INTRODUCTION

Since 2015, five states and a growing number of municipalities have enacted Tobacco 21 policies to raise the minimum age of tobacco purchase to age 21 years. Tobacco 21 policies are expected to prevent or delay youth tobacco use initiation by further limiting access to tobacco, especially from older peers,1 thereby reducing tobacco use2 and improving health for young adults.1,3,4

Although most adults, including smokers, support Tobacco 21 policies in the U.S.,5–8 less is known about adolescent and young adult support, despite evidence that youth who support tobacco control legislation are more likely to comply.9 A recent cross-sectional study demonstrated that a majority of youth support Tobacco 21, with policy support associated with having no intention to use tobacco among users and nonusers.10 Yet little is known about trends in youth support for Tobacco 21 over time. Tobacco 21 support is examined in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents and young adults from 2014 to 2017, including young smokers most affected by such policies, before and after state legislative actions.

METHODS

Tobacco 21 policy support is reported by quarter with data from a rolling cross-sectional, nationally representative phone (cell and landline) survey of individuals aged 13–25 years (n=11,847, American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate 3=21%),11 administered from June 2014 to June 2017. Respondents who agreed or strongly agreed with the following statement were considered to be in favor of Tobacco 21: The legal age to buy tobacco cigarettes should be increased from 18 to 21. The sample was weighted to be representative of the U.S. population of individuals aged 13–25 years. The IRB of the University of Pennsylvania reviewed and approved the survey. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 13.

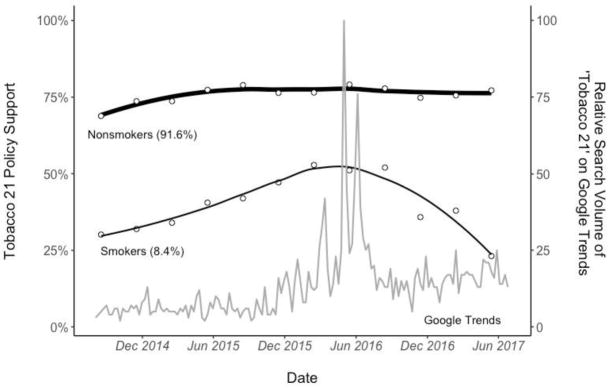

Weekly U.S. Google Trends data are reported for searches including Tobacco 21 as a measure of public engagement with the issue. These data reflect relative search volume over the study period, scaled from 0 to 100, and are available from google.com/trends.

RESULTS

A majority of individuals aged 13–25 years (69.8%) favored raising the minimum age of tobacco purchase to age 21 years across the 3-year study period (Table 1). Most individuals aged 13–25 years (84.4%) were not current smokers, having not smoked a tobacco cigarette in the past 30 days. Whereas 73.5% of current nonsmokers endorsed the policy, 49.8% of current smokers were supportive of Tobacco 21. Among smokers and nonsmokers, individuals aged 13–17 years were most supportive of the policy (79.9%), relative to individuals aged 18–20 (61.4%) and 21–25 years (65.0%).

Table 1.

Weighted Demographic Distribution of Support for Tobacco 21 Policy (N=11,774)

| Demographic | Percentages supporting raising tobacco cigarette purchasing age to 21 years (95% CI) | Weighted percentages of survey respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (13–25 years) | 69.8 (68.8, 70.8) | 100 |

| Age groups | ||

| 13–17 | 79.9 (78.6, 81.1) | 38.2 |

| 18–20 | 61.4 (59.3, 63.4) | 23.9 |

| 21–25 | 65.0 (63.1, 66.8) | 37.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 74.8 (73.4, 76.1) | 49.1 |

| Male | 65.2 (63.7, 66.6) | 50.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 73.4 (71.3, 75.3) | 21.3 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 66.0 (64.6, 67.4) | 51.4 |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 77.1 (74.6, 79.4) | 14.1 |

| Other/more than one | 72.0 (69.2, 74.7) | 13.2 |

| Tobacco cigarette use | ||

| All current non-smokers (no past 30-day use) | 73.5 (72.5, 74.5) | 84.4 |

| Age 13–20 years | 75.8 (74.7, 76.9) | 57.0 |

| Age 21–25 years | 68.8 (66.7, 70.7) | 27.4 |

| All current smokers (past 30-day use) | 49.8 (46.8, 52.8) | 15.6 |

| Age 13–20 years | 40.1 (35.8, 44.5) | 5.2 |

| Age 21–25 years | 54.7 (50.8, 58.5) | 10.4 |

Note: Percentage totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Among the group aged 13–20 years, the age group personally subject to the policy, nonsmokers demonstrated strong support (75.8%) for Tobacco 21 across the study period, whereas just 40.1% of those most affected—current smokers aged 13–20 years—supported the policy. Among this subgroup, policy support by calendar quarter demonstrated a curvilinear trend, increasing since mid-2014, peaking at >50% support in the first two quarters of 2016, and subsequently returning to lower levels (Figure 1). Among current nonsmokers aged 13–20 years, policy support was more consistent over time, reaching a plateau at just >75% in support of Tobacco 21.

Figure 1.

Weighted Tobacco 21 policy support among individuals aged 13–20 years over time, by smoking status and Google Trends relative search volume for “Tobacco 21” over time (2014–2017).

Notes: The black lines are Loess curves illustrating temporal trends in weighted mean Tobacco 21 policy support (left y-axis) by quarter among smokers aged 13–20 years (thin line) and nonsmokers aged 13–20 years (thick line). The grey line illustrates variation in the weekly relative search volume for “Tobacco 21” on Google Trends (right y-axis).

Google Trends relative search volume, a possible indicator of greater public engagement with the issue of Tobacco 21, peaked in May 2016, as decline in policy support among smokers aged 13–20 years began (Figure 1). Spikes in Google Trends search volume around this time suggest more public engagement with Tobacco 21 as policies were enacted, including in California, the most populous state, on May 4, 2016.

DISCUSSION

Most adolescents and young adults are nonsmokers and favor Tobacco 21 policies in the U.S. Recently, support has declined only among smokers younger than age 21 years following policy-relevant events. Resistance stimulated by salient policy threats may have played a role in the decline in support among smokers aged 13–20 years. A key limitation of this study is that Tobacco 21 policy support was measured with a single item, which specifically asks about raising the minimum age of legal access for tobacco cigarettes. Strengths of the study include measuring policy support over 3 years among a nationally representative sample of youth and young adults. Overall, most youth and young adults support Tobacco 21 policies. While youth nonsmokers have exhibited high and stable levels of Tobacco 21 support, support among young smokers has declined as of mid-2016.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH and the Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products under Award Number P50CA179546. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age of Legal Access to Tobacco Products. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. https://doi.org/10.17226/18997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessel Schneider S, Buka SL, Dash K, et al. Community reductions in youth smoking after raising the minimum tobacco sales age to 21. Tob Control. 2015;25(3):355–359. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052207. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meernik C, Baker HM, Lee JGL, et al. The Tobacco 21 movement and electronic nicotine delivery system use among youth. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20162216. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2216. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winickoff JP, Gottlieb M, Mello MM. Tobacco 21 an idea whose time has come. N Engl J Med. 2015;370(4):295–297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314626. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1314626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winickoff JP, McMillen R, Tanski S, Wilson K, Gottlieb M, Crane R. Public support for raising the age of sale for tobacco to 21 in the United States. Tob Control. 2016;25(3):284–288. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052126. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morain SR, Winickoff JP, Mello MM. Have Tobacco 21 laws come of age? N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1601–1604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1603294. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1603294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King BA, Jama AO, Marynak KL, Promoff GR. Attitudes toward raising the minimum age of sale for tobacco among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(4):583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JGL, Boynton MH, Richardson A, Jarman K, Ranney LM, Goldstein AO. Raising the legal age of tobacco sales: policy support and trust in government, 2014–2015, U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(6):910–915. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Howard KA, et al. Attitudes toward anti-tobacco policy among California youth: associations with smoking status, psychosocial variables and advocacy actions. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(6):751–763. doi: 10.1093/her/14.6.751. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/14.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai H. Attitudes toward Tobacco 21 among U.S. youth. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170570. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0570. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: AAPOR; 2016. www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. [Google Scholar]