirmayer et al., 2009, 2012) that reflected traditional AI/AN perceptions of their places in the world. These cultural perceptions of the self “situate people as part of something larger” as expressed in “feeling grounded by their connection to values, orientation, knowledge, and sustaining practices of their traditions and cultures” (Wexler, 2013, p. 14).

Elders in our study talked about Indigenous identity as community resilience when they shared their childhood and youth stories, reflecting upon cultural knowledge, language, traditional practices, spirituality, and storytelling. The central importance of Indigenous identity for community resilience has been described in the literature (Cloud Ramirez & Hammack, 2014; Fleming & Ledogar, 2008; Goodkind et al., 2012; Grandbois & Sanders, 2012). Culture and identity, as well as family support and spirituality, as sources of resilience have been stressed in studies with AI elders (Grandbois & Sanders, 2009, 2012).

Located between the individual and community levels, the families described by the elders served connecting, supporting, and identity formation functions. As described in the literature, families play important roles in transmitting “cultural identity and collective memories to their children” (Denham, 2008, p. 298). Relationships to individual family members such as grandmothers are vital in Indigenous identity formation (Cloud Ramirez & Hammack, 2014).

The elders’ narratives reflected current concepts of resilience (Goodkind et al., 2012; Grandbois & Sanders, 2012; Kirmayer et al., 2011, 2012; Kirmayer et al., 2009; Ungar, 2012a, b; Wexler, 2013). The stories described resilience as a process in which individuals acted upon adversities by accessing various resources accessible in their social, cultural, and physical contexts. These resources differed depending on time in history and locality (i.e., rural or urban). Resources were available at individual, family, and community levels, thus reflecting Ungar’s (2008, 2011, 2012a, 2012b) social ecological definition of resilience. Individual resilience strategies drew from the family system in the form of teachings and guiding relationships, and also pursued meaning, strategies, and resources from cultural resources and Indigenous identities. Elders shared Indigenous concepts of community resilience in their stories by revealing notions of personhood where individuals were connected to past family members, the land, and the environment, with a high value placed on Indigenous languages, cultures, traditions, storytelling, spirituality, and identities. Connectedness with family members––difficult to maintain in urban settings––was replaced by newly created, mostly Indigenous family relationships and friendships. By interweaving stories of historical trauma and resilience, elders demonstrated their understanding of how historical traumatic events continued to impact contemporary AI/AN communities, families, and individuals. Their urging to teach youth about history and historical trauma to help overcome historical trauma responses falls in line with the call issued by Brave Heart and colleagues (2011) to confront and understand historical trauma in preparation for the undoing and final transcending of unresolved grief.

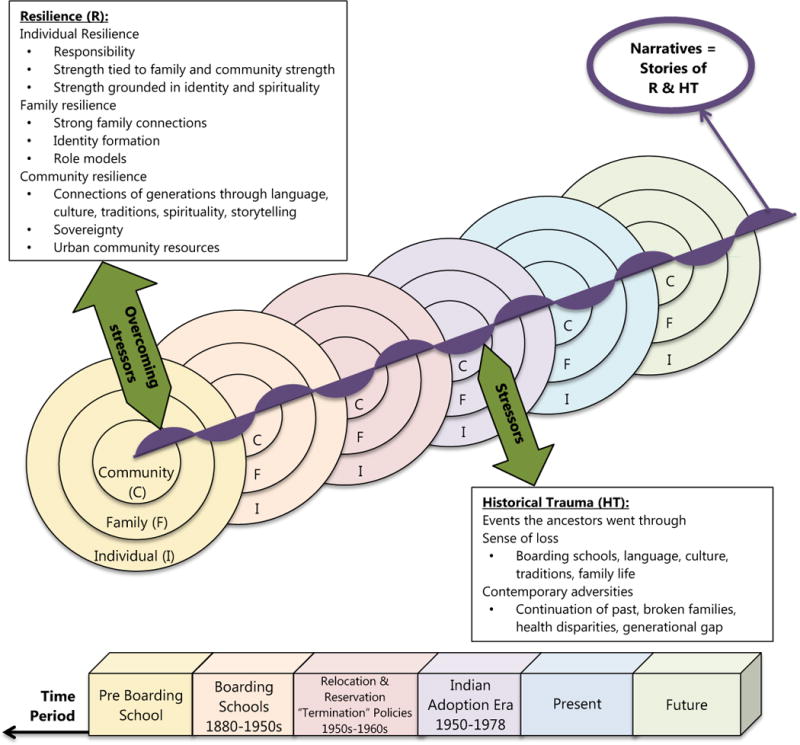

Based on our understanding of the elders’ stories, and supported by the literature on historical trauma and resilience, we introduce a strength-based explanatory model to illustrate that narratives link resilience with historical trauma (See Appendix B, Figure 1). Both historical trauma and resilience are made up of multiple levels, whereby the historical trauma and resilience of individuals are connected to the historical trauma and resilience of families and communities. Our conceptualization of resilience as taking a social ecological approach is supported in the literature (Grandbois & Sanders, 2012; Kirmayer et al., 2011, 2012; Kirmayer et al., 2009; Sotero, 2006; Ungar, 2008, 2012a, 2012b). Our model shows how both historical trauma and resilience are embedded in specific historical times (based on Myhra, 2011) which results in flexible perceptions of historical trauma and resilience. We visualize the continuity of both historical trauma and resilience, indicating how current and future generations can learn about historical trauma and prevent it from having continued negative impacts by engaging proactively in resilience strategies passed down through generations.

Limitations

The aim of this qualitative study was to understand, not to generalize. Our understanding of urban AI elders’ resilience strategies to cope with life stressors and historical trauma was intended to inform the development of a health promotion curriculum for urban youth and their families. In addition, the study’s findings also can contribute to theory development (Patton, 2002)––in this case, theories of AI resilience.

One limitation is that we did not analyze the elders’ narratives in the context of specific tribal affiliations. By not doing so, we may have overlooked specific tribal experiences and resilience strategies. We also acknowledge the limitation of segmenting the elders’ rich stories to discover themes and patterns without recounting the full stories. Our analysis employed Western-based qualitative analysis methods, while Indigenous approaches may have yielded different results. Finally, our study and manuscript work with complex concepts such as “culture” without offering critical definitions. To illustrate this point, it should be noted that, while “culture” can be supportive of resilience (Wexler, 2013), it also can have the opposite effect. For example, in their long-term, multidisciplinary study, Panter-Brick & Eggerman (2012) found that Afghan youth experienced cultural values both as protective resources that fostered resilience, and as causes of distress and suffering. Afghan youth strove to obtain the cultural value of a good education to overcome poverty; however, they also had to fulfill cultural expectations (e.g., marriage for girls, providing for the family for boys) that interfered with their education, thus curtailing an essential resilience strategy.

Implications for Public Health

Public health needs to prioritize participatory, strength-based approaches to health promotion in AI communities. Resilience interventions with a social ecological approach are grounded in local knowledge, values, and practices. They have the potential to support the immediate and long-term well-being of individuals, families, and communities. Our study and existing literature suggest that resilience and resilience strategies need to be addressed in the path of transcending historical trauma, as called for by Brave Heart et al. (2011).

As contemporary adversities of AI/ANs result from historical trauma experiences and continued discrimination, interventions need to take “a long-term approach to rebuild, repair and revitalize community strengths and institutions” (Kirmayer, Sehdev, Whitley, Dandeneau, & Isaac, 2009, p. 63) with a specific focus on community resilience. This focus on community interventions within an ecological framework has the potential to both address the underlying causes of contemporary adversities and “change social and economic policies and current distributions of power”––for example, at tribal, state, and federal levels (Goodkind et al., 2012). Kirmayer and colleagues (2009) already suggested types of interventions with examples to promote community resilience. The importance of community healing, along with individual and family healing, has been stressed in early research on AI/AN historical trauma (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998). Indigenous ceremonies, including healing ceremonies, are concrete examples of community resilience strategies (Brave Heart, 2003; Brave Heart & DeBruyn 1998). Culturally based community resilience interventions, however, can only occur in close collaboration and consultation with local community members, as the same cultural practices (e.g., language or spiritual traditions) that promote resilience may have been lost or nearly lost in the past due to forced assimilation. Knowing what cultural knowledge, values, and practices can and should be practiced or brought back will be key.

While historical trauma and resilience as lived experience may differ for each generation, strategies of resilience employed by earlier generations may be adopted by current generations. Contemporary identities need to be negotiated between generations. Nurturing mutual understanding and respect for what generations endure is a foundation for building resilience and breaking the cycle of historical trauma. Future studies should continue with intergenerational research among AIs, as exemplified by Wexler’s (2013) work with ANs.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Center for American Indian Resilience (CAIR), funded by the National Institute Of Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20MD006872. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We express our gratitude to Nancy Stroupe, MPH for helping during the beginning of the project, and to Tara Chico, MPH (Tohono O’Odham Nation) whose insights during the analysis process were appreciated. We are grateful to the Tucson Indian Center for partnering with the CAIR team, and to the elders for sharing their stories.

APPENDIX A

Table 1.

Coding Book

| Themes | Patterns |

|---|---|

| Category I: Historical Trauma | |

| Indigenous concepts | |

| Sense of loss | boarding school, broken families, loss of language, loss of traditions, removal from family, removal from land, yearning |

| Adversities | alcoholism/drugs, discrimination, generational gap, ill health, living conditions, loss of family member, lost voice, violence |

| Category II: Resilience | |

| Indigenous concepts | |

| Individual | know roots, participation, practicing spirituality, responsibility, strength, volunteerism |

| Family | family members as role models, growing up, positive family relations, safe environment for kids, teaching children |

| Community | culture/traditions/language, economic development, other community resources, sharing stories, sovereignty, spirituality, TIC, traditional land use |

| Youth | activities, education, get elders and youth together, know roots/know history |

APPENDIX B

Figure 1.

Stories of Resilience Model

Contributor Information

Kerstin M. Reinschmidt, Assistant Professor at the Mel & Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona.

Agnes Attakai, Navajo Nation, Arizona, and is Director of Health Disparities Outreach & Prevention Education at the Mel & Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona.

Carmella B. Kahn, Navajo Nation, Arizona, and is a doctoral student at the Mel & Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona.

Shannon Whitewater, Navajo Nation, Arizona, is an MPH student, and a Health Educator at the Mel & Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona.

Nicolette Teufel-Shone, Professor & Section Chair of the Family and Child Health Section at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public (CAIR).

References

- Anthony EJ. Children at high risk for psychosis growing up successfully. In: Anthony EJ, Cohler BJ, editors. The invulnerable child. New York: Guilford; 1987. pp. 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Daley CM, Nazir N, Kinlacheeny JB, Ashley A, Ahluwalia JS, Choi WS. Physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake among American Indians. Journal of Community Health. 2012;37:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9417-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9417-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MYH. The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MYH, Chase J, Elkins J, Altschul DB. Historical trauma among Indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):282–290. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628913. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MYH, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1998;8(2):60–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.5820/aian.0802.1998.60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud Ramirez L, Hammack PL. Surviving colonization and the quest for healing: Narrative and resilience among California Indian tribal leaders. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2014;51(1):112–133. doi: 10.1177/1363461513520096. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1363461513520096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham AR. Rethinking historical trauma: Narratives of resilience. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2008;45(3):391–414. doi: 10.1177/1363461508094673. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1363461508094673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran E. Healing the soul wound: Counseling with American Indians and other Native peoples. New York: Teachers College Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr Families, social change, and individual lives. Marriage & family review. 2001;31(1–2):187–203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J002v31n01_08. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming J, Ledogar RJ. Resilience, an evolving concept: A review of literature relevant to aboriginal research. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal & Indigenous Community Health. 2008;6(2):7–23. Retrieved from http://www.pimatisiwin.com/online/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Hess JM, Gorman B, Parker DP. “We’re still in a struggle”: Diné resilience, survival, historical trauma, and healing. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22(8):1019–1036. doi: 10.1177/1049732312450324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049732312450324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbois DM, Sanders GF. The resilience of Native American elders. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:569–80. doi: 10.1080/01612840902916151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01612840902916151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbois DM, Sanders GF. Resilience and stereotyping: The experiences of Native American elders. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2012;23(4):389–396. doi: 10.1177/1043659612451614. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1043659612451614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A, Allen A, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory principles. In: Minkler M, Wallenstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley; 2003. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn-John M. Concept analysis of Diné hozho: A Diné wellness philosophy. Advances in Nursing Science. 2010;33(2):113–125. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181dbc658. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181dbc658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, Williamson KJ. Rethinking resilience from Indigenous perspectives. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;56(2):84–91. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600203. Retrieved from http://publications.cpa-apc.org/browse/sections/0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, Williamson KJ. Toward an ecology of stories: Indigenous perspectives on resilience. In: Ungar M, editor. The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L, Sehdev M, Whitley R, Dandeneau SF, Isaac C. Community resilience: Models, metaphors and measures. Journal of Aboriginal Health. 2009;5(1):62–117. Retrieved from http://www.naho.ca/journal/2009/11/09/community-resilience-models-metaphors-and-measures/ [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhra LL. “It runs in the family”: Intergenerational transmission of historical trauma among urban American Indians and Alaska Natives in culturally specific sobrietymaintenance programs. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2011;18(2):17–40. doi: 10.5820/aian.1802.2011.17. http://dx.doi.org/10.5820/aian.1802.2011.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Urban Indian Family Coalition. A report to the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Seattle, WA: Author; 2011. Urban Indian America: The status of American Indian and Alaska Native children and families today. Retrieved from http://nuifc.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/NUIFC_Report2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Norris T, Vines PL, Hoeffel EM. The American Indian and Alaska Native population 2010–2010 Census Briefs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M. Understanding culture, resilience, and mental health: The production of hope. In: Ungar M, editor. The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147(6):598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotero MA. Conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2006;1(1):93–108. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1350062. [Google Scholar]

- Stumblingbear-Riddle G, Romans JS. Resilience among urban American Indian adolescents: Exploration into the role of culture, self-esteem, subjective well-being, and social support. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2012;19(2):1–19. doi: 10.5820/aian.1902.2012.1. http://dx.doi.org/10.5820/aian.1902.2012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel-Shone NI, Gamber M, Watahomigie H, Siyuja TJ, Jr, Crozier L, Irwin SL. Using a participatory research approach in a school-based physical activity intervention to prevent diabetes in the Hualapai Indian community, Arizona, 2002–2006. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11(E166):130397. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130397. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.130397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel-Shone NI, Siyuja T, Watahomigie HJ, Irwin S. Community-based participatory research: Conducting a formative assessment of factors that influence youth wellness in the Hualapai community. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1623–1628. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054254. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.054254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucson Indian Center. Elder healthcare report and recommendations. Tucson, AZ: Ridgewood Associates Public Relations, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work. 2008;38:218–235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl343. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. American Journal of Prthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Researching and theorizing resilience across cultures and contexts. Preventive Medicine. 2012a;55:387–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M, editor. The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. New York: Springer; 2012b. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0586-3. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Indian Health Institute, Seattle Indian Health Board. Community health profile: Tucson Indian Center. Seattle, WA: Urban Indian Health Institute; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.uihi.org/download/CHP_Tucson_Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Data derived from Population Estimates, American Community Survey, Census of Population and Housing, County Business Patterns, Economic Census, Survey of Business Owners, Building Permits, Census of Governments. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2015. State and County QuickFacts. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/04/0477000.html. [Google Scholar]

- Washburn WE. History of Indian-White relations. In: Sturtevant WC, editor. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 4. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1988. (Volume Ed.) (General Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L. Looking across three generations of Alaska Natives to explore how culture fosters Indigenous resilience. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2013;51(1):73–92. doi: 10.1177/1363461513497417. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1363461513497417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]