Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infections cause congenital birth defects and disease in immunosuppressed individuals. Antiviral compounds can control infection yet their use is restricted due to concerns of toxicity and the emergence of drug resistant strains. We have evaluated the impact of an RNA Polymerase I (Pol I) inhibitor, CX-5461 on HCMV replication. CX-5461 inhibits Pol I-mediated ribosomal DNA transcription by binding G-quadruplex DNA structures and also activates cellular stress response pathways. The addition of CX-5461 at both early and late stages of the HCMV infection inhibited viral DNA synthesis and virus production. Interestingly, adding CX-5461 after the onset of viral DNA synthesis resulted in a greater reduction compared to continuous treatment starting early during infection. We observed an accompanying increase in cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in infected cells treated late but not early which likely explains the differences. Our previous studies demonstrated the importance of p21 in the antiviral activity of the HCMV kinase inhibitor, maribavir. Addition of CX-5461 increased the anti-HCMV activity of maribavir. Our data demonstrate that CX-5461 inhibits HCMV replication and synergizes with maribavir to disrupt infection.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, CX-5461, RNA Polymerase I, G-Quadraplexes, maribavir, Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor p21

1. Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a member of the beta-herpesvirus family and infects a majority of the world population (Mocarski et al., 2013). Infection is usually asymptomatic in healthy adults and children but can cause serious disease in immunocompromised individuals. HCMV is also the leading viral cause of birth defects following infection in utero (Britt, 2017). The introduction of ganciclovir over two decades ago has significantly improved the management of HCMV disease. However, due to continued concerns of toxicity, poor oral bioavailability and the emergence of drug resistant strains, interests remain high to develop vaccines and alternative therapeutic strategies (Anderholm et al., 2016; Hakki and Chou, 2011). Two antiviral compounds more recently introduced are letermovir, inhibiting the HCMV terminase (Goldner et al., 2011; Lischka et al., 2010) and maribavir, inhibiting the HCMV kinase (Baek et al., 2002; Biron et al., 2002). Studies have also implicated the cellular nucleolar stress response pathway as a possible target for antiviral compound development (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2016). This stress response pathway is activated following insults to the cell including DNA damage and disruption of ribosome homeostasis (James et al., 2014).

Disrupting ribosome homeostasis results in the induction of a p53-dependent nucleolar stress response (James et al., 2014). This response is induced by the compound, CX-5461 which disrupts RNA Polymerase I (Pol I)-mediated transcription (Drygin et al., 2011). Recently, CX-5461 was determined to act by binding to and stabilizing G-quadruplex DNA structures (Xu et al., 2017). G-quadraplexes are naturally formed in guanine-rich sequences consisting of four-stranded helical structures. CX-5461 selectively inhibits some cancers by sensitizing cells to DNA damage responses and is currently being evaluated for treating solid tumors (Quin et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017).

In these studies, we have investigated the impact of the Pol I inhibitor and G-quadruplex binding compound, CX-5461 on HCMV replication.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Cell culture and viral stocks

MRC-5 fibroblasts (ATCC) were propagated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were grown to 70% confluence and serum-starved using 0.5% FBS for 24 h to synchronize the population prior to experiments. The HCMV strain AD169 (ADwt) and strain TB40/E (TBwt) were produced from the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones (Murphy et al., 2003; Sinzger et al., 2008). Viral stocks were obtained from culture medium and pelleted through a sorbitol cushion (20% sorbitol, 50 mM Tris-HCL pH 7.2, 1 mM MgCl2) at 55,000 × g for 1 h in a Sorvall WX-90 ultracentrifuge and SureSpin 630 rotor (ThermoFisher Scientific). Stocks were titered using a limiting dilution assay (TCID50) using MRC-5 cells in 96-well dishes and detecting HCMV IE1-positive cells at 2 weeks post infection. Infections were completed using a multiplicity of 3 IU/cell and virus removed after 2 hpi. In drug treatment experiments, compounds were added at 2 or 48 hpi and replaced every 24 h. Cells were treated with 500 nM or indicated concentration of CX-5461 (Selleck Chemicals), 0.01 to 10 μM maribavir (MBV) (Shire) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a vehicle control. Titers from experimental samples were determined by plating serial dilutions of cell supernatants on MRC-5 cells in 12-well dishes, washing after 2 hpi, staining at 48 hpi with an anti-IE1 antibody, and counting IE1-postive cells. CX-5461 toxicity was determined by treating MRC-5 cells with increasing concentrations of CX-5461 from 50 nM to 10 μM and counting Trypan Blue-positive cells after 48 hr (ThermoFisher Scientific).

2.2 Analysis of protein and nucleic acid

Steady state protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) containing protease inhibitors (Roche) and lysed by sonication. Protein samples were then resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate - 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a Protran nitrocellulose membrane (Sigma-Aldrich) by semidry transfer. The membrane was blocked in 5% milk in PBS-T (PBS, 0.05% Tween20) for 1 hr, incubated in primary antibody diluted in 5% milk in PBS-T for 2 hr at room temperature or 4°C overnight, and then incubated in secondary antibody conjugated to HRP in 5% milk for 1 hr at room temperature. HRP-conjugated antibodies were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (ECL) (GE Healthcare) and film. The following antibodies were used for Western blot (WB) or immunofluorescence (IF) analysis: Mouse anti-GAPDH (anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; clone 0411; WB analysis 1:10,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-p53 (clone DO1; WB analysis 1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-p21 (WB analysis 1:1000; Millipore), mouse anti-p-p53-ser15 (clone 16G8; WB analysis 1:1000; Cell Signaling), and mouse anti-pUL44 (clone 10D8; WB 1:1000 and IF 1:100; Virusys). Additional CMV antibodies were generously provided by Dr. Tom Shenk (Princeton University): Mouse anti-pUL123 (clone 1B12; WB 1:1000 and IF 1:100) and mouse anti-pp28 (clone 10B4; WB 1:1000). Goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (IgG) conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary antibody was used for Western blot analysis at 1:10,000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody was used for IF analysis at 1:500 (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Nucleic acid levels were determined using quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis. For DNA, cells were collected, resuspended in lysis buffer (400 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K, 0.2% SDS) and incubated at 37°C overnight. DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform and precipitated using ethanol. qPCR was completed using primers to HCMV UL123 or IE1 (5′-GCCTTCCCTAAGACCACCAAT-3′ and 5′-ATTTTCTGGGCATAAGCCATAATC-3′), and cellular GAPDH (5′-ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC-3′ and 5′-CTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCCGT-3′). Quantification was performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master mix (Roche) and the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific). Relative quantities of DNA were determined using an arbitrary standard curve within each experiment for each primer set and normalized to GAPDH levels. For RNA studies, we isolated total RNA from cells using TRIzol Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 2 μg of RNA was treated with DNA-free DNA Removal Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and used to synthesize cDNA with random hexamers and Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific). qPCR was performed as described using primers against CMV UL123, GAPDH and pre-rRNA external transcribed spacer 1 (ETS) (5′-GAACGGTGGTGTGTCGTTC-3′ and 5′-GCGTCTCGTCTCGTCTCACT-3′).

For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were plated in 6-well dishes containing glass coverslips at approximately 60% confluency. After the indicated perturbation, cells were fixed for immunofluorescence analysis using 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min, blocked using 3% BSA in PBS-T for 30 min and then incubated using the indicated primary antibody diluted in 3% BSA in PBS-T for 2 hr at room temperature. Samples were washed three times with PBS-T, incubated using the appropriate Alexa-Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hr at room temperature, and washed. Coverslips were placed on glass slides in Prolong Gold with DAPI antifade reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific). Images were acquired at 60x oil magnification on a Nikon A1 Spectral Confocal Microscope (Nikon) and colocalization coefficients were calculated using NIS-Elements analysis software (Nikon).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Reported values are given as the mean of all replicates ± standard deviation. To calculate statistical significance, the Student t test was used to compare between two samples and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when more than two samples were being analyzed. An asterisk indicates a significant P value of less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 The RNA Polymerase I inhibitor, CX-5461 significantly disrupts HCMV replication

We were interested in determining whether the RNA Polymerase I inhibitor, CX-5461 could inhibit HCMV infection in vitro. Initially, to examine the impact of CX-5461 on cell viability, we treated MRC-5 human fibroblasts with increasing concentrations of CX-5461 or DMSO vehicle control for 48 h (Fig. 1A). We tested CX-5461, ranging from 0.05 μM to 10 μM, for cytotoxic effects by staining for viability using Trypan-Blue and quantifying the percentage of Trypan-Blue-positive cells. At 0.5 μM CX-5461, we observed 7.3% positive cells which is similar to the DMSO vehicle control. At 1, 5 and 10 μM CX-5461, we quantified 23.3%, 64.2% and 98% positive cells, respectively (Fig. 1A). Based on these data, we have used 0.5 μM CX-5461 for the remainder of our studies.

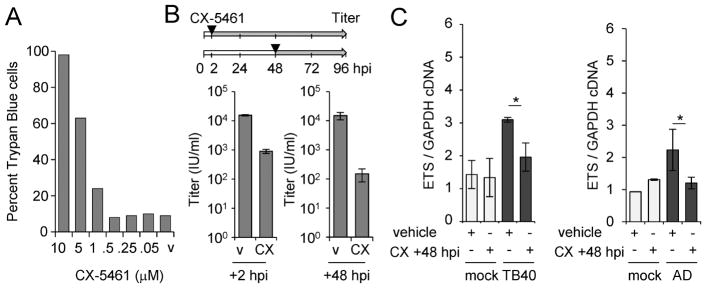

Figure 1. CX-5461 treatment decreases viral titers during HCMV infection.

(A) MRC-5 fibroblasts were treated with 0.05 – 10 μM CX-5461 for 48 hr. Adherent cells were collected and stained with Trypan Blue. Toxicity was determined by counting 100 cells and scoring them as Trypan Blue-positive or -negative. (B) Fibroblasts were infected using the TB40/E virus or mock infected at an MOI of 3 infectious unites per cell. Cells were treated with 0.5 μM CX-5461 or vehicle control at 2 or 48 hpi and changed every 24 h. Viral titers were determined at 96 hpi. (C) Cells were infected with mock, TB40/E (TB40), or AD169 (AD) at an MOI of 3 IU/cell at treated with CX-5461 (CX) starting at 48 hpi. Total RNA was collected at 96 hpi and analyzed using quantitative RT-PCR with primers to the ETS region in pre-rRNA and GAPDH. Data are from three biological replicates and two technical replicates with error bars representing standard deviation from the mean.

To determine the impact of CX-5461 on viral replication, we infected fibroblasts with HCMV TB40/E strain at an MOI of 3 infectious units per cell (IU/cell) and treated with either vehicle or CX-5461 starting at either 2 or 48 hpi (Fig. 1B), replacing the compound every 24 hr. Cell-free virus was collected at 96 hpi and titered. We observed a reduction in viral titers upon CX-5461 treatment starting at either 2 or 48 hpi compared to vehicle (Fig. 1B). The largest change was seen when treatment was started at 48 hpi resulting in a 2.0 log reduction while continuous treatment starting at 2 hpi resulted in a 1.7 log reduction. Next, we quantified pre-ribosomal RNA (pre-rRNA) levels at 96 hpi to determine the impact of CX-5461 on rDNA transcription. Ribosomal DNA is transcribed into a pre-rRNA containing spacer regions including external transcribed spacer (ETS) regions, and we have recently shown that HCMV infection increases pre-rRNA levels (Westdorp et al., 2017). Following CX-5461 or vehicle treatment starting at 48 hpi, we detected decreased pre-rRNA levels in infected but not mock-infected cells (Fig. 1C). These data demonstrate that CX-5461 inhibits HCMV replication and reduce pre-rRNA levels during infection.

3.2 CX-5461 disrupts viral DNA synthesis and late gene expression

To examine the effect of CX-5461 on HCMV, we evaluated viral gene expression and genome replication. We infected fibroblasts at an MOI of 3 IU/cell and treated with CX-5461 or vehicle starting at 2 or 48 hpi. We analyzed IE1 (UL123) RNA levels relative to cellular GAPDH RNA using quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2A). Regardless of the timing of CX-5461 addition, we observed modest decreases in IE1 RNA levels after 48 hpi compared to DMSO control. Next, we quantified the levels of viral DNA following the addition of CX-5461 or vehicle using qPCR and normalized to host cell DNA (Fig. 2B). We observed significant decreases in viral DNA at 72 and 96 hpi when treated with CX-5461 starting at 48 hpi (Fig. 2B). In contrast, addition of CX-5461 starting at 2 hpi resulted in a smaller difference detectable only at 96 hpi.

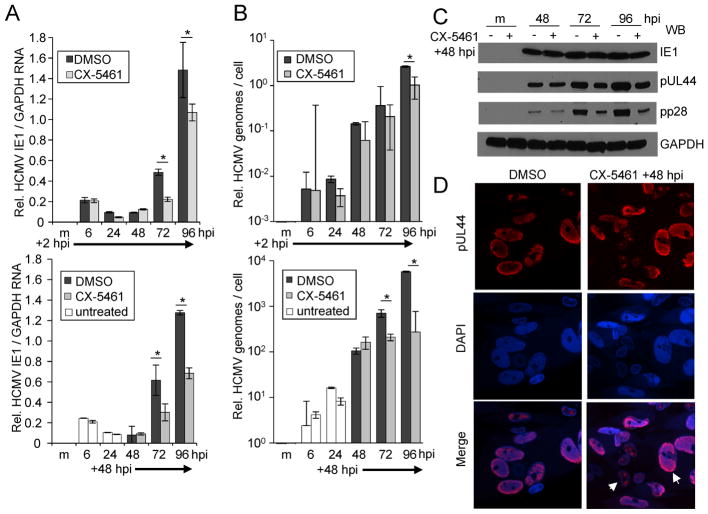

Figure 2. CX-5461 treatment disrupts HCMV replication at the stage of viral DNA synthesis.

(A) MRC-5 fibroblasts were infected with TB40/E virus or mock infected at an MOI of 3 IU/cell. Cells were treated with 0.5 μM CX-5461 or vehicle control at 2 or 48 hpi as indicated. Total RNA was isolated at the indicated times and IE1 and GAPDH levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Under the same conditions, viral DNA levels were determined using quantitative PCR and primers against UL123 and GAPDH. (C) Fibroblasts were infected as above and treated starting at 48 hpi. Whole cell lysates were collected at multiple times post infection and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against the indicated proteins. (D) Samples were fixed 96 hpi and stained using the indicated antibody. Arrows identify two examples of disrupted replication compartments. Quantitative PCR data are from three biological replicates and two technical replicates with error bars representing standard deviation from the mean.

To analyze the impact of CX-5461 on viral protein levels, we infected fibroblasts as above and treated with CX-5461 or vehicle. We have limited these studies to treatment starting at 48 hpi which results in the largest defect in replication. We analyzed protein levels using Western blot analysis and observed similar steady-state levels of IE1 protein out to 96 hpi (Fig. 2C). In contrast, we detected reduced expression for the viral processivity factor, pUL44 and the viral tegument protein, pp28 after 48 hpi (Fig. 2C). We investigated the impact of CX-5461 on the formation of the viral nuclear replication compartment. At 96 hpi, mock and infected cells were fixed and stained with an antibody against HCMV pUL44 (Fig 2D). We observed minor changes in pUL44-positive replication compartments including reduced replication compartment size and organization following CX-5461 addition. HCMV pUL44 contributes to viral DNA synthesis while viral DNA synthesis results in increased pUL44 and pp28 expression. Our data suggest that CX-5461 disrupts infection at the stage of viral DNA synthesis.

3.3 CX-5461 induces a stress response and synergizes with an HCMV kinase inhibitor to disrupt viral replication

The addition of CX-5461 to transformed cells results in increased p53 phosphorylation at serine 15 and increased levels of p21 (Bywater et al., 2012). We were interested in determining whether CX-5461 would alter these proteins in HCMV-infected cells. As described earlier, we infected fibroblasts and added CX-5461 starting at either 2 or 48 hpi. Protein expression levels were evaluated at 96 hpi using Western blot analysis. In mock-infected cells, we observed similar increases in all three species regardless of timing of treatment (Fig. 3A). Following infection, we observed similar levels of p53 and phosphorylated p53 between conditions (Fig. 3A). In contrast, we detected an approximate 12.9-fold increase in p21 levels when CX-5461 was added starting at 48 hpi compared to an approximate 2.9-fold increase when added at 2 hpi (Fig. 3A). We have previously observed that elevated levels of p21 are inhibitory to infection (Bigley et al., 2015) and these data correlate with increased CX-5461 antiviral activity when added at 48 hpi.

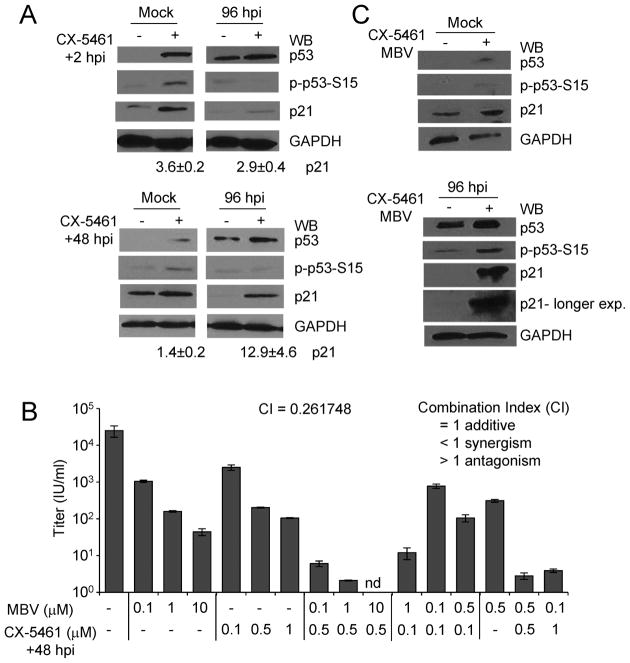

Figure 3. CX-5461 treatment at 48 hpi alters p21 levels and increases the antiviral effects of maribavir.

(A) Fibroblasts were infected with TB40/E virus or mock infected at an MOI of 3. Cells were treated with 0.5 μM CX-5461 or vehicle control at 2 or 48 hpi as indicated. Whole cell lysates were collected at 96 hpi and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against the indicated proteins. The approximate average increase in p21 was determined using densitometry and obtained from two independent experiments. (B) Fibroblasts were infected as above and treated with varying concentrations of maribavir (MBV) at 2 hpi, varying concentrations of CX-5461 at 48 hpi, or cotreated with both compounds. Viral titers were determined at 96 hpi. Data are from two biological replicates and two technical replicates with error bars representing standard deviation from the mean. The average combination index (CI) as determined by CompuSyn software tool is indicated. (C) Fibroblasts were infected with TB40/E virus or mock infected at an MOI of 3 IU/cell. Cells were cotreated with 0.5 μM CX-5461 at 48 hpi and 1 μM MBV or vehicle control as indicated. Whole cell lysates were collected at 96 hpi and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against the indicated proteins.

We have demonstrated that levels of p21 influence the antiviral activity of the HCMV kinase inhibitor, maribavir (Bigley et al., 2015; Reitsma et al., 2011). Next, we wanted to investigate the possible impact of CX-5461 on maribavir activity. Infected fibroblasts were treated with vehicle control or varying concentrations of CX-5461, maribavir, or both compounds (Fig. 3B). We evaluated viral replication by determining titers of cell-free virus at 96 hpi. Titers were reduced upon treatment with either CX-5461 or MBV alone compared to vehicle (Fig. 3B). When 1 μM maribavir and 0.5 μM CX-5461 were used together, we quantified a 4-log reduction in viral titers compared to 2.4-log for 1 μM maribavir only or 2.2-log for 0.5 μM CX-5461 (Fig. 3B). To determine whether the compounds were acting synergistically, we evaluated the resulting titers using the CompuSyn software tool to determine the combination index (CI), where CI<1 indicates synergism, CI=1 indicates an additive effect and CI>1 indicates antagonism between drugs (Chou, 2006). Using non-constant ratio combinations of CX-5461 and maribavir, we calculated an average CI value of 0.26 indicating synergism (Fig. 3B). To test whether p21 levels were further altered upon cotreatment, we evaluated changes using Western blot analysis at 96 hpi (Fig. 3C). We detected a substantial increase in p21 levels occurring when CX-5461 and maribavir were used together compared to vehicle only (Fig. 3C). These data demonstrate that CX-5461 synergizes with maribavir and our finds are consistent with the hypothesis that p21 levels influence HCMV replication and contribute to antiviral activity.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we have demonstrated that CX-5461 inhibits HCMV infection. CX-5461 binds to and stabilizes naturally occurring G-quadruplex DNA structures resulting in inhibition of Pol I-mediated transcription and induction of a DNA damage response (Bywater et al., 2012; Drygin et al., 2011; Quin et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017). Intriguingly, treatment with CX-5461 at 48 hpi leads to a greater reduction in viral titers than treatment at 2 hpi (Fig. 1B) and this is accompanied by elevated levels of p21 (Fig. 3A). Dynamic regulation of p21 occurs during HCMV infection with an immediate early induction followed by subsequent loss at later times involving changes in both gene expression and protein stability (Chen et al., 2001). In addition, early during infection, HCMV expresses multiple proteins to circumvent the inhibitory effects of cellular stress signaling on viral replication (Alwine, 2008). It is conceivable that inhibiting Pol I late during infection renders the virus more susceptible to replication defects due to the lack of protective viral stress regulators expressed at later stages. Sustained levels of p21 disrupt both viral DNA synthesis and, following inhibition of the viral kinase, virion egress (Bigley et al., 2015). Alternatively, it is possible that the HCMV genomes contain G-quadruplex structures which are targeted by CX-5461. Sequence analysis of HCMV TB40/E identified 1381 putative quadruplex forming G-rich sequences (Kikin et al., 2006). We report here that treating HCMV infected cells with CX-5461 in combination with the viral kinase inhibitor, maribavir synergizes to disrupt infection. Recent studies have indicated that the drug emetine, another example of a pharmaceutical that induces a nucleolar stress response, exhibits antiviral effects against HCMV and synergizes with the anti-HCMV drug ganciclovir (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2016). The identification of pharmaceuticals that synergize with one another has the potential to significantly improve outcomes in patients with bacterial and viral infections, including those infected with HCMV.

Highlights.

The Pol I inhibitor, CX-5461 significantly disrupts HCMV replication.

Increased CX-5461 antiviral activity correlates with elevated p21 levels.

CX-5461 synergizes with the HCMV kinase inhibitor, maribavir.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the NIAID of the NIH R01 AI083281 to S. Terhune. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. We thank Tom Shenk for the HCMV antibodies, Carol Williams and Patrick Gonyo for reagents and advice on nucleolar biology, and members of the Terhune lab.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alwine JC. Modulation of host cell stress responses by human cytomegalovirus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:263–279. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderholm KM, Bierle CJ, Schleiss MR. Cytomegalovirus Vaccines: Current Status and Future Prospects. Drugs. 2016;76:1625–1645. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0653-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek MC, Krosky PM, He Z, Coen DM. Specific phosphorylation of exogenous protein and peptide substrates by the human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein kinase. Importance of the P+5 position. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29593–29599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigley TM, Reitsma JM, Terhune SS. Antagonistic Relationship between Human Cytomegalovirus pUL27 and pUL97 Activities during Infection. J Virol. 2015;89:10230–10246. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00986-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron KK, Harvey RJ, Chamberlain SC, Good SS, Smith AA, 3rd, Davis MG, Talarico CL, Miller WH, Ferris R, Dornsife RE, Stanat SC, Drach JC, Townsend LB, Koszalka GW. Potent and selective inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by 1263W94, a benzimidazole L-riboside with a unique mode of action. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2002;46:2365–2372. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.8.2365-2372.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt WJ. Congenital Human Cytomegalovirus Infection and the Enigma of Maternal Immunity. J Virol. 2017:91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02392-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bywater MJ, Poortinga G, Sanij E, Hein N, Peck A, Cullinane C, Wall M, Cluse L, Drygin D, Anderes K, Huser N, Proffitt C, Bliesath J, Haddach M, Schwaebe MK, Ryckman DM, Rice WG, Schmitt C, Lowe SW, Johnstone RW, Pearson RB, McArthur GA, Hannan RD. Inhibition of RNA polymerase I as a therapeutic strategy to promote cancer-specific activation of p53. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Knutson E, Kurosky A, Albrecht T. Degradation of p21cip1 in cells productively infected with human cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2001;75:3613–3625. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3613-3625.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacological reviews. 2006;58:621– 681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drygin D, Lin A, Bliesath J, Ho CB, O’Brien SE, Proffitt C, Omori M, Haddach M, Schwaebe MK, Siddiqui-Jain A, Streiner N, Quin JE, Sanij E, Bywater MJ, Hannan RD, Ryckman D, Anderes K, Rice WG. Targeting RNA polymerase I with an oral small molecule CX-5461 inhibits ribosomal RNA synthesis and solid tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1418–1430. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner T, Hewlett G, Ettischer N, Ruebsamen-Schaeff H, Zimmermann H, Lischka P. The novel anticytomegalovirus compound AIC246 (Letermovir) inhibits human cytomegalovirus replication through a specific antiviral mechanism that involves the viral terminase. J Virol. 2011;85:10884–10893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05265-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakki M, Chou S. The biology of cytomegalovirus drug resistance. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2011;24:605–611. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834cfb58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A, Wang Y, Raje H, Rosby R, DiMario P. Nucleolar stress with and without p53. Nucleus (Austin, Tex) 2014;5:402–426. doi: 10.4161/nucl.32235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikin O, D’Antonio L, Bagga PS. QGRS Mapper: a web-based server for predicting G-quadruplexes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W676–682. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischka P, Hewlett G, Wunberg T, Baumeister J, Paulsen D, Goldner T, Ruebsamen-Schaeff H, Zimmermann H. In vitro and in vivo activities of the novel anticytomegalovirus compound AIC246. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2010;54:1290– 1297. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01596-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Griffiths PD, Pass RF. Cytomegaloviruses. In: PM, KDMH, editors. Fields Virology. 6. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2013. pp. 1960–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R, Roy S, Venkatadri R, Su YP, Ye W, Barnaeva E, Mathews Griner L, Southall N, Hu X, Wang AQ, Xu X, Dulcey AE, Marugan JJ, Ferrer M, Arav-Boger R. Efficacy and Mechanism of Action of Low Dose Emetine against Human Cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005717. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Yu D, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Jarvis MA, Hahn G, Nelson JA, Myers RM, Shenk TE. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14976–14981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136652100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quin J, Chan KT, Devlin JR, Cameron DP, Diesch J, Cullinane C, Ahern J, Khot A, Hein N, George AJ, Hannan KM, Poortinga G, Sheppard KE, Khanna KK, Johnstone RW, Drygin D, McArthur GA, Pearson RB, Sanij E, Hannan RD. Inhibition of RNA polymerase I transcription initiation by CX-5461 activates non-canonical ATM/ATR signaling. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49800–49818. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsma JM, Savaryn JP, Faust K, Sato H, Halligan BD, Terhune SS. Antiviral inhibition targeting the HCMV kinase pUL97 requires pUL27-dependent degradation of Tip60 acetyltransferase and cell-cycle arrest. Cell host & microbe. 2011;9:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinzger C, Hahn G, Digel M, Katona R, Sampaio KL, Messerle M, Hengel H, Koszinowski U, Brune W, Adler B. Cloning and sequencing of a highly productive, endotheliotropic virus strain derived from human cytomegalovirus TB40/E. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:359–368. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westdorp KN, Sand A, Moorman NJ, Terhune SS. Cytomegalovirus Late Protein pUL31 Alters Pre-rRNA Expression and Nuclear Organization during Infection. J Virol. 2017:91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00593-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Di Antonio M, McKinney S, Mathew V, Ho B, O’Neil NJ, Santos ND, Silvester J, Wei V, Garcia J, Kabeer F, Lai D, Soriano P, Banath J, Chiu DS, Yap D, Le DD, Ye FB, Zhang A, Thu K, Soong J, Lin SC, Tsai AH, Osako T, Algara T, Saunders DN, Wong J, Xian J, Bally MB, Brenton JD, Brown GW, Shah SP, Cescon D, Mak TW, Caldas C, Stirling PC, Hieter P, Balasubramanian S, Aparicio S. CX-5461 is a DNA G-quadruplex stabilizer with selective lethality in BRCA1/2 deficient tumours. Nature communications. 2017;8:14432. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]