Abstract

IFNL4 is linked to hepatitis C virus treatment response and type III interferons (IFNs). We studied the functional associations among hepatic expressions of IFNs and IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), and treatment response to peginterferon and ribavirin. Type I IFNs (IFNA1, IFNB1), type II (IFNG), type III (IFNL1, IFNL2/3), IFNL4 and ISG hepatic expressions were measured by qPCR from in 65 chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients whose IFNL4-associated rs368234815 and IFNL3-associated rs12989760 genotype were determined. There was a robust correlation of hepatic expression within type I and type III IFNs and between type III IFNs and IFNL4 but no correlation between other IFN types. Expression of ISGs correlated with type III IFNs and IFNL4 but not with type I IFNs. Levels of ISGs and IFNL2/3 mRNAs were lower in IFNL3 rs12979860 CC patients compared with non-CC patients, and in treatment responders, compared with nonresponders. IFNL4-ΔG genotype was associated with high ISG levels and nonresponse. Hepatic levels of ISGs in CHC are associated with IFNL2/3 and IFNL4 expression, suggesting that IFNLs, not other types of IFNs, drive ISG expression. Hepatic IFNL2/3 expression is functionally linked to IFNL4 and IFNL3 polymorphisms, potentially explaining the tight association among ISG expression and treatment response.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is the a major cause of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and end-stage liver disease in the United States.1 Previous treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infection includes combination of peginterferon (Peg-IFN) and ribavirin, which achieves a sustained virologic response of less than 55%.2 The development of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for the treatment of HCV infection has promised highly effective treatment with shorter duration.3 Newer DAAs have either been approved or are in the pipeline with interferon (IFN)-free regimens.4 Recently, endogenous IFN response was found to play a role in DAA (sofosbuvir)-mediated viral clearance, potentially explaining relapse in DAA IFN-free regimens.5,6 There is increasing evidence that type III IFNs play a major role in hepatic antiviral response.7

IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) were previously found to predict IFN-based treatment response.8,9 High levels of hepatic expression of ISGs prior to treatment are associated with treatment unresponsiveness, whereas low levels are associated with a favorable treatment response.8,9 ISG mRNA levels were recently shown to decrease in the liver during sofosbuvir treatment, suggesting their ongoing role in DAA-mediated HCV viral clearance.5 A highly significant association of IFN-based treatment response has been established with rs12979860, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) near the IFNL3 (previously known as IL28B) gene on chromosome 2, encoding IFN-λ3/interleukin-28B, a type III IFN.10–12 This and other SNPs in the region were subsequently shown to be associated with natural clearance of HCV.13,14 However, the aforementioned SNPs are not in a coding region and therefore, the mechanism underlying their association with treatment response is unclear. A more recently discovered dinucleotide polymorphism rs368234815 (combining the SNPs rs11322783 and rs74597329) (TT or ΔG) was found to be in high linkage disequilibrium with rs12979860.15 One of the rs368234815 alleles (ΔG) results in a frame-shift variation leading to transcription and translation of a novel gene product, named IFN-λ4 (IFNL4), which shares 41% amino acids sequence similarity with IFNL3, and is capable of inducing the expression of ISGs.15 The IFNL4 ΔG genotype correlates with slow viral decline and low sustained virologic response in patients treated with Peg-IFN and ribavirin better than rs12979860.15,16 However, the functional linkage of the IFNL3 variations and IFNL4 to treatment response is not completely understood. More recently, another study identified a functional polymorphism (rs4803217) located in the 3′ untranslated region of the IFNL3 mRNA that dictates transcript stability. This polymorphism affects AU-rich element-mediated decay and the binding of HCV-induced microRNAs during infection. The unfavorable IFNL3 genotype was repressed by this pathway, potentially providing an alternative functional explanation.17

Interestingly, IFNL4 genotypes were also recently found to be associated with viral clearance during IFN-free treatment that includes sofosbuvir treatment.6 Patients with the IFNL4 ΔG genotype were found to have a slower rate of response compared with patients with the TT genotype. These data suggested a functional role of IFNL4 in IFN-free DAA regimens. This is of particular importance as the new DAA treatments are very expensive with variable durations ranging from 8 to 24 weeks. Therefore, studies investigating the role of IFNL4 and other IFNs may help to identify those who can respond faster to DAAs and require shorter duration of treatment.

Type III IFNs (IFNL1 (previously IL29), IFNL2 (previously IL28A) and IFNL3 (previously IL28B)) are able to induce ISGs similar to type I IFNs (α and β)18 and were recently shown to be the predominant IFNs induced in vitro in HCV-infected primary human hepatocytes and in the liver of chimpanzees.7,19 Another study showed a correlation between hepatic IFNL3 and ISG mRNA levels in CHC patients, but there was no significant correlation between hepatic IFNL3 expression and the IFNL3 SNP rs8099917.20 The lack of correlation between hepatic IFNL3 levels and the IFNL3 SNPs was attributed by the authors to possible methodological issues, which include low levels of hepatic expression of IFNL3 and the lack of specificity of qPCR primers to distinguish between IFNL2 and IFNL3. One recent study demonstrated high hepatic ISG levels but low IFNL3 level in association with IFNL3 rs12979860 TT genotype (treatment unfavorable).21 In contrast, several other studies showed an association between low hepatic IFNL3 levels and IFNL3 treatment-favorable genotype,22–24 or no relationship between IFNL3 levels and IFNL3 genotypes.25 Therefore, expression of type III IFNs, particularly IFNL2/3, and ISGs in correlation with IFNL3 polymorphisms and treatment response remains unresolved. In addition, the interaction between other types of IFNs including type I and II IFNs and their relationship with type III IFNs, the newly discovered IFNL4, and treatment response have not been thoroughly explored. In this study, we investigate extensively the associations among hepatic expression of IFNs (type I, II, III) and ISGs, the IFNL3 polymorphisms (IL28B) and response to Peg-IFN/RBV treatment in a large cohort of CHC patients.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Sixty-five CHC patients were enrolled and their characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and viral load were 75.0 ± 47.0 U l −1, 72.3 ± 61.3 U l −1 and 6.2 ± 0.9 log10 IU ml −1, respectively. The distribution of HCV genotype was: genotype 1 (82%), genotype 2 and 3 (15%) and other genotypes (4–6) (3%). The distribution of IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype was CC (45%), CT (39%) and TT (16%) and that of IFNL4 rs368234815 genotype was TT/TT (52%), TT/ΔG (30%) and ΔG/ΔG (18%). As expected, the linkage disequilibrium between the two SNPs is high with 93% concordance (r2 = 0.83).

Table 1.

Baseline patients’ characteristics

| Characteristics | All patients (65) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Male, n (%) | 37 (57%) |

| Age (mean, s.d.), years | 50.7 (7.5) |

| White, n (%) | 45 (69%) |

| Asian, n (%) | 10 (16%) |

| Hispanic (%) | 2 (3%) |

| African American, n (%) | 8 (12%) |

| Viral genotype | |

| Genotype 1, n (%) | 53 (82%) |

| Genotype 2 and 3, n (%) | 10 (15%) |

| Genotypes 4–6, n (%) | 2 (3%) |

| IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype | |

| CC (%) | 29 (45%) |

| CT (%) | 25 (39%) |

| TT (%) | 11 (16%) |

| IFNL4 rs368234815 genotype | |

| TT/TT (%) | (32/62) (52%) |

| TT/ΔG (%) | (19/62) (30%) |

| ΔG/ΔG (%) | (11/62) (18%) |

| Laboratory data | |

| ALT (mean, s.d.) (U l−1) | 75.0 (47.0) |

| AST (mean, s.d.) (U l−1) | 72.3 (61.3) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (mean, s.d.) (U l−1) | 73.5 (28.0) |

| Albumin (mean, s.d.) (g dl−1) | 3.9 (0.5) |

| Bilirubin, total (mean, s.d.) (mg dl−1) | 0.8 (0.3) |

| Bilirubin, direct (mean, s.d.) (mg dl−1) | 0.2 (0.1) |

| International normalized ratio (mean, s.d.) | 1.0 (0.1) |

| HCV viral load log10 ml−1 (mean, s.d.) | 6.2 (0.9) |

| Histological data | |

| HAI score | 7.8 (2.8) |

| Ishak fibrosis score | 2.3 (1.6) |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HAI, histological activity index; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Baseline hepatic expression of IFNs and ISGs

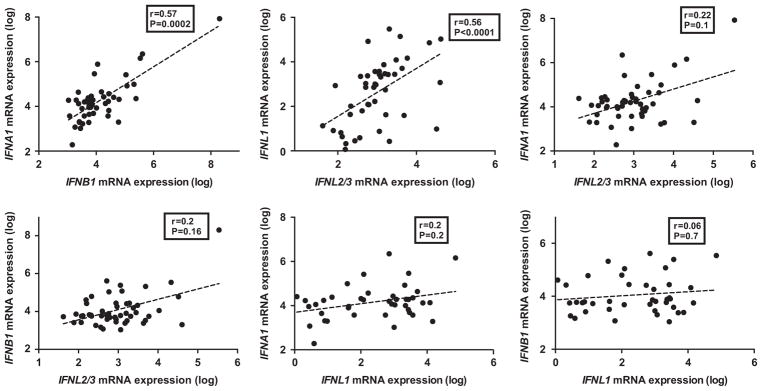

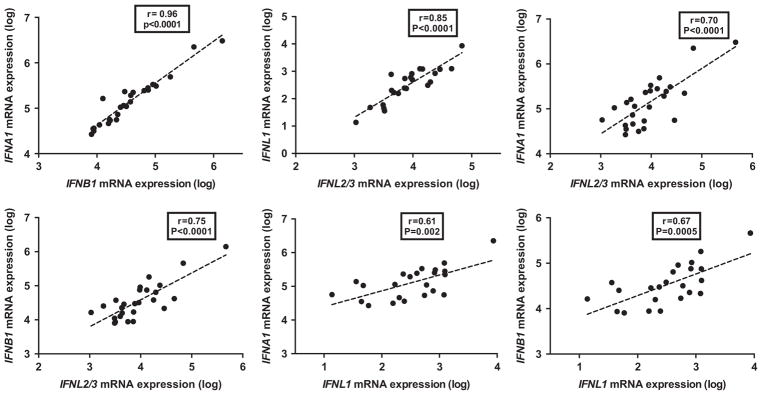

We first measured the hepatic expression of type I (IFNA1 and IFNB1), type II (IFNG) and type III IFNs (IFNL2/3 and IFNL1) prior to any IFN-based therapy. There was a robust correlation between IFNA1 and IFNB1, the two type I IFNs (r = 0.57; P = 0.0002). Similarly, there was a robust correlation between the IFNL2/3 and IFNL1 (r = 0.56; P<0.0001) (Figure 1). There was no significant correlation between type III and type I IFNs (Figure 1). IFNG, the type II IFN, did not correlate with other IFNs except for a weak correlation with IFNL1 (r = 0.3; P = 0.04) (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Pair-wise correlations between hepatic expression levels of IFNs. Hepatic expression (log-transformed arbitrary units) of IFNA1, IFNB1, IFNL2/3 and IFNL1 by qPCR prior to Peg-IFN injection in 65 samples and pairwise correlations (Spearman’s r). P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

To determine which IFN is associated with ISG expression, we determined the hepatic expression of several ISGs using qPCR including ISG15, IFI44, IFIT1, OAS3 and RSAD2.

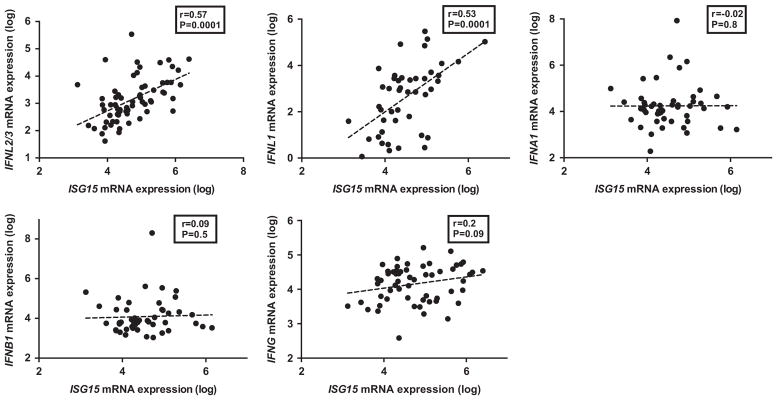

ISG15 expression was correlated with both type III IFNs (IFNL2/3, r = 0.57, P = 0.0001; and IFNL1, r = 0.53; P = 0.0001) (Figure 2). ISG15 was weakly correlated with IFNG but did not reach statistical significance (r = 0.20; P = 0.09); however, it did not correlate with IFNA1 or IFNB1. Similarly, other ISGs correlated significantly with IFNL2/3, IFNL1 and to a lesser extent with IFNG, but not with the type I IFNs (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Correlation of hepatic expression between ISGs and IFNs. Hepatic expression (log-transformed arbitrary units) of IFNA1, IFNB1, IFNL2/3, IFNL1 and IFNG by qPCR in 65 samples and its correlation (Spearman’s r) with ISG15 expression. P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

Table 2.

Correlation between log-transformed hepatic expression of ISGs and IFNs (by qPCR) in liver samples from patients with chronic hepatitis C

| ISG | IFNA1 (n = 48a)

|

IFNB1 (n = 48)

|

IFNG (n = 48)

|

IFNL2/3 (n = 48)

|

IFNL1 (n = 48)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P-value | r | P-value | r | P-value | r | P-value | r | P-value | |

| IFI44 (n =42) | −0.05 | 0.78 | −0.02 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.01 |

| IFIT1 (n =64) | −0.22 | 0.14 | −0.22 | 0.12 | 0.51a | <0.0001 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.45 | <0.0001 |

| ISG15 (n =64) | −0.03 | 0.84 | −0.04 | 0.79 | 0.27a | 0.04 | 0.52 | <0.0001 | 0.56 | <0.0001 |

| OAS3 (n =44) | −0.19 | 0.22 | −0.12 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.01 |

| RSAD2 (n =43) | −0.16 | 0.31 | −0.05 | 0.76 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: IFN, interferon; ISG, interferon-stimulated gene.

Sample number varied for different qPCR targets, based on sufficient available amount of RNA.

For each bivariate correlation, the number of data points was the lower of the Ns for the two targets (interferon and ISG). Numbers in bold show the statistically significant correlations between IFNs and ISGs. P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

To determine whether this association applies to global ISG expression, we analyzed the hepatic mRNA levels of 86 ISGs, quantified using the nCounter assay, in 23 patients and calculated the correlation coefficients between hepatic expressions of individual ISGs and IFNs. Nearly all of the ISGs (84/86) were positively correlated with IFNL2/3 (Supplementary Table 1), with 73% (63/86) showing a correlation above 0.43 (majority 0.5–0.86). Similar findings were seen for the correlation with IFNL1 (data not shown). In contrast, only 45% (39/86) and 64% (55/86) of ISGs had a positive correlation with IFNA1 or IFNG, respectively, and a correlation coefficient>0.3 was only seen in 5% (4/86) of ISGs for IFNA1 and 12% (10/86) for IFNG. Thus, in untreated HCV patients, hepatic ISGs are closely correlated with the expression of type III, but not with type I or II IFNs.

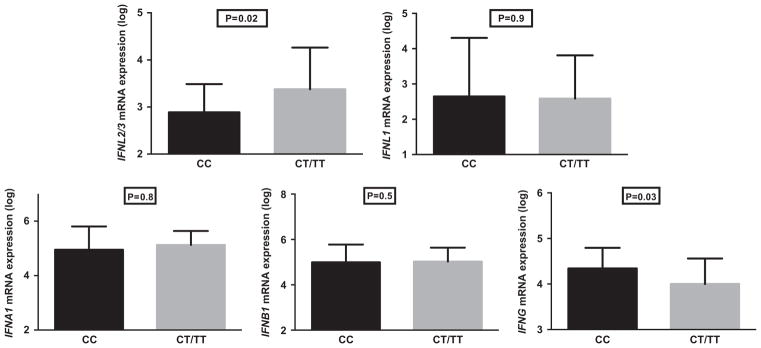

Hepatic expression of IFNs and ISGs and IFNL3 rs12979860 polymorphism

There was no difference between CC and CT/TT patients in terms of the hepatic expression of IFNL1 (P = 0.9), IFNA1 (P = 0.8) and IFNB1 (P = 0.5). In contrast, patients with the rs12979860 CC genotype had hepatic expression levels of IFNL2/3 that were on average 0.5 log10 lower compared with those with CT/TT (P = 0.02, Figure 3). In addition, patients with rs12979860 CC had IFNG levels that were 0.3 log10 higher than CT/TT patients (P = 0.03, Figure 3). The higher IFNG levels in CC patients, perhaps as a marker of infiltrating activated lymphocytes, is consistent with the previously reported higher hepatic inflammation associated with CC patients.26 Hepatic expression levels of ISG15 (4.9 log10 vs 5.3 log10) and a few other ISGs were lower in CC patients compared with CT/TT patients but the difference was not significant because of small sample size (for example: IFIT1: 4.0 log10 vs 4.6 log10; OAS3: 4.0 log10 vs 4.3 log10, RSAD2: 4 log10 vs 4.4 log10; IFI44: 3.8 log10 vs 4.1 log10).

Figure 3.

Hepatic expression of IFNs by IFNL3 genotype. Average hepatic expression of IFNs by qPCR (log-transformed arbitrary units) in patients with IFNL3 rs12979860 CC (29 patients) and CT/TT (36 patients) genotypes. Error bars denote s.d. P, Mann–Whitney test. P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

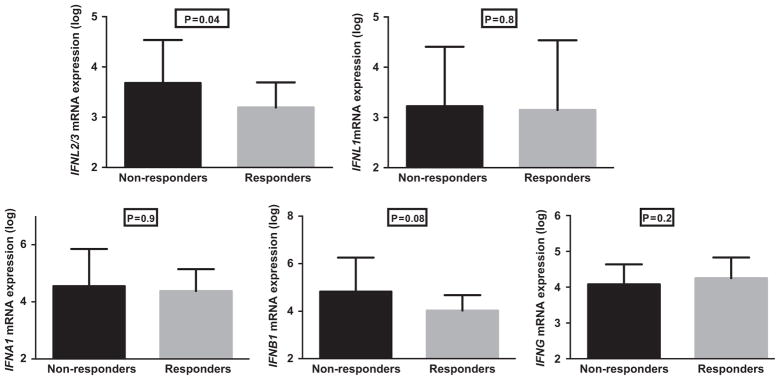

Hepatic expression of IFNs, ISGs and treatment response

Of the 65 patients in the cohort, 40 HCV genotype 1-infected patients who had been treated with Peg-IFN and ribavirin were included in the response-based analysis. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between responders and nonresponders (Supplementary Table 2). These 40 patients were part of a larger cohort of 199 HCV genotype 1-infected patients who were previously treated with Peg-IFN/ribavirin and were selected for this study based on the availability of a pre-treatment liver biopsy. As expected, the distribution of rs12979860 genotype in the larger treated cohort showed a significantly higher percentage of responders with the CC genotype (CC 32.8%, CT 50.8% and TT 16.4% in responders vs CC 10.1%, CT 42.7% and TT 47.2% in nonresponders; P<0.001). In the smaller cohort of 40 patients, the average baseline HCV viral load was 6.60 log10 IU ml −1 in nonresponders vs 6.16 log10 IU ml −1 in responders. Interestingly, the hepatic mRNA levels of IFNL2/3 were 0.5 log lower in responders compared with nonresponders (P = 0.04) prior to treatment but no differences were detected in the hepatic expression levels of the other IFNs (Figure 4). ISG expression was lower in responders compared with nonresponders but the difference did not reach statistical significance, again possibly reflecting the small sample size drawn from the larger cohort. The above analysis showed a similar trend when the patients were divided into nonresponders, relapsers and responders, but did not reach statistical significance probably because of small sample size.

Figure 4.

Hepatic expression of IFNs by treatment response. Hepatic expression of IFNs by qPCR in 22 responders and 18 nonresponders to IFN-based therapy. P, Mann–Whitney test. Nonresponders were defined as those who were treated with Peg-IFN and ribavirin with adequate doses for a minimum of 12 weeks but did not achieve a 2-log reduction in viral load by week 12 of treatment or had detectable virus by the end of treatment. Responders were defined as those who were treated with standard IFN or Peg-IFN in combination with ribavirin and achieved an end-of-treatment response, including those who achieved a sustained virologic response and those who relapsed after stopping treatment. P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

Effect of Peg-IFN injection on hepatic expression of IFNs and ISGs

Liver biopsies were obtained from 26 patients with CHC who had a liver biopsy 6 h after the first Peg-IFN injection.27 Similar to pre-treatment data, there was a robust correlation in post-injection biopsies within type I IFNs (IFNA1 vs IFNB1, r = 0.96; P = 0.0001) and type III (IFNL2/3 vs IFNL1, r = 0.85; P = 0.0001, Figure 5). However, in contrast to pre-treatment biopsies, there was a modest correlation between the levels of type I and type III IFNs (Figure 5). IFNG mRNA levels did not correlate with the other IFNs in the post-IFN samples (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Pair-wise correlations between hepatic expression levels of IFNs after Peg-IFN injection. Hepatic expression of IFNs, measured by qPCR (log-transformed arbitrary units) in 26 liver samples obtained 6 h post Peg-IFN injection and pair-wise correlations (Spearman’s r). P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

We then compared hepatic expression of IFNs between baseline and post Peg-IFN samples. IFNL2/3 expression was higher by 0.7 log10 (P = 0.0001) and IFNG levels were higher by 0.5 log10 (P = 0.0002), whereas IFNB1 levels were lower by 0.5 log10 (P = 0.00012) in post Peg-IFN samples. The levels of IFNL1 and IFNA1 were not significantly different (Supplementary Figure 1). As expected, hepatic ISG expression levels were higher in post Peg-IFN samples (Supplementary Figure 2). Finally, although IFNL2/3 expression at baseline specimens was lower in subjects with rs12979860 CC compared with CC/TT, its post-Peg-IFN levels were similar, suggesting a greater magnitude of induction by exogenous IFN in the CC subjects (Supplementary Figure 3).

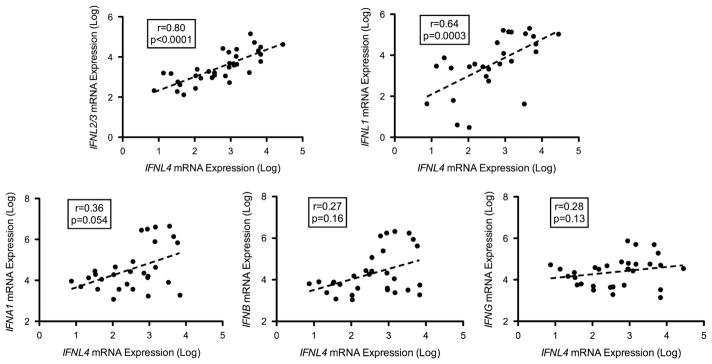

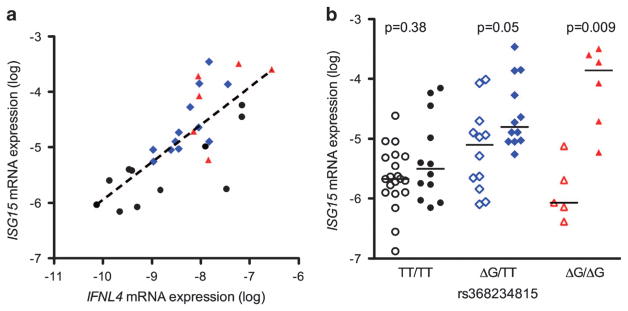

IFNL4 expression and its correlation with other IFNs and ISGs

We assessed the hepatic baseline expression of the IFNL4 gene transcripts, the rs368234815 genotype and their association with other IFNs and ISGs. The IFNL4 transcripts were assayed in 70 liver biopsy samples (65 of the previously described set with 5 additional samples) and were detectable in 33 (47%) of them. IFNL4 transcript levels were strongly correlated with those of type III IFNs, IFNL2/3 (r = 0.80, P<0.001) and IFNL1 (r = 0.64, P = 0.0003), and weakly associated with IFNA1 (r = 0.36, P = 0.054) but not with IFNB or IFNG (Figure 6). Similar to the other type III IFNs, hepatic IFNL4 transcript levels were closely correlated with those of ISG15 (r = 0.73, P<0.001) (Figure 7a), IFIT1 (r = 0.49, P = 0.009), OAS3 (r = 0.63, P = 0.003), RSAD2 (r = 0.54, P = 0.015) and IFI44 (r = 0.55, P = 0.01). Furthermore, in patients homozygous for the rs368234815 ΔG allele (predicted to express the IFN-λ4 protein), detectable expression of IFNL4 was associated with higher levels of ISG15 (Figures 7b, P = 0.009), whereas this was not the case for patients with TT/TT genotype (expressing a non-translated transcript, P = 0.38). Heterozygotes with TT/ΔG genotype demonstrate an intermediate pattern (P = 0.05). Finally, carriers of the ΔG allele were more likely to be nonresponders to Peg-IFN/RBV treatment (ΔG/ΔG+ΔG/TT (69%) vs TT/TT (31%) in nonresponders compared with ΔG/ΔG+ΔG/TT (47%) vs TT/TT (53%) in responders) but this did not reach statistical significance likely because of the small sample size of 40 patients.

Figure 6.

Correlations between hepatic expression levels of IFNL4 and other IFNs. Hepatic mRNA expression of IFNL4 transcript was analyzed for correlation with IFNL2/3, IFNL1, IFNA1, IFNB1 and IFNG, measured by qPCR. All measurements are in log-transformed arbitrary units. Correlations expressed as Spearman’s r. P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

Figure 7.

Effect of IFNL4 on ISG expression. (a) Correlation between hepatic expression of ISG15 and IFNL4 according to rs368234815 genotype (r =0.73, P<0.001). Black dot denotes rs368234815TT/TT, blue diamond TT/ΔG and red triangle ΔG/ΔG. (b) Hepatic expression of ISG15, stratified by rs368234815 genotype and whether IFNL4 gene transcripts were detectable (filled symbols) or not detectable (open). Lines denote means. P-value was considered significant if <0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we studied in great detail the relationship between hepatic expression of IFN types I, II, III and ISGs and response to treatment in a large cohort of CHC patients. We demonstrated, by using both qPCR and the nCounter platform, that hepatic ISG expression is strongly associated with hepatic type III expression but not type I IFNs at baseline. ISG levels were lower in patients with IFNL3 genotype CC compared with non-CC. Interestingly, hepatic expression levels of IFNL2/3 were lower in IFNL3 genotype CC compared with non-CC, whereas hepatic levels of IFNL1, IFNA1, IFNB1 and IFNG had no correlation with IFNL3 genotypes. In addition, hepatic expression levels of IFNL2/3 and ISGs were lower in responders compared with nonresponders, whereas the hepatic expression of IFNL1, IFNA1, IFNB1 and IFNG did not differ. Similarly, IFNL4 transcripts levels correlated with IFNL1 and IFNL2/3 (type III IFN) mRNA levels but not with type I or type II IFN levels. IFNL4 ΔG showed correlation with high ISG levels and likelihood of nonresponse to Peg-IFN and ribavirin. These data strongly support that hepatic IFNL2/3 expression and IFNL4 transcripts are primarily responsible for the induction of ISGs in response to HCV infection.

Honda et al.20 showed correlation between IFNL3 genotype and mRNA levels with ISGs, although no differences in hepatic expression of IFNL2/3 were demonstrated between the different genotypes. They postulated that such differences were not detected owing to low IFNL2/3 expression levels and the lack of availability of specific primers. Urban et al.25 also found no association between IFNL3 mRNA levels and treatment response. On the other hand, Dill et al.21 demonstrated that low hepatic expression levels of IFNL3 but high levels of ISGs were associated with the rs12979860 TT genotype (treatment unfavorable genotype), although this relationship was not found to be significant in analysis of IFNL3 rs8099917 SNP. They noted that the lower hepatic expression levels of IFNL3 in the rs12979860 TT genotype are consistent with the previous findings in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.11,28 Such a comparison is difficult to interpret because IFN response in the liver vs peripheral blood mononuclear cells could be quite different and HCV infects the liver only.29–32 The authors also found that IFNL3 genotype and hepatic ISG expression are independent predictors of response to treatment. It has been shown previously that type III IFN causes more prolonged ISG production than type I IFN in Huh 7.5 hepatoma cells.33 In a subsequent study from the same group, the authors were able to measure the levels of IFNL2/3 in only half of the samples and mostly at low expression levels from human livers with CHC and were not able to measure the levels of IFNL4.34 In that study, they found that the IFNL3 receptor IFNLR1 expression correlated with high ISGs expression levels and nonresponse to Peg-IFN and ribavirin. They concluded that the receptor IFNLR1 is responsible for the association with IFNL2/3 genotype and treatment response. Such a conclusion is apparently affected by the fact that they were not able to detect the IFNL3 and IFNL4 levels accurately. Indeed, the high pretreatment expression level of IFNL2/3 that we found in our study and its association with high ISG expression levels and with nonresponse would have been the best explanation to the elevated IFNLR1 expression. In contrast, several recent studies showed that hepatic IFNL3 mRNA levels were actually lower in patients with the IFNL3 favorable genotype (CC for rs12979860 and TT for rs80999917), and in responders compared with nonresponders.22–24 Many of the studies, however, were potentially plagued by technical difficulties with regard to quantification of IFNL2/3 levels and limited gene expression assessment.

To address this controversy, we investigated liver biopsy samples from a large cohort of CHC patients using qPCR and nCounter platform, which can be used to cross-validate the results. We also systematically analyzed the hepatic levels of all types of IFNs and a large number of ISGs, and performed detailed association studies among the levels of these genes, which to our knowledge has not been done in previous studies. Finally, we examined these associations after Peg-IFN injection to further explore the relationship between IFN types I, II, III and ISGs. Previously, we found a robust correlation between hepatic expression of IFNL2/3 and ISGs both in vitro and in vivo.7 Following infection of chimpanzees with HCV, hepatic type III IFNs were highly induced, which was associated with upregulation of ISGs, whereas only minimal induction of type I IFNs.19 In this study a large cohort of CHC patients,7 we found a similarly strong correlation between the hepatic expression of ISGs and the type III IFNs (IFNL2/3 and IFNL1), but not with other types of IFNs. These data collectively support the crucial role of type III IFNs in hepatic response to HCV infection and IFN-α mediated viral clearance.

On the basis of our data, the higher level expression of type III IFN that is associated with the non-favorable IFNL3 genotype is probably responsible for the higher ISG expression in HCV-infected liver. This higher baseline level of ISGs likely contributes to an IFN-refractory state in the liver, thus blunting further antiviral action of exogenous Peg-IFN administration. We previously postulated that this IFN-refractory state may be partially caused by ongoing endogenous IFN action and induction of IFN inhibitory pathways.35 Both IFNL2/3 and IFNL1 cause a prolonged induction of ISG expression compared with type I IFNs in cell culture model.7 Therefore, it is plausible that the continued presence of type III IFNs in the liver as an endogenous response to HCV infection predisposes the liver to an IFN-refractory state. The higher the endogenous levels of IFNL2/3 are, the more IFN-refractory the liver behaves. Recent studies also supported that USP18, a highly induced ISG, negatively affects the signaling pathway of type I IFN receptor complex.36 High hepatic USP18 level is also strongly predictive of treatment nonresponse.9

It is interesting to note that type III IFNs behave like ISGs and can be induced by exogenous Peg-IFN in vivo. We have previously shown that IFNL2/3 and IFNL1 can indeed be induced by IFN-α treatment in primary human hepatocytes.7 It is not clear whether this induction has any biological relevance in the antiviral action of Peg-IFN administration.

The role of IFNL4 remains largely undefined in HCV infection. It has been shown that IFNL4 transcript can be induced by poly-IC treatment in primary human hepatocytes and it can activate IFN signaling resulting in ISG induction.15 However, the level of IFNL4 expression, even when induced, is very low. Using a highly sensitive qPCR method, we could detect IFNL4 RNA transcripts only in about half of the liver samples. Interestingly, when we analyzed the correlation of hepatic IFNL4 and ISG levels according to the rs368234815 genotypes (TT/TT, TT/ΔG, ΔG/ΔG), we observed that only in the ΔG/ΔG genotype (where the presumably functional IFNL4 transcript is expressed), ISG expression was higher in samples with detectable IFNL4 mRNA, suggesting that IFNL4 may also contribute to ISG induction in HCV-infected liver. Our data confirm the previous findings by Amanzada et al.37 where the hepatic level of IFNL4 was detected in half of a smaller cohort of HCV patients (45 patients) and correlated with ISGs levels. In contrast to Amanzada et al., we found that the hepatic IFNL4 levels correlated well with the levels of other type III IFNs, suggesting a coordinated expression of all IFNLs. It is not unexpected that this is the case, because they are all located in the same locus on chromosome 19.15 We have also found that the IFNL4 ΔG allele correlated with nonresponse to Peg-IFN and ribavirin confirming the results of recent studies.15,16 Indeed, IFNL3 genotype has been shown to play a role in predicting response to IFN-free therapy, suggesting IFNL may still be relevant in DAA-mediated treatment response.38

Our study provides a functional link of IFNL3 genetic polymorphisms to hepatic expressions of type III IFNs and ISGs, and IFN-induced treatment response. Although IFN may play a diminishing role in future therapy of hepatitis C, the role of type III IFNs and IFNL4 in HCV infection is still an intriguing and largely unsolved biological question. New data from DAA therapies still suggest a role of endogenous IFN in treatment response. This is particularly important as investigating the relationship between IFNs (IFNL2/3 and IFNL4), ISGs and treatment response to DAA may lead to shortening the duration of treatment and cost-saving. Further exploration of the role of IFNL2/3, IFNL4 genotyping and expression levels in treatment response may shorten treatment and be used to individualize therapeutic options and optimize treatment management in IFN-free regimen. Understanding the mechanisms of these interactions among IFNs, HCV infection and viral clearance will provide further insight into the pathogenesis and improved management of hepatitis C.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patients

Sixty-five patients were selected from a large cohort of CHC patients followed at the Liver Clinic at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (NIH) (n = 712) and included in this retrospective analysis based on the availability of adequate stored liver biopsy specimen for analysis. We excluded patients with other causes of liver diseases (including HBV or HIV co-infection), excessive alcohol consumption, decompensated liver disease, active substance abuse or severe systemic disease. All patients gave written informed consent for participation in clinical research and genetic testing. The study was approved by the NIDDK/NIH Institutional Review Board.

Treatment response analysis

This analysis was limited to HCV genotype 1 patients, treated with IFN- and ribavirin-based therapies at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center who had adequate stored liver biopsy specimen. Patients were defined as nonresponders if they were treated with Peg-IFN and ribavirin with adequate doses for a minimum of 12 weeks but did not achieve a 2-log reduction in viral load by week 12 of treatment or had detectable virus by the end of treatment.2 Patients were defined as responders if they were treated with standard IFN or Peg-IFN in combination with ribavirin and achieved an end-of-treatment response, including those who achieved a sustained virologic response and those who relapsed after stopping treatment. We combined responders and relapsers for the sake of this analysis, as they represent on-treatment response and probably more accurately reflect the biology of host response to HCV infection. Patients who stopped treatment because of side effects or did not receive an adequate duration of treatment per protocol were excluded from this analysis. There were 40 patients available for this analysis.

Response to Peg-IFN injection

To further explore the functional associations between IFNs, ISGs and treatment response, we studied their associations in an additional set of CHC patients, who underwent a liver biopsy 6 h after their first Peg-IFN injection (180 mcg subcutaneous). They were a subset of patients with available stored liver tissue from a clinical trial (clinicatrials.gov registration NCT00718172) where patients were randomized to undergo a liver biopsy prior to or after Peg-IFN injection (6 h after injection).27

Sample processing and qPCR

Immediately following a percutaneous liver biopsy, a 2–5-mm sample was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen or placed in RNALater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and stored in −80 °C for later analysis. Total RNA was extracted from the frozen samples using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and treated with DNAse. cDNA synthesis was performed using 0.3–0.5 μg of total RNA (Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using an ABI 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and TaqMan gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems). IFNL2/3 mRNA levels were measured as previously described,7 with primers that do not differentiate IFNL2 from IFNL3. IFNL4 mRNA expression was measured using custom-made primers and probe (Applied Biosystems) as detailed in the Supplementary Methods. Expression of other target genes was quantified using primers and probes that were previously described.7 The mRNA levels, determined using a FAM-Labeled TaqMan Probe, are normalized to the 18S ribosomal RNA levels in each PCR reaction using the eukaryotic 18S rRNA endogenous control from ABI (VIC/MGB Probe, Primer Limited, Cat# 4319413E) and expressed in relative units.

Global ISG expression

In a subgroup of 23 patients, global hepatic expression of ISGs was quantified using the nCounter Gene Expression assay (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA),39 using a custom code-set of 136 ISGs, designed as previously described.27 Total RNA (100 ng) from the liver biopsy samples were utilized and the results were normalized by the expression of four housekeeping genes. To avoid spurious associations, we limited the analysis to 86 genes that had average expression levels at least 1 log greater than the limit of detection.

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Qiagen Flexigene DNA Kit (Qiagen). The rs12979860 SNP was genotyped by allelic discrimination using a TaqMan Custom SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). rs368234815 was genotyped by Sanger sequencing using BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, or by allelic discrimination using a TaqMan Custom SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems) as previously described.15

Statistical analysis

Variables are reported as mean ± s.d. The chi-square (χ2) test was used for comparisons between categorical variables, and t-test or Mann-Whitney (as appropriate) were used to compare continuous variables. Correlations were examined using Spearman’s Rho (Rho was abbreviated as r in the figures) on log-transformed data. Logistic regression and goodness-of-fit were calculated by the least-squares method. GraphPad Prism version 5.0b (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and SPSS Statistics version 19 (IBM, Somers, NY, USA) were used. A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK, NIH.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Genes and Immunity website (http://www.nature.com/gene)

References

- 1.Seeff LB. The history of the “natural history” of hepatitis C (1968–2009) Liver Int. 2009;29(Suppl 1):89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1907–1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1213651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Therapy of Hepatitis C - Back to the Future. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2043–2047. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1403619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meissner EG, Wu D, Osinusi A, Bon D, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant D, et al. Endogenous intrahepatic IFNs and association with IFN-free HCV treatment outcome. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3352–3363. doi: 10.1172/JCI75938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meissner EG, Bon D, Prokunina-Olsson L, Tang W, Masur H, O’Brien TR, et al. IFNL4-DeltaG genotype is associated with slower viral clearance in hepatitis C, genotype-1 patients treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1700–1704. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas E, Gonzalez VD, Li Q, Modi AA, Chen W, Noureddin M, et al. HCV infection induces a unique hepatic innate immune response associated with robust production of type III interferons. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:978–988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarasin-Filipowicz M, Oakeley EJ, Duong FH, Christen V, Terracciano L, Filipowicz W, et al. Interferon signaling and treatment outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7034–7039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707882105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Borozan I, Feld J, Sun J, Tannis LL, Coltescu C, et al. Hepatic gene expression discriminates responders and nonresponders in treatment of chronic hepatitis C viral infection. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O’Huigin C, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, Cai T, Di Iulio J, Mueller T, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1338–1345 45. e1–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prokunina-Olsson L, Muchmore B, Tang W, Pfeiffer RM, Park H, Dickensheets H, et al. A variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nat Genet. 2013;45:164–171. doi: 10.1038/ng.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bibert S, Roger T, Calandra T, Bochud M, Cerny A, Semmo N, et al. IL28B expression depends on a novel TT/-G polymorphism which improves HCV clearance prediction. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1109–1116. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFarland AP, Horner SM, Jarret A, Joslyn RC, Bindewald E, Shapiro BA, et al. The favorable IFNL3 genotype escapes mRNA decay mediated by AU-rich elements and hepatitis C virus-induced microRNAs. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:72–79. doi: 10.1038/ni.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balagopal A, Thomas DL, Thio CL. IL28B and the control of hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1865–1876. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park H, Serti E, Eke O, Muchmore B, Prokunina-Olsson L, Capone S, et al. IL-29 is the dominant type III interferon produced by hepatocytes during acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2012;56:2060–2070. doi: 10.1002/hep.25897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda M, Sakai A, Yamashita T, Nakamoto Y, Mizukoshi E, Sakai Y, et al. Hepatic ISG expression is associated with genetic variation in interleukin 28B and the outcome of IFN therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:499–509. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dill MT, Duong FH, Vogt JE, Bibert S, Bochud PY, Terracciano L, et al. Interferon-induced gene expression is a stronger predictor of treatment response than IL28B genotype in patients with hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1021–1031. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abe H, Hayes CN, Ochi H, Maekawa T, Tsuge M, Miki D, et al. IL28 variation affects expression of interferon stimulated genes and peg-interferon and ribavirin therapy. J Hepatol. 2011;54:1094–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abe H, Hayes CN, Ochi H, Tsuge M, Miki D, Hiraga N, et al. Inverse association of IL28B genotype and liver mRNA expression of genes promoting or suppressing antiviral state. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1597–1607. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asahina Y, Tsuchiya K, Muraoka M, Tanaka K, Suzuki Y, Tamaki N, et al. Association of gene expression involving innate immunity and genetic variation in interleukin 28B with antiviral response. Hepatology. 2012;55:20–29. doi: 10.1002/hep.24623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urban TJ, Thompson AJ, Bradrick SS, Fellay J, Schuppan D, Cronin KD, et al. IL28B genotype is associated with differential expression of intrahepatic interferon-stimulated genes in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;52:1888–1896. doi: 10.1002/hep.23912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noureddin M, Wright EC, Alter HJ, Clark S, Thomas E, Chen R, et al. Association of IL28B genotype with fibrosis progression and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a longitudinal analysis. Hepatology. 2013;58:1548–1557. doi: 10.1002/hep.26506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotman Y, Noureddin M, Feld JJ, Guedj J, Witthaus M, Han H, et al. Effect of ribavirin on viral kinetics and liver gene expression in chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2014;63:161–169. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier V, Mihm S, Ramadori G. Interferon-alpha therapy does not modulate hepatic expression of classical type I interferon inducible genes. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1912–1918. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarasin-Filipowicz M, Wang X, Yan M, Duong FH, Poli V, Hilton DJ, et al. Alpha interferon induces long-lasting refractoriness of JAK-STAT signaling in the mouse liver through induction of USP18/UBP43. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4841–4851. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00224-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanford RE, Guerra B, Lee H, Chavez D, Brasky KM, Bigger CB. Genomic response to interferon-alpha in chimpanzees: implications of rapid downregulation for hepatitis C kinetics. Hepatology. 2006;43:961–972. doi: 10.1002/hep.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujiwara D, Hino K, Yamaguchi Y, Kubo Y, Yamashita S, Uchida K, et al. Type I interferon receptor and response to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients: a prospective study. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:136–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcello T, Grakoui A, Barba-Spaeth G, Machlin ES, Kotenko SV, MacDonald MR, et al. Interferons alpha and lambda inhibit hepatitis C virus replication with distinct signal transduction and gene regulation kinetics. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1887–1898. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duong FH, Trincucci G, Boldanova T, Calabrese D, Campana B, Krol I, et al. IFN-lambda receptor 1 expression is induced in chronic hepatitis C and correlates with the IFN-lambda3 genotype and with nonresponsiveness to IFN-alpha therapies. J Exp Med. 2014;211:857–868. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feld JJ, Nanda S, Huang Y, Chen W, Cam M, Pusek SN, et al. Hepatic gene expression during treatment with peginterferon and ribavirin: Identifying molecular pathways for treatment response. Hepatology. 2007;46:1548–1563. doi: 10.1002/hep.21853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randall G, Chen L, Panis M, Fischer AK, Lindenbach BD, Sun J, et al. Silencing of USP18 potentiates the antiviral activity of interferon against hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1584–1591. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amanzada A, Kopp W, Spengler U, Ramadori G, Mihm S. Interferon-lambda4 (IFNL4) transcript expression in human liver tissue samples. PloS One. 2013;8:e84026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petta S, Cabibbo G, Enea M, Macaluso FS, Plaia A, Bruno R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based triple therapy for untreated patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2014;59:1692–1705. doi: 10.1002/hep.27010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geiss GK, Bumgarner RE, Birditt B, Dahl T, Dowidar N, Dunaway DL, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.