Introduction

Work‐related stress is an example of a psychosocial risk factor that has become of interest in today's ever‐demanding, fast‐paced, and globalized society, although its link to adverse health and in particular coronary heart disease (CHD) is incompletely understood. In this review, we will outline the need to identify novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the potential role of psychosocial risk factors, such as work stress; describe the theoretical frameworks by which work stress may influence health; review evidence provided by observational studies for the link between work stress and CHD; and explore potential mechanisms that may play a role in this relationship and evaluate the evidence for potential therapeutic interventions in this area.

The Need to Identify Novel Risk Factors for CVD

CVDs are the leading cause of death in both men and women of every major ethnic group in the United States, of which CHD is the most prevalent.1 In 2014, >600 000 Americans were estimated to have a new coronary event and ≈300 000 had a recurrent event.2 Between 2013 and 2030, medical costs of CHD are projected to increase by ≈100%,3 highlighting a growing health and socioeconomic problem. Nevertheless, CHD may be preventable,4 and preventative strategies are cost‐effective.5 Identification of at‐risk groups and appropriately addressing risk factors form the cornerstone of successful management, and can be achieved using multivariable risk‐prediction algorithms,6, 7, 8, 9 of which the most widely used in clinical practice are the Framingham‐based models. These scores assign weights to different levels of traditional risk factors, such as age, total cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure, which are combined to generate an absolute probability of developing CHD within a specified time frame. Framingham‐based risk prediction models are well established, practical, and easy to use, supported by large amounts of data and in most cohorts discriminate risk well, after calibration, where necessary.10 Nevertheless, Framingham‐based scores are limited by incorporating a limited number of risk factors, such as age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and smoking, which have been identified from historically based population studies.11 Alternative tools to assist in risk prevention have been developed, including the American Heart Association's Life's Simple 7, which identifies a construct of ideal cardiovascular health characterized by ideal health behaviors: nonsmoking, body mass index (BMI) <25 kg/m2, physical activity at goal levels, pursuit of a diet consistent with current guideline recommendations, and ideal health factors (untreated total cholesterol <200 mg/dL, untreated blood pressure <120/<80 mm Hg, and fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL).12 Although these individual concepts are well supported in the literature, the Life's Simple 7 focuses exclusively on “conventional cardiovascular risk factors,” which in themselves account for between 58% and 72% of all incident cases of CHD.13 Alternative nonconventional risk factors may account for some of this gap and are becoming increasingly important, particularly as the effects of previously implemented attempts at managing conventional risk factors are being seen. For example, a recent time trend analysis showed that patients presenting to the catheterization laboratory with CHD had better blood pressure and lipid profiles between 2006 and 2010, compared with between 1994 and 1999,14 which may reflect improved uptake of primary and secondary preventative strategies, such as smoking cessation.15 There was also a higher proportion of patients taking risk‐modifying cardiovascular medication.16 Furthermore, in one study of young adults hospitalized with their first myocardial infarction, <25% would have qualified for lipid‐lowering therapy based on guidelines available at the time,17 further demonstrating the limitation of current risk‐based algorithms. Thus, there is a need to identify and account for novel risk factors not currently accounted for in traditional risk prevention models. The increasing awareness of social and psychological determinants of health18 has opened up novel avenues in which the contribution of these risk factors to the cause, development, and outcome of CHD19, 20, 21 is becoming increasingly understood.

One review concluded “there is strong and consistent evidence of an independent causal association between depression, social isolation and lack of quality social support and the causes and prognosis of CHD” and that the “increased risk contributed by these psychosocial factors is of similar order to more conventional CHD risk factors such as smoking, dyslipidemia and hypertension.”22 Similarly, in their review of the literature, Krantz and McCeney found compelling evidence to suggest an association between acute and chronic stress, depression, social support, and socioeconomic status with the development of CHD,23 which was in keeping with the findings of Strike and Steptoe in their review of epidemiologic data.24

Evidence linking work stress and the development of CHD remains unclear however. Of the workforce, 10% to 40% struggle with work‐related stress, and at least one third of these experience severe chronic psychosocial stress.25 In one national study performed in France, up to 2% of a working population were affected by illnesses attributable to work‐related stress, which cost society up to 1975 million Euros.26 It is, therefore, important to examine this potential association in greater depth, particularly because work‐related stress is potentially modifiable.

Theoretical Frameworks Linking Work Stress to CHD

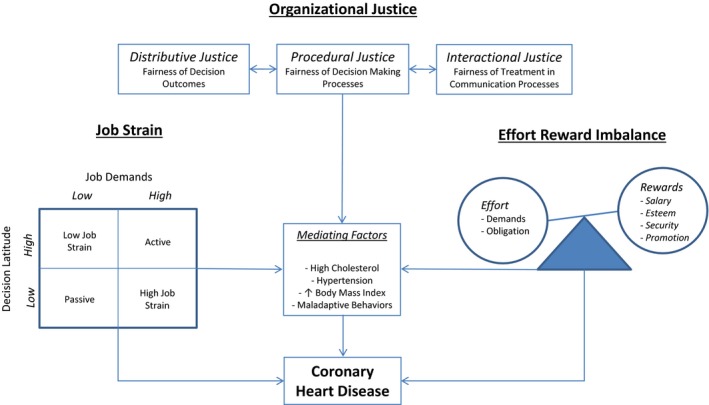

Evaluating “work stress” as a potential risk factor for CHD is challenging, given its subjectivity and the difficulty associated with synthesizing its significant components into comparable metrics. Social scientists have tackled this issue by constructing simplified frameworks by which a seemingly abstract concept, such as work stress, can be appreciated in an objective way. Investigators have since adopted these frameworks in their studies and in doing so have been able to generate useful comparisons that help determine the role work stress plays in CHD. In one of these frameworks, work stress can be characterized from the perspective of “job strain,” as per the job strain model, also known as the demand‐control model 27, 28 (Figure 1). This states that work associated with high psychological demands, such as intense and time‐critical tasks, and low control in areas such as decision authority, skill discretion, and learning opportunities is associated with high job strain27 and, in turn, high work stress. Several studies that have demonstrated an association between high job strain and an increased risk of CVD have shown that both high demands and low control are required to convey increased risk,27, 28, 29 whereas others have shown that low job control was more important than high job demand and is itself an independent predictor of CVD risk.30, 31, 32 There remains much controversy in the literature as to whether the relationship between job demand and control is additive or multiplicative, or if there is a buffering effect. In the latter, once levels of job control reach or exceed a certain threshold, the deleterious effects of demands are supposedly negated, although to date the precise relationship has not yet been clarified.33, 34, 35 Furthermore, a third component of the job strain model has been suggested (namely, social support in the workplace),36 which evaluates the contribution of support provided by one's colleagues and supervisors in the workplace. Once again, the buffer theory postulates that social support above a certain threshold level protects against the adverse effects of high job strain.34, 37

Figure 1.

Outline of the “Job Strain,” “Effort‐Reward Imbalance,” and “Organizational Justice” psychosocial models underlying the potential relationship between work‐related stress and coronary heart disease. Individuals with high job strain, effort‐reward imbalance, or organizational injustice may be at an increased risk of coronary heart disease directly or through mediating factors, such as hypertension, high cholesterol, or maladaptive behaviors.

The effort‐reward imbalance model (Figure 1) centers on the idea that the balance between one's perceived or actual effort into a particular job with one's actual or perceived rewards in terms of salary, recognition, and opportunities for career progression will influence one's risks for adverse health outcomes.38, 39 Although studies have shown an association between job strain and CVD mortality,40 evidence linking job effort‐reward imbalance to CVD mortality has been more sparse. Furthermore, studies that have been able to show an association have typically shown that, of the 2 constituent parts, low reward is the more important predictor of events.31 Another component of this model, personality traits, such as overcommitment, are seldom evaluated in work stress related studies, nor is their precise role, interactive or otherwise, clearly defined in the literature.41

Further research into work stress has led to the development of a third framework, known as the organizational justice model 42 (Figure 1). This model operates under the precept that justice is a fundamental value to the organization of society and to individual social interactions,43 and enduring perceived unfairness within the workplace can contribute to work stress.44 The model consists of 3 separate entities: distributive justice, which refers to the fairness associated with decision outcomes and the distribution of resources that may be tangible, such as pay, or intangible, such as praise; procedural justice, which is linked to distributive justice in that it relates to the fairness of the processes that lead to outcomes, such that when individuals believe they have a voice in the process or that these processes are consistent, accurate, and without bias, procedural justice is enhanced; and interactional justice, which, in turn, is linked to procedural justice and relates to informational justice, which focuses on explanations provided to people as to why certain procedures were used, and interpersonal justice, which reflects the degree to which people are treated with politeness, dignity, and respect by those performing procedures. The organizational justice model was developed later, and it is, therefore, less well established than the job strain and effort‐reward imbalance models; it has been examined in fewer studies. Although these models integrate and combine multiple different facets of working life, they remain limited in that they cannot account for all possible psychosocial and biological factors that may coexist and contribute to work stress and its relationship with CHD and adverse health in general. The precise interplay of extraneous psychosocial and biological factors with work stress and CHD is challenging to encapsulate in the form of descriptive models, which are designed to help simplify seemingly abstract and potentially subjective concepts into understandable and comparable constructs. Further investigation is required to better delineate these relationships. This review focuses on the 3 aforementioned models of work stress and does not evaluate the individual role of other work‐related factors, such as working shift patterns, whose relationship with CHD may be as important or potentially even more so than that of the 3 models evaluated.

Work Stress and CHD

We searched PubMed for potentially relevant articles published from January 1, 1970, through December 31, 2017, using the following key search terms: work stress, occupational stress, job stress, coronary artery disease, ischemic heart disease, and CVD. Searches were enhanced by scanning bibliographies of identified articles, and relevant articles were selected for review. Studies included for selection in this review required the following criteria: characterization of work stress using at least 1 of the 3 aforementioned established and validated work‐stress models (namely, the job strain, effort‐reward imbalance, and organizational justice models); defined outcomes of incident CHD/ischemic heart disease, characterized by angina or myocardial infarction, or of mortality related to CHD; provided a quantitative estimate and confidence interval (CI) of relative risk for incident CHD or CHD mortality and used a prospective causative cohort study design, because randomized controlled trials are not practical for this study question and prospective cohort studies represent the next best level of evidence and can allow inference of causality. Cross‐sectional and case‐control studies were excluded, as were studies that evaluated the impact of multiple individual isolated facets of the work environment, such as emotional demands, role clarity, career possibilities, and working overtime. Although they relate to adverse psychosocial elements of the working environment, and some have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of CHD,45 they do not encapsulate work‐related stress per se as a wider construct in the same ways that the 3 models selected for this review do. Indeed, work stress can be linked to a wide variety of psychosocial risk factors, some of which may coexist with work stress, but may not necessarily correlate with work‐related stress incurred on a day‐to‐day basis, or form an acceptable measurable synthesis of its relevant constituent parts. Working long hours, for example, has been shown to be associated with CHD,46 but individuals working long hours, or shift work, may not necessarily have work stress. Similarly, the authors of the job strain model stated that “cardiovascular risk results not from a single factor, but from the joint effects of the psychological demands of the work situation and the range of decision‐making freedom with respect to task organization and skill usage,”27 suggesting an understanding that work stress cannot be usefully characterized by focusing on individual work‐ related factors. The purpose of the current review was to examine the relationship between work stress in of itself, as a broad construct, synthesizing multiple relevant, yet unique, aspects of working life and CHD and not to investigate all individual psychosocial elements related to the working environment.

Often, separate articles were identified that presented data from the same study cohort (eg, with different periods of follow‐up or event rates). In these cases, unless the independent or dependent variables were significantly different, only the study presenting the most comprehensive data was included. Articles containing no original data, including reviews and meta‐analyses, were also excluded to avoid redundancy, particularly because those identified47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 included cohort studies that were individually selected for this review. A further issue with meta‐analyses for work stress is that concepts, such as job strain, effort‐reward imbalance, and organizational injustice, are typically characterized in a median or quartile split across the population investigated. As Burr et al outlined in their Letter to the Editor, whether certain individuals are identified as having job strain, and therefore have work stress, depends on who else is in the sample.53 This is problematic when work demand, control, and other work environment related characteristics vary between jobs and across countries. If the prevalence of job strain varies between populations and is inherently dependent on the distribution of demands and control within that population, combining data from different populations as part of a meta‐analysis can become challenging. This is highlighted in a review by Szerencsi et al, in which the authors showed that studies undertaken in the United States yielded ≈ 26% lower estimates compared with studies conducted in Scandinavian countries when determining the relative risk of CVD using the job strain model.54

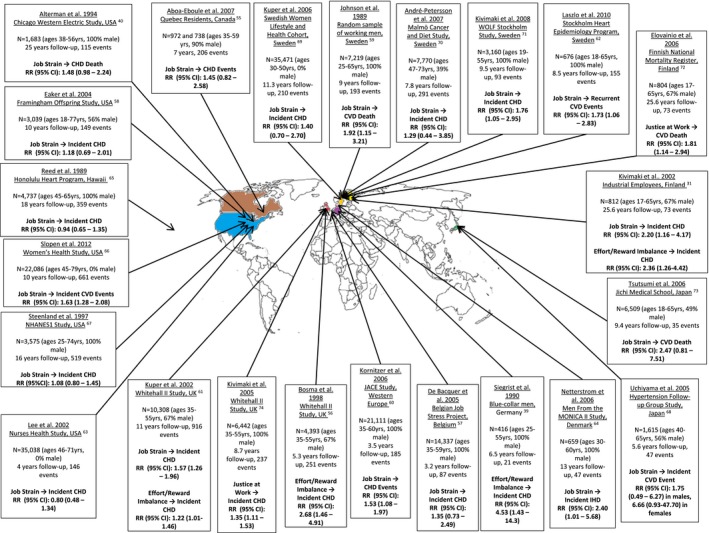

Figure 2 highlights the countries from which the 23 prospective cohort studies31, 39, 40, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74 that satisfied our inclusion criteria were performed and summarizes the estimate of risk (relative risk and CI) for incident CHD/CVD death associated with work stress in each study. Where studies provided a multivariable adjusted estimate of risk, this was preferentially included over an unadjusted estimate. All studies identified were undertaken in industrialized economically developed nations from North America, Western Europe, Scandinavia, and Japan. These nations would likely lend themselves to broad similarities in the types of jobs their populations do and have democratic political systems that would likely result in greater oversight and regulation of working environments and individual worker rights. As such, the results generated by these studies are likely to represent select populations in which working life is relatively more homogeneous compared with that found in nations with developing economies and alternative political systems. Thus, the results obtained from the studies included in this review may not necessarily be generalizable to workers in other nations, highlighting the need for further studies to be performed in different regions of the world. In addition, the lack of studies performed in developing nations with emerging economies and distinct social and cultural norms skews our understanding of work stress and its implications on CHD and adverse health. Studies performed in developing nations would enrich our understanding of this question and may allow the development of newer frameworks that factor in other aspects of working life and society not included in established models. Furthermore, studies from developing nations may uncover unique methods that local populations use to help mitigate work stress that could, in turn, help in the development of novel interventions that may be useful in managing work stress and its adverse health consequences.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the global distribution of prospective cohort studies evaluating the potential association between work‐related stress and coronary heart disease (CHD) or cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality. Twenty‐three prospective cohort studies were identified up until December 2017. Studies that provided a quantitative estimate of the association between work stress and incident CHD or CVD events/mortality and characterized work stress using the job strain, effort‐reward imbalance, or organizational injustice model were included. CI indicates confidence interval; IHD, ischemic heart disease; JACE, Job Stress, Absenteeism and Coronary Heart Disease In Europe study; MONICA, Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; and RR, relative risk.

Among the 23 studies identified, 17 evaluated work stress through the “job strain” framework only, 2 made use of the “effort‐reward imbalance” framework only, 2 evaluated both models separately, and 2 evaluated the organizational injustice model. Fourteen studies evaluated incident CHD or ischemic heart disease as their primary outcome, whereas the remaining 9 evaluated the incidence of CVD events or death. Eleven studies found no significant association between work stress and incident CHD/CVD. Among the 12 that did find an association, the relative risk (95% CI) for the association between work stress and incident CHD varied between 1.22 (1.01–1.46) and 4.53 (1.43–14.3), whereas that for the association between work stress and CVD events and death varied between 1.53 (1.08–1.97) and 1.92 (1.15–3.21). Both studies evaluating the organizational justice model found a significant association between work stress and incident CHD or CVD death, as did all 4 studies using the effort‐reward balance model, whereas of the 19 studies using the job strain model, 8 found a positive relationship. Thus, almost as many studies found an association between work stress and CHD as those that did not, and although one study demonstrated a >4‐fold increase in risk of incident CHD in patients experiencing work stress, the great variability in the results from the studies reflects differences in study design, number of patients included, follow‐up duration, and definitions of the exposures and outcomes. Several of these studies used CVD as the outcome of interest, which includes non–CHD‐related pathological conditions, such as cerebral vascular disease, which makes direct comparisons between studies difficult. Along the same lines, studies that evaluated CVD or CHD events and death look at “hard” outcomes that are easier to define accurately than more subjective definitions of CHD, such as a history of new‐onset chest pain consistent with angina, with the former definition likely to generate more conservative estimates of risk. Using different outcome variables defined in different ways raises difficulties when trying to compare and/or combine results from individual studies. Furthermore, the absence of randomization of the exposure variable in all the studies leads to problems with confounding and makes it difficult to derive a causal relationship between work stress and CHD with certainty. In addition, the studies included in this review represent a relatively homogeneous group and share many similarities in study design, in part because they are all prospective causative studies, but also because the nature of this particular study question is limited in the number of study designs it can lend itself to. Important differences in sample size, demography, length of follow‐up, and which exposure and outcome variables were used are highlighted in Figure 2. Herein, we outline some additional key issues related to study design that we believe are best illustrated through critiquing the 2 studies by Kuper et al61 and Kivimaki et al,31 which both included an assessment of the job strain and effort‐reward imbalance model, and are therefore more comprehensive studies that collectively highlight important methodological considerations common to all studies included in this review.

The Whitehall Study was one of the earlier cohorts to be evaluated for the relationship between work stress and CHD, and in one study, Kuper et al examined this association among 10 308 (67% men, aged 35–55 years) civil servants in London, England.61 This study followed a prospective cohort design in which subjects completed questionnaires at baseline (1985–1988) and on 2 subsequent follow‐up visits (1989–1990 and 1991–1993) consisting of questions asking about job control, job demand, and social support at work. In addition, questions derived from the previously validated Rose Questionnaire75 were used to assess for new angina or severe pain across the chest, a new diagnosis of ischemic heart disease, or any coronary event. The subjects’ managers also completed a questionnaire at baseline, providing an independent assessment of employee job strain. The investigators demonstrated that men and women with low job control had a higher risk for newly reported CHD at follow‐up compared with those with high control and that the odds ratio (95% CI) between men and women did not vary significantly (1.55 [1.20–2.01] versus 1.74 [1.15–2.64]). Furthermore, the investigators found that low job control had a cumulative effect on newly reported CHD rates, with subjects with low control on both follow‐up occasions having the highest odds of new CHD (odds ratio, 1.93 [95% CI, 1.34–2.77]). This association could not be explained away by employment grade or conventional CVD risk factors. A dose‐response relationship between job strain and the relative risk for acute myocardial infarction has been demonstrated in other studies.31, 76 Last, there was no significant association between job demand and social support in the work environment with newly reported CHD.

The previously described study highlights some of the design characteristics and methodological issues commonly encountered by other studies included in Figure 2. Although this study included a relatively large sample size (it was overall the sixth largest study included in this review; the largest study included 35 471 subjects, whereas 6 studies included <1000 subjects) and used a prospective design, one of its major limitations relates to the generalizability of the results. The British civil servants included in this study comprise “white collar” workers and are not comparable to manual laborers working in “blue collar” jobs. Moreover, the outcomes used in this study were subjectively determined by each employee and may correlate poorly to actual CHD, a problem encountered in other studies using a survey‐based approach to quantify outcomes. Studies relying on objective determinants of the outcome variable, such as myocardial infarction, identified from clinical records may arrive at more accurate conclusions, particularly because subjects who report experiencing job strain may have an inherent disposition making them more likely to report physical symptoms, such as chest pain/tightness, that may have organic causes but could also represent a psychosomatic process. All studies included in Figure 2 also made use of written surveys and/or direct in‐person interviews with employees and sometimes managers as well when characterizing work stress as the exposure variable. This poses another problem because not only does this method involve a subjective component that may be influenced by the interpretation of each question and the interviewing style of the questioner, among other factors, but there is also a possibility of responder bias. Those subjects who choose to participate in studies by responding to surveys, taking part in interviews, and then engaging with follow‐up are likely to be systematically different to those who do not respond or follow up, who may in general be less health conscious or too “stressed” at work to find time to participate in studies. A unique quality of this study was that the investigators evaluated the cumulative effect of job stress with an independent assessment of the impact that work stress had on CHD at multiple follow‐up points. There was also an independent assessment of job strain provided by questionnaires answered by managers as well as a subjective assessment of job strain completed by employees. Although these correlated poorly with each other (correlation coefficient, 0.41), both measures were associated with newly reported CHD, demonstrating that objective measures of work strain may be as important as those reported by the individual workers.

Other problems related to the studies included in Figure 2 relate to the fact that previous studies have shown that psychosocial stressors have a tendency to coexist and cluster such that individuals from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds tend to also have poorer social support and education levels as well as a higher prevalence of conventional CVD risk factors and certain “maladaptive” psychological traits24 compared with their counterparts from higher socioeconomic status backgrounds. Thus, when one social factor, such as higher socioeconomic status, is shown to be associated with lower rates of CHD,77 it can be challenging to determine if any coexisting variable is, in fact, playing a role, and if so, to what extent. Randomization is a useful technique in experimental studies that can balance covariates between groups exposed and not exposed to the variable of interest, although to date no randomized trial has been published evaluating the relationship between work stress and CHD, likely because of the practical difficulty of “assigning” a group to work stress. As such, a significant problem with the studies included in this review is discriminating whether work stress itself is responsible for the identified effect on CHD. Part of the increased risk of CHD in individuals from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds has been attributed to low control in the workplace.78 In another study that included >2000 Finnish men, those in the lowest socioeconomic status quintile, determined by income, had an age‐adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) for cardiovascular mortality of 2.66 (1.25–5.66) compared with those in the highest socioeconomic status quintile.79 This reduced to a hazard ratio of 1.71 (95% CI, 0.76–3.86) when depression and psychosocial factors, such as social support, were controlled for, suggesting that clustered psychosocial risk factors incrementally influence risk of disease and, in their absence, socioeconomic status in itself may not be associated with CVD. Adjusting for covariables can be a useful way to unpick these associations. This was illustrated in another study by Johnson et al,59 in which the authors evaluated the relationship between job strain and CVD death and controlled for confounding biological variables, such as known CVD risk factors, and psychosocial risk factors, such as social isolation, and were still able to demonstrate a significant association. Although adjusting for covariates can seem helpful in proving or disproving an independent risk factor–disease association, it can mask the true role of some factors that may, in fact, have mediating roles or act synergistically with other factors, the studying of which may provide greater insight into the precise mechanisms underpinning the relationship between work stress and CHD.

In our second study, Kivimaki et al31 examined the impact of work stress on CHD among 812 (67% men) Finnish industrial employees, including managers, other office staff, skilled workers, and semiskilled workers, all of whom were free of CVD at baseline. A major strength of this study was the inclusion of a wide diversity of occupational groups enhancing the generalizability of the findings, unlike the Whitehall study, which included a homogeneous group of “white collar” civil servants. The outcome assessed was CVD mortality anytime between 1973 and 2001, and it was determined from Finnish National Mortality Registries. The authors found that, after adjustment for age and sex, employees with high job strain and high effort‐reward imbalance had a relative risk (95% CI) of 2.20 (1.16–4.17) and 2.36 (1.26–4.42) for CVD mortality, compared with those with low job strain and low effort‐reward imbalance, respectively. These ratios remained significant after adjusting for occupational grade and behavioral risk factors, including negative affectivity, defined as a predisposition to respond to questionnaires negatively, which may erroneously inflate any observed associations. Low job control predicted CVD mortality before, but not after, adjustment, and neither high job demand nor high job effort predicted CVD mortality. This latter finding highlights the previously stated contention put forth by the conceivers of the job strain model that “cardiovascular risk results not from a single factor, but from the joint effects of the psychological demands of the work situation,”27 underscoring the fact that work stress, and in turn CHD, cannot be usefully predicted by focusing on its individual factors but rather the sum of its consistent parts.

A unique facet of the study by Kivimaki et al31 was the fact that blood pressure and serum cholesterol were measured at follow‐up after 5 years and BMI was measured after 10 years. High job strain was associated with increased serum cholesterol at 5 years’ follow‐up, and high effort‐reward imbalance was associated with increased BMI at 10 years’ follow‐up. These results suggest a potential, and plausible, mechanism for the relationship between work stress and CHD and thus conventional CVD risk factors, such as high cholesterol and hypertension, could be integrated into a partial mediation model (Figure 1). These findings could also support the incorporation of work‐stress models into conventional CHD risk prediction algorithms by linking work‐related stress with our knowledge about biological risk factors and their associations with inflammation80, 81 and endothelial dysfunction82, 83, 84, 85 that form the pathological basis of CHD.

In addition to the study by Kivimaki et al,31 others have also shown an association between effort‐reward imbalance and the incidence of CHD,38, 56, 78 but compared with studies evaluating job strain, these remain few. A potential explanation for this is that the job strain model has been longer established, is given more weight, and is thus investigated more frequently. Also, high job effort and high job demand, each of which individually contribute to the synthesis of work stress in their respective models, may be viewed as similar constructs, and indeed in the study by Kivimaki et al,31 some of the questions relating to job effort were identical to those relating to job demand. Some investigators may, therefore, not perceive these 2 work models to be distinct and would not want to reduce the sensitivity of detecting an effect between work stress and CHD by duplicating or reusing potential survey questions in an attempt to capture a measure of both models. Instead, they may choose to only study one model and choose the more well‐established and frequently studied job strain model. Only 2 studies included in Figure 2 evaluated the organizational injustice model, one of which was based from the Whitehall Cohort.74 This study also used surveys to characterize organizational injustice and used medical records to identify new definite angina and myocardial infarction as well as CHD death. The study showed a significant association with level of justice at work and incident CHD, even after adjusting for conventional CVD risk factors. Similarly, significant results were obtained in the study of Elovainio et al,72 which also evaluated justice at work, this time using a national mortality register to identify cases of CVD death, suggesting that the organizational injustice model, as an independent index of work stress, may also be used to predict CHD.

Of the 23 studies included in this review, 11 evaluated samples consisting of 100% men, whereas 1 study evaluated 90% men and a further 4 studies evaluated 67% men. Among these 16 studies, 11 found a significant association between work stress and CHD, whereas among the 11 studies consisting of 100% men, 7 showed a significant relationship. The strongest relationship was demonstrated in the study by Siegrist et al, in which effort‐reward imbalance was associated with a relative risk of 4.53 (95% CI, 1.43–14.3) for incident CHD,39 although this was one of the smaller studies included in this review, with 416 participants. Although there are studies that fail to show a significant relationship between work stress and CHD, overall there seems to be a trend favoring an association and the strength of this relationship appears to be in the region of an increased risk of 30% to 50%, although there is some variability. Among the 3 studies including 100% women, only 1 demonstrated a significant relationship between work stress and CHD, with job strain being associated with a relative risk of 1.63 (95% CI, 1.28–2.08) for CVD events,66 which also included stroke. The 2 studies that did not show a relationship between work stress and CHD were the 2 largest studies included in this review, both of which had sample sizes >35 000 and focused specifically on incident CHD, as opposed to non‐CHD CVD outcomes as well. Thus, the link between work stress and CHD among women has not been consistently demonstrated, although there is likely insufficient evidence in this area and further studies evaluating the relationship between work stress and CHD in women are required. The discordance in results between men and women may be related to the fact that CVD affects women later in life, possibly even after they have completed their “working lives.” Also, Orth‐Gomer et al demonstrated that psychosocial risk factor burden and resources at home may have a stronger contribution to health in women compared with men,86 and as such work stress may have a comparatively lesser role in determining health outcomes in women. There was also sparse information provided on the engagement in part‐time work in the studies included in this review, which may be more frequent in the female population and may also contribute to how work stress may be a less important psychosocial risk factor among women. There is also some evidence suggesting that there are sex‐based differences in the experiences of stress that could lead to differences in the response to surveys.87

Potential Mechanisms for a Link Between Work Stress and CHD

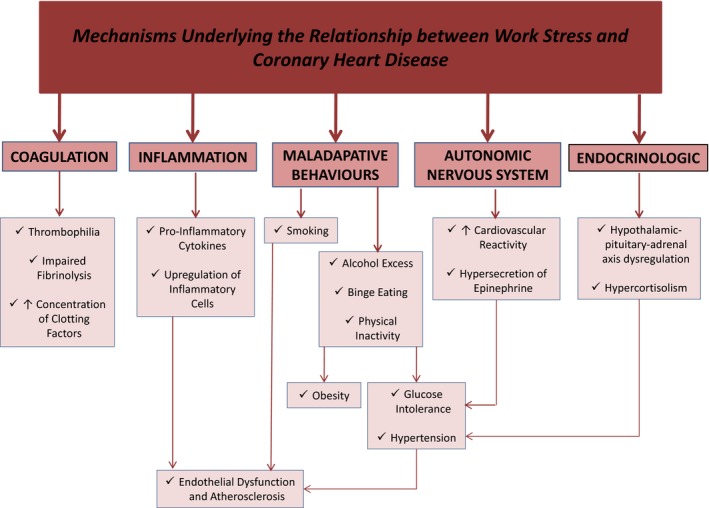

There are several mechanisms by which it is plausible that work stress can contribute to the development of CHD (Figure 3). Biological pathways implicated in the development of CHD may be influenced by psychosocial factors. Under normal physiological conditions, cortisol secretion is increased in response to psychological stress and elevated levels have been documented in states of depression and hostility as well as work stress.20, 88, 89 Although cortisol normally reduces inflammation, oversecretion may result in resistance to its anti‐inflammatory properties, rendering the body vulnerable to inflammatory disorders, such as atherosclerosis.80, 81 For example, high job demand has been associated with more rapid progression of carotid atherosclerosis.90 Excessive cortisol may also result in dysregulation to the negative feedback system of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis, further perpetuating elevations in cortisol. Increased inflammatory markers, such as C‐reactive protein and interleukin‐6, have prospectively predicted coronary events in healthy asymptomatic populations, and elevated levels of C‐reactive protein and other proinflammatory cytokines have been noted in individuals with depression.91 This, however, has not been demonstrated in subjects with high work stress. It may be that elevated inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor‐α, noted in depression, are responsible for this condition's physical symptoms of anorexia and sleep disturbance in the same way as for malignant diseases but may not have a direct role in linking psychosocial stressors to CHD.

Figure 3.

Potential mechanisms by which work‐related stress may lead to coronary heart disease.

Work stress has also been associated with increased levels of epinephrine and long‐term sympathetic activation,20 which may have a role in activating platelets and macrophages, upregulating the expression of inflammatory cytokines,92 and, as with cortisol, contributing to the development of high blood pressure, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia, all components of the metabolic syndrome. In fact, work stress has been shown to be an independent risk factor for hypertension,93, 94 and job strain, in particular, results in higher ambulatory blood pressure levels in a dose‐response relationship, even beyond working hours.94 Although hypertension is a conventional cardiovascular risk factor associated with increased rates of CHD, cardiovascular reactivity is a novel risk factor that may promote atherogenesis and lead to CVD events. In one study, greater cardiovascular reactivity was demonstrated in subjects with work stress.95 Similarly, low socioeconomic status and mental stress have both been linked to pathological lipid profiles.96, 97 Although one study suggested that work stress does not influence serum lipid or glucose levels,98 several other studies have shown a link between components of the metabolic syndrome and work stress. For example, in one French cross‐sectional study consisting of 43 593 men and women, work stress, characterized by the effort‐reward imbalance model, was associated with significantly lower levels of high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol among men and a higher BMI in both men and women, even after adjusting for covariables, such as age, socioeconomic status, health‐related behaviors, and symptoms of depression.99 In another study from Germany, work stress, also characterized by the effort‐reward imbalance model, was associated with the metabolic syndrome, which was defined as the presence of at least 3 of the following 5 components: increased blood pressure, elevated triglycerides, low high‐density lipoprotein, increased fasting glucose, and central obesity. This relationship was strongest among younger men.100 In another study among Korean blue collar workers, who worked in jobs such as shipbuilding and manufacturing industry, effort‐reward imbalance was associated with metabolic syndrome, characterized as the presence of all 5 components of the syndrome, in both men and women.101 Although these studies are limited by their cross‐sectional design, several prospective studies have shown similar findings. In one study that followed up 290 police officers over a 5‐year period, work stress, characterized as job strain or effort‐reward imbalance, was associated with metabolic syndrome as well as hypertriglyceridemia, even after adjusting for numerous sociodemographic variables (namely, age, rank, education, geographic origin, marital status, housing, presence of offspring, smoking, and sleep habits). The authors also found that job demand and work effort were independent predictors of metabolic syndrome.102 In a further prospective study that included an unselected population‐based cohort, job strain as well as low‐decision latitude in isolation were significantly associated with new‐onset type 2 diabetes mellitus among women. Interestingly, high job strain and high work demand in isolation decreased the risk of new‐onset type 2 diabetes mellitus among men. Further studies will be required to better understand the relationship between work stress and the various components of metabolic syndrome as well as the potential effect modification of sex.

The stress associated with increased workload is associated with increased platelet count and aggregation as well as elevated levels of factors VII and VIII,103 resulting in a prothrombotic state. In addition, work stress has been shown to lead to impaired fibrinolysis through decreased levels of tissue plasminogen activator and increased levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor antigen.104 The relationship between work stress and fibrinogen levels, however, remains more uncertain. Although several large studies have found that increased levels of work stress are associated with elevated fibrinogen levels,105, 106, 107 other studies have failed to show any association.104, 108 One study, in particular, demonstrated that in the setting of mental stress, subjects with low job control had an exaggerated fibrinogen response compared with those with high job control.109 Elevated fibrinogen levels are a powerful predictor for myocardial infarction110, 111 and are associated with several cardiovascular risk factors,112, 113, 114 thus providing a potential mechanistic explanation for an increased risk of coronary events among those experiencing increased work stress. Increased job strain among both men and women was associated with elevated levels of fibrinogen, which, in turn, were associated with increased age, BMI, and total cholesterol as well as the presence of hypertension, smoking, and diabetes mellitus.115

Endothelial dysfunction is characterized by reduced coronary blood flow secondary to impaired vasoreactivity of the coronary microcirculation and/or epicardial vessels. It can precede atherosclerosis and may independently lead to adverse CVD events.83 Short‐term episodes of mental stress have been shown to cause reversible endothelial dysfunction in healthy individuals.85 Although depression has been associated with endothelial dysfunction,116 the precise role work stress plays on endothelial function remains uncertain. Given its central role to several potential mechanisms related to both work stress and CHD, including inflammation, and modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (Figure 3), endothelial dysfunction may play a pivotal role in the link between work stress and cardiovascular health and could potentially offer an integrated index of risk. However this remains an understudied area and requires further investigation. The relationship between other novel risk factors for CVD and work stress has also been sparsely studied, an example of which is carotid intima‐media thickness, which, like endothelial dysfunction, is a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis and is associated with an increased risk of CVD events.117 In one prospective study following up 3109 workers over a period of 9.4 years, physical activity on the job, interpersonal stress, job control, and job demands were not significantly associated with carotid intima‐media thickness at baseline or with its progression over time. Among men, the only significant predictor of increased carotid intima‐media thickness over time was occupational position, such that those in roles such as farming, fishing, construction, extraction, and transportation had more significant disease progression compared with those in professional roles. Among women, the only predictor of carotid intima‐media thickness progression was physical hazards on the job.118 Further study of this and other novel risk factors for CVD would be useful. The aforementioned description of potential biological mechanisms that may underlie the relationship between work stress and CHD represents a simplified view that does not factor in the potential roles of other occupational and social factors that could contribute to work stress and its effect on CHD. Further studies are required to clarify the role of these and additional psychosocial and environmental factors in mediating the relationship between work stress and CHD and adverse health in general and to determine what pathophysiological consequences they may have.

In addition to intrinsic markers becoming deranged with increased work stress, the work environment can contribute to the adoption of high‐risk behaviors among individuals, further increasing the risk of CHD. Increased job strain has been linked to unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking, physical inactivity, and poor diet,119 an association that has also been noted with other psychosocial stressors, like social isolation, and conditions, such as depression. Moreover, workplaces that focus on healthy living and the overall physical and mental wellbeing of their employees are more likely to provide a favorable work environment, with decreased job strain, in part through the promotion of physical exercise and making use of gyms and “wellness centers.”120

Management of Work Stress

Because work‐related stress may contribute to an increased incidence of CHD, it is important to explore possible interventions that may help alleviate work‐related stress. van der Klink and colleagues studied the effectiveness of occupational stress‐reducing interventions in a meta‐analysis that included 48 studies (n=3736) and reported that individual‐directed interventions were more effective than occupational‐based interventions and that, of these, cognitive‐behavioral therapy based interventions were most effective (Cohen's d, 0.68; P<0.05).121 Previous studies have also supported this finding.122 Cognitive‐behavioral therapy had the most positive effect on outcomes, such as psychologic responses and resources to stress and complaints of anxiety‐related symptoms and had the added benefit of having an inverse relationship between effect size and number of required sessions. Relaxation therapy was the next most effective intervention (Cohen's d, 0.35; P<0.05) and was the best intervention for modifying psychophysiologic outcomes. The authors also concluded that stress‐related interventions worked best in employees who have greatest job control at baseline. Conversely, in another systematic review, Lamontagne et al evaluated 90 studies assessing work‐stress interventions between 1990 and 2005 and concluded that the best interventions were those that included both individual and organizational focused interventions, and where only one was present, organizational interventions were more important.123 This may be because the effects of a single intervention affect more people but does not take into consideration the cost and time that may be required to implement an occupational‐based intervention. Although occupational‐based interventions tend to enhance an employee's level of job control, individualized interventions improve perceptions and coping skills.124 The most effective interventions, therefore, seem to be individualized cognitive‐behavior therapy–based interventions in subjects with preexisting high levels of job control, which may be achieved by influencing perception of work environment and enhancing psychological resources. For those with low job control, occupational interventions that provide greater variety in daily tasks with increased decision‐making capacity may enhance job control. This can be demonstrated using social cognitive theory, which highlights the importance of improved self‐efficacy, positive reenforcement of newly developed constructive behaviors, higher levels of self‐determinism, and ultimately reciprocal determinism through positive influence on the behavior of oneself, one's colleagues, and one's environment.125 Workers with enhanced control may then benefit more from cognitive‐based therapy interventions, where appropriate. Where neither method works, passive strategies to enhance coping and address symptoms with relaxation therapy may be suitable, which could be available to employees in their workplace. How organizations actually enact some of these changes is challenging. One systematic review by Narvaez et al outlined the importance and effectiveness of using measures supported by information technology to help prevent and treat work‐related stress.126 However, these interventions have been infrequently used to date, and what exactly is the role of information technology in the management of work stress remains unclear.

A meta‐analysis looking at 20 randomized controlled trials evaluating the utility of several psychosocial treatment strategies, including relaxation training, cognitive‐behavioral therapy, meditation, group emotional support, and the provision of home nursing interventions, to reduce stress found that patients receiving psychosocial treatments showed greater reductions compared with controls in psychological distress, blood pressure, heart rate, and serum cholesterol. Half of the included studies evaluated the impact on morbidity and mortality and found that patients not receiving psychosocial treatments had higher mortality and adverse cardiac event rates compared with those receiving these treatments.127 Thus, these interventions were able to positively influence both biological and psychosocial symptoms and, in doing so, yielded improvements to patient outcomes. Subsequent meta‐analyses demonstrated mixed results, with 1 demonstrating a positive effect of psychosocial treatments on cardiac morbidity,128 2 demonstrating no effect of these treatments on cardiac morbidity,129, 130 and a final review, which evaluated 14 psychosocial intervention trials, demonstrating a mixture of positive and equivocal influences of psychological treatments on cardiac morbidity.20 These studies further implicate a psychosocial component contributing to the cause of CHD and suggest that symptoms related to stress may form important targets for psychosocial interventions. In addition, although many studies fail to show an improvement in cardiac events, some have shown improvements in more modest, but nevertheless relevant, end points. One study, for example, found psychosocial intervention programs to improve markers of CVD risk, such as endothelial dysfunction.131 Further interventional trials evaluating larger sample sizes are necessary to elucidate which treatments are most effective and which individual characteristics respond best to them. Although contemporary primary and secondary preventative pharmacotherapy and behavioral modifications have been implemented and yield results on the population level, psychosocial interventions may require a greater degree of individualization, depending on patient demographics, psychosocial characteristics, and symptoms.

The vast majority of the interventions to improve work stress that have been trialed in the workplace and studied have focused on individual‐based measures. This overemphasis of individual‐based interventions, as opposed to wider modifications to the work environment, does not necessarily mean that individual‐based interventions are more effective, but may reflect the fact that these interventions are easier to implement and study. Workplace‐based interventions are inevitably more costly, take more time to implement, and require the relevant workplace management to commit to the workplace‐based changes. This in itself introduces further potential bias because management willing to modify workplace environments to help improve work stress may belong to a group of managers who acknowledge the importance of workers’ wellness and have already implemented other workplace measures to help mitigate workplace‐related stress. Management willing to make significant changes to a work environment to combat stress may also have spent time previously in cultivating a workplace culture of lower levels of stress and greater emphasis on employee wellness. These systematic differences between managers willing to implement workplace environment changes to help alleviate stress and those unwilling or unable to implement changes make it difficult to determine if modifying the workplace environment per se is responsible for improvements in work stress and, in turn, CHD and adverse health or if the preexisting factors were more relevant. Investigating modifications to the workplace environment on their own as part of a randomized controlled trial would be a costly and time‐consuming undertaking and, as yet, studies of this nature are sparse. Furthermore, although individual‐based therapies are easier to implement, are simpler to evaluate as part of a controlled study, and are likely to be less costly, the effectiveness of individual‐based therapy in one individual or group does not necessarily translate into effectiveness in all individuals or groups. Individuals are different and bring with them a unique mixture of psychosocial attributes, personality traits, and physiological characteristics, and what may be helpful to one person or group may be ineffective among others.

Few studies have also evaluated whether influencing work stress, whether through individual‐ or work environment–based interventions, directly reduces the incidence of CHD. Thus, given the limited evidence on benefits, harms, and cost‐effectiveness of such interventions, no definitive recommendations have emerged from organizations such as the US Preventative Services Task Force for the primary prevention of CHD by means of work stress reduction. Nevertheless, some governments have already introduced workplace‐related campaigns to limit work stress and, in some countries, a commitment to reducing work stress has become a legal requirement. For example, the European Union's Working Time Directive132 mandates that corporations based in member states comply with certain tightly regulated working patterns that the directive stipulates should be adhered to in order to help mitigate work stress and its potentially related adverse health consequences. Among industrialized nations with democratic political processes, social pressures calling for increased workplace oversight and regulation mean that such interventions are likely to become increasingly common.

Conclusion

There are growing amounts of evidence supporting a role for job strain, effort‐reward imbalance, and organizational injustice contributing to CHD. This is further supported by evidence that links work stress to traditional CVD risk factors and established pathological mechanisms. However, whether work stress actually causes CHD still remains uncertain, largely because of questions about the validity of study design in addition to the significant number of studies that fail to demonstrate a positive link between work stress and CHD. Work stress is likely to remain a significant facet of the 21st century lifestyle and, with this, further work is required to determine its precise role in the pathological features of CHD and which interventions can be best used to modify it.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed significantly to this article and have read and approved of the final version.

J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008073 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008073.29703810

References

- 1. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manojlovic N, Babic D, Stojanovic S, Filipovic I, Radoje D. Capecitabine cardiotoxicity: case reports and literature review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1249–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, Finkelstein EA, Hong Y, Johnston SC, Khera A, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Nelson SA, Nichol G, Orenstein D, Wilson PW, Woo YJ. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case‐control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weintraub WS, Daniels SR, Burke LE, Franklin BA, Goff DC Jr, Hayman LL, Lloyd‐Jones D, Pandey DK, Sanchez EJ, Schram AP, Whitsel LP. Value of primordial and primary prevention for cardiovascular disease: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:967–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. British Cardiac Society, British Hypertension Society, Diabetes UK, HEART UK, Primary Care Cardiovascular Society, The Stroke Association . JBS 2: “Joint British Societies” guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart. 2005;91(suppl 5):1–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PW, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1991;121:293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, Sans S, Menotti A, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Ducimetiere P, Jousilahti P, Keil U, Njolstad I, Oganov RG, Thomsen T, Tunstall‐Pedoe H, Tverdal A, Wedel H, Whincup P, Wilhelmsen L, Graham IM. Estimation of ten‐year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the score project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jackson R. Updated New Zealand cardiovascular disease risk‐benefit prediction guide. BMJ. 2000;320:709–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lloyd‐Jones DM. Cardiovascular risk prediction: basic concepts, current status, and future directions. Circulation. 2010;121:1768–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD; American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Force and Statistics Committee . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beaglehole R, Magnus P. The search for new risk factors for coronary heart disease: occupational therapy for epidemiologists? Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1117–1122; author reply 1134–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee MS, Flammer AJ, Li J, Lennon RJ, Singh M, Holmes DR Jr, Rihal CS, Lerman A. Time‐trend analysis on the Framingham risk score and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention without prior history of coronary vascular disease over the last 17 years: a study from the Mayo Clinic PCI registry. Clin Cardiol. 2014;37:408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurt RD, Weston SA, Ebbert JO, McNallan SM, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR, Roger VL. Myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death in Olmsted County, Minnesota, before and after smoke‐free workplace laws. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1635–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khawaja FJ, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, Holmes DR, Prasad A. Temporal trends (over 30 years), clinical characteristics, outcomes, and gender in patients </=50 years of age having percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akosah KO, Schaper A, Cogbill C, Schoenfeld P. Preventing myocardial infarction in the young adult in the first place: how do the national cholesterol education panel III guidelines perform? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1475–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Mockenhaupt RE. Broadening the focus: the need to address the social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:S4–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Albus C. Psychological and social factors in coronary heart disease. Ann Med. 2010;42:487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999;99:2192–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Twisk JW, Snel J, de Vente W, Kemper HC, van Mechelen W. Positive and negative life events: the relationship with coronary heart disease risk factors in young adults. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, Hickie IB, Hunt D, Jelinek VM, Oldenburg BF, Peach HG, Ruth D, Tennant CC, Tonkin AM. “Stress” and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors. Med J Aust. 2003;178:272–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krantz DS, McCeney MK. Effects of psychological and social factors on organic disease: a critical assessment of research on coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:341–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strike PC, Steptoe A. Psychosocial factors in the development of coronary artery disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;46:337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peter R, Siegrist J. Psychosocial work environment and the risk of coronary heart disease. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;73(suppl):S41–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bejean S, Sultan‐Taieb H. Modeling the economic burden of diseases imputable to stress at work. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karasek R, Baker D, Marxer F, Ahlbom A, Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:694–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karasek RA, Theorell T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schnall PL, Landsbergis PA, Baker D. Job strain and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:381–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marmot M, Theorell T. Social class and cardiovascular disease: the contribution of work. Int J Health Serv. 1988;18:659–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kivimaki M, Leino‐Arjas P, Luukkonen R, Riihimaki H, Vahtera J, Kirjonen J. Work stress and risk of cardiovascular mortality: prospective cohort study of industrial employees. BMJ. 2002;325:857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bosma H, Marmot MG, Hemingway H, Nicholson AC, Brunner E, Stansfeld SA. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in Whitehall II (prospective cohort) study. BMJ. 1997;314:558–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kasl SV. The influence of the work environment on cardiovascular health: a historical, conceptual, and methodological perspective. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1:42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van der Doef M, Maes S. The job demand‐control (‐support) model and psychological well‐being: a review of 20 years of empirical research. Work Stress. 1999;13:87–114. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kristensen TS. The demand‐control‐support model: methodological challenges for future research. Stress Health. 1995;11:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross‐sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1336–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pelfrene E, Vlerick P, Kittel F, Mak R, Kornitzer M, de Backer G. Psychological work environment and psycho‐logical well‐being: assessment of the buffering effects in the job demand–control (–support) model in BELSTRESS. Stress Health. 2002;18:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high‐effort/low‐reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1:27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Siegrist J, Peter R, Junge A, Cremer P, Seidel D. Low status control, high effort at work and ischemic heart disease: prospective evidence from blue‐collar men. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:1127–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alterman T, Shekelle RB, Vernon SW, Burau KD. Decision latitude, psychologic demand, job strain, and coronary heart disease in the Western Electric Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Vegchel N, de Jonge J, Bosma H, Schaufeli W. Reviewing the effort‐reward imbalance model: drawing up the balance of 45 empirical studies. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1117–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brockner J, Wiesenfeld BM. An integrative framework for explaining reactions to decisions: interactive effects of outcomes and procedures. Psychol Bull. 1996;120:189–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fehr E, Fischbacher U. The nature of human altruism. Nature. 2003;425:785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Miller DT. Disrespect and the experience of injustice. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:527–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Szerencsi K, van Amelsvoort L, Prins M, Kant I. The prospective relationship between work stressors and cardiovascular disease, using a comprehensive work stressor measure for exposure assessment. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2014;87:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Singh‐Manoux A, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, Bjorner JB, Borritz M, Burr H, Casini A, Clays E, De Bacquer D, Dragano N, Erbel R, Geuskens GA, Hamer M, Hooftman WE, Houtman IL, Jockel KH, Kittel F, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Lunau T, Madsen IE, Nielsen ML, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pejtersen JH, Pentti J, Rugulies R, Salo P, Shipley MJ, Siegrist J, Steptoe A, Suominen SB, Theorell T, Vahtera J, Westerholm PJ, Westerlund H, O'Reilly D, Kumari M, Batty GD, Ferrie JE, Virtanen M; IPD‐Work Consortium . Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet. 2015;386:1739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Netterstrom B, Kristensen TS. Psychosocial factors at work and ischemic heart disease [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2005;167:4348–4355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eller NH, Netterstrom B, Gyntelberg F, Kristensen TS, Nielsen F, Steptoe A, Theorell T. Work‐related psychosocial factors and the development of ischemic heart disease: a systematic review. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kivimaki M, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Kouvonen A, Vaananen A, Vahtera J. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease: a meta‐analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nyberg ST, Fransson EI, Heikkila K, Alfredsson L, Casini A, Clays E, De Bacquer D, Dragano N, Erbel R, Ferrie JE, Hamer M, Jockel KH, Kittel F, Knutsson A, Ladwig KH, Lunau T, Marmot MG, Nordin M, Rugulies R, Siegrist J, Steptoe A, Westerholm PJ, Westerlund H, Theorell T, Brunner EJ, Singh‐Manoux A, Batty GD, Kivimaki M. Job strain and cardiovascular disease risk factors: meta‐analysis of individual‐participant data from 47,000 men and women. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Backe EM, Seidler A, Latza U, Rossnagel K, Schumann B. The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85:67–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Belkic KL, Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Baker D. Is job strain a major source of cardiovascular disease risk? Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004;30:85–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Burr H, Formazin M, Pohrt A. Methodological and conceptual issues regarding occupational psychosocial coronary heart disease epidemiology. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Szerencsi K, van Amelsvoort LG, Viechtbauer W, Mohren DC, Prins MH, Kant I. The association between study characteristics and outcome in the relation between job stress and cardiovascular disease: a multilevel meta‐regression analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012;38:489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Aboa‐Eboule C, Brisson C, Maunsell E, Masse B, Bourbonnais R, Vezina M, Milot A, Theroux P, Dagenais GR. Job strain and risk of acute recurrent coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2007;298:1652–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bosma H, Peter R, Siegrist J, Marmot M. Two alternative job stress models and the risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. De Bacquer D, Pelfrene E, Clays E, Mak R, Moreau M, de Smet P, Kornitzer M, De Backer G. Perceived job stress and incidence of coronary events: 3‐year follow‐up of the Belgian Job Stress Project cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Eaker ED, Sullivan LM, Kelly‐Hayes M, D'Agostino RB Sr, Benjamin EJ. Does job strain increase the risk for coronary heart disease or death in men and women? The Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Johnson JV, Hall EM, Theorell T. Combined effects of job strain and social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in a random sample of the Swedish male working population. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1989;15:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kornitzer M, deSmet P, Sans S, Dramaix M, Boulenguez C, DeBacker G, Ferrario M, Houtman I, Isacsson SO, Ostergren PO, Peres I, Pelfrene E, Romon M, Rosengren A, Cesana G, Wilhelmsen L. Job stress and major coronary events: results from the Job Stress, Absenteeism and Coronary Heart Disease in Europe study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kuper H, Singh‐Manoux A, Siegrist J, Marmot M. When reciprocity fails: effort‐reward imbalance in relation to coronary heart disease and health functioning within the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:777–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Laszlo KD, Ahnve S, Hallqvist J, Ahlbom A, Janszky I. Job strain predicts recurrent events after a first acute myocardial infarction: The Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. J Intern Med. 2010;267:599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee S, Colditz G, Berkman L, Kawachi I. A prospective study of job strain and coronary heart disease in US women. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1147–1153; discussion 1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Netterstrom B, Kristensen TS, Sjol A. Psychological job demands increase the risk of ischaemic heart disease: a 14‐year cohort study of employed Danish men. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Reed DM, LaCroix AZ, Karasek RA, Miller D, MacLean CA. Occupational strain and the incidence of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Slopen N, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, Lewis TT, Williams DR, Albert MA. Job strain, job insecurity, and incident cardiovascular disease in the Women's Health Study: results from a 10‐year prospective study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Steenland K, Johnson J, Nowlin S. A follow‐up study of job strain and heart disease among males in the NHANES1 population. Am J Ind Med. 1997;31:256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Uchiyama S, Kurasawa T, Sekizawa T, Nakatsuka H. Job strain and risk of cardiovascular events in treated hypertensive Japanese workers: hypertension follow‐up group study. J Occup Health. 2005;47:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kuper H, Adami HO, Theorell T, Weiderpass E. Psychosocial determinants of coronary heart disease in middle‐aged women: a prospective study in Sweden. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Andre‐Petersson L, Engstrom G, Hedblad B, Janzon L, Rosvall M. Social support at work and the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in women and men. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:830–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kivimaki M, Theorell T, Westerlund H, Vahtera J, Alfredsson L. Job strain and ischaemic disease: does the inclusion of older employees in the cohort dilute the association? The WOLF Stockholm Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:372–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Elovainio M, Leino‐Arjas P, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M. Justice at work and cardiovascular mortality: a prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tsutsumi A, Kayaba K, Hirokawa K, Ishikawa S; Jichi Medical School Cohort Study Group . Psychosocial job characteristics and risk of mortality in a Japanese community‐based working population: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1276–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kivimaki M, Ferrie JE, Brunner E, Head J, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Marmot MG. Justice at work and reduced risk of coronary heart disease among employees: the Whitehall II study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2245–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rose G, McCartney P, Reid DD. Self‐administration of a questionnaire on chest pain and intermittent claudication. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977;31:42–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hallqvist J, Diderichsen F, Theorell T, Reuterwall C, Ahlbom A. Is the effect of job strain on myocardial infarction risk due to interaction between high psychological demands and low decision latitude? Results from Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP). Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1405–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Marmot MG, Shipley MJ, Rose G. Inequalities in death: specific explanations of a general pattern? Lancet. 1984;1:1003–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Marmot MG, Bosma H, Hemingway H, Brunner E, Stansfeld S. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet. 1997;350:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. Do cardiovascular risk factors explain the relation between socioeconomic status, risk of all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and acute myocardial infarction? Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:934–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lind L. Circulating markers of inflammation and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2003;169:203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ross R. Atherosclerosis: an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Avogaro A, de Kreutzenberg SV. Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in obesity. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;360:9–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bonetti PO, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Endothelial dysfunction: a marker of atherosclerotic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:III27–III32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ghiadoni L, Donald AE, Cropley M, Mullen MJ, Oakley G, Taylor M, O'Connor G, Betteridge J, Klein N, Steptoe A, Deanfield JE. Mental stress induces transient endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation. 2000;102:2473–2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Orth‐Gomer K, Wamala SP, Horsten M, Schenck‐Gustafsson K, Schneiderman N, Mittleman MA. Marital stress worsens prognosis in women with coronary heart disease: the Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study. JAMA. 2000;284:3008–3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. de Smet P, Sans S, Dramaix M, Boulenguez C, de Backer G, Ferrario M, Cesana G, Houtman I, Isacsson SO, Kittel F, Ostergren PO, Peres I, Pelfrene E, Romon M, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L, Kornitzer M. Gender and regional differences in perceived job stress across Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Theorell T, Emdad R, Arnetz B, Weingarten AM. Employee effects of an educational program for managers at an insurance company. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:724–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]