Abstract

Background

Heart failure results in significant morbidity and mortality for young children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) following the Norwood procedure.

Methods

We studied subjects enrolled in the prospective Single Ventricle Reconstruction (SVR) trial who survived to hospital discharge after the Norwood operation and were followed up to age 6 years. The primary outcome was heart failure, defined as heart transplant listing after Norwood hospitalization, death attributable to heart failure or symptomatic heart failure (NYHA class IV). Multivariate modeling was undertaken using Cox regression methodology to determine variables associated with heart failure.

Results

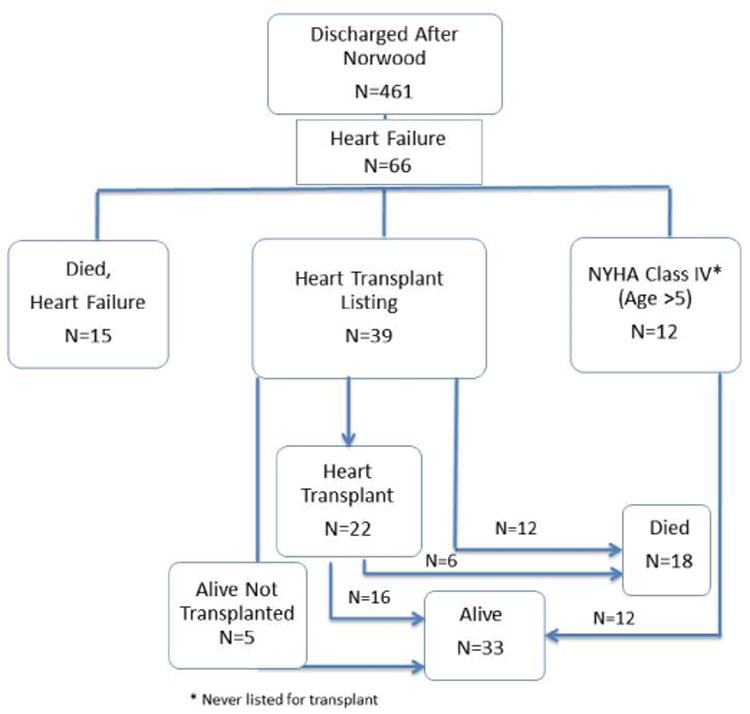

Of the 461 subjects discharged to home following Norwood procedure, 66 (14.3%) met criteria for heart failure. Among these, 15 died from heart failure, 39 were listed for transplant (22 had a transplant, 12 died after listing and 5 were alive and not yet transplanted), and 12 had NYHA Class IV heart failure but were never listed. The median age at heart failure identification was 1.28 yrs (interquartile range 0.30 - 4.69 years). Factors associated with heart failure included post-Norwood lower fractional area change, need for ECMO, non-Hispanic ethnicity, Norwood perfusion type and total support time (p<0.05).

Conclusions

By 6 years of age heart failure develops in nearly 15% of children following Norwood procedure. Even though transplant listing was common, many died from heart failure before receiving a transplant or without being listed. Shunt type did not impact the risk of developing heart failure.

Clinical Trial Registration

Registered with ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00115934 URL: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00115934

Keywords: congenital heart defect, congenital heart disease, cardiac surgery, single ventricle, Norwood procedure

Introduction/Background

The most common surgical treatment strategy for hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is the Norwood procedure.1 This palliative procedure has been used for over 35 years. The survival following the Norwood procedure has improved over time such that the 5-year survival now exceeds 60%.2,3 However, a significant proportion of children will develop heart failure following the Norwood procedure.

It is clear that heart failure in the single ventricle population often necessitates listing for heart transplantation.4,5,6,7 Existing registries only capture data once children are listed for transplantation. Children with contraindications to heart transplantation or those who die from heart failure prior to listing for transplant are not included in such analyses. Some preliminary studies have suggested that the type of pulmonary artery shunt, i.e. right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt (RVPAS) versus modified Blalock-Taussig shunt (MBTS), may impact the likelihood of developing right ventricular failure.8,9 In addition, little is known about children who are medically managed with symptomatic heart failure following the Norwood procedure.

The Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial (SVR) and the follow-up extension study (SVR II) provide a unique opportunity to define the heart failure term and to enhance our understanding of heart failure following the Norwood procedure. Previous analysis from the SVR cohort demonstrated that subjects who underwent Norwood procedure with RVPAS, as compared to those with the MBTS, had increased RV end-systolic volume and decreased right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) from the 14-month to pre-Fontan echocardiogram. However, it is not known how these echocardiographic findings relate to the clinical onset of heart failure. A detailed knowledge of the course of heart failure following the Norwood procedure can aid in determining if, and when, children with right ventricular failure should be considered for heart transplantation. Therefore, we sought to determine the incidence of heart failure in young children following the Norwood procedure. We also explored the risk factors for development of heart failure, including echocardiographic findings at Norwood hospital discharge.

Methods

The SVR trial in infants undergoing the Norwood procedure randomly assigned subjects to either the MBTS or the RVPAS at 15 North American centers.10 The study design permitted collection of extensive data from hospitalizations and subsequent follow-up assessments. Following the Norwood procedure but prior to hospital discharge, all subjects had a comprehensive echocardiogram evaluated at a central core laboratory for various measures including fractional area change and tricuspid regurgitation.11 The present analysis was limited only to those subjects who survived to hospital discharge following the Norwood procedure without transplant listing and includes all available follow-up until the last subject reached 6 years of age via the SVR Extension Study. The Institutional Review Board of each participating center approved this study, and parents/guardians of enrolled subjects provided informed consent.

Data were prospectively collected on heart failure symptoms and medical events, including listing for heart transplantation and, where applicable, subsequent transplantation. In the current study, heart failure was defined as having at least one of the following: listing for heart transplantation, death attributed to heart failure, or New York Heart Association (NYHA) Heart Failure class IV.

To verify the classification of death due to heart failure, study investigators reviewed the annual vital status form records of all subjects whose primary cause of death had been attributed to heart failure. Heart failure symptoms were determined from annual follow-up by study coordinators using medical records and patient interviews. Heart failure symptoms were categorized according to the NYHA class in years 5 and 6. Classification of symptomatic heart failure in those younger than 5 years was not undertaken owing to limitations of such scoring systems in the very young. The follow-up was limited to the 6-year annual assessment.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical methods are similar to those previously used in analysis of SVR data at 3 years.2 The comparison of study outcomes was according to treatment assignment to MBTS or RVPAS (intention-to-treat) unless otherwise specified. To assess for associations between echocardiographic findings and the subsequent development of heart failure, we utilized the protocol-mandated echocardiogram obtained following the Norwood procedure but before hospital discharge. We used a Wald test for comparison of 6-year event rates estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the log rank test to determine the distributions of time to the earliest occurrence of advanced heart failure using all available follow-up. Three subjects had their follow-up time censored at the time of biventricular repair. For subjects who were followed past 6 years, the follow up was censored at 6 years. Onset of symptomatic heart failure (NYHA class IV) was defined as date annual form was completed. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify potential pre- and intra-operative risk factors for transplant-free survival. Because a test of non-proportionality indicated non-proportional hazards for several predictors, including shunt type, in multivariate modeling, we used Cox regression with a time-dependent treatment indicator. Separate models were run for subjects who developed heart failure at <1 year of age and ≥1 year of age. Multivariate modeling utilized a backwards selection method within each time interval, starting with predictors significant at level 0.20 in univariate analysis. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant in these multivariate models. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

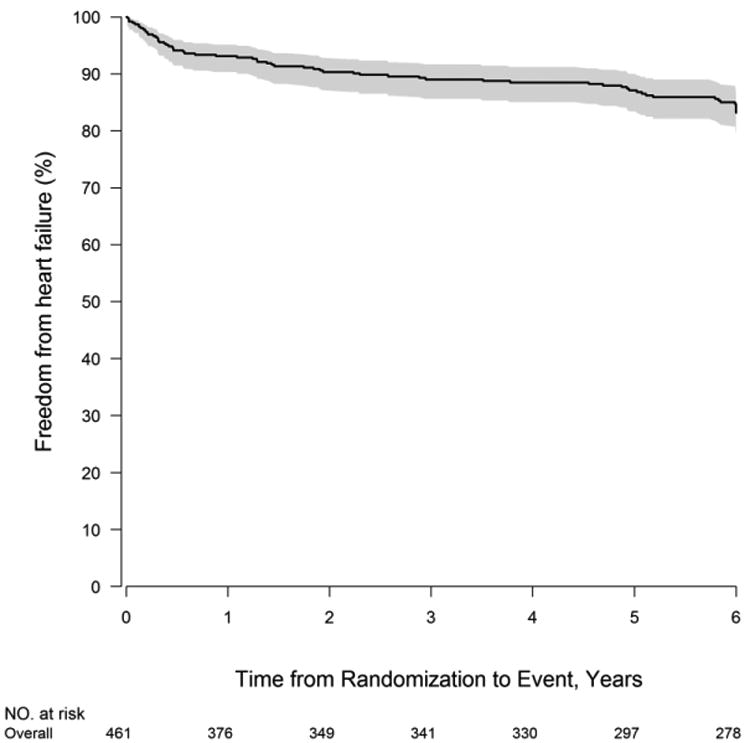

Of the 461 subjects discharged to home following the Norwood procedure without prior heart transplant listing, 226 had undergone an MBTS and 235 had undergone a RVPAS. During the follow-up period, 66 subjects (14.3%) subsequently met the definition of heart failure: heart transplant listing (n=39), NYHA class IV (n=12) or heart failure death (n=15) (Figure 1). Of the 353 subjects who survived to 6 years, 16 were post-transplant and of the remaining 337, 297 consented to the SVR extension trial and 287 completed the heart failure classification form. The heart failure criteria stratified by shunt type are shown in Table 1. Risk for developing heart failure was highest in the first year of life (Figure 2). After the first 12 months, the risk of developing heart failure was approximately 3% per year. The median age at heart failure onset was 1.28 years (interquartile range 0.30, 4.69 years). The median age for the various heart failure events is shown in Table 2. The median ages at heart failure, death or transplant listing were both less than 1 year. With respect to stage of palliation at time of first heart failure event, there were 21 between Norwood procedure and stage II, 28 between stage II and Fontan and 17 following Fontan. For transplant listing events there were 16 listed between Norwood procedure and stage II, 19 between stage II and Fontan and 4 following Fontan.

Figure 1.

Diagram depicting clinical pathways for subjects with advanced heart failure.

Table 1.

Heart Failure in SVR Subjects Using All Available Follow-up Data.

| All | MBTS | RVPAS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Heart Failure | 66/461 (14.3%) | 31/226 (13.7%) | 35/235 (14.9%) |

| Heart Transplant Listing | 39/461 (8.5%) | 19/226 (8.4%) | 20/235 (8.5%) |

| Listed & Not Transplanted | 17/39 (43.6%) | 9/19 (47.4%) | 8/20 (40.0%) |

| Listed & subsequent death | 12/17 (70.6%) | 6/9 (66.7%) | 6/8 (75.0%) |

| Listed & alive at 6 years without transplant | 5/17 (29.4%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | 2/8 (25.0%) |

| Listed & Transplanted | 22/39 (56.4%) | 10/19 (52.6%) | 12/20 (60.0%) |

| Transplanted & death before 6 years | 6/22 (27.3%) | 3/10 (30.0%) | 3/12 (25.0%) |

| Transplanted & alive at 6 years | 16/22 (72.7%) | 7/10 (70.0%) | 9/12 (75.0%) |

| Heart Failure Death | 15/461 (3.3%) | 7/226 (3.0%) | 8/235 (3.4%) |

| NYHA Class 4 in year 6* | 12/287 (4.2%) | 5/141 (3.5%) | 7/146 (4.8%) |

The event status is reported as whether they ever had that event or not.

There 337 transplant free survivors at their 6 years age, of which 297 of were consented to SVR Extension study. Of these, 287 completed the heart failure classification form.

Figure 2.

Freedom from heart failure using all available follow-up data until 6 years (72 Months). Heart failure was defined as listing for heart transplantation, heart failure death, or NYHA Heart Failure Class IV.

Table 2. Follow-up Time from Norwood Discharge (years) for Heart Failure in SVR Subjects.

| Event | Follow-up time, years Median (Interquartile Range) |

|---|---|

| First Heart Failure (n=66) | 1.28 (0.30, 4.69) |

| Heart Transplant Listing* (n=37) | 0.88 (0.28, 2.23) |

| Heart Failure Death (n=15) | 0.57 (0.21, 1.84) |

Two subjects were not included due to missing listing date.

Twelve participants died after heart transplant listing (12/39, 30.8%) but before receiving a transplant. The mean time interval between heart transplant listing and death for the 12 patients who died pre-transplant was 0.29±0.30 years. Twenty-two subjects received a heart transplant. The mean interval from listing to heart transplant was 0.25±0.40 years. Of the 22 subjects who underwent heart transplant, 6 died after transplant, and 16 were alive at 6 years of age. For the 6 patients who died after transplant, the time interval between heart transplant and post-transplant death was 0.09±0.13 years.

Among the 353 subjects surviving to 6-year follow-up, 287 completed the NYHA classification assessment, of which 12 subjects (4.2%) had NYHA Class IV heart failure. These 12 subjects were managed with a variety of medications including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) in 6, digoxin in 3, diuretics in 3 and sildenafil in 1. No patients were receiving beta-blockers. Three subjects with NYHA Class IV heart failure were reported to not be receiving any conventional heart failure medications.

As the risk of developing heart failure varied by time since the Norwood procedure, two separate risk models were constructed. Risk factors associated with the development of early advanced heart failure (< 1 year) included perfusion and perioperative factors such as need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) at end of Norwood operation and use of predominant regional cerebral perfusion rather than deep hypothermic circulatory arrest during the Norwood operation (Table 3). A lower fractional area change on the post-Norwood echo was associated with an increased risk of early heart failure. Additional risk factors for early heart failure included non-Hispanic ethnicity and shorter total bypass time. The only perioperative factor associated with late heart failure (>1 yr) was the use of α-blockade at the time of the Norwood procedure, which was associated with a lower risk of late heart failure, HR=0.29 (0.14, 0.60). Anatomic variant of HLHS was not associated with the development of heart failure. Shunt type was not associated with the development of heart failure following Norwood hospital discharge.

Table 3. Multivariate Risk Model for Early Heart Failure (< 1 year).

| Characteristics | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Hispanic yes vs. no | 0.28 (0.09,0.93) | 0.038 |

| Fractional area change. =<0.35 vs. >0.35 | 5.00 (1.37,18.22) | 0.015 |

| ECMO immediately following Norwood procedure | 5.83 (1.75,19.46) | 0.004 |

| Norwood Perfusion type | <0.001 | |

| DHCA only vs. RCP/DHCA with DHCA time>10 min | 0.05 (0.01,0.22) | |

| RCP and DHCA time<=10 min vs. RCP/DHCA with DHCA time>10 min | 0.96 (0.27,3.44) | |

| Total bypass time | 0.91 (0.87,0.95) | <0.001 |

The R2 for the model is the 0.607.

A list of all variables included in the univariate model is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

DHCA- deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; ECMO- extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; RCP-regional cerebral perfusion

Discussion

This study demonstrates that heart failure occurs not uncommonly in early childhood among children who undergo the Norwood procedure as young infants, and the risk of developing heart failure is greatest in infancy. Whereas many children are listed for and successfully undergo heart transplantation for severe heart failure, others die from heart failure while on the waitlist, or more often, without ever being listed. The number of children with heart failure who are managed medically at early school age is relatively low.

There has been concern regarding the impact of shunt type on the development of heart failure following the Norwood procedure because the RVPAS requires implantation of the proximal portion of the shunt directly into the RV free wall. Some have hypothesized that this would lead to local or global RV injury.13 Ballweg and colleagues reported a higher degree of impaired RV function in those children receiving an RVPAS as compared to a MBTS; 8however, the use of the two shunt types was not randomized, and those receiving the RVPAS were more likely to have aortic atresia. Frommelt and colleagues found that, on the echocardiogram performed between 14-months and the Fontan operation, the MBTS group had stable indexed RV volumes and ejection fraction, whereas the RVPAS group had increased RV end-systolic volume and decreased RV ejection fraction (RVEF).14 This raised concerns about an increased long-term risk for RV failure in the RVPAS cohort. Our present analyses demonstrated no differences between shunt groups in the composite measure of heart failure, or in transplant listing, symptomatic heart failure or death from heart failure following discharge from Norwood hospitalization. This provides reassuring information regarding medium-term adverse effects of the RVPAS and suggests that the decision to choose one shunt type over the other should be driven by factors other than risk of midterm heart failure. It is important to recognize, however, that the present analysis was limited to those subjects discharged to home following the Norwood procedure and hence does not provide insights into implications of shunt type or immediate post-Norwood heart failure.

Several factors were associated with the development of heart failure in the first year. These include perioperative factors such as the use of ECMO immediately following the Norwood procedure. Echocardiographic findings were also associated with the development of heart failure: a lower fractional area change at the time of Norwood hospital discharge was associated with early heart failure. This finding is logical and consistent with previously published literature.15,16 Surprisingly, Hispanic ethnicity was associated with a lower risk of early heart failure. The mechanisms to explain such a link remain unclear, and a p-value close to 0.05 in the context of multiple testing could indicate a chance finding. The use of predominant deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA), compared to predominant regional cerebral perfusion, was associated with a lower risk of developing heart failure. It is possible that this represents center variation that is not accounted for completely in the model. Fewer perioperative factors were associated with the development of heart failure beyond the first year. This suggests that clinical factors that come into play after discharge from the Norwood procedure, such as the perioperative stage II procedure course, the accommodation of the pulmonary vascular bed, and the development of volume loading lesions, may have a greater impact on the development of heart failure after the first year of life.

Eight percent of subjects were listed for heart transplant. The risk for heart transplant listing was greatest in the first 18 months of life, with the highest risk occurring immediately following Norwood hospital discharge. This may not be surprising, as early single ventricle hemodynamics are less favorable and the stage II procedure has the potential to reduce the volume load on the heart and create more efficient circulation.17 Heart failure and ventricular function often impact the decision on timing of stage II operation. In an analysis of the SVR cohort Schwartz et al found that ventricular dysfunction was the reason for an early stage II in 33 of the 199 (16.5%) non-elective cases.18 After the first 12 months, the risk of developing heart failure is approximately 3% per year. Whether this same hazard rate persists into later school age and adolescence remains to be determined. Previous studies have found the risk of death or transplant for those with HLHS is relatively low in the school-age group.19

Little is reported about symptomatic heart failure in young children with HLHS. We found only a small proportion of children with advanced symptomatic heart failure at age 6 years. One of the challenges of quantifying heart failure in young children relates to the standardized clinical measures. In the SVR trial, we administered the Ross heart failure score at 1, 2, 3 and 4 years of age; starting at age 5 years, we administered the NYHA scale. We found the Ross heart failure score to be too inconsistent to use as a reliable clinical endpoint. For this reason, we limited the analyses only to NYHA scores. We found that at 6 years, only 4.2% of children were NYHA class IV and not listed for heart transplant. This may reflect a strategy to list single ventricle patients for transplant once they reach stage IV heart failure rather than pursue medical management. 20, 21

Relatedly, our inability to reliably identify younger patients with advanced heart failure not listed for transplant, and our reliance on the NYHA classification for older children, limits the analysis in our study to children with very advanced heart failure, and it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding the incidence or management of mild to moderate heart failure in the SVR trial cohort.

While our sample size is small, we found that a number of therapeutic agents were used to manage those with class IV NYHA heart failure. These included ACE inhibitors, diuretics and digoxin. It is unclear which medical therapies should be employed to manage the child with severe heart failure.22 Surprisingly, none of the subjects were managed with a beta-blocker, and several subjects were not receiving any heart failure medications. This may reflect uncertainty as to the value of conventional heart failure medications in this population, particularly after two pediatric trials demonstrated minimal benefit of these medications in the congenital heart disease population.

We found that amongst subjects listed for heart transplantation, the waitlist mortality was 30.7%. This is consistent with previous registry data reporting high waitlist mortality for young children with congenital heart disease.23 Many factors account for this elevated waitlist mortality. Ventricular assist devices (VADs) are used much less commonly in the single ventricle population, and when they are used, success rates are low.24 In addition, patients palliated with the Norwood procedure have a high rate of allosensitization due to the use of allograft material and frequent transfusions of blood products25, which further limits donor availability. Many centers seek to reduce the risks conferred by allosensitization by a strategy of virtual crossmatching, which often requires longer waitlist times.26 The outcomes following transplant in this population with 72.7% of subjects surviving to 6 years of age are in keeping with published data. Young children with prior surgery for congenital heart disease are known to have increased risk of post-transplant mortality.27 The findings in this study support the recent modification of the heart transplant allocation system in the United States to prioritize those with congenital heart disease; modifications which took effect after the conclusion of the SVR trial.28

One of the strengths of the SVR trial is that all deaths had independent adjudication as to cause. This is important because most estimates of heart failure-related deaths come from clinical databases or administrative datasets with recognized limitations.29 Only very recently has a heart failure registry in children been established.30 Moreover in the single ventricle population, it cannot be assumed that every child with severe heart failure would come to heart transplant listing prior to death. Marked allosensitization, vascular complications, rapid deterioration or parental preferences may have precluded heart transplant listing. We found that among those children discharged to home following the Norwood procedure, the risk of heart failure death was highest in the first year. It is possible that prompt recognition of heart failure may have allowed some of these children to be stabilized, evaluated and listed for heart transplantation. However, heart failure progression in this population can be rapid and deterioration may still occur in some despite optimal medical care.31

In summary, heart failure occurs in nearly 15% of children who achieve discharge after the Norwood procedure. Among transplant-free survivors to 6 years of age, fewer than 5% of children with palliated HLHS have advanced symptomatic heart failure. Future follow-up of the SVR cohort is needed to investigate the risk of developing heart failure in later schoolage or adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants (HL068269, HL068270, HL068279, HL068281, HL068285, HL068288, HL068290, HL068292, and HL085057) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NHLBI or NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Single Ventricle Reconstruction Trial participants: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Gail Pearson, Victoria Pemberton, Rae-Ellen Kavey, Mario Stylianou, Marsha Mathis

Network Chair: Lynn Mahony, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Data Coordinating Center: New England Research Institutes, Lynn Sleeper (PI), Sharon Tennstedt (PI), Steven Colan, Lisa Virzi, Patty Connell, Victoria Muratov, Lisa Wruck, Minmin Lu, Dianne Gallagher, Anne Devine, Thomas Travison, David F. Teitel

Core Clinical Site Investigators: Boston Children's Hospital, Jane W. Newburger (PI), Peter Laussen, Pedro del Nido, Roger Breitbart, Jami Levine, Ellen McGrath, Carolyn Dunbar-Masterson; Children's Hospital of New York, Wyman Lai (PI), Beth Printz (currently at Rady Children's Hospital), Daphne Hsu (currently at Montefiore Medical Center), William Hellenbrand (currently at Yale New Haven Medical Center), Ismee Williams, Ashwin Prakash (currently at Children's Hospital Boston), Ralph Mosca (currently at New York University Medical Center), Darlene Servedio, Rozelle Corda, Rosalind Korsin, Mary Nash; Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Victoria L. Vetter (PI), Sarah Tabbutt (currently at the University of California, San Francisco), J. William Gaynor (Study Co-Chair), Chitra Ravishankar, Thomas Spray, Meryl Cohen, Marisa Nolan, Stephanie Piacentino, Sandra DiLullo, Nicole Mirarchi; Cincinnati Children's Medical Center, D. Woodrow Benson (PI), Catherine Dent Krawczeski, Lois Bogenschutz, Teresa Barnard, Michelle Hamstra, Rachel Griffiths, Kathie Hogan, Steven Schwartz (currently at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto), David Nelson; North Carolina Consortium, Duke University, East Carolina University, Wake Forest University, Page A. W. Anderson (PI; deceased), Jennifer Li (PI), Wesley Covitz, Kari Crawford, Michael Hines, James Jaggers, Theodore Koutlas, Charlie Sang, Jr, Lori Jo Sutton, Mingfen Xu; Medical University of South Carolina, J. Philip Saul (PI), Andrew Atz, Girish Shirali, Scott Bradley, Eric Graham, Teresa Atz, Patricia Infinger; Primary Children's Hospital and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, L. LuAnn Minich (PI), John Hawkins (deceased), Michael Puchalski, Richard Williams, Linda Lambert, Jun Porter, Marian Shearrow; Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Brian McCrindle (PI), Joel Kirsh, Chris Caldarone, Elizabeth Radojewski, Svetlana Khaikin, Susan McIntyre, Nancy Slater; University of Michigan, Caren S. Goldberg (PI), Richard G. Ohye (Study Chair), Cheryl Nowak; Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, Nancy Ghanayem (PI), James Tweddell, Kathy Mussatto, Michele Frommelt, Lisa Young-Borkowski

Auxiliary Sites: Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Alan Lewis (PI), Vaughn Starnes, Nancy Pike; The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida (CHIF), Jeffrey P. Jacobs, MD (PI), James A. Quintessenza, Paul J. Chai, David S. Cooper, J. Blaine John, James C. Huhta, Tina Merola, Tracey Cox; Emory University, Kirk Kanter, William Mahle, Joel Bond, Leslie French, Jeryl Huckaby; Nemours Cardiac Center, Christian Pizarro, Carol Prospero; Julie Simons, Gina Baffa; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Ilana Zeltzer (PI), Tia Tortoriello, Deborah McElroy, Deborah Town

Angiography core laboratory: Duke University, John Rhodes, J. Curt Fudge

Echocardiography core laboratories: Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, Peter Frommelt; Children's Hospital Boston, Gerald Marx

Genetics Core Laboratory: Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Catherine Stolle

Protocol Review Committee: Michael Artman (Chair); Erle Austin; Timothy Feltes, Julie Johnson, Thomas Klitzner, Jeffrey Krischer, G. Paul Matherne

Data and Safety Monitoring Board: John Kugler (Chair); Rae-Ellen Kavey; Executive Secretary; David J. Driscoll, Mark Galantowicz, Sally A. Hunsberger, Thomas J. Knight, Holly Taylor, Catherine L. Webb

References

- 1.Jacobs JP, Mayer JE, Jr, Mavroudis C, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database: 2017 Update on Outcomes and Quality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(3):699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Frommelt PC, et al. Transplantation-free survival and interventions at 3 years in the single ventricle reconstruction trial. Circulation. 2014;129(20):2013–2020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsoufi B, McCracken C, Shashidharan S, Kogon B, Border W, Kanter K. Palliation Outcomes of Neonates Born With Single-Ventricle Anomalies Associated With Aortic Arch Obstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(2):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alsoufi B, Deshpande S, McCracken C, et al. Results of heart transplantation following failed staged palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome and related single ventricle anomalies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48(5):792–798. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu547. discussion 798-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh TP, Milliren CE, Almond CS, Graham D. Survival benefit from transplantation in patients listed for heart transplantation in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs JP, Quintessenza JA, Chai PJ, et al. Rescue cardiac transplantation for failing staged palliation in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Cardiol Young. 2006;16(6):556–562. doi: 10.1017/S1047951106001223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkarni A, Neugebauer R, Lo Y, et al. Outcomes and risk factors for listing for heart transplantation after the Norwood procedure: An analysis of the Single Ventricle Reconstruction Trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(3):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballweg JA, Dominguez TE, Ravishankar C, et al. A contemporary comparison of the effect of shunt type in hypoplastic left heart syndrome on the hemodynamics and outcome at Fontan completion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(3):537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill GD, Frommelt PC, Stelter J, et al. Impact of initial norwood shunt type on right ventricular deformation: the single ventricle reconstruction trial. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(5):517–521. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohye RG, Sleeper LA, Mahony L, et al. Comparison of shunt types in the Norwood procedure for single-ventricle lesions. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1980–1992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frommelt PC, Guey LT, Minich LL, et al. Does initial shunt type for the Norwood procedure affect echocardiographic measures of cardiac size and function during infancy?: the Single Vventricle Reconstruction trial. Circulation. 2012;125(21):2630–2638. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.072694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohye RG, Schonbeck JV, Eghtesady P, et al. Cause, timing, and location of death in the Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(4):907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon SC, Erickson LK, McFadden M, Miller DV. Effect of ventriculotomy on right-ventricular remodeling in hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a histopathological and echocardiography correlation study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34(2):354–363. doi: 10.1007/s00246-012-0462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frommelt PC, Gerstenberger E, Cnota JF, et al. Impact of initial shunt type on cardiac size and function in children with single right ventricle anomalies before the Fontan procedure: the single ventricle reconstruction extension trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(19):2026–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlo WF, Carberry KE, Heinle JS, et al. Interstage attrition between bidirectional Glenn and Fontan palliation in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(3):511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley SM, Simsic JM, McQuinn TC, Habib DM, Shirali GS, Atz AM. Hemodynamic status after the Norwood procedure: a comparison of right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery connection versus modified Blalock-Taussig shunt. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(3):933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.016. discussion 933-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fogel MA, Rychik J, Vetter J, Donofrio MT, Jacobs M. Effect of volume unloading surgery on coronary flow dynamics in patients with aortic atresia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113(4):718–726. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70229-0. discussion 726-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz SM, 1, Lu M, 2, Ohye RG, 3, Hill KD, 4, Atz AM, 5, Naim MY, 6, Williams IA, 7, Goldberg CS, 8, Lewis A, 9, Pigula F, 10, Manning P, 11, Pizarro C, 12, Chai P, 13, McCandless R, 14, Dunbar-Masterson C, 15, Kaltman JR, 16, Kanter K, 17, Sleeper LA, 2, Schonbeck JV, 2, Ghanayem N, 18 Pediatric Heart Network Investigators. Risk factors for prolonged length of stay after the stage 2 procedure in the single-ventricle reconstruction trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014 Jun;147(6):1791–8. 1798.e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.07.063. Epub 2013 Sep 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell ME, Ittenbach RF, Gaynor JW, Wernovsky G, Nicolson S, Spray TL. Intermediate outcomes after the Fontan procedure in the current era. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131(1):172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu DT, Zak V, Mahony L, Sleeper LA, Atz AM, Levine JC, Barker PC, Ravishankar C, McCrindle BW, Williams RV, Altmann K, Ghanayem NS, Margossian R, Chung WK, Border WL, Pearson GD, Stylianou MP, Mital S Pediatric Heart Network Investigators. Enalapril in infants with single ventricle: results of a multicenter randomized trial. Circulation. 2010 Jul 27;122(4):333–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927988. Epub 2010 Jul 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaddy RE, Boucek MM, Hsu DT, Boucek RJ, Canter CE, Mahony L, Ross RD, Pahl E, Blume ED, Dodd DA, Rosenthal DN, Burr J, LaSalle B, Holubkov R, Lukas MA, Tani LY Pediatric Carvedilol Study Group. Carvedilol for children and adolescents with heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007 Sep 12;298(10):1171–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy S, Bernstein D. The vulnerable right ventricle. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(5):563–568. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almond CS, Thiagarajan RR, Piercey GE, et al. Waiting list mortality among children listed for heart transplantation in the United States. Circulation. 2009;119(5):717–727. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinstein S, Bello R, Pizarro C, et al. The use of the Berlin Heart EXCOR in patients with functional single ventricle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014 Feb;147(2):697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.10.030. discussion 704-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs JP, Quintessenza JA, Boucek RJ, et al. Pediatric cardiac transplantation in children with high panel reactive antibody. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1703–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zangwill S, Ellis T, Stendahl G, Zahn A, Berger S, Tweddell J. Practical application of the virtual crossmatch. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11(6):650–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Everitt MD, Boyle GJ, Schechtman KB, et al. Early survival after heart transplant in young infants is lowest after failed single-ventricle palliation: a multi-institutional study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(5):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pediatric Heart Allocation. [Accessed April 25, 2017]; https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/learn/professional-education/pediatric-heart-allocation.

- 29.Schumacher KR, Almond C, Singh TP, et al. Predicting graft loss by 1 year in pediatric heart transplantation candidates: an analysis of the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study database. Circulation. 2015;131(10):890–898. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Pediatric Heart Failure Registry. [Accessed November 30, 2017]; https://www.ishlt.org/registries/iPHFR.asp.

- 31.Rossano JW, Kim JJ, Decker JA, et al. Prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of heart failure-related hospitalizations in children in the United States: a population-based study. J Card Fail. 2012;18(6):459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.