Abstract

The aim of this investigation was to examine a theoretically based mechanism by which men’s adherence to antifeminine norms is associated with their perpetration of sexual aggression toward intimate partners. Participants were 208 heterosexual men between the ages of 21–35 who had consumed alcohol in the past year. They were recruited from a large southeastern United States city. Participants completed self-report measures of hegemonic masculinity (i.e., antifemininity, sexual dominance), masculine gender role stress, and sexual aggression toward an intimate partner during the past 12 months. Results indicated that adherence to the antifemininity norm and the tendency to experience stress when in subordinate positions to women were indirectly related to sexual aggression perpetration via adherence to the sexual dominance norm. Thus, the men who adhere strongly to these particular hegemonic masculine norms may feel compelled to be sexually aggressive and/or coercive toward an intimate partner in order to maintain their need for dominance within their intimate relationship. Implications for future research and sexual aggression prevention programming are discussed.

Keywords: sexual aggression, hegemonic masculinity, masculine gender role stress, antifemininity, sexual dominance

Over the past 30 years, violence against women has become recognized as a serious public health issue across the globe. Sexual aggression occurs at alarming rates, and research conducted in the United States has shown that women are more likely to experience an attempted or completed rape than men (Black et al., 2011; Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987; Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). In addition, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS, Black et al., 2011) found that 1 in 5 women have experienced rape victimization in their lifetime, and 51% of female rape survivors reported victimization by a current or former intimate partner. Consistent with these data, research indicates that sexual aggression against women is primarily perpetrated by men (e.g., Black et al., 2011; Koss et al., 1987; Walters, Chen, & Breiding, 2013). Given these data, researchers have worked to understand the risk factors associated with men’s perpetration of sexual aggression. To this end, much research has demonstrated that men who endorse and internalize several aspects of hegemonic masculinity are at greater risk for perpetrating sexual aggression toward women (for reviews, see Murnen, Wright, & Kaluzny, 2002; Zurbriggen, 2010). Specifically, traditional masculine norms are thought to function in a way that promotes men’s dominance and women’s subordination. Thus, we theorized that a basic tactic for maintaining dominance over women is through sexual aggression; this is especially true in situations that threaten a man’s dominance.

This hypothesis attempts to transcend the basic assumption that endorsement of hegemonic norms invariably facilitates sexual aggression by examining how different norms function and interact with other risk factors that might elicit men’s need to maintain dominance over women. Indeed, a majority of men who endorse hegemonic masculine norms are not sexually aggressive. Thus, a potential benefit of this nuanced approach is to better understand the etiology of sexual aggression and, as a result, inform prevention and intervention efforts. Although research has examined numerous bivariate relationships among these variables, few studies (e.g., Malamuth, Linz, Heavey, Barnes, & Acker, 1995; Truman, Tokar, & Fischer, 1996) have tested this hypothesized theoretical mechanism through explanatory, multivariate models. Thus, the present study sought to examine mechanisms by which hegemonic masculinity is related to men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward their female intimate partners. Additionally, as will be reviewed below, studies indicate that adherence to some, but not all, gender role norms are risk factors for sexual aggression (Murnen et al., 2002; Sheffield, 1987). For example, many studies have supported the association between attitudes supporting men’s power and control in relationships, a dimension of hegemonic masculine gender roles, and perpetration of sexual aggression toward women (e.g., Anderson & Anderson, 2008; Eisler, Franchina, Moore, Honeycutt, & Rhatigan, 2000; Malamuth, Heavey, & Linz, 1996). Thus, the present study specifically aimed to deconstruct from where that desire originates and how it interacts with other factors to facilitate sexual aggression in the context of intimate partner relationships. Collectively, achieving these aims may contribute to our understanding of the mechanism by which hegemonic masculinity facilitates men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward women.

Hegemonic Masculinity

Hegemonic masculinity refers to the normative ideology that to be a man is to be dominant in society and that the subordination of women is required to maintain such power (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Mankowski & Maton, 2010). While there are individual differences in male gender role socialization, this specific masculinity works to position men in a space of power, thus, it is often the ideal form of masculinity that men are socialized to achieve (Beasley, 2008; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). To demonstrate hegemonic masculinity, men are expected to adhere to a strict set of prescribed masculine gender roles that work to promote male dominance through a subordination and overall distrust of femininity (Malamuth, Sockloskie, Koss, & Tanaka, 1991). Myriad norms of hegemonic masculinity have been advanced. For instance, men are encouraged to avoid displaying traits associated with femininity through restrictive emotionality, toughness, and aggressive behaviors (Murnen et al., 2002). Levant, Rankin, Williams, Hasan, and Smalley (2010) established seven dimensions of hegemonic male role norms: restrictive emotionality, self-reliance through mechanical skills, negativity toward sexual minorities, avoidance of femininity, importance of sex, toughness, and dominance. Other theorists have put forth similar conceptualizations of the prescribed norms related to hegemonic masculinity (e.g., Thompson & Pleck, 1986).

Masculine Gender Role Stress

Men who strictly adhere to hegemonic masculinity are more likely to experience stress in situations where masculinity is threatened (Eisler, Skidmore, & Ward, 1988; Malamuth et al., 1996). An individual’s appraisal of such situations as stressful and undesirable is defined as masculine gender role stress (Eisler et al., 1988). The gender-relevant situations that may elicit masculine gender role stress are multifold. One conceptualization of these was advanced by Eisler and colleagues’ (1988) development of the Masculine Gender Role Stress scale. This scale is comprised of five situations hypothesized to threaten hegemonic masculinity: physical inadequacy, emotional inexpressiveness, subordination to women, intellectual inferiority, and performance failure. Of relevance to the present study, situations that elicit stress due to subordination to women are those in which men are outperformed or made to feel vulnerable by a woman. This type of situation elicits anxiety for men who experience an inability to meet the standards prescribed by hegemonic male role norms (Eisler et al., 1988; Moore et al., 2008). These findings suggest that when men experience such stress from not living up to traditional masculine roles in these situations, they are likely to react in ways that reaffirm their masculinity.

Tactics for reaffirming masculinity have been shown to be maladaptive in nature with several negative consequences. For instance, masculine gender role stress has been linked to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, increased anger, and anxiety (Eisler et al., 2000; Moore & Stuart, 2004). However, while men can perform a multitude of actions to reaffirm their masculinity, aggression may be the most effective method because it is often viewed as the most evident symbol of manhood (Kimmel, 2000). Indeed, perpetrating aggression is oftentimes public, dangerous, and risky (e.g., Archer, 2004; Doyle, 1989; Vandello, Bosson, Cohen, Burnaford, & Weaver, 2008). Not surprisingly, research has demonstrated that masculine gender role stress is positively associated with men’s perpetration of violence against women (Eisler et al., 2000, 1988; Moore et al., 2008; Moore & Stuart, 2004). For instance, Moore and Stuart (2004) found that men who experience higher levels of masculine gender role stress were more likely to report higher levels of anger, negative attributions, and verbal aggression in response to situations in which a female threatened their masculinity. Collectively, these data suggest that men who maintain a strict adherence to masculine gender role norms react to gender-relevant stress through aggressive behavior. This is likely because men who experience such stress feel that they need to reassert their masculinity through behaviors that subordinate others (e.g., violence). One important example of this phenomenon is men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward women in order to establish dominance (Lonsway & Fitzgerald, 1994; Malamuth et al., 1996; Moore et al., 2008; Murnen et al., 2002). Other forms of aggressive behavior (e.g., physical, verbal) also function to establish dominance. However, the use of sexual aggression within intimate relationships is the ultimate demonstration of dominance and control and most closely embodies hegemonic masculinity. In contrast, the reviewed theory posits that men who do not experience high levels of gender-related stress likely do not feel the need to assert their dominance; thus, they would not perceive the need to portray a specific image of masculinity via the use of sexual aggression.

Deconstruction of Hegemonic Masculinity, Gender Role Stress, and Sexual Aggression

Despite the reviewed literature, there exist critical gaps in our understanding of the association between hegemonic masculinity and sexual aggression. For example, little research (e.g., Malamuth et al., 1995; Truman et al., 1996) has worked to deconstruct the various dimensions of hegemonic masculinity and masculine gender role stress in a way that allows for a more fine-grained analysis of the association between these constructs and their relation to sexual aggression perpetration. Masculinity and masculine gender role stress are inherently complex constructs. Thus, examination of the interrelationships between specific facets of these overarching constructs and men’s perpetration of sexual aggression is an important endeavor with both theoretical and applied value. For instance, this approach would advance theoretical work on the mechanisms that underlie sexual aggression, shed light on specific processes involved in men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward their intimate (and perhaps nonintimate) partners, and inform the development of potentially effective prevention programs (Malamuth et al., 1996; Moore et al., 2008).

Antifemininity

Antifemininity, or men’s avoidance of femininity, refers to men’s internalized desire to avoid being perceived as feminine by abstaining from actions, thoughts, and feelings that are commonly associated with femininity (Zurbriggen, 2010). Antifemininity also involves a fear of traditional feminine values and behaviors (e.g., appearing weak or docile), and therefore encourages restricting one’s emotions and portraying a façade of toughness (O’Neil, 1981). Indeed, boys are often socialized to replace feminine emotions and develop a macho personality through antifemininity (McCreary, 1994; Murnen et al., 2002; O’Neil, 2008). Internalization of antifeminine norms and attitudes serves as a necessary component of the socialization of males in order to achieve perceived masculine dominance in society (O’Neil, 2008). Antifemininity is therefore internalized as the basis for achieving dominance in interpersonal interactions (O’Neil, 2008; Truman et al., 1996). As a result, adhering to the antifemininity norm is also associated with the devaluation of women because femininity as a whole is seen as inferior and less desirable than masculinity (Murnen et al., 2002; O’Neil, 1981; Zurbriggen, 2010). The internalization of antifemininity has been associated with rape supportive attitudes and men’s perpetration of sexual aggression against women (Luddy & Thompson, 1997; Thompson & Cracco, 2008; Truman et al., 1996).

Masculine Gender Role Stress

Moore et al. (2008) examined the extent to which the five dimensions of masculine gender role stress independently and collectively predicted different forms of aggression toward intimate partners. Interestingly, each dimension of masculine gender role stress was found to correlate with a different form of intimate partner aggression. Pertinently, men’s tendency to experience stress when in subordinate positions to women was found to be significantly associated with sexual coercion. In a similar deconstruction of six dimensions of male role norms (i.e., feminine avoidance, status and achievement, toughness and aggression, restricted emotionality, nonrelational sexuality, and dominance), Zurbriggen (2010) found each of these six dimensions to be independently, as well as collectively, correlated with sexual aggression perpetration. Given this research, it is clear that the relationship between male role norm adherence, masculine gender role stress, and sexual aggression perpetration is highly complex and encompasses several different possible paths. However, no study to date has examined specifically how distinct masculine norms directly, or indirectly, relate to sexual aggression as a function of distinct dimensions of masculine gender role stress. The current study aimed to address this gap in the literature.

Dominance

The desire for dominance and power is central to hegemonic masculinity and refers to men’s need to control others in order to achieve status according to oneself, as well as in society as a whole (Levant et al., 2010). Obtaining and maintaining status and power in society and in interpersonal interactions involves the objectification or dehumanization of others, particularly women, and a need to control others and hold power. This involves a distrust of others and a willingness to manipulate them (Levant et al., 2010; Malamuth et al., 1995; Zurbriggen, 2010). Further, men who have internalized and adhere to this particular masculine norm are more likely to take extreme measures (e.g., violence and aggression) in order to maintain their dominance in society. Consistent with this theory, adherence to the dominance norm has been positively associated with rape-supportive beliefs and men’s perpetration of sexual aggression both directly and indirectly in combination with other risk factors, such as acceptance of interpersonal violence against women and adversarial sex beliefs (e.g., Abbey, Jacques-Tiura, & LeBreton, 2011; Anderson & Anderson, 2008; Malamuth et al., 1995; Rudman & Mescher, 2012).

Theoretical Integration

There exist numerous theoretical explanations for men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward female intimates (e.g., Malamuth et al., 1991). One line of research has demonstrated that the avoidance of femininity may be achieved via dominance over others, particularly women, within interpersonal interactions (Malamuth et al., 1991; Mosher & Sirkin, 1984; Murnen et al., 2002; Zurbriggen, 2010). As a social construct, the avoidance of femininity is argued to be the basis of hegemonic masculinity ideology because it encourages the maintenance of male dominance in society by placing the feminine role as subordinate and as something to be avoided (O’Neil, 2008). Thus, the established relationship between antifemininity and sexual aggression is hypothesized to be mediated by men’s desire for dominance (e.g., Malamuth et al., 1995; Truman et al., 1996).

Further, this relationship may be particularly strong among men who experience gender role stress in situations where they are in a subordinate role to women. Thus, when a high gender role stress man experiences a challenge to his achieved antifeminine and dominant status by a female (e.g., the experience of sexual rejection by a female), he should experience gender role stress for failing to adhere to the prescribed norms associated with achieving hegemonic masculinity (Moore et al., 2008). The most likely and immediate reaction is to regain that power by reaffirming his identity as a dominant male. In sexual situations, especially in the context of intimate partner relationships, the reaffirmation of hegemonic masculinity can be clearly achieved through the use of sexual aggression. Thus, the indirect effect of antifemininity on sexual aggression via dominance should be particularly strong among men prone to feel gender-relevant stress from being subordinated by a female intimate partner (Moore & Stuart, 2004, 2005). In contrast, this indirect effect should be weaker, or not at all significant, among men who are not prone to experience such stress. Indeed, these men would presumably experience less gender-relevant stress “in the moment” and consequently be less motivated to assert male dominance to alleviate that stress.

The Present Study

Given this theoretical background and analysis, we sought to examine the following research questions: (1) Does dominance mediate the relation between antifemininity and the perpetration of sexual aggression?, and (2) What (if any) is the role of men’s experience of stress related to subordination to women in this relationship? We advanced an overarching hypothesis of moderated mediation, which posited that the effect of antifemininity on sexual aggression would be mediated by sexual dominance, and this indirect effect would be significantly more positive among men high, relative to low, in masculine gender role stress related to subordination to women.

Method

This study utilized archival data drawn from the first phase of a larger two phase investigation on the effects of alcohol on men’s sexual aggression toward women (Parrott et al., 2012). This first phase involved the completion of a questionnaire battery, whereas the second phase involved an alcohol administration laboratory protocol. Thus, although the focus of the present study did not examine alcohol-related effects, all participants who presented to the laboratory had reported via telephone screening interview that they consumed, on average, three or more alcoholic drinks per drinking day during the past year as well as nonproblematic drinking patterns. The present hypotheses are novel, and the analytic plan was developed specifically to address these aims.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were male social drinkers between the ages of 21 and 35 recruited from the metro-Atlanta community through Internet advertisements and local newspapers. Respondents were initially screened by telephone to confirm self-reported alcohol consumption during the past year. In order to ensure that respondents could tolerate the alcohol administered in the laboratory during the second phase of the study (data not reported here), respondents were deemed eligible if they reported consumption of, on average, three or more drinks per occasion at an average rate of at least 3 days per week over the past year; nondrinkers were excluded. In addition, respondents were screened for psychopathological diagnoses, medical conditions, and head injuries that might conflict with alcohol consumption. Those respondents who affirmed any of the aforementioned criteria were deemed ineligible. In addition, the Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Pokorny, Miller, & Kaplan, 1972) was administered during the telephone interview in order to ensure that only individuals who denied significant alcohol-related problems were recruited. Of the respondents, 261 eligible men were scheduled for an appointment to participate.

Because the current study sought to examine a mechanism for heterosexual men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward female intimate partners, only men who self-identified as heterosexual and who had been in an intimate relationship in the past year were examined. Of the original sample, nine did not self-identify as heterosexual and 44 reported that they had not been in an intimate relationship during the past year. Thus, the final usable sample consisted of 208 men aged 21–35 (M = 25.07, SD = 3.35) who had been in a heterosexual intimate relationship during the past year, and consisted of 63% African Americans, 27% Caucasians, 9% who identified as more than one race, and 1% who identified with another racial group or did not indicate their racial identity. The sample reported an average of 14.1 year of education (SD = 2.37), earned $21,854 per year (SD = $16,924), and 82% had never been married. Men reported consuming an average of 4.50 (SD = 2.5) alcoholic drinks per drinking day approximately 2.30 (SD = 1.39) days per week. All participants received $10 per hour for their participation. This study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Materials

Demographic form

This form assessed participants’ age, ethnic background, race, highest level of education, self-identified sexual orientation, and income level.

Antifemininity

The Revised Male Role Norms Inventory–Revised (MRNI-R; Levant et al., 2010) was used to measure men’s adherence to the antifemininity norm. The MRNI-R is a 53-item measure that is scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of endorsement of traditional masculinity ideology. Seven subscales assess individuals’ endorsement of different dimensions of traditional masculinity ideology, including: Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities, Self-reliance, Aggression, Dominance, Nonrelational Sexuality, Restrictive Emotionality, and Avoidance of Femininity. Of these subscales, the current study only examined the Avoidance of Femininity subscale. This scale consists of eight items with questions reflecting an adherence to the male role norm that assumes that men should not endorse or exhibit beliefs or behaviors that are traditionally viewed as being feminine (e.g., “A man should prefer watching action movies to reading romantic novels”). The internal consistency coefficient for this subscale is .89 in a standardized sample (Levant et al., 2010). An alpha reliability of .81 was obtained in the present sample.

Masculine gender role stress

The Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale (MGRSS, Eisler & Skidmore, 1987) was administered to assess men’s tendency to experience masculine gender role stress. This scale is a widely used and well-validated self-report measure of the extent to which gender relevant situations (e.g., “Being outperformed at work by a woman”) are cognitively appraised as stressful or threatening. It consists of 40 items and responses may range from 0 (not at all stressful) to 5 (extremely stressful). Higher scores reflect more dispositional gender role stress. This scale has been shown to identify situations that are cognitively more stressful for men than women. Although masculine gender role stress is related to masculine ideology (McCreary, Newcomb, & Sadava, 1998; Walker, Tokar, & Fischer, 2000), this construct is a “unique and cohesive construct that can be measured globally” (Walker et al., 2000, p. 105). Research indicates that it exhibits good psychometric properties (Eisler et al., 1988; Thompson, Pleck, & Ferrera, 1992). Prior research conducted with the proposed target population has found masculine gender role stress scores to be well distributed (i.e., unimodal, not skewed) with good alphas. Of its five subscales, the current study only examined the Subordination to Women subscale. This subscale consists of nine items that assess the degree to which respondents experience stress in situations in which they would be subordinate to women (e.g., “Being outperformed by a woman at work”). Research has demonstrated this subscale to have high internal reliability with a sample of college males (α = .80) (van Well, Kolk, & Arrindell, 2005), which was consistent with the present sample (α = .83).

Sexual dominance

The Sexual Dominance Scale (Nelson, 1979) was used to assess participants’ level of sexual dominance. This 8-item subscale is part of the more general Sexual Functions Inventory (Nelson, 1979) that assesses the degree to which various feelings and sensations are important to respondents as motives for sexual behavior. The dominance subscale assesses the degree by which feelings of control over one’s partner motivate sexuality (e.g., “I enjoy the feeling of having someone in my grasp,” “I enjoy the conquest”). Responses are given on a 7-point scale. Research indicates good psychometric properties for this subscale, with an internal consistency coefficient of .77 (Malamuth et al., 1995). An alpha reliability of .80 was obtained in the present sample.

Sexual aggression

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Bony-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was used to measure sexual aggression within intimate relationships. The CTS-2 is a widely used and well-validated self-report instrument that measures the frequency of aggression as well as positive interpersonal behaviors within intimate relationships (Vega & O’Leary, 2007). Its 78 items are coupled to assess both perpetration of and victimization from different forms of aggression within intimate relationships. In the current study, sexual aggression during the past year was assessed with the 7-item sexual coercion subscale, which assesses both minor (e.g., “Have you insisted on sex when your partner did not want to [but did not use physical force]?”), and severe sexual coercion (e.g., “Have you used force [like hitting, holding down, or using a weapon] to make your partner have sex?”). Participants are instructed to indicate on a 7-point scale how many times they perpetrated sexual aggression toward their intimate partner during the past year. Responses range from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). In the present sample, an alpha reliability of .70 was obtained for this 7-item subscale. Following Straus and colleagues (1996), a chronicity variable for sexual coercion was computed by adding the midpoints of the score range for each item to form a total score. For example, if a participant indicated a response of 3–5 times in the past year, his score would be a 4. This method of scoring the CTS-2 permits examination of the frequency of sexually aggressive acts perpetrated against intimate partners.

Procedure

Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants were greeted and led to a private experimental room. After providing informed consent, participants completed a questionnaire battery on a computer using MediaLab 2006 software (Jarvis, 2006). Additional questionnaires were also completed but are unrelated to the proposed study and are thus not reported here. The experimenter provided instructions on how to operate the computer program that administered the questionnaire battery and was available to answer any questions during the session. After completing the questionnaire battery, participants were informed of their eligibility to participate in the laboratory phase of the project. All participants were debriefed by trained project assistants or doctoral students in clinical psychology.

Results

Analytic Strategy

Because antifemininity, subordination toward women and sexual dominance were continuous variables, they were z-transformed to enhance interpretability; preliminary descriptive analyses revealed that sexual aggression was positively skewed to an extent that it could not be considered normally distributed; therefore, a square root transformation was performed on this variable prior to analysis, which resulted in an approximately normal distribution. Little’s MCAR test of both item (χ2 = 637.96, p = .242) and scale-level (χ2 = 2.87, p = .41) scores supported the assumption that there was not a pattern of missing data in this sample. The hypothesized model was fit to data within a path analytic framework using Mplus v. 6.1 (Muthén, & Asparouhov, 2002). All models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation. Indirect effects, corresponding standard errors, and confidence intervals were computed using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 draws (Bollen & Stine, 1990; Preacher & Hayes, 2008a). The moderated mediation model estimated was structurally consistent with Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes’ (2007) Model 2. Parameters used to evaluate the model’s fit to the data included a nonsignificant chi-square (p > .05), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below .05, comparative fit index (CFI) above .95, and a standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) of below .06 (Kline, 2010).

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations, ranges, and correlation coefficients for pertinent study variables are presented in Table 1. Significant positive correlations were detected among antifemininity, dominance, subordination to women, and perpetration of sexual aggression toward intimate partners.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations Among Path Model Variables

| Descriptives | Correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Variable | # items | scale | α | M | SD | range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. Antifemininity | 8 | 1–7 | .81 | 4.67 | 1.20 | 1–7 | — | .41*** | .30*** | .15* |

| 2. STW | 9 | 0–5 | .83 | 1.07 | 0.90 | 0–4.11 | — | .32*** | .18** | |

| 3. Sexual dominance | 8 | 1–7 | .80 | 1.55 | 0.62 | 0–3 | — | .33*** | ||

| 4. Sexual aggressiont | 7 | 0–25 | .70 | 1.52 | 2.10 | 0–9.86 | — | |||

Note. N = 208. Antifemininity = Male Role Norms Inventory–Avoidance of Femininity Subscale; STW = Masculine Gender Role Stress–Subordination to Women Subscale; Sexual Dominance = Nelson Sexual Dominance Scale; Sexual Aggression = Conflict Tactics Scale–Sexual Coercion Subscale.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Per item scale means, standard deviations, and ranges before square root transformation.

Hypothesized Moderated Mediational Model

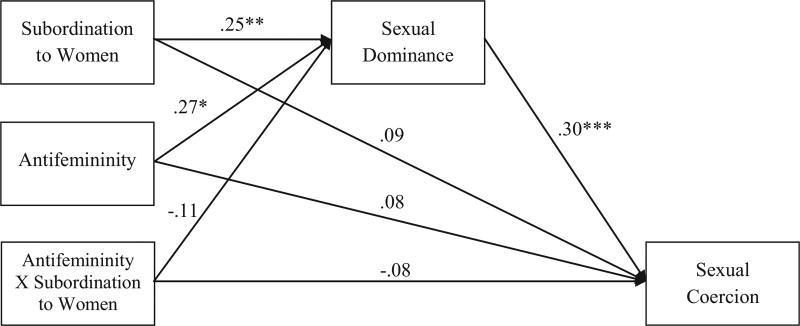

Standardized coefficients associated with the hypothesized model are presented in Figure 1. Although the main effects of antifemininity and subordination to women on sexual dominance were significant and in hypothesized directions, their interactive effect on sexual dominance did not reach significance. Sexual dominance was a positive and significant predictor of sexual aggression. Neither antifemininity nor subordination to women nor their interaction directly influenced sexual aggression; however, antifemininity and subordination to women indirectly influenced sexual aggression via sexual dominance (see Table 2). Taken together, the moderation portion of the model was not supported, although the prospect of sexual dominance significantly mediating paths from both antifemininity and subordination to women to sexual aggression remained promising. We therefore removed the interaction term to specifically test these mediational pathways.

Figure 1.

The hypothesized moderated mediation model of antifemininity, sexual dominance, and stress associated with subordination to women on sexual aggression. Note: All estimates standardized with regard to both X and Y. *p < .01. **p < .001.

Table 2.

Estimates of Indirect Effects of Antifemininity and Subordination to Women on Sexual Aggression Via Sexual Dominance

| Estimate | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderated mediation model | |||

| Antifemininity | .08 | .04 | .002, .16 |

| Subordination to women | .08 | .03 | .02, .13 |

| Full mediation model | |||

| Antifemininity | .06 | .03 | .01, .11 |

| Subordination to women | .07 | .03 | .02, .12 |

| Final mediation model | |||

| Antifemininity | .06 | .03 | .01, .12 |

| Subordination to women | .08 | .03 | .03, .13 |

Note. Estimates are standardized effects with regard to both X and Y, also known as indices of mediation (Preacher & Hayes, 2008b).

Double Mediation Model

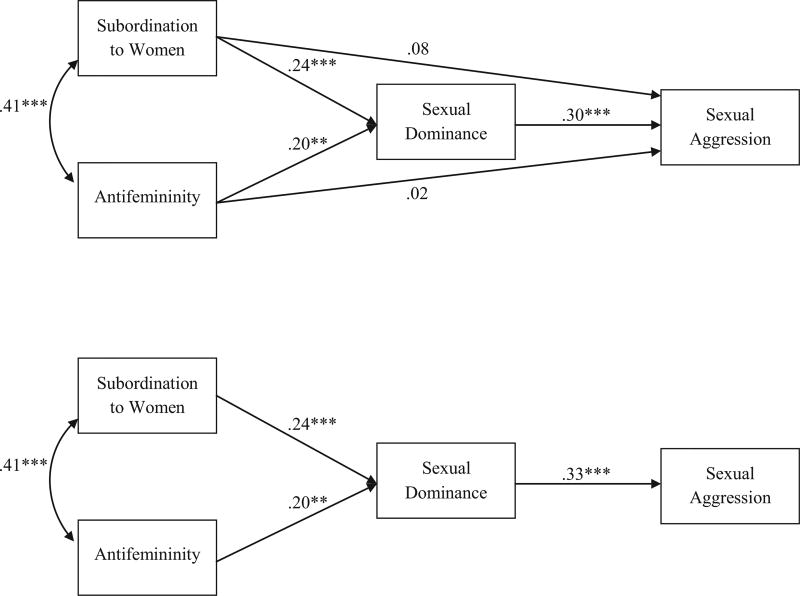

The revised model was constructed to test the effects of antifemininity and subordination to women on sexual aggression both mediated by sexual dominance. As detailed in Figure 2 (top), both antifemininity and subordination to women were positively and significantly associated with sexual dominance; in turn, sexual dominance was significantly and positively associated with sexual aggression. Although antifemininity and subordination to women did not directly affect sexual aggression, these variables affected sexual aggression indirectly via sexual dominance (see Table 2). This pattern of effects within the full model suggests sexual dominance mediates the effects of both antifemininity and subordination to women on sexual aggression.

Figure 2.

Mediation models of antifemininity, sexual dominance, and stress associated with subordination to women on sexual aggression. Top panel: Full mediation model. Bottom panel: Final mediation model after trimming nonsignificant paths. Note: All estimates standardized with regard to both X and Y. ** p < .01. ***p < .001.

Assessing the overall fit of the full model is difficult, however, because this model is saturated, leaving it to almost necessarily fit the data perfectly. We therefore decided to trim nonsignificant paths, one at a time, in order to adequately assess model fit and present a more parsimonious model. The smallest nonsignificant standardized coefficient, which reflected the effect of antifemininity on sexual aggression, was fixed to zero. Eliminating this path did not significantly affect model fit (χ2 difference = .12, df = 1, p > .05). The effect of subordination to women on sexual aggression remained nonsignificant after trimming the antifemininity effect and was therefore also fixed to zero, which did not significantly affect model fit (χ2 difference = 1.78, df = 1, p > .05). The resulting final model, presented in Figure 2 (bottom), fit the data well (χ2 = 1.90, df = 2, p = .39; RMSEA < .01, 90% CI = < .01, .12, probability RMSEA < = .05 = .59; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = .025). All significant effects from the full model remained including the indirect effects of antifemininity and subordination to women on sexual aggression via sexual dominance (see Table 2). This final model explained 13.5% of the variance in sexual dominance and 11% of the variance in sexual aggression.

Discussion

Past research has established that adherence to traditional male role norms and the experience of masculine gender role stress are related to men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward women (e.g., Hamburger, Hogben, McGowan, & Dawson, 1996; Malamuth et al., 1996). However, little research has examined the specific mechanisms by which these constructs facilitate sexual aggression (Malamuth et al., 1991; Moore et al., 2008; Zurbriggen, 2010). The present study sought to address this gap in the literature, particularly in the context of intimate relationships. A deconstructive model was initially developed that (1) specified a mediational path linking individual hegemonic masculine gender norms (i.e., adherence to the antifemininity and dominance norms) and sexual aggression, and (2) considered how this proposed path may vary as a function of individual differences in men’s experience of stress in gender relevant situations where they are subordinate to women. Specifically, we hypothesized that adherence to the antifemininity norm would indirectly predict men’s sexual aggression toward women via adherence to the dominance norm. We hypothesized further that this relation would be stronger among men who experienced higher levels of stress related to subordination to women.

Results did not fully support the hypothesized moderated mediation model. Bivariate associations evidenced a significant and positive association between antifemininity and sexual aggression, although this direct effect was not significant in the context of the moderated mediation model. Also, results detected a significant indirect effect of antifemininity on sexual aggression via sexual dominance. However, contrary to expectations, this indirect effect was not moderated by subordination to women. Although the moderation portion of the hypothesized model was not supported, the observed pattern of results indicated potential for sexual dominance to mediate paths from both antifemininity and subordination to women to sexual aggression. Indeed, subsequent revision of the hypothesized model indicated that antifemininity and subordination to women exert positive and significant indirect effects on sexual aggression via sexual dominance. In other words, men who report high levels of antifemininity and stress related to subordination to women are more likely to report sexual dominance, which then led to an increased frequency of sexual aggression.

These findings are consistent with previous research that has linked masculine role norms and masculine gender role stress to sexual aggression (e.g., Malamuth et al., 1996; Moore et al., 2008; Truman et al., 1996). Of particular import, these findings add to current literature by offering a theoretically based, but to date untested, mechanism by which traditional hegemonic masculine norms and masculine gender role stress facilitate sexual aggression. Specifically, the present data suggest that men who define their masculinity by avoiding femininity and/or feel threatened in situations where they are subordinate to a female intimate partner feel compelled to maintain dominance over women, and sexual aggression is one behavioral manifestation of this need to dominate. These findings expand on current literature by introducing both the antifemininity norm as well as the experience of stress related to subordination to women as important components of the relationship between men’s desire for dominance and sexual aggression perpetration (Anderson & Anderson, 2008; Malamuth et al., 1996; O’Neil, 2008). Clearly, additional variables are important to the prediction of sexual aggression and have been investigated in the context of more comprehensive models that account for more variance in men’s sexual aggression perpetration (e.g., Knight & Sims-Knight, 2005; Malamuth et al., 1996). Nevertheless, the present study provides a better understanding of the nuance in which gender-based cognitive factors are associated with sexual aggression.

The majority of studies on male sexual aggression are based upon samples from the United States. However, there is a developing literature from some European and Latin American countries that is beginning to demonstrate notable correspondence to the larger literature from U.S. samples (e.g., D’Abreu & Krahé, 2013; Krahé & Tomaszewska-Jedrysiak, 2011). There is also some research that compares individualistic and collectivist cultures. For example, Hall, Teten, DeGarmo, Sue, and Stephens (2005) compared mainland Asian American, Hawaiian Asian American, and European American subsamples and found cross-cultural support for the confluence model; however, some culture-specific moderators were identified. Nevertheless, due to the relatively limited international data in this area, it seems premature to draw firm conclusions regarding the cross-cultural generalizability of the presenting findings. At best, existing data suggest that if the present findings were to show cross-cultural generalizability, culture-specific factors would likely moderate the effects.

Implications

One theory of men’s sexual aggression toward women suggests that a desire for dominance and power over women is a salient factor that puts some men at risk for perpetration (Zurbriggen, 2010). The present findings are consistent with this view; however, results also indicate that the mechanisms that underline men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward intimate partners, and perhaps women generally, are more complex. For instance, it is important to pose the question of why some at-risk men seek dominance and power within heterosexual relationships. These results suggest that the desire to maintain an antifeminine status, as well as a dominant position that is specifically related to women’s subordination, are relevant factors in some at-risk men’s motivation for dominance. However, given that multiple “masculinities” and dimensions of those masculinities exist and are differentially linked to violence (for reviews, see Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Moore & Stuart, 2005), analysis of different gender norms should clarify further this complex relation. Thus, future research is needed that examines how some at-risk men’s adherence to distinct norms within traditional masculinity ideology and sensitivity to different gender-relevant threats independently and interactively influence men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward women (Moore et al., 2008).

As masculinity and gender-based attitudes are common risk factors targeted in sexual violence prevention programs (e.g., Men Can Stop Rape, Coaching Boys Into Men), such research will inform prevention practices related to sexual aggression perpetration. However, a conundrum exists in applying this research to prevention programs, such that in some effective programs changes in gender stereotypes accompany the decrease in sexual violence (e.g., Foshee et al., 1998) and in some programs violence against women decreases but gender-equitable attitudes do not (e.g., Miller et al., 2013). The present findings suggest the possibility that the overarching constructs of gender-socialization and masculinity are multidimensional and sufficiently complex; thus, their effects vary based on which aspects of the construct are targeted and a finer-grained understanding of gender-based attitudes is required to most effectively inform intervention programming.

Limitations

There are a few important limitations to the present study. First, because we used data that were collected for a different purpose, the sample is not representative of men in the community and is likely more at-risk. For example, the mean income level of our participants was relatively low. Thus, the economic stressors that were likely present for most men in the present sample should be considered when attempting to generalize these findings to national samples of young adult men. In addition, all men in the present sample reported average consumption of three or more alcoholic drinks per drinking day during the past year as well as nonproblematic drinking patterns. Thus, generalization of the present findings to nondrinking men, or men who exhibit alcohol-related problems (e.g., an alcohol use disorder), should be done with caution. That stated, nearly 50% of young adult men report typical consumption of three or more drinks per drinking day and consumption of five drinks or more drinks on a single occasion at least once in the past year (Chen, Dufour, & Yi, 2004). Our sample’s average consumption of 4.5 drinks per drinking day seems generally consistent with these data; thus, the generalizability of the present findings to other men nationally does not appear to be adversely impacted by the drinking eligibility criteria.

Second, because the current study used a cross-sectional design, we cannot confirm the temporal causality of the relationships tested. Future research is needed that examines attitudinal, motivational, and situational precursors to sexual aggression. For example, there exist several well-validated laboratory-based behavioral analogues that assess sexual aggression (e.g., Hall & Hirschman, 1994) and its precursors (e.g., Bernat, Stolp, Calhoun, & Adams, 1997). These paradigms could be modified to include a gender-relevant threat that places male participants in a subordinate position to a female. This modification would allow researchers to better examine the temporal relationships between the tested variables. Third, the measures of masculine gender role stress and sexual aggression prevented us from examining the specific situational context in which sexual aggression perpetration occurred. For instance, it remains unclear how many acts of sexual aggression were perpetrated in response to a gender-relevant threat to men’s dominance. Future research would benefit from utilizing instruments that better examine the situational contexts around sexual aggression perpetration (Walby & Myhill, 2001). For instance, the Statistics Canada survey measured women’s experiences of sexual aggression using items similar to those in the Conflict Tactics Scale, with additional items that better assessed the situational contexts around women’s experiences of sexual aggression by male intimate partners (Johnson & Sacco, 1995). A modified version of this scale that assesses the perpetrator’s experiences would provide a more ecological assessment of men’s perpetration of sexual aggression toward women. Finally, we measured men’s self-reported acts of sexual aggression toward intimate partners. Such questions are considered “sensitive” to the respondents, thus they are more likely to produce high nonresponse rates or larger measurement error (Catania, Gibson, Chitwood, & Coates, 1990). One way to address this limitation, as well as the previously discussed limitations, is to conduct in-person interviews. Such methods allow the researcher to develop a rapport with participants, which may make respondents more comfortable with answering sensitive questions (Walby & Myhill, 2001; Wells & Graham, 2003).

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the present study addresses crucial gaps in the research related to men’s perpetration of sexual aggression against women. The deconstruction of the overarching constructs of hegemonic masculinity and masculine gender role stress allow for a closer approximation of the distinct situational and motivational factors that influence sexual aggression perpetration. Of course, the present findings are but a first step in this process. Given the findings and theoretical premise of this study, future research and prevention strategies could benefit greatly through the use of programs and perspectives that work to further examine how men’s adherence to traditional male role norms and experiences of gender role stress uniquely relate to different forms of intimate partner violence.

Acknowledgments

This article is based in part on a Georgia State University Honors College undergraduate thesis conducted by Rachel M. Smith under the direction of Dominic J. Parrott. This research was supported by a joint grant by the Centers for Disease Control and Georgia State University. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We are grateful to Sarah Cook for her helpful comments.

Contributor Information

Rachel M. Smith, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia

Dominic J. Parrott, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia

Kevin M. Swartout, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia

Andra Teten Tharp, Division of Violence Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- Abbey A, Jacques-Tiura AJ, LeBreton JM. Risk factors for sexual aggression in young men: An expansion of the confluence model. Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37:450–464. doi: 10.1002/ab.20399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Anderson KB. Men who target women: Specificity of target, generality of aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:605–622. doi: 10.1002/ab.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology. 2004;8:291–322. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley C. Rethinking hegemonic masculinity in a globalizing world. Men and Masculinities. 2008;11:86–103. doi: 10.1177/1097184X08315102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat JA, Stolp S, Calhoun KS, Adams HE. Construct validity and test-retest reliability of a date rape decision-latency measure. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1997;19:315–330. doi: 10.1007/BF02229024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Stine R. Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociological Methodology. 1990;20:115–140. doi: 10.2307/271084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Gibson DR, Chitwood DD, Coates TK. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: Influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:339–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi H-Y. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: Results from the 2001–2002 NESARC survey. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society. 2005;19:829–859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Abreu L, Krahé B. Predicting sexual aggression in male college students in Brazil. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0032789. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JA. The male experience. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Franchina JJ, Moore TM, Honeycutt HG, Rhatigan DL. Masculine gender role stress and intimate abuse: Effects of gender relevance of conflict situations on men’s attributions and affective responses. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2000;1:30–36. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.1.1.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR. Masculine gender role stress: Scale development and component factors in the appraisal of stressful situations. Behavior Modification. 1987;11:123–136. doi: 10.1177/01454455870112001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR, Ward CH. Masculine gender-role stress: Predictor of anger, anxiety, and health-risk behaviors. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:133–141. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Arriaga XB, Helms RW, Koch GG, Linder GF. An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence prevention program. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:45–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Hirschman R. The relationship between men’s sexual aggression inside and outside the laboratory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:375–380. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Teten AL, DeGarmo DS, Sue S, Stephens KA. Ethnicity, culture, and sexual aggression: Risk and protective factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:830–840. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger ME, Hogben M, McGowan S, Dawson LJ. Assessing hypergender ideologies: Development and initial validation of a gender-neutral measure of adherence to extreme gender-role beliefs. Journal of Research in Personality. 1996;30:157–178. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.1996.0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis BG. MediaLab (Version 2006.1.41) [Software] New York, NY: Empirisoft Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson H, Sacco VF. Researching violence against women: Statistics Canada’s national survey. Canadian Journal of Criminology. 1995;37:281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel MS. The gendered society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Knight RA, Sims-Knight JE. Testing an etiological model for male juvenile sexual offending against females. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2005;13:33–55. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahé B, Tomaszewska-Jedrysiak P. Sexual scripts and the acceptance of sexual aggression in Polish adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2011;8:697–712. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2011.611034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Rankin TJ, Williams CM, Hasan NT, Smalley KB. Evaluation of the factor structure and construct validity of scores on the Male Role Norms Inventory-Revised (MRNI-R) Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2010;11:25–37. doi: 10.1037/a0017637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Rape myths. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1994;18:133–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00448.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luddy JG, Thompson EH. Masculinities and violence: A father-son comparison of gender traditionality and perceptions of heterosexual rape. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:462–477. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.4.462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Heavey CL, Linz D. The confluence model of sexual aggression: Combining hostile masculinity and impersonal sex. Sex Offender Treatment. 1996;23:13–37. doi: 10.1300/J076v23n03_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Linz D, Heavey CL, Barnes G, Acker M. Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict men’s conflict with women: A 10-year follow-up study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:353–369. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Sockloskie RJ, Koss MP, Tanaka JS. Characteristics of aggressors against women: Testing a model using a national sample of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:670–681. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankowski ES, Maton KI. A community psychology of men and masculinity: Historical and conceptual review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9288-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR. The male-role and avoiding femininity. Sex Roles. 1994;31:517–531. doi: 10.1007/BF01544277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Newcomb MD, Sadava SW. Dimensions of the male gender role: A confirmatory factor analysis in men and women. Sex Roles. 1998;39:81–95. doi: 10.1023/A:1018829800295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Tancredi DJ, McCauley HL, Decker MR, Virata MCD, Anderson HA, Silverman JG. One-year follow-up of a coach-delivered dating violence prevention program: A cluster randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart G. Effects of masculine gender role stress on men’s cognitive, affective, physiological, and aggressive responses to intimate conflict situations. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2004;5:132–142. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.5.2.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart G. A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005;6:46–61. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.6.1.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart GL, McNulty JK, Addis ME, Cordova JV, Temple JR. Domains of masculine gender role stress and intimate partner violence in a clinical sample of violent men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2008;9:82–89. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.9.2.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DL, Sirkin M. Measuring a macho personality constellation. Journal of Research in Personality. 1984;18:150–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(84)90026-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Wright C, Kaluzny G. If “boys will be boys,” then girls will be victims? A meta-analytic review of the research that relates masculine ideology to sexual aggression. Sex Roles. 2002;46:359–375. doi: 10.1023/A:1020488928736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Asparouhov T. Latent variable analysis with categorical outcomes: Multiple-group and growth modeling in Mplus. 2002 (Mplus Web Notes: No. 4). Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/webnotes/CatMGLong.pdf.

- Nelson PA. Personality, sexual functions, and sexual behavior: An experiment in methodology (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) University of Florida; Gainesville, FL: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM. Patterns of gender role conflict and strain: Sexism and fear of femininity in men’s lives. The Personnel and Guidance Journal. 1981;60:203–210. doi: 10.1002/j.2164-4918.1981.tb00282.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM. Summarizing 25 years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale: New research paradigms and clinical implications. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:358–445. doi: 10.1177/0011000008317057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Tharp AT, Swartout KM, Miller CA, Hall GCN, George WH. Validity for an integrated laboratory analogue of sexual aggression and bystander intervention. Aggressive Behavior. 2012;38:309–321. doi: 10.1002/ab.21429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny AD, Miller BA, Kaplan HB. The brief MAST: A shortened version of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1972;129:342–345. doi: 10.1176/ajp.129.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008a;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In: Hayes AF, Slater MD, Snyder LB, editors. The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008b. pp. 13–54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman LA, Mescher K. Of animals and objects: Men’s implicit dehumanization of women and likelihood of sexual aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012;38:734–746. doi: 10.1177/0146167212436401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield CJ. Sexual terrorism: The social control of women. In: Hess BB, Ferree MM, editors. Analyzing gender: A handbook of social science research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Bony-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, Cracco EJ. Sexual aggression in bars: What college men can normalize. The Journal of Men’s Studies. 2008;16:82–96. doi: 10.3149/jms.1601.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, Pleck JH. The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Sciences. 1986;29:531–543. doi: 10.1177/000276486029005003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH, Pleck JH, Ferrera DL. Men and masculinities: Scales for masculinity ideology and masculinity-related constructs. Sex Roles. 1992;27:573–607. doi: 10.1007/BF02651094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs: National Institute of Justice; 2000. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/172837.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Truman DM, Tokar DM, Fischer AR. Dimensions of masculinity: Relations to date rape supportive attitudes and sexual aggression in dating situations. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1996;74:555–562. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1996.tb02292.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, Bosson JK, Cohen D, Burnaford RM, Weaver JR. Precarious manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1325–1339. doi: 10.1037/a0012453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Well S, Kolk AM, Arrindell WA. Cross-cultural validity of the Masculine and Feminine Gender Role Stress scales. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2005;84:271–278. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8403_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega EM, O’Leary KD. Test-retest reliability of the Revised Conflict Tactics scales (CTS2) Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:703–708. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9118-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walby S, Myhill A. New survey methodologies in researching violence against women. British Journal of Criminology. 2001;41:502–522. doi: 10.1093/bjc/41.3.502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DF, Tokar DM, Fischer AR. What are eight masculinity-related instruments measuring? Underlying dimensions and their relations to sociosexuality. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2000;1:98–108. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.1.2.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Graham K. Aggression involving alcohol: Relationship to drinking patterns and social context. Addiction. 2003;98:33–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen EL. Rape, war, and the socialization of masculinity: Why our refusal to give up war ensures that rape cannot be eradicated. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2010;34:538–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01603.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]