Abstract

Nitrogenase is the enzyme that reduces atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) in biological systems. It catalyzes a series of single-electron transfers from the donor iron protein (Fe protein) to the molybdenum–iron protein (MoFe protein) that contains the iron–molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co) sites where N2 is reduced to NH3. The P-cluster in the MoFe protein functions in nitrogenase catalysis as an intermediate electron carrier between the external electron donor, the Fe protein, and the FeMo-co sites of the MoFe protein. Previous work has revealed that the P-cluster undergoes redox-dependent structural changes and that the transition from the all-ferrous resting (PN) state to the two-electron oxidized P2+ state is accompanied by protein serine hydroxyl and backbone amide ligation to iron. In this work, the MoFe protein was poised at defined potentials with redox mediators in an electrochemical cell, and the three distinct structural states of the P-cluster (P2+, P1+, and PN) were characterized by X-ray crystallography and confirmed by computational analysis. These analyses revealed that the three oxidation states differ in coordination, implicating that the P1+ state retains the serine hydroxyl coordination but lacks the backbone amide coordination observed in the P2+ states. These results provide a complete picture of the redox-dependent ligand rearrangements of the three P-cluster redox states.

Keywords: oxidation-reduction (redox); metalloprotein; nitrogenase; enzyme structure; computational biology; nitrogen fixation; nitrogen reduction; P-cluster of MoFe protein; poised states; redox mediators; redox-dependent ligand exchange, [8Fe-7S] cluster

Introduction

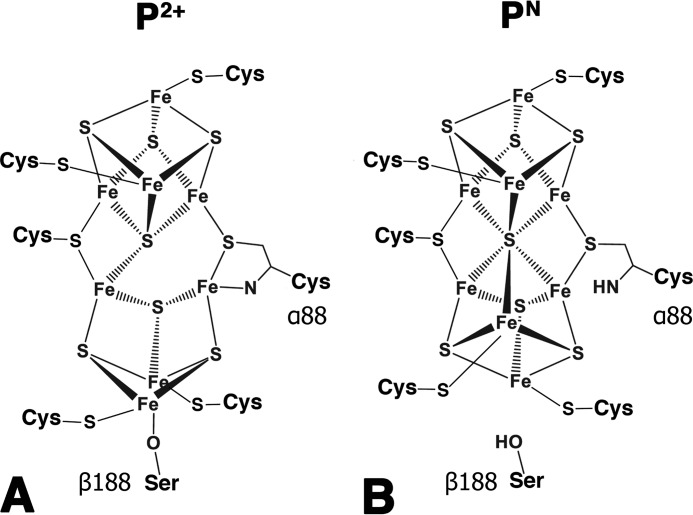

Nitrogenase is the enzyme responsible for the multiple-electron reduction of atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) in biological systems (1). This complex oxygen-sensitive metalloprotein orchestrates a series of ATP-dependent single-electron transfers from the donor iron protein (Fe protein)5 to the catalytically active molybdenum–iron protein (MoFe protein) (2). During catalysis, the process of electron delivery to the active site involves two types of electron transfer events: one event is the intermolecular electron transfer between the [4Fe-4S] cluster of the Fe protein and the P-clusters of the MoFe protein, and the other is the intramolecular electron transfer between the two P-clusters and two [7Fe-9S-C-Mo-homocitrate] iron–molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co) active sites within the MoFe protein (3, 4). Recent work has helped delineate the order of these electron transfer events with a proposed “deficit-spending” model (5). This model postulates that the interaction of the Fe protein and the MoFe protein elicits conformational changes that facilitate an initial “slow” and conformationally gated electron transfer step event between the P-cluster and the FeMo-co (5, 6). This event leaves the P-cluster with a “deficit” of one electron (P1+) relative to the all-ferrous resting (PN) state. This deficit is then repaid by a second, faster intermolecular electron transfer event from the reduced [4Fe-4S]1+ cluster in the Fe protein to the P1+-cluster, restoring the PN state (5). This fast step is a direct electron transfer step and takes place at rates greater than 1700 s−1, which could explain why the P1+ state is difficult to observe during turnover (7). Thus, the deficit-spending model postulates that major conformational changes occur during catalysis, but the conformational changes that regulate the gated unidirectional electron flow are likely short-lived. The mechanistically relevant P1+ state has been observed spectroscopically in native and variant MoFe proteins (8–10). However, this state was only achievable using electrochemical mediators. Previous structural work has revealed two distinct conformations of the P-cluster that have been assigned to the PN resting state and the P2+ oxidized state (Fig. 1) (11, 12). The structures differ in the ligation of P-cluster iron ions such that the P2+ oxidized state possesses two noncysteinyl protein ligands where a serine side chain oxygen (βSer188 according to the MoFe protein numbering from Azotobacter vinelandii) and a peptide backbone amide nitrogen (αCys88) replace two of the ligands of the hexacoordinated central sulfide present in the PN state (Fig. 1). The P2+ conformation is typically seen in native MoFe protein structures due to the gradual oxidation of reductants present in the precipitant solution during crystallization. The PN state was generated by reducing MoFe protein crystals with excess sodium dithionite just prior to flash cooling in a manner similar to the aforementioned spectroscopic studies (11, 13).

Figure 1.

Presumed structural representations of the P2+ (A) and PN (B) redox states of the P-cluster, highlighting differences in ligation.

The role of alternative electron transfer mechanisms involving direct oscillations between the PN and P2+ states has been investigated previously (14); however, various lines of evidence indicate that only single-electron transfer events occur between the reduced PN state of the P-cluster and the active site, suggesting that the P1+/PN couple is the predominant oscillation of the P-cluster under turnover conditions (15). The structures of the PN and P2+ states have been determined previously, but the structure of the intermediate P1+ state is needed for defining the cycle of redox-dependent structural changes that occur during catalysis. To elucidate the structure of the P1+ state, structures of the nitrogenase MoFe protein were solved for crystals poised at defined oxidation-reduction potentials with redox mediator solutions in an electrochemical cell. In addition, computational analysis were performed to evaluate the ligation of P-cluster by αCys88 and βSer188 side chains corresponding to three (P2+/P1+/PN) oxidation states of P-cluster observed for MoFe protein. Together the results reveal a new state of the P-cluster with coordination distinct from the previously characterized P2+ and PN oxidation states.

Results

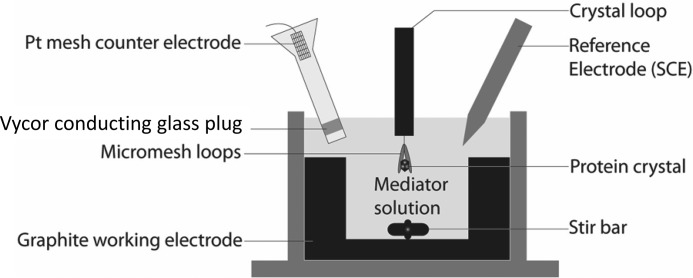

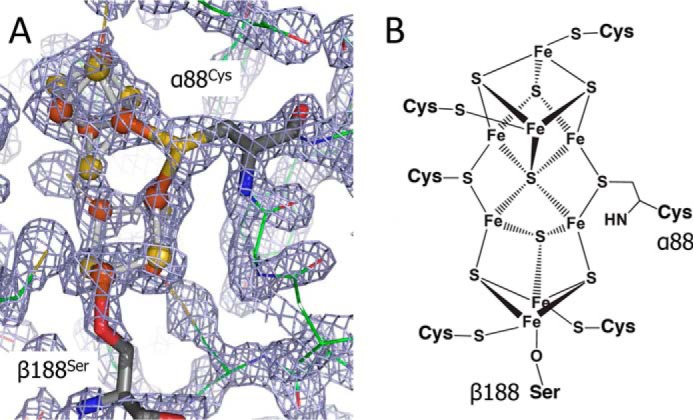

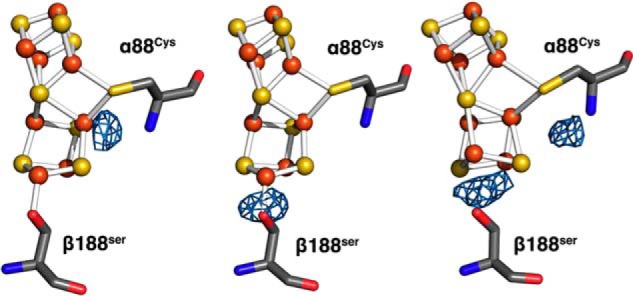

Crystals of MoFe protein were poised at different potentials in an electrochemical cell containing mother liquor supplemented with redox-active dyes (Fig. 2). Constant stirring maintained a homogenous charge throughout the solution, and a “sandwich-loop” crystal mounting technique was developed to prevent the crystals from washing off the loop during electrochemical poising. After 1 h of incubation in the electrochemical cell at known potential, the nitrogenase crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The poised crystals in the presence of redox mediators were highly sensitive to X-rays regardless of potential through the range of poised samples. The plate morphology of the crystals prevented collecting complete data sets in all cases due to the extremely rapid decay observed when data collection was attempted across the long angle of the crystals. Despite being only able to obtain partial data sets (∼60%), it was possible to reproduce our previously published results and confirm structural differences between PN and P2+ states (Tables S1 and S2). Crystals of MoFe protein treated with flavin mononucleotide and held at −238 mV versus normal hydrogen electrode revealed a novel intermediate structure distinct from the PN and P2+ structures in ligation, which was assigned as the P1+ state. Feature-enhanced electron density maps (16) were of sufficient quality to clearly distinguish the observed intermediate P-cluster structural state from the previously reported P-cluster PN and P2+ structures (Fig. 3 and Table S2). The structural differences observed in comparing the assigned PN, P1+, and P2+ oxidation states are manifested solely in changes in cluster ligation. Interestingly, the new state, assigned as the P1+ state, was only observed on one αβ dimer of the 2-fold symmetric α2β2 heterotetrameric MoFe protein; the P-cluster in the second αβ dimer was found to be in the P2+ oxidation state. The P1+ state structure has a ligand arrangement intermediate between the PN and P2+ states. The P1+ state possesses serine coordination to iron but lacks the amide nitrogen ligation seen in the P2+ state. Fo − Fc difference density analysis experiments were carried out between the P1+ and PN, P1+ and P2+, and PN and P2+ structures to provide additional support for the new structural state. (Fig. 4). The observation that the amide nitrogen ligand is exchanged by ligation to the central sulfur prior to the serine oxygen coordination in the redox progression during reduction can be rationalized from the perspective of the hard/soft and acid/base theory because nitrogen is a slightly harder and weaker ligand than oxygen, and its affinity would be further decreased on reduction of the metal to be ligated. Thus, the suite of P-cluster structures provides evidence to suggest that the first oxidizing equivalent changes the structure of the iron ion near the βSer188 and may oxidize this iron first. The second oxidizing equivalent would then oxidize the iron ion atom near the αCys88.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the crystal potential poising apparatus. Crystals were submerged in a stirred solution held at constant potential for 1 h prior to flash cooling in liquid nitrogen to poise them in distinct structural states. SCE, saturated calomel electrode.

Figure 3.

A, FEM calculated using phenix.fem showing P-cluster in P+1 state. P-cluster is shown in stick and balls, αCys88 and βSer188 are shown in sticks, and MoFe protein is shown in lines. FEM is contoured to 1.5σ. B, structural representation of the P1+ redox state of the nitrogenase P-cluster deduced from the present studies.

Figure 4.

Fo − Fc difference electron density analysis of electrochemically poised P-cluster structures. The P1+ model is shown (left) with Fo − Fc (P1+ − P2+) difference electron density contoured to 5σ. The P1+ model is shown (middle) with Fo − Fc (P1+ − PN) difference electron density contoured to 2σ (peak still clearly present at 3σ). The PN model is shown (right) with Fo − Fc (PN − P2+) difference electron density contoured to 3σ, highlighting the differences between the two-electron reduced and oxidized poised structures.

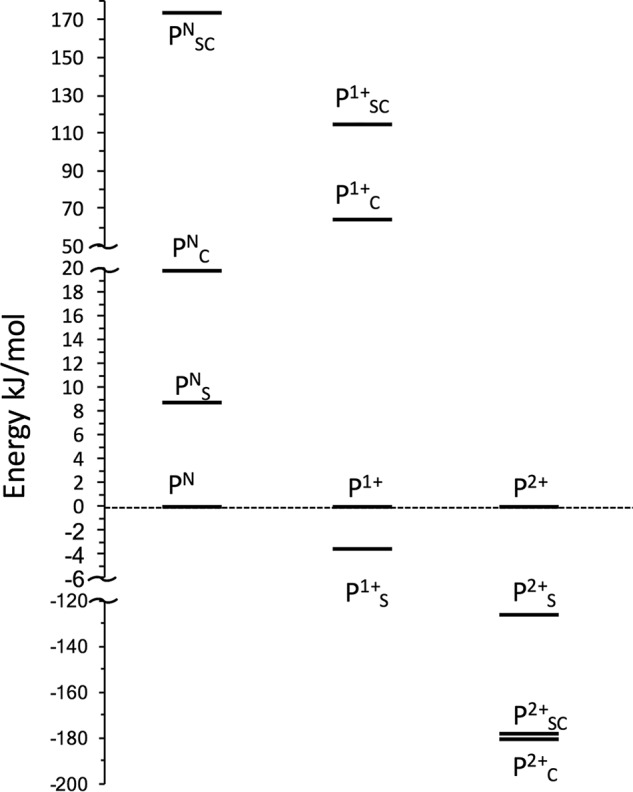

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed for the three oxidation states of the P-cluster to evaluate the relative sequence of binding of the serine and amide ligands. The energy ordering of the possible ligation forms for every given oxidation state is reported in Fig. 5. Consistent with the experimental evidence, in the lowest-energy PN state structure, both αCys88 and βSer188 are not bound. The PNS is 9 kj/mol higher then PN, and PNC state is 11 kJ/mol higher then PNS (It is 20 kj/mol higher then PN). Only PNS is serine-ligated. In stark contrast, the doubly ligated PNSC isomer is 174 kJ/mol above the nonligated PN form. Oxidation of PN by one or two electrons dramatically alters the ligation preference of the cluster. The βSer188-ligated state, P1+S, is calculated to be the most stable one-electron oxidized form of the P-cluster, −4 kJ/mol lower in energy than the nonligated form, whereas the αCys88-ligated form, P1+C, and doubly ligated P1+SC form are far higher in energy. Double oxidation of the P-cluster (P2+) favors binding of both αCys88 and βSer188 with the doubly ligated P2+SC being significantly more stable than the P2+C state, by 55 kJ/mol, and only slightly less stable, by 2 kJ/mol, than P2+S. When more accurate treatment of the zero-point correction is utilized, the order of the P2+S and P2+SC inverts with P2+SC being more stable by 37 kJ/mol (Fig. S2). Unfortunately, due to numerical issues, this approach was not available for all states.

Figure 5.

Free energy ordering of the possible ligation forms of the P-cluster in the PN, P1+, and P2+ states. The subscripts “S” and “C” indicate Ser- and Cys-bound P-cluster, respectively. For each state, all of the energy is relative to the nonligated cluster. Note the change of the energy scale axis that is adopted for clarity of visualization of all the various species in the same graph.

Taken as a whole, these calculations confirm that the serine side chain has a higher binding affinity than the Cys backbone amide nitrogen and that the serine side chain preferentially binds to the P-cluster after the first oxidation event (P1+), whereas double oxidation (P2+) greatly increases the binding affinities, resulting in the preferential formation of the doubly ligated form of the P-cluster.

Discussion

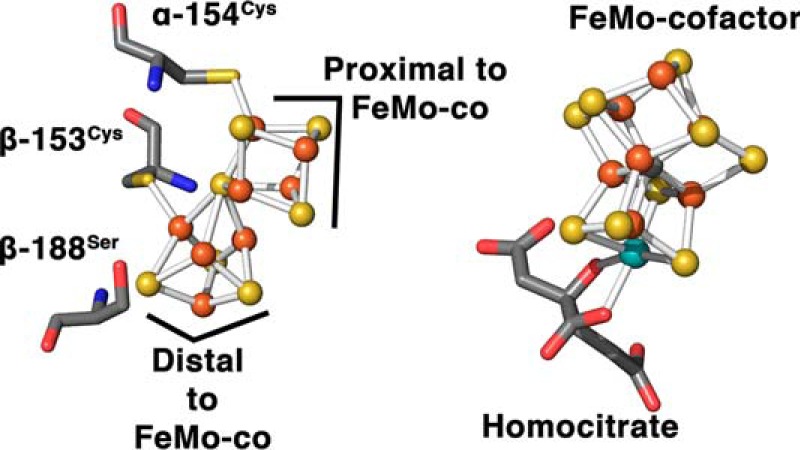

This newly visualized P1+ state is compatible with the proposed deficit-spending mechanism and demonstrates a redox-mediated ligand-exchange mechanism for possibly regulating electron flow for the P1+/PN redox couple. Previous mutagenesis studies targeting the βSer188 P-cluster ligand have utilized the introduction of a stronger ligand, such as cysteine, or removal of coordination by glycine substitution to stabilize the P-cluster in the P1+ and PN states by shifting the resting potential of the cluster −90 and +60 mV, respectively (4, 17). Interestingly, these amino acid substitutions confer lower specific activities to the variants by disrupting a key exchangeable ligand (4, 5). These observations add support to our P1+ assignment of this structure and the prominence of a ligand-exchange mechanism in nitrogenase catalysis. Recently, we have shown that amino acid substitutions near the proximal side of the P-cluster cubane relative to FeMo-co (Fe1–4 based on the Protein Data Bank numbering scheme), such as βTyr98 → His, βPhe99 → His, and αTyr64 → His, generate protein variants that are capable of being reduced by low-reduction potential mediators, which have Eu(II) ligated to polyaminocarboxylate ligands, whereas substitutions near the Fe5–8 cubane (distal side to FeMo-co) do not show this behavior (18, 19). Analyzing this information in light of our current finding, we can assign directional character to the P-cluster. Here, based on the substitution studies, the proximal side of the cubane relative to FeMo-co would be involved in the electron transfer between the P-cluster and FeMo-co during the slow step, whereas the distal cubane undergoes structural conformational changes to accommodate the loss of an electron from the P-cluster (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Ball and stick representations of the P-cluster and FeMo cofactor, highlighting the orientation of the P-cluster cubanes with respect to the FeMo cofactor.

We have also recently shown that electron transfer between the Fe protein and the MoFe protein precedes ATP hydrolysis (20). Conformational changes within the P-cluster of the MoFe protein during the deficit-spending events could potentially serve as triggers for the initiation of the ATP-hydrolysis step within the Fe protein. This would result in the Fe protein cycle of electron transfer being a conformationally controlled series of events. Furthermore, it has been previously suggested that the Fe protein–MoFe protein interaction could cause the βSer188 to transiently coordinate to the P-cluster, creating an activated P-cluster state (designated PNS) with a lowering of the potential to facilitate electron transfer between the P-cluster and FeMo cofactor (5). Consistent with this hypothesis, the present DFT calculations predict the ligated PNS state to be only 9 kJ/mol higher in energy than the PN state and therefore potentially accessible upon slight distortion of the P-cluster environment.

The one-electron ligand exchange also raises the possibility of the involvement of the P-cluster in a proposed proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) mechanism in nitrogenase. The βSer188 hydroxyl and αCys88 amide would presumably be protonated when not coordinated to the P-cluster. Potential proton donor/acceptors are within hydrogen-bonding distance of the βSer188 hydroxyl group (an ordered water molecule) and the αCys88 backbone amide (αGlu153 side chain). Sequential hydride formation has been postulated as part of the catalytic cycle (21); therefore, the single redox P1+/PN couple fits well into the most recent proposed deficit-spending mechanism. Additionally, previous spectroscopic studies have also shown residues around the distal side of the P-cluster cubane (relative to FeMo-co) to be involved in PCET (17). Although this unique iron–sulfur cluster has been shown to undergo unprecedented redox-mediated structural changes, a complete understanding of the unidirectional PCET is difficult without more information regarding the complex and dynamic global conformational changes that occur when the Fe protein interacts with the MoFe protein. Current structural techniques have failed to provide details of these transient global conformational changes. By utilizing a new redox crystallography approach, complemented by DFT calculations, we are now able to populate some of these difficult to obtain transient states and piece together the details of one of nature's most enigmatic catalytic cycles. The work presented here also has relevance to probing electron flow and redox-mediated structural changes in numerous metalloprotein systems, providing possible insights into biological electron transfer.

Experimental procedures

Purification and crystallization of MoFe protein

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Fischer Scientific and were used without further purification. WT MoFe protein from A. vinelandii was purified under strict anaerobic conditions according to protocols described previously (22). All proteins were obtained at greater than 95% purity, confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis using Coomassie Blue staining, and demonstrated maximal specific activity (greater than 2,000 nmol of H2/min/mg of MoFe protein). Handling of proteins was done in septum-sealed serum vials under an argon atmosphere. All transfer of gases and liquids was done using gastight syringes. Protein crystals were grown by capillary batch diffusion in a 100% N2 atmosphere MBRAUN glove box with precipitant solutions reported previously (23).

Poising crystals of FeMo protein with redox mediators

Crystals were harvested anaerobically under an argon stream and immobilized on pins using a novel “sandwich” loop designed to prevent the crystals from washing away during electrochemical studies. Two micromesh loops (MiTeGen LLC, Ithaca, NY) were affixed on top of each other to the same pin, and a small piece of monofilament was placed in between to separate them. Crystals were positioned between the loops, and the monofilament was then removed to apply tension from the loops to secure the crystals. The immobilized crystals were immediately submerged in an electrode solution mimicking the precipitant solution composed of 18% PEG 4000, 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, 15% glycerol, 100 mm sodium chloride, and 1 mm redox mediator. The mediators used were methylene blue, flavin mononucleotide, and methyl viologen with midpoint potentials (Em) of +11, −238, and −488 mV, respectively, versus standard hydrogen electrode (24). The mediator solutions were degassed and placed in an electrochemical cell with a built-in graphite working electrode (2.8-cm2 surface area), a mesh platinum counter electrode separated by a Vycor conductive glass plug, and a saturated calomel electrode reference electrode (Fig. 2). The solutions were kept under a constant stream of humidified argon to maintain anaerobicity without modifying solution volume. The electrode solutions were poised at +11, −238, and −488 mV versus normal hydrogen electrode for methylene blue, flavin mononucleotide, and methyl viologen, respectively. An OMNI-101 microprocessor-controlled potentiostat (Cypress Systems, Lawrence, KS) was used to control potential, and constant stirring was used to achieve a uniform solution. The submerged sandwich looped crystals were allowed to soak for 1 h and immediately flash cooled in liquid nitrogen to preserve the poised states.

Data collection and refinement

Data were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource BL12-2 for native A. vinelandii MoFe protein poised at three defined potentials. Due to the increased susceptibility to radiation damage caused by the mediator solution treatment, only partial data sets could be collected. Processed data completeness (∼60%) and resolution (∼2.2 Å) were similar for the poised data sets (Table 1 and Tables S1 and S2) (25). The previously determined MoFe protein structure P2+ state (Protein Data Bank code 2MIN) was used as an initial model for refinement (26–29). The P1+ structure has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as entry 6CDK. Feature-enhanced electron density map (FEM) was calculated using phenix.fem (16). Difference electron density maps were calculated using Phenix (26) and CCP4 (29) program suites.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for P1+ data set

CC, correlation coefficient; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

| P1+ data set | |

|---|---|

| Data statistics | |

| Cell dimensions | a = 80.79 Å, b = 130.78 Å, c = 107.88 Å, α = γ = 90.00°, β = 110.85 |

| Space group | P21 |

| Wavelength | λ1 = 0.97947 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.10 |

| Completeness (%) | 57.06 (60.8)a |

| Observed reflections | 150,869 |

| Unique reflections | 70,560 |

| Average redundancy | 2.1 |

| I/σ | 4.0 (1.3)a |

| Rsym (%) | 14.2 (54.4)a |

| CC (1/2) | 0.992 (0.814)a |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.1 |

| Rcryst (%) | 23.2 |

| Rfree (%) | 26.3 |

| Real-space CC (%) | |

| Mean B value (overall; Å) | 24.5 |

| Coordinate error (based on maximum likelihood; Å) | 0.22 |

| r.m.s.d. from ideality | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.018 |

| Angles (°) | 2.291 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored (%) | 95.08 |

| Additional allowed (%) | 4.67 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.25 |

a Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest-resolution shell.

Computational methods

Electronic structure calculations of the structure and energetics of different states of the P-cluster were performed based on broken-symmetry DFT. The DFT model includes the P-cluster, all residues covalently bonded to the cluster, all residues with protic hydrogens within hydrogen-bonding distance of the P-cluster, and all waters within hydrogen-bonding distance of any of the above. Residues were truncated at the β-carbon and hydrogen-terminated unless the backbone participated in any included hydrogen-bonding interactions. When backbones were retained, the backbones were methyl-terminated beyond the included residues. The quantum mechanics structure was taken from a representative configuration of the enzyme generated as obtained from molecular dynamics simulations of the nitrogenase complex. Details about the molecular dynamics simulation and electronic structure methods are included as supporting information. The structures were optimized in the gas phase, keeping the position of the carbon atoms of the residues that were truncated frozen (Fig. S1). Calculations were performed with the NWChem (30) 6.6 quantum chemistry package using both the BP86 exchange and correlation functional (31, 32) and, for select structures, the B3LYP hybrid functional (33). The calculations adopted the following basis sets: Ahlrichs and co-workers (34) VTZ (valence triple zeta) for iron, 6–311++G** (35, 36) for the atoms coordinated to the iron atoms or belonging to moieties engaging direct hydrogen bonds with the P cluster, and 6–31G* (37) for all other atoms (Fig. S1). The effect of the protein environment beyond the outer coordination sphere of the P-cluster explicitly included in the calculation was modeled as a dielectric continuum using the conductor-like screening model (COSMO) framework using a dielectric constant of 10 (38, 39). Due to numerical instabilities in the vibrational analysis for some states, we were only able to obtain reliable zero-point correction for eight of the considered 12 states using normal mode analysis performed within the rigid rotor-harmonic approximation after projecting out spurious imaginary frequencies arising from the positional constraints in the geometries. For this reason, we used an approximation where we correct for the energy of the vibrational mode associated with the lost –OH (41.5 kJ/mol) or –NH bond (40.5 kJ/mol). We benchmarked this approximation against the calculated full zero-point correction energy for the states for which reliable frequencies were available and found it to provide excellent results (Table S4 and Fig. S2). Absolute values for the gas-phase and solvent-phase energies as well as zero-point corrections are provided in Table S4. The relative ordering of states was also conserved if geometries were optimized using the B3LYP hybrid functional (Table S5). In the following, we discuss the BP86 energies only because this functional yields geometries for PN and P2+SC states that are in far better agreement with the crystallographic data than those produced using the B3LYP hybrid functional as reported in Table S5.

Calculations were performed on all three oxidation states of the P-cluster (PN, P2+, and P1+) with and without the Ser –OH and Cys backbone bound. For the reduced state, PN, Mössbauer studies (9) have shown that all iron atoms are in the +2 state, antiferromagnetically coupled for an overall S = 0 spin. The present calculations reproduce this experimental observation, predicting the S = 0 as the most stable (Table S3). As for the P1+ state, our calculation clearly indicates that it is a doublet (S = 1/2), whereas the P2+ state is a singlet. More details about the stability of the different oxidation states are provided in Table S7.

Ligation of Ser and Cys backbone requires their deprotonation, which implies the knowledge of the pKa values of these residues and in turn the free energy of the solvated proton in water. High-accuracy extrapolations of the latter are available (40), but their use is problematic because of inconsistencies between the level of theory adopted in the present calculations and those adopted for the extrapolation. Therefore, we avoided the direct use of the free energy of the solvated proton by estimating the overall energetics of ligation for each oxidation state of the P-cluster with respect to methanol (Ser ligation) and methylacetamide (Cys backbone amide) in aqueous solution of which accurate pKa values are available. Details of the calculation are provided in the supporting information.

Author contributions

S. M. K., O. A. Z., L. E. J., B. G., A. J. R., K. D., G. A. P., A. X. L., and S. R. data curation; S. M. K., O. A. Z., L. E. J., B. G., A. J. R., G. A. P., and A. X. L. investigation; S. M. K., O. A. Z., and K. D. writing-original draft; O. A. Z., L. C. S., and J. W. P. conceptualization; O. A. Z., L. E. J., A. J. R., K. D., B. J. E., G. A. P., and A. X. L. formal analysis; O. A. Z., S. R., L. C. S., and J. W. P. supervision; O. A. Z. validation; O. A. Z. and B. G. visualization; O. A. Z., L. E. J., B. G., K. D., G. A. P., A. X. L., L. C. S., and J. W. P. methodology; O. A. Z., L. E. J., B. G., S. R., L. C. S., and J. W. P. writing-review and editing; L. E. J., B. G., B. J. E., and S. R. software; S. R., L. C. S., and J. W. P. funding acquisition; S. R., L. C. S., and J. W. P. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the United States Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under Contract DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including Grant P41GM103393). Computer resources were provided by the W. R. Wiley Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and sponsored by DOE's Office of Biological and Environmental Research.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-1330807 (to J. W. P. and L. C. S.) and by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 (to L. E. J., B. G., and S. R.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1 and S2, Tables S1–S7, and other supporting information.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 6CDK) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- Fe protein

- iron protein

- P-cluster

- [8Fe-7S] cluster of MoFe protein

- MoFe protein

- molybdenum–iron protein

- FeMo-co

- [7Fe-9S-C-Mo-homocitrate] iron–molybdenum cofactor

- PCET

- proton-coupled electron transfer

- BP86

- Becke exchange and Perdew correlation functional

- B3LYP hybrid functional

- Becke Lee Yang Parr hybrid functional

- DFT

- density functional theory

- FEM

- feature-enhanced electron density map.

References

- 1. Burgess B. K., and Lowe D. J. (1996) Mechanism of molybdenum nitrogenase. Chem. Rev. 96, 2983–3012 10.1021/cr950055x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howard J. B., and Rees D. C. (1994) Nitrogenase: a nucleotide-dependent molecular switch. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 235–264 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hageman R. V., and Burris R. H. (1978) Nitrogenase and nitrogenase reductase associate and dissociate with each catalytic cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75, 2699–2702 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan J. M., Christiansen J., Dean D. R., and Seefeldt L. C. (1999) Spectroscopic evidence for changes in the redox state of the nitrogenase P-cluster during turnover. Biochemistry 38, 5779–5785 10.1021/bi982866b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Danyal K., Dean D. R., Hoffman B. M., and Seefeldt L. C. (2011) Electron transfer within nitrogenase: evidence for a deficit-spending mechanism. Biochemistry 50, 9255–9263 10.1021/bi201003a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tezcan F. A., Kaiser J. T., Mustafi D., Walton M. Y., Howard J. B., and Rees D. C. (2005) Nitrogenase complexes: multiple docking sites for a nucleotide switch protein. Science 309, 1377–1380 10.1126/science.1115653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lowe D. J., Fisher K., and Thorneley R. N. (1993) Klebsiella pneumoniae nitrogenase: pre-steady-state absorbance changes show that redox changes occur in the MoFe protein that depend on substrate and component protein ratio; a role for P-centres in reducing dinitrogen? Biochem. J. 292, 93–98 10.1042/bj2920093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoo S. J., Angove H. C., Papaefthymiou V., Burgess B. K., and Münck E. (2000) Mössbauer study of the MoFe protein of nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii using selective 57Fe enrichment of the M-centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 4926–4936 10.1021/ja000254k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lindahl P. A., Papaefthymiou V., Orme-Johnson W. H., and Münck E. (1988) Mössbauer studies of solid thionin-oxidized MoFe protein of nitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 19412–19418 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rupnik K., Hu Y., Lee C. C., Wiig J. A., Ribbe M. W., and Hales B. J. (2012) P+ state of nitrogenase p-cluster exhibits electronic structure of a [Fe4S4]+ cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 13749–13754 10.1021/ja304077h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peters J. W., Stowell M. H., Soltis S. M., Finnegan M. G., Johnson M. K., and Rees D. C. (1997) Redox-dependent structural changes in the nitrogenase P-cluster. Biochemistry 36, 1181–1187 10.1021/bi9626665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan M. K., Kim J., and Rees D. (1993) The nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor and P-cluster pair: 2.2 Å resolution structures. Science 260, 792–794 10.1126/science.8484118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tittsworth R. C., and Hales B. J. (1993) Detection of EPR signals assigned to the 1-equiv-oxidized P-clusters of the nitrogenase MoFe-protein from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 9763–9767 10.1021/ja00074a050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lowery T. J., Wilson P. E., Zhang B., Bunker J., Harrison R. G., Nyborg A. C., Thiriot D., and Watt G. D. (2006) Flavodoxin hydroquinone reduces Azotobacter vinelandii Fe protein to the all-ferrous redox state with a S = 0 spin state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17131–17136 10.1073/pnas.0603223103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seefeldt L. C., Hoffman B. M., and Dean D. R. (2009) Mechanism of Mo-dependent nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 701–722 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Afonine P. V., Moriarty N. W., Mustyakimov M., Sobolev O. V., Terwilliger T. C., Turk D., Urzhumtsev A., and Adams P. D. (2015) FEM: feature-enhanced map. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 71, 646–666 10.1107/S1399004714028132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lanzilotta W. N., Christiansen J., Dean D. R., and Seefeldt L. C. (1998) Evidence for coupled electron and proton transfer in the [8Fe-7S] cluster of nitrogenase. Biochemistry 37, 11376–11384 10.1021/bi980048d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Danyal K., Inglet B. S., Vincent K. A., Barney B. M., Hoffman B. M., Armstrong F. A., Dean D. R., and Seefeldt L. C. (2010) Uncoupling nitrogenase: catalytic reduction of hydrazine to ammonia by a MoFe protein in the absence of Fe protein-ATP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 13197–13199 10.1021/ja1067178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Danyal K., Rasmussen A. J., Keable S. M., Inglet B. S., Shaw S., Zadvornyy O. A., Duval S., Dean D. R., Raugei S., Peters J. W., and Seefeldt L. C. (2015) Fe protein-independent substrate reduction by nitrogenase MoFe protein variants. Biochemistry 54, 2456–2462 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duval S., Danyal K., Shaw S., Lytle A. K., Dean D. R., Hoffman B. M., Antony E., and Seefeldt L. C. (2013) Electron transfer precedes ATP hydrolysis during nitrogenase catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 16414–16419 10.1073/pnas.1311218110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang Z. Y., Danyal K., and Seefeldt L. C. (2011) Mechanism of Mo-dependent nitrogenase. Methods Mol. Biol. 766, 9–29 10.1007/978-1-61779-194-9_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burgess B. K., Jacobs D. B., and Stiefel E. I. (1980) Large-scale purification of high activity Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 614, 196–209 10.1016/0005-2744(80)90180-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sarma R., Barney B. M., Keable S., Dean D. R., Seefeldt L. C., and Peters J. W. (2010) Insights into substrate binding at FeMo-cofactor in nitrogenase from the structure of an α-70Ile MoFe protein variant. J. Inorg. Biochem. 104, 385–389 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lanzilotta W. N., and Seefeldt L. C. (1997) Changes in the midpoint potentials of the nitrogenase metal centers as a result of iron protein-molybdenum-iron protein complex formation. Biochemistry 36, 12976–12983 10.1021/bi9715371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Otwinowski Z., and Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., et al. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 10.1107/S0907444909052925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Moriarty N. W., Mustyakimov M., Terwilliger T. C., Urzhumtsev A., Zwart P. H., and Adams P. D. (2012) Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 352–367 10.1107/S0907444912001308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., and Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 10.1107/S0907444996012255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., et al. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 10.1107/S0907444910045749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valiev M., Bylaska E. J., Govind N., Kowalski K., Straatsma T. P., Van Dam H. J. J., Wang D., Nieplocha J., Apra E., Windus T. L., and de Jong W. A. (2010) NWChem: a comprehensive and scalable open-source solution for large scale molecular simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 181, 1477–1489 10.1016/j.cpc.2010.04.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perdew J. P. (1986) Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 33, 8822–8824 10.1103/PhysRevB.33.8822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Becke A. D. (1988) Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stephens P. J., Devlin F. J., Chabalowski C. F., and Frisch M. J. (1994) Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11623–11627 10.1021/j100096a001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schäfer A., Huber C., and Ahlrichs R. (1994) Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets of triple zeta valence quality for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 100, 5829–5835 10.1063/1.467146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krishnan R., Binkley J. S., Seeger R., and Pople J. A. (1980) Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 650–654 10.1063/1.438955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clark T., Chandrasekhar J., Spitznagel G. W., and Von Ragué Schleyer P. (1983) Efficient diffuse function-augmented basis sets for anion calculations. III. The 3–21+G basis set for first-row elements, Li-F. J. Comput. Chem. 4, 294–301 10.1002/jcc.540040303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hehre W. J., Ditchfield R., and Pople J. A. (1972) Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of Gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecular orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 56, 2257–2261 10.1063/1.1677527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pitera J. W., Falta M., and van Gunsteren W. F. (2001) Dielectric properties of proteins from simulation: the effects of solvent, ligands, pH, and temperature. Biophys. J. 80, 2546–2555 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76226-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li L., Li C., Zhang Z., and Alexov E. (2013) On the dielectric “constant” of proteins: smooth dielectric function for macromolecular modeling and its implementation in DelPhi. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 2126–2136 10.1021/ct400065j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kelly C. P., Cramer C. J., and Truhlar D. G. (2006) Aqueous solvation free energies of ions and ion-water clusters based on an accurate value for the absolute aqueous solvation free energy of the proton. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 16066–16081 10.1021/jp063552y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.