ABSTRACT

Side chain-containing steroids are ubiquitous constituents of biological membranes that are persistent to biodegradation. Aerobic, steroid-degrading bacteria employ oxygenases for isoprenoid side chain and tetracyclic steran ring cleavage. In contrast, a Mo-containing steroid C-25 dehydrogenase (S25DH) of the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) reductase family catalyzes the oxygen-independent hydroxylation of tertiary C-25 in the anaerobic, cholesterol-degrading bacterium Sterolibacterium denitrificans. Its genome contains eight paralogous genes encoding active site α-subunits of putative S25DH-like proteins. The difficult enrichment of labile, oxygen-sensitive S25DH from the wild-type bacteria and the inability of its active heterologous production have largely hampered the study of S25DH-like gene products. Here we established a heterologous expression platform for the three structural genes of S25DH subunits together with an essential chaperone in the denitrifying betaproteobacterium Thauera aromatica K172. Using this system, S25DH1 and three isoenzymes (S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4) were overproduced in a soluble, active form allowing a straightforward purification of nontagged αβγ complexes. All S25DHs contained molybdenum, four [4Fe-4S] clusters, one [3Fe-4S] cluster, and heme B and catalyzed the specific, water-dependent C-25 hydroxylations of various 4-en-3-one forms of phytosterols and zoosterols. Crude extracts from T. aromatica expressing genes encoding S25DH1 catalyzed the hydroxylation of vitamin D3 (VD3) to the clinically relevant 25-OH-VD3 with >95% yield at a rate 6.5-fold higher than that of wild-type bacterial extracts; the specific activity of recombinant S25DH1 was twofold higher than that of wild-type enzyme. These results demonstrate the potential application of the established expression platform for 25-OH-VD3 synthesis and pave the way for the characterization of previously genetically inaccessible S25DH-like Mo enzymes of the DMSO reductase family.

KEYWORDS: alkyl hydroxylases, anaerobic catabolic pathways, molybdenum enzymes, sterols, vitamin D3 biosynthesis

IMPORTANCE

Steroids are ubiquitous bioactive compounds, some of which are considered an emerging class of micropollutants. Their degradation by microorganisms is the major process of steroid elimination from the environment. While oxygenase-dependent steroid degradation in aerobes has been studied for more than 40 years, initial insights into the anoxic steroid degradation have only recently been obtained. Molybdenum-dependent steroid C-25 dehydrogenases (S25DHs) have been proposed to catalyze oxygen-independent side chain hydroxylations of globally abundant zoo-, phyto-, and mycosterols; however, so far, their lability has allowed only the initial characterization of a single S25DH. Here we report on a heterologous gene expression platform that allowed for easy isolation and characterization of four highly active S25DH isoenzymes. The results obtained demonstrate the key role of S25DHs during anoxic degradation of various steroids. Moreover, the platform is valuable for the efficient enzymatic hydroxylation of vitamin D3 to its clinically relevant C-25-OH form.

INTRODUCTION

Steroids are a ubiquitously occurring class of highly hydrophobic compounds that in eukaryotes act as hormones and essential components of biological membranes (1, 2). Due to their wide abundance and biological activity, the elimination of steroids from the environment is of global relevance (3, 4). Biodegradation of steroids is hampered by their low water solubility and by the complex tetracyclic core structure comprising quaternary carbon atoms. Only microorganisms are capable of fully degrading steroids to CO2. In the presence of oxygen, degradation of steroids heavily depends on oxygenase-dependent hydroxylation and ring cleavage reactions (5, 6).

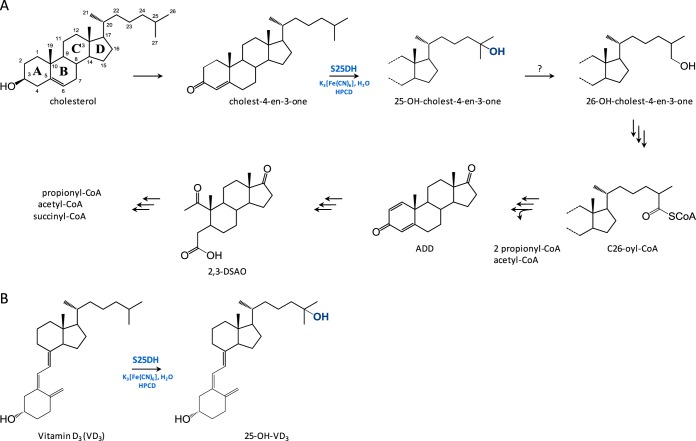

Anaerobic steroid degradation has been studied in only a few denitrifying proteobacteria with the cholesterol-degrading Sterolibacterium denitrificans serving as a model organism (7). Recent studies revealed a patchwork pathway for anaerobic steroid degradation (8, 9). As in aerobic cholesterol-degrading organisms, cholest-4-en-3-one is formed as the first intermediate from cholesterol in S. denitrificans (Fig. 1A) (10). The subsequent hydroxylation of the side chain with water that occurs at tertiary C-25 is then catalyzed by molybdenum (Mo)-dependent steroid C-25 dehydrogenase (S25DH) (10, 11), and not at primary C-26 as observed in the oxygenase-dependent pathway. The next step involves a formal shift of the hydroxyl group from the tertiary C-25 to primary C-26 by an unknown enzyme (8, 12). Further degradation to androsta-1,4-diene-3,17-dione (ADD) proceeds via oxidation and activation to a C-26-oyl-coenzyme A (CoA) component, followed by modified β-oxidation like reaction sequences (Fig. 1) (8, 13). Finally, cleavage of the steran rings A and B proceeds in the so-called 2,3-seco-pathway involving ring-cleaving hydrolases (14, 15); degradation of rings C and D appears to be similar in aerobic and anaerobic steroid-degrading bacteria, again using hydrolytic enzymes (Fig. 1) (16).

FIG 1 .

(A) Proposed anoxic degradation pathway of cholesterol in Sterolibacterium denitrificans. The activation of the side chain is mediated by S25DH, which hydroxylates the tertiary C-25 carbon with water. ADD, androsta-1,4-diene-3-one; 2,3-DSAO, 1,17-dioxo-2,3-seco-androstan-3-oic acid. (B) Conversion of vitamin D3 (VD3) to 25-OH-VD3 by S25DH using ferricyanide as the electron acceptor.

A S25DH was initially isolated and characterized by Dermer and Fuchs (11) as a molybdenum cofactor (MoCo)-containing enzyme of the dimethyl sulfoxide reductase (DMSOR) family of Mo enzymes. The enzyme has an αβγ architecture comprising a 108-kDa (α), 38-kDa (β), and 23-kDa (γ) subunit. The catalytically active α-subunit contains a molybdo-bis-pyranopterin guanine dinucleotide (Mo-bisPGD) cofactor and a [4Fe-4S] cluster; the β-subunit harbors four additional FeS clusters, and the γ-subunit contains a b-type heme. Like other members of the DMSOR family, S25DH is proposed to be located in the periplasm. It was proposed that a chaperone (SdhD) is involved in proper folding and probably in MoCo insertion (11). S25DH together with ethylbenzene dehydrogenase (EbDH) (17, 18) and p-cymene dehydrogenase (19) forms a phylogenetic subcluster within class II of the DMSOR family, that hydroxylate alkyl side chains of steroids or aromatic compounds with water (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (20). Attempts for heterologous/homologous production of S25DH/EbDH subclass members have failed so far (21), which prevented an easy enrichment procedure, as well as the generation of molecular variants.

Phylogenetic tree of active site α-subunits from S25DH-like enzymes inside the DMSOR family of MoCo-containing enzymes. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.5 MB (558.2KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

A recent study revealed that S25DH is capable of hydroxylating vitamin D3 (VD3) to the clinically relevant 25-OH-VD3 (Fig. 1B) (22). This activity was dependent on 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin that is known to promote the isomerization to pre-VD3 (23), the assumed actual substrate of S25DH. In contrast to cytochrome P450-dependent hydroxylation of VD3, S25DH-dependent catalysis is independent of an electron donor system and requires only the electrochemically regenerative K3[Fe(CN)6] (ferricyanide) as an electron acceptor (22). Though S25DH serves as a promising catalyst for the synthesis of 25-OH-VD3, there is a high demand for heterologous expression and for improving the enrichment of S25DH-like enzymes with regard to activities and stabilities.

Sterolibacterium denitrificans is capable of degrading phyto- and mycosterols such as β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, or ergosterol with modifications in the isoprenoid side chain (for structures, see Table 1), but the only cholest-4-en-3-one-converting S25DH studied so far is unable to convert any of the 4-en-3-one analogues of these growth substrates (8, 11). In addition to the gene encoding the active site α-subunit of this S25DH (henceforth referred to as α1 subunit of S25DH1, gene accession number SDENCHOL_20805), the genome contains seven paralogous genes encoding putative S25DH-like enzymes, all affiliating with the class II DMSOR family (α2-α8) (8, 11). In particular, the predicted active site α2–4 (amino sequence identities to α1 of 72 to 82%) have been hypothesized to represent the active site subunits of S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4 involved in C-25 hydroxylation of steroids with modified isoprenoid side chains (Fig. 2A). This assumption is based on their differential abundance during growth on different steroids such as β-sitosterol or ergosterol (8); the role of the other four putative S25DHs (S25DH5, S25DH6, S25DH7, and S25DH8) is unclear (8). Notably, there are fewer genes encoding the βγ-subunit components than for the α-subunits in the genome of S. denitrificans (Fig. 2A), suggesting that S25DHs with different α-subunits share common βγ-subunit components. S25DH1 from S. denitrificans is composed of the α1β3γ3-subunits (Fig. 2A). Enriched S25DH1 always contained impurities of other α-subunits, which made a clear assignment of activities to individual α-subunits problematic (11, 22).

TABLE 1 .

Relative activities of S25DH1 in cell extracts of Sterolibacterium denitrificans cells grown with cholesterol compared to those in cell extracts from T. aromatica producing S25DH1, S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4

aStructural differences are shown in red.

bOne hundred percent activity corresponds to 1.87 nmol min−1 mg−1 as observed for cholest-4-en-3-one conversion by extracts from wild-type bacteria grown with cholesterol. The boldface values indicate activities higher than 100%.

FIG 2 .

Genes encoding S25DH subunits and chaperone. (A) Arrangement of genes encoding putative α1-4 (MoCo-containing), β3,4 (4Fe-4S cluster-containing), and γ3,4 (heme b-containing) subunits, as well as the chaperone (SdhD) of S25DHs. (B) Constructs prepared for the heterologous production of S25DH1, S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4.

In this work, we aimed to elucidate the unknown function of Mo-containing S25DH isoenzymes in S. denitrificans in anaerobic steroid degradation and to explore their potential use for 25-OH-VD3 synthesis. For this purpose, an expression platform for S25DH and related enzymes was established in the denitrifying betaproteobacterium Thauera aromatica yielding S25DHs with high yields and specific activities. With this tool, four recombinant S25DHs were isolated and characterized; their applicability as catalysts for 25-OH-VD3 synthesis was probed.

RESULTS

Heterologous production of S25DH1.

The previously established five-step enrichment of the oxygen-sensitive S25DH1 (α1β3γ3 complex) from wild-type Sterolibacterium denitrificans grown with cholesterol always gave low yields, low specific activities, and a partially degraded α1-subunit (11, 22, 24). Moreover, the enriched enzyme frequently contained impurities from other S25DH α-subunits next to the α1-subunit, which did not allow unambiguous assignment of activities to individual gene products (11, 22). These findings motivated us to establish a platform for actively expressing the genes encoding S25DH1 and related enzymes. For this reason, the genes encoding the α1β3γ3-subunits, together with the putative chaperone (henceforth referred to as SdhD) (Fig. 2) were cloned into the broad-host-range plasmid pIZ1016. This construct contained the twin-arginine translocation (TAT) secretion sequence at the N terminus of the α1-subunit; to avoid any possible negative effect on αβγ complex formation, we avoided the use of a tagged subunit. Heterologous production of the resulting α1β3γ3SdhD construct was tested in Escherichia coli strains BL21 and Top 10, Azoarcus sp. strain CIB, and Thauera aromatica K172.

Heterologous production of the α1-subunit alone in the presence or absence of SdhD was not monitored in this work, as preliminary experiments indicated that such constructs did not result in the formation of soluble/active proteins. Expression of the α1β3γ3SdhD-encoding genes did not give soluble gene products in either of the two E. coli strains, and consequently, virtually no formation of 25-hydroxy-cholest-4-en-3-one was observed. However, after heterologous production of α1β3γ3SdhD in Azoarcus sp. CIB (25) and T. aromatica (26), anaerobically prepared cell extracts from both species showed the conversion of 0.5 mM cholest-4-en-3-one (0.5 mM) to 25-hydroxy-cholest-4-en-3-one; this conversion was dependent on time, protein, K3[Fe(CN)6] (5 mM), and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPCD) (9% wt/vol) and was observed only with constructs containing all four α1β3γ3SdhD components. The specific activities of recombinant S25DH1 were maximally 3.3 nmol min−1 mg−1 in cell extracts from Azoarcus sp. CIB and 12 nmol min−1 mg−1 in cell extracts from T. aromatica. Remarkably, both specific activities were 176% and more than 640% of the activity in cell extracts of cholesterol-grown S. denitrificans (1.87 nmol min−1 mg−1), respectively, demonstrating overproduction of S25DH1 in the Azoarcus and Thauera species (Table 1). Under anoxic conditions, loss of recombinant S25DH1 activity was less than 10% for 1 week at 4°C. In the presence of 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], activity in T. aromatica crude extracts was stable in air at 30°C for 5 to 8 h but decreased to 50% after 24 h.

T. aromatica crude extracts producing S25DH1 catalyzed the conversion of VD3 to 25-OH-VD3 at 2.8 nmol min−1 mg−1 that was 6.5-fold higher compared to wild-type extract (0.43 nmol min−1 mg−1). This increased VD3 conversion rate shortened the conversion of 1 mM VD3 correspondingly (90% conversion in 2 h by 12 mg ml−1 crude extracts) (Fig. 3), allowing 25-OH-VD3 synthesis even in air without loss of activity. The absence of 25-OH-VD3-converting enzymes in T. aromatica made the addition of AgNO3 for blocking follow-up enzymes of the cholesterol degradation pathway dispensable (22). Recombinant S25DH also converted 7-dehydrocholesterol to its 25-OH form, as had also been reported for the wild-type enzyme (11); no analogues with modifications in the isoprenoid side chain were converted (Table 1).

FIG 3 .

Aerobic conversion of 1 mM VD3 to 25-OH-VD3 by crude extracts of Thauera aromatica K172 producing S25DH1 (12 mg ml−1). Symbols: ● VD3; ▲, 25-OH-VD3.

Heterologous production of S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4 isoenzymes in T. aromatica.

The results obtained indicated that T. aromatica K172 represents the most suitable host for the heterologous production of S25DH-like enzymes. For this reason, we used this strain for the production of three additional S25DH-like proteins that contain the α2-4 active site subunits, respectively. The constructs were cloned into pIZ1016 in a manner to give S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4 with the compositions α2β3γ3, α3β3γ3, and α4β4γ4 referred to as S25DH2, S25DH3 and S25DH4 (Fig. 2). Notably, the β3γ3 and β4γ4 subunits are almost identical (99% sequence identity), and the coexpression of their genes with those encoding individual α-subunits was chosen to facilitate the cloning procedure. In all cases, SdhD was coproduced with the individual S25DH isoenzymes.

Using cell extracts from T. aromatica producing the individual S25DH-like gene products, we tested the conversion of cholest-4-en-3-one, 7-dehydrocholesterol, vitamin D3, campest-4-en-3-one, brassica-4-en-3-one, ergosterol, β-sitost-4-en-3-one, and stigmast-4-en-3-one as possible substrates. The time-dependent formation of products was analyzed by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) separation coupled to diode array detection; identification was by UPLC coelution with standards in addition to electrospray ionization quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (ESI-QTOF-MS) detection. For UPLC chromatograms of conversions, see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material; for relative specific activities, see Table 1.

UPLC chromatograms showing the conversion of various steroid substrates by different recombinant S25DHs from Sterolibacterium denitrificans heterologously produced in T. aromatica. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.2 MB (229.9KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Using cell extracts of T. aromatica producing S25DH2, the rate of 25-OH-7-dehydrocholesterol formation was slightly higher than conversion of cholest-4-en-3-one. This extract converted VD3 to 25-OH-VD3 at a higher rate than S. denitrificans extracts grown with cholesterol, albeit the activity was only around 20% of recombinant S25DH1 (Table 1). Previous differential proteome analysis showed that the α3-subunit of an S25DH (SDENCHOL_20460) was most abundant during growth with ergosterol containing a Δ22 double bond in the side chain (8). Unexpectedly, T. aromatica expressing the S25DH3 formed only traces of 25-OH-ergosterol from ergosterol. Likewise, brassica-4-en-3-one, an ergosterol analogue with AB rings identical to those in cholest-4-en-3-one was virtually not converted. Surprisingly, campest-4-en-3-one, which lacks the double bond in the side chain but contains an additional methyl branch at (R)-configured C-24, was the only steroid substrate tested that was converted by S25DH3 to its 25-OH-form in significant amounts (Table 1). The α4-subunit was found upregulated in S. denitrificans cells grown with β-sitosterol, a cholesterol analogue with an additional ethyl branch at C-24 (8). In full agreement, T. aromatica cell extracts producing S25DH4 converted β-sitost-4-en-3-one and the structurally related campest-4-en-3-one, both with an (R)-configured tertiary C-24; cholest-4-en-3-one lacking an additional alkyl substituent at this position was also converted at a slightly higher rate (Table 1).

Enrichment, activity, and composition of recombinant S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4.

The results obtained so far indicated a higher heterologous production of S25DH1 and probably other S25DHs in Azoarcus sp. CIB and T. aromatica K172 than in wild-type S. denitrificans. As a result, only two out of five chromatographic enrichment steps described for purification from the wild-type bacteria were necessary. The two steps were DEAE anion-exchange chromatography and affinity chromatography on Reactive Red agarose (11, 22); we initially tested the purification of the recombinant S25DH1 from both strains.

With Azoarcus sp. CIB extracts, five protein bands were obtained after the two-step purification procedure (Fig. S3). The bands migrating at 110, 40, and 25 kDa were clearly assigned to the α1β3γ3-subunits, whereas those migrating between 50 and 55 kDa represent truncated α1 degradation products, as observed during purification from S. denitrificans (11, 22). The two degradation products were estimated to make more than 80% of the total amount of the α1-subunit. This finding suggests that expression in Azoarcus sp. CIB produced predominantly degraded S25DH1 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

SDS-PAGE (12.5%) of the active fractions obtained during enrichment of S25DH1 (α1β3γ3-subunits) in Azoarcus sp. strain CIB. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 0.2 MB (181.7KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Purification of S25DH1 from T. aromatica extracts revealed a highly enriched (purity >95%) α1β3γ3 complex with an almost perfect 1:1:1 ratio of the three subunits (Fig. 4). ESI-QTOF-MS analysis of tryptic digestion products of the three excised protein bands identified the expected α1β3γ3 subunits (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Most importantly, when prepared from T. aromatica K172, α1-degradation products were negligible. These findings explain why the specific activity of recombinant S25DH1 in Azoarcus sp. CIB extracts was—though still higher than in S. denitrificans—significantly lower than in T. aromatica.

FIG 4 .

Enrichment of recombinant S25DHs. SDS-PAGE analysis of S25DH activity-containing fractions during the enrichment of recombinant S25DH1, S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4 from T. aromatica cell extracts. Lane 1; 20 µg supernatant after centrifugation at 150,000 × g; lane 2, 10 µg protein after DEAE-Sepharose chromatography; lane 3, 5 µg protein obtained after Reactive Red chromatography. The positions of the corresponding α-, β- and γ-subunits of S25DHs are indicated by arrows to the right of the S25DH4 gel. The positions of molecular size markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated to the left of the gels.

Mass spectrometric analysis of S25DH1 from S. denitrificans heterologously produced in T. aromatica K172. Download TABLE S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.7KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Based on the results obtained with S25DH1, the S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4 isoenzymes were similarly purified after production of the individual enzymes in T. aromatica. During purification of the three S25DHs, the activity-containing fractions were assayed with the following substrates: cholest-4-en-3-one (S25DH2 and S25DH4) and campest-4-en-3-one (S25DH3). In all cases, predominantly nondegraded S25DH complexes were produced; only with S25DH2 a minor formation of α2-degradation products (<10%) was observed, as evidenced by a double band around 50 to 55 kDa (Fig. 4). The specific activities determined were highest with S25DH1/cholest-4-en-3-one (395 nmol min−1 mg−1); the enrichment factors varied between 15-fold (S25DH4) and 38-fold (S25DH1) with yields between 27 and 38% (Table 2).

TABLE 2 .

Enrichment of four S25DHs starting from 5 g (wet weight) recombinant T. aromatica

| Enzyme and fraction | Protein (mg) |

Sp act (nmol min−1 mg−1)a |

Enrichment factor |

Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S25DH1 | ||||

| Soluble fraction | 645 | 11.2 | 100 | |

| DEAE + Reactive Red | 6.6 | 395 | 35.3 | 36 |

| S25DH2 | ||||

| Soluble fraction | 546 | 9.3 | 100 | |

| DEAE + Reactive Red | 9 | 151 | 16.2 | 27 |

| S25DH3 | ||||

| Soluble fraction | 590 | 0.21 | 100 | |

| DEAE + Reactive Red | 10.2 | 4.6 | 21.9 | 38 |

| S25DH4 | ||||

| Soluble fraction | 552 | 6.4 | 100 | |

| DEAE + Reactive Red | 10 | 97 | 15.1 | 27 |

Specific activities were determined by the conversion of cholest-4-en-3-one for S25DH1, S25DH2, and S25DH4 and of campest-4-en-3-one for S25DH3.

The subunit architecture and native molecular masses of the S25DHs were determined by size exclusion chromatography as follows: 167 ± 5 kDa for S25DH, S25DH2, and S25DH3 and 160 ± 5 kDa for S25DH4. These values clearly point to an αβγ composition of all four heterologously produced S25DHs.

Metal content of recombinant S25DHs.

On the basis of the results of previous metal analyses with wild-type S25DH1 enzyme and on the conserved binding motifs of the individual cofactors, the purified recombinant S25DH1, S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4 were expected to bind a Mo-bisPGD, four [4Fe-4S] clusters, one [3Fe-4S] cluster, and a heme b, giving one Mo atom and 20 Fe atoms per αβγ trimer, respectively (11). The Fe content was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES), and the Mo content was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS). The metal content of the four S25DHs varied between 0.5 and 0.8 Mo atoms and between 13.2 and 15.3 Fe atoms per αβγ trimer, which is in the range of the values determined for the wild-type enzyme (0.7 Mo atom and 16.5 Fe atoms per enzyme) (11) (Table 3).

TABLE 3 .

Kinetic parameters and metal content of heterologously produced S25DH1, S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4

| Enzyme and substrate | Km (mM)a,b | kcat (s−1)a,b |

kcat/Km (103 M–1 s−1)a |

Mo contentb,c | Fe contentb,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S25DH1 | |||||

| Cholest-4-en-3-one | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 1.11 ± 0.08 | 2.8 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 15.3 ± 0.5 |

| Vitamin D3 | 0.29 ± 0.09 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.79 | ||

| S25DH2 | |||||

| Cholest-4-en-3-one | 0.124 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 2.3 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 13.5 ± 0.8 |

| 7-Dehydrocholesterol | 0.123 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 2.7 | ||

| S25DH3 | |||||

| Campest-4-en-3-one | 1.84 ± 0.8 | 0.018 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 14.2 ± 0.5 |

| S25DH4 | |||||

| Cholest-4-en-3-one | 0.45 ± 0.013 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 13.2 ± 0.4 |

| Campest-4-en-3-one | 0.34 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.50 | ||

| β-Sitost-4-en-3-one | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.003 | 1.2 |

Kinetic parameters were determined by UPLC-based enzyme assays using different concentrations of the respective substrates in the presence of 9% (wt/vol) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin.

Mean values ± standard deviations of three biological replicates are given.

Fe content was measured by ICP-AES, and Mo content was measured by ICP-MS. The number of Mo or Fe atoms per protein is given.

Kinetic parameters of recombinant S25DH1, S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4.

The Km and kcat values of each recombinant S25DH were determined using their individual preferred substrates. Notably, the Km values determined have to be regarded as apparent values, as the nearly insoluble steroid substrates were converted only in the presence of high concentrations of the solubilizing 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (9%, wt/vol). The kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 3 with S25DH1, S25DH2, and S25DH4 showing the highest kcat/Km values for cholest-4-en-3-one, 7-dehydrocholesterol, and β-sitost-4-en-3-one, respectively, suggesting that the respective steroids do indeed represent the preferred substrates. In the case of S25DH3, the low catalytic number together with the high Km determined for campest-4-en-3-one indicates that the enzyme is specific for a so far unknown steroid, with campest-4-en-3-one representing the only analogue that is converted to some extent.

Enrichment and characterization of S25DH4 from S. denitrificans grown with β-sitosterol.

To ascertain whether S25DH4 has an extended substrate spectrum toward β-sitost-4-en-3-one and campest-4-en-3-one, it was isolated from the wild-type bacteria. For this purpose, S. denitrificans was grown in a 200-liter fermenter with 3 mM β-sitosterol in a fed-batch culture, yielding 184 g cells (wet weight) (Fig. S4). Cell extracts of S. denitrificans grown with β-sitosterol converted β-sitost-4-en-3-one to the corresponding 25-OH-form at a specific activity of 0.6 nmol min−1 mg−1 (17% of the activity in recombinant T. aromatica).

Growth of S. denitrificans in a 200-liter fermenter with 3 mM β-sitosterol under denitrifying conditions. Download FIG S4, PDF file, 0.2 MB (160.7KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

The enrichment of β-sitost-4-en-3-one hydroxylating activity from S. denitrificans was based on the protocol described for S25DH1 with slight modifications (see Materials and Methods). After four chromatographic steps, five dominant protein bands were found; during SDS-PAGE, these bands eluted at 110, 55, 50, 37, and 27 kDa (Fig. 5). ESI-QTOF-MS analyses of tryptic digests identified SDENCHOL_20206 (110-, 55-, and 50-kDa bands), SDENCHOL_20205 (37-kDa band), and SDENCHOL_20204 (27-kDa band) (Table S2). This result indicates that the 50/55-kDa bands represent degradation subunits of the α4-subunit. Size exclusion chromatography of wild-type S25DH4 revealed the same values as determined for the nontagged recombinant enzyme produced in T. aromatica K172, suggesting an α4β4γ4 composition.

FIG 5 .

Enrichment of β-sitost-4-en-3-one converting S25DH4 from S. denitrificans grown with β-sitosterol and nitrate. Separation of protein fractions forming 25-OH-β-sitost-4-en-3-one by 12.5% SDS-PAGE after ultracentrifugation (16 µg of cell extract of supernatant) (UZ), chromatography on DEAE-Sepharose (24 µg protein) (DEAE), Q-Sepharose (24 µg protein) (Q), Reactive Red-agarose (20 µg) (RR), and Cibacron blue-agarose (10 µg) (CB). The arrows point to the protein bands that were identified as α4β4γ4 of S25DH4; the proteins migrating at 50 and 55 kDa were identified as degradation products of the α4-subunit [α4 (d1) and α4 (d2)]. Lane M contains molecular size markers (in kilodaltons).

Mass spectrometric analysis of enriched protein from wild-type S. denitrificans catalyzing β-sitost-4-en-3-one C-25 hydroxylation. Download TABLE S2, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.9KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

S25DH4 was 55-fold enriched from S. denitrificans with a maximal specific activity for β-sitost-4-en-3-one conversion of 33 nmol min−1 mg−1. Both wild-type and recombinant S25DH4 exhibited the identical substrate preference and converted β-sitost-4-en-3-one, cholest-4-en-3-one, and campest-4-en-3-one (Table 3). In summary, the S25DH4 composed of the α4β4γ4 subunits has an extended substrate specificity for β-sitost-4-en-3-one (and campest-4-en-3-one); as shown for S25DH1, the specific activity of S25DH4 in cell extracts was around sixfold higher when heterologously produced in T. aromatica compared to the wild-type S25DH4.

DISCUSSION

So far, a number of DMSOR family members have been produced by homologously or heterologously expressing their corresponding genes (27–34). In contrast, attempts to produce the phylogenetically related, complex heterotrimeric molybdenum-iron-sulfur/heme b-containing alkyl chain hydroxylases of the class II DMSOR family in an active form have failed so far. In this work we now provide a tool for their recombinant production in highly active forms as demonstrated for the example of four S25DH isoenzymes with differing substrate specificities. The expression platform opens the door for studying other alkyl chain-hydroxylating members of the DMSOR family comprising enzymes specifically forming tertiary (S25DHs), secondary (ethylbenzene DH) (17, 18), and primary (p-cymene DH) (19) alcohols, and many others of unknown function. Notably, production of highly active enzymes in the presence of SdhD required the expression of all three functional genes.

Production in Thauera aromatica yielded crude extract activities that in the case of S25DH1 and S25DH4 were sixfold higher than in cell extracts from the parental Sterolibacterium denitrificans after growth with the preferred substrates cholesterol (S25DH1) and β-sitosterol (S25DH4). The apparent overexpression largely facilitated and shortened the enrichment procedure by using only two chromatographic steps, which in turn greatly reduced to a minimum the generally observed degradation of the active site α-subunit. As a further advantage, the specific activities of the isolated enzymes of S25DH1 and S25DH4 were twofold higher than after purification from the wild type. Finally, while purification from the wild-type bacteria always yielded mixtures of different isoenzymes, the T. aromatica expression platform produced a preparation of a single S25DH. In summary, production in T. aromatica largely enhanced yield, specific activity, and specificity.

The results obtained now allow for the unambiguous assignment of substrate specificities to individual S25DH isoenzymes. The prototypical S25DH1, originally isolated from S. denitrificans cells grown with cholesterol (11), used cholest-4-en-3-one as the preferred substrate. The S25DH2 has an extended substrate spectrum toward 7-dehydrocholesterol and S25DH4 for the phytosterol-derived β-sitost-4-en-3-one and campest-4-en-3-one with (R)-configured ethyl and methyl branches at C-24, respectively. The function of S25DH3 appears to be less clear, as it showed only minor activity with campest-4-en-3-one indicating that the natural substrate is still at issue. None of the four S25DHs showed significant activity with sterols containing a Δ22,23 double bond in the side chain such as ergosterol, brassica-4-en-3-one, or stigmast-4-en-3-one, although ergosterol and stigmasterol are growth substrates. This finding suggests that either one of the four remaining S25DHs is involved in their conversion, or a more likely alternative is that the double bond needs to be reduced or otherwise converted prior to C-25 hydroxylation. As the abundance of S25DH3 in cells grown with ergosterol was clearly increased (8), it is likely that ergosterol is first converted to a so far unknown intermediate that then serves as the substrate for S25DH3. However, reduction of the nonactivated Δ22,23 double bond can hardly be achieved in the absence of oxygen with physiological electron donors. The function of S25DH5, S25DH6, S25DH7, and S25DH8 needs to be elucidated in the future using the system established in this work. S25DH7 has recently been proposed to be involved in the conversion of 25- to 26-OH-cholest-4-en-3-one. It is striking that the α-subunit of putative S25DH8 is more closely related to that of p-cymene dehydrogenase and to an S25DH-like enzyme from Thauera terpenica (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), suggesting that it may play a role in hydroxylating a nonsteroidal isoprenoid compound.

This work demonstrated that of the four S25DH isoenzymes investigated in this work, S25DH1 is the optimal catalyst for VD3 hydroxylation to the clinically relevant 25-OH-VD3 (22). This reaction is of considerable biotechnological potential, as it has several advantages in comparison to multistep chemical (35) or oxygenase- and electron donor-dependent 25-OH-VD3 synthesis procedures (36–40). The established expression platform overcomes previously identified limitations of S25DH-catalyzed 25-OH-VD3 synthesis, which have largely prevented biotechnological application so far. First, the easy and rapid enrichment procedure minimizes degradation of the α-subunit as always observed during purification from the wild-type strain. As a result, the specific activities of the enriched S25DHs are around twofold higher in the recombinant than in the wild-type strain. Second, S25DH1 was produced to a 6.4-fold-higher extent in T. aromatica than in the wild-type bacteria, resulting in the corresponding increase of the VD3 conversion rate in crude extracts. As a consequence, enzymatic 25-OH-VD3 synthesis by crude extracts is drastically shortened and can now be accomplished even under aerobic conditions without a significant loss of activity. Third, due to the lack of enzymes catalyzing downstream reactions of anaerobic steroid degradation in T. aromatica, the addition of AgNO3, the established inhibitor of these reactions, is now dispensable when using crude extracts for VD3 conversion.

In summary, the expression platform established in this work provides not only easy access to previously nonstudied members of the alkyl chain-hydroxylating DMSOR family members, it also allows for previously hardly achievable mechanistic studies (e.g., site-directed mutagenesis) and applied studies (25-OH-VitD3 synthesis) of a catalytically versatile class of molybdenum enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and bacterial strains.

The chemicals used were of analytic grade. Sterolibacterium denitrificans Chol-1ST (DSMZ 13999) and Thauera aromatica K172 (DSMZ 6984) were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung für Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). Azoarcus sp. strain CIB (CECT 5669) was obtained from the Spanish Type Culture Collection (Valencia, Spain), E. coli BL21(DE3) was from New England Biolabs (Frankfurt, Germany) and E. coli Top 10 was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Carlsbad, CA).

Synthesis of steroidal substrates.

Substrates for S25DHs were produced from commercially available steroid precursors (β-sitosterol, campesterol, brassicasterol, and stigmasterol) using cholesterol oxidase from Streptomyces sp. according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd.). The enzyme assays contained 50 mM Tris/PO4 buffer (pH 7.5), 9% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (wt/vol), 2.5 mM NAD+, 1 mM substrate, 2 mM MgCl2, cholesterol oxidase, and catalase. Products were extracted and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described elsewhere (11). Samples were lyophilized and diluted in 1,4-dioxane.

Culture conditions and preparation of cell extracts.

S. denitrificans was cultivated under denitrifying conditions in mineral medium with steroid substrates as described previously (7). Cells were harvested in the late exponential growth phase by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C). During large-scale cultivation with β-sitosterol (3 mM) in a 200-liter fermenter, nitrate was discontinuously added in 10 mM steps. T. aromatica K172 and Azoarcus sp. CIB expressing genes encoding S25DHs were cultivated under denitrifying conditions using a phosphate-buffered medium with benzoate as the carbon source at 30°C as described previously (41). Cells were harvested anaerobically by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C) in the late exponential phase. Frozen cells were suspended in 2 volumes of lysis buffer (wt/vol) containing 20 mM Tris/PO4 (pH 7.0), 0.1 mg DNase I, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.02% (wt/vol) Tween 20. Cells were lysed by passage through a French pressure cell at 137 MPa, solubilized for 3 h, and centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 1.5 h at 4°C. The anaerobically prepared supernatant was used for enzyme purification.

Enzyme assays.

Enzyme assays were anaerobically carried out at 30°C in 100 mM Tris/PO4 buffer (pH 7.0) with 0.5 mM steroid substrates (25 mM concentrated in 1,4-dioxane), 10 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], and 9% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (wt/vol) following substrate consumption and product formation by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) as described previously (11, 22). For the conversion of cholest-4-en-3-one with cell extracts of S. denitrificans, 0.5 mM AgNO3 were added to prevent further oxidation of the substrate.

Heterologous gene expression and S25DH production.

The genes encoding the αβγ-subunits together with the chaperone (SdhD) were amplified by PCR from S. denitrificans genomic DNA as the template, using primers suitable for T4 ligation (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Genes encoding γ3β3-subunits were amplified together by using S25DHγ3β3_for (for stands for forward) and S25DHγ3β3_rev (rev stands for reverse) primers, and the resulting 1.8-kb DNA fragment was ClaI/HindIII doubly digested; the genes encoding α1 and α3 subunits were amplified by using S25DHα1-3_for and S25DHα1-3_rev primers, generating a 2.9-kb DNA fragment that was HindIII/SpeI doubly digested. The gene encoding SdhD was amplified using SdhD_for and SdhD_rev primers, generating a 0.9-kb DNA fragment that was SpeI/XbaI doubly digested. All fragments were sequentially cloned into the broad-host-range vector pIZ1016 (Gmr, oripBBR1, Mob+, lacZα, Ptac/lacIq), a derivative of pBBR1MCS-5, bearing the tac promoter and lacIq regulatory gene from pMM40 (42), and transformed in E. coli NEB5α (New England Biolabs GmbH) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genes encoding the α4β4γ4 SdhD components of S25DH4 were amplified with specific primers suitable for Gibson assembly (Table S3) using the Gibson Assembly master mix (New England Biolabs GmbH) at 50°C for 1 h. The following steps are described for T. aromatica but were also similarly applied for Azoarcus sp. CIB. The genes were transformed into T. aromatica cells by electroporation as follows: T. aromatica was cultivated on phosphate-buffered medium (25 mM acetate) at 30°C until it reached an optical density at 578 nm (OD578) of 0.4 to 0.6, centrifuged (4,500 × g, 15 min, 4°C), and washed twice in 20% volume ice-cold 1 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer. Centrifuged cells (4,500 × g, 15 min, 4°C) were suspended in 0.5% volume ice-cold 1 mM MOPS–15% glycerol (wt/vol). Cells were immediately used for transformation at 1.7 kV (Eppendorf Eporator) and incubated in medium at 30°C for 4 h before plated on selection medium (0.8% Gelrite, 0.025% MgSO4 ⋅ 7H2O, 25 mM acetate, and 20 µg ml−1 gentamicin). Cultivation was carried out aerobically at 30°C until colonies were formed. For gene expression, cells were grown under denitrifying conditions in phosphate-buffered medium with benzoate as the carbon source (see above) supplemented with 20 µg ml−1 gentamicin. Expression of S25DH genes was fostered by adding 1 mM IPTG at an optical density of 0.7. After subsequent growth for 48 h, cells were harvested anaerobically in the late exponential phase. For gene expression of S25DH1 in E. coli BL21 and E. coli Top 10, cells were cultivated anaerobically (25 mM nitrate) at 30°C in M4 minimal medium and aerobically in 2× YT medium at 20°C complemented with 20 µg ml−1 gentamicin.

Oligonucleotide primers used for heterologous production of steroid C-25 dehydrogenases. Download TABLE S3, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Enrichment of recombinant proteins from T. aromatica.

After ultracentrifugation (150,000 × g, 1.5 h, 4°C), the soluble protein fraction was applied to a DEAE-Sepharose column under anaerobic conditions (50 ml; GE Healthcare) at 5 ml min−1 and washed with buffer A (20 mM Tris/PO4 [pH 7.0], 1 mM DTT, and 0.02% [wt/vol] Tween 20). The soluble protein fraction was eluted by increasing the amount of buffer B (20 mM Tris/PO4 [pH 7.0], 1 mM DTT, 0.02% [wt/vol] Tween 20, and 500 mM KCl) from 12% to 16%. Active fractions were concentrated (30-kDa cutoff membrane), diluted in 10 volumes of buffer C (20 mM Tris/morpholineethanesulfonic acid [MES] [pH 6.0], 1 mM DTT), and applied to a Reactive Red 120 column (50 ml; GE Healthcare) at 5 ml min−1. The active fractions were elute with an increasing gradient of buffer D from 0 to 100% (Tris/PO4 [pH 8.0], 1 mM DTT) in 20% steps. S25DH1, S25DH2, S25DH3, and S25DH4 eluted at pH values of approximately 6.5, 6.7, 7.5, and 7.8, respectively.

Purification of S25DH4 from S. denitrificans.

Soluble proteins were applied to a DEAE Sepharose column at 1.5 ml min−1 and washed with buffer A. Column-bound proteins were enriched using a stepwise gradient (10%) of buffer B from 10% to 20%. The active fraction was diluted 1:3 with buffer A and applied to a Q-Sepharose column (20 ml; GE Healthcare) at 0.5 ml min−1. The active fraction was eluted by a gradient of buffer C2 (20 mM MES/Tris [pH 6.0], 1 mM DTT, 0.02% Tween 20, and 500 mM KCl) from 10% to 20%. The active fractions were diluted in 1:10 in buffer C and applied to a Reactive Red 120 column at 0.5 ml min−1. The active fractions were eluted by increasing the concentration of buffer C2 from 80% to 100%. Activity-containing fractions were concentrated, desalted, and screened for activity. Active fractions were applied to a Cibacron blue-Sepharose column (1 ml; GE Healthcare) at 0.5 ml min−1 using buffer C. The active fractions were eluted by increasing the concentration of buffer D in 20% steps from 80% to 100%. The active fractions were pooled and concentrated (30-kDa cutoff membrane).

Determination of Mo and Fe content by ICP-MS/ICP-AES.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS)/inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) analyses were conducted to determine the Mo and Fe content of heterologously produced S25DHs as described previously (43).

Gel filtration.

The native molecular weight of steroid C-25 dehydrogenases was analyzed by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) at 0.5 ml min−1 in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0)–150 mM NaCl. Proteins used for calibration were thyroglobulin (669 kDa), apoferritin (443 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), and cytochrome c (12.4 kDa).

Protein identification by mass spectrometry.

Proteins were identified by excising the bands of interest from an SDS-PAGE. After in-gel digestion with trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich), the resulting peptides were separated by UPLC and identified by using a Synapt G2-Si high-definition mass spectrometry (HDMS) electrospray ionization quadrupole time of flight (ESI-QTOF) system (Waters) as described previously (44).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Germany Research Foundation DFG (BO 1565, 15-1) and by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain (BIO2016-79736-R).

Footnotes

Citation Jacoby C, Eipper J, Warnke M, Tiedt O, Mergelsberg M, Stärk H-J, Daus B, Martín-Moldes Z, Zamarro MT, Díaz E, Boll M. 2018. Four molybdenum-dependent steroid C-25 hydroxylases: heterologous overproduction, role in steroid degradation, and application for 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 synthesis. mBio 9:e00694-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00694-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dufourc EJ. 2008. Sterols and membrane dynamics. J Chem Biol 1:63–77. doi: 10.1007/s12154-008-0010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nes WD. 2011. Biosynthesis of cholesterol and other sterols. Chem Rev 111:6423–6451. doi: 10.1021/cr200021m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbosa MO, Moreira NFF, Ribeiro AR, Pereira MFR, Silva AMT. 2016. Occurrence and removal of organic micropollutants: an overview of the watch list of EU Decision 2015/495. Water Res 94:257–279. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ting YF, Praveena SM. 2017. Sources, mechanisms, and fate of steroid estrogens in wastewater treatment plants: a mini review. Environ Monit Assess 189:178. doi: 10.1007/s10661-017-5890-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergstrand LH, Cardenas E, Holert J, Van Hamme JD, Mohn WW. 2016. Delineation of steroid-degrading microorganisms through comparative genomic analysis. mBio 7:e00166. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00166-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieslich K. 1985. Microbial side chain degradation of sterols. J Basic Microbiol 25:461–474. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620250713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarlera S, Denner EB. 2003. Sterolibacterium denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel cholesterol-oxidizing, denitrifying member of the beta-Proteobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 53:1085–1091. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warnke M, Jacoby C, Jung T, Agne M, Mergelsberg M, Starke R, Jehmlich N, von Bergen M, Richnow HH, Brüls T, Boll M. 2017. A patchwork pathway for oxygenase-independent degradation of side chain containing steroids. Environ Microbiol 19:4684–4699. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang FC, Chen YL, Tang SL, Yu CP, Wang PH, Ismail W, Wang CH, Ding JY, Yang CY, Yang CY, Chiang YR. 2016. Integrated multi-omics analyses reveal the biochemical mechanisms and phylogenetic relevance of anaerobic androgen biodegradation in the environment. ISME J 10:1967–1983. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiang YR, Ismail W, Müller M, Fuchs G. 2007. Initial steps in the anoxic metabolism of cholesterol by the denitrifying Sterolibacterium denitrificans. J Biol Chem 282:13240–13249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dermer J, Fuchs G. 2012. Molybdoenzyme that catalyzes the anaerobic hydroxylation of a tertiary carbon atom in the side chain of cholesterol. J Biol Chem 287:36905–36916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.407304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang PH, Lee TH, Ismail W, Tsai CY, Lin CW, Tsai YW, Chiang YR. 2013. An oxygenase-independent cholesterol catabolic pathway operates under oxic conditions. PLoS One 8:e66675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warnke M, Jung T, Jacoby C, Agne M, Feller FM, Philipp B, Seiche W, Breit B, Boll M. 2018. Functional characterization of three specific acyl-coenzyme A synthetases involved in anaerobic cholesterol degradation in Sterolibacterium denitrificans Chol1S. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02721-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02721-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang PH, Leu YL, Ismail W, Tang SL, Tsai CY, Chen HJ, Kao AT, Chiang YR. 2013. Anaerobic and aerobic cleavage of the steroid core ring structure by Steroidobacter denitrificans. J Lipid Res 54:1493–1504. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M034223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang PH, Yu CP, Lee TH, Lin CW, Ismail W, Wey SP, Kuo AT, Chiang YR. 2014. Anoxic androgen degradation by the denitrifying bacterium Sterolibacterium denitrificans via the 2,3-seco pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3442–3452. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03880-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowe AM, Casabon I, Brown KL, Liu J, Lian J, Rogalski JC, Hurst TE, Snieckus V, Foster LJ, Eltis LD. 2017. Catabolism of the last two steroid rings in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other bacteria. mBio 8:e00321-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00321-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kniemeyer O, Heider J. 2001. Ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, a novel hydrocarbon-oxidizing molybdenum/iron-sulfur/heme enzyme. J Biol Chem 276:21381–21386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson HA, Pelletier DA, Spormann AM. 2001. Isolation and characterization of anaerobic ethylbenzene dehydrogenase, a novel Mo-Fe-S enzyme. J Bacteriol 183:4536–4542. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.15.4536-4542.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strijkstra A, Trautwein K, Jarling R, Wöhlbrand L, Dörries M, Reinhardt R, Drozdowska M, Golding BT, Wilkes H, Rabus R. 2014. Anaerobic activation of p-cymene in denitrifying betaproteobacteria: methyl group hydroxylation versus addition to fumarate. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:7592–7603. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02385-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimaldi S, Schoepp-Cothenet B, Ceccaldi P, Guigliarelli B, Magalon A. 2013. The prokaryotic Mo/W-bisPGD enzymes family: a catalytic workhorse in bioenergetic. Biochim Biophys Acta 1827:1048–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rugor A, Wójcik-Augustyn A, Niedzialkowska E, Mordalski S, Staroń J, Bojarski A, Szaleniec M. 2017. Reaction mechanism of sterol hydroxylation by steroid C25 dehydrogenase—homology model, reactivity and isoenzymatic diversity. J Inorg Biochem 173:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2017.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warnke M, Jung T, Dermer J, Hipp K, Jehmlich N, von Bergen M, Ferlaino S, Fries A, Müller M, Boll M. 2016. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 synthesis by enzymatic steroid side-chain hydroxylation with water. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 55:1881–1884. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian XQ, Holick MF. 1995. Catalyzed thermal isomerization between previtamin D3 and vitamin D3 via beta-cyclodextrin complexation. J Biol Chem 270:8706–8711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rugor A, Tataruch M, Staroń J, Dudzik A, Niedzialkowska E, Nowak P, Hogendorf A, Michalik-Zym A, Napruszewska DB, Jarzębski A, Szymańska K, Białas W, Szaleniec M. 2017. Regioselective hydroxylation of cholecalciferol, cholesterol and other sterol derivatives by steroid C25 dehydrogenase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:1163–1174. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7880-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martín-Moldes Z, Zamarro MT, Del Cerro C, Valencia A, Gómez MJ, Arcas A, Udaondo Z, García JL, Nogales J, Carmona M, Díaz E. 2015. Whole-genome analysis of Azoarcus sp. strain CIB provides genetic insights to its different lifestyles and predicts novel metabolic features. Syst Appl Microbiol 38:462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anders HJ, Kaetzke A, Kampfer P, Ludwig W, Fuchs G. 1995. Taxonomic position of aromatic-degrading denitrifying pseudomonad strains K 172 and KB 740 and their description as new members of the genera Thauera, as Thauera aromatica sp. nov., and Azoarcus, as Azoarcus evansii sp. nov., respectively, members of the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 45:327–333. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-2-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu S, Zhang D, Wang D, Zhi Y, Zhou P. 2017. Heterologous expression and biochemical characterization of assimilatory nitrate and nitrite reductase reveals adaption and potential of Bacillus megaterium NCT-2 in secondary salinization soil. Int J Biol Macromol 101:1019–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann T, Leimkühler S. 2013. The oxygen-tolerant and NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase from Rhodobacter capsulatus is able to catalyze the reduction of CO2 to formate. FEBS J 280:6083–6096. doi: 10.1111/febs.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilton JC, Temple CA, Rajagopalan KV. 1999. Re-design of Rhodobacter sphaeroides dimethyl sulfoxide reductase. Enhancement of adenosine N1-oxide reductase activity. J Biol Chem 274:8428–8436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kappler U, McEwan AG. 2002. A system for the heterologous expression of complex redox proteins in Rhodobacter capsulatus: characterisation of recombinant sulphite:cytochrome c oxidoreductase from Starkeya novella. FEBS Lett 529:208–214. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malasarn D, Keeffe JR, Newman DK. 2008. Characterization of the arsenate respiratory reductase from Shewanella sp. strain ANA-3. J Bacteriol 190:135–142. doi: 10.1128/JB.01110-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollock VV, Conover RC, Johnson MK, Barber MJ. 2002. Bacterial expression of the molybdenum domain of assimilatory nitrate reductase: production of both the functional molybdenum-containing domain and the nonfunctional tungsten analog. Arch Biochem Biophys 403:237–248. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenbrink F, Schink B, Kroneck PM. 2011. Exploring the active site of the tungsten, iron-sulfur enzyme acetylene hydratase. J Bacteriol 193:1229–1236. doi: 10.1128/JB.01057-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu SY, Rothery RA, Weiner JH. 2015. Pyranopterin coordination controls molybdenum electrochemistry in Escherichia coli nitrate reductase. J Biol Chem 290:25164–25173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.665422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu GD, Okamura WH. 1995. Synthesis of vitamin D (calciferol). Chem Rev 95:1877–1952. doi: 10.1021/cr00038a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi K, Yasuda K, Sugimoto H, Ikushiro S, Kamakura M, Kittaka A, Horst RL, Chen TC, Ohta M, Shiro Y, Sakaki T. 2010. Three-step hydroxylation of vitamin D3 by a genetically engineered CYP105A1: enzymes and catalysis. FEBS J 277:3999–4009. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang DJ, Im JH, Kang JH, Kim KH. 2015. Bioconversion of vitamin D3 to calcifediol by using resting cells of Pseudonocardia sp. Biotechnol Lett 37:1895–1904. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-1862-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakaki T, Sugimoto H, Hayashi K, Yasuda K, Munetsuna E, Kamakura M, Ikushiro S, Shiro Y. 2011. Bioconversion of vitamin D to its active form by bacterial or mammalian cytochrome P450. Biochim Biophys Acta 1814:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yasuda K, Endo M, Ikushiro S, Kamakura M, Ohta M, Sakaki T. 2013. UV-dependent production of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 in the recombinant yeast cells expressing human CYP2R1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 434:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasutake Y, Nishioka T, Imoto N, Tamura T. 2013. A single mutation at the ferredoxin binding site of P450 Vdh enables efficient biocatalytic production of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. Chembiochem 14:2284–2291. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tschech A, Fuchs G. 1987. Anaerobic degradation of phenol by pure cultures of newly isolated denitrifying pseudomonads. Arch Microbiol 148:213–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00414814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinert T, Huwiler SG, Kung JW, Weidenweber S, Hellwig P, Stärk HJ, Biskup T, Weber S, Cotelesage JJ, George GN, Ermler U, Boll M. 2015. Structural basis of enzymatic benzene ring reduction. Nat Chem Biol 11:586–591. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mergelsberg M, Willistein M, Meyer H, Stärk HJ, Bechtel DF, Pierik AJ, Boll M. 2017. Phthaloyl-CoA decarboxylase from Thauera chlorobenzoica: the prenylated flavin, K+, and Fe2+-dependent key enzyme of anaerobic phthalate degradation. Environ Microbiol 19:3734–3744. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic tree of active site α-subunits from S25DH-like enzymes inside the DMSOR family of MoCo-containing enzymes. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.5 MB (558.2KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

UPLC chromatograms showing the conversion of various steroid substrates by different recombinant S25DHs from Sterolibacterium denitrificans heterologously produced in T. aromatica. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.2 MB (229.9KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

SDS-PAGE (12.5%) of the active fractions obtained during enrichment of S25DH1 (α1β3γ3-subunits) in Azoarcus sp. strain CIB. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 0.2 MB (181.7KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Mass spectrometric analysis of S25DH1 from S. denitrificans heterologously produced in T. aromatica K172. Download TABLE S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.7KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Growth of S. denitrificans in a 200-liter fermenter with 3 mM β-sitosterol under denitrifying conditions. Download FIG S4, PDF file, 0.2 MB (160.7KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Mass spectrometric analysis of enriched protein from wild-type S. denitrificans catalyzing β-sitost-4-en-3-one C-25 hydroxylation. Download TABLE S2, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.9KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Oligonucleotide primers used for heterologous production of steroid C-25 dehydrogenases. Download TABLE S3, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2018 Jacoby et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.