Abstract

Rationale

While breastfeeding is well recognized as beneficial, rates of breastfeeding among American Indian women are below average and contribute to health inequities. Culturally specific approaches to breastfeeding research are called for to inform appropriate interventions in American Indian communities. Specifically, a grandmother's role in breastfeeding promotion is of great import particularly in American Indian (AI) groups, although is an understudied topic to date.

Objective

This research seeks to fill a prominent literature gap by utilizing a grounded theory and community-based research approach to inform breastfeeding practices from the voices of grandmothers and health care professionals in a rural AI community in the United States.

Methods

A community-based approach guided the research process. Convenience and snowball sampling was used to recruit for semi-structured and follow up member checking interviews with AI grandmothers (n = 27) and health care professionals (n = 7). Qualitative data were transcribed, characterized into meaning units, and coded by a review panel. Data were reconciled for discrepancies among reviewers, organized thematically, and used to generate community-specific breastfeeding constructs.

Results

Three major themes emerged, each with relevant subthemes: (1) importance of breastfeeding; (2) attachment, bonding, and passing on knowledge; and (3) overburdened health care system. Multiple subthemes represent stressors and impact breastfeeding knowledge, translation, and practice within this community including formula beliefs, historical traumas, societal pressures, mistrust, and substance abuse.

Conclusions

Interventions designed to raise breastfeeding rates in the study site community would ideally be grounded in tribal resources and involve a collaborative approach that engages the greater community, grandmothers, health care professionals, and scientific partners with varying skills. More research is needed to determine stressors and any potential impact on infant feeding practices among other AI groups. Application of the research approach presented here to other AI communities may be beneficial for understanding opportunities and challenges to breastfeeding practices.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, American Indian, Infant feeding, Rural health, Qualitative research

1. Introduction

The American Academy of Pediatrics (2012) recommends that breastfeeding occur for the first six months of an infant's life with supplemental feedings continuing to at least one year for optimal health outcomes (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012). Rates of breast-feeding initiation and duration in the United States are highest among non-Hispanic white women with higher socioeconomic status and educational achievement (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). In comparison, American Indian women tend to start and continue breast-feeding less often and for less time (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010).

Breastfeeding promotion efforts are essential for the physical (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011) as well as the mental health of mothers and may enhance maternal-child bonding (Bai et al., 2009; Guttman and Zimmerman, 2000) and decrease the prevalence of postpartum depression (Mancini et al., 2007). Although a prevalent mode of infant feeding, consumption of formula contributes to acute and chronic illnesses not limited to gastrointestinal infection, asthma, childhood obesity, and diabetes mellitus type II (American Academy of Pediatrics (2012); US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), 2011). Methods to increase the likelihood for breastfeeding in American Indian (AI) communities are needed as breastfeeding may be a key component to reducing high obesity rates (Zamora-Kapoor et al., 2017).

However, it is critical for breastfeeding promotions to base in local knowledge and ways of understanding in order to be embraced and successful (Simonds and Christopher, 2013), as is recognized in other AI focused health research (Oré et al., 2016; Goodkind et al., 2015; Fleischacker, 2016; Wilhelm et al., 2012). For example, AI grandmothers are deemed central to instilling life skills and providing a link to cultural background for younger generations within many tribal groups (Kincheloe and Kincheloe, 1983; Byers, 2010; Robbins et al., 2005). This includes acting as breastfeeding advocates to influence infant feeding practices (Wright et al., 1997). AI grandmothers (with respect to the child), in addition to an AI mother's sisters and/or in-laws, are often found to act as primary consults in infant feeding decisions, rather than public health institutions and medical professionals (Eckhardt et al., 2014). Globally the influential power of grandmothers specific to breastfeeding has been an important investigative area, though remains understudied in the United States (US) (Negin et al., 2016) despite public health agencies noting the value (HHS, 2011).

Generally little breastfeeding literature specific to AI populations is available (Eckhardt et al., 2014; Dodgson et al., 2002; Horodynski et al., 2011; Rhodes et al., 2008; Wilhelm et al., 2012; Wright et al., 1997), and to the authors' knowledge, no studies have primarily focused on AI grandmother perceptions with regard to breastfeeding. For the Ojibwe, society, community, family (particularly elders), and culture were found to impact breastfeeding practices (Dodgson et al., 2002). Further evidence suggests that strengthening familial and cultural ties to the tradition of breastfeeding may facilitate increased rates (Rhodes et al., 2008) and has been a successful approach within Navajo populations (Wright et al., 1997). Last, the importance of female family member involvement during infant feeding education and promotions is notable (Horodynski et al., 2011).

Tribal nations have diverse customs and beliefs that limit the ability to generalize breastfeeding experiences amongst diverse AI populations. As such, this presented research fills large literature gaps by crucially adding AI grandmother perspectives to the current body of science in order to inform the potential for breastfeeding interventions in an understudied AI community. A community-specific and qualitative approach to research using constructs of Community Based Participatory Research (Israel et al., 1998) was pursued to elicit breastfeeding practice perceptions from AI grandmothers and community health care professionals on the Fort Peck Reservation in rural Montana.

2. Method

This research focused on collecting breastfeeding perceptions foremost from grandmothers and then from community healthcare professionals, based upon direction from the community and confirmation in the literature (Eckhardt et al., 2014; HHS, 2011; Wright et al., 1997). Community stakeholders perceived elders as less promotional of breastfeeding currently than in the past and mothers as more apt to follow health care advice from family members rather than health care professionals.

Given a lack of supporting information on this topic to date (Creswell, 2014), qualitative interviews, in addition to a grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, 1990) and a community-based approach (Israel et al., 1998) to the research were appropriate. Thus, researchers could adhere to a cultural tradition of oral storytelling (Gray et al., 2010). Grounded theory generates knowledge based on data resulting from repeated social interactions (Corbin and Strauss, 1990) and was applied to conceptualize breastfeeding practices from the voices of AI grandmothers and health care professionals.

A community-based research approach utilizing Community Based Participatory Research constructs complemented this methodological approach and balanced community needs as summarized by Israel et al. (Israel et al., 1998). The application of culturally appropriate methodologies, such as Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) (Israel et al., 1998), is increasingly important to tribal research partnerships (Christopher et al., 2011). A key component of CBPR specific to AI populations is for investigators to remain cognizant of undesirable community research practices over time that have contributed to historical traumas (Christopher et al., 2011; Simonds and Christopher, 2013). CBPR includes key stakeholders and community members in each research process (Israel et al., 1998). It is preferred as a process because it strives to build trust, community capacity, and integrate culturally specific knowledge into the research agenda (Simonds and Christopher, 2013). Therefore, constructs of CBPR were applied to all stages of the research though realities such as limited funding, multiple responsibilities of target community stakeholders, and timing constraints disallowed for a true CBPR approach. A lack of a non-changing sample of community stakeholders continuously engaged throughout the research lifespan remains this presented work's main deviation from CBPR methodology.

2.1. Study setting

Montana is predominately a rural, frontier state (US Department of Agriculture, 2015) with a high census of non-Hispanic white (89.2%) and AI (6.3%) residents (US Census Bureau, 2015). This research took place on the Fort Peck Reservation in northeastern Montana, a high prairie, rural frontier community spanning more than two million acres, 50 miles south of Canada and directly north of the Missouri River (Fort Peck Tribes, n.d.).

Around 6,000 enrolled members reside in the Fort Peck community, comprising of divisions of the Sioux and Assiniboine Nations (Fort Peck Tribes, n.d..), along with other AI groups from neighboring and non-neighboring tribes. The Assiniboine Bands represented include Wadopana and Hudashana, meaning ‘Canoe Paddlers Who Live on the Prairie’ and ‘Red Bottom,’ respectively. The Sioux Bands represented include the Sisseton, Wahpeton, Yanktonais, and the Teton Hunkpapa (Miller et al., 2012).

2.2. Role of researchers

All researchers involved are non-native, outside researchers and have experiential differences with the target community and indigenous populations. Interactions over multiple visits with the target community can best be described as a consulting relationship (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2010), where researcher and first author (BH) primarily initiated data collection and community-based interpretational feedback. Co-authors (CBS, SA, ER) provided input and guidance specific to the research process and contributed to the study each in various ways with respect to their expertise.

2.3. Ethics

Research presented was approved by the Fort Peck and Montana State University institutional review boards for research conducted with human subjects. The Fort Peck institutional review board approved this manuscript prior to submission.

2.4. Sampling and recruitment

2.4.1. Grandmothers

Grandmothers with a grandchild, self-identifying as a member of a federally recognized tribe, and living on the Fort Peck Reservation were recruited for interviews via convenience and snowball sampling (Creswell, 2014). The primary focus of the research was explained as learning more about breastfeeding practices from grandmothers. In total, 27 grandmothers were recruited for interviews, and five potential participants declined participation due to a stated lack of interest. Compensation for complete participation was valued at approximately $50.

2.4.2. Health care professionals

Health care participants were employed at Indian Health Services (HIS) (n = 4), Tribal Health (n = 1), and Northeast Montana Health Services (n = 2). Participant expertise was in the following areas: Registered Nurse, public health (n = 4); Registered Nurse, labor and delivery (n = 2); and WIC Registered Dietitian (n = 1). In total, three participants stated certification as a lactation consultant. Six participants identified as non-native and one self-identified as an enrolled member of a federally recognized tribe in another state.

2.5. Data collection

The interviewer (BH) was trained by qualitative experts in the field (CBS, SA, ER). The overall interviewer intent was to listen, not interrupt speech or thought processes, and facilitate appropriate questions. Participant informed consent was obtained and all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Semi-structured and follow-up member checking interviews were recorded between December 2015 and April 2016. Interview questions were developed from initial community consultations to identify breastfeeding topics important to community stakeholders and changed slightly between grandmother and health care professional participant populations (see supplementary file). During the follow-up member checking interviews, each participant reviewed individual typed transcripts, shared further information or added clarification, and provided guidance and insight regarding researchers' perceived study outcomes or themes.

2.6. Data analysis

Analysis of qualitative data was iterative as required by grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, 1990), and the organization of transcribed data was based on the constant comparison method (Lichtman, 2013). All interviews were de-identified and split into meaning units by the first author (BH). Next, coauthors (CBS, SA, ER) double-coded transcripts with the first author (BH) and discrepancies were resolved as a team to minimize potential bias. Thereafter, coded meaning units derived from the data were organized into broad themes and subthemes with contributions from authors, tribal stakeholders, and research participants. It was clear to researchers that data saturation occurred during the first round of interviews because no new information emerged during member checking interviews.

Generation of the community-level breastfeeding constructs was accomplished through multiple engagements between researchers and community stakeholders, including health care professionals (participant and non-participant), participant grandmothers, and community members with interest in the research. This continual feedback and engagement with the community to finalize emergent data concepts is a core component of grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, 1990). Conceptualization resulted from discussions of researcher observations and feedback from member checking interviews in addition to the salient themes derived from the data, experiential time spent in the field, and expert review. Perceived construct conceptualization was confirmed during a final member checking process that engaged a smaller sample of participant grandmothers with leadership roles within the community in addition to health care professional stakeholders.

3. Results

All meaning units (n = 1,713) from the 27 grandmother and seven health care professional interviews were organized thematically with frequencies by theme/subtheme constructs reported to display the number of contributors (Table 1). Primary interviews ranged from 13 to 119 minutes (mean = 66), and member checking interviews ranged from 13 to 126 minutes (mean = 69.5). The follow-up rate for member checking interviews was 81.8%; one participant was uninterested in following up, four were unable to be contacted, and one had passed away. One participant was added to the study sample at the time of secondary interviews and therefore was not pursued for a follow-up.

Table 1.

Qualitative theme and subtheme frequenciesa for interviews with participant grandmothers (n = 27) and health care professionals (n = 7) in an AI community.

| Themes | Participant Grandmothers | Participant Health Care Professionals | Subthemes | Participant Grandmothers | Participant Health Care Professionals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment, Bonding, & Passing on Knowledge | 26 (175) | 7 (21) | |||

| Gender | 25 (58) | 1 (1) | |||

| Historical Trauma | 16 (45) | 3 (3) | |||

| Language | 14 (15) | 0 (0) | |||

| Plants and Foods | 26 (53) | 7 (15) | |||

| Social Norms | 21 (64) | 7 (16) | |||

| Substance Abuse | 24 (95) | 7 (26) | |||

| Importance of Breastfeeding | 27 (176) | 6 (21) | Formula Beliefs | 27 (148) | 5 (11) |

| Overburdened Health Care System | 26 (114) | 7 (98) | Mistrust | 15 (20) | 5 (11) |

Note.

The number of participants contributing to each theme is displayed along with total supporting meaning units (parenthesis).

3.1. Demographics

3.1.1. Grandmothers

Age of participant grandmothers ranged from 38 to 87 years (mean = 62.5). A majority of participants identified as married (62%), were employed (70%) (full or part time), reported financial security (70%) (see supplementary file), and attended college (78%). Tribal affiliations were self-reported as: Sioux (n = 15), Lakota Sioux (n = 1), Assiniboine (n = 14), Gros Ventre (n = 1), Fort Peck (n = 4), Chippewa (n = 4), Cheyenne Arapaho (n = 1), Dakota (n = 1), and Cherokee (n = 1). Often participants identified with more than one tribe (n = 11). On average, each participant had between three and four children. The majority (78%) stated breastfeeding at some point, with 52% continuing to six months, and 44% to at least one year. Many (52%) reported participation in the US Department of Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) at one time.

3.1.2. Health care professionals

Health care participants were employed at Indian Health Services (IHS) (n = 4), Tribal Health (n = 1), and Northeast Montana Health Services (n = 2). Participant expertise was in the following areas: Registered Nurse, public health (n = 4); Registered Nurse, labor and delivery (n = 2); and Special Supplemental Program for WIC Registered Dietitian (n = 1). In total, three participants stated certification as a lactation consultant. Six participants identified as non-native and one self-identified as an enrolled member of a federally recognized tribe in another state.

3.2. Theme and subtheme results

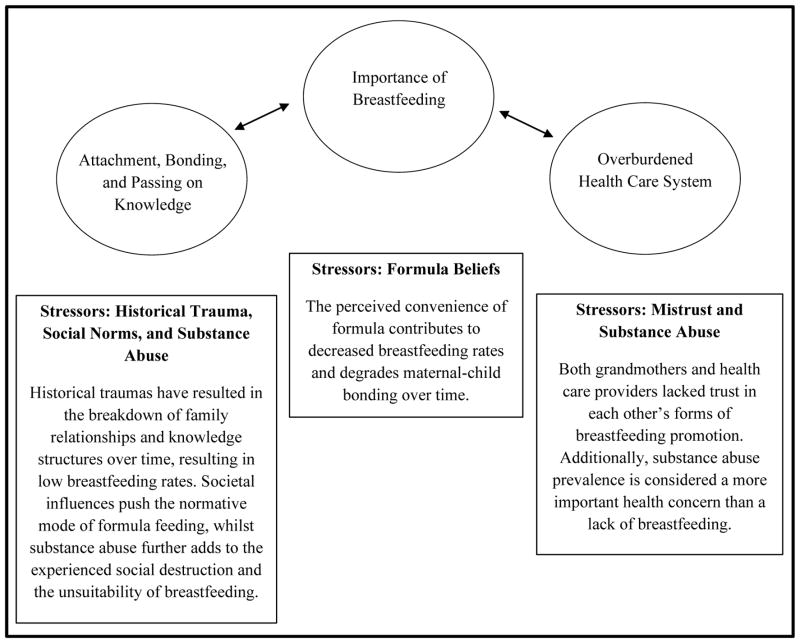

This research generated three themes and eight subthemes to describe breastfeeding practices (Table 1). The grounded theory-based conceptualization (Fig. 1) represents the interrelation of major construct themes (Importance of Breastfeeding; Attachment, Bonding, & Passing on Knowledge; and Overburdened Health Care System) and subthemes (Gender; Historical Trauma; Language; Plants and Foods; Social Norms; Substance Abuse; Formula Beliefs; Mistrust). For example, the major study themes represent community realities and bodies of knowledge integral to the breastfeeding process within this AI community, whereas select study subthemes often represent barriers or ‘stressors’ that mitigate opportunities to breastfeed. While not identified as ‘stressors,’ the subthemes of Gender, Language, and Plants and Foods were impacted by such.

Fig. 1.

The role that stressors play on emergent themes based on qualitative interviews with participant grandmothers and health care professionals in an AI community.

Presented below is supporting information regarding each of the three major themes that emerged from the qualitative interviews. The text refers to multiple figures that provide participant quotes in description of the research results and infer the relationship between themes and subthemes from participant voices. Fig. 1 provides a conceptual representation of these relationships.

Theme 1: Importance of Breastfeeding

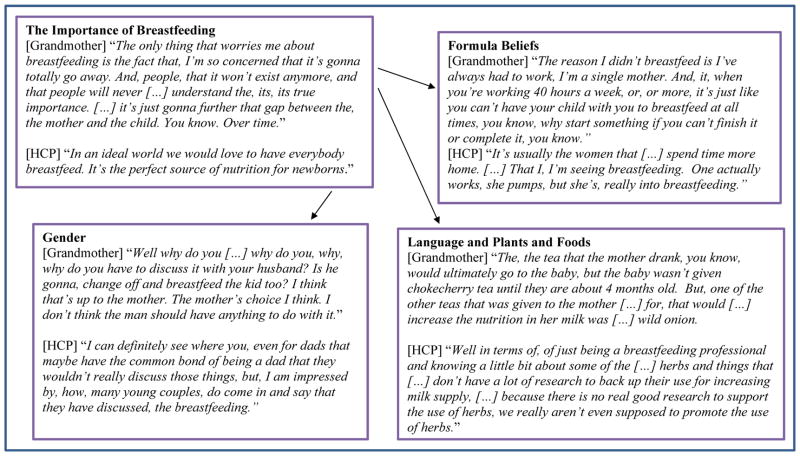

Despite the noted lack of breastfeeding practice or discussion mentioned by study participants within this community, the act of breastfeeding is highly esteemed. Health care professionals shared their immense knowledge of breast-feeding benefits and the desire to increase breastfeeding rates within the community. All of the grandmothers, except one, were knowledgeable about breastfeeding benefits and reported promoting breast-feeding. Maternal-child bonding was described as one of the most beneficial outcomes of breastfeeding initiation and duration. A lack of breastfeeding was at times described as a component disconnecting current familial relationships or was suggested as a way to promote healthy maternal-infant pairs via bonding (See Fig. 2.).

Fig. 2.

Thematic importance of breastfeeding and sub-thematic quotes from breastfeeding interviews with AI grandmothers and community health care professionals (HCP).

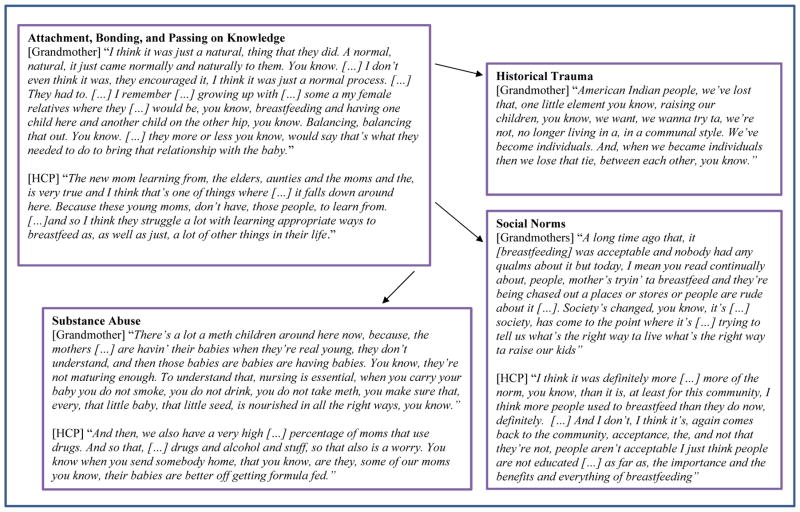

Theme 2: Attachment, Bonding, and Passing on Knowledge

The attachment and bonding process between a mother and infant is perceived to be strengthened through breastfeeding. Additionally, the sharing or passing along of breastfeeding knowledge within family and community structures was described as a critical component to a healthy maternal-child breastfeeding relationship - elements of which are often in decline or absent in modern society.

Changing family structures over time—which are partially a result of select subtheme stressors (Fig. 1)—have impacted if and how much breastfeeding knowledge is shared with a mother. Family support for breastfeeding seemed to impact a mother's ability or desire to breast-feed and consequently the overall attaching and bonding with the infant (See Fig. 3.).

Fig. 3.

Thematic attachment, bonding, and passing on knowledge and sub-thematic quotes from breastfeeding interviews with AI grandmothers and community health care professionals (HCP).

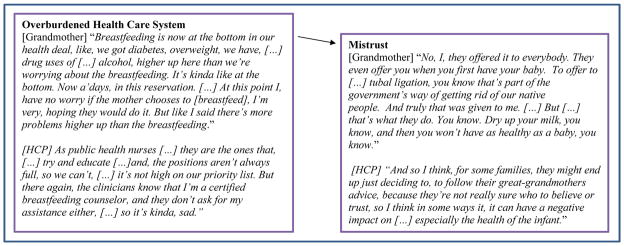

Theme 3: Overburdened Health Care System

This theme describes a large barrier to maternal and child health in the community generally and also to breastfeeding support and promotion specifically. Although females within the family structure were described as the primary source of breastfeeding support and information, many grandmothers referred to the community health care system as a secondary and important means of acquiring knowledge. However, a lack of resources within the community health care system specific to maternal and child health and breastfeeding was often mentioned.

A lack of health care infrastructure coupled with multiple system stressors (Fig. 1) results in little to no breastfeeding promotion from providers. For example, breastfeeding education is considered critical before the infant is born but little prenatal contact is available within the community health care network. Further, a lack of health care personnel was noted, resulting in individuals covering multiple health care responsibilities (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Thematic overburdened health care system and sub-thematic quotations from breastfeeding interviews with AI grandmothers and community health care professionals (HCP).

Subtheme 1.1: Formula beliefs

Formula beliefs are a stressor to Theme 1 (Fig. 1) and inhibit breastfeeding practices as the use of formulas was described as the normative mode of infant feeding by all participants. For example, one participant stated, “I don't even think I know any young girls that have, I've ever seen breastfeeding.” Many participants noted the convenience of formula feeding as the primary appeal, “For bottle feeding, it's convenience, and we're a society that looks for convenience all the time.” Prominently, being a stay at home mother seemed to accommodate the breastfeeding process more so than a mom trying to balance work and breastfeeding (Fig. 2).

Despite the convenience attributed to the prevalence of formula feeding, grandmothers often provided conflicting examples highlighting resource and time barriers to formula feeding: “The number one, number one is cost. Number two, I think is keeping the supplies, and number three I feel it's cleanliness. Maintaining an environment clean enough.” Further, the inconvenience of breastfeeding was often described as a maternal time investment necessary for maternal and child bonding: “That would probably have to be the convenience of a, bottle fed baby, rather than […] the intimate, sitting down, attachment to the child. The bottle-fed baby, I don't think […] the attachment is as strong, because people can just put the bottle in the baby's mouth, and prop it up and walk away and do what they have to do.”

WIC supplementation of infant formula was a topic mentioned quite often among participant grandmothers. A shortage of supplies as infant formulas fell short of providing complete infant nutrition each month was described as a challenge. No grandmother believed that infant formula was affordable within the community despite many purchasing infant formulas in order to support family or community member needs. For example, an AI grandmother describes this phenomenon: “It's just a supplement and a lot of the programs out there supplement. But there's never enough […] to […] feed a baby for a full month, and I know that, because I, as a grandma I have bought, cans and cans of, […] milk. […] If you don't have actual, […] somebody to support and help you, you know, yeah, children will go without. And we do have that, that does happen in our community a lot.”

Subtheme 2.1: Gender

Within this community female family members are responsible for discussing and teaching about maternal and child health topics including breastfeeding, relevant to Theme 2. The majority did not consider males to have an acceptable place in this discussion, although this seemed normal to a minority of participants who described the increasing role of the male partner in the decision to breastfeed (Fig. 2). It seems possible that stressors have impacted gender roles within the community (Fig. 1), as some women spoke of lessoned familial support from males in general external to breast-feeding support.

Subtheme 2.2 and 2.3: Language and Plants and Foods

Cultural knowledge regarding language, plants, and foods that contribute to the breastfeeding experience were known in detail by only a few. This adds context to Theme 2. Many spoke of the language around breastfeeding or applications of specific plants and foods to promote breastfeeding as knowledge once known by their grandmother and not passed along within the family structure: “That's another thing too, my, my mom, my dad, my grandma they all, talked Indian to each other, but they never taught it to us.” This subtheme is not considered a stressor; however it is a portion of knowledge that has been affected by negative community experiences (Fig. 1). Further, health care professionals generally spoke of these topics only within the context of their professional training background or personal experiences (see Fig. 2).

Subtheme 2.4 and 2.5 and 2.6: Historical Trauma, Substance Abuse, and Social Norms

Historical trauma, substance abuse, and social norms are main stressors experienced within the community that are responsible for altering culturally specific social processes over time (Fig. 1). These stressors ultimately impact attachment, bonding, and passing on knowledge that are necessary to promote breastfeeding practices and often overshadow the perceived importance of breast-feeding initiatives within the community.

Historical trauma, characterized by various cultural oppressions over time, is described as a long-standing stressor within this community and many AI communities (Whitbeck et al., 2004). It has contributed to a lack of knowledge translation between generations within many AI familial units, such as the aforementioned subthemes of language, and plants and foods specific to breastfeeding (Fig. 3). Additionally, a high concern of substance abuse inhibits widespread breastfeeding practices within this community. Most every grandmother and all health care professionals commented on the perceived use of illicit substances or provided examples of how families and the greater community have been impacted by this reality. Changing social norms in the wider community also minimizes the acceptability of breastfeeding practices. Breastfeeding was often described as a past social norm or value in the community. For example, many participants told stories of widespread availability of breastfeeding assistance or support within the community and examples of how these practices are less commonplace today, impacting perceptions and the likelihood of a mother to breastfeed (See Fig. 3).

Subtheme 3.1: Mistrust

Another stressor to breastfeeding promotion and support in the community was an emergent sense of mistrust between grandmother and health care professional populations (Fig. 1). Prior negative personal experiences with the health care system seemed to translate into current mistrust of modern medical practices by many grandmothers. This was established most often by grandmothers who at times shared personal stories of receiving medical shots from health care personnel to dry up milk supply; however, many grandmothers and health care professionals were unaware of this reality when the topic was broached during the member checking process (Fig. 4).

Health care professionals expressed mistrust most often in describing a clientele uninterested in provided health care services. The providers often described missed appointments with a lack of rescheduling and the perception that many in the community view general health care as “not a priority.” With respect to community breast-feeding promotion and support, this disconnect is inhibitive to any progress. Also, many times the recommendations of health care professionals were described as secondary to family members' advice, resulting in possible misinformation (Fig. 4).

4. Discussion

This research aimed to conceptualize breastfeeding perceptions and practices as described by tribal grandmothers and the community health care network using a community and grounded theory-based research approach. Results indicate breastfeeding is a highly-regarded—though rarely occurring—practice, as described by all participants. A lack of attachment, bonding, and the passing on of knowledge coupled with an overburdened healthcare system has resulted in decreased breastfeeding rates, despite the perceived importance of breastfeeding. Emergent subthemes or stressors that impact multiple sectors as outlined in Fig. 1 are considered to be inhibitive to breast-feeding relationships and practices. This reality does not widely differ from other research identifying risk factors among AIs that contribute to concerning health disparities (Burnette and Figley, 2016) or from research on the impact of colonization or historical traumas on health outcomes apparent in many AI communities (Burnette and Figley, 2016; Whitbeck et al., 2004).

The populations explored within this research have not yet been a primary focus in AI breastfeeding literature to date. Sectors that are found to be critical for informing optimal infant feeding practices (i.e., family, community, and culture) within this research are similarly detailed in other AI breastfeeding research (Dodgson et al., 2002; Rhodes et al., 2008; Wright et al., 1997). This work indicates that grandmothers have an essential role in the integration of family, culture, and breastfeeding advocacy. Future breastfeeding interventions need utilize AI grandmother knowledge and support and test the effect on breastfeeding perceptions and likelihood as well as on breastfeeding initiation and duration rates.

To the authors' knowledge, only one other study has included health care professionals', alongside AI participants', perceptions specific to infant feeding practices (Horodynski et al., 2011). The research results presented indicate a shared perception of mistrust and mis-communication between the two populations and note the importance of available family knowledge and support for optimal infant feeding practices, including breastfeeding (Horodynski et al., 2011). Further, a recent review of WIC breastfeeding literature synthesized promising breastfeeding strategies at the individual, social, environmental, and policy levels and found health care provider support as one vital factor in enhancing the likelihood of WIC participants to breastfeed (Houghtaling et al., 2017). Ultimately, research and interventions seeking to engage both populations and build trust in order to overcome documented stressors would be of value within this community.

This research captures a reality of grandmothers bearing the responsibility of purchasing formulas to cover periods of the month that are not covered by WIC supplementation in this community. The WIC packages include food and formula resources based on the package choice of full, partial, or no breastfeeding (US Department of Agriculture, 2014). The full breastfeeding choice is inclusive of a greater multitude of food offerings for the mother and less formula issuance overall (US Department of Agriculture, 2014), and it is important to note that a review suggests that package partitions alone do not influence the infant feeding decision (Schultz et al., 2015). WIC is a supplemental program meaning that issued formula is not designed to provide complete infant nutrition for an entire month (US Department of Agriculture, 2014). However, the high purchase price of formulas and the supplemental nature of the WIC program negatively impact infant feeding practices within this AI community, which suggests that infants may not meet nutrient needs or that community members without infants are contributing large portions of their incomes to support others' nutrient needs.

To further understand these findings, study authors developed a tool, InFeed, to measure availability and affordability of infant feeding resources throughout communities (Houghtaling et al., unpublished results). Notable price variations were documented in WIC-accepted formula brands, at times differing by about six dollars based on store location, with the most expensive formula priced at nearly 22 dollars per 12.4 ounces (Houghtaling et al., unpublished results). Future qualitative infant feeding research should include quantitative measures, such as the InFeed, in describing opportunities and barriers regarding infant food security in low access AI communities, as this qualitative data provides rich context to extreme formula costs documented. Such results can add more comprehensive information to the literature in order to formulate effective interventions that may ultimately influence WIC policy.

Research results also uncover variables inhibitory to breastfeeding (stressors) not regularly reported within the context of infant feeding or breastfeeding research to date. For example, substance abuse was described as a major stressor prohibitive to breastfeeding and health care support within this study. This concern is not unique to this community or AI communities in general, as the use of illicit substances is increasing nationwide (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015). Addiction or substance abuse is considered the most undertreated neurologic disease in America (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2012), with rates of maternal opioid use more pronounced in rural areas (Villapiano et al., 2017). Prevalence of substance abuse and the potential effect on interpersonal relationships should not be ignored in any nutrition research moving forward, relevant to breastfeeding. Further, breastfeeding may be a critical component of substance abuse interventions (MacVicar et al., 2017). Addressing these sensitive barriers in future research will assist in providing more in-depth knowledge of breastfeeding barriers that are needed (Houghtaling et al., 2017) to design successful and meaningful breastfeeding interventions to support vulnerable populations.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This research involved stakeholders grounded in the community from project inception to dissemination. Concepts derived from qualitative findings describe opportunities and barriers for breastfeeding support in addition to a strong regard for the act of breastfeeding in this community. The descriptive and in-depth qualitative findings are integral to the design of culturally appropriate interventions in this study setting. The process and study results of this research provide a framework to be applied to other AI communities for those aiming to conceptualize community specific breastfeeding practices in order to build upon strengths and overcome challenges to breastfeeding promotion.

A limitation of this research is a possible sample bias attributed to sampling techniques. Grandmothers and health care professionals with strong feelings of breastfeeding practices may have been more prone to participating. Qualitative methods, though appropriate for this research, limit generalizability of study findings to other AI groups. Breastfeeding science warrants the development of quantitative tools that might be applied to a variety of diverse populations to be used alongside qualitative modes of expression. The constructs identified within this research call for additional testing in order to determine if interventions specific to one area, such as grandmother-health care provider trust building, impact breastfeeding rates as the conceptualization indicates interconnectedness. Likewise, work to minimize construct stressors identified within this work warrant future research to determine if there is a resulting impact on breastfeeding rates. Finally, gaining perspective related to infant feeding practices from the younger AI community, including sexually active teens and new mothers, is a necessary next step for a more holistic picture of challenges and opportunities to breastfeed in this community.

5. Conclusions

Interventions designed to raise breastfeeding rates in this AI community would ideally be grounded in tribal resources due to the considerable burden on the existing health care structure. Interventions that engage both grandmothers and health care professionals to support and facilitate relationship building and breastfeeding support whilst minimizing identified stressors are needed. Collaborative approaches to research and intervention design alongside strong AI community stakeholders using research agendas grounded in CBPR processes along with diverse scientist skill sets (as breastfeeding barriers extend beyond nutrition science) are appropriate. Application of these research techniques to other communities may be beneficial for understanding how opportunities and barriers to breastfeeding are similar or different in order to add further context to the literature specific to AI breastfeeding practices. Last, understanding how uncovered stressors such as substance abuse and trauma affect breastfeeding rates in AI communities nationwide is critical as current breastfeeding literature lacks such analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors received funding support for the study presented here from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM103474 and Award Number 5P20GM104417.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.017.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest in regard to funding sources and the conclusions drawn from this article.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. Available at. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai YK, Middlestadt SE, Joanne Peng CY, Fly AD. Psychosocial factors underlying the Mother's decision to continue exclusive breastfeeding for 6 Months: an elicitation study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009;22(2):134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, Figley CR. Risk and protective factors related to the wellness of american indian and Alaska native youth: a systematic review. Int Public Health J. 2016;8(2):137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Byers L. Native american grandmothers- cultural tradition and contemporary necessity. J Ethnic Cult Divers Soc Work. 2010;19(4):305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state - national immunization survey, United States, 2004–2008. MMWR. 2010;59(11):327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S, Saha R, Lachapelle P, Jennings D, Colclough Y, Cooper C, Cummins C, Eggers MJ, FourStar K, Harris K, Kuntz SW, LaFromboise V, LaVeaux D, McDonald T, Bird JR, Rink E, Webster L. Applying indigenous community-based participatory research principles to partnership development in health disparities research. Fam Community Health. 2011;34(3):246–255. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318219606f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research Design. 4. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson JE, Duckett L, Garwick A, Graham BL. An ecological perspective of breastfeeding in an indigenous community. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(3):235–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CL, Lutz T, Karanja N, Jobe JB, Maupomé G, Ritenbaugh C. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs that can influence infant feeding practices in american indian mothers. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(1):1587–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischacker S. Emerging opportunities for registered dietitian nutritionists to help raise a healthier generation of native american youth. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(2):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort Peck Tribes. [Accessed February 25, 2017];Fort Peck Assiniboine & Sioux tribal history. n.d Available from http://www.fortpecktribes.org/tribal_history.html.

- Goodkind JR, Gorman B, Hess JM, Parker DP, Hough RL. Reconsidering culturally competent approaches to american indian healing and well-being. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(4):486–499. doi: 10.1177/1049732314551056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray N, Oré de Boehm C, Farnsworth A, Wolf D. Integration of creative expression into community-based participatory research and health promotion with native americans. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(3):186–192. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181e4bbc6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman N, Zimmerman DR. Low-income mothers' views on breastfeeding. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(10):1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horodynski MA, Calcatera M, Carpenter C. Infant feeding practices: Perceptions of native american mothers and health paraprofessionals. Health Educ J. 2011;71(3):327–339. [Google Scholar]

- Houghtaling B, Byker Shanks C, Ahmed S, Smith T. Resources lack as food environments become more rural: Development and implementation of an infant feeding resource survey. Under Review. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2019.1613275. Unpublished Results. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghtaling B, Byker Shanks C, Jenkins M. Likelihood of breastfeeding within the USDA's food and nutrition Service special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children (WIC) population: a systematic review of literature. J Hum Lactation. 2017;33(1):83–97. doi: 10.1177/0890334416679619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Publ Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe JL, Kincheloe TS. The cultural link: Sioux grandmothers as educators. JSTOR. 1983;57(3):135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman M. Qualitative Research in Education: a User's Guide. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2013. Making meaning from your data. [Google Scholar]

- MacVicar S, Humphrey T, Forbes-McKay KE. Breastfeeding support and opiate dependence: a think aloud study. Midwifery. 2017;50:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini F, Carlson C, Albers L. Use of the postpartum depression screening scale in a collaborative obstetric practice. J Midwifery Wom Health. 2007;52(5):429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Smith D, McGeshik J, Shanley J, Sheilds C. The History of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, 1600–2012. Fort Peck Community College; Poplar, MT: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based Participatory Research for Health: from Process to Outcomes. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2010. Are academics Irrelevant? Approaches and roles for scholars in CBPR. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Addiction Medicine: Closing the Gap between Science and Practice. Columbia University; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Accessed date: 1 October 2016];Drug Facts, Nationwide Trends [online] 2015 Available at. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends.

- Negin J, Coffman J, Vizintin P, Raynes-Geenow C. The influence of grandmothers on breastfeeding rates: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(91) doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0880-5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0880-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oré CE, Teufel-Shone NI, Chico-Jarillo TM. American indian and Alaska native resilience along the life course and across generations: a literature review. Am Indian Alaska Native Ment Health Res. 2016;23:134–157. doi: 10.5820/aian.2303.2016.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KL, Hellerstedt WL, Davey CS, Pirie PL, Daly KA. American indian breastfeeding attitudes and practices in Minnesota. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(1):46–54. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0310-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins R, Scherman A, Holeman H, Wilson J. Roles of american indian grandparents in times of cultural crisis. J Cult Divers. 2005;12(2):62–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz DJ, Byker Shanks C, Houghtaling B. The impact of the 2009 special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children food package revisions on participants: a systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(11):1832–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.06.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds VW, Christopher S. Adapting western research methods to indigenous ways of knowing. Am J Publ Health. 2013;103(12):2185–2192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. [Accessed date: 25 February 2017];QuickFacts Montana. 2015 Available from. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/30.

- US Department of Agriculture. [Accessed date: 25 February 2017];Frontier and Remote Area Codes. 2015 Available from. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/frontier-and-remote-area-codes/

- US Department of Agriculture. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC Food Packages (Final Rule) Food and Nutrition Service; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Office of the Surgeon General; Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Villapiano NLG, Winkelman TNA, Kozhimannil KB, Davis MM, Patrick SW. Rural and urban differences in neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid use, 2004 to 2013. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):194–196. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among american indian people. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(3–4):119–130. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027000.77357.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Rodehorst-Weber K, Aguirre T, Stepans MB, Hertzog M, Clarke M, Herboldsheimer A. Lessons learned conducting breastfeeding intervention research in two northern plains tribal communities. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(3):167–172. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AL, Naylor A, Wester R, Bauer M, Sutcliffe E. Using cultural knowledge in health promotion: breastfeeding among the Navajo. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(5):625–639. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Kapoor A, Omidpanah A, Nelson LA, Kuo AA, Harris R, Dedra S, Buchwald DS. Breastfeeding in infancy is associated with body mass index in adolescence: a retrospective cohort study comparing american Indians/Alaska natives and non-hispanic whites. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(7):1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.