Abstract

The study describes the development of a vaccine using microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel PH-101) as a delivery carrier of recombinant protein-based antigen against erysipelas. Recombinant SpaA, surface protective protein, from a gram-positive pathogen Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae was fused to a cellulose-binding domain (CBD) from Trichoderma harzianum endoglucanase II through a S3N10 peptide. The fusion protein (CBD-SpaA) was expressed in Escherichia coli and was subsequently bound to Avicel PH-101. The antigenicity of CBD-SpaA bound to the Avicel was evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) and confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) assays. For the examination of its immunogenicity, groups of mice were immunized with different constructs (soluble CBD-SpaA, Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA, whole bacterin of E. rhusiopathiae (positive control), and PBS (negative control)). In two weeks after immunization, mice were challenged with 1x107 CFU of E. rhusiopathiae and Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA induced protective immunity in mice. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the feasibility of microcrystalline cellulose as the delivery system of recombinant protein subunit vaccine against E. rhusiopathiae infection in mice.

1. Introduction

Vaccines are the therapeutic formulations given to patients to elicit immune responses entailing antibody production (humoral) or cell-mediated responses that will eventually fight variety of malignancies [1]. There have been many approaches for vaccine delivery via vaccinations, which are considered the most efficient prophylactic method against various infectious diseases. Vaccine delivery systems (i.e., micro- or nanoparticles, liposomes, and virosomes) have been investigated for improving vaccine efficacy [2–5]. In addition, various vaccine types have been developed to overcome the disadvantages of conventional vaccines. Among vaccines, recombinant protein antigens, or their fragments, have been used and considered as novel vaccine candidates. Development of such kinds of vaccines avoids the safety issues with attenuating virus or cell cultures when making conventional viral vaccines [6, 7]. However, some recombinant protein antigens have fatal handicaps (low stability and immunogenicity) caused by lack of key elements that can stimulate immune response [8]. Use of adjuvants, along with recombinant protein vaccines, has been suggested for improved immunogenicity [9]. Different strategies have been extensively explored in order to improve the immunogenicity by protecting antigens through immobilization on inorganic or organic matrices [10].

Cellulose is a primary component of plant cell walls and a linear polymer of glucose residues. It is naturally resistant to biological degradation owing to its insolubility, rigidity, and tendency to pack together to form long crystals. It is chemically inert, pharmaceutically safe, and inexpensive, making it an effective immunosorbent, or carrier material, for protein purification and immobilization [11]. Cellulose-binding domain (CBD) refers to protein modules that bind firmly to various types of cellulose. The strong attraction between cellulose and CBD has applications in many areas, especially for immunology [12]. In previous studies, cellulose beads (Sigmacell 20® or Orbicell™ cellulose particles) attached to CBD-fused recombinant protein were used for parenteral vaccination for goldfish [13], and the immunogenic properties of CBD in its free form were compared with the CBD-cellulose complex, using cytokine production as an immunological indicator. Small Orbicell beads (1–10 μM) induced antibody levels that were equal to the titers produced by the adjuvanted protein and bacterin formulae compared to the larger Sigmacell particles (10–20 μM). Similarly, Lunin et al. (2009) studied the immobilization of CBD on the cellulose sorbent which enhances the synthesis of specific antibodies and found that cellulose immunosorbent is not immunotolerant and could induce cytokine production involved in the regulation of humoral immune response [8].

Erysipelas is a very serious swine disease causing tremendous economic loss. E. rhusiopathiae, causative agent of erysipelas, is a gram-positive, rod shaped, non-spore-forming, non-motile, and bacterial pathogen [14]. Although live-attenuated or recombinant vaccines are currently administered to control this disease, their effectiveness is not consistent. Even the mechanisms of pathogenicity have not yet been elucidated [15–18]. Therefore, it is necessary to have a more advanced and effective system of vaccination against erysipelas.

In this study, we developed Avicel (cellulose microcrystalline) correlated with antigen and investigated its characteristics. In addition, antigen-immobilized Avicel vaccine was subcutaneously injected into mice to analyze the actual immunogenicity of our newly developed antigen-immobilized Avicel recombinant protein vaccine. Overall, the study highlights the development of an efficient recombinant protein vaccine-immunosorbent system to protect swine against E. rhusiopathiae infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

The E. rhusiopathiae serotype 15 strain was isolated from a diseased piglet in Korea. For it, E. coli DH5α [F−, ϕ80dlacZΔM15, endA1 hsdR17 (rK−, mK+), supE44, thi-1, λ−, recA1, gyrA96] was used as a host strain for cloning and plasmid maintenance. The E. coli BL21 host strain [F−, hsdS, gal, ompT, rB−, mB−] (Novagen, USA), harboring a lambda derivative, DE3, was used for gene expression.

2.2. Cloning and Recombinant Plasmid Construction

The gene coding CBD of Trichoderma harzianum endoglucanase II, with artificial S3N10 linker, was amplified from pEKPM-EcGAD-Lk-H6 (Ahn, 2004; Hyemin Park, 2012) using specific primers (Forward: 5′-GAAGGAGATATACATATGCAGCAAACTGTTTGGGGG-3′, Reverse: 5′-CTTCTTATCGGATCCGTTGTTGTTGTTGTTGTTGTTGTTGTTGTTGCTGCTGCTAATGCATTGAGCGTAGTA-3′), in which the underlined characters were introduced for the In-fusion™ Advantage PCR cloning kit (Clontech, USA). The italic letters indicate the site of the restriction enzymes. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product containing CBD with S3N10 linker was introduced into the pET-28b(+) plasmid (Novagen, USA), previously digested with NdeI and BamHI. For the isolation of genomic DNA of E. rhusiopathiae, a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used according to manufacturer's instructions. The surface protective antigen A (SpaA) gene was amplified from E. rhusiopathiae genomic DNA, by PCR using the primers (Forward: 5′-ACTCCGCCAACTAGCTCTGGATCCGATTCGACAGATATTTCTG-3′, Reverse: 5′-GTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTCGAGTTTTAAACTTCCATCGTTC), in which underlined base pairs were introduced for In-fusion ligation. The italic letters indicate the sites of BamHI and XhoI.

2.3. Expression and Purification of CBD-SpaA Protein

The plasmid harboring pKPM-CBD-Lk-SpaA-H6 was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). The transformants were grown in 2YT medium containing 50 μg/ml of kanamycin at 37°C. When an A600 of 0.5 was reached, 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-thio-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) was added and cultures were grown for an additional 3h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and pellets were disrupted by sonication for further analysis. Recombinant fusion protein was purified from the supernatant by Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Germany), using an Econo-Pac Chromatography Column (Bio-Rad, USA) according to the manufacturer instructions. The protein concentration was estimated using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, USA).

2.4. Binding of CBD-SpaA onto Avicel

Binding assays were carried out according to methods previously described, with slight modification [19]. Briefly, Avicel (PH-101, Sigma, < 50 μm) (0.1 mg) was mixed with 500 μg of the CBD-SpaA proteins at 4°C for 2 h. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation and used to determine uncombined protein using a BCA protein assay kit. The amount of protein bound to Avicel was determined from the difference between final and starting values in the supernatant. Nonspecific proteins bound to Avicel were removed by washing with 0.5 M NaCl.

2.5. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot Analysis

SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) was performed according to the method of Laemmle [20]. For the Western blot analyses, proteins separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gel were transferred to nitrocellulose (NC) membranes. The NC membranes were blocked by phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% skimmed milk and washed three times with PBST (0.1% Tween 20 in PBS). The membranes were incubated with His-probe monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) or mouse-derived antiserum prepared with whole bacteria of E. rhusiopathiae, for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The specific antigen reacted with IgG alkaline phosphatase (AP) antibody (Sigma, USA) was visualized using an AP conjugated substrate kit (Bio-Rad, USA).

2.6. Preparation of Polyclonal Mouse Antiserum

To prepare mouse polyclonal antiserum against E. rhusiopathiae, a five-week-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mouse was injected subcutaneously with formalinized whole cell vaccine of E. rhusiopathiae twice within a 2-week interval. Then, a blood sample was collected two weeks later and sera antibody titer was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

2.7. Antigenicity Evaluation

Microtiter assembly strips (Thermo Scientific, Finland) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl per well of immobilized CBD-SpaA on Avicel. Several dilutions (1×104, 5×104, 1×105, and 5×105 Avicel particles) of Avicel coated CBD-SpaA were tested in triplet. The plates were washed three times with PBST and blocked with 5% skimmed milk in PBST for 1h at RT. Antiserum derived from mouse against E. rhusiopathiae (1:500) was added to the plates and then placed on a rocker platform for 2h at RT. For the detection of immunogenic characteristics, the plates were incubated with a 1:2000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) anti-mouse IgG whole antibody (GE Healthcare, UK) for 1 h at RT. Optical density was read at 450 nm using a TECAN Infinity 2000 PRO plate reader (TECAN, Austria).

2.8. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM)

Avicel particles (1×105) coated with CBD-SpaA were incubated with antiserum against E. rhusiopathiae (1:500) for 2h at RT. After washing three times with PBST, the immobilized CBD-SpaA was incubated with Fluorescein- (FITC-) AffiniPure F(ab')2 Fragment Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab, USA) for 30 min at 4°C. The plate was washed again, and Avicel particles coated with CBD-SpaA were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at RT, followed by mounting with VECTASHIELD mount medium (Vector Lab., USA). Immunofluorescence was evaluated using an LSM 510 META Laser Scanning Microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

2.9. Mouse Immunization and Challenge

Forty SPF mice (5 weeks old) were randomly assigned to 4 groups of eight each and injected subcutaneously with 4 μg of soluble CBD-SpaA, Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA, ERT2T-A containing whole bacterin of E. rhusiopathiae serovar 15 (positive control), and PBS (negative control) emulsified with an oil-based adjuvant, respectively. Two weeks after injection, all groups were challenged subcutaneously with 1×107 CFU of E. rhusiopathiae (serovar 15). Mouse mortality was monitored daily for the following ten days.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of the CBD-SpaA Fusion Protein in E. coli

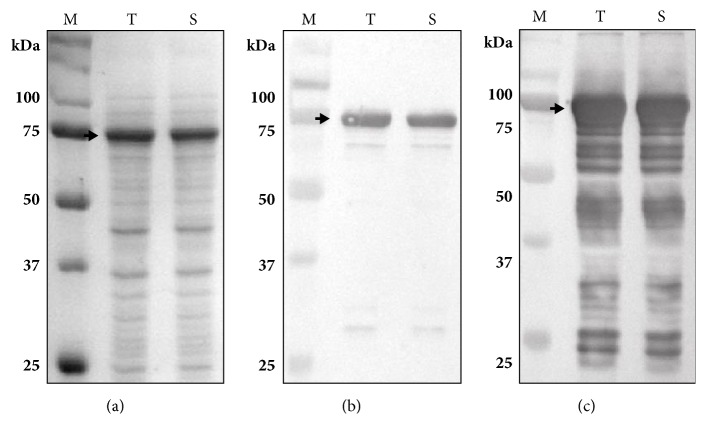

As illustrated in Figure 1, pKPM-CBD-Lk-SpaA-H6 was constructed for the expression of SpaA fused to CBD. In the construct, SpaA was fused to CBD from T. harzianum endoglucanase II via an artificial S3N10 peptide known to completely resist E. coli endopeptidase at its N-terminus and six histidines at its C-terminus. The fusion protein (CBD-SpaA) was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pKPM-CBD-Lk-SpaA-H6. The results of the SDS-PAGE and Western blot (Figure 2) indicated that the CBD-SpaA was successfully expressed at the expected molecular weight (77.6 kDa) without being degraded by proteolysis and that the CBD-SpaA was overexpressed at a high level (35%) with respect to the percentage of total cell protein. Moreover, most of the expressed CBD-SpaA were in soluble form, compared to our previous work in which extreme reduction of the solubility of E. coli-derived glutamate decarboxylase occurred after fusion with CBD [21].

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the expression vector for CBD-SpaA-H6 fusion protein. SpaA, surface protective antigen A (SpaA) from E. rhusiopathiae; CBD, the cellulose-binding domain of T. harzianum endoglucanase II; Linker, S3N10 peptide; (His)6, 6x histidine tag sequence; T7lac, T7 promoter sequence; T7t, T7 terminator sequence.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses of the CBD-SpaA-H6 expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pKPM-CBD-SpaA-H6: (a) SDS-PAGE; (b) Western blot with anti-histidine antibody; (c) anti-serum derived from mouse inoculated with whole E. rhusiopathiae. Lane M: standard molecular weight marker, T: total cell lysates, and S: soluble fraction proteins. The arrows indicate the expressed CBD-SpaA.

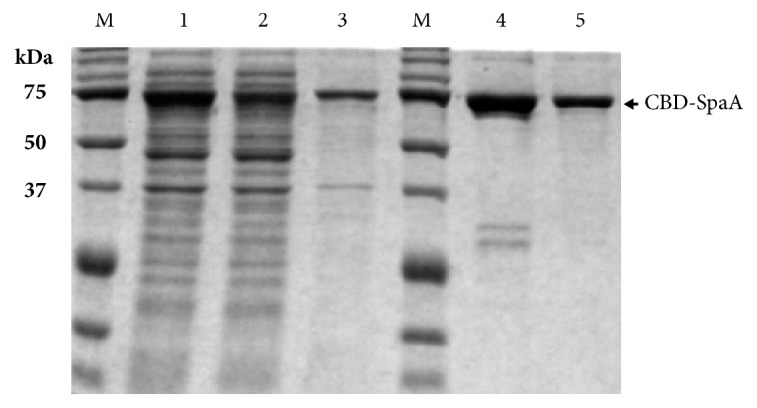

3.2. Coating of Avicel with CBD-SpaA Protein

The CBD-SpaA proteins from crude cell lysates were purified through a Ni-NTA column with the elution of an imidazole (250 mM). The elution fraction contained CBD-SpaA with a purity of 85.1%. Both the purified CBD-SpaA and crude cell lysates were bound to microcrystalline cellulose Avicel PH-101 and the concentration of CBD-SpaA bound to Avicel was determined by stripping the protein from the beads by boiling. Avicel displayed a binding capacity of 3.11±0.015 mgCBD-SpaA/gAvicel (purity: 94%) for the purified CBD-SpaA and 1.92±0.001 mgCBD-SpaA/gAvicel (purity: 81%) for crude cell lysates (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Coating of Avicel with CBD-SpaA protein. Lanes 1-3: crude CBD-SpaA and Lanes 4 and 5: purified CBD-SpaA. Lane M: stand molecular weight marker, Lanes 1 and 4: proteins before binding to Avicel, Lane 2: proteins not bound to Avicel, and Lanes 3 and 5: proteins bound on Avicel.

3.3. Antigenicity of CBD-SpaA Bound to Avicel

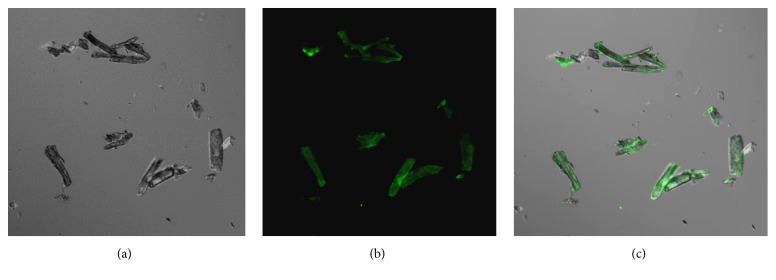

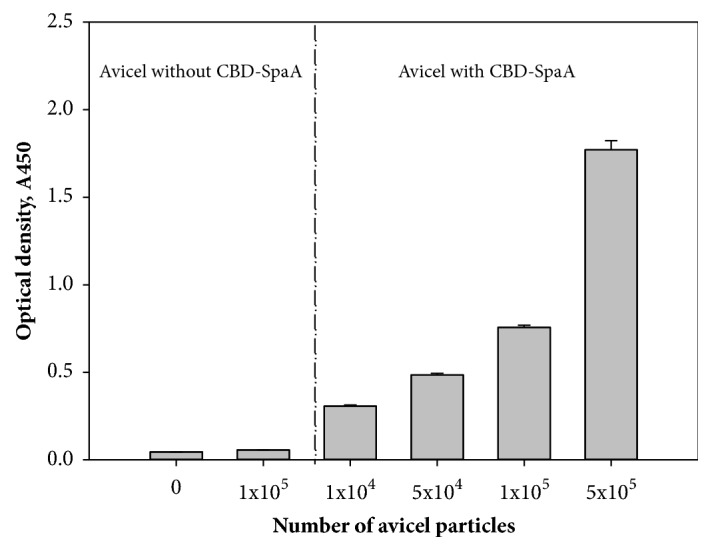

The antigenicity of CBD-SpaA bound to Avicel was evaluated by indirect ELISA assay. As shown in Figure 4, the increased absorbance values were detected in proportion to the number of Avicel particles coated with CBD-SpaA, whereas the Avicel without CBD-SpaA as a negative control showed a value as low as the PBS. Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) was used for visualization of antigenic properties of the Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA (Figure 5). Purified fusion protein was bound to Avicel and incubated with anti-serum of whole E. rhusiopathiae, followed by goat-mouse IgG-FITC. CLSM images demonstrated that green fluorescence dispersed almost equally on the surface of the Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

ELISA assay of Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA (n=3).

Figure 5.

CLSM images for CBD-SpaA-H6 immobilized on Avicel. Purified CBD-SpaA protein was bound to Avicel and incubated with anti-histidine antibody followed by goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC. The confocal microscope image indicates that CBD-SpaA protein had a high binding affinity to Avicel. (a) Differential interference contrast images; (b) FITC fluorescence; (c) merging of the two split images.

3.4. Protective Immunity in Immunized Mice

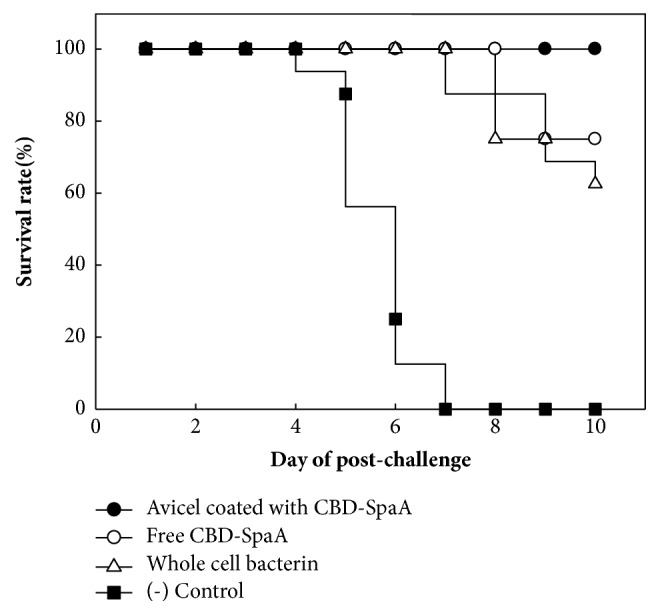

To examine whether protection could be induced without side effects by immunization with the Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA, we injected each protein (free CBD-SpaA and Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA, ERT2T-1 containing whole cell bacterin (positive control) from CVAVC in the Republic of Korea, and PBS (negative control)) into mice and challenged the mice with E. rhusiopathiae. All of the negative control mice died within seven days after challenge. Compared with negative control group, 5 of 8 (p < 0.0001, by Fisher's exact test) mice in the ERT2T-1 immunized group, and 6 of 8 (p < 0.0001, by Fisher's exact test) mice in the free CBD-SpaA immunized group, survived. In the Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA, the immunized group of mice showed 100% (p < 0.0001, by Fisher's exact test) immune-protection against challenge with E. rhusiopathiae (Figure 6). However that group did not show significant difference with the free CBD-SpaA immunized group (p = 0.467, by Fisher's exact test). These results demonstrated that the microcrystalline cellulose can be used as a delivery carrier of recombinant protein.

Figure 6.

Cumulative mortality of immunized mice after challenge. Mice were vaccinated with free CBD-SpaA, Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA, and ERT2T-A containing whole cell bacterin as a positive control and PBS as a negative control. After 14 days, all the mice were challenged with highly virulent E. rhusiopathiae and survival was monitored for ten days.

4. Discussion

Antigen subunits or synthetic peptides are considered as a promising alternative for viral vaccines. They have been also considered safer vaccine systems than killed/inactivated or live-attenuated whole cells/viruses. Recombinant DNA technology has made the development of subunit vaccines more efficient, because the production and purification procedure can be carefully designed to obtain high yields of a well-defined product [22]. However, some studies have shown that soluble immunogens rarely induce high titers of antibodies without the use of strong adjuvants [23, 24]. To overcome the typical low immunogenicity of protein-based vaccines, and to address the need for effective vaccines and efficient delivery systems, researchers have moved in the direction of molecular biotechnology [25]. Recently, advances in recombinant biotechnology have led to the development of genetically engineered polymers with exact order and accuracy of amino acid residues. Recombinant protein-based polymers such as elastin-like polymers (ELPs), silk-like polymers (SLPs), and silk-elastin-like protein polymers (SELPs) have been reported to bring controlled release, longer circulating therapeutics, and tissue-specific treatment options [26]. Nanoscale structures such as gold nanoparticles and virus-like particles have also recently peaked interests for drug delivery as they offer manifest benefits [27, 28].

In our study, Avicel was selected as immunosorbent for purification and delivery of recombinant protein subunit vaccine, because it is highly inert, inexpensive, and safe biomaterial. This should protect the protein subunit vaccine from degradation in harsh conditions (extreme pH or temperature). As shown in Figure 4, immune response increased with increasing Avicel particle concentration, confirming its suitability as a better immunosorbent for vaccine systems. The higher immunity achieved with increased Avicel concentration could be due to selective coating of SpaA by Avicel.

Our findings clearly demonstrate that Avicel is specific for the CBD-SpaA with good binding capacity for vaccine delivery. The binding capacity was visualized using CLSM imaging as shown in Figure 5. It has been well known that the Spa proteins are potent protective antigens against E. rhusiopathiae infection [29]. Recent reports show that SpaA is the major Spa-type of serotypes 1a, 1b, and 2 [30] which are most commonly implicated in swine erysipelas. The protective domain of SpaA lies between amino acids 29-414 [30]. This particular amino acid sequence itself can induce highly protective antibodies against E. rhusiopathiae infection [15]. Being a well delivery agent and immune sorbent, Avicel further enhanced its potency as we found in our experiments.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we developed a vaccine using microcrystalline cellulose, Avicel PH-101 to deliver recombinant protein-based antigen against erysipelas. The recombinant protein, CBD-SpaA, was expressed in E. coli and bound to Avicel PH-101. Our data perceptibly showed that a 100% survival rate could be achieved using the Avicel coated with antigen in E. rhusiopathiae-challenged mice. Thus, the in vitro immunogenicity test has been validated by the in vivo challenge experiment.

In our newly developed vaccine system, protein purification is unnecessary. This cuts down production costs and enables a cost-effective, recombinant protein vaccine system. Specifically, our delivery system using Avicel coated with CBD-SpaA could provide an appealing vaccination strategy against erysipelas.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from KRIBB Research Initiative Program. This work was supported by the Advanced Biomass R&D Center (ABC) of the Global Frontier Project funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (ABC-2015M3A6A2074238).

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Wooyoung Jeon and Yeu-Chun Kim contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Saroja C., Lakshmi P., Bhaskaran S. Recent trends in vaccine delivery systems: A review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation. 2011;1(2):64–74. doi: 10.4103/2230-973X.82384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiou C.-J., Tseng L.-P., Deng M.-C., et al. Mucoadhesive liposomes for intranasal immunization with an avian influenza virus vaccine in chickens. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5862–5868. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moser C., Amacker M., Kammer A. R., Rasi S., Westerfeld N., Zurbriggen R. Influenza virosomes as a combined vaccine carrier and adjuvant system for prophylactic and therapeutic immunizations. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2007;6(5):711–721. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy S. T., van der Vlies A. J., Simeoni E., et al. Exploiting lymphatic transport and complement activation in nanoparticle vaccines. Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25(10):1159–1164. doi: 10.1038/nbt1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C., Ge Q., Ting D., et al. Molecularly engineered poly(ortho ester) microspheres for enhanced delivery of DNA vaccines. Nature Materials. 2004;3:190–196. doi: 10.1038/nmat1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansson M., Nygren P.-A., Stahl S. Design and production of recombinant subunit vaccines. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry. 2000;32(2):95–107. doi: 10.1042/BA20000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liljeqvist S., Stahl S. Production of recombinant subunit vaccines: Protein immunogens, live delivery systems and nucleic acid vaccines. Journal of Biotechnology. 1999;73(1):1–33. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(99)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunin V. G., Sharapova N. E., Tikhonova T. V., et al. Research into the immunogenic properties of the recombinant cellulose-binding domain of Anaerocellum thermophilum in vivo. Molekuliarnaia Genetika, Mikrobiologiia I Virusologiia. 2009:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKee A. S., Munks M. W., Marrack P. How do adjuvants work? Important considerations for new generation adjuvants. Immunity. 2007;27(5):687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgiou G., Stathopoulos C., Daugherty P. S., Nayak A. R., Iverson B. L., Curtiss R. Display of heterologous proteins on the surface of microorganisms: From the screening of combinatorial libraries to live recombinant vaccines. Nature Biotechnology. 1997;15(1):29–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt0197-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klemm D., Heublein B., Fink H. P., Bohn A. Cellulose: fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angewandte Chemie. 2005;44(22):3358–3393. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linder M., Teeri T. T. The roles and function of cellulose-binding domains. Journal of Biotechnology. 1997;57(1–3):15–28. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurice S., Dekel M., Shoseyov O., Gertler A. Cellulose beads bound to cellulose binding domain-fused recombinant proteins; an adjuvant system for parenteral vaccination of fish. Vaccine. 2003;21(23):3200–3207. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimoji Y. Pathogenicity of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: Virulence factors and protective immunity. Microbes and Infection. 2000;2(8):965–972. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00397-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imada Y., Goji N., Ishikawa H., Kishima M., Sekizaki T. Truncated surface protective antigen (SpaA) of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae serotype 1a elicits protection against challenge with serotypes 1a and 2b in pigs. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(9):4376–4382. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4376-4382.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheun H. I., Kawamoto K., Hiramatsu M., et al. Protective immunity of SpaA-antigen producing Lactococcus lactis against Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae infection. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2004;96(6):1347–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimoji Y., Mori Y., Fischetti V. A. Immunological characterization of a protective antigen of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: Identification of the region responsible for protective immunity. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(4):1646–1651. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1646-1651.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eamens G. J., Chin J. C., Turner B., Barchia I. Evaluation of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae vaccines in pigs by intradermal challenge and immune responses. Veterinary Microbiology. 2006;116(1-3):138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santiago-Hernández J. A., Vásquez-Bahena J. M., Calixto-Romo M. A., et al. Direct immobilization of a recombinant invertase to Avicel by E. coli overexpression of a fusion protein containing the extracellular invertase from Zymomonas mobilis and the carbohydrate-binding domain CBDCex from Cellulomonas fimi. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2006;40(1):172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.10.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong F., Meinander N. Q., Jönsson L. J. Fermentation strategies for improved heterologous expression of laccase in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2002;79(4):438–449. doi: 10.1002/bit.10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn J. O., Choi E. S., Lee H. W., et al. Enhanced secretion of Bacillus stearothermophilus L1 lipase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by translational fusion to cellulose-binding domain. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2004;64(6):833–839. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersson C. Production and Delivery of Recombinant Subunit Vaccines. Department of Biotechnology. Royal Institute of Technology (KTH); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez O., Batista-Duharte A., González E., et al. Human prophylactic vaccine adjuvants and their determinant role in new vaccine formulations. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2012;45(8):681–692. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S., Liu H., Zhang X., Qian F. Intranasal and oral vaccination with protein-based antigens: Advantages, challenges and formulation strategies. Protein & Cell. 2015;6(7):480–503. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0164-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nascimento I. P., Leite L. C. C. Recombinant vaccines and the development of new vaccine strategies. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2012;45(12):1102–1111. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frandsen J. L., Ghandehari H. Recombinant protein-based polymers for advanced drug delivery. Chemical Society Reviews. 2012;41(7):2696–2706. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15303c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong F. Y., Zhang J. W., Li R. F., Wang Z. X., Wang W. J., Wang W. Unique roles of gold nanoparticles in drug delivery, targeting and imaging applications. Molecules. 2017;22(9):p. 1445. doi: 10.3390/molecules22091445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill B. D., Zak A., Khera E., Wen F. Engineering virus-like particles for antigen and drug delivery. Current Protein & Peptide Science. 2018;19(1):112–127. doi: 10.2174/1389203718666161122113041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galan J. E., Timoney J. F. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a protective antigen of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. Infection and Immunity. 1990;58(9):3116–3121. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3116-3121.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.To H., Nagai S. Genetic and antigenic diversity of the surface protective antigen proteins of Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2007;14(7):813–820. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00099-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.