Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the effect of MHT on incident hypertension in the two Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) hormone therapy trials and in extended post-intervention follow-up.

METHODS

A total of 27,347 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years were enrolled at 40 US centers. This analysis includes the subsample of 18,015 women who did not report hypertension at baseline and were not taking anti-hypertensive medication. Women with an intact uterus received conjugated equine estrogens (CEE; 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; 2.5 mg/d) (n = 5994) or placebo (n = 5679). Women with prior hysterectomy received CEE alone (0.625 mg/d) (n = 3108) or placebo (n = 3234). The intervention lasted a median of 5.6 years in the CEE plus MPA trial and 7.2 years in the CEE-alone trial with 13 years of cumulative follow-up until September 30, 2010. The primary outcome for these analyses was self-report of a new diagnosis of hypertension and/or high blood pressure requiring treatment with medication.

RESULTS

During the CEE and CEE plus MPA intervention phase the rate of incident hypertension was 18% higher for intervention than for placebo (CEE: HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.09, 1.29; CEE plus MPA: HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.09, 1.27). This effect dissipated post-intervention in both trials (CEE: HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.94, 1.20; CEE plus MPA: HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.94, 1.10).

CONCLUSIONS

CEE (0.625 mg/d) administered orally, with or without CEE+MPA, is associated with an increased risk of hypertension in older postmenopausal women. Whether lower doses, different estrogen formulations, or transdermal route of administration offer lower risks warrant further study.

Keywords: hypertension, blood pressure, menopausal hormone therapy

INTRODUCTION

The effect of hormone therapy on the development of secondary hypertension in post-menopausal women remains controversial. Results from early clinical trials showed that post-menopausal hormone use had minimal or no effect on blood pressure [1], although one such trial showed that younger age was associated with a treatment-associated rise in systolic blood pressure [2, 3]. Results from retrospective and observational studies have been inconsistent with respect to associations between hormone therapy and blood pressure [4–6]. However, a recent large cohort study showed a positive association between hormone therapy use and hypertension diagnosis that was more pronounced with younger age [7]. Recent data from a large randomized trial also suggest that dose and route of administration may matter; in that trial both lower oral dose and transdermal route of estrogen were not associated with an increase in blood pressure [8].

The Women’s Health Initiative included 2 randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of hormone therapy (conjugated equine estrogens [CEE] in women with prior hysterectomy and CEE plus medroxyprogesterone [MPA] in women with intact uteri) in relation to chronic disease incidence, including cardiovascular events and markers of cardiovascular health, among post-menopausal women. Both arms of the trial showed an approximate 1 mm Hg increase in systolic blood pressure at year one among women who received hormones, which persisted during follow-up [9, 10]; this finding has since been confirmed by subsequent analysis [11]. Diastolic blood pressure did not differ at year 1 between intervention and placebo groups in the CEE-alone or CEE plus MPA trials.

WHI results indicated that age and time since menopause onset may be important factors when interpreting the effect of hormone use on cardiovascular health. Women who took hormones in the CEE plus MPA trial had no increase in coronary events if they were within 10 years of the onset of menopause (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.90) but a significant increase if they were ≥20 years past menopause (HR=1.52) [12]. In the CEE-alone trial, women aged 50–59 who were assigned to estrogen were less likely to experience a coronary event than women assigned to placebo (HR 0.60) [13], and this effect persisted through the post-trial follow-up period as initially and later reported (HR=0.59, HR=0.65) [13, 14]. On the other hand, in both trials, younger and older women had similar treatment-associated increases in the risk of stroke. Thus, we sought to determine the effect of CEE-alone and CEE + MPA on the development of hypertension in the WHI during the intervention and post-intervention phases, with attention to possible differences by age group or years since menopause onset. The effect of hormone therapy on rates for self-report of a physician’s diagnosis of “hypertension or high blood pressure requiring pills” as an endpoint has not previously been reported and is our primary research question.

Our use of self-reported treatment for hypertension, which is included in some guidelines as an appropriate indicator for hypertension [15], complements findings of a WHI publication on the effect of hormone therapy and mean blood pressure [11]. A definition of hypertension based on high blood pressure measured on a single annual occasion is not consistent with clinical practice and may overestimate incidence. Consequently, we investigate this composite endpoint (self-report of hypertension or blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg) as a secondary endpoint.

WHI post-trial results for hypertension diagnoses have not been previously reported, and age may be an important factor determining cardiovascular risks and benefits associated with HT use. We report data on hypertension diagnosis for the intervention and post-intervention periods for both the E+P and E-alone arms of the WHI Trial. This preplanned analysis had three objectives: (1) to assess the effect of CEE alone and CEE+MPA, compared with placebo, on incident diagnoses of hypertension during the intervention; (2) to assess the long-term (post-intervention) effects of the CEE alone and CEE+MPA interventions on hypertension diagnoses; (3) to determine if age or time since menopause onset modified the effects of hormone therapy on incident hypertension during the intervention and post-intervention periods.

Methods

Details of the study design have previously been published [13, 16]. Briefly, postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years were recruited at 40 US clinical centers between 1993 and 1998 for the CEE trial and the CEE plus MPA trial. Women were eligible if they were not taking hormone therapy, did not have a history of breast cancer or other cancer within 10 years (except non-melanoma skin cancer), and had an anticipated survival of at least 3 years. Study participants provided informed consent in a document approved by local institutional review boards and were randomly assigned to receive oral CEE, 0.625 mg/d (Premarin; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Madison, NJ) or CEE plus 2.5mg oral MPA (Prempro, Wyeth Ayerst, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), depending on hysterectomy status, or matching placebo. A total of 10,739 women were randomly assigned to receive CEE-alone or placebo, and 16,608 to receive CEE plus MPA or placebo. Participants were excluded if they had self-reported at baseline ever taking pills to treat high blood pressure or hypertension, or were using anti-hypertension medications at their baseline medication inventory. The remaining participants were included in the analysis of the CEE-alone trial (n=6342) and CEE plus MPA trial (n=11,673).

The post-intervention phase began on July 8, 2002 for the CEE plus MPA trial and on March 1, 2004 for the CEE trial and ended on March 31st, 2005 for both trials’ in-clinic visit assessments, resulting in 2.6 years and 1.0 years of post-intervention follow-up, respectively. Subsequent participant follow-up through September 30, 2010 required additional written consent that was obtained on 83% and 78% of surviving participants in the CEE+MPA and CEE trials, respectively.

Incident hypertension

Incident hypertension, the primary endpoint, was defined as self-report of treated hypertension and collected semiannually. Specifically, participants were asked, “Since the date given on the front of this form, has a doctor prescribed any of the following pills or treatments?” The choices included “pills for high blood pressure or hypertension.”

Those who self-reported a prior history of treated hypertension or who were using antihypertensive medications at baseline were not eligible to be classified with incident disease and were excluded. A subsequent analysis was carried out to confirm the robustness of the primary endpoint with incident hypertension defined as either self-report of treated hypertension or blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg at least one of the annual follow-up clinic visits; blood pressure was measured at annual follow-up visits through the protocol-specified termination date (March 31, 2005). Analyses of this secondary composite endpoint are presented in the Supplemental Digital Content. To investigate the whether the effect of hormone therapy on incident hypertension (primary endpoint) dissipated after the intervention had ended, summary statistics are also presented for the post-intervention period that includes extended follow-up. Blood pressure was not collected during extended follow-up, so a similar analysis for the composite endpoint could not be performed for extended follow-up.

Statistical analysis

In both hormone therapy trials, incidence of hypertension within the two randomization groups was compared using failure-time methods and the intention-to-treat principle. All participants who did not self-report a prior diagnosis of treated hypertension at baseline and were not taking anti-hypertensive medications were included in the analyses according to their randomized group until their last follow-up information. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated from Cox regression models, stratified by age group, race/ethnicity and randomization assignment in the concurrent WHI dietary modification trial. Analyses were performed for two time phases: the intervention phase (from randomization until July 7, 2002 for CEE+MPA and until February 29, 2004 for CEE alone); and the post-intervention phase (from July 8, 2002 for CEE+MPA and from March 1, 2004 for CEE alone), until end of extended follow-up (September 30, 2010 for the primary endpoint in both hormone-therapy trials), or until planned close out (March 31, 2005 for the composite endpoint in both hormone-therapy trials) for the composite endpoint. Date of incident hypertension was defined as the date of self-report of treated hypertension. Event times during the intervention phase were censored at date of death, last follow-up, or termination of the intervention phase (on July 7, 2002 for CEE+MPA and February 29, 2004 for CEE alone), whichever occurred first. Participants were included in post-intervention phase incidence analyses if they were alive, in follow-up, and had not developed hypertension by termination of the intervention.

In subgroup analyses, interactions were tested between randomization assignment and ten baseline characteristics within the primary Cox model, expanded to include the designated baseline factor, randomization assignment, and interaction term(s). Participants with missing values were omitted from the corresponding analysis.

In sensitivity analyses, the influence of non-adherence to protocol-assigned treatment was examined by censoring events after participants first became non-adherent (i.e., stopped taking study pills, took <80% of study pills, or started non-study menopausal hormone therapy). Time-varying weights, which were inversely proportional to the estimated probability of continued adherence, were included in the proportional-hazards models to adjust for changes in the distribution of sample characteristics during follow-up.

No adjustment for multiple testing was made. For each time phase, one interaction at most was expected to be significant by chance alone. All analyses were done with SAS version 9.3, and figures were drawn with R 2.15. All p-values are two-sided and p-values of 0·05 or less were regarded as significant at the 0·05 level. The WHI study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00000611.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographic and risk factor characteristics of participants in the CEE and CEE plus MPA trials are shown in TABLE 1. Of 12 variables examined, only one showed a statistically significant difference between intervention and placebo groups. In the CEE trial, women with high cholesterol by self-report or medical history were somewhat more likely to have received placebo.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the WHI CEE Trial (N=6342) and CEE+MPA Trial (N=11673) by randomization arm.

| CEE Trial | CEE+MPA Trial | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Active (N=3108) |

Placebo (N=3234) |

P-Valuea | Active (N=5994) |

Placebo (N=5679) |

P-Value | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Age group (y) | 0.67 | 0.70 | ||||||||

| <55 | 491 | 15.8 | 500 | 15.5 | 855 | 14.3 | 812 | 14.3 | ||

| 55-<60 | 632 | 20.3 | 636 | 19.7 | 1414 | 23.6 | 1322 | 23.3 | ||

| 60-<70 | 1357 | 43.7 | 1462 | 45.2 | 2662 | 44.4 | 2491 | 43.9 | ||

| ≥70 | 628 | 20.2 | 636 | 19.7 | 1063 | 17.7 | 1054 | 18.6 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.58 | 0.60 | ||||||||

| White | 2470 | 79.5 | 2566 | 79.3 | 5132 | 85.6 | 4869 | 85.7 | ||

| Black | 303 | 9.7 | 344 | 10.6 | 286 | 4.8 | 282 | 5.0 | ||

| Hispanic | 218 | 7.0 | 224 | 6.9 | 349 | 5.8 | 303 | 5.3 | ||

| American Indian | 20 | 0.6 | 17 | 0.5 | 19 | 0.3 | 27 | 0.5 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 54 | 1.7 | 42 | 1.3 | 128 | 2.1 | 127 | 2.2 | ||

| Unknown | 43 | 1.4 | 41 | 1.3 | 80 | 1.3 | 71 | 1.3 | ||

| Years since menopause (y) | 0.47 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| < 5 | 236 | 9.1 | 234 | 8.4 | 1045 | 19.4 | 965 | 18.4 | ||

| 5 - <10 | 333 | 12.8 | 324 | 11.7 | 1107 | 20.5 | 1125 | 21.4 | ||

| 10 - <15 | 440 | 16.9 | 475 | 17.1 | 1164 | 21.6 | 1091 | 20.8 | ||

| ≥15 | 1594 | 61.2 | 1741 | 62.8 | 2074 | 38.5 | 2065 | 39.4 | ||

| Bilateral oophorectomy | 1098 | 38.0 | 1234 | 41.1 | 0.61 | 16 | 0.3 | 15 | 0.3 | 0.98 |

| HRT use status | 0.59 | 0.44 | ||||||||

| Never used | 1577 | 50.7 | 1605 | 49.7 | 4382 | 73.2 | 4199 | 74.0 | ||

| Past user | 1101 | 35.4 | 1184 | 36.6 | 1188 | 19.8 | 1112 | 19.6 | ||

| Current user | 430 | 13.8 | 442 | 13.7 | 420 | 7.0 | 367 | 6.5 | ||

| Baseline blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg | 630 | 20.3 | 636 | 19.7 | 0.55 | 1059 | 17.7 | 1027 | 18.1 | 0.56 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 0.32 | 0.70 | ||||||||

| <25 | 793 | 25.6 | 808 | 25.1 | 2074 | 34.8 | 2004 | 35.5 | ||

| 25 - <30 | 1116 | 36.1 | 1219 | 37.9 | 2189 | 36.7 | 2054 | 36.4 | ||

| ≥30 | 1183 | 38.3 | 1189 | 37.0 | 1704 | 28.6 | 1588 | 28.1 | ||

| Smoking status | 0.71 | 0.61 | ||||||||

| Never | 1547 | 50.3 | 1582 | 49.5 | 2907 | 48.9 | 2784 | 49.6 | ||

| Past | 1170 | 38.1 | 1250 | 39.1 | 2341 | 39.4 | 2159 | 38.5 | ||

| Current | 356 | 11.6 | 366 | 11.4 | 694 | 11.7 | 665 | 11.9 | ||

| Treated diabetes (pills or shots) | 133 | 4.3 | 128 | 4.0 | 0.52 | 135 | 2.3 | 129 | 2.3 | 0.94 |

| High cholesterol (self-report or mx) | 266 | 8.6 | 335 | 10.4 | 0.01 | 495 | 8.3 | 500 | 8.8 | 0.29 |

| Mean (SD) age (y) | 62.6 | (7.2) | 62.7 | (7.3) | 0.39 | 62.4 | (7.0) | 62.5 | (7.1) | 0.33 |

| Mean (SD) systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125.6 | (15.7) | 125.2 | (15.7) | 0.35 | 123.8 | (16.0) | 124.2 | (16.1) | 0.17 |

| Mean (SD) Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.2 | (8.7) | 75.0 | (8.8) | 0.33 | 74.6 | (8.7) | 74.7 | (8.6) | 0.51 |

Test of association based Chi-squared test (categorical variables) or t-test (continuous variables).

Women in the CEE-alone differed from women in the CEE plus MPA trials. Women in the CEE trial were more likely to be members of racial/ethnic minority groups, to have a greater number of years since menopause onset, to use hormone therapy at or prior to baseline, to be overweight or obese, and to have diabetes than women in the CEE plus MPA trial.

Among women that remained at risk for incident hypertension during the post-intervention phase, baseline characteristics remained balanced between randomization groups (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

CEE Trial

Intervention Phase

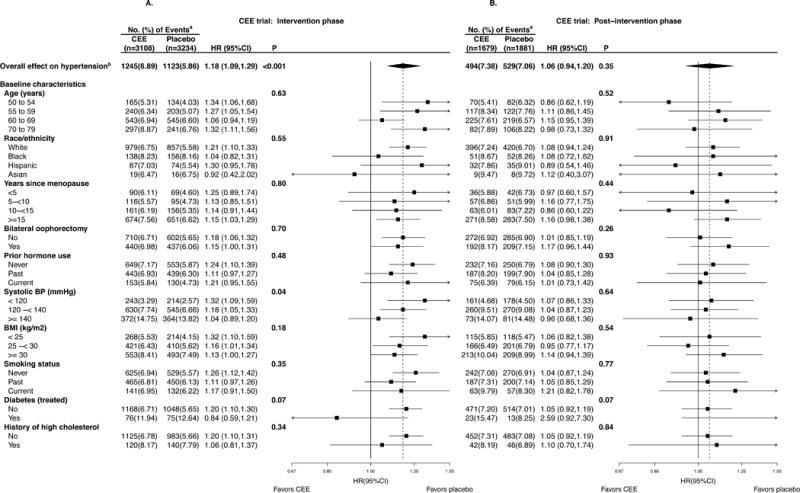

Figure 1A displays the effect of CEE on the primary endpoint of incident hypertension (self-report of physician-prescribed pills for “high blood pressure or hypertension”) during the intervention phase. Incident hypertension was 18% higher among women assigned to CEE alone than among those assigned to placebo (HR [95% CI] 1.18 [1.09, 1.29]), with an absolute excess risk of 103 additional diagnoses of hypertension per 10000 person-years. The average treatment-associated increase in systolic blood pressure was 0.68 (0.02, 1.33) mmHg at year 1 (p=0.04). CEE did not increase average diastolic pressure in the overall cohort.

Figure 1.

A & B. Subgroup analysis by a forest plot of HRs, CEE versus placebo, of incident hypertension during the intervention phase (randomization through February 29, 2004; left panel) and post-intervention phase (March 1, 2004 through September 30, 2010; right) for the CEE trial. CEE indicates conjugated equine estrogens; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; P, p-value for the significance test of the main effect or test of interaction/trend.

a Percentages are annualized.

b Incident hypertension defined as self-report of hypertension.

Of ten baseline characteristics, only baseline systolic blood pressure modified the risk of developing hypertension while taking estrogen (Figure 1A). Women with a baseline systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg who took estrogen were 32% more likely to report a new hypertension diagnosis or new blood pressure medication use than those who took placebo (HR 1.32, p-interaction = 0.04), and the effect of CEE significantly decreased with increasing baseline BP. The HR for the overall effect on the secondary composite endpoint of self-report of hypertension, or high blood pressure was 1.18 (1.10, 1.26), with similar influence by subgroup (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2a).

Among participants in the youngest age group (age 50–54 years), the absolute treatment-associated increase in systolic blood pressure at year one was 2.05 mm Hg (0.38, 3.72). In this age group, women with intact ovaries were more likely to report a new hypertension diagnosis or new blood pressure medication use while taking estrogen than were those with bilateral oophorectomy (HR=1.56 [1.16, 2.09] v. HR=0.83 [0.52, 1.30], respectively), although the three-way interaction was not significant (p-interaction=0.09).

Post-intervention Phase

Figure 1B displays the effect of CEE-alone after the intervention period through planned close-out; the median post-intervention follow-up was 5.8 (IQR, 5.1–6.0) years. The treatment-associated risk of hypertension was no longer statistically significant during post-intervention (HR 1.06 [0.94, 1.20], p=0.35), and there was no significant effect modification of the CEE-hypertension association by any of the baseline factors examined, including baseline systolic blood pressure.

Similar results were observed for the secondary endpoint of self-report of treated hypertension or high blood pressure (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2b).

E+P Trial

Intervention Phase

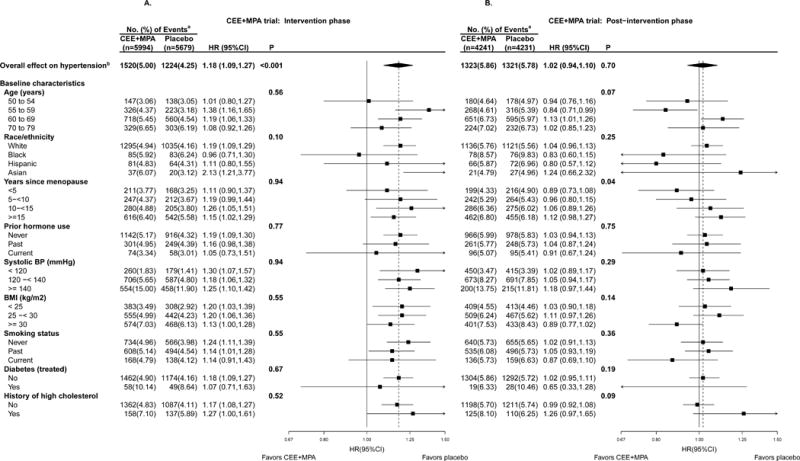

Figure 2A displays the effect of CEE plus MPA on incident hypertension during the intervention phase. The rate of incident hypertension (self-report of physician-prescribed pills for high blood pressure or hypertension) was 18% higher for women assigned to CEE+MPA compared with those assigned to placebo (HR 1.18 [1.09, 1.27]), with an absolute excess risk of 75 additional diagnoses of hypertension per 10000 person-years. The average treatment-associated increase in systolic blood pressure was 0.71 (0.24, 1.18) mm Hg at year 1, with no detected effect on diastolic pressure. None of the examined baseline factors significantly modified the association between CEE plus MPA and either incident hypertension or blood pressure change. The HR for the overall effect on the secondary composite endpoint of self-report of hypertension, or high blood pressure was 1.11 (1.05, 1.17), with similar influence by subgroup (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3a).

Figure 2.

A & B. Subgroup analysis by a forest plot of HRs, CEE+MPA versus placebo, of incident hypertension during the intervention phase (randomization through July 7, 2002; left panel) and post-intervention phase (July 8, 2002 through September 30, 2010; right) for the CEE+MPA trial. CEE indicates conjugated equine estrogens; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; P, p-value for the significance test of the main effect, or test of interaction/trend.

a Percentages are annualized.

b Incident hypertension defined as self-report of hypertension.

Post-intervention Phase

The risk of incident hypertension was no longer statistically significant during the post-intervention phase (HR 1.02 [0.94, 1.10], P=0.70 (Figure 2B); the median post-intervention follow-up was 2.8 (IQR, 2.8-2.8) years. However, the treatment-associated risk of hypertension was positively associated with years since menopause onset (p-interaction=0.04); women randomized to CEE+MPA closer to menopause onset were less likely to develop hypertension during the post-intervention period. Similar results were observed for the secondary endpoint of self-report of treated hypertension or high blood pressure (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3b).

Sensitivity Analyses

Censor for noncompliance with study pills

When we accounted for adherence to study pills during the trial (censoring participants who stopped taking study pills, who took less than 80% of prescribed doses, or began taking non-study hormone therapy), the effect of hormone therapy on hypertension increased in both trials (CEE, HR 1.25 [1.12, 1.40]; CEE plus MPA, HR 1.25 [1.13, 1.38]). In addition, the effect modification of the CEE-hypertension association by baseline systolic blood pressure became more marked, with HRs of 1.57 (1.18–2.09), 1.18 (1.01–1.39), and 1.03 (0.85–1.26) for women with systolic pressures of <120, 120-<140, and ≥140 mmHg, respectively.

Exclude participants with baseline blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg

Excluding participants with baseline blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg had little influence on the effect of hormone therapy on our primary or composite endpoints. In the CEE trial, the HR increased modestly to 1.26 (1.14–1.39) and 1.23 (1.13–1.33) for the primary and composite endpoints, respectively. For the CEE+MPA trial, the HR changed slightly to 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) and 1.13 (1.06, 1.21), respectively.

Examine effect over time of MHT on incident hypertension

Risk modestly increased with duration of MHT use. Specifically, the HR during 0-<2, 2-<4 and ≥4 years after randomization into the CEE trial were 1.03 (0.87, 1.21), 1.17 (1.01, 1.36), and 1.29 (1.14, 1.46), respectively (p-trend = 0.03). Likewise, the HR for the CEE+MPA trial were 1.10 (0.96, 1.27), 1.17 (1.03, 1.32), and 1.25 (1.10, 1.42), respectively (p-trend = 0.12).

Discussion

The WHI provides evidence from a large randomized trial that hormone therapy, both CEE plus MPA and CEE alone, increases the risk of developing hypertension in menopausal women and that this risk dissipates after discontinuation of hormone therapy.

The effect of hormone therapy on blood pressure was greatest for women who took CEE alone and had baseline systolic blood pressures of less than 120 mmHg, and diminished among women with higher systolic blood pressure, although this trend could be attributed to chance alone.

Significant increases of systolic blood pressure among older postmenopausal women randomized to 0.625 mg/d of CEE have been consistently observed in large randomized trials. The HERS trial (n=2763) showed a 2 mmHg increase in mean systolic blood pressure associated with oral CEE+MPA use [17]. The WHI trials corroborated the unfavorable effect of CEE, with (n=16808) or without MPA (n=10739), on mean systolic blood pressure, with increases of 1–2 mmHg for both WHI trials [11]. Our current study shows that these ostensibly small increases in mean blood pressure directly translate into increased risk of hypertension, and are therefore clinically relevant.

Importantly, some evidence suggests that an alternate dose, formulation, and route of administration for estrogen may not detrimentally influence blood pressure. In KEEPS, a four-year randomized trial of 727 younger postmenopausal women, transdermal estradiol or lower doses of oral CEE (0.45 mg/d) taken with cyclical micronized progesterone did not increase blood pressure [8]. Similarly, smaller randomized trials of oral estradiol, ELITE (n=643)[18] and EPAT (n=222)[2], found no increase in systolic blood pressure. However, the PEPI trial (n=875)[1] reported that CEE (0.625mg/d), with or without MPA, also did not significantly increase blood pressure in younger women, raising the possibility that the lack of association in the estradiol trials was due not to the hormone formulation or dose but to the younger age of the study participants. However, there was no significant effect modification of the hormone therapy-blood pressure relation in our study. Also, CEE, with or without MPA, increased the incidence of stroke in the WHI trials across all age groups [12]. Moreover, in a large population-based study, oral but not transdermal hormone therapy was also associated with increased stroke risk regardless of age [20].

The renin-angtiotensin system (RAS) is dose-dependently activated in women who take estrogen containing oral hormone therapy or oral contraceptives, and may be related to its first-pass hepatic metabolism. First-pass hepatic metabolism leads to increased production of CRP and angiotensin II and a reduction in IGF-I, processes implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertension [19]. Indeed, in both the CEE and CEE+MPA trials of the WHI, the treatment was associated with these biomarker changes [20] [21, 22] [20]. Increases associated with CEE in particular may be caused by its ability to induce a molecular variant of angiotensinogen or renin substrate [23]. Interestingly, one small randomized trial found that, unlike oral hormone therapy, transdermal hormone therapy had no effect on RAS activity in normotensive postmenopausal women [24].

Increases in blood pressure, however, do not occur in all women who take estrogen. Some studies suggest that the effects of estrogen on the RAS may be genetically mediated, with some women less able to compensate for the dose-dependent increase in RAS activation that results in higher blood pressure [25, 26]. Genetic susceptibility may provide a way of identifying those for whom use of oral estrogen will raise blood pressure.

We found an overall increase in risk of hypertension in women who were randomized to CEE plus MPA, but unlike the women randomized to CEE alone, we did not find that baseline blood pressure modified that risk. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the MPA may have overridden the dose effect of the estrogen in participants who had lower baseline systolic blood pressure. MPA is known to have beneficial effects on the vascular endothelium of post-menopausal women taking estrogen [27, 28].

Although risk of incident hypertension somewhat increased with follow-up during the intervention phase, complementing an earlier report of the non-diminishing influence of CEE, with or without MPA, on mean systolic blood pressure (11), we found that the risk of hypertension associated with use of CEE or CEE plus MPA dissipated during the post-intervention phase.

This study has some limitations. It is possible that women who were randomized to CEE or CEE plus MPA may have been more likely to have had more clinic visits than women who were randomized to placebo. A greater frequency of visits increases the opportunity of capturing a hypertension diagnosis, although the significant increase in mean systolic blood pressure, measured annually at protocol specified visits, did not diminish during the intervention period (11).

As previously reported [13, 16], participants who were randomized to hormones were less likely to be compliant than those randomized to placebo, which could have appreciably biased risk estimates towards the null. However, our adherence analysis indicated that this was unlikely, as risk estimates that accounted for compliance were only modestly increased.

Conclusion

These results indicate that 0.625 mg/d of CEE, with or without MPA, administered orally to older postmenopausal women caused an increased risk in hypertension that dissipated after the intervention ended. When applying the new clinical practice guidelines [29], clinicians should also consider use of MHT, and CEE in particular, when screening for secondary hypertension. The possibility that transdermal, lower dose, or non-CEE hormone formulations may be less likely to increase blood pressure or stroke risk, warrants further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

WHI Investigators and Study Participants

The authors thank the WHI investigators, staff, and the trial participants for their outstanding dedication and commitment.

Short List of WHI Investigators

Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller

Clinical Coordinating Center: Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg.

Investigators and Academic Centers: (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker

For a list of all the investigators who have contributed to WHI science, see: https://www.whi.org/researchers/Documents%20%20Write%20a%20Paper/WHI%20Investigator%20Long%20List.pdf.

Funding/Support: The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C, and HHSN268201600004C. Wyeth Ayerst donated the study drugs.

Role of the Sponsor: The Women’s Health Institute (WHI) Project Office at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the Sponsor, had a role in the design and conduct of the study and interpretation of the data. Decisions concerning the above, as well as data collection, management, analysis, review or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication resided with committees comprised of WHI investigators and included NHLBI representatives. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: Dr. Kaunitz receives grant funding from Pfizer, TheraputicsMD, and Bayer. He also receives royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Womack receives grant funding from Bayer.

Listing of Supplemental Digital Content:

MENO-D-17-00264_Supplemental Digital Content.pdf

Contributor Information

Yael Swica, Department of Medicine, Division of Family and Community Medicine.

Michelle P. Warren, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medicine.

JoAnn E. Manson, Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Aaron K. Aragaki, Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Shari S. Bassuk, Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Daichi Shimbo, Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology.

Andrew Kaunitz, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Jacques Rossouw, Division of Cardiovascular Sciences, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Marcia L. Stefanick, Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford Women and Sex Differences in Medicine (WSDM) Center Stanford University School of Medicine.

Catherine R. Womack, Department of Preventive Medicine and Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center.

References

- 1.Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. JAMA. 1995;273(3):199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner AZ, et al. Postmenopausal oral estrogen therapy and blood pressure in normotensive and hypertensive subjects: the Estrogen in the Prevention of Atherosclerosis Trial. Menopause. 2005;12(6):728–33. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000184426.81190.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Air A, Lip GY, Beevers DG. Hormone replacement therapy. Attitudes of women should be considered. BMJ. 1994;8(7):192. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6948.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lip GY, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and blood pressure in hypertensive women. Journal of Human Hypertension. 1994;8(7):491–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scuteri A, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and longitudinal changes in blood pressure in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(4):229–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-4-200108210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren MP, et al. Quality of life and hypertension after hormone therapy withdrawal in New York City. Menopause. 2013;20(12):1255–63. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31828cfd3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu CL, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy is associated with having high blood pressure in postmenopausal women: observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harman SM, et al. Arterial imaging outcomes and cardiovascular risk factors in recently menopausal women: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):249–60. doi: 10.7326/M14-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manson JE, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(6):523–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsia J, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and coronary heart disease: the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(3):357–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimbo D, et al. The effect of hormone therapy on mean blood pressure and visit-to-visit blood pressure variability in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2014;32(10):2071–81. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000287. discussion 2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manson JE, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson GL, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1701–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaCroix AZ, et al. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golden SH, et al. Health disparities in endocrine disorders: biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors–an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):E1579–639. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossouw JE, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair GV, et al. Pulse pressure and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease. Chest. 2005;127(5):1498–506. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodis HN, et al. Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashraf MS, Vongpatanasin W. Estrogen and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2006;8(5):368–76. doi: 10.1007/s11906-006-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossouw JE, et al. Inflammatory, lipid, thrombotic, and genetic markers of coronary heart disease risk in the women’s health initiative trials of hormone therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(20):2245–53. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitteri SJ, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen and progestin effects on the serum proteome. Genome Med. 2009;1(12):121. doi: 10.1186/gm121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katayama H, et al. Application of serum proteomics to the Women’s Health Initiative conjugated equine estrogens trial reveals a multitude of effects relevant to clinical findings. Genome Med. 2009;1(4):47. doi: 10.1186/gm47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barton M, Meyer MR. Postmenopausal hypertension: mechanisms and therapy. Hypertension. 2009;54(1):11–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikawa J, et al. Different effects of transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy on the renin-angiotensin system, plasma bradykinin level, and blood pressure of normotensive postmenopausal women. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(7):744–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan NM. Hypertension induced by pregnancy, oral contraceptives, and postmenopausal replacement therapy. Cardiol Clin. 1988;6(4):475–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulatero P, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensinogen gene polymorphisms are non-randomly distributed in oral contraceptive-induced hypertension. J Hypertens. 2001;19(4):713–9. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koh KK, et al. Vascular effects of synthetic or natural progestagen combined with conjugated equine estrogen in healthy postmenopausal women. Circulation. 2001;103(15):1961–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.15.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakatsuki A, et al. Effect of medroxyprogesterone acetate on vascular inflammatory markers in postmenopausal women receiving estrogen. Circulation. 2002;105(12):1436–9. doi: 10.1161/hc1202.105945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whelton PK, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.