Abstract

Background

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an esophageal inflammatory disease associated with atopic diseases. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and calpain 14 (CAPN14) genetic variations contribute to EoE, but how this relates to atopy is unclear.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between EoE, atopy, and genetic risk.

Methods

EoE-atopy enrichment was tested by using 700 patients with EoE and 801 community control subjects. Probing 372 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 63 atopy genes, we evaluated EoE associations using 412 nonatopic and 868 atopic disease control subjects. Interaction and stratified analyses of EoE-specific and atopy-related SNPs were performed.

Results

Atopic disease was enriched in patients with EoE (P < .0001). Comparing patients with EoE and nonatopic control subjects, EoE associated strongly with IL-4/kinesin family member 3A (IL4/KIF3A) (P = 2.8 × 10−6; odds ratio [OR], 1.87), moderately with TSLP (P = 1.5 × 10−4; OR, 1.43), and nominally with CAPN14 (P = .029; OR, 1.35). Comparing patients with EoE with atopic disease control subjects, EoE associated strongly with ST2 (P = 3.5 × 10−6; OR, 1.77) and nominally with IL4/KIF3A (P = .019; OR, 1.25); TSLP’s association persisted (P = 4.7 × 10−5; OR, 1.37), and CAPN14’s association strengthened (P = .0001; OR, 1.71). Notably, there was gene-gene interaction between TSLP and IL4 SNPs (P = .0074). Children with risk alleles for both genes were at higher risk for EoE (P = 2.0 × 10−10; OR, 3.67).

Conclusions

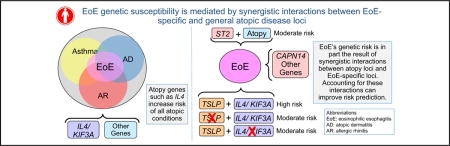

EoE genetic susceptibility is mediated by EoE-specific and general atopic disease loci, which can have synergistic effects. These results might aid in identifying potential therapeutics and predicting EoE susceptibility.

Keywords: Genetic association, atopy, eosinophilic esophagitis

Graphical abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a food antigen–driven, esophagus-specific inflammatory disease associated with allergic inflammation and occurring in 1 in 2000 subjects.1 EoE is typified by eosinophil-predominant infiltration of the esophagus that is often associated with difficulty swallowing and abdominal pain.2 Successful treatments include food elimination and swallowed glucocorticoids, which is consistent with an atopic inflammatory process. Indeed, patients with EoE report high atopic disease rates.1,3–9

Strong familial clustering implicates a genetic basis for EoE.10–12 Notably, multiple genome-wide association studies have identified disease susceptibility loci encoding thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and calpain 14 (CAPN14).13–15 TSLP is a key epithelial cell–derived immune cytokine that regulates TH2 responses, especially those involving IL-4 and IL-13 production. TSLP has been implicated in the atopic march and EoE.16–22 CAPN14 is expressed in the esophagus and stimulated by IL-13,15 and CAPN14 dysregulation is associated with impaired epithelial barrier function.23,24 Importantly, TH2 responses are characteristic of atopy. However, it is unclear whether EoE risk variants interact with those contributing to atopy.

Thus the purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between EoE, atopy, and genetic risk. Here we evaluated the effect of nonatopic and atopic disease control subjects on EoE genetic associations and evaluated gene-gene interaction. We found a striking association of the IL4/KIF3A locus with EoE compared with nonatopic control subjects. When using atopic disease control subjects, we found an association with ST2. TSLP and CAPN14 were associated regardless of the control set. Importantly, we found evidence of interaction between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at IL4 and TSLP, such that TSLP risk variants most strongly associate with EoE when the IL4 risk variant is present.

METHODS

Study design

To explore the relationship between EoE, atopy, and genetic risk, we used a multistep process. First, we sought to verify that atopic disease (asthma, atopic dermatitis [AD], allergic rhinitis [AR], and/or food allergy) was enriched in patients with EoE. To accomplish this, we compared rates of self-reported asthma, eczema, AR, and food allergy, as well as rates of at least 1 atopic disease, between patients with EoE and a set of community-based participants without EoE. We then sought to determine whether EoE genetic associations differed when using nonatopic versus atopic disease control subjects. Atopic disease control subjects were drawn from a hospital-based cohort that included participants with a physician’s diagnosis of atopic disease. Nonatopic control subjects were drawn from the community-based control subjects. All cohorts were recruited in a similar time frame. To further evaluate EoE by using atopic disease, we then performed gene-gene interaction analyses between EoE-associated SNPs and an IL4 SNP that has been consistently associated with atopic disease.25–30 Analyses were restricted to subjects who self-identified as white. Participants were enrolled in institutional review board–approved protocols.

Study populations

Patients with EoE

Patients from the Cincinnati Center for Eosinophilic Disorders were offered enrollment into a repository that allows collection of information and samples from patients. For this study, the inclusion criterion was a confirmed diagnosis of EoE (the presence of upper gastrointestinal tract symptoms and an endoscopy with ≥15 eosinophils/high-power field in proximal or distal esophageal tissue biopsy specimens per consensus recommendations31) in childhood. Of note, approximately 15% of the EoE cohort overlaps with the prior study by Sherrill et al.32 In this follow-up study genotyping was performed on a different platform, and we evaluated a different set of atopic disease control subjects.

Atopic disease control subjects

The Greater Cincinnati Pediatric Clinic Repository is a cohort of children with and without allergic disease.33 Pediatric patients visiting the Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonary Clinics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center provided saliva DNA samples, approved use of their clinical data, and answered questionnaires.33

Community control subjects

The Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort is an institutional review board–approved cohort of children from the greater Cincinnati metropolitan area.15,34 Data were collected by using questionnaires; blood samples were collected for serum and DNA. Children with self-reported gastrointestinal disease were excluded.

Atopic phenotypes

For the atopic disease control subject, atopic disease phenotypes came from a specialty physician’s diagnosis (AD from a dermatology or allergy clinic, asthma from a pulmonary or allergy clinic, and AR from an allergy clinic). For the EoE cohort and community control subjects, atopic disease phenotypes were based on parental report. To clarify food allergy further, we evaluated the proportion of children with EoE who were documented as being prescribed epinephrine (EoE cohort) or reported anaphylaxis (community cohort). Children from the community cohort with no reported asthma, AD (or eczema), AR, hay fever, or food allergy were used as nonatopic control subjects. Children from the community cohort with self-reported atopic disease were not included with atopic disease control subjects.

Genotyping

To overcome multiple testing concerns and maximally use prior knowledge about atopic disease risk, we developed a custom Illumina SNP chip entitled Epithelial Gene Array for Allergic Disorders (Illumina, San Diego, Calif; the full list of genes and SNPs is shown in Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Genes were selected for inclusion on a custom Illumina GoldenGate Assay (http://www.illumina.com) based on function and relevance to the epithelium, asthma, AD, immunity, and EoE. Gene-specific tagging SNPs were selected by using HapMap Genome Browser release no. 24 in the CEU and YRI populations and had an r2 value of 0.8 or less and a minor allele frequency of 10% or more in either population. This chip contains 668 SNPs in 80 genes related to the epithelium and atopy plus 100 ancestry-informative markers (AIMs). The EoE and atopic disease cohorts were genotyped with this custom chip. Thirty-one SNPs failed genotyping, 134 were excluded for low minor allele frequency (<0.1), and 29 were excluded because of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium deviations (P <.00001). In addition, rs10192210 in CAPN14 was genotyped in all cohorts by using TaqMan assays.

The community and EoE cohorts were also genotyped on the Illumina OMNI5 platform for the purpose of a genome-wide association study. A total of 371 SNPs overlapped between OMNI5 and the Epithelial Gene Array for Allergic Disorders plus the CAPN14 SNP from TaqMan, resulting in 372 SNPs. To account for genetic ancestry, principal component (PC) analyses were performed on AIMs by using EIGENSTRAT.35

Statistical analysis

Analyses were restricted to those whose genetic ancestry supported European descent (99.8%). Primary association screens compared patients with EoE with atopic disease control subjects and nonatopic control subjects (from the Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort, excluding patients with asthma, AD, AR, or food allergy). Logistic regression was used to test for associations with EoE, with variants coded additively and sex and age included as covariates. The genomic inflation factor was estimated by using AIMs. Both the patients with EoE versus atopic disease control subjects and patients with EoE versus nonatopic control subjects exhibited evidence of population stratification (genomic inflation factor = 1.49 and 1.36, respectively). PCs were included as covariates to control for population stratification (patients with EoE vs atopic disease control subjects, 4 PCs; patients with EoE vs nonatopic control subjects, 3 PCs; PC-adjusted genomic inflation factor = 1 for both). In the screen the threshold for significance was an α value of 0.00036 after linkage disequilibrium (LD)–adjusted Bonferroni correction.

Given EoE’s association with SNPs of IL4, CAPN14, and TSLP, we performed gene-gene interaction analyses between the IL4 variant (rs2243250, previously reported to be functional36) and TSLP and CAPN14 variants by using logistic regression and incorporating IL4 SNPs by using the TSLP and CAPN14 SNP interaction term. For interaction analyses, the LD-adjusted Bonferroni correction was an α value of .0125. To explore these relationships further, we performed analyses stratified by the presence and absence of rs2243250, examining both P values and odds ratios (ORs). To evaluate synergistic effects between TSLP (rs3806933) and IL4 (rs2243250), we categorized subjects into 4 levels: those with (1) no risk alleles at either locus, (2) at least 1 risk allele at IL4 but not TSLP, (3) at least 1 risk allele at TSLP but not IL4, and (4) at least 1 risk allele at both loci. We performed logistic regression to determine how the combination of these 2 loci was associated with EoE compared with community control subjects. All analyses were performed by using R software.

RESULTS

Description of study cohort

We included 700 children with EoE, 868 children with atopic disease (asthma, AD, and/or AR but not EoE), and 801 community control subjects, 412 of whom were nonatopic (Table I).33 The EoE cohort was more male and slightly younger than the community cohort and slightly older than the atopic disease cohort.

TABLE I.

Cohort characteristics and enrichment of atopic disease in patients with EoE

| Patients with EoE | Community control subjects* | Nonatopic control subjects† | Atopic disease control subjects‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 700 | 801 | 412 | 868 |

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 9.63 ± 9.37 | 11.03 ± 4.21¶ | 10.86 ± 4.29║ | 7.92 ± 4.89# |

| Male sex (%) | 75.7 | 49.4# | 47.6# | 56.7# |

| Atopic disease (%) | 94.2 | 48.7# | 0 | 100 |

| Asthma (%) | 49.0 | 12.3# | — | 62.4 |

| AD (%) | 51.5 | 17.4# | — | 41.7 |

| AR (%) | 73.0 | 34.5# | — | 66.5 |

| Food allergy (%) | 80.4 | 6.9# | — | NA |

| Two or more atopic diseases (%) | 75.1 | 14.3# | — | 55.5# |

No comparisons were made for rates of atopic disease between patients with EoE and atopic and nonatopic disease cohorts. NA, Not assessed.

P < .01,

P < .001, and

P < .0001 compared with patients with EoE.

Community control subjects were derived from the Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort.

Nonatopic control subjects are a subset of community control subjects.

Atopic disease control subjects were from the Greater Cincinnati Pediatric Clinical Repository, as previously reported.33

Atopic disease is enriched in patients with EoE

To determine the degree of atopic disease enrichment in patients with EoE, we compared patients with EoE with community control subjects (Table I). Atopic disease prevalence was markedly higher in children with EoE than in community control subjects (P < .0001). There was also marked enrichment for each atopic disease in patients with EoE (P < .0001). The prevalence of self-reported food allergy was high in patients with EoE and low in the community control subjects. Nearly half of the children with EoE were prescribed epinephrine (47.8%). In control subjects only 0.46% of the children reported food-induced anaphylaxis, which can be a proxy for clinically diagnosed food allergy. These data support an enrichment of atopic diseases in children with EoE.

Genetic associations with EoE differ when using nonatopic and atopic disease control subjects

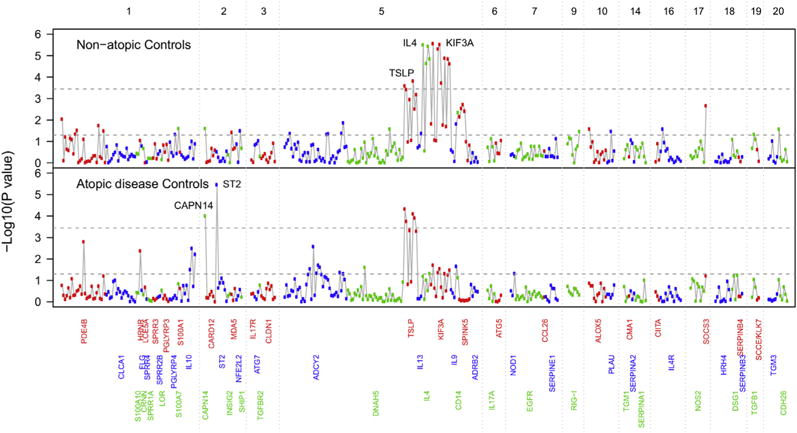

When we compared patients with EoE with nonatopic control subjects (Fig 1 and see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org) across 372 SNPs in 63 genes, the strongest genetic associations with EoE were detected at the IL4/KIF3A locus: 10 SNPs were associated at a P value of less than 10−4, 5 of which were associated at a P value of less than 10−5 (OR range, 1.85-1.89). Although there are many associated variants in this locus, there is strong LD in this region, and thus these signals are not independent (see Fig E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The TSLP locus exhibited association (best P = 1.5 × 10−4; OR, 1.43 for risk allele). Likewise, strong LD in this locus means these signals are not independent (see Fig E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). SNPs at CAPN14 exhibited nominal association (P = .029; OR, 1.35). In addition, SNPs in several other genes (SPINK5, SOCS3, CD14, and PDE4B) showed association (P < .01) with EoE. In contrast, when we compared patients with EoE with atopic disease control subjects (Fig 1 and Fig 2 and see Table II), the association between EoE and the IL4/KIF3A locus was nominally significant (best P = .019; OR range, 1.11-1.25). However, the association between TSLP SNPs and EoE persisted (best P = 4.7 × 10−5; OR, 1.37 for risk allele). Furthermore, association between EoE and the CAPN14 SNP strengthened (P = .0001; OR, 1.71).

FIG 1.

Genetic associations with EoE differ by control group. IL4 is a predominant association when using nonatopic control subjects. TSLP is a predominant association when using atopic disease control subjects. The y-axis is the −log10 P value. Numbers on the top x-axis denote chromosomes. Within a chromosome, variants are ordered by genomic position.

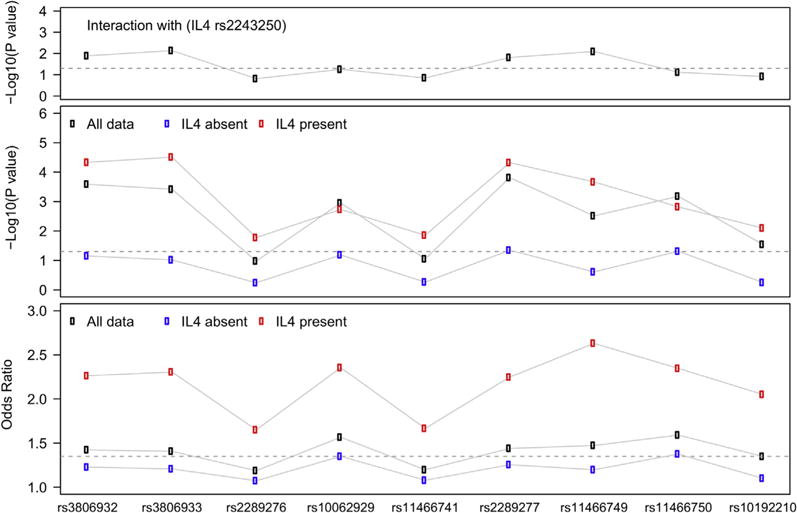

FIG 2.

Interaction between IL4 and TSLP. IL4 and TSLP variants exhibit significant interaction (top panel). In subjects with at least 1 copy of the IL4 risk variant (rs2243250), TSLP is strongly associated with EoE; however, in subjects lacking this variant, the association is only nominal (middle panel). Subjects with IL4 risk variants have substantially larger effect sizes (OR) than subjects lacking the IL4 risk variant (bottom panel).

TABLE II.

Associations (P ≤ .01) with EoE using nonatopic and atopic disease control subjects

| Chromosome | BP | SNP | Gene | Alleles (minor/major) | MAF† | MAF | Patients with EoE vs nonatopic control subjects | Patients with EoE vs atopic disease control subjects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | P value | OR | P value | |||||||

| 1 | 66,276,985 | rs4288570 | PDE4B | G/A | 0.27 | 0.28 | 1.31 (1.07-1.60)* | .0091 | 1.12 (0.95-1.32)* | .17 |

| 1 | 66,683,452 | rs544361 | PDE4B | A/G | 0.27 | 0.24 | 1.22 (0.98-1.52)* | .08 | 1.34 (1.12-1.61)* | .002 |

| 1 | 152,185,184 | rs4845745 | HRNR | G/A | 0.16 | 0.21 | 1.24 (0.97-1.60) | .09 | 1.32 (1.09-1.6)* | .004 |

| 1 | 206,944,645 | rs1518111 | IL10 | A/G | 0.21 | 0.24 | 1.21 (0.97-1.51)* | .10 | 1.32 (1.10-1.58)* | .003 |

| 1 | 206,946,407 | rs1800872 | IL10 | A/C | 0.21 | 0.25 | 1.18 (0.95-1.46)* | .13 | 1.28 (1.07-1.53)* | .006 |

| 2 | 31,415,077 | rs10192210 | CAPN14 | A/G | 0.17 | 0.16 | 1.35 (1.04-1.83) | .029 | 1.71 (1.31-2.25) | .0001 |

| 2 | 102,938,389 | rs1420089 | ST2 | G/A | 0.12 | 0.15 | 1.17 (0.87-1.57)* | .30 | 1.77 (1.39-2.25)* | 3.5E-06 |

| 5 | 7,537,575 | rs9313195 | ADCY2 | A/G | 0.33 | 0.36 | 1.16 (0.95-1.40)* | .14 | 1.27 (1.09-1.49)* | .0026 |

| 5 | 7,801,371 | rs16879141 | ADCY2 | G/A | 0.09 | 0.14 | 1.39 (1.07-1.81)* | .01 | 1.25 (1.01-1.57)* | .049 |

| 5 | 110,405,675 | rs3806932 | TSLP | G/A | 0.46 | 0.43 | 1.42 (1.18-1.72)* | .00026 | 1.37 (1.18-1.61) | 4.7E-05 |

| 5 | 110,406,742 | rs3806933 | TSLP | A/G | 0.44 | 0.41 | 1.41 (1.17-1.70)* | .00038 | 1.34 (1.15-1.57)* | .00018 |

| 5 | 110,408,179 | rs10062929 | TSLP | A/C | 0.14 | 0.14 | 1.57 (1.20-2.05)* | .0011 | 1.50 (1.20-1.89)* | .00047 |

| 5 | 110,409,067 | rs2289277 | TSLP | C/G | 0.45 | 0.42 | 1.43 (1.19-1.74)* | .00015 | 1.37 (1.17-1.60)* | 8.0E-05 |

| 5 | 110,412,585 | rs11466749 | TSLP | G/A | 0.17 | 0.17 | 1.47 (1.14-1.90)* | .0031 | 1.52 (1.23-1.87)* | .00012 |

| 5 | 110,412,894 | rs11466750 | TSLP | A/G | 0.14 | 0.14 | 1.59 (1.22-2.08)* | .00066 | 1.49 (1.19-1.87)* | .00051 |

| 5 | 132,009,154 | rs2243250 | IL4 | A/G | 0.13 | 0.17 | 1.89 (1.45-2.47) | 3.2E-06 | 1.20 (0.99-1.45) | .06 |

| 5 | 132,013,963 | rs2243268 | IL4 | C/A | 0.13 | 0.17 | 1.78 (1.36-2.32) | 2.3E-05 | 1.18 (0.97-1.43) | .10 |

| 5 | 132,014,832 | rs2243274 | IL4 | A/G | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1.85 (1.43-2.41) | 3.7E-06 | 1.11 (0.92-1.33) | .29 |

| 5 | 132,016,554 | rs2243282 | IL4 | A/C | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.80 (1.38-2.34) | 1.4E-05 | 1.21 (1.01-1.47) | .048 |

| 5 | 132,033,612 | rs2237059 | KIF3A | A/G | 0.14 | 0.17 | 1.87 (1.44-2.43) | 2.8E-06 | 1.25 (1.04-1.51) | .019 |

| 5 | 132,040,069 | rs12186803 | KIF3A | A/G | 0.13 | 0.17 | 1.85 (1.42-2.42) | 4.9E-06 | 1.22 (1.01-1.48) | .043 |

| 5 | 132,042,146 | rs3798130 | KIF3A | A/G | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.89 (1.44-2.46) | 3.0E-06 | 1.24 (1.02-1.5) | .029 |

| 5 | 132,043,032 | rs2299007 | KIF3A | G/A | 0.13 | 0.16 | 1.68 (1.28-2.20) | .00019 | 1.14 (0.93-1.39) | .21 |

| 5 | 132,046,590 | rs7737031 | KIF3A | A/G | 0.13 | 0.17 | 1.80 (1.38-2.35) | 1.3E-05 | 1.21 (1.01-1.47) | .048 |

| 5 | 132,069,739 | rs9784675 | KIF3A | G/A | 0.14 | 0.17 | 1.78 (1.37-2.31) | 1.4E-05 | 1.20 (1.00-1.45) | .06 |

| 5 | 132,069,847 | rs9784600 | KIF3A | A/C | 0.20 | 0.17 | 1.75 (1.35-2.26) | 2.4E-05 | 1.23 (1.02-1.49) | .033 |

| 5 | 140,011,468 | rs4914 | CD14 | C/G | 0.09 | 0.12 | 1.50 (1.13-1.98) | .005 | 1.24 (0.98-1.58) | .07 |

| 5 | 147,442,868 | rs1423007 | SPINK5 | G/A | 0.44 | 0.38 | 1.29 (1.07-1.56) | .0072 | 1.02 (0.88-1.18) | .27 |

| 5 | 147,451,451 | rs7445392 | SPINK5 | G/A | 0.49 | 0.50 | 1.31 (1.10-1.57) | .0029 | 1.01 (0.88-1.17) | .22 |

| 5 | 147,475,386 | rs6892205 | SPINK5 | A/G | 0.49 | 0.49 | 1.32 (1.11-1.58) | .0019 | 1.01 (0.88-1.17) | .13 |

| 5 | 147,480,027 | rs2303063 | SPINK5 | G/A | 0.49 | 0.49 | 1.30 (1.09-1.55) | .0039 | 1.01 (0.87-1.17) | .17 |

| 17 | 76,353,793 | rs4969168 | SOCS3 | A/G | 0.14 | 0.12 | 1.56 (1.17-2.07) | .0022 | 1.23 (0.99-1.53) | .06 |

Boldface P values reach multiple testing adjustment (P ≤ .00036). ORs are in reference to the risk allele. BP, Base pairs; MAF, minor allele frequency.

The major allele is the risk allele, and the minor allele is protective.

MAFs was obtained from HapMap CEU.

SNPs in several other genes (ST2, PDE4B, ADCY2, IL10, and HRNR) also exhibited association (P <.01) with EoE when using atopic disease control subjects (Table II). Notably, the strongest association with EoE when using atopic disease control subjects, the ST2 (IL1RL1) gene (P = 3.5 × 10−6; OR, 1.77), was not significant when using nonatopic control subjects (P = .30; OR, 1.17).

Collectively, these results suggest that TSLP and CAPN14 genetic variation associate specifically with EoE, IL4/KIF3A is an atopic disease locus, and ST2 might require underlying atopic disease to associate with EoE. Importantly, IL4 and KIF3A are in strong LD (see Fig E1). Thus determining which of the 2 genes is responsible for the association cannot be achieved statistically. However, previous work has implicated IL4 in atopic responses including those in EoE,37–39 thereby justifying our focus on IL4.

Gene-gene interaction between IL4 and TSLP

We then tested whether the most strongly associated IL4 variant (rs2243250) interacted with TSLP and CAPN14 SNPs. In interaction analyses multiple TSLP SNPs exhibited significant interaction (best P = .0074, Fig 3). However, the interaction between IL4 and CAPN14 was not significant (P = .12). Given that the allele frequency is greater for TSLP SNPs than for CAPN14 SNP, it is possible that we were underpowered to detect an interaction between IL4 and CAPN14 SNPs. Several genes associated with EoE when using atopic disease control subjects (ST2, ADCY2, and IL10) also exhibited nominal evidence (P <.05) of interaction with IL4. Given the strength of interaction between IL4 and TSLP, we stratified by the presence or absence of the IL4 risk variant and showed that associations (both P values and ORs) of the TSLP SNPs with EoE were stronger when the IL4 risk variant was present (Fig 2). Similar effects were seen when evaluating KIF3A variants (data not shown).

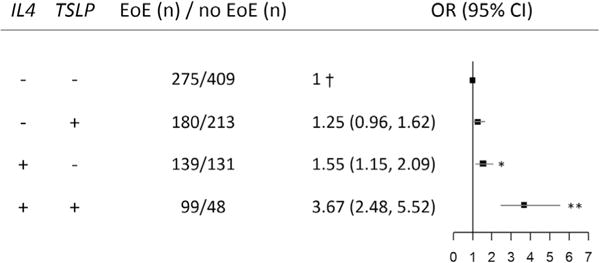

FIG 3.

Synergistic effect of IL4 and TSLP risk alleles for patients with EoE versus population-representative control subjects (Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort). †Reference category, subjects with neither risk allele. IL4 risk allele, rs2243250; TSLP risk allele, rs3806933. *P < .05 and **P < .001. ORs were adjusted for sex, age, and PCs.

When evaluating the effect of inheriting no risk alleles from IL4 and TSLP compared with only one or both, we found that inheriting a risk allele from one of these 2 genes was associated with modest risk increases (IL4: P = .004, OR of 1.55; TSLP: P = .10, OR of 1.25). However, children with risk alleles from both genes had a synergistic increased risk for EoE (P = 2.0 × 10−10; OR, 3.67). Of note, having risk alleles from both IL4 and TSLP compared with having neither risk allele is highly specific (90% adjusting for no covariates), supporting the fact that having both risk alleles is highly predictive of EoE. Notably, the sensitivity is low (26%, adjusting for no covariates), suggesting that not having both risk alleles does not rule out EoE. Taken together, these data suggest that the IL4 locus interacts with the TSLP locus to influence EoE risk.

DISCUSSION

Here we investigated the relationship between EoE, atopy, and genetic risk. Prior work identified TSLP and CAPN14 genetic variation associated with EoE. Both genes have been implicated in TH2 responses, a critical atopy component. Thus understanding the relationship between EoE susceptibility and atopic disease is germane to elucidating shared disease mechanisms. Our study demonstrated that EoE susceptibility is mediated by EoE-specific and general atopic disease loci, which can have synergistic effects. First, we demonstrate that children with EoE are markedly enriched for other atopic diseases (food allergy, asthma, AD, and AR). Second, we demonstrate that IL4/KIF3A strongly associates with EoE by using nonatopic control subjects, suggesting that the atopic disease component of EoE is underpinned by a factor or factors encoded by the IL4/KIF3A locus. Third, we demonstrate the persistence of TSLP and CAPN14 associations and an association with ST2 using atopic disease control subjects, supporting their specific role in EoE. Lastly, we identify an interaction between IL4 and TSLP SNPs, demonstrating a synergistic effect.

Taken together, these results provide novel evidence that EoE genetic associations might be conditional on atopy, which helps explain, at least in part, the high degree of comorbidity of atopic disease in patients with EoE. These results demonstrate the interplay of multiple genetic susceptibility loci for EoE and might help explain in part the high degree of comorbidity of atopic disease in patients with EoE.

Our study is the first to report a gene-gene interaction in patients with EoE, in particular between IL4 and TSLP, such that subjects carrying risk variants in both genes compared with those carrying none have a synergistic increased EoE risk (OR, 3.67). Previous reports have demonstrated that IL4 interacts with IL4R, FCER1B, and ADRB2 for high serum IgE levels40 and ADRB2 for asthma.25 Other studies have implicated TSLP genetic variation in patients with EoE13–15,32,41,42 and reported TSLP interacting with SPINK5 for asthma.43 In addition, IL4 and TSLP are upregulated in esophageal tissue from patients with EoE.13,17,44 There are multiple TSLP SNPs exhibiting this interaction, but the strong LD in this gene suggests these are not independent effects. HaploReg identifies multiple TSLP variants (including rs3806933, which exhibited the strongest evidence of interaction) that are expression quantitative trait loci, histone marks for promoters, enhancers, DNAs, and altered motifs.45 Biologically, this interaction is plausible because TSLP is involved directly with TH2-mediated responses through IL4 in-duction.46,47 Increased IL4 expression is sufficient to promote allergic responses.48,49 Importantly, TSLP can drive this allergic inflammatory response16,39,50–53 but might be most critical early in TH2 immune responses.54 There is also evidence that TSLP can be induced by activated TH2 cells and thus might participate with IL4 in a positive feedback loop to enhance allergic inflammation.55 Taken together, these studies support our novel finding of a genetic interaction between TSLP and IL4/KIF3A loci.

Our study also found that the genetic association of CAPN14 with EoE is present when using nonatopic and atopic disease control subjects. Previous work has implicated CAPN14 in patients with EoE.14,15,41,42 However, our study found that the OR was markedly greater when using atopic disease control subjects. It is important to note that although there was not statistical evidence of interaction between IL4 and CAPN14 (P = .12), this might be ascribed to the low allele frequency of the CAPN14 variant because we were underpowered to detect such an effect; thus future studies are warranted. There is substantial evidence that CAPN14 is involved in TH2 signaling. Specifically, CAPN14 is upregulated in epithelial cells in response to IL456 and IL13.15,23 Interestingly, nickel exposure, which can cause contact dermatitis, is associated with increased CAPN14 expression.57,58 Furthermore, there are documented cases of dietary nickel allergy with gastrointestinal symptoms.59–61 These studies offer potential mechanisms through which CAPN14 can act in concert with atopy.

Using nonatopic control subjects, we observed that the strongest association of EoE was with the IL4/KIF3A locus. These results replicated the findings of a previous phenotype-driven analysis.62 However, the strength of this association became markedly attenuated when using atopic disease control subjects. Previous studies have reported associations between IL4 (specifically rs2243250) and asthma,25,29,30,63–65 AD,27,28,66,67 and AR,26,68,69 as well as functional evidence.36 Furthermore, GTEx analysis demonstrates that rs2243250 is associated with altered IL4 expression,70 and HaploReg analysis predicts that this SNP is associated with enhancer histone marks and an altered Sox motif.45 The strong associations between IL4 and atopic disease (EoE, asthma, AD, and AR) suggest that the IL4/KIF3A locus is a general atopy locus. These 2 genes are part of the TH2 cytokine locus, which includes RAD50, IL5, and IL13. IL4 and KIF3A are in strong LD,71 making it difficult to discern which gene or SNP is driving the association with EoE.63 However, KIF3A is expressed constitutively, whereas IL4 is expressed in response to T-cell differentiation, suggesting a critical role for IL4 in atopic response.72 Furthermore, in our previous analyses of gene expression in the esophagi of patients with EoE, we have shown that IL4 expression is associated with dysphagia, supporting its role in EoE.73 Thus genetic variation at the IL4 locus likely contributes to overall atopic disease risk.

Using atopic disease control subjects, we identified an ST2 (IL1RL1) SNP that strongly associated with EoE (P = 3.5 × 10−6; OR, 1.77). Although not previously associated with EoE, ST2 genetic variants (including rs1420089) have been associated with increased eosinophil counts and serum IgE levels and atopic disease.74–77 ST2 is a member of the IL-1 superfamily and binds to IL-33 to drive TH2 cytokine production.78 ST2 is expressed by eosinophils and basophils, and its binding with IL-33 induces potent cellular activation.79–81 ST2 is also expressed in group 2 innate lymphoid cells,82 which have been implicated in food allergy.83 Furthermore, group 2 innate lymphoid cell levels are greater in patients with active EoE than in patients with nonactive EoE or nondiseased control subjects.84 These data support a potential role of ST2 in patients with EoE in the context of atopy.

Our observation that IL4 and TSLP interact has several clinical implications. First, by accounting for the risk of IL4 and TSLP in combination, we found a highly specific effect (OR, 3.67; specificity, 0.90 compared with those with neither risk allele). This high degree of risk might allow for identifying a subgroup of EoE. However, studies to identify other risk factors are warranted because the failure to carry both alleles does not rule out EoE.

Second, the existence of this interaction might help explain the high rate of atopy in patients with EoE. Indeed, 80% or more of patients with EoE report asthma, AD, and/or AR.5

Third, this IL4-TSLP interaction might also help explain how treatments can be broadly effective against a variety of atopic diseases. For example, the topical corticosteroid fluticasone is used in patients with asthma, AD,85–87 and AR88 and is also effective for EoE.89–94 However, this lack of specificity might also help explain why there is substantial steroid resistance at the tissue and clinical level in patients with EoE.73 Thus drugs, such as humanized anti-TSLP antibody, anti–IL-13, and/or anti–IL-4 receptor α therapies, which show promise for the treatment of asthma,95,96 may also work alone or in combination for EoE.

In conclusion, these results are the first to report that EoE susceptibility is mediated by EoE-specific and general atopic disease loci, which can have synergistic effects, suggesting that EoE genetic associations are likely conditional on atopic disease. The demonstrated novel genetic interaction between IL4 and TSLP might help explain in part the high degree of atopic disease comorbidity present in children with EoE. These results suggest that the discovery of risk genes and variants for EoE will be highly dependent on the control cohort. Stratifying by known atopic disease genes (eg, IL4/KIF3A) can also be used to strengthen variants that can act in the context of underlying atopy. Because of the possibility of gene-gene interaction, it is critical to phenotype both cases and control subjects or to perform stratified analyses to minimize underlying heterogeneity. The identified shared genetic effects might help in identifying drugs to treat the underlying allergic inflammation across tissues and provide opportunities to better predict disease susceptibility and brings EoE one step closer to benefiting from precision medicine based on analysis of the interaction of multiple genotypes.

Supplementary Material

Clinical implications.

EoE susceptibility is mediated by multiple genes that have synergistic effects. These genes include both EoE-specific and general atopic disease loci. Identifying these effects might help customize treatment.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants U19 AI70235, R01 AI124355, R01 DK107502, and P30 AR070549; the Sunshine Charitable Foundation and its supporters, Denise A. Bunning and David G. Bunning; the American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED); the Buckeye Foundation; the Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Diseases (CURED) Foundation; and the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation and its Cincinnati Genomic Control Cohort.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: L. J. Martin’s, H. He’s, and M. Eby’s institutions received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for this work. M. H. Collins’s institution received a grant from the NIH for this work, she personally received consultancy fees from Regeneron and Banner Life Sciences, and her institution received support from Shire contract for pathology central review and Regeneron contract for pathology central review. J. P. Abonia’s institution received grants from the NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; CEGIR) U54AI117804, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) SC14-1403-11593, and NIH/NIAID (CoFAR) 2U19 AI066738-06 for this work. J. M. Biagini Myers’ institute received a grant and support for travel from the NIH for this study and grants from the NIH for other works. H. Johansson’s institute received a grant from the NIH for this work. L. C. Kottyan’s institute received grant R01 DK107502, P30 AR070549 for this work. G. Khurana Hershey’s institution received a grant from the NIH for this and other works. M. E. Rothenberg’s institution received a grant from the NIH for this work and grants from US-Israel Binational Grant and PCORI for other works; his institution owns patents inventorship, ownership by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and he personally received consultancy fees from Celgene, Genentech, Immune Pharmaceuticals, NKT Therapeutics, Spoon Guru, and PulmOneTherapeutics; payment for lectures from Merck; and stock options from PulmOne, NKT Therapeutics, and Spoon Guru, Immune Pharmaceuticals.

Abbreviations

- AD

Atopic dermatitis

- AIM

Ancestry-informative marker

- AR

Allergic rhinitis

- CAPN14

Calpain 14

- EoE

Eosinophilic esophagitis

- IL4/KIF3A

IL-4/kinesin family member 3A

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- OR

Odds ratio

- PC

Principal component

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TSLP

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin

Footnotes

The CrossMark symbol notifies online readers when updates have been made to the article such as errata or minor corrections

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:589–96.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins MH. Histopathology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis. 2014;32:68–73. doi: 10.1159/000357012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBrosse CW, Franciosi JP, King EC, Butz BK, Greenberg AB, Collins MH, et al. Long-term outcomes in pediatric-onset esophageal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernon N, Shah S, Lehman E, Ghaffari G. Comparison of atopic features between children and adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:409–14. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spergel JM, Andrews T, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Liacouras CA. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with specific food elimination diet directed by a combination of skin prick and patch tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95:336–43. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assa’ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Akers RM, Jameson SC, Kirby CL, et al. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:731–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro Jimenez A, Gomez Torrijos E, Garcia Rodriguez R, Feo Brito F, Borja Segade J, Galindo Bonilla PA, et al. Demographic, clinical and allergological characteristics of eosinophilic esophagitis in a Spanish central region. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2014;42:407–14. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa DF, Katzka DA. Atopic characteristics of adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:531–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chadha SN, Wang L, Correa H, Moulton D, Hummell DS. Pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: the Vanderbilt experience. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander ES, Martin LJ, Collins MH, Kottyan LC, Sucharew H, He H, et al. Twin and family studies reveal strong environmental and weaker genetic cues explaining heritability of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1084–92.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins MH, Blanchard C, Abonia JP, Kirby C, Akers R, Wang N, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and molecular characterization of familial eosinophilic esophagitis compared with sporadic cases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:621–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:289–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sleiman PM, Wang ML, Cianferoni A, Aceves S, Gonsalves N, Nadeau K, et al. GWAS identifies four novel eosinophilic esophagitis loci. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5593. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kottyan LC, Davis BP, Sherrill JD, Liu K, Rochman M, Kaufman K, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis provides insight into the tissue specificity of this allergic disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:895–900. doi: 10.1038/ng.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demehri S, Morimoto M, Holtzman MJ, Kopan R. Skin-derived TSLP triggers progression from epidermal-barrier defects to asthma. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noti M, Wojno ED, Kim BS, Siracusa MC, Giacomin PR, Nair MG, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1005–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harada M, Hirota T, Jodo AI, Hitomi Y, Sakashita M, Tsunoda T, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin gene promoter polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:787–93. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0418OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunninghake GM, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Kim HP, Lasky-Su J, Rafaels N, et al. TSLP polymorphisms are associated with asthma in a sex-specific fashion. Allergy. 2010;65:1566–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu M, Rogers L, Cheng Q, Shao Y, Fernandez-Beros ME, Hirschhorn JN, et al. Genetic variants of TSLP and asthma in an admixed urban population. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torgerson DG, Ampleford EJ, Chiu GY, Gauderman WJ, Gignoux CR, Graves PE, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:887–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allakhverdi Z, Comeau MR, Jessup HK, Yoon BR, Brewer A, Chartier S, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is released by human epithelial cells in response to microbes, trauma, or inflammation and potently activates mast cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:253–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis BP, Stucke EM, Khorki ME, Litosh VA, Rymer JK, Rochman M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis-linked calpain 14 is an IL-13-induced protease that mediates esophageal epithelial barrier impairment. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e86355. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Litosh VA, Rochman M, Rymer JK, Porollo A, Kottyan LC, Rothenberg ME. Calpain-14 and its association 1 with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1762–71.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baye TM, Butsch Kovacic M, Biagini Myers JM, Martin LJ, Lindsey M, Patterson TL, et al. Differences in candidate gene association between European ancestry and African American asthmatic children. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu MP, Chen RX, Wang ML, Zhu XJ, Zhu LP, Yin M, et al. Association study on IL4, IL13 and IL4RA polymorphisms in mite-sensitized persistent allergic rhinitis in a Chinese population. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussein YM, Shalaby SM, Nassar A, Alzahrani SS, Alharbi AS, Nouh M. Association between genes encoding components of the IL-4/IL-4 receptor pathway and dermatitis in children. Gene. 2014;545:276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Guia RM, Ramos JD. The -590C/TIL4 single-nucleotide polymorphism as a genetic factor of atopic allergy. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2010;1:67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Arakawa M. Relationship between polymorphisms in IL4 and asthma in Japanese women: the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto LA, Stein RT, Kabesch M. Impact of genetics in childhood asthma. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2008;84:S68–75. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–22.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherrill JD, Gao PS, Stucke EM, Blanchard C, Collins MH, Putnam PE, et al. Variants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:160–5.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butsch Kovacic M, Biagini Myers JM, Lindsey M, Patterson T, Sauter S, Ericksen MB, et al. The Greater Cincinnati Pediatric Clinic Repository: a novel framework for childhood asthma and allergy research. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2012;25:104–13. doi: 10.1089/ped.2011.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovacic MB, Myers JM, Wang N, Martin LJ, Lindsey M, Ericksen MB, et al. Identification of KIF3A as a novel candidate gene for childhood asthma using RNA expression and population allelic frequencies differences. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenwasser LJ, Klemm DJ, Dresback JK, Inamura H, Mascali JJ, Klinnert M, et al. Promoter polymorphisms in the chromosome 5 gene cluster in asthma and atopy. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25(suppl 2):74–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1995.tb00428.x. discussion 95-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Burwinkel K, Caldwell JM, Collins MH, Ahrens A, et al. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4033–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt-Weber CB. Anti-IL-4 as a new strategy in allergy. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2012;96:120–5. doi: 10.1159/000332235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tatsuno K, Fujiyama T, Yamaguchi H, Waki M, Tokura Y. TSLP directly interacts with skin-homing Th2 cells highly expressing its receptor to enhance IL-4 production in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:3017–24. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Guia RM, Echavez MD, Gaw EL, Gomez MR, Lopez KA, Mendoza RC, et al. Multifactor-dimensionality reduction reveals interaction of important gene variants involved in allergy. Int J Immunogenet. 2015;42:182–9. doi: 10.1111/iji.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothenberg ME. Molecular, genetic, and cellular bases for treating eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1143–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sleiman PM, March M, Hakonarson H. The genetic basis of eosinophilic esophagitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29:701–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biagini Myers JM, Martin LJ, Kovacic MB, Mersha TB, He H, Pilipenko V, et al. Epistasis between serine protease inhibitor Kazal-type 5 (SPINK5) and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) genes contributes to childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:891–9.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vicario M, Blanchard C, Stringer KF, Collins MH, Mingler MK, Ahrens A, et al. Local B cells and IgE production in the oesophageal mucosa in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2010;59:12–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.178020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D930–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Omori M, Ziegler S. Induction of IL-4 expression in CD4(1) T cells by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J Immunol. 2007;178:1396–404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rochman I, Watanabe N, Arima K, Liu YJ, Leonard WJ. Cutting edge: direct action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin on activated human CD41 T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:6720–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perkins C, Wills-Karp M, Finkelman FD. IL-4 induces IL-13-independent allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:410–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tepper RI, Levinson DA, Stanger BZ, Campos-Torres J, Abbas AK, Leder P. IL-4 induces allergic-like inflammatory disease and alters T cell development in transgenic mice. Cell. 1990;62:457–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He R, Oyoshi MK, Garibyan L, Kumar L, Ziegler SF, Geha RS. TSLP acts on infiltrating effector T cells to drive allergic skin inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11875–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801532105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leyva-Castillo JM, Hener P, Jiang H, Li M. TSLP produced by keratinocytes promotes allergen sensitization through skin and thereby triggers atopic march in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:154–63. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang H, Hener P, Li J, Li M. Skin thymic stromal lymphopoietin promotes airway sensitization to inhalant house dust mites leading to allergic asthma in mice. Allergy. 2012;67:1078–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Z, Hener P, Frossard N, Kato S, Metzger D, Li M, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin overproduced by keratinocytes in mouse skin aggravates experimental asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1536–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812668106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jang S, Morris S, Lukacs NW. TSLP promotes induction of Th2 differentiation but is not necessary during established allergen-induced pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dewas C, Chen X, Honda T, Junttila I, Linton J, Udey MC, et al. TSLP expression: analysis with a ZsGreen TSLP reporter mouse. J Immunol. 2015;194:1372–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ueta M, Mizushima K, Yokoi N, Naito Y, Kinoshita S. Expression of the interleukin-4 receptor alpha in human conjunctival epithelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1239–43. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.173419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Correa da Rosa J, Malajian D, Shemer A, Rozenblit M, Dhingra N, Czarnowicki T, et al. Patients with atopic dermatitis have attenuated and distinct contact hypersensitivity responses to common allergens in skin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:712–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhingra N, Shemer A, Correa da Rosa J, Rozenblit M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gittler JK, et al. Molecular profiling of contact dermatitis skin identifies allergen-dependent differences in immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:362–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ricciardi L, Arena A, Arena E, Zambito M, Ingrassia A, Valenti G, et al. Systemic nickel allergy syndrome: epidemiological data from four Italian allergy units. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27:131–6. doi: 10.1177/039463201402700118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Antico A, Soana R. Nickel sensitization and dietary nickel are a substantial cause of symptoms provocation in patients with chronic allergic-like dermatitis syndromes. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 2015;6:56–63. doi: 10.2500/ar.2015.6.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Gioacchino M, Ricciardi L, De Pita O, Minelli M, Patella V, Voltolini S, et al. Nickel oral hyposensitization in patients with systemic nickel allergy syndrome. Ann Med. 2014;46:31–7. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2013.861158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Namjou B, Marsolo K, Caroll RJ, Denny JC, Ritchie MD, Verma SS, et al. Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) in EMR-linked pediatric cohorts, genetically links PLCL1 to speech language development and IL5-IL13 to Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Front Genet. 2014;5:401. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marenholz I, Esparza-Gordillo J, Ruschendorf F, Bauerfeind A, Strachan DP, Spycher BD, et al. Meta-analysis identifies seven susceptibility loci involved in the atopic march. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8804. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dmitrieva-Zdorova EV, Voronko OE, Latysheva EA, Storozhakov GI, Archakov AI. Analysis of polymorphisms in T(H)2-associated genes in Russian patients with atopic bronchial asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22:126–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu N, Gong Y, Chen XD, Zhang J, Long F, He J, et al. Association between the polymorphisms of interleukin-4, the interleukin-4 receptor gene and asthma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:2943–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.He JQ, Chan-Yeung M, Becker AB, Dimich-Ward H, Ferguson AC, Manfreda J, et al. Genetic variants of the IL13 and IL4 genes and atopic diseases in at-risk children. Genes Immun. 2003;4:385–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawashima T, Noguchi E, Arinami T, Yamakawa-Kobayashi K, Nakagawa H, Otsuka F, et al. Linkage and association of an interleukin 4 gene polymorphism with atopic dermatitis in Japanese families. J Med Genet. 1998;35:502–4. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.6.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Black S, Teixeira AS, Loh AX, Vinall L, Holloway JW, Hardy R, et al. Contribution of functional variation in the IL13 gene to allergy, hay fever and asthma in the NSHD longitudinal 1946 birth cohort. Allergy. 2009;64:1172–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu S, Chan-Yeung M, Becker AB, Dimich-Ward H, Ferguson AC, Manfreda J, et al. Polymorphisms of the IL-4, TNF-alpha, and Fcepsilon RIbeta genes and the risk of allergic disorders in at-risk infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1655–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9906086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.GTEx Consortium. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee DU, Rao A. Molecular analysis of a locus control region in the T helper 2 cytokine gene cluster: a target for STAT6 but not GATA3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16010–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407031101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santangelo S, Cousins DJ, Winkelmann NE, Staynov DZ. DNA methylation changes at human Th2 cytokine genes coincide with DNase I hypersensitive site formation during CD4(1) T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2002;169:1893–903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martin LJ, Franciosi JP, Collins MH, Abonia JP, Lee JJ, Hommel KA, et al. Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis Symptom Scores (PEESS v2.0) identify histologic and molecular correlates of the key clinical features of disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1519–28.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gudbjartsson DF, Bjornsdottir US, Halapi E, Helgadottir A, Sulem P, Jonsdottir GM, et al. Sequence variants affecting eosinophil numbers associate with asthma and myocardial infarction. Nat Genet. 2009;41:342–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shimizu M, Matsuda A, Yanagisawa K, Hirota T, Akahoshi M, Inomata N, et al. Functional SNPs in the distal promoter of the ST2 gene are associated with atopic dermatitis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2919–27. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reijmerink NE, Postma DS, Bruinenberg M, Nolte IM, Meyers DA, Bleecker ER, et al. Association of IL1RL1, IL18R1, and IL18RAP gene cluster polymorphisms with asthma and atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:651–4.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu H, Romieu I, Shi M, Hancock DB, Li H, Sienra-Monge JJ, et al. Evaluation of candidate genes in a genome-wide association study of childhood asthma in Mexicans. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:321–7.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Venturelli N, Lexmond WS, Ohsaki A, Nurko S, Karasuyama H, Fiebiger E, et al. Allergic skin sensitization promotes eosinophilic esophagitis through the IL-33-basophil axis in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1367–80.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bouffi C, Rochman M, Zust CB, Stucke EM, Kartashov A, Fulkerson PC, et al. IL-33 markedly activates murine eosinophils by an NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism differentially dependent upon an IL-4-driven autoinflammatory loop. J Immunol. 2013;191:4317–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Travers J, Rochman M, Miracle CE, Cohen JP, Rothenberg ME. Linking impaired skin barrier function to esophageal allergic inflammation via IL-33. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1381–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walker JA, Barlow JL, McKenzie AN. Innate lymphoid cells—how did we miss them? Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:75–87. doi: 10.1038/nri3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Noval Rivas M, Burton OT, Oettgen HC, Chatila T. IL-4 production by group 2 innate lymphoid cells promotes food allergy by blocking regulatory T-cell function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:801–11.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Doherty TA, Baum R, Newbury RO, Yang T, Dohil R, Aquino M, et al. Group 2 innate lymphocytes (ILC2) are enriched in active eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:792–4.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Korting HC, Schollmann C. Topical fluticasone propionate: intervention and maintenance treatment options of atopic dermatitis based on a high therapeutic index. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:133–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Peden DB, Berger WE, Noonan MJ, Thomas MR, Hendricks VL, Hamedani AG, et al. Inhaled fluticasone propionate delivered by means of two different multidose powder inhalers is effective and safe in a large pediatric population with persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:32–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adams NP, Bestall JC, Lasserson TJ, Jones P, Cates CJ. Fluticasone versus placebo for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD003135. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003135.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meltzer EO, Bensch GW, Storms WW. New intranasal formulations for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35(suppl 1):S11–9. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Assa’ad AH, Guajardo JR, Jameson SC, et al. Clinical and immunopathologic effects of swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:568–75. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Butz BK, Wen T, Gleich GJ, Furuta GT, Spergel J, King E, et al. Efficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:324–33.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Corkins MR, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, Enders F, Katzka DA, Kephardt GM, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:742–9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Boldorini R, Mercalli F, Oderda G. Eosinophilic oesophagitis in children: responders and non-responders to swallowed fluticasone. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66:399–402. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Dias JA, Baker TP, Maydonovitch CL, Wong RK. Randomized controlled trial comparing aerosolized swallowed fluticasone to esomeprazole for esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:366–72. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gauvreau GM, O’Byrne PM, Boulet LP, Wang Y, Cockcroft D, Bigler J, et al. Effects of an anti-TSLP antibody on allergen-induced asthmatic responses. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2102–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Beck LA, Thaci D, Hamilton JD, Graham NM, Bieber T, Rocklin R, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.