Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to describe the conceptual and implementation approach of selected digital health technologies that were tailored in various resource-constrained countries. To provide insights from a donor-funded project implementer perspective on the practical aspects based on local context and recommendations on future directions.

Methods

Drawing from our multi-year institutional experience in more than 20 high disease-burden countries that aspire to meet the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3, we screened internal project documentation on various digital health tools that provide clarity in the conceptual and implementation approach. Taking into account geographic diversity, we provide a descriptive review of five selected case studies from Bangladesh (Asia), Mali (Francophone Africa), Uganda (East Africa), Mozambique (Lusophone Africa), and Namibia (Southern Africa).

Findings

A key lesson learned is to harness and build on existing governance structures. The use of data for decision-making at all levels needs to be cultivated and sustained through multi-stakeholder partnerships. The next phase of information management development is to build systems for triangulation of data from patients, commodities, geomapping, and other parameters of the pharmaceutical system. A well-defined research agenda must be developed to determine the effectiveness of the country- and regional-level dashboards as an early warning system to mitigate stock-outs and wastage of medicines and commodities.

Conclusion

The level of engagement with users and stakeholders was resource-intensive and required an iterative process to ensure successful implementation. Ensuring user acceptance, ownership, and a culture of data use for decision-making takes time and effort to build human resource capacity. For future United Nations voluntary national reviews, countries and global stakeholders must establish appropriate measurement frameworks to enable the compilation of disaggregated data on Sustainable Development Goal 3 indicators as a precondition to fully realize the potential of digital health technologies.

Keywords: Access to medicines, decision-making, digital health, eHealth, low- and middle-income countries

Background

As part of the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 for ensuring healthy lives, access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all (target 3.8) is a fundamental component of Universal Health Coverage. Target 3.b seeks indicator-based data on the proportion of health facilities having a core set of essential medicines that are available and affordable.1 The Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines for Universal Health Coverage recommended that countries establish and maintain information systems for periodic monitoring of medicine availability, pricing, and affordability.2 Reliable information systems are crucial to support policy makers and leaders working toward the SDG 3 targets, particularly ensuring clinical quality, efficiency, and safety in Universal Health Coverage-oriented medicines benefit schemes.3 Information is essential to the seven components of the pharmaceutical system and its measurement of system performance and resilience.4

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development encourages countries to conduct voluntary national reviews to track progress toward the SDGs. Countries that participated in the 2016 voluntary national reviews showed that significant effort is needed to collect data due to a lack of disaggregated data and limited availability of relevant indicators and high-quality data.5 In Uganda, only 80 of 230 global indicators for SDGs had readily available data, and multi-year plans were made to track progress against the global indicators for future voluntary national reviews.6 Madagascar considers the private sector to be the ‘engine of development’ and seeks cooperation to establish an efficient information system that enables harmonization among all technical and financial partners.7 These challenges of a lack of disaggregated data and a need for analytics persisted among the next set of countries that conducted voluntary national reviews in July 2017.8 This underscores the urgency for digital health technologies to dynamically adapt to a country-specific context in order to help track progress for SDG 3 targets. Digital health technologies must take into account information needs that are people-centered and usable for a country’s next cycle of voluntary national reviews while also informing the periodic global dialogue.

The first objective of the study was to describe the conceptual and implementation approach of selected digital health technologies in various resource-constrained countries. The paper provides insights from a donor-funded project implementer perspective on the practical aspects based on local context and recommendations on future directions. Based on a synthesis of lessons learned from our multi-country partnerships with Ministry of Health programs and other relevant stakeholders, the second objective of our paper was to describe how our work will set the stage for advocacy, policy, and future research on digital health technologies. Our paper ends with a discussion on what needs to be done to enable the use of digital health technologies to measure the achievement of the targets within SDG 3.

Methods: Approach for digital health technologies to support access to medicines and pharmaceutical services

Historically, our projects have advocated for, designed, and implemented a pharmaceutical management information system that builds on a country’s existing forms, reports, and procedures as much as possible, taking into account health worker context. The conceptual and practical approach to pharmaceutical management information systems is extensively documented elsewhere.9 An efficient pharmaceutical management information system requires policy makers, program managers, and health care providers to monitor information related to the availability of medicines and laboratory supplies, patient adherence, antimicrobial resistance, patient safety, product registration, post-market surveillance, product quality, and financing to support evidence-based decisions to manage pharmaceutical services. Funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), our predecessor global pharmaceutical systems strengthening programs first developed several electronic or eHealth tools to support the pharmaceutical management information system interventions. Between 2011 and 2017, our various pharmaceutical systems strengthening programs funded by USAID (henceforth termed ‘the program’ in this paper) continued to upgrade or establish new digital health technologies. An iterative approach was adopted to address systemic challenges related to data collection, information processing, reporting, and decision-making to support country ownership and sustainability. Through digital health technologies, the program helps ensure that quality pharmaceutical information is available across health systems — public, private, or the faith-based sector, depending on local context — by formulating pharmaceutical policy and plans to monitor supply chain systems and pharmaceutical services. Table I lists the variety of digital health technologies that are relevant to help attain the overall SDG 3 — ‘ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.’ Although the majority of the digital health technologies support targets 3.8 and 3.b., we also list how they may contribute to other relevant SDG 3 targets. The digital health technologies were designed to meet the country’s pharmaceutical management information system needs, were adapted to the local context, and minimized language barriers where relevant, thereby making them widely available in non-English speaking countries. For example, a regional dashboard10 that serves as an early warning system to mitigate stock-outs of HIV/AIDS commodities was originally developed for Francophone countries, adopted an intersectional approach by enabling digital access to transparent information cutting across lines of authority, and facilitate decision-making at all levels across the West Africa region.11–13 In Afghanistan, the program catered to the relevant information needs of the pharmaceutical system and adapted the processes to meet local health workers’ relevant skill sets.14 In 2015, in response to the demand for active drug-safety monitoring in patients undergoing arduous treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis, the program developed a pharmacovigilance monitoring system.15 This is a web-based application used by clinicians, regulatory bodies, and implementing partners to monitor the safety and effectiveness of new medicines conditionally approved for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis.16

Table I.

Digital health technologies to support access to medicines and pharmaceutical services.

| Digital Health Technology (in alphabetical order) | Key Objectives | Countries | Languages | Contribution to SDG Targets (Indicators) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-retroviral treatment patient monitoring and reporting system | Clinical information management system to help monitor patient adherence and track treatment progress | Swaziland | English | 3.3 (3.3.1; 3.3.2) 3.8 (3.8.1) |

| Commodity reporting tools integrated in national DHIS2 platforma,b | Integrated and harmonized commodity reporting for priority public health programs in the era of country-level decentralization23 | Bangladesh, Kenya | English | 3.3 (3.3.1;3.3.2; 3.3.3) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| Commodity Tracking Systema http://www.lmis.org.sz/index.php/en/ | Easy accessibility and visibility of consumption data at all levels; patient management24 | Swaziland | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (3.3.1;3.3.2;3.3.3) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa Health Community TB Supply Chain portala,c http://ecsascportal.org | Regional information sharing and mitigating risk of stock-outs, overstock, expiries, etc.25 | Introduction planned in 20 member countries: Botswana, Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, Seychelles, South Sudan, Somalia, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe | English, French, Portuguese | 3.3 (3.3.2) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| Electronic Dispensing Toola,b | Medicine stock management and dispensing; treatment adherence tracking; pharmaceutical services26 | DR Congo, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Guyana, Haiti, Kenya, Morocco, Namibia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Togo, Zambia | English, French | 3.3 (3.3.1; 3.3.3) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| Essential Medicines Electronic Accessa https://emela.org.za | Provides healthcare professionals with easy access to up-to-date information on Adult Standard Treatment Guidelines and essential medicines; includes smartphone application | South Africa | English | 3.3 (3.3.1;3.3.2; 3.3.3; 3.3.4) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Essential Medicines List; Licensed Medicines Listd | A system to ensure that only medicines of assured safety, quality, and efficacy are listed and licensed for public and private sectors – key reference for medicines regulatory authority | Afghanistan | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| e-TB Managera,e Current version with one of four modules available at http://www.etbmanager.org/ | Web-based patient management of TB; medicines and laboratory data management; free version in development27 | Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Cambodia, Indonesia, Namibia, Nigeria, Ukraine, Vietnam | Armenian, Azeri, Bangla, Portuguese, Khmer, Indonesian, English, Ukrainian, Vietnamese | 3.3 (3.3.2) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| International Medical Products Price Guidef http://mshpriceguide.org (open-access) | Makes price information more widely available in order to improve procurement of quality-assured medicines for the lowest possible prices | 172 countries | English, French, Spanish | 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| IRPd | Time series analysis of pharmaceutical supply management and rational medicine use indicators in 18 of 34 provinces | Afghanistan | English | 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Kenya Clinical Guidelinesb http://kenyaclinicalguidelines.co.ke/ Portal encourages reporting of adverse drug reactions and poor quality medicines | Mobile technology to increase access to and use of clinical guidelines to improve prescribing; platform allows guidelines to be updated | Kenya | English | 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) |

| MOHFW Supply Chain Management Portala Includes six major interactive digital tools and dashboards -Product catalogue -Procurement plan and tracker -Drug registration database -Asset management system -Family Planning LMIS -Maternal & Child Health LMIS https://www.scmpbd.org/ | One-stop source for procurement and logistics information; includes evidenced-based asset management system;28 the procurement tracker promotes good governance, transparency and competition in the bidding process29 | Bangladesh | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| OSPSANTEa https://ospsante.org | Web-based dashboard for managing essential health commodities logistics and patient information under a single platform30 | Mali, Guinea, South Sudan | French, English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (3.3.1; 3.3.3) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| OSPSIDAa https://www.ospsida.org | Pharmaceutical management information dashboard for West Africa region; aggregates data on HIV/AIDS commodities10 Managed by West Africa Health Organization | Implemented in: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Guinea, Niger, Togo; Advocacy ongoing for ECOWAS member countries: Cape Verde, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leona, Senegal, The Gambia | French, Portuguese, English | 3.3 (3.3.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| Pharmaceutical Dashboarda http://slpharmadb.org/ | Early-warning system to avert stock-outs; visual display of dispensing and aggregated patient data of priority public health programs | Sierra Leone | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| Pharmaceutical Information Dashboarda http://pmis.org.na | Pharmaceutical service performance indicators; medicines dispensing data; stock status of essential medicines, vaccines, commodities and clinical supplies31 | Namibia | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Pharmaceutical Information Portalg | Data warehouse and business intelligence system; uses key pharmaceutical service indicators and medicines availability data | Uganda | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Pharmaceutical Logistics Information System (includes data from mSupply)d | Analysis of past medicine consumption by volume and value; data contributes to budget planning for National Health Accounts | Afghanistan | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Pharmaceutical Registration Information Systemd | Registration database on pharmaceutical products, suppliers, and manufacturers | Afghanistan | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Pharmaceutical Service Management Dashboarda http://perseus.org.za/ | Monitor pharmaceutical service delivery for access to medicines | South Africa | English | 3.3 (3.3.1; 3.3.2) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| Pharmacovigilance Automated Information Systema | Facilitates adverse drug reaction reporting; assists in causal relationship examinations; automates generation of signals on potential threats to medicine use; reports efficacy issues32 | Ukraine | Ukrainian | 3.8 (3.8.1) |

| Pharmacovigilance Electronic Reporting Systemb http://www.pv.pharmacyboardkenya.org/ | Reports suspected adverse drug reactions and suspected poor quality medicinal products; online and mobile apps available33,34 | Kenya | English | 3.8 (3.8.1) |

| Pharmadexa | Registration of pharmaceutical products and market authorization holders; facilitates post-market inspection and import permits/licensing35 | Bangladesh, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Namibia | English, French, Portuguese | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Portal, Directorate General of Drug Administration, Ministry of Health and Family Welfarea http://www.dgda.gov.bd/ | Portal for registered pharmaceutical products, suppliers, manufacturers, drug stores, and reporting of post-market surveillance of medicines | Bangladesh | English | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Private Pharmacy Outlet Registrationd | Database of private pharmacies and wholesalers; contains information on service quality standards for regulators and consumers | Afghanistan | Dari | 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| PViMSa | Supports both active surveillance and spontaneous reporting features to monitor safety of medicines with data management features15 | Georgia, Philippines | English | 3.8 (3.8.1) |

| QuanTBa,c http://siapsprogram.org/tools-and-guidance/quantb/ (freely downloadable) | Quantification of TB medicines36 | Downloaded by 134 countries; Technical assistance on implementation provided for: Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, DR Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Kenya, Mexico, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Philippines, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Uganda, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Zambia, Zimbabwe | Chinese, English, French, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish | 3.3 (3.3.2) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.3) |

| Quantimeda,b,g,h | Quantification of essential medicines and supplies37 | Afghanistan, Angola, Bangladesh, Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, DR Congo, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Guinea, Guyana, Haiti, Kenya, Mali, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nigeria, Panama, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia, Zimbabwe | English, French, Portuguese, Spanish | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (3.3.1; 3.3.3; 3.3.5) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| RxSolutiona,g | Pharmaceutical stock management and dispensing; pharmaceutical services38,39 | Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Uganda | English, French | 3.1 (3.1.1) 3.2 (3.2.1; 3.2.2) 3.3 (all indicators) 3.4 (3.4.1) 3.5 (3.5.1) 3.7 (3.7.1) 3.8 (3.8.1) 3.b (3.b.1; 3.b.3) |

| Sentinel Site-based Active Surveillance System for Antiretroviral and Anti-TB treatment Programsa | Documents and quantifies adverse events; determines risk factors; patient adherence40 | Swaziland | English | 3.8 (3.8.1) |

| TB Warehouse Inventory Management Systema | Supply planning for TB commodities | Bangladesh | English | 3.3 (3.3.2) 3.8 (3.8.1) |

The digital health technologies listed in Table I were or are implemented by Management Sciences for Health and its partners through various donor-funded projects.

USAID, Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services Program (Global); 2011–2017

USAID, Health Commodities and Services Program (Kenya); 2011–2016

USAID, Challenge TB Project (global); 2015–2019

USAID, Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems Program Associated Award Project (Afghanistan); 2011–2017

USAID, TB Care 1 (Cambodia, Indonesia, Vietnam) 2010–2015; USAID Challenge TB (Nigeria) 2015–2019; USAID Health Information

Policy and Advocacy Project (Cambodia), Palladium Group; 2014–2018

Currently funded by Management Sciences for Health; historically by Rockefeller Foundation; Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency; Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through Strategies to Enhance Access to Medicines project.

USAID, Uganda Health Supply Chain Program; 2014–2019

U.S. Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Supply Chain Management System Project; 2005–2016

DHIS2: District Health Information System 2; IRP: Inventory management assessment tool, Rational medicine use, and Pharmaceutical management tool; LMIS: Logistics Management and Information System; MOHFW: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; OSPSANTE: Outil de Suivi des Produits de Sante; OPSIDA: Outil de Suivi des Produits du VIH/SIDA; PViMS: PharmacoVigilance Monitoring System; SDG: Sustainable Development Goal; TB: tuberculosis; USAID: US Agency for International Development

An intersectional approach for e-TB Manager, a tool for tuberculosis surveillance, systematically promoted south-to-south technical assistance from Brazil to nine countries for knowledge sharing and addressed infrastructure, language, and age barriers for widespread use. In countries such as Nigeria, Indonesia, and Ukraine, many public-sector health workers, including physicians, had never used a computer before and did not have privileged access to training programs that later became possible due to e-TB Manager.17 Poor internet connectivity, limited computer infrastructure, and intermittent electricity can be major deterrents for digital health technologies, particularly at the district level. For example, the program installed 24 solar power kits in 10 priority districts in Bangladesh to power continued use of e-TB Manager.18 Strong leadership and an official government mandate for the use of e-TB Manager, effective adult learning methodologies for computer novices,19 and a steady five-year period enabled Ukraine to be the leader among all implementing countries, as demonstrated by its extensive nationwide diffusion of e-TB Manager by 2015, comparable to what Brazil first achieved between 2004 and 2008.20,21 The World Health Organization’s (WHO) digital health for end tuberculosis strategy cited e-TB Manager as an example in contributing to quality patient-centered care and TB program management.22

Data sources

We screened internal project documentation on various digital health tools that provide clarity in the conceptual and implementation approach. The project documentation sources were quarterly reports and annual reports submitted to our funder and ad hoc reports on specific digital health tools developed for knowledge sharing. Unpublished sources, such as training reports, workshop proceedings, and presentations delivered in international meetings, were also reviewed to glean information about the implementation process. No interviews or formal evaluations were conducted for this paper. Taking into account geographic diversity, availability of documentation, and institutional memory of the authors, we present five selected case studies. Our paper will describe the conceptualization and implementation of the dashboard module (Bangladesh – Asia); OSPSANTE, a health products dashboard (Mali – Francophone Africa); the Pharmaceutical Information Portal (Uganda – East Africa); Pharmadex (Mozambique – Lusophone Africa); and the Electronic Dispensing Tool (Namibia – Southern Africa). Drawing from our multi-year institutional experience in more than 20 high disease-burden and resource-constrained countries, we describe how various digital health technologies can contribute to targets 3.8 and 3.b while complementing other targets toward the overall SDG 3 — 'Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.’

Results

Bangladesh: Dashboard module helps reduce contraceptive stock-outs

Increased access to family planning methods in Bangladesh between 2001 and 2014 decreased the total fertility rate by 23% (from 3.0 to 2.3 births per woman) and the maternal mortality ratio by 40%.41 Additionally, the percentage of married women with an unmet need for family planning decreased from 17% to 12%.42 These achievements are a result of multiple factors, including improved socioeconomic status, women’s employment, and health system improvements. As part of the Family Planning 2020 global partnership commitments, the Government of Bangladesh pledged to reduce the total fertility rate to 2.0 by 2021.43 A high rate of unintended pregnancies is associated with stock-outs and a lack of real-time information at all levels of the supply chain.44,45 To maintain the reduction in the fertility rate, women and their partners must have uninterrupted access to a range of safe, high-quality contraceptives across 29,200 service delivery points.

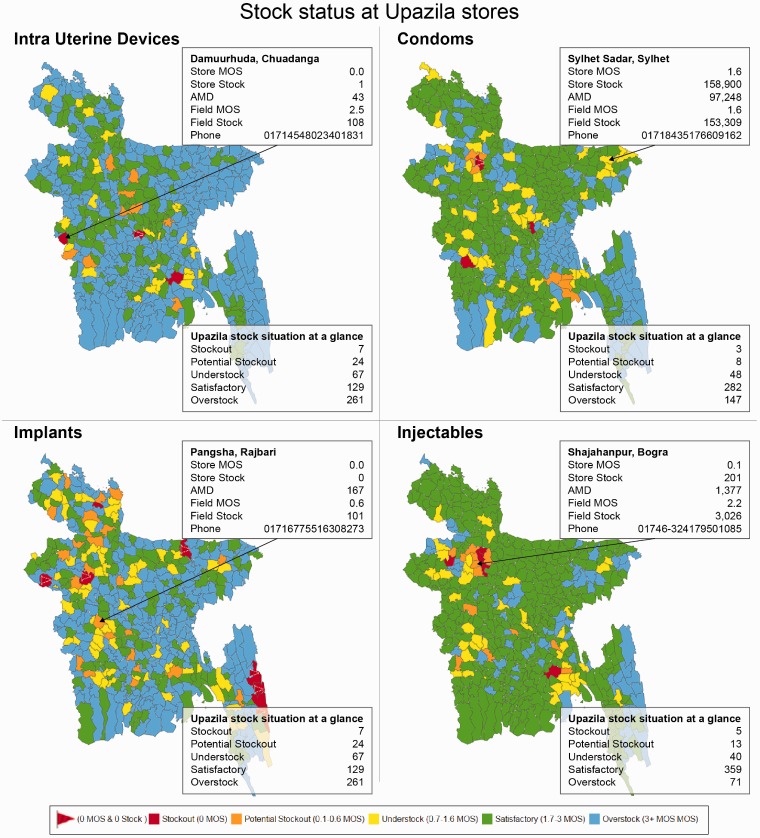

In this context, the program, in partnership with the Government of Bangladesh’s Directorate General of Family Planning, introduced the first public-sector electronic logistics management information system in 2011, which collects aggregated data and provides real-time information on the availability of contraceptives at the sub-district level.46 This system also involves NGO-managed health facilities, but not the private sector. The electronic logistics management information system empowers managers to take appropriate action to avoid stock-outs and plan for more accurate procurement and distribution compared to the paper-based reporting systems.47 However, a 3%–4% stock-out rate persisted at some service delivery points. The bottleneck was the unavailability of disaggregated facility and provider information to link with national-level programs. To address this, in 2014, the electronic logistics management information system was enhanced by implementing a nationwide web-enabled dashboard module with easy-to-understand charts, GIS maps, and tables to track stock levels at the regional and sub-district levels (Figure 1).48 After a year, uptake of these data for decision-making at all levels was limited. Therefore, Short Messaging Service was incorporated to alert health workers and supervisors across all 29,200 service delivery points to potential stock-out or overstock situations for contraceptives so they could initiate prompt action. To facilitate data transparency and accountability, the government established and funded a national steering committee. Government leadership also designated the dashboard module as ‘open access’ to make stock-out data publicly available.

Figure 1.

Upazila level dashboard module in Bangladesh for family planning commodities.

This is an example of the dashboard module hosted at the Supply Chain Management Portal of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. The data visualization allows users to quickly spot stock status and obtain upazila store contact information for remedial action. Stock situation at a glance provides summary information among all 488 upazilas.

AMD: average monthly distribution; MOS: months on stock; upazilas: sub-districts of Bangladesh (n = 488).

Through coordination of the forecasting working group and other stakeholders, data from the dashboard helped the government reach consensus to not procure 410,000 implants for fiscal year 2014–2015. This saved approximately US $4.1 million.49 The dashboard progressively enabled local-level managers to transition from data producers to data users and has improved decentralized decision-making to reduce stock-outs. As a result of this real-time access to data, periodic check-ins by national-level supervisors have enabled progressive improvement in data quality and accuracy at the service delivery point level, as observed by program staff. Hands-on training was provided on the use of data for timely decision-making and planning. Because the phone numbers of all 29,200 service delivery points are accessible through the dashboard module, communications have become easier, and potential red-flag situations may be easily resolved in a timely manner. The stock-out rate has remained at <2% since June 2015. Although not directly attributable, this initiative, along with the government’s multi-pronged interventions and other projects that have contributed to increased availability of contraceptives, helped avert approximately 5 million unintended pregnancies in 2016 and prevented 5,000 maternal deaths.50 Staff’s lack of analytical capacity, limited decision-making authority for local-level managers, and a weak culture of using data remain barriers to the optimal use of the dashboard. However, this dashboard serves as a national advocacy tool for rationalizing investments and fosters dialogue among stakeholders and donors. As a result, Bangladesh became the first country to commit to the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition’s Take Stock campaign to reduce stock-out rates from 2% to 1% at the service delivery point level.51

Mali: A new, web-based early warning system for priority public health programs

In 2011, the chief pharmacist of Mali’s Ministry of Health requested on-demand digital access to information on the availability of medicines and commodities in public health programs, namely family planning, malaria, and maternal and child health. At that time, Mali’s public sector had no digital system for logistics management, and the monthly reporting rate from health facilities using the existing paper-based logistics management information system was very low (10%). It took an average of six months for information to flow from a district to the national level. In 2012 and 2013, after redesigning the logistics management information system, the monthly reporting rate increased to 40% by 2014. This was a necessary step before designing and implementing a digital system in the public sector.

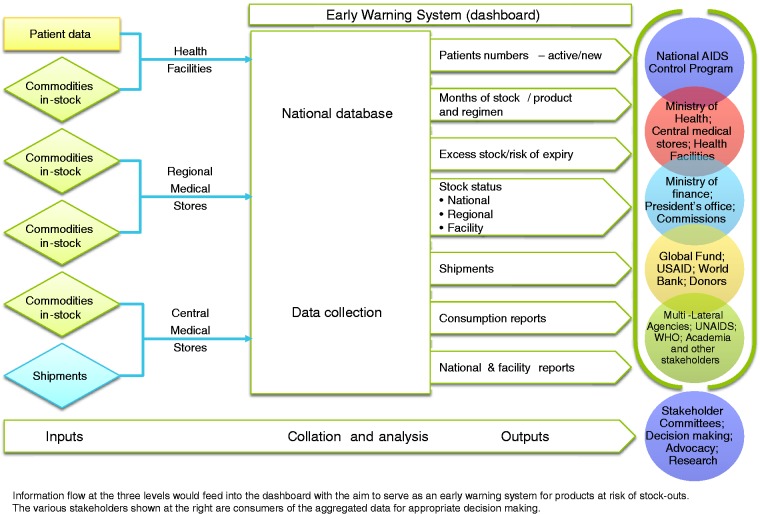

In 2014, an assessment of data and reporting needs was conducted to help design a web-based early warning system for priority public health programs to support evidence-based decision-making. The digital approach was expected to improve inventory management, data recording and transmission, ordering, and the availability of health commodities at all levels of the health system. A south-to-south collaboration was facilitated by bridging the Bangladesh-based information technology (IT) engineer who supported the development of the dashboard in Bangladesh with authorities in Mali. Figure 2 illustrates the conceptual design of the dashboard, which was named ‘Outil de Suivi des Produits de la Santé’ (OSPSANTE).

Figure 2.

Conceptual design of OSPSANTE.

OPSANTE: Outil de Suivi des Produits de Sante.

Appendix A, Table A1 lists the key approaches for implementing OSPSANTE. By 2015, OSPSANTE had been rolled out in 1,200 health facilities and 8 warehouses in 50 districts covering six regions in the South, excluding three regions in the North that were undergoing conflict. The monthly reporting rate of 40% with the prevailing paper-based system increased to 98% with OSPSANTE (see Table II for key results). Periodic check-ins by national authorities identified ongoing challenges and developed solutions. For health facilities experiencing poor internet connectivity, an offline option was offered for data entry into Microsoft Excel with the capability to upload the file into a compatible platform in OSPSANTE. When inconsistencies in data reporting were observed, support was provided to ensure the accuracy and completeness of reporting.

Table II.

Key results after introducing OSPSANTE.

| Theme | Key Results |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder coordination and transparency | • Better coordination among Mali’s public health programs, international development partners, donors, and civil society owing to real-time access to information. Twenty-six civil society organizations were empowered to use data from OSPSANTE and contribute to oversight and accountability of commodities and medicines. |

| Reduction of stock-outs | • Before OSPSANTE, there was an average commodity stock-out of 50% in 2013. After OSPSANTE, this decreased to an average of 28% in 2016. |

| • An end-user verification study was conducted in 78 facilities, including 24 storage facilities, in August 2016. All health facilities had at least one presentation of AL on the day of the visit, and 78% had four presentations. The percentage of health facilities stocked-out for 3 d or more in the previous three months ranged from 0% to 29%, depending on the commodities. | |

| Re-allocation between commodities | • A total of 11,250 rapid diagnosis tests were transferred from one health facility to another. Similarly, 4,800 AL 6 x 1 tablets were transferred to address the situation of overstock as well as the threat of medicines expiry. |

| • To mitigate anticipated shortages of antimalaria medicines at the central warehouse, an international development partner was asked to rapidly accelerate the transfer of 1 million AL 6 × 4 pack sizes. | |

| Rational pharmacotherapy | • In August 2016, data from OSPSANTE helped verify that 90% (1,958/2,178) of children under the age of 5 y with uncomplicated malaria were treated with the relevant combination therapy following the updated clinical treatment protocols. |

| Additional public health programs | • OSPSANTE’s success was seen in malaria, family planning, and maternal and child health programs. Building on this innovation, OSPSANTE was upgraded to include HIV/AIDS, nutrition, and Ebola-related commodities. |

AL: artemether-lumefantrine; OPSANTE: Outil de Suivi des Produits de Sante

Implementing OSPSANTE required adequately addressing national-level coordination and building the capacity of the government’s stewardship role. The Directorate of Pharmacy and Medicines and the regional Directorate of Health were supported to organize coordination meetings around the stock status of key commodities and management issues by drawing on monthly data from OSPSANTE to foster accountability and decision-making. To promote a culture of data use, the directorate sends a printed monthly bulletin to decision makers that contain analyses of key findings from OSPSANTE with relevant recommendations (Appendix A). Building on this initial experience for priority public health programs, new modules on HIV, nutrition, and Ebola commodities were introduced into OSPSANTE.

The interoperability of OSPSANTE with DHIS2 was recently accomplished with the MEASURE Evaluation project. The source codes were handed over to the Directorate of Pharmacy and Medicines and the National Agency of Telehealth and Medical Informatics to enable them to continue improving OSPSANTE. To ensure continuation of relevant activities, agreement was sought with the Ministry of Health to ensure uninterrupted funding upon withdrawal of the program’s support.

Uganda: Using data warehousing technology and business intelligence to improve medicines management and pharmaceutical services

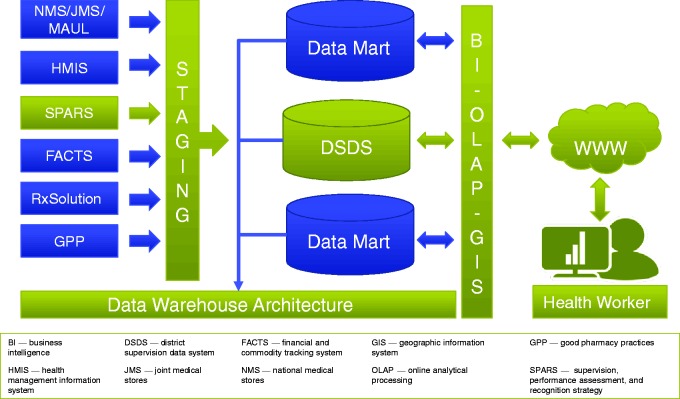

The fragmentation of Uganda’s drug supply chain has resulted in stock-outs and poor provision of pharmaceutical services.52 Existing data were scattered, inaccessible, and of questionable quality, whereas analyses and decision-making were cumbersome. The Uganda Ministry of Health adopted the national supervision, performance assessment, and recognition strategy to improve medicine management at all levels of the health system. The latter strategy is a mentorship approach to gather data from all 3,700 public and faith-based private, not-for-profit health facilities and hospitals in Uganda in five pharmaceutical service areas: dispensing quality, prescribing quality, stock management, store management, and reporting quality for all essential medicines. The data are collected by district-based medicine management supervisors who visit health facilities on a regular basis and analyze findings to make improvement plans for individual facilities.53 Data are collected via an electronic form with offline capability for remote areas and are transmitted online to a national server. Through an extract, transform, and load process, the data are re-organized in a data warehouse (Figure 3) called the ‘Pharmaceutical Information Portal’.

Figure 3.

Conceptual approach for Uganda’s pharmaceutical information portal.

To establish the data warehouse and business intelligence system, the program engaged an east African-based IT firm whose mission was to provide solutions ‘For Africa, By Africa, In Africa’.54 As of March 2017, the portal was receiving 400 comprehensive health facility reports per month and had given access to 626 health workers to run reports, ranging from individual health facility reports to national performance reports. The portal progressively contributed to improved data quality with its extensive quality checks during data entry and improved data use because stakeholders can generate and share national and district reports (Figure 4). This intervention helped public-sector health workers and managers increase their knowledge of computers and other technology to ease communication at all levels and simplify their work. The Ministry’s pharmacy department, technical programs, district health officers, and health workers are using the portal to monitor data, make decisions, and implement follow-up interventions. The national supervision, performance assessment, and recognition strategy report is publicly available on the Ministry website.55

Figure 4.

Pharmaceutical information portal and dashboard in Uganda.

SPARS: supervision, performance assessment, and recognition strategy.

Several other digital health systems are included on the SharePoint platform but have yet to be included in the Pharmaceutical Information Portal data warehouse. The electronic Good Pharmacy Practice 56 system enables easy data entry, data quality checks, and automated report generation of Good Pharmacy Practice inspections by National Drug Authority inspectors who entered 952 reports in 2015. The data warehousing concept permits the Ministry to include many more data sources to streamline reporting. To facilitate the Ministry’s target of a national rollout of RxSolution for all hospitals and health centers to track health facility stock management, the RxBox was developed to make the tool easy to install without much technical knowledge.57 RxSolution permits the generation of medicine consumption data to support procurement decisions. The program, in collaboration with the various United Nations agencies and donors, has contributed equipment and technical assistance to support the Ministry’s goal of national coverage by 2018. As of January 2017, nearly 600 staff had been trained on RxSolution in 186 of the 380 target health facilities. The Ministry has planned for RxSolution to transmit stock status to the Pharmaceutical Information Portal by 2021 as part of the broader digital health strategy for medical records management.58 In addition, the Ministry has begun involving selected private, for-profit health facilities on a pilot basis with the goal of universal involvement of the private sector in the coming years.

Mozambique: Creating an enabling environment for a digital medicine registration system

As in many low- and middle-income countries, Mozambique has a shortage of quality essential medicines that is exacerbated by the average of 400 days that it once took for medicine importers and distributors to receive market authorization. The government staff found it difficult to retrieve huge medicine registration dossiers because the majority were transferred to a warehouse and stored in boxes, making a manual search of documents time-consuming and impractical. It was not easy to obtain historical and detailed information on the more than 4,000 registered pharmaceutical products. The Microsoft Excel-based databases that were commonly used had limited functionality to generate information to properly monitor and evaluate the process and products and to inform results to applicants, such as manufacturers, wholesalers, distributors, stakeholders, and the public. In response, the program collaborated with the Mozambique Ministry of Health’s pharmaceutical department to analyze system requirements, define data elements, and identify a tool that is compatible with local technology and capacity.59 To improve the medicine registration process of the pharmaceutical department’s registration unit, there was focus on two strategic areas (Table III) with a conceptual approach (Figure 5). Details on how the medicine regulatory framework was revised as a precondition before introducing Pharmadex,60 a digital medicine registration system, are provided elsewhere.61 The IT and network infrastructure was upgraded, and a series of trainings was provided to staff on the use of Pharmadex. Use of the dossier review modules and system administration began in October 2015.

Table III.

Strategy for strengthening the medicine registration process through a computerized system.

| Focus Area | Key Approaches |

|---|---|

| Medicine registration process improvement and capacity building | • Train staff to conduct a transparent and scientific review of medicine registration dossiers in compliance with Good Review Practice |

| • Support upgrading/revising the legal framework (e.g., regulations, guidance, templates) on medicine registration and quality management systems | |

| • Streamline the medicine registration process for marketing authorization approval to ensure that it effectively controls the quality of medicines entering the market | |

| Computerize medicine registration process management (Pharmadex) | • A transparent and efficient medicine data tracking system from the submission of applications to marketing authorization |

| • A faster medicine registration process because multiple assessors can review different modules of dossiers simultaneously and share findings using Pharmadex | |

| • More efficient management of the registration life cycle: Registration, amendments, re-registration, post-market surveillance, and corrective actions taken on quality issues |

Figure 5.

Conceptual approach to implement Pharmadex in Mozambique.

CD: compact disk; IT, information technology.

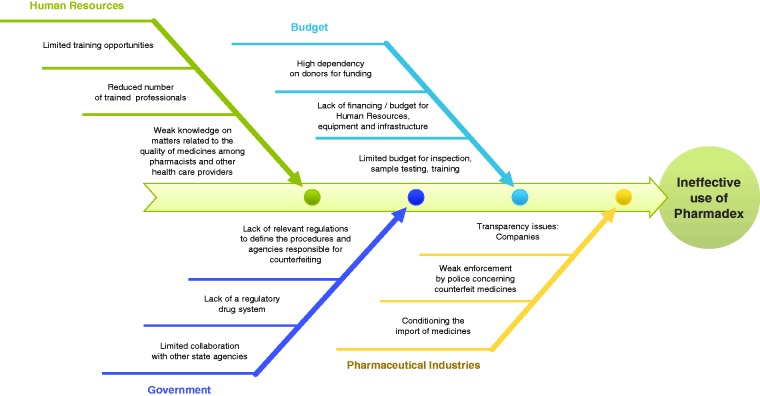

In January 2016, an assessment of the use of Pharmadex by five medicine registration staff showed that they had spent only 36.4 person-hours using Pharmadex out of a cumulative 1,760 person-hours over eight weeks. To determine why staff favored the manual process, an interactive workshop was conducted to have staff identify a matrix of the benefits of and obstacles to using Pharmadex. Staff also identified internal stakeholders, external partners, and strategies to obtain their support (Appendix B). Staff identified four major challenges and their corresponding root causes (Figure 6), developed a 28-point priority action plan, and created a shared mission statement to promote ownership of Pharmadex. The program hired a new IT team that included one technical advisor with medicines regulatory experience and one local IT specialist who was paired with an experienced IT specialist based in Ukraine. A consultant was embedded in the pharmaceutical department to provide on-the-job training and support to ensure fidelity of the process, troubleshoot problems, and report system errors. A monitoring and evaluation plan enabled managers to track the use of Pharmadex on a weekly basis and take appropriate, timely action. Compared to the average of 400 days taken to approve a product registration application prior to Pharmadex, the corresponding process improvements in the regulatory framework decreased that time to 176 days by June 2016. Many lessons were learned concerning the need for disciplined monitoring and evaluation plans for new digital health technology and the importance of strong leadership, systems for accountability and transparency, capacity building, and financing options for maintaining Pharmadex.62 Early adopters of the monitoring and evaluation system saw its benefits. However, others felt challenged in adopting it, as they saw monitoring as a control rather than a quality measure. Avoiding a culture of blame and focusing on finding the root causes of problems and solving them together gradually improved system acceptance.

Figure 6.

Fishbone diagram to identify root-causes of ineffective use of Pharmadex in Mozambique.

Namibia: Electronic dispensing tool for HIV-drug resistance early warning indicators

With the rapid scale up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to reach the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets, ensuring that patients receive the correct medicines in the correct amounts and are carefully monitored for adherence and possible side effects are crucial pharmaceutical service functions in a pharmacy clinic. These functions are particularly important for patients on antiretrovirals because those medicines are potent, expensive, and require close monitoring on how well they perform in complex, life-long treatment regimens. The electronic dispensing tool monitors patients’ adherence to antiretrovirals, dispensing history, regimen and status changes, appointment keeping, and inventory management and help track early warning indicators of HIV drug resistance.63 The conceptual approach and development of the electronic dispensing tool implemented in public-sector and faith-based health facilities is described elsewhere.64 This summary will describe how data from the electronic dispensing tool were used for analysis and to inform policy.

Early warning indicators of HIV drug resistance are a key element of the WHO strategy to minimize and monitor emergence of resistance at facilities in countries that are rapidly scaling up ART. The WHO-recommended early warning indicators are On-time pill pick-up, Retention in care, Pharmacy stock-outs, Dispensing practices, and Viral load suppression. In 2009, when five early warning indicators were piloted at nine ART sites, the analysis was performed using the electronic dispensing tool.65 The early warning indicators were subsequently analyzed in 33 ART sites by 2010.66 In 2012, Namibia utilized the updated WHO guidelines for early warning indicator data abstraction at 50 ART sites. Pharmacy data from the electronic dispensing tool enabled an analysis of Namibia’s first pediatric early warning indicators and supported the HIV program to monitor performance.67 By 2016, the electronic dispensing tool enabled analysis of national early warning indicator data, which provided evidence for the Government to make statements on national progress toward SDG targets 3.3 and 3.8. A trend analysis of early warning indicator data demonstrated that On-time pill pick-up, Retention in care, and Pharmacy stock-outs at adult sites worsened between 2012 and 2014.68 At pediatric sites, On-time pill pick-up and Pharmacy stock-outs also worsened. This tool allows health care workers to identify poor performing sites for follow up with interventions aimed at improving their early warning indicators.69 This includes identifying and tracing ART patients who default from treatment and become lost to follow-up.70 A recent WHO global update acknowledged the benefit of electronic dispensing tool-facilitated early warning indicator monitoring:

This example is important because it illustrates the value of monitoring drug supply continuity at the level where stock-outs most impact patient care. Additionally, it illustrates how a national ART program successfully modified existing record-keeping systems and trained staff to improve documentation, leading to a sustained improvement in record keeping, and allowing on going routine monitoring of these early warning indicators.71

Discussion

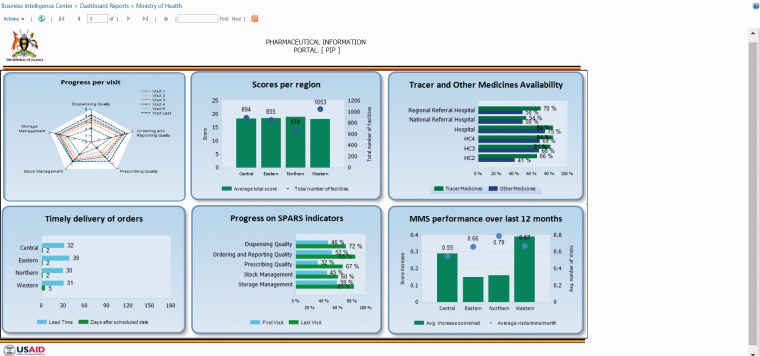

As demonstrated through the five selected country case studies, institutionalizing digital health technologies take years of iterative efforts. Similar to findings from other countries with donor-funded initiatives, a common element across the five case studies is the participatory and collaborative approach with users.72 In addition to government stewardship, there is need to consistently engage diverse stakeholders, actively solicit their input, and engender ownership in the design and implementation. The latter are common elements in all of the case studies presented and are similar to experiences elsewhere.73–74 Although all countries have varied health system characteristics and political economies, a key lesson learned is the need to harness and build on existing governance structures. This meant establishing task forces or committees with the mandate to supervise implementation and hold one another accountable, as illustrated in Mozambique. Routine data — once inaccessible, inaccurate, fragmented, or delayed — are now periodically aggregated and available in real time. If the distribution of aggregated data is through an e-mail list within a country’s public sector, it is limited in scope. As shown in the examples from Bangladesh, Mali, Namibia, and Uganda, the purpose of the dashboard with visual analytics is to ensure that information from multiple sources (Figure 7, for example) is easily accessible to various decision makers at the point of decision-making. Dashboards aim to help monitor trends in medicines availability, pharmaceutical service indicators, and disease-specific treatment trends at various levels in the country’s health system.75 Given the vision of ‘digital Bangladesh by year 2021’ from the Prime Minister’s office,76 the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of Bangladesh made a landmark decision to make its family planning commodities dashboard module publicly accessible. This encourages civil society participation and promotes advocacy. Any public citizen can track the availability of family planning commodities in their district and hold his or her health providers accountable for the services due to the community. Health managers at the district level can use the dashboard as an early warning system for potential stock-outs, seek support directly from other districts with overstock of certain commodities, and seek immediate interhealth facility transfer, thereby making efficient use of limited resources.

Figure 7.

Process and flow of digital information from various sources to the national dashboard, Namibia.

Given the unique needs of each country and depending on the priorities of the government and the donor, the five case studies illustrate the importance of stakeholder engagement and an iterative process, which are similar to experiences in other studies.77–78 Although the focus was primarily in the public sector, governments have gradually mandated the involvement of the NGO, faith-based, and private sectors, depending on local context. The for-profit private sector is generally ahead of the public sector in its utilization of digital health technologies.79–80 Implementing public-sector processes in the inadequately regulated private sector can be challenging.81 Yet, in countries with a large private sector, such as Bangladesh and Uganda, much work remains to progressively integrate the private sector in the digital health technologies discussed in this paper, which is consistent with other studies.82–83 Our program mandate was to develop local institutional capacity through technical assistance. In that regard, the capability of the local IT company in Bangladesh was enhanced to meet the needs of the Government of Bangladesh and was subsequently expanded to Mali and other countries. Similarly, the capability of the IT company based in Ukraine was developed to serve the needs of our programs in Ukraine, the eastern European region, and later Ethiopia and Mozambique. In our experience, the benefits of this south-to-south technical assistance model include significantly lower cost, transfer of implementation experience from one resource-constrained setting to another, and rapid understanding of local context to deliver tailored interventions that draw on lessons from other low-resource settings. For example, the adoption of OSPSANTE in Mali took place within two years of when the program shared its implementation experience in Bangladesh and other countries, which helped to address stakeholder concerns about internet connectivity issues and the need for low-bandwidth, web-based dashboards.

Setting the stage for advocacy, policy, and future research

Accessible data from digital health technologies have the potential to support both internal and external advocacy. Internally, the Ministry of Health can easily access visual analytics of key performance indicators and advocate for more resources or additional funds from its Ministry of Finance and/or from the Office of the President for priority public health programs. Externally, Ministry of Health representatives can rapidly access needed data on demand and utilize those data to advocate for needed support from the World Bank; Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria; donors; and other international development partners. However, for any advocacy to occur and be sustained, establishing trust in timeliness, accuracy, and reliability of the information generated is crucial.84 As seen in the OSPSANTE implementation in Mali, the Ministry of Health’s public health program quantifies needs, the central medical stores procures medicines, the Ministry of Finance and donors provide funding, and multi-lateral development partners support program implementation. The Ministry of Health or the priority public health program plays the stewardship role by coordinating and making decisions based on processed information. In countries that lack trust and understanding, government entities and development partners alike may have different perspectives.85–86 For example, if patient- and medicine-related data and indicators are significantly different among the various stakeholders involved, it potentially sows doubt and delays decisions. WHO’s interministerial policy dialogue emphasized digital health data standardization and the need to cultivate mutual trust and coordination among all stakeholders.87

Given the program’s cumulative, global experience in a wide range of resource-constrained settings and consistent with a recent systematic review, we note that use of data for decision-making at all levels needs to be cultivated and sustained.88 Among the case studies presented in this paper, Namibia is relatively advanced in its periodic use of data for decisions compared to Bangladesh, Mali, Mozambique, and Uganda. In both Bangladesh and Mali, a key lesson learned is that digital tools and dashboards are not an end in itself. In Mali, printed circulars containing analyses of data from OSPSANTE are distributed by the Ministry of Health to encourage users and managers to think about data analysis and its use in planning. In Bangladesh, automated Short Messaging Service text alerts are required to push users to take action based on potential red flag situations. These experiences are similar to those reported by other initiatives that emphasize that progressive improvement in data quality and establishing norms in data analysis among health workers take time.89–90

The next phase of information management development is to build systems to triangulate data from patients, commodities, geomapping, and other parameters of the pharmaceutical system. This is need to provide multiple perspectives, enable decision makers to decipher the root causes of any poor performance in the pharmaceutical system, and design appropriate interventions. Subsequently, countries could aspire to progressively transition from the data triangulation phase to the predictive analytics and data modelling phase for improving patient care, chronic disease management, and supply chain efficiencies, and this must be encouraged from the highest levels of government. For example, following years of investment in various digital health initiatives, Bangladesh recently facilitated an international Data for Decision Making Conference to foster a culture of ensuring data availability, quality, and use for better programmatic and policy decision-making.91 We propose that more research is needed on how decisions are made at various levels, such as the frequency and timing of decisions and their relationship to health outcomes in a given public health program. Recommendations from a systematic review on the effectiveness of dashboards for patient care are applicable for the program’s numerous digital health tools that are now operated by government counterparts.92 A well-defined research agenda must be developed to determine the effectiveness of country- and regional-level dashboards as an early warning system to mitigate stock-outs and ensure availability of medicines, which is a key indicator for SDG targets 3.8 and 3.b.

Historical patient outcomes data and medicine consumption trends from priority public health programs are now available in some of the program’s primary data capture systems but are not necessarily presented in dashboards. This offers countries opportunities to research and utilize findings to inform change in treatment guidelines, inform decision on Ministry of Health program policy, and support tracking progress toward relevant SDG 3 targets. Research must also take into account the aspects of leadership, management, governance, transparency, and accountability, as there are organizational and confounding factors that must be considered in the research design for digital health technologies, as found in Kenya and South Africa.93–94 Finally, while low- and middle-income countries transition to ‘petabytes of digital storage’, a comprehensive governance framework is needed for research and big data analytics to be successful, sustainable, and consistently utilized for decision-making.95

Looking forward: Enabling use of digital health technologies to track progress toward SDG 3 targets 3.8 and 3.b

For the digital health technologies currently utilized to support access to medicines and pharmaceutical services, a thorough review is needed to assess the usability of the aggregated data and indicators to support country voluntary national reviews, as described in the introduction. The Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines for Universal Health Coverage proposed 24 core indicators to complement the SDG 3 indicators. WHO’s core 100 health indicators are intended to reduce excessive and duplicative reporting requirements and guide monitoring of health results nationally and globally, among other objectives.96 Acknowledging the challenges reported by several countries during the recent voluntary national reviews, stakeholders could begin to prioritize gathering key data elements and align their indicators with the SDG indicators. For example, the five selected case studies presented in this paper were established for a given public health program’s needs and reporting requirements in a country, which are not necessarily comparable across countries. The Global Burden of Disease study group’s baseline study of the SDG 3 indicators found that comparable data on the stocking and stock-out rates of essential medicines and vaccines for all facility types (hospitals, primary care facilities, pharmacies, and other health care outlets) and facility ownership (public, private, informal) are not available at present.97 A lack of standardization from divergent sources could lead to inadequate data use as countries track progress toward SDG 3-related targets.

Furthermore, processes and systems for triangulation of data from the relevant digital health technology with other platforms will need to be structured in an ongoing manner. For example, in Bangladesh, various government stakeholders, donors, and international development partners were engaged to establish interoperability of e-TB Manager with DHIS2 to ensure data exchange of key indicators. Likewise, key logistics data are being captured through DHIS2 and are eventually transmitted to the Bangladesh’s Supply Chain Management Portal to inform national-level stock trends and patterns. This is an iterative process with much to learn and accomplish and requires continued cooperation from all stakeholders through government stewardship and political will to track progress toward relevant SDG 3 targets.

Limitations

Our paper is not without limitations. Other than outputs and specific program results, no direct outcomes were measured. A major drawback of our paper is the lack of an external, independent assessment of the selected digital health country case studies presented. The program operated with a mandate for conceptual and procedural digital health implementation. Any monitoring and evaluation initiatives were established on a case-by-case basis depending on the country program’s overall results framework and did not include specific evaluations of digital health tools. No formal evaluation studies were performed for the selected country case studies presented except for Namibia in the context of data use as an early warning system for drug resistance. The program’s external and independent evaluation for USAID reviewed some of our digital health tools in selected countries in the broader context of our efforts in strengthening pharmaceutical systems but did not perform any measurement. The external evaluation credited the program’s efforts in supporting country leaders on aspects of governance and large-scale deployment of digital health tools.98 However, we believe that our programmatic implementation experience on digital health technologies for access to medicines in a variety of country settings may be of interest to readers, particularly in the context of SDG 3 measurement. We hope that our work with country authorities will be picked up by researchers interested in conducting evaluations of digital health technologies, especially in some of the research areas outlined in this paper.

Conclusion

As presented in the case studies, the level of engagement with users and stakeholders was resource intensive and required an iterative process to ensure successful implementation. Ensuring user acceptance, ownership, and a culture of data use for decision-making takes time and effort to build human resource capacity. Global stakeholders must work with country authorities to establish appropriate and harmonized measurement frameworks with a particular focus on enabling the compilation of disaggregated data on relevant SDG 3 indicators. Only then will Ministries of Health and other government authorities realize the full potential of digital health technologies to appropriately track progress toward the SDG 3 targets, beginning with the next voluntary national reviews.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix A and B for Digital health technologies to support access to medicines and pharmaceutical services in the achievement of sustainable development goals by Niranjan Konduri, Francis Aboagye-Nyame, David Mabirizi, Kim Hoppenworth, Mohammad Golam Kibria, Seydou Doumbia, Lucilo Williams and Greatjoy Mazibuko in Digital Health

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following program staff for their significant contribution in the design and implementation of the selected digital health technologies described in this manuscript: Md. Abdullah and Azim Mohammad Uddin (Bangladesh); Constance Toure and Yaya Coulibaly (Mali); Tom Opio and Petra Schäfer (Uganda); Florência Cumaio Moises and Neusa Bay (Mozambique); Samson Mwinga and Stanley Stephanus (Namibia). We thank the countless staff representing the Ministry of Health in various countries for their successful collaboration in implementing various digital health systems. We appreciate Mahmudul Islam of Softworks Bangladesh for his high-quality technical support in the design and implementation of various digital health technologies suitable for resource-constrained settings. Marsha Salinas of Management Sciences for Health is appreciated for her graphics support and Susan Gillespie for editing the manuscript. The authors thank the peer-reviewers for their feedback, which enabled us to greatly strengthen the paper.

Contributorship

NK conceived the study and led the content analysis of various digital health technologies in resource limited settings. FAN and DM provided critical intellectual inputs in the discussion section and other portions of the manuscript. KH, MGK, SD, LW and GM each contributed to their respective country case study presented in this manuscript. NK prepared the first draft of the manuscript and all authors reviewed, provided inputs and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None

Ethical approval

N/A

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID, Washington DC, USA) Cooperative Agreement Number AID-OAA-A-11-00021. No funding bodies had any role in the analysis or decision to publish. The findings, opinions and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of Management Sciences for Health, the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceutical and Services Program, USAID, or the US Government.

Guarantor

NK

Peer review

This manuscript was reviewed by two individuals who have both chosen to remain anonymous.

Supplemental Material

The online supplementary material is available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/2055207618771407.

References

- 1.United Nations. SDG Indicators. Revised list of global sustainable development goal indicators. March 2017. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0pZamHK.

- 2.Wirtz VJ, Hogerzeil HV, Gray AL, et al. The Lancet Commission. Essential medicines for universal health coverage. Lancet 2017; 389(10067): 403–476. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31599-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner AK, Quick JD, Ross-Degnan D. Quality use of medicines within universal health coverage: challenges and opportunities. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 357.DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafner T, Walkowiak H, Lee D, et al. Defining pharmaceutical systems strengthening: concepts to enable measurement. Health Policy Plan 2017; 32(4): 572–584. DOI: 10.1093/heapol/czw153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations. Sustainable development knowledge platform. Synthesis of voluntary national reviews. 2016. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=2386 (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0qrk3Rb.

- 6.United Nations. Sustainable development knowledge platform. Review report on Uganda’s readiness for the implementation of agenda 2030. 2016. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=30022&nr=76&menu=3170 (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0qxw1JS.

- 7.United Nations. Sustainable development knowledge platform. Madagascar voluntary national review summary. 2016. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=30022&nr=66&menu=3170 (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0r5WmQy.

- 8.Together 2030. Voluntary national reviews: What are countries prioritizing? In partnership with World Vision. Available at: http://www.together2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/FINAL-Together-2030_VNR-Main-Messages-Review-2017.pdf (Accessed: 2017-08-30) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t7HYfeBb.

- 9.Management Sciences for Health. MDS-3: Managing access to medicines and health technologies. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js19577en/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t19erhQh.

- 10.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Technical brief: HIV and AIDS commodity management tool. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2016. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/publication/altview/technical-brief-hiv-and-aids-commodity-management-tool/english/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0rLsg7R.

- 11.Evi JB, Adu J, Islam M, et al. Transition of the HIV and AIDS commodity management tool (OSPSIDA) to the West African Health Organization and Cameroon: Lessons learned and recommendations. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2016. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/publication/transition-of-the-hiv-and-aids-commodity-management-tool-ospsida-to-the-west-african-health-organization-and-cameroon-lessons-learned-and-recommendations/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0rfxMCi.

- 12.Evi JB, Adu J, Mabirizi D, et al. Stakeholders Meeting on the Use of HIV and AIDS Pharmaceutical Management Information for Faster Decision Making. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the SIAPS Program. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2015. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js22281en/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t1BXC1gF.

- 13.Mabirizi D. Building the capacity of West African countries to ensure uninterrupted availability of antiretrovirals and HIV rapid test kits. Presented at the WHO AIDS, Medicines and Diagnostics Annual Meeting, 2014, Geneva, Switzerland. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/events/SIAPS_PSM_strengthening.pdf (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0rxM0yW.

- 14.USAID Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems Afghanistan Associate Award. Afghanistan: Establishing a logistics management information system for improved decision making on medicines and commodities. 2016. Available at: https://www.msh.org/news-events/stories/afghanistan-establishing-a-logistics-management-information-system-for-improved (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0s4mzQi.

- 15.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Pharmacovigilance Monitoring System – PviMS. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2015. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js22248en/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0sBqoyw.

- 16.World Health Organization. Frequently asked questions about active TB drug-safety monitoring and management (aDSM). Version 3. Geneva, 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/tdr/research/tb_hiv/adsm/faq_adsm_2016.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0sM2JhY.

- 17.Konduri N. Ending tuberculosis in Ukraine: motivated frontline health workers are key in achieving WHO goals. The Lancet Global Health blog, 2015. Available at: http://globalhealth.thelancet.com/2015/12/18/ending-tuberculosis-ukraine-motivated-frontline-health-workers-are-key-achieving-who (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0sRB1Jp.

- 18.Konduri N. Empowerment and sustainability: web-based technology for tuberculosis care. The Lancet Global Health blog, 2016. Available at: http://globalhealth.thelancet.com/2016/10/24/empowerment-and-sustainability-web-based-technology-tuberculosis-care (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0seRuB0.

- 19.Konduri N, Rauscher M, Wang SC, et al. Individual capacity-building approaches in a global pharmaceutical systems strengthening program: A selected review. J Pharm Policy Pract 2017; 10: 16.DOI: 10.1186/s40545-017-0104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konduri N, Bastos LGV, Sawyer K, et al. User experience analysis of an eHealth system for tuberculosis in resource-constrained settings: A nine-country comparison. Int J Med Inform 2017; 102: 118–120. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konduri N, Sawyer K, Nizova N. A user experience analysis of e-TB Manager, Ukraine’s first and only nationwide electronic recording and reporting system. ERJ Open Res 2017; 12: 3(2) pii: 00002-2017. DOI: 10.1183/23120541.00002-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Digital Health for the End TB strategy: An agenda for action. Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/digitalhealth-TB-agenda/en/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0tETJRf.

- 23.Otieno Y. Arunga T. Managing data with DHIS2: Improving health commodities reporting and decision making in Kenya. Health Commodities and Services Management (HSCM) Program. Nairobi: Management Sciences for Health, 2014. Available at: https://www.msh.org/news-events/stories/managing-data-with-dhis2-improving-health-commodities-reporting-and-decision (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0tUQKtd.

- 24.Commodity Tracking System. Swaziland’s Innovative Approach to Improving Access to Quality Logistics Data for Decision Making – Brochure. Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s22005en/s22005en.pdf (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0tNlCe6.

- 25.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Strengthening TB data and commodities management in the ECSA region. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2015. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/2015/08/14/strengthening-tb-data-and-commodities-management-to-the-ecsa-region/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0tdkquw.

- 26.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Electronic dispensing tool technical brief. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2014. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/tools-and-guidance/edt/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0tm3CeD.

- 27.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. e-TB Manager Technical Brief. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2014. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/tools-and-guidance/e-tb-manager/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0ttixuj.

- 28.Kabir, Md Humayun. 2014. Report on sustainability of SCMP. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health, 2014. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/publication/sustainability-plan-of-scmp/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0u7X2aH.

- 29.Kibria M, Hussain Z, Greensides D. Transitioning the supply chain management portal to the government of Bangladesh. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js22489en/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0uGJFfI.

- 30.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. OSPSANTE: A new tool for tracking health commodities in Mali. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2015. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/2015/06/25/opsante-a-new-tool-for-tracking-health-commodities-in-mali/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0uMa6yk.

- 31.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Namibia launches an innovative pharmaceutical management information dashboard. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2016. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/2016/06/27/namibia-launches-an-innovative-pharmaceutical-management-information-dashboard/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26)] Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0uS8wY3.

- 32.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. IT solution for pharmacovigilance supports rational use of quality, safe, and effective medicines. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2017. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/2017/03/15/it-solution-for-pharmacovigilance-supports-rational-use-of-quality-safe-and-effective-medicines/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0ufcoTz.

- 33.Otieno Y. Pharmacovigilance reporting goes digital in Kenya. Health Commodities and Services Management Program, 2013. Available at: https://www.msh.org/news-events/stories/pharmacovigilance-reporting-goes-digital-in-kenya (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0ulknc0.

- 34.Kusu N, Ouma C, Pandit J, et al. Embracing technology in the Kenya national pharmacovigilance reporting system: ‘Kenya goes green’. Health Commodities and Services Management Program. Nairobi: Management Sciences for Health, 2013. Available at: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00K5S6.pdf (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0upg6qj.

- 35.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Pharmadex. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2016. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/tools-and-guidance/pharmadex/ (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0uZzbeg.

- 36.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Quan TB Technical Brief. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2016. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/TechBrief-Tools-QuanTB-10-14-162.pdf (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0uudYML.

- 37.Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program. Quantimed Technical Brief. Arlington: Management Sciences for Health, 2016. Available at: http://siapsprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/TechBrief-Tools-Quantimed.pdf (Accessed: 2017-08-26) Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6t0uz48pB.