Abstract

Background

Antimicrobial stewardship, a key component of an overall strategy to address antimicrobial resistance, has been recognized as a global priority. The ability to track and benchmark antimicrobial use (AMU) is critical to advancing stewardship from an organizational and provincial perspective. As there are few comprehensive systems in Canada that allow for benchmarking, Public Health Ontario conducted a pilot in 2016/2017 to assess the feasibility of using a point prevalence methodology as the basis of a province-wide AMU surveillance program.

Methods

Three acute care hospitals of differing sizes in Ontario, Canada, participated. Adults admitted to inpatient acute care beds on the survey date were eligible for inclusion; a sample size of 170 per hospital was targeted, and data were collected for the 24-hour period before and including the survey date. Debrief sessions at each site were used to gather feedback about the process. Prevalence of AMU and the Antimicrobial Spectrum Index (ASI) was reported for each hospital and by indication per patient case.

Results

Participants identified required improvements for scalability including streamlining ethics, data sharing processes, and enhancing the ability to compare with peer organizations at a provincial level. Of 457 patients, 172 (38%) were receiving at least 1 antimicrobial agent. Beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors were the most common (18%). The overall mean ASI per patient was 6.59; most cases were for treatment of infection (84%).

Conclusions

This pilot identified factors and features required for a scalable provincial AMU surveillance program; future efforts should harmonize administrative processes and enable interfacility benchmarking.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial stewardship, antimicrobial utilization, surveillance

There has been increased attention nationally and globally on improving antimicrobial use (AMU) to limit the trajectory and impact of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [1–3]. One key action to help mitigate AMR is antimicrobial stewardship, which can be defined as coordinated interventions designed to measure use and improve prescribing of antimicrobial agents [4].

In Canada, formal antimicrobial stewardship activities are established in most hospitals as it is an Accreditation Canada Required Organizational Practice for facilities providing inpatient acute care, inpatient cancer, inpatient rehabilitation, and complex continuing care services (CCC) [5]. Although tracking and reporting antibiotic utilization is considered a core component of hospital Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASPs) [1], the literature also consistently identifies the critical role of benchmarking AMU in advancing stewardship programs and addressing AMR [6, 7]. In Canada, in addition to AMR surveillance, select monitoring of AMU is conducted by the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) and the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP), but there are few comprehensive provincial or regional systems that quantify AMU that allow for comparison and benchmarking across institutions [8–10]. For hospital ASPs to determine opportunities for improvement, they should be able to compare themselves to similar care environments. Public Health Ontario (PHO) is a provincial agency that provides scientific and technical advice and support to those working in government, public health, health care, and related sectors. To more effectively plan, strengthen, and evaluate interventions to address AMR in Ontario, PHO requires increased access to robust provincial AMU data.

Point prevalence studies (PPS) aim to determine the incidence of a disease, patient characteristic, or treatment at a point in time and can provide useful epidemiologic data with less resource utilization compared with other surveillance methods. As there is currently no centralized AMU surveillance system in Ontario, PHO conducted a pilot in 2016/2017 with the primary objective of assessing the feasibility of using a point prevalence methodology as the basis of a province-wide AMU surveillance program. Secondary objectives were to identify the prevalence, types, and indications of antimicrobials prescribed in a small sample of Ontario hospitals and to assess the perceived value of the data collected.

Although there have been several large PPS of hospital AMU in the United States [11, 12], Europe [13], Australia [14, 15], and elsewhere [16, 17], PPS of Canadian hospitals are more limited, and are particularly lacking for nonacademic centers [18–20]. To our knowledge, there is also only 1 example of a provincial PPS, conducted in New Brunswick in 2012 [21, 22]. In this Ontario-based feasibility pilot, we aimed to include a broader representation of hospital sizes and types and also explore innovative methodologies for presenting PPS data to increase the utility of the data for benchmarking.

METHODS

Three acute care hospitals participated in this PPS (1 acute teaching, 1 large community, and 1 small community hospital) (Table 1). The definition of hospital type is as per Ontario Hospital Association criteria [23]. This project was approved by Research Ethics and Privacy at PHO and by the research and ethics review board (REB) at each hospital.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Hospitals

| Characteristic | Acute Teaching |

Large Community |

Small Community |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual acute care staysa | 54 805 | 18 263 | 6829 |

| Average length of hospital staya | 6.8 | 4.6 | 6.7 |

| Servicesb | Medical | Medical | Medical |

| Surgical | Surgical | Surgical | |

| Critical care | Critical care | Critical care | |

| Oncology | Oncology | ||

| Transplantation | |||

| No. of eligible patients | 838 | 219 | 71 |

| No. of eligible patients reviewed | 167 | 219 | 71 |

| Presence of a formal antimicrobial stewardship program | Yes | Yes | No |

| Date of point prevalence survey | December 8, 2016 | January 26, 2017 | July 27, 2016 |

aData source: Canadian Institute for Health Information. Available at: https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca. Accessed December 28, 2017.

bServices include those provided to adult acute care patients at the specified hospital.

To obtain an acceptable level of precision in estimating the proportion of inpatients on antibiotics at each hospital while balancing workload, a target sample size of 170 patients per hospital was calculated using a 95% confidence level, an expected proportion of antibiotic use of 40%–60% [11, 16, 17, 19], and a precision level of 7.5%: sample size (n) = (Z2 * P (1 − P))/d2. For hospitals with fewer than 170 eligible inpatients, all eligible inpatients were included. In facilities with more than 170 eligible inpatients, a skip pattern was introduced into the sampling list so that close to 170 inpatients were included.

The surveys were conducted between July 2016 and January 2017. Patients at least 18 years of age and admitted to inpatient acute care beds at the study sites as of 0800 on the survey date were eligible for inclusion; those admitted to outpatient dialysis, psychiatry, ophthalmology, obstetrics, rehabilitation, long-term care, and/or alternate level of care units were excluded. Data were collected for the 24-hour period before and including 0800 on the survey date.

Data collection was performed by hospital staff using an electronic PDF fillable data collection form as close to the survey dates as possible. A detailed data collection guide, appendix, and orientation session was made available to each site before the survey date. At the acute teaching and large community hospital, pharmacists performed the data collection; at the small community hospital, data collection was performed by nurses and validation was conducted by a pharmacist. Data collected included patient age and sex, admitting service, details about AMU, indication for therapy, site of infection, duration of surgical prophylaxis, and setting of infection onset (ie, community or health care/hospital-acquired). In this study, “hospital-acquired” refers to onset of infection 48 hours or more after admission to any hospital and “health care–associated” refers to an infection present at admission or with onset within 48 hours of admission in patients previously hospitalized for 48 hours or more within the previous 90 days or who reside in a long-term care facility. Qualifying antimicrobials included systemic antibacterial agents and antifungal agents. Topical preparations, antiretrovirals, antimicrobials prescribed to treat mycobacterial infections or parasitic infections, demeclocycline, and rifaximin, if prescribed for hepatic encephalopathy, were excluded.

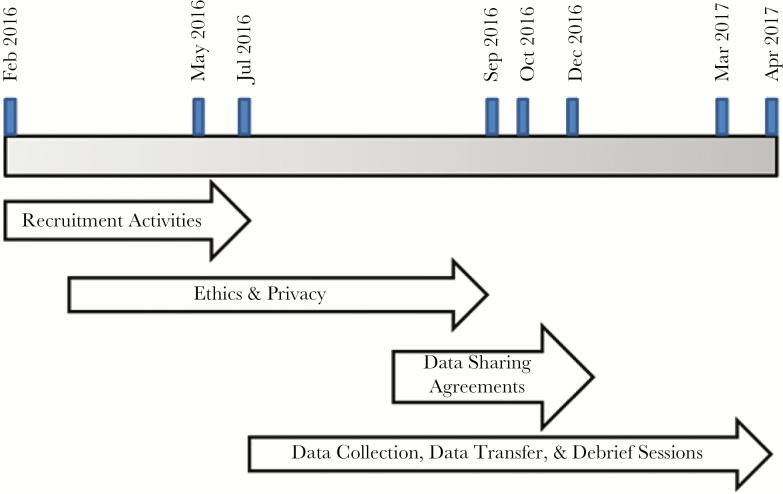

Data were transferred from study sites to PHO using a secure password-protected external SharePoint site (Microsoft 2010) after data sharing agreements between the hospitals and PHO were established. Data sharing agreements required that no personal health information or personal information be transferred to PHO; therefore, all data were de-identified. Individual debrief sessions with each site were then conducted. Predetermined standardized questions about their experience with the data collection process, perceived utility of the data, and overall challenges were used to facilitate discussion. Figure 1 illustrates timelines.

Figure 1.

Timeline of pilot activities.

Data were entered and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (version 14.0; Microsoft, 2007). Data entry was conducted by 1 author (M.L.), 20% was validated by a second author (J.W.), and any discrepancies were resolved in consultation with a third author (B.L. or V.L.). Attempts were made to clarify missing data with hospitals. Prevalence is reported as the proportion of randomized eligible inpatients prescribed at least 1 qualifying antimicrobial to total randomized inpatients. The antimicrobial agents are reported using pharmacologic/therapeutic subgroups based on the World Health Organization [WHO] Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] classification system) [24].

The Antimicrobial Spectrum Index (ASI) was incorporated to enhance PPS metrics [25]. The ASI was developed to categorize antibiotics based on their activity against clinically important organisms to benchmark utilization patterns across hospitals and is intended to provide a measure of the breadth of antibiotic exposure. Although there are several methods in the literature that provide similar measures [12, 26], the ASI was selected as it could be calculated using information already collected as part of the PPS. Mean patient ASI was determined for each hospital and by indication per patient case. Each patient case represents a unique indication for which antimicrobials were prescribed. By definition, patients prescribed only antivirals and/or antifungals were excluded from this calculation. Appendix 1 includes the ASI score for each antibiotic used to calculate the total ASI.

RESULTS

Feedback on PPS Process

Overall, participants felt that the data collection tools provided by PHO were straightforward but that an online portal for data entry and submission would be strongly preferred. The estimated time to collect data was between 2 and 5 minutes per patient. All hospitals felt that the ethics review and data sharing agreement processes were very resource intensive, and some questioned whether these would be mandatory for this type of surveillance if conducted outside of a research study.

Perceived usefulness of the PPS data for internal purposes was greatest for the small community hospital, which does not yet have a formal ASP. One site attempted to incorporate appropriateness into their review to increase internal usefulness but found it too time consuming to complete within the time frame for submitting the PPS data. All sites emphasized that it would be very beneficial to compare their AMU data with other hospitals, particularly peer organizations and at a regional/provincial level.

Antimicrobial Utilization Data

On the study dates, 457 patients in 3 Ontario hospitals were surveyed. Seventy-two percent of all patients included in the surveys were ≥61 years old, and just over half were female (50%). Overall, 172 (38%) patients were receiving at least 1 antimicrobial agent: 67/167 (40%) at the acute teaching hospital, 69/219 (32%) at the large community hospital, and 36/71 (51%) at the small community hospital. Of patients prescribed antimicrobials, 48/172 (28%) patients were receiving multiple antimicrobial agents. AMU was most prevalent in patients admitted under a medical service (47%), and the majority of patients receiving antimicrobials were in the ≥61 age group (71%) (Table 2). Sixty-one percent of antimicrobials were administered parenterally.

Table 2.

AMU in Ontario Hospitals: Characteristics of Patients Receiving Antimicrobials

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 172), n (%) | Acute Teaching (n = 67), n (%) | Large Community (n = 69), n (%) | Small Community (n = 36), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| 18–40 | 12 (7) | 7 (10) | 2 (3) | 3 (8) |

| 41–60 | 38 (22) | 20 (30) | 11 (16) | 7 (19) |

| ≥61 | 122 (71) | 40 (60) | 56 (82) | 26 (72) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 84 (49) | 38 (57) | 33 (48) | 13 (36) |

| Female | 88 (51) | 29 (43) | 36 (52) | 23 (64) |

| Service | ||||

| Medical | 80 (47) | 22 (33) | 33 (48) | 25 (70) |

| Surgical | 47 (27) | 20 (30) | 22 (32) | 5 (14) |

| Critical care | 24 (14) | 8 (12) | 10 (14) | 6 (17) |

| Oncology/hematology/transplant | 21 (12) | 17 (25) | 4 (6) | — |

Abbreviations: AMU, antimicrobial use.

A total of 232 antimicrobials were prescribed; beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors were the most common class (18%), followed by first-generation cephalosporins (17%) and third-generation cephalosporins (16%). Most first-generation cephalosporin orders (86%) were cefazolin, the majority of which were prescribed for surgical prophylaxis (71%). The overall mean ASI per patient was 6.59; the acute teaching hospital had the highest mean ASI per patient, indicating that the breadth of antibiotic spectrum used per patient was broadest at this site relative to the others (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Antimicrobial Class Use in Ontario Hospitals

| Antimicrobial Class | Overall (n = 232), n (%) | Acute Teaching (n = 104), n (%) | Large Community (n = 81), n (%) | Small Community (n = 47), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillins | ||||

| Beta-lactamase resistant | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | — |

| Beta-lactamase sensitive | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | — |

| Extended-spectrum | 6 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations | ||||

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | 18 (8) | 4 (4) | 11 (14) | 3 (6) |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 23 (10) | 7 (7) | 9 (11) | 7 (15) |

| Cephalosporins | ||||

| First-generation | 40 (17) | 11 (11) | 22 (27) | 7 (15) |

| Second-generation | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (4) |

| Third/fourth-generation | 37 (16) | 13 (13) | 16 (20) | 8 (17) |

| Carbapenems | 11 (5) | 8 (8) | — | 3 (6) |

| Fluoroquinolones | ||||

| Second-generation | 7 (3) | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | — |

| Third-generation | 11 (5) | 6 (6) | 2 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Sulfonamides and/or trimethoprim | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | — | — |

| Glycopeptides | 20 (9) | 13 (13) | 3 (4) | 4 (9) |

| Macrolides | 9 (4) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (9) |

| Aminoglycosides | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | — | — |

| Metronidazole | 17 (7) | 5 (5) | 8 (10) | 4 (9) |

| Neuraminidase inhibitors | 3 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | — |

| Other antivirals | 7 (3) | 7 (7) | — | — |

| Triazole derivatives | 9 (4) | 9 (9) | — | — |

| Other antibacterials | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | — | — |

| Mean Antibiotic Spectrum Index per patient | 6.59 | 8.00 | 5.19 | 6.94 |

Other antivirals: acyclovir, valacyclovir. Other antibacterials: daptomycin.

Table 4 describes indications for AMU and mean ASI per patient case. There were 182 infectious indications (patient cases) documented among the 172 patients included in the study. The majority of patient cases were for treatment of active infection (84%); of these, respiratory (32%), skin and soft tissue (12%), and urinary tract infections (11%) together accounted for more than half of all cases. The setting of infection acquisition was mostly community-acquired (53%) vs hospital-acquired or health care–associated (44%); a small number were unknown (3%). The overall mean ASI was highest for treatment of sepsis and intra-abdominal infections and lowest for urinary tract and gastrointestinal infections. Fifteen percent of patient cases were surgical prophylaxis, most frequently for orthopedic procedures. Of the patients receiving surgical prophylaxis, more than half (70%) received prophylactic antimicrobials postoperatively, with 11% extending beyond 24 hours.

Table 4.

Mean Antibiotic Spectrum Index per Patient Case

| Overall | Acute Teaching | Large Community | Small Community | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication | Patient Cases (n = 182), n (%) |

Mean ASI/Patient Case | Patient Cases (n = 70), n (%) | Mean ASI/Patient Case |

Patient Cases (n = 70), n (%) | Mean ASI/Patient Case |

Patient Cases (n = 42), n (%) | Mean ASI/Patient Case |

| Treatment of infection | 152 (84) | — | 60 (86) | — | 55 (79) | — | 37 (88) | — |

| Respiratory | 59 (32) | 6.90 | 16 (23) | 8.31 | 27 (39) | 5.85 | 16 (38) | 7.25 |

| Urinary | 20 (11) | 5.80 | 11 (16) | 6.45 | 4 (6) | 4.00 | 5 (12) | 5.80 |

| Skin/soft tissue | 22 (12) | 6.36 | 9 (13) | 7.44 | 7 (10) | 5.00 | 6 (14) | 6.33 |

| Gastrointestinal | 9 (5) | 4.33 | 4 (6) | 4.25 | 2 (3) | 5.00 | 3 (12) | 4.00 |

| Bone/joint | 7 (4) | 6.71 | 3 (4) | 8.67 | 3 (4) | 3.33 | 1 (2) | 11.00 |

| Intra-abdominal | 7 (4) | 8.85 | 4 (6) | 10.50 | 2 (3) | 6.00 | 1 (2) | 8.00 |

| Sepsis | 7 (4) | 9.71 | 3 (4) | 12.00 | 3 (4) | 6.33 | 1 (2) | 13.00 |

| Other | 21 (12) | 7.42 | 10 (14) | 7.40 | 7 (10) | 7.00 | 4 (10) | 8.25 |

| Surgical prophylaxis | 27 (15) | — | 7 (10) | — | 15 (21) | — | 5 (12) | — |

| Orthopedic | 13 (7) | 5.31 | 1 (1) | 3.00 | 8 (11) | 6.00 | 4 (10) | 4.50 |

| Intra-abdominal | 5 (3) | 6.00 | — | — | 4 (6) | 4.00 | 1 (2) | 14.00 |

| Neurosurgery | 2 (1) | 4.00 | 2 (3) | 4.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Head/neck | 2 (1) | 4.00 | 2 (3) | 4.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Urologic | 2 (1) | 3.00 | — | — | 2 (3) | 3.00 | — | — |

| Transplant | 1 (<1) | 3.00 | 1 (1) | 3.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Plastic surgery | 1 (<1) | 3.00 | — | — | 1 (1) | 3.00 | — | — |

| Vascular | 1 (<1) | 3.00 | 1 (1) | 3.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Nonsurgical prophylaxis | 3 (2) | 5.00 | 3 (4) | 5.00 | — | — | — | — |

Abbreviation: ASI, Antibiotic Spectrum Index.

DISCUSSION

Although the importance of benchmarking AMU is clearly articulated in the literature and by the antimicrobial stewardship community in Canada [9, 10], there is currently no centralized system for collecting or synthesizing hospital AMU data nationally or in Ontario. To determine the feasibility of a point prevalence methodology to support provincial AMU surveillance activities, PHO completed a pilot involving 3 hospitals of differing sizes.

In this feasibility study, several success factors and features critical for a future large-scale AMU surveillance program emerged. First, a streamlined and simplified research ethics, privacy, and data sharing agreement process is needed. From our provincial organization’s perspective, the time and effort that would be required to negotiate ethics review and data sharing agreements for all hospitals in Ontario, in addition to the agency’s ethics and privacy approval, were identified as the most significant barrier to scaling this initiative on a provincial level. As this initiative was positioned as a research study, approval from PHO Research and Ethics, PHO Privacy, and local REB was deemed necessary. Although PHO provided overall study coordination, a substantial work effort was required by hospitals in relation to local research ethics, privacy, and legal processes for data sharing agreements. This is particularly problematic for smaller sites that do not have an in-house REB or legal counsel. To mitigate delays for any future provincial AMU surveillance initiatives, we propose alignment with previous national PPS conducted by CNISP, which did not require institutional REB review in most hospitals because activities of this nature were viewed as part of the mandate of hospital infection prevention and control programs and not human research [19]. Rather than relying on local privacy processes that may not be harmonized, other mechanisms to ensure that privacy policies, procedures, and controls are in place may be more effective. For example, in the United States, enrollment in the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance system that includes AMU, obliges the facility/group administrator to abide by specific “Rules of Behavior” that explicitly outline the roles and responsibilities of users with respect to information privacy and security standards [27]. Data sharing agreements, if required, should be standardized in the future to expedite review and sign-off; in this pilot, PHO proposed a template; however, customization was required at 2 sites. The impact of these asynchronous and lengthy administrative processes was a long-time span between the first and last survey dates, and as a result, seasonality likely contributed to some of the observed variability in AMU.

A number of desired features for a large-scale AMU surveillance program were identified from this pilot. From a technical perspective, the ease of data collection and transfer will be a major determinant in site participation. In this pilot, sites documented data using an electronic fillable PDF form and uploaded these files to a secure Sharepoint site for PHO to download and record into Excel for analysis, a process that created significant workload and potential for transcription errors. Unless a secure online portal can be implemented, an AMU surveillance program will not be scalable. Ideally, hospitals contributing data should also be able to access comparisons on demand from a central electronic source and be able to filter and sort for maximum utility.

The ability to compare data between hospitals and at a regional and/or provincial level is a highly anticipated feature for an AMU surveillance program. The overall prevalence of AMU (38%) in this study is similar to the 2009 CNISP PPS (40%) [19] but lower than that observed in a recent PPS of hospitals in the United States (50%) [11]. Regional differences in overall AMU and AMU by class relative to the New Brunswick PPS data have also been observed [21, 22]. However, the utility of this comparison is limited, as this pilot PPS involved only 3 hospitals of varying size. A larger-scale PPS has the potential to identify trends or signals that may be actionable by local ASPs or by our provincial organization. As demonstrated in our pilot, hospital characteristics such as type and presence or absence of a formal ASP can influence AMU patterns. To maximize comparability at a regional/provincial level, inclusion of additional hospital information, such as locally available subspecialties, and patient characteristics, such as patient acuity and/or illness severity, should be considered to model risk adjustment. Whereas some PPS have included assessment of AMU appropriateness using hospital guidelines [28] and/or algorithms that require individual patient case review [21, 22, 29], this can be challenging from a workload perspective and may not be feasible for a large-scale initiative. In future work, it will be helpful to determine reliable and accurate ways to evaluate the appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing while being mindful of resource limitations.

Recently, there have been some examples in the literature of methods to determine the breadth of antibiotic exposure [12, 26], including the ASI [25]. In our pilot, we attempted to enhance conventional PPS metrics by including ASI normalized by patient cases. Interestingly, mean ASI per patient case in our study was similar to that reported by Gerber et al. when classified by indication even though the Gerber study used antibiotic day as a denominator. For example, the mean ASI per patient case in our pilot is similarly narrow for respiratory infections in our study (6.63 per patient case) as for pneumonia in the ASI paper (6.3 per antibiotic day). Although we selected ASI because it could easily be determined without collecting additional information in our PPS, we recognize that there is no single ideal methodology.

In conclusion, our pilot PPS involving 3 hospitals of differing sizes in Ontario, Canada, identified several success factors and features critical for a scalable AMU surveillance program. Future initiatives should harmonize research ethics, privacy, and data sharing processes. Features that will encourage participation such as an online data entry platform and access to interfacility risk-adjusted benchmarking are also desirable for a regional or provincial program.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Appendix Table 1. Antibiotic Spectrum Index

| Antibiotic | ASI Score |

|---|---|

| Cloxacillin | 1 |

| Amoxicillin | 2 |

| Ampicillin | 2 |

| Cephalexin | 2 |

| Erythromycin | 2 |

| Metronidazole | 2 |

| Penicillin | 2 |

| Cefazolin | 3 |

| Cefixime | 3 |

| Azithromycin | 4 |

| Ceftazidime | 4 |

| Cefuroxime | 4 |

| Clarithromycin | 4 |

| Clindamycin | 4 |

| Piperacillin | 4 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 4 |

| Cefotaxime | 5 |

| Cefoxitin | 5 |

| Ceftriaxone | 5 |

| Colistin | 5 |

| Daptomycin | 5 |

| Gentamicin | 5 |

| Minocycline | 5 |

| Tobramycin | 5 |

| Vancomycin | 5 |

| Amikacin | 6 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 6 |

| Cefepime | 6 |

| Linezolid | 6 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8 |

| Piperacilln-tazobactam | 8 |

| Ertapenem | 9 |

| Levofloxacin | 9 |

| Meropenem | 10 |

| Moxifloxacin | 10 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 11 |

| Tigecycline | 13 |

Adapted from: Gerber JS, Hersh AL, Kronman MP, et al. Development and application of an antibiotic spectrum index for benchmarking antibiotic selection patterns across hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2017; 38(8):993–7.25

References

- 1. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/implementation/core-elements.html. Updated 2017. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Public Health Agency of Canada. The Canadian nosocomial infection surveillance program. Available at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nois-sinp/survprog-eng.php. Updated 2012. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/193736/1/9789241509763_eng.pdf?ua=1. Updated 2015. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Policy statement on antimicrobial stewardship by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012; 33:322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Accreditation Canada. Required organizational practices: handbook 2016. Version 2. Available at: https://accreditation.ca/sites/default/files/rop-handbook-2016v2.pdf. Updated 2015. Accessed 21 Feb 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Septimus E. Antimicrobial stewardship-qualitative and quantitative outcomes: the role of measurement. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2014; 16:433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ibrahim OM, Polk RE. Antimicrobial use metrics and benchmarking to improve stewardship outcomes: methodology, opportunities, and challenges. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2014; 28:195–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grant J, Saxinger L, Patrick D.. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial utilization in Canada. Available at: http://www.researchid.com/pdf/AMMIReportAug22-with-PubNote.pdf. Updated 2014. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. The Communicable and Infectious Disease Steering Committee Task Group on Antimicrobial Use Stewardship. Final report to the Public Health Network Council April 2016. Available at: http://www.phn-rsp.ca/pubs/anstew-gestan/pdf/pub-eng.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed 20 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. HealthCareCAN, National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. Putting the pieces together: a national action plan on antimicrobial stewardship. Available at: http://www.healthcarecan.ca/wp-content/themes/camyno/assets/document/ Reports/2016/HCC/EN/Putting%20the%20Pieces%20Together%20-%20Final%20Version.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. ; Emerging Infections Program Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use Prevalence Survey Team Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May–September 2011. JAMA 2014; 312:1438–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stenehjem E, Hersh AL, Sheng X, et al. Antibiotic use in small community hospitals. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:1273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zarb P, Coignard B, Griskeviciene J, et al. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) pilot point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use. Euro Surveill 2012; 17:20316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antimicrobial prescribing practice in Australian hospitals: results of the 2015 national antimicrobial prescribing survey. Available at: https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/d820f98f/files/uploaded/Antimicrobial-prescribing-practice-in-Australian-hospitals-Results-of-the-2015-National-Antimicrobial-Prescribing-Survey.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Osowicki J, Gwee A, Noronha J, et al. Australia-wide point prevalence survey of the use and appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing for children in hospital. Med J Aust 2014; 201:657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li C, Ren N, Wen X, et al. Changes in antimicrobial use prevalence in China: results from five point prevalence studies. PLoS One 2013; 8:e82785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thu TA, Rahman M, Coffin S, et al. Antibiotic use in Vietnamese hospitals: a multicenter point-prevalence study. Am J Infect Control 2012; 40:840–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gravel D, Taylor G, Ofner M, et al. ; Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program Point prevalence survey for healthcare-associated infections within Canadian adult acute-care hospitals. J Hosp Infect 2007; 66:243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taylor G, Gravel D, Saxinger L, et al. ; Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program Prevalence of antimicrobial use in a network of Canadian hospitals in 2002 and 2009. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2015; 26:85–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee C, Walker SA, Daneman N, et al. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilization in a Canadian tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2015; 5:143–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brideau-Laughlin D, Girouard G, Levesque M, et al. Executive summary: A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial use: benchmarking and patterns of use to support antimicrobial stewardship efforts. Available at: http://www.vitalitenb.ca/sites/default/files/documents/medecins/pps_executive_summary_v_3.pdf. Updated 2013. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brideau-Laughlin D. A Point-Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Utilisation Within New Brunswick Hospitals to Focus Antimicrobial Stewardship Efforts and Decrease Low-Value Care [Master’s thesis]. Montreal, Canada: University of Montreal; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Canadian Institute for Health Information, Government of Ontario, Ontario Hospital Association, Hospital Report Research Collaborative. Hospital report acute care 2007. Available at: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/OHA_Acute07_EN_final_secure.pdf. Updated 2007. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD index 2017. Available at: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Updated 2016. Accessed 26 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gerber JS, Hersh AL, Kronman MP, et al. Development and application of an antibiotic spectrum index for benchmarking antibiotic selection patterns across hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2017; 38:993–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Madaras-Kelly K, Jones M, Remington R, et al. Development of an antibiotic spectrum score based on Veterans Affairs culture and susceptibility data for the purpose of measuring antibiotic de-escalation: a modified Delphi approach. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014; 35:1103–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Healthcare Safety Network facility/group administrator rules of behaviour. Version 2.0. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/FacAdminROB.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed 20 Sept 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aldeyab MA, Kearney MP, McElnay JC, et al. ; ESAC Hospital Care Subproject Group A point prevalence survey of antibiotic prescriptions: benchmarking and patterns of use. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011; 71:293–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willemsen I, Groenhuijzen A, Bogaers D, et al. Appropriateness of antimicrobial therapy measured by repeated prevalence surveys. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51:864–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]