Abstract

Purpose

Part of the local hidden curriculum during clinical training of students in the University of Maiduguri medical college in Nigeria, metaphorically referred to as “toxic” practice by students, are situations where a teacher belittles and/or humiliates a student who has fallen short of expected performance, with the belief that such humiliation as part of feedback will lead to improvement in future performance. Through a framework of sociocultural perspective, this study gathered data to define the breadth and magnitude of this practice and identify risk and protective factors with the aim of assessing effectiveness of current intervention strategies.

Materials and methods

Using a mixed method research approach, quantitative data were collected from fourth-year medical students in a Nigerian medical college through a survey questionnaire, and qualitative data were obtained through a face-to-face, individual, semi-structured interview of students attending the same institution.

Results

Findings indicate that many students continue to experience “toxic” practice, with only very few reporting the incidents to relevant authorities, raising important questions about the appropriateness of current intervention efforts.

Conclusion

Current intervention strategies grossly underestimate the influence of institutional forces that can lead to or promote this behavior. Acknowledgment of this has implications for an appropriate intervention strategy.

Keywords: clinical teaching, verbal interactions, belittling, socio-cultural perspective, intervention

Introduction

Conceptual background

A well-known teaching and learning phenomenon is metaphorically referred to as “toxic” by medical students of the University of Maiduguri medical college in Nigeria, which specifically refers to a situation where a clinical teacher belittles and/or humiliates a student who has fallen short of expected performance during a bedside teaching encounter, with the belief that such public humiliation as part of feedback will lead to improvement in future performance. Sharing some similarities to the “pimping” phenomenon described in medical colleges in Western countries, where a medical teacher poses a series of difficult questions in succession to medical students with the objective to teach while maintaining dominant hierarchy,1,2 “toxic” practice has become the norm and part of the local hidden curriculum during bedside teaching encounters in this medical college. This is despite the widespread concern about the adverse impact of such mistreatment of targeted individuals and those who witness the behavior.

The issue of “toxic” practice raised some important issues, and by discussing the issues with colleagues and students, this study may raise some important questions that are of interest to others.3 The author has had the fortunate experience of sharing his thoughts and concerns with the medical college provost and two former departmental chairs on several occasions. This discourse has involved dialogue about the appropriateness of the current intervention strategies in the college to address “toxic” practice. Several questions arose during this discussion that seem to challenge these strategies. Why has the practice not stopped or reduced in frequency although the metaphor seems to express learners’ dislike for the practice? Are there other intervention strategies that can be implemented at the college that will improve the situation? These are the questions that motivated this research.

Literature review

Similar to the practice in medical schools worldwide, students in the clinical period of their program (fourth- to sixth-year students) at the University of Maiduguri medical college in Nigeria undergo most of their training in the medical workplace, at the allocated hospital, where they attend bedside teaching as part of their studies with the aim of developing general medical understanding. Verbal interactions between clinical teachers and learners constitute one of the primary educational activities that occur during such teaching contexts. A prevalent form of such verbal interactions involves clinical teachers asking students questions and passing comments, particularly in situations when learners fell short of expected performance. Often labeled the “Socratic method,” it has been a widespread cornerstone of medical education.4

In order to set the context for this study, a general description of the variant of the “Socratic method” as being practiced in this medical college is offered. The accepted format is that the learner (the medical student) “goes first,”5 where he or she independently assesses a patient and then discusses the findings with the clinical teacher in the presence of the patient, fellow students, resident doctors, and others. During the presentation, discussion sequence is the general format; clinical teachers do, however, interrupt at any time during the learners’ presentation with questions and comments to seek clarification of statements. In most instances, clinical teachers’ comments are reactions to what the learner has offered, and more specifically, they are intended to be corrections to learners’ underperformance.5,6 In effect, they are part of feedback upon which experiential learning depends.7

However, literature indicates that this approach may not be free of problems, and questions are being raised regarding the effects such strategies have upon learning in clinical environments. In fact, despite the known favorable attributes, the clinical teacher–student interaction during bedside teaching encounters has also demonstrated a high incidence of distress in medical students, faculty dissatisfaction, and more particularly the perception of mistreatment among trainees.8,9

Medical student mistreatment is an international phenomenon that has been documented by several studies. In order to identify the extent of this problem, the author of the present study drew upon several studies from different countries. For example, an experience published in the Revista de Chile in 2006 conveyed the reality of medical students at the University of Chile, highlighting that 86.1% of students during their training received two or more abusive incidents.10 The findings further indicated that ~78.1% of the students who suffered abuse reported effects on their mental health and their perception of the doctor being so severe in some cases that 32.2% of them thought about leaving the career.

Another study of 146 final stage medical students from two Australian medical schools, the University of Sydney and the University of Melbourne, examined the interpretations and experience of teaching by humiliation among students during clinical rotations.11 Most reported having experienced (74.0%) or witnessed (83.6%) teaching by humiliation during their adult clinical rotations. The most prevalent behaviors reported were intimidating questioning styles and subtle behaviors, including teachers being nasty, rude or hostile, or belittling or humiliating students. Interestingly, ~30%–50% of the students who had experienced or witnessed teaching by humiliation considered it a useful strategy for learning.

The US surveys on medical students’ experiences of mistreatment and harassment are plentiful, with an important summary of data from 16 nationally representative US medical schools published in 2006.12 Results from 2,316 participants indicate that 42% reported having experienced harassment and 84% experienced belittlement during medical school. These students were significantly more likely to be stressed, depressed, and suicidal, and were significantly less likely to be glad that they were trained to become a doctor. However, only 13% of students classified any of these experiences as severe. In addition, the responses to the Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire in 2011 indicated that one in six medical students reported that they had experienced some form of harassment or discrimination by the end of their fourth year.13

Recently, several studies have addressed this issue and found that medical trainee harassment and discrimination is a widespread phenomenon and has not declined over time. In a study published in 2016, Peres et al14 conducted a cross-sectional study of mistreatment in a medical academic setting in Brazil. Three hundred and seventeen students from the first to the sixth year completed an anonymous web-based survey in which high prevalence of mistreatment was found. Two thirds of the students considered the episodes to be severe, and around one third reported experiencing recurrent victimization. Furthermore, in a recent national survey conducted by the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC) in 2017, 59.6% of medical students in their final year reported being personally mistreated.15

Most of the large medical organizations including World Medical Association16 and AFMC have responded to this issue and identified mistreatment in medicine as a priority area for change.

In a recent study at Nigerian medical school, Oku et al17 found that the most common form of mistreatment experienced by medical students in Nigeria was verbal abuse (57%). Although there are exceptions to this depressing picture of medical education in many countries, it remains valid in portraying the general concern surrounding the context matter in which medical students daily operate. Miller describes:

As medical students, we live in fear, afraid to make mistake, to forget a fact, to appear stupid in front of peers or superiors, or even to cause harm to patients through ignorance.18

Studies indicate that such mistreatment during training creates hostile work environments and induces stress and discomfort, which may impair performance.19–21 Frank et al12 found that medical trainees who experience frequent public harassment were less likely to complete assignments or provide optimal patient care. In addition, trainees who had experienced mistreatment had more emotional health problems, family life problems, and social responsibility disruptions compared with those who had not. In a similar vein, medical students in Nigeria reported stress, fear of the teacher, and reduction in self-confidence as the main effects of experiencing verbal abuse.17,22 It is pertinent to note that few research studies indicate that some stress and anxiety can be beneficial to learning. For example, Vaughn and Baker23 suggested that a certain level of tension and disequilibrium is needed to stretch and challenge students to learn in medical education.

Despite the profound effect of mistreatment of medical students, studies from different parts of the world indicate that less than a third of affected students report such mistreatment incidents to appropriate administrators or bodies.24,25 Studies in Nigeria indicate that only 11.8% of students who had recent experiences of verbal abuse reported the incident or discussed with close associates.17,22 The main reason cited for non-reporting is because it was perceived as a “normal occurrence” by the majority of respondents.

Explanations for medical student mistreatment in the clinical settings have included: the supposedly low position of medical students in a large hierarchical culture of medical training and practice24,25 challenges associated with the use of patients’ bedside for workplace learning;26 the culture of negativity bias in medical education and its influence on feedback mechanism;27 and clinical teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning.28 Other scholars have argued that the lack or limited formal training in teaching skills of a majority of medical educators constitute the most important reason for student mistreatment.29 Notwithstanding these challenges, the credibility of workplace learning in medical education remains high.

Given that verbal abuse and other forms of mistreatment are now widely acknowledged to lead to negative consequences for students, institutions, and society, a key question is how to address these problems. Although it is evident that a range of differing approaches have been employed as intervention strategies to address mistreatment in medical colleges, there are very few success stories. According to the published reports, responses can be categorized as either individual-focused or organization-focused, while the types of strategies employed are remedial, corrective, structural, or procedural.30–33

In individual-focused strategies, remedial and corrective approaches focused on addressing individual behavior have been the most prevalent in addressing mistreatment. For example, Fried et al33 described that the long-term efforts of leaders at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA aimed to eradicate mistreatment. These approaches aimed to reduce mistreatment through educational programs thus increasing awareness and recognition of negative behaviors. As such, they are underpinned by the assumption that mistreatment during clinical training will be lessened if more people know about it, know how to recognize it, and be more assertive in their responses to it. The study, however, demonstrated that even with such a comprehensive multi-pronged set of prevention and interventions, the prevalence of mistreatment did not change significantly.

Critics argue that a major limitation of managing mistreatment as a feature of individual behavior or personality is that little attention is directed toward understanding work groups and organizational factors that enable, reward, or perpetuate the behavior.34 All forms of mistreatment are complex institutional problems, which may manifest at the level of individual behavior.

In an attempt to eradicate mistreatment, some related organizations have also employed organization-focused strategies, including zero tolerance or similar policies.32,34 These policies make prohibitive statements about mistreatment and verbal abuse and provide codes of practice and guidelines on its early identification, management, and prevention. In light of evidence that reports of mistreatment did not significantly decrease in these institutions, the effectiveness of prohibitive policies has been called into question.34 Since mistreatment cases are “he said-she said” in most instances, sanctions can be difficult to justify legally. In this context, those who report mistreatment are said to be viewed as deserving of it and, as a consequence of making the report, experience retribution, or escalated mistreatment.32

Structural interventions focus on preventing the occurrence of mistreatment during clinical training; however, there are relatively few rigorous tests of such interventions in the literature. In an attempt to reduce mistreatment by the acknowledgment of the abuse of power produced by the hierarchical structure in which medicine is practiced, Angoff et al35 tested the efficacy of using workshops as a medium for third-year medical students and advanced practice nursing students to define and analyze power dynamics within the medical hierarchy and hidden curriculum. Although no clear gains were observed across a 13-year period, benefits observed included promoting open dialogue about power and mistreatment in medical education.

Several authors noted that despite these efforts and extensive institutional supports, medical student mistreatment still occurs. By broadening the perspective on workplace learning to include not only students’ perceptions but also the affordances of the workplace and the engagement of individuals,34–36 a deeper understanding of the nature of medical student mistreatment during clinical training from a sociocultural perspective may be possible.

Similar to findings in the literature, a range of different intervention approaches have been employed at the University of Maiduguri medical college in Nigeria to address student mistreatment and in particular “toxic” practice. The approaches include zero tolerance through the establishment of standards for acceptable conduct during clinical training, that is, viewing mistreatment as a breach of college policy; encouraging medical students to report any form of mistreatment to established authority; and corrective and remedial measures for clinical teachers or students involved, that is, viewing mistreatment as a feature of individual behavior or individual personality.30–33

Despite widespread concern, anecdotal evidence suggests that medical student mistreatment remains largely unabated in this medical college, negatively influencing both the well-being and learning of students. This suggests that important aspects of this behavior may have been overlooked and require further elucidation in order to fully address the problem.

Research questions

This study therefore seeks answers to the following research questions:

What is the prevalence of “toxic” practice encountered by fourth-year medical students?

What challenges does “toxic” practice pose for medical students?

What are the factors that facilitate and/or protect the “toxic” practice?

Does the current intervention strategy address the issue of “toxic” phenomenon?

The data discussed in this study were collected as part of a larger inquiry addressing these full set of questions, but this paper reports the findings and recommendations from the first two questions.

Materials and methods

Research strategy

Literature indicates that case study research is an appropriate research strategy where a contemporary phenomenon is to be studied in its natural context.37 Therefore, case study design has been used in this study because it allows the understanding of how and why the behavior occurs in this medical college, shedding light on its sociocultural contexts. The case study strategy is however not without its critics. Eisenhardt38 cited the difficulties in generalizing the research results. The present research is more interested in understanding what happens in a particular setting, and the case study approach facilitates that aim. Furthermore, other medical colleges in relating to situational aspects of this study and recognizing similar issues described can learn from the findings.

Study setting and population

The College of Medicine, University of Maiduguri, is located in a semi-urban town in North-Eastern Nigeria, a resource-limited country. Course delivery is mostly didactic lectures, tutorials, bedside teaching, and emphasis on information gathering as a learning strategy. Similar to most medical colleges in sub-Saharan Africa, majority of teachers in this college have little or no formal training in teaching methods and skills.39–41 The medical students undergo workplace learning at a 530-bed tertiary referral hospital located in the same town. The participants for the study are the 52 fourth-year medical students.

Data collection

Although ideological differences between qualitative and quantitative researchers have existed for almost a century, the integrative methodology or mixed method that is used in gathering data in this study is consonant with pragmatic worldview. In this worldview, the focus is on the problem in its social and historical context, rather than on the method, and multiple relevant forms of data collection are used to answer the research questions.42 Indeed, pragmatists ascribe to the philosophy that the research question should drive the method(s) used, believing that “epistemological purity doesn’t get research done.”43 In line with this, a sequential mixed-method research methodology was used to explore the prevalence and nature of the “toxic” phenomenon; in other words, gathering facts and figures through quantitative method and also seeking clarifications and elaboration of the results of the quantitative data through a qualitative approach to produce a bigger picture behind those data.44

Quantitative data were collected through the use of survey questionnaire. The survey questionnaire, which was five pages long, was developed in consultation with two former departmental chairs and three fifth-year medical students and piloted with another six fifth-year medical students. It included demographic questions, questions about frequency of the mistreatment experienced, reporting and responses to reporting behavior, and effects of behavior on students. Most of them required yes/no responses, and there was a “comments” box in the last page of the questionnaire with the instruction, “If you have any comments that you would like to make please write them in the box below.”

The questionnaire was completed in class group and was labeled with a unique identifying code (MSQ; medical students questionnaire) in order to maintain confidentiality (students did not write their names on the questionnaire). Before handing out the questionnaire, the researcher explained the aims of the research, the students’ right not to participate, and the extent of confidentiality. Edwards and Alldred45 point out the students’ tendency to view completing research questionnaire in class as being “part of schoolwork” and the impact on the choice of participation. Reassurances were continuously given to minimize this effect. To encourage students to work alone and quietly on the questionnaire, they were asked not to discuss the questionnaire until everyone had finished.

The importance of soliciting the perspectives of students while investigating everyday life in schools has been highlighted by some researchers.46 Researchers have also suggested that students can inform schools a great deal about what is needed for change and improvement.47 In line with this, qualitative data were collected through a 30–45 minute individual, semi-structured interview of four fourth-year medical students. Having considered alternative sampling techniques such as random selection48 and purposeful sampling,49 it was decided to lay the responsibility for selecting the interviewees at the feet of the students themselves. In having the power to nominate a group of their peers whom they were comfortable with entrusting with the responsibility of representing their views and interests, students would feel more connected with and represented by the research.50,51

The selection took place by means of a ballot, in which students nominated six class members who stated whether they wished to volunteer as interviewees. Of the students who wished to volunteer, four with the most votes were selected. Students’ interviews were conducted in the classroom during the midday break. The students were interviewed individually by using three open-ended questions. The questions required them to identify the factors that facilitate and or protect “toxic” practice, their knowledge of current intervention strategies, and appropriateness of current intervention strategies. Unstructured follow-up questions were used to encourage further elaboration, which include “What do you mean by that?” “Could you tell me a bit more about that?” “Why is that important to you?” “Could you explain that further?” In many cases, the follow-up questions were more important in eliciting the underlying meanings than the predetermined questions. All interviews were audio recorded.

Data analysis

Data editing was done following the retrieval of the completed questionnaires. The data collected were coded and entered using SPSS version 16. The analysis carried out was univariate (summary statistics) and bivariate (chi square test and Fisher’s exact test). For all statistical analyses of relationships, p-value of <0.05 was accepted as level of statistically significant.

Interview conversations were transcribed verbatim by a commercial transcription service.52 Inductive content analysis (CA) of the data was performed in accordance with the interpretation of qualitative CA described by Graneheim and Lundman53 by using additional tactics for generating patterns of meanings described by Miles and Huberman.43 Codes were identified and were gradually grouped into various categories and eventually into four main themes (Table 6): threatening to learning, traditional practice in the culture of medical education, group and learning environment facilitators, and current intervention strategies.

Table 6.

Themes identified in medical students’ comments during semi-structured interview, with illustrative quotations

| 1. Threatening to learn |

| Example quotation: |

| a. “To me it reflects a lack of teaching expertise by those teachers involved … because it demoralises you and does not help students and the teachers. Possible they don’t know how to teach in any other way.” |

| b. “After being humiliated for the second time, I don’t want to go for the ward rounds sometimes and at the end of the day, I really feel bad about my choice of studying for this career.” |

| 2. Traditional practice in the culture of medical education |

| Example quotation: |

| a. “I get the feeling it’s an age long practice. It’s to motivate you to keep studying, to become confident in yourself. So I think to see how we handle pressure in front of people, what you will face for the rest of your career … I’ve heard colleagues complain about it, but I like it”. |

| b. “This culture of making fun of students in front of your peers and humiliating you because you say the wrong answer has to stop.” “You can only learn so much from a teacher who is friendly.” |

| 3. Group and learning environment facilitators |

| Example quotation: |

| a. “It all boils down to everything, I mean the teachers, nurses, residents and other staff, all professional groups on different occasions exhibit this behaviour and am developing thick skin. For example, some nurses feel superior when a student cannot perform a procedure and humiliated by attending consultant.” |

| b. “You are just new in the clinical year and you are expected to know everything. Competition rather than learning is promoted among us students with bedside questions and belittling. You try to avoid been questioned in front of your peers and other ward staff.” |

| 4. Current intervention strategies |

| Example quotation: |

| a. “They said we can report. Report a teacher that will eventually examine you for promotion? Complain to whom? Students are at the bottom of the ladder in this profession so we get used to it.” |

| b. My own opinion is that the present methods to stop this practice is just a way to show people that, officially, the medical college is doing something about it. Has it stopped it? The answer is No.” |

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Maiduguri Institutional Review Board before embarking on data collection for this study. Participants were informed about the scope and nature of the study and that information disclosed will only be used for the purpose of the study. Written consent was obtained from the participants, and confidentiality was ensured.

Results

Distribution of respondents by sex and age

Of the 52 students, 47 (90%) completed the survey; 51% and 45% were male and female participants, respectively. Majority (46.8%) were in the age group of 26–30 years. Two did not record their sex, and one did not record his/her age group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the respondents by sex and age (N=47)

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 24 | 51.1 |

| Female | 21 | 44.6 |

| Not recorded | 2 | 4.3 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–25 | 15 | 31.9 |

| 26–30 | 22 | 46.8 |

| 31–35 | 9 | 19.1 |

| Not recorded | 1 | 2.1 |

Prevalence and frequency of “toxic” practice

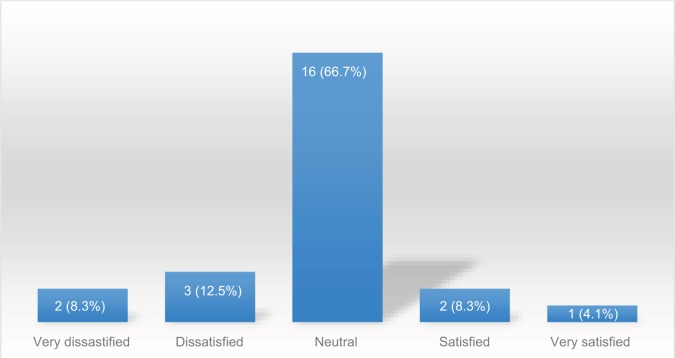

Most (40; 85%) reported having experienced “toxic” practice during bedside teaching encounters with clinical teachers (Figure 1). Frequency of experience ranged from occasionally (50%), once (40%), and frequently (10%) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of “toxic” phenomenon among the respondents.

Table 2.

Frequency of “toxic” experiences among students and their disclosure pattern

| Frequency of “toxic” experiences among respondents | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Once | 16 | 40.0 |

| Occasionally | 20 | 50.0 |

| Frequently | 4 | 10.0 |

| Reporting/discussing toxic experiences | ||

| Report to someone | 24 | 60.0 |

| Did not report | 16 | 40.0 |

Pattern of “toxic” practice disclosure among respondents

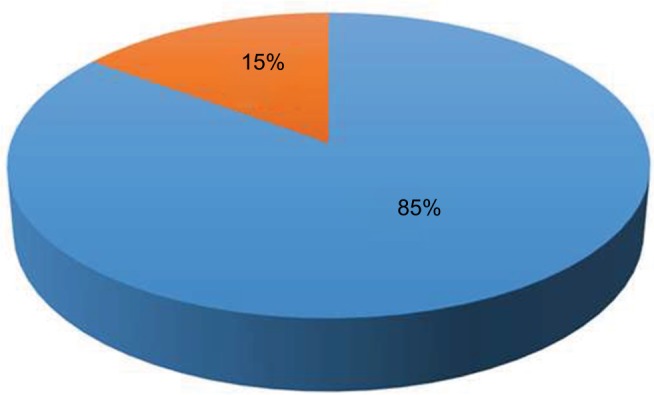

Sixty percent of students who experienced “toxic” practice reported the incidence (Table 2). However, approximately four of every five students in this category reported to their fellow students (Table 3). Only one student reported to faculty or administrators. Among those who did not, most (43.8%) indicated that the incident was not important enough to report. The other common reasons for not reporting episodes were felt nothing would be done about it (25%), resolved the issue by myself (25%), and fear of reprisal (18.8%) (Table 4). Overall, majority (66.7%) of students who reported “toxic” experience felt neutral to the outcome of reporting while only three (12.5%) were satisfied/very satisfied with the outcome (Figure 2).

Table3.

Pattern of “toxic” disclosure among respondents by sex

| People reported to | Sex

|

Total

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male

|

Female

|

Missing sex

|

||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Dean of students | 1 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Designated counselor/hall master/matron | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other medical school administrators | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Faculty member | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Fellow students | 11 | 84.6 | 8 | 89.8 | 2 | 100.0 | 21 | 87.4 |

| Parents | 1 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.2 | ||

| Friends | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Total | 13 | 54.2 | 9 | 37.5 | 2 | 8.3 | 24 | 100.0 |

Table 4.

Distribution of respondents by their reason for not discussing their “toxic” experience by sex

| Reasons | Male

|

Female

|

Total

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| The incident did not seem important enough to report | 4 | 44.4 | 3 | 42.9 | 7 | 43.8 |

| I resolved the issue myself | 3 | 33.3 | 1 | 14.3 | 4 | 25.0 |

| I did not think anything would be done about it | 3 | 33.3 | 1 | 14.3 | 4 | 25.0 |

| Fear of reprisal | 2 | 22.2 | 1 | 14.3 | 3 | 18.8 |

| I did not know what to do | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 28.6 | 3 | 18.8 |

Figure 2.

Level of satisfaction of “toxic” victims with the outcome of their disclosure after disclosing.

Perception of respondents on the adverse effects of “toxic” practice

Two of every three students who experienced “toxic” practice stated that the experience had adverse effects on them. The frequency of responses regarding the effects of “toxic” practice is shown in Table 5. The effects were both personal and educational. Negative feelings toward the clinical teacher (62.5%), felt anger/rage (37.5%), and made me miserable and depressed (29.2%) were the predominant personal effects while the experience made the clinical posting uncomfortable (58.3%) and that it created poor learning environment (33.3%) were the common educational effects stated by the respondents.

Table 5.

Perception of respondents on the adverse effects of public belittlement on students

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Belittlement behavior had adverse effects (N=40) | ||

| Yes | 24 | 60.0 |

| No | 16 | 40.0 |

| Reasons why belittlement had no adverse effect (N=16) | ||

| I thought it is not an offensive behavior | 2 | 12.5 |

| I thought it will make me study harder | 6 | 37.5 |

| It is part of the culture of medical education | 7 | 43.8 |

| Made me stronger | 6 | 37.5 |

| Verbal abuse is part of the culture of bringing up children | 0 | 0.0 |

| I will also do the same if I become a clinical teacher | 0 | 0.0 |

| Adverse effect of public belittlement on students (N=24) | ||

| Made me miserable and depressed | 7 | 29.2 |

| Felt anger/rage | 9 | 37.5 |

| Caused stress | 3 | 12.5 |

| Created poor learning environment | 8 | 33.3 |

| Negative feelings toward the clinical teacher | 15 | 62.5 |

| Made the posting uncomfortable | 14 | 58.3 |

| Resort to alcohol/smoking | 2 | 8.3 |

| Caused depression | 5 | 20.8 |

On the contrary, 16 students stated that the experience had no adverse effects on them. Of this 16, 43.8% felt “toxic” practice was a normal part of training in medical education, 37.5% felt it is useful for learning and also 37.5% felt it would make them stronger.

Qualitative study findings

Table 6 summarizes the findings of the semi-structured interview.

Discussion

Combining validated questionnaires with in-depth interviews has made it possible to triangulate the findings to address two of the research questions:

What is the prevalence of “toxic” practice encountered by fourth-year medical students?

What challenges does “toxic” practice pose for medical students?

Quantitative methods in the first part of this study allowed a larger number of medical students to provide opinion. However, data from student interview in the qualitative phase have clarified some of the issues raised in the quantitative survey.

Clinical education is a crucial part of health professional training.9,22 However, it can also be a time of increased stress for students.9 Data from the present study provide evidence that many students in this medical college continue to experience public belittlement or humiliation, since about 85% of the survey respondents had experienced this form of mistreatment. This result is comparable with the figures reported in most other previous studies,10–12 but higher than results stated by two other studies6,8 which reported <60% of student mistreatment.

These findings are also consistent with the existing research, in terms of the fact that a large proportion of the students reported experiencing this behavior at some time as part of feedback received at bedside teaching encounters (“toxic” practice). Furthermore, the students’ description suggests that there was a pervading culture they found intimidating, rather than specific incidents:

The general impression is that on a bad day … you sort of can’t get a question right at the patient bedside, you get dressed down in front of everybody. I don’t know why. It does seems over here when you do the right thing it’s only to be expected, and when you do something incorrectly – they make you feel inadequate rather than encourage building you up. [Student quote]

Clearly, there is no doubt that the culture of “toxic” practice is still very much present despite the current intervention efforts to prevent it.

However, not everyone agrees that student mistreatment during bedside teaching encounters is common. This researcher heard that some educators in this college say that such mistreatment reports are nonsense; they are only students’ perceptions, not reality. In addition, a significant proportion of students affected (40%) in this study view “toxic” practice as a useful pedagogical tool in medical education or that it made them stronger to face the challenges of practicing medicine.

It’s to motivate you to keep studying, to become confident in yourself. So I think to see how we handle pressure in front of people, what you will face for the rest of your career … I’ve heard colleagues complain about it, but I like it. [Student quote]

This finding adds to those reported by Musselman et al54 who identified “good intimidation” as being related to whether there was a perceived purpose, positive effect (pedagogic or clinical), or necessity for the behavior. In line with this, Seabrook55 suggests that student mistreatment may have positive functions within the culture of medicine that allow it to continue.

Recognizing that some of these augments may be valid, the impact of student mistreatment is however significant. Several recent articles perceived public humiliation and belittlement during clinical teaching as detrimental to the well-being of students and the overall learning environment. For example, according to one study,56 as many as three fourths of students who had experienced mistreatment, particularly verbal abuse and unfair tactics, reported having become more cynical about the academic life and the medical profession as a result of these episodes. Furthermore, two thirds felt they were worse off than their peers in other professions and more than a third considered dropping out of medical school.

In addition, Richman et al57 found that mistreatment correlates with poor emotional and mental health outcomes such as drinking problems, decreased self-confidence and self-esteem, and depression. Heru and Gagne58 found that, over time, mistreatment led to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. In the same vein, two out of every three medical students who had experienced this behavior in the current research stated that it had adverse effects on them at a personal and/or educational levels. It is therefore arguable that there is a great incentive for change and improvement in bedside teaching encounters.

In a study, Dyrbye et al59 found that less than a third of victims of mistreatment in medical school reported the incidence. In a way, student responses about reasons for not reporting in the present study were not surprising: they confirm multiple prior reports about mistreatment from other medical schools.20,21 What is perhaps most disturbing about the students’ responses is that, with a few exceptions, they did not believe that they could report abuse to persons of authority. Only one student responded reporting to faculty or official staff in the college, majority reported to fellow students. This finding raises important question about the current administrative intervention efforts. Inappropriate intervention processes may foster a culture of silence. It may be that students’ reporting patterns have evolved over the years to the current situation; nonetheless, there is an ongoing obligation to reexamine the current approach.

In addition, the current study illustrates paradoxes created by student mistreatment in medical colleges and is consistent with other studies of dominance and resistance.60 These data revealed that students who are mistreated are faced with a dilemma. If they work to resist mistreatment by reporting to authority, they are placing themselves in a position where they are likely to face more mistreatment. If they react to the mistreatment by deciding to be silent and keep up with, they are indirectly recreating the power structures and giving up on the chance of being heard. By protecting themselves, they contribute to the processes of devoicing for both themselves and others as they keep discussion about mistreatment out of the administrative and public realm.

They said we can report. Report a teacher that will eventually examine you for promotion? Complain to whom? Students are at the bottom of the ladder in this profession so we get used to it. [Student quote]

Various studies in related organizations have shown that mistreatment is in several ways related to the power position of the instigator. First, it is common for the instigator to be found higher up in the organizational hierarchy.61 Based on the social power theory, French and Raven62 and Cortina et al63 argue that mistreatment can serve as a means of exercising power. In addition, another study64 revealed that individuals experienced rude treatment in a more negative way if it was initiated by someone who had a higher position. In light of the possible relationship between mistreatment and power position, it is relevant to acknowledge and examine power relationships and the positive and negative uses of power by members of the hierarchy for the purpose of understanding the internal structures of the practice of medicine that can lead to student mistreatment.35

Forbidding verbal abuse during bedside teaching encounters as the current intervention strategy indicates that it is not a satisfactory method of intervention. Such an approach tends to extract medical teachers’ behaviors from the context of daily practice or focus on only formal learning activities taking place during clinical training. Bedside teaching, similar to other work-based learning, in contrast, is made up of on the job dynamics and contextually bound activities.65 If this is not recognized, unreasonable expectations may be placed on individuals to effect change, without attending to social structures within which they operate.

It all boils down to everything, I mean the teachers, nurses, residents and other staff, all professional groups on different occasions exhibit this behaviour and am developing thick skin. For example, some nurses feel superior, when a student cannot perform a procedure and humiliated by attending consultant. [Student quote]

A sociocultural perspective on work-based learning offers an approach that locates bedside teaching and learning within social activities, taking place in the interactions between people (clinical teachers, students, nurses, ward staff, and patients), between people and artifacts (stethoscopes, white coats, and students notes), and in interaction with specific physical and social contexts.52 In line with this, Rees and Monrouxe66 highlighted the dynamic interplay between individuals and the environment by proposing four factors that contribute to an abusive culture in medical workplace – the perpetrators, the organization (medical school climate), the nature of the work, and the victim. Yet most intervention efforts to prevent public humiliation of students during clinical training grossly underestimate the influence of institutional forces and cultural pressures that can lead to or promote this behavior. Acknowledgment of these interactions has implications for “toxic” practice intervention strategy.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The researcher’s dual identity as a medical educator and a researcher undertaking a study in a medical college can be seen as both a limitation and a strength. Understandably, the researcher’s medical background could make it difficult to appreciate how strange or troubling certain practices might be to those unfamiliar with the medical education setting. Also, students’ self-reported responses might have been influenced by their assumptions about the researcher’s attitudes, based on professional background. However, the fact that the researcher is a clinical teacher might have facilitated opportunity to collect rich data from the students in a clinical environment.

Conclusion, recommendations, and direction for research

The current research study provided valuable insights into the prevalence and nature of “toxic” practice in a medical college in Nigeria. Why is it that majority of student mistreatment experiences are not officially reported? Are we overlooking some important aspects of “toxic” practice in our current intervention strategy that require further elucidation in order to address the problem?

The underlying current intervention approach is a one-dimensional static view of teaching and learning, and clinical training of medical students is being viewed as an independent variable within the medical education program that produces an effect on the learner.36 One main challenge with this perspective is that it pays little attention toward understanding possible work groups and workplace climates that enable, reward, or perpetuate mistreatment. Furthermore, this approach tends to extract medical teachers’ behaviors from the context of daily practice or focus on only formal learning activities taking place during clinical training.

The recommendations below are intended to address the issues identified in this study with particular attention to the ways that the current education system needs to be changed in order to minimize or prevent student mistreatment.

Recommendations for pedagogy and curriculum

Over the past several years, there have been significant changes in pedagogic techniques. The exploration of adult learning theories offers suggestions as to how questions during bedside teaching encounters might be more useful to the medical students. For example, the learning environment is noted to be as much as important as the knowledge obtained within it.5 The learning environment needs to be safe, respected, and supported during the question-and-answer sessions. Bedside teaching that ensures a proper balance between belittling the learner who gives incorrect answers and boring the group learners by teachers simply providing the answers is a true pedagogical skill.23 The researcher suggests faculty development programs for clinical teachers to master this skill accordingly. It is argued unequivocally that “toxic” practice, by its definition, must be abandoned.

Recommendations for policy

Although the formal curriculum at this medical college attempts to instill humanism in the students, the hidden curriculum as represented by “toxic” practice can undermine these efforts when faculty does not model the behavior taught to students in the classroom. The researcher is of the opinion that this medical college is not alone in this challenge. It is the responsibility of the institution to take the lead and change the policy to effect change in this local culture. Exposing a hidden curriculum that perpetuates a culture of mistreatment is crucial to finding a solution.

Recommendations for further research

Overall, much work needs to be done in addressing medical student mistreatment. A large gap remains between initiatives and interventions, and research regarding the evaluation of these efforts. Future research should focus on improving our understanding of how the interaction of multiple factors related to complex clinical teaching may hamper a change in the culture of mistreatment.

Furthermore, in future studies, it would be important to expand research on medical student mistreatment to developing and evaluating alternative intervention strategies that takes into consideration multiple factors that contribute to “toxic” practice. This may thus improve teacher–student interactions and subsequently “detoxify” bedside teaching encounters.

Acknowledgments

This study is an extract from a research work conducted as part of a practice-based inquiry course work for the award of Postgraduate Certificate in Educational Leadership and Management, University of Nottingham, UK. The researcher is grateful to the students who agreed to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Author contributions

The author conceptualized and developed the idea of study, collected and analyzed the data, prepared and critically revised the manuscript, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kost A, Chen FM. Socrates was not a pimp: changing the paradigm of questioning in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90:20–24. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy C. Pimping in medical education: lacking evidence and under threat. J Am Med Educ. 2015;314:2347–2348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loughran J. Researching teacher education practices: responding to the challenges, demands and expectations of self-study. J Teach Educ. 2007;58(1):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo L, Regehr G. Medical students understanding of directed questioning by their clinical preceptors. Teach Learn Med. 2016;19:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1213169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ende J, Pomerantz A, Erickson F. Preceptors’ strategies for correcting residents in an ambulatory care medicine settings: a qualitative analysis. Acad Med. 1995;70:224–229. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199503000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinholtz D. Directing medical students clinical case presentations. Med Educ. 1983;17:364–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1983.tb01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31(8):685–695. doi: 10.1080/01421590903050374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewson MG. Teaching in the ambulatory setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:76–82. doi: 10.1007/BF02599107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haviland MG, Yamagata H, Werner LS, Zhang K, Dial TH, Sonne JL. Student mistreatment in medical school and planning a career in academic medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:231–237. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2011.586914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maida SAM, Herskovic MV, Pereira SA, Salinas-Fernández L, Esquivel CC. Perception of abuse among medical students of the University of Chile. Rev Med Chil. 2006;134(12):1516–1523. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872006001200004. Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott KM, Caldwell PH, Barnes EH, Barrett J. “Teaching by humiliation” and mistreatment of medical students in clinical rotations: a pilot study. Med J Aust. 2015;203(4):185.e.1–185e.6. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. Br Med J. 2006;333:682–684. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook AF, Arora VM, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):749–754. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peres MF, Babler F, Arakaki JN, et al. Mistreatment in an academic setting and medical students’ perceptions about their course in São Paulo, Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2016;134(2):130–137. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2015.01332210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC) AFMC Graduation Questionnaire National Report 2017. 2017. [Accessed December 27, 2017]. Available from: https://afmc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/en/Publications/2017_GQ_National_Report_en.pdf.

- 16.World Medical Association (WMA) WMA Statement on Bullying and Harassment Within the Profession. Chicago: 2017. [Accessed December 27, 2017]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-statement-on-bullying-and-harassment-within-the-profession/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oku AO, Owoaje OO, Monjok E. Mistreatment among undergraduate medical trainees: a case study of a medical school. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:678–682. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.144377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller E. Humanism in medicine essay context: third place. Acad Med. 2010;85:1628–1629. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f11ce8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmer S, Yousafzai AW, Bhutto N, Alam S, Sarangzai AK, Iqbal A. Bullying of medical students in Pakistan: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maida AM, Vasquez A, Herskovic V, et al. A report on students abuse during medical training. Med Teach. 2003;25:497–501. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001606317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson TJ, Gill DJ, Fitzjohn J, Palmer CL, Mulder RT. The impact on students’ of adverse experiences during medical school. Med Teach. 2006;28:129–135. doi: 10.1080/01421590600607195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owoaje ET, Uvhendu OC, Ige OK. Experience of mistreatment among medical students in a university in south west Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2012;15:214–219. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.97321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaughn L, Baker R. Teaching in the medical setting: balancing teaching styles and teaching methods. Med Teach. 2001;23:610–612. doi: 10.1080/01421590120091000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV, White K, Leibowitz A, Baldwin DC., Jr A pilot study of medical student “abuse”. Student perceptions of mistreatment and misconduct in medical school. J Am Med Assoc. 1990;263:533–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neville AJ. In the age of professionalism, student harassment is alive and well. Med Educ. 2008;42:447–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swanwick T, Morris C. Shifting conceptions of learning in the workplace. Med Educ. 2010;44:538–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haizlip J, May N, Schorling J, Williams A, Plews-Ogan M. Perspective: the negativity bias, medical education, and the culture of academic medicine: why culture change is hard. Acad Med. 2012;87:1205–1209. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628f03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole KA, Barker LR, Koldner K, et al. Faculty development in teaching skills: an intensive longitudinal model. Acad Med. 2004;79:469–480. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leslie K, Baker L, Egan-Lee E, Esdaile M, Reeves S. Advancing faculty development in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;38:1038–1045. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294fd29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Einarsen S. Harassment and bullying at work: a review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggress Violent Behav. 2000;4:371–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, Uijtdehaage S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: a longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad Med. 2012;87:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182625408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogh A, Dofradottir A. Coping with bullying in the workplace. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2001;10:485–495. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, Uijtdehaage S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: a longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad Med. 2012;87:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182625408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutchinson M. Restorative approaches to workplace bullying: educating nurses towards shared responsibility. Contemp Nurse. 2009;32:147–155. doi: 10.5172/conu.32.1-2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angoff NR, Duncan L, Roxas N, Hansen H. Power day: addressing the use and abuse of power in medical training. J Bioeth Inq. 2016;13:203–213. doi: 10.1007/s11673-016-9714-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyon P. A model of teaching and learning in the operating theatre. Med Educ. 2004;33:1278–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begley CM. Using triangulation in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24(1):122–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.15217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. Acad Manage Rev. 1998;14:532–550. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ibrahim M. Medical education in Nigeria. Med Teach. 2007;29:901–905. doi: 10.1080/01421590701832130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olasoji HO. Addressing the issue of faculty development for clinical teachers in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:665–666. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.127576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olasoji HO. Feedback after continuous assessment: an essential of students’ learning in medical education. Niger J Clin Pract. 2016;19:692–694. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.188696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greene JC, Caracelli VJ, Graham WF. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed method education designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1989;11:255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edwards R, Alldred P. Children and young people’s views of social research: the case of research on home-school relations. Childhood. 1999;6:261–281. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flutter J, Rudduck J. Consulting Pupils: What’s in it for Schools? London: Routledge Falmer; 2004. pp. 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leitch RJ, Gardner S, Mitchell L, et al. Consulting pupils in assessment for learning classrooms: the twists and turns of working with students as co-researchers. Educ Action Res. 2007;15:459–478. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract. 1996;13:522–525. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.6.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pedder D, McIntyre D. Pupil consultation: the importance of social capital. Educ Rev. 2006;58:145–157. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomson P, Gunter H. The methodology of students-as-researchers: valuing and using experience and expertise to develop methods. Discourse. 2007;28:327–342. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van der Zwet J, Dorman J, Teunissen PW, de Jonge LPJW, Scherpbier AJJA. Making sense of how physician preceptors interact with medical students: discourses of dialogue, good medical practice, and relationship trajectories. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2014;19:85–98. doi: 10.1007/s10459-013-9465-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measure to achieve trustworthiness. Nurs Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Musselman LJ, MacRae HM, Reznick RK, Lingard LA. “You learn better under the gun”: intimidation and harassment in surgical education. Med Educ. 2005;39:926–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seabrook M. Intimidation in medical education: students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Stud Higher Educ. 2004;29:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keashly L, Neuman J. Faculty experiences with bullying in higher education. Admin Theory Prax. 2010;32:48–70. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richman JA, Flaherty JA, Rospenda KM, Christensen ML. Mental health consequences and correlates of reported medical student abuse. JAMA. 1992;267:692–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heru A, Gagne G, Strong D. Medical student mistreatment results in symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:302–306. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.33.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clinic. 2005;80:1613–1622. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trethewey A. Isn’t it ironic: using irony to explore the contradictions of organizational life. West J Commun. 1999;63:140–167. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Estes B, Wang J. Workplace incivility: impacts on individual and organizational performance. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2008;7:218–240. [Google Scholar]

- 62.French RP, Jr, Raven B. The bases of social power. In: Cartwright D, editor. Studies in Social Power. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1995. pp. 150–167. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cortina LM, Magley VJ, Williams JH, Langhout RD. Incivility at the workplace: incidence and impact. J Occup Health Psychol. 2001;6:64–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cortina LM, Magley VJ. Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. J Occup Health Psychol. 2009;14:272–288. doi: 10.1037/a0014934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meares MM, Oetzel JG, Torres A, Derkacs D, Ginossar T. Employee mistreatment and muted voices in the culturally diverse workplace. J Appl Commun Res. 2004;32:4–27. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. A morning since eight of pure grill: a multischool qualitative study of student abuse. Acad Med. 2011;86:1374–1382. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182303c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]