Abstract

Background

In growing elderly populations, there is a heavy burden of comorbidity and a high rate of geriatric syndromes (GS) including chronic pain.

Purpose

To assess the prevalence of chronic pain among individuals aged ≥65 years in the Southern District of Israel and to evaluate associations between chronic pain and other GS.

Methods

A telephone interview was conducted on a sample of older adults who live in the community. The interview included the Brief Pain Inventory and a questionnaire on common geriatric problems.

Results

Of 419 elderly individuals who agreed to be interviewed 232 (55.2%) suffered from chronic pain. Of those who reported chronic pain, 136 participants (68.6%) noted that they had very severe or unbearable pain. There were statistically significant associations between the pain itself and decline in patient’s functional status, increased falls, reduced mood, and cognitive decline.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that chronic pain is very common in older adults and that it is associated with other GS. There is a need to increase awareness of chronic pain in older adults and to emphasize the important role that it plays in their care.

Keywords: pain, impact of pain, older adults, geriatric syndromes, community dwelling

Introduction

GS1,2 are clinical conditions in older adults that do not fit into discrete disease categories.3 Conditions such as delirium, pressure ulcers, falls, and incontinence are “widely known”,3,4 but other conditions, such as visual and hearing problems, elder abuse, malnutrition, sleep problems, and even dizziness and syncope too have been included under the heading of GS.5

Pain is a very common problem among adults. The prevalence of chronic pain in the adult population ranges from 20% to 50%, depending on the study population, the sampling method, the interview method, the definition of “chronicity” and the definition of the site of pain.6–10

Many studies have investigated associations between pain and specific GS, such as functional limitations,6,7,9,11–15 affective disorders,6,10,14,16–26 cognitive decline,27–30 and falls.12 However, a literature review on the association between pain and GS and their mutual effect on outcomes, such as mortality, functional decline, falls, etc., did not yield a clear-cut picture. Lohman et al31 found that the inclusion of persistent pain as an additional criterion for frailty led to a potentially better prediction of incident adverse outcomes. Andrews et al32 looked at the cross-sectional relationship between pain and basic functional limitations and their effect on ADL disability after a 10-year follow-up. They found that pain itself is not an independent risk factor. They linked this finding to the possibility that pain and functional limitation, such as other GS, have common underlying risk factors and mechanisms. In one of the important studies that investigated the prevalence and co-occurrence of GS among community-dwelling people aged ≥75 years, the authors cited the fact that they did not assess the co-occurrence of pain GS as one of the study limitations.33 It should be noted that many of the studies that looked at the effect of GS on negative outcomes did not take pain into account.34–36

In the present study, we assessed associations between chronic pain and GS among individuals aged ≥65 years. We hypothesized that GS are very common in our study population of older individuals with chronic pain.

Methods

Study population

This was a cross-sectional telephone survey of Hebrew-speaking men and women aged ≥65 years living in the community in Beer-Sheba and its surrounding area who were insured by the Clalit Healthcare Services. The Clalit Healthcare Service is the largest health care service in Israel and insures over two-thirds of the Israeli population.

Study design and sampling process

We conducted a random sampling from a roster of 1103 patients in clinics in the Jewish sector, ≥65 years, drawn from the Clalit Healthcare Services systematic databases. As part of their training course, nursing students from the Recanati School for Community Health Professions of the Faculty of Health Sciences of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev have a research seminar on the subject of pain in older adults. They also have three communication courses on how to interview patients through different media including by telephone and then have to pass a simulated test. Before the study interviews were conducted, the 51 students, who took part in the research seminar, underwent training by one of the investigators (TF) on how to conduct the study interview by telephone, how to address the participants, and how to fill in the questionnaire.

Each completed questionnaire was examined by two of the investigators (AK and OL) and those that were not completed correctly were not used in the study.

Interviewers contacted these patients and asked them to consent to participate in the study. Those who met the study criteria and agreed verbally to participate underwent a comprehensive telephone interview. At the beginning of the interview the patients were asked whether they had suffered from persistent or intermittent pain over the previous three months? Only those patients who answered this question in the affirmative underwent a full interview with the study questionnaire.

Patients who refused to participate, who did not speak Hebrew, who were not able to participate due to hearing or comprehension impairment, who resided in old age settings, who were hospitalized, or who were away from Israel were excluded from the study.

Study instruments

The patients underwent a structured personal telephone interview. The questionnaire included questions on chronic diseases including chronic pain, sociodemographic data, and the following formal questionnaires:

To measure pain intensity, we used a five-point verbal descriptor scale, which has been shown to have low error rates and good face convergent and criterion validity.37 Patients were asked to grade their pain in terms of the following response options: no pain, slight pain, moderate pain, severe pain, and unbearable pain.

A 10-point verbal numeric scale, which was found to have high correlation with a 10-point visual analog scale,38 has also been used to measure pain intensity. Patients were asked to grade their average pain during the previous 3 months on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (unbearable pain).

The BPI39 has been used to measure pain interference. We extracted questions from this questionnaire related to the site of pain and its effect on the patient’s daily activity: overall activity, mood, walking capacity, amount and quality of sleep at night, relationships with others, need for bedrest, and routine work. The questionnaire was translated to and validated in Hebrew from previous research.40

A GS questionnaire including dichotomous questions (yes/no) on BADL (“Do you dress alone?”, “Do you wash alone?”), IADL (“Do you shop on your own?”, “Do you prepare your own meals?”), questions on falls (“Did you fall over the previous year? If yes, how many times?”), a question on weight loss (“Did you have an unplanned loss of weight of 5 kg or more over the last six months?”), a question on cognitive status (“Do you have memory problems?”), a question on mood (“Have you mostly felt depressed or sad over the last two months?”), and a question on polypharmacy (“Do you take six or more drugs on a regular basis?”). These questions were taken from a computerized screening questionnaire that is routinely filled in by nurses in the Clalit Healthcare Services clinics while screening patients with geriatric problems.41

Sample size calculation

The Southern District has 52,000 patients aged 65 years or above. Assuming that 25% suffer from chronic pain,6 the required sample size to assess the rate of patients with chronic pain with an accuracy of 10% would be 75 patients. It also has 27,000 elderly patients aged 75 years or above. Assuming that 50% of these have chronic pain,10 the required sample size to assess the rate of chronic pain with accuracy of 10% would be 96 patients. To cover both of these conditions with accuracy of 10% and under the assumption that we would need 96 patients 75 years or above and that this group represents about 50% of the patients aged ≥65 years (27000/52000), we would need 210 patients. To compensate for potential mistakes and missing values, the final sample size was 232 patients.

Statistical analyses

A descriptive analysis was performed with means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. The association between severity of pain and its effect on daily living with the presence of various GS was tested by Student’s t-test. The association between the number of GS and the severity of pain and its effect on daily living were analyzed by analysis of variance. Logistic regression models were used to find associations among chronic pain and GS. Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05.

The study was approved by the Helsinki Committee of the Meir Medical Center (approval #095/2014k).

Results

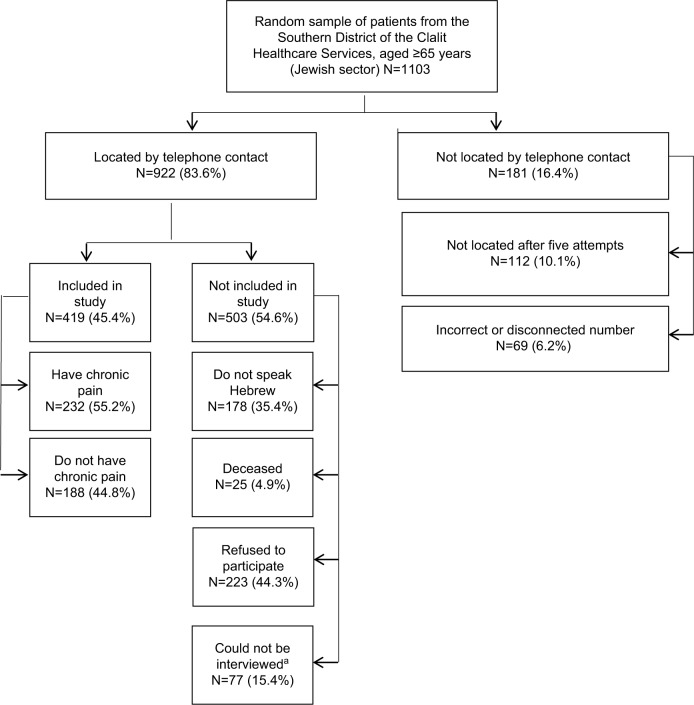

Nine hundred and twenty-two patients, of the original random sample of 1103 individuals insured by the Clalit Healthcare Services, were located for an interview. Of these, 223 refused to be interviewed, 255 were not capable of being interviewed (77 due to hearing or other communication problems and the other 178 because they did not speak Hebrew), and 25 died before telephone contact with them. In all, 420 patients could be interviewed and consented to participate. Of these, 188 (44.8%) reported that they did not suffer from chronic pain, so the interview with them was discontinued. Chronic pain over the previous 3 months at least was reported by 232 patients (55.2%), and they underwent the full interview (Figure 1). The mean age was 73.7 ± 6.5 years and 89 (38.4%) were men. The sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of study patients

Note: aCould not be interviewed: do not hear, do not communicate, nursing home, hospitalized, abroad, other problems.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study population (N = 232)

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 89 | 38.4 |

| Female | 142 | 61.2 |

| Total | 231 | (mis = 1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 73.7 ± 6.5 | |

| Range | 65–101 | |

| Total | 232 | |

| Place of birth | ||

| Israel | 19 | 8.2 |

| Asia/North Africa | 123 | 53.0 |

| Eastern Europe/former USSR | 69 | 29.7 |

| Western Europe/North and South America | 19 | 8.2 |

| Total | 230 | (mis = 2) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 0 | 0.0 |

| Married | 142 | 61.2 |

| Divorced | 14 | 6.0 |

| Widowed | 74 | 31.9 |

| Separated | 2 | 0.9 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Education (years) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 10.95 ± 4.29 | |

| Range | 0–25 | |

| Total | 211 | (mis = 11) |

| Employment | ||

| Salaried | 10 | 4.3 |

| Partially salaried | 3 | 1.3 |

| Self-employed | 10 | 4.3 |

| Retired | 184 | 79.3 |

| Housewife | 12 | 5.2 |

| Unemployed | 6 | 2.6 |

| Total | 225 | (mis = 7) |

| Religious identity | ||

| Agnostic | 72 | 31.0 |

| Religious | 37 | 15.9 |

| Traditional | 123 | 53.0 |

| Total | 232 |

Abbreviation: mis, missing data regarding some participants.

The characteristics of the pain and its effects

One hundred eighty-two (78.4%) reported a single pain site, 40 (17.2%) reported two sites, and 10 (4.4%) reported three or more sites. The three most common pain sites were the back (37.5%), the knee (26.7%), and the limbs (22.8%).

Based on the five-point verbal descriptor scale, 136 of 232 (58.6%) graded their pain as severe or unbearable. The mean pain severity on the 10-point numeric rating scale was 7.1 ± 2.1. Based on the BPI measure of the effect of pain on overall activity (pain interference), the mean score was 4.9 ± 2.4 on the scale from 0 to 10 (Table 2). Only 41.4% of the patients with chronic pain were treated with analgesics.

Table 2.

Pain characteristics and impact (N = 232)

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of pain sites | ||

| 1 | 182 | 78.4 |

| 2 | 40 | 17.2 |

| 3 | 8 | 3.4 |

| 4+ | 2 | 0.9 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Pain site (more than one is possible) | ||

| Back | 87 | 37.5 |

| Knee | 62 | 26.7 |

| Limbs | 53 | 22.8 |

| Shoulder | 32 | 13.8 |

| Head | 21 | 9.1 |

| Other | 21 | 9.1 |

| Chest | 10 | 4.3 |

| Abdomen | 9 | 3.9 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Pain level—five-point verbal descriptor scale | ||

| No pain | 0 | 0 |

| Mild pain | 14 | 6.0 |

| Moderate pain | 82 | 35.3 |

| Severe pain | 95 | 40.9 |

| Unbearable pain | 41 | 17.7 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Pain intensity—10-point verbal numeric rating | ||

| Scale (0 = no pain,10 = unbearable pain) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 7.1 ± 2.1 | |

| Range | 1–10 | |

| Total | 230 | (mis = 2) |

| Impact of pain on daily activity (0 = no impact, 10 = very high impact) | ||

| General activity | 5.7 ± 2.9 | |

| Mood | 5.1 ± 3.4 | |

| Ambulation | 5.3 ± 3.1 | |

| Work | 4.8 ± 3.3 | |

| Relationships | 2.7 ± 3.1 | |

| Sleep | 5.3 ± 3.4 | |

| Pleasure | 5.3 ± 3.3 | |

| Pain interference | ||

| Mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 2.4 | |

| Range | 0–10 | |

| Total | 223 | (mis = 9) |

Abbreviation: mis, missing data regarding some participants.

The prevalence of GS

The data on the prevalence of GS is presented in Table 3. One hundred ninety-eight (85.4%) reported any type of GS. The most common problem was dependency at grocery shopping, with 51.7% reporting this as a problem. The least common problem was dependency at dressing as only 15.5% of the participants were not capable of dressing themselves.

Table 3.

Rate of geriatric syndromes (N=232)

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent with grocery shopping | ||

| Yes | 112 | 48.3 |

| No | 120 | 51.7 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Independent with preparing meals | ||

| Yes | 133 | 57.3 |

| No | 99 | 42.7 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Independent with bathing | ||

| Yes | 185 | 79.7 |

| No | 47 | 20.3 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Independent with dressing | ||

| Yes | 196 | 84.5 |

| No | 36 | 15.5 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Any dependency in ADLb | ||

| Yes | 200 | 86.2 |

| No | 32 | 13.8 |

| Total | 232 | |

| Falls in the past year | ||

| Yes | 84 | 36.8 |

| No | 144 | 63.2 |

| Total | 228 | (mis = 4) |

| If yes, number of falls | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 1.8 | |

| Range | 1–10 | |

| Total | 79 | (mis = 5) |

| Unplanned loss of weight of 5 kg or more over the last 6 months | ||

| Yes | 35 | 15.8 |

| No | 186 | 84.2 |

| Total | 221 | (mis = 11) |

| Memory loss | ||

| Yes | 103 | 45.4 |

| No | 124 | 54.6 |

| Total | 227 | (mis = 5) |

| Depressed or sad in the past 2 months | ||

| Yes | 97 | 43.1 |

| No | 128 | 56.9 |

| Total | 225 | (mis = 7) |

| Six or more regular medications | ||

| Yes | 104 | 45.8 |

| No | 123 | 54.2 |

| Total | 227 | (mis = 5) |

| Geriatric syndromesb | ||

| 0 | 34 | 14.7 |

| 1–2 | 90 | 38.8 |

| 3–6 | 108 | 46.6 |

| Total | 232 |

Notes:

Any dependence on ADL—if the answer to one of the ADL questions (dressing, washing, shopping, or preparing food) was positive.

If the answer to one of the ADL questions was positive, ADL was considered to be impaired and none of the other questions in this category were taken into account for the calculation of the number of geriatric syndromes.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; mis, missing data regarding some participants.

Table 4 shows the association between the presence of a GS and the severity of pain and its effect on overall activity. There was no statistically significant association between the severity of pain and falls over the previous year. A statistically significant association was found with the severity of pain and its effect on overall activity for all the other GS.

Table 4.

Association between the number of geriatric syndromes, the intensity of pain, and the effect of pain on overall activity

| N | Pain intensitya

|

Pain interferenceb

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n | P | Mean | SD | n | P | ||

| Any dependency in ADLc | |||||||||

| Yes | 145 | 7.4 | 2.1 | 144 | 0.004 | 5.7 | 2.2 | 139 | <0.0001 |

| No | 87 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 86 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 84 | ||

| Falls over the previous year | |||||||||

| Yes | 84 | 7.4 | 2.1 | 83 | 0.051 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 81 | <0.0001 |

| No | 144 | 6.9 | 2.2 | 143 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 139 | ||

| Unplanned loss of weight of 5 kg or more over the last 6 months | |||||||||

| Yes | 35 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 34 | 0.016 | 5.7 | 2.3 | 33 | 0.014 |

| No | 186 | 6.9 | 2.1 | 185 | 4.6 | 2.4 | 180 | ||

| Memory loss | |||||||||

| Yes | 103 | 7.5 | 2.1 | 101 | 0.009 | 5.5 | 2.4 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| No | 124 | 6.7 | 2.2 | 124 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 119 | ||

| Depressed or sad in the past 2 months | |||||||||

| Yes | 97 | 7.5 | 2.1 | 95 | 0.005 | 6.2 | 2.1 | 91 | <0.0001 |

| No | 128 | 6.7 | 2.1 | 128 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 126 | ||

| Six or more regular medications | |||||||||

| Yes | 104 | 7.6 | 1.9 | 103 | 0.001 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 101 | <0.0001 |

| No | 123 | 6.7 | 2.2 | 122 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 118 | ||

| Number of geriatric syndromes | |||||||||

| 0 | 34 | 6.3 | 2.4 | 34 | <0.0001 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 33 | <0.0001 |

| 1–2 | 90 | 6.7 | 2.1 | 90 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 85 | ||

| 3–6 | 108 | 7.7 | 1.9 | 106 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 105 | ||

Notes:

10-point verbal numeric scale (0 = no pain, 10 = unbearable pain);

Effect of pain on overall activity (0 = usual activity, 10 = no activity);

Unable to perform at least one of the following activities independently: dressing, washing, preparing a meal, shopping.

Abbreviation: ADL, activities of daily living.

The severity of pain ranged from a mean of 6.3 ± 2.4 among participants without GS to 6.7 ± 2.1 for those with 1–2 GS and 7.7 ± 1.9 for those with three or more GS (P < 0.0001). Similarly, the mean score for the effect of pain on overall activity (pain interference) ranged from 3.1 ± 2.1 for participants without GS to 6.2 ± 1.9 among those with three or more GS (P < 0.0001).

To check the effect of pain on the spectrum of GS, we built logistic regression models with the following dependent variables: functional state (any dependency in IADL, any dependency in BADL, and any dependency in ADL), depressive mood, and memory loss (Table 5). The only variable that predicted pain intensity was any dependency in BADL (odds ratio = 1.41, 95% confidence interval: 1.15–1.71, P = 0.001).

Table 5.

Relationship between pain level and GS (IADL, BADL, any dependency in ADL, depression, and memory problems) by logistic regression analysis

| Model | Variable | OR | 95% CI

|

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Any dependency in IADLa | Age | 1.138 | 1.076 | 1.203 | 0.000 |

| Gender (male) | 1.330 | 0.683 | 2.589 | 0.402 | |

| Memory problems | 1.386 | 0.712 | 2.699 | 0.337 | |

| Depression | 5.028 | 2.466 | 10.252 | 0.000 | |

| Pain level (0–10) | 1.129 | 0.967 | 1.317 | 0.124 | |

|

| |||||

| Any dependency in BADLb | Age | 1.099 | 1.041 | 1.160 | 0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 0.609 | 0.284 | 1.307 | 0.203 | |

| Memory problems | 0.737 | 0.343 | 1.584 | 0.434 | |

| Depression | 6.330 | 2.924 | 13.700 | 0.000 | |

| Pain level (0–10) | 1.405 | 1.154 | 1.711 | 0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Any dependency in ADLc | Age | 1.139 | 1.076 | 1.205 | 0.000 |

| Gender (male) | 1.421 | 0.721 | 2.802 | 0.310 | |

| Memory problems | 1.349 | 0.684 | 2.660 | 0.388 | |

| Depression | 6.024 | 2.877 | 12.611 | 0.000 | |

| Pain level (0–10) | 1.157 | 0.989 | 1.353 | 0.069 | |

|

| |||||

| Depressed or sad in the past 2 months | Age | 1.007 | 0.960 | 1.057 | 0.771 |

| Gender (male) | 0.620 | 0.324 | 1.189 | 0.150 | |

| Memory problems | 3.253 | 1.752 | 6.041 | 0.000 | |

| Depression | 5.969 | 2.863 | 12.447 | 0.000 | |

| Pain level (0–10) | 1.076 | 0.924 | 1.253 | 0.346 | |

|

| |||||

| Memory loss | Age | 0.992 | 0.948 | 1.039 | 0.742 |

| Gender (male) | 0.770 | 0.423 | 1.402 | 0.393 | |

| Memory problems | 3.248 | 1.749 | 6.031 | 0.000 | |

| Depression | 1.396 | 0.708 | 2.755 | 0.336 | |

| Pain level (0–10) | 1.114 | 0.968 | 1.281 | 0.132 | |

Notes:

Any dependency in IADL—if the answer to one of the IADL (instrumental activities of daily living) questions (shopping or preparing food) was positive.

Any dependency in BADL—if the answer to one of the BADL questions (dressing, washing, shopping, or preparing food) was positive.

Any dependency in ADL—if the answer to one of the ADL questions (dressing, washing, shopping, or preparing food) was positive.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; BADL, basic activities of daily living; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CI, confidence interval; GS, geriatric syndromes; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; OR, odds ratio

Discussion

In a telephone survey of patients ≥65 years living in the community, we found that more than half of the participants reported pain that lasted for at least 3 months. We also found that the severity of chronic pain and its interference with overall activity were of significance in a large number of patients with GS (Table 4). The prevalence of pain in our results is similar to those of Raftery et al10 who reported that about 50% of patients in the ≥65 years age group living in the community reported pain for 3 or more months. Our results are higher than those of other studies.6,8,9,42 These differences stem from lack of uniformity among these studies in terms of age, setting, and definition of chronic pain. Thus, for example, Pereira et al9 found a rate of 30% among elderly patients who were hospitalized for rehabilitation, while Johannes et al8 reported a rate of 38.5% among patients in this age group living in the community. In our sample, 94% of patients with chronic pain reported at least a moderate severity of pain and almost 60% complained of severe or very severe pain that had a negative effect on their daily activity. However, only 41.4% participants with chronic pain took analgesics. Similar results have been reported in the past28,43 and they may be related to problems in the diagnosis of pain44,45 on the part of both the patients and the physicians and poor patient–doctor concordance in evaluation of the pain.12 These findings are of great concern since, according to the results of a recently published study,7 direct intervention in the treatment of joint pain can, theoretically, reduce functional impairment.

The findings of the present study on the association between chronic pain and GS is supported by the results of many previous studies, which also reported associations between chronic pain and functional impairment,6,7,9,11–15 falls,12 cognitive problems,27–30 and impaired mood.6,10,14,16–26

The overlap between pain and cognition would appear to be the fact that pain has a clear cognitive element that necessitates recall of past experience and decision making,29 since these two processes (chronic pain and cognition) utilize the element of attention.46 In the review by Moriarty et al,29 the authors raised an important question as to the association between the treatment administered for chronic pain and cognitive impairment: in some cases, this treatment can cause cognitive impairment, while in others, not only does analgesic therapy not cause cognitive impairment but it might even improve it. In fact, cognitive impairment can lead to the failure of appropriate treatment for chronic pain.28

As noted, the association between chronic pain and affective changes has been investigated extensively in the past. Most of the longitudinal studies showed that the relationship between depression and chronic pain is bidirectional, where chronic pain can cause depression and depression can lead to development or exacerbation of chronic pain.18

The combination of pain and depression was found to be related to a negative health cognitive bias that makes patients more exposed to and more focused on their pain.47 Depression can lead patients to a negative and pessimistic perception of the future and can have a negative effect on the patient’s capacity to cope with pain.48 In neurobiologic terms, the main noradrenergic and serotonergic nuclei in the central nervous system are responsible for the chronicity of pain and development of depression.49,50

The finding in the present study of a high rate of chronic pain that is associated with a high prevalence of GS in the elderly population highlights the need for a comprehensive plan to actively identify elderly patients with these problems.

As noted above, the Clalit Healthcare Services has a computerized system for initial screening of the elderly for the identification of GS,41 but this system does not relate at all to the issue of pain. It should be upgraded to include this condition.

Many studies assessed associations between GS and pain, but each of these reported on only one or two GS.6,7,9–30 In contrast, studies that assessed multiple, rather than specific, GS usually did not assess the co-occurrence of pain.33,51 In the present study, we assessed the co-occurrence of chronic pain with multiple GS.

In the univariate analysis, we found a high rate of co-occurrence of pain in all the GS that were evaluated. In the logistic regression analysis, we found that chronic pain, as an independent variable, along with more advanced age and the presence of depression, predicts dependency in BADL. Although it is not possible, using a cross-sectional research design, to determine whether chronic pain predicts dependency in BADL or whether the association is bidirectional, our finding does strengthen the assumption of Andrews et al, on common underlying risk factors and mechanisms between pain and the other GS.32

Our study has some advantages. It was conducted in a population of elderly individuals living in the community who were selected at random, so it is reasonable to assume that the results can be generalized to other elderly populations.

However, it also has several limitations. First, the evaluation was conducted by telephone interview and not face to face, and the data received from the patient, such as medication or cognitive state, were not confirmed vis-a-vis data from the medical records. The large number of interviewers in this study is also a potential limitation. Even though all the students who conducted the interviews underwent intensive training, the large number of interviewers (51) made it impossible to ensure the quality of all the interviews.

In the present study we cannot rule out the possibility of systematic biases, such as selection or information bias. Because of the study design, our data were based on subjective reporting of pain without any objective assessment, so we cannot confirm that the patients included in the study actually suffered from chronic pain as they reported. Therefore, we cannot rule out information bias. The study was conducted on a random sample of patients registered in the Clalit Healthcare Services, which provides medical care for two-thirds of Israel’s aged ≥ 65 years population. This reduces the risk of selection bias but does not totally eliminate the possibility that proper randomization was not achieved.

Another significant limitation is the less than optimal planning of the study. Of the 419 patients who agreed to participate in and completed the interview, 188 (44.8%) did not report any chronic pain so they were not asked to answer questions on co-morbid conditions or GS. In addition, 223 of the 922 elderly patients (24.2%) refused to be interviewed and another 255 (27.7%) could not be interviewed because they did not speak Hebrew (N = 178) or because communication with them was impossible (N = 77), usually due to impaired hearing. We cannot rule out the possibility that the prevalence of GS among those who did not participate may have been different from those who did participate.

Furthermore, over 25% of the study participants reported cognitive decline or a depressed mood, both of which could have affected their self-assessment of chronic pain. The patients were not asked about specific drug therapy in the interview, except indirectly through the questions of poly-pharmacy and chronic co-morbidity. Clearly, medications and medical history are important information in a study on pain, but these areas were not covered in the study questionnaire out of concern that the questionnaire would become too long and difficult to complete. The absence of this important information is an additional limitation of the study.

Another weakness is that the presence of GS was determined by means of a single dichotomous question and not by a more comprehensive assessment, for example, a full functional assessment or a formal cognitive assessment. Thus, the true rate of GS in the community may be different from the data that we presented here. Furthermore, we used the standard screening questionnaire of Clalit Healthcare Services, which did not include well-recognized GS, such as delirium, pressure sores, and incontinence, making the drawing of general conclusions more problematic.

Because of the cross-sectional design of the study, we can only discuss association, not causality, between chronic pain and GS.

Conclusion

In a random study of individuals aged ≥65 years living in the community, we found a high rate of chronic pain and GS as well as an association between them. There is a need for further studies to investigate these issues in depth, using accepted geriatric instruments for the determination of GS. This will facilitate more optimal care for the elderly population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the nursing students of the Recanati School for Community Health Professions of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev for conducting the study interviews. This study was partially supported by a grant from the Recanati School for Community Health Professions, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel.

Abbreviations

- ADL

activities of daily living

- BADL

basic activities of daily living

- BPI

Brief Pain Inventory

- GS

geriatric syndromes

- IADL

instrumental activities of daily living

Footnotes

Author contributions

Orly Liberman designed the study, supervised the data collection, and wrote the article. Tamar Freud was responsible for the statistical design of the study and for carrying out the statistical analysis. Roni Peleg designed the study and assisted with writing the article. Ariela Keren supervised the data collection and assisted with writing the article. Yan Press designed the study and wrote the article. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Orly Liberman and Ariela Keren are employed at the Recanati School for Community Health Professions. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Weber P, Meluzinova H, Matejovska-Kubesova H, et al. Geriatric giants--contemporary occurrence in 12,210 in-patients. Bratisl Med J. 2015;116(7):408–416. doi: 10.4149/bll_2015_078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noguchi N, Blyth FM, Waite LM, et al. Prevalence of the geriatric syndromes and frailty in older men living in the community: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(4):255–261. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;273(17):1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senn N, Monod S. Development of a comprehensive approach for the early diagnosis of geriatric syndromes in general practice. Front Med. 2015(2):78. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hairi NN, Cumming RG, Blyth FM, Naganathan V. Chronic pain, impact of pain and pain severity with physical disability in older people–is there a gender difference? Maturitas. 2013;74(1):68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henchoz Y, Bula C, Guessous I, et al. Chronic symptoms in a representative sample of community-dwelling older people: a cross-sectional study in Switzerland. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e014485. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. Journal Pain. 2010;11(11):1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira LS, Sherrington C, Ferreira ML, et al. Self-reported chronic pain is associated with physical performance in older people leaving aged care rehabilitation. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:259–265. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S51807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raftery MN, Sarma K, Murphy AW, De la Harpe D, Normand C, McGuire BE. Chronic pain in the Republic of Ireland--community prevalence, psychosocial profile and predictors of pain-related disability: results from the Prevalence, Impact and Cost of Chronic Pain (PRIME) study, part 1. Pain. 2011;152(5):1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covinsky KE, Lindquist K, Dunlop DD, Yelin E. Pain, functional limitations, and aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1556–1561. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruschinski C, Wiese B, Dierks ML, Hummers-Pradier E, Schneider N, Junius-Walker U. A geriatric assessment in general practice: prevalence, location, impact and doctor-patient perceptions of pain. BMC Fam Prac. 2016;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0409-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scudds RJ, Ostbye T. Pain and pain-related interference with function in older Canadians: the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(15):654–664. doi: 10.1080/09638280110043942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shega JW, Tiedt AD, Grant K, Dale W. Pain measurement in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: presence, intensity, and location. 2 Suppl. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69:S191–S197. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmaciu C, Iliffe S, Kharicha K, et al. Health risk appraisal in older people 3: prevalence, impact, and context of pain and their implications for GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(541):630–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguera-Ortiz L, Failde I, Cervilla JA, Mico JA. Unexplained pain complaints and depression in older people in primary care. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(6):574–577. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biddulph JP, Iliffe S, Kharicha K, et al. Risk factors for depressed mood amongst a community dwelling older age population in England: cross-sectional survey data from the PRO-AGE study. BMC Geriatr. 2014(14):5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Wu J, Bair MJ, Krebs EE, Damush TM, Tu W. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-month longitudinal analysis in primary care. J Pain. 2011;12(9):964–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leong IY, Farrell MJ, Helme RD, Gibson SJ. The relationship between medical comorbidity and self-rated pain, mood disturbance, and function in older people with chronic pain. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(5):550–555. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerman SF, Rudich Z, Brill S, Shalev H, Shahar G. Longitudinal associations between depression, anxiety, pain, and pain-related disability in chronic pain patients. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(3):333–341. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallen CD, Peat G. Screening older people with musculoskeletal pain for depressive symptoms in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(555):688–693. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X342228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer T, Cooper J, Raspe H. Disabling low back pain and depressive symptoms in the community-dwelling elderly: a prospective study. Spine. 2007;32(21):2380–2386. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181557955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mossey JM, Gallagher RM. The longitudinal occurrence and impact of comorbid chronic pain and chronic depression over two years in continuing care retirement community residents. Pain Med. 2004;5(4):335–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parmelee PA, Harralson TL, McPherron JA, Schumacher HR. The structure of affective symptomatology in older adults with osteoarthritis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(4):393–401. doi: 10.1002/gps.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salazar A, Duenas M, Mico JA, et al. Undiagnosed mood disorders and sleep disturbances in primary care patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2013;14(9):1416–1425. doi: 10.1111/pme.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shipton E, Ponnamperuma D, Wells E, Trewin B. Demographic characteristics, psychosocial measures, and pain in a sample of patients with persistent pain referred to a new zealand tertiary pain medicine center. Pain Med. 2013;14(7):1101–1107. doi: 10.1111/pme.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karp JF, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Butters MA, et al. The relationship between pain and mental flexibility in older adult pain clinic patients. Pain Med. 2006;7(5):444–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landi F, Onder G, Cesari M, et al. Pain management in frail, community-living elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(22):2721–2724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.22.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moriarty O, McGuire BE, Finn DP. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(3):385–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner DK, Rudy TE, Morrow L, Slaboda J, Lieber S. The relationship between pain, neuropsychological performance, and physical function in community-dwelling older adults with chronic low back pain. Pain Med. 2006;7(1):60–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lohman MC, Whiteman KL, Greenberg RL, Bruce ML. Incorporating persistent pain in phenotypic frailty measurement and prediction of adverse health outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(2):216–222. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrews JS, Cenzer IS, Yelin E, Covinsky KE. Pain as a risk factor for disability or death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):583–589. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabue-Teguo M, Grasset L, Avila-Funes JA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of geriatric syndromes in people aged 75 years and older in France: results from the Bordeaux Three-city Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;73(1):109–116. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ. Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Intern Med J. 2008;38(1):16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang CC, Lee JD, Yang DC, Shih HI, Sun CY, Chang CM. Associations between geriatric syndromes and mortality in community-dwelling elderly: results of a national longitudinal study in Taiwan. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(3):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kane RL, Shamliyan T, Talley K, Pacala J. J Am Geriatr Soc. 5. Vol. 60. The association; 2012. between geriatric syndromes and survival; pp. 896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagliese L, Weizblit N, Ellis W, Chan VW. The measurement of postoperative pain: a comparison of intensity scales in younger and older surgical patients. Pain. 2005;117(3):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holdgate A, Asha S, Craig J, Thompson J. Comparison of a verbal numeric rating scale with the visual analogue scale for the measurement of acute pain. Emerg Med. 2003;15:5–6. 441–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2003.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neville A, Peleg R, Singer Y, Sherf M, Shvartzman P. Chronic pain: a population-based study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10(10):676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Press Y, Hazzan R, Clarfield A, Dwolatzky T. A semistructured computerized screening interview for the assessment of older patients in the primary care setting. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2009;3:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:2–3. 127–134. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Management of nonmalignant pain in home-dwelling older people: a population-based survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1861–1865. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gloth FM., 3rd Pain management in older adults: prevention and treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(2):188–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Von Roenn JH, Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Pandya KJ. Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management. A survey from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(2):121–126. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oosterman JM, de Vries K, Dijkerman HC, de Haan EH, Scherder EJ. Exploring the relationship between cognition and self-reported pain in residents of homes for the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(1):157–163. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rusu AC, Pincus T, Morley S. Depressed pain patients differ from other depressed groups: examination of cognitive content in a sentence completion task. Pain. 2012;153(9):1898–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Von Korff M, Simon G. The relationship between pain and depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;30:101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alba-Delgado C, Borges G, Sanchez-Blazquez P, et al. The function of alpha-2-adrenoceptors in the rat locus coeruleus is preserved in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Psychopharma-cology. 2012;221(1):53–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alba-Delgado C, Mico JA, Sanchez-Blazquez P, Berrocoso E. Analgesic antidepressants promote the responsiveness of locus coeruleus neurons to noxious stimulation: implications for neuropathic pain. Pain. 2012;153(7):1438–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lakhan P, Jones M, Wilson A, Courtney M, Hirdes J, Gray LC. A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2001–2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]