Abstract

Background: Palliative care (PC) is often misunderstood as exclusively pertaining to end-of-life care, which may be consequential for its delivery. There is little research on how PC is operationalized and delivered to cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials.

Objective: We sought to understand the diverse perspectives of multidisciplinary oncology care providers caring for such patients in a teaching hospital.

Methods: We conducted qualitative semistructured interviews with 19 key informants, including clinical trial principal investigators, oncology fellows, research nurses, inpatient and outpatient nurses, spiritual care providers, and PC fellows. Questions elicited information about the meaning providers assigned to the term “palliative care,” as well as their experiences with the delivery of PC in the clinical trial context. Using grounded theory, a team-based coding method was employed to identify major themes.

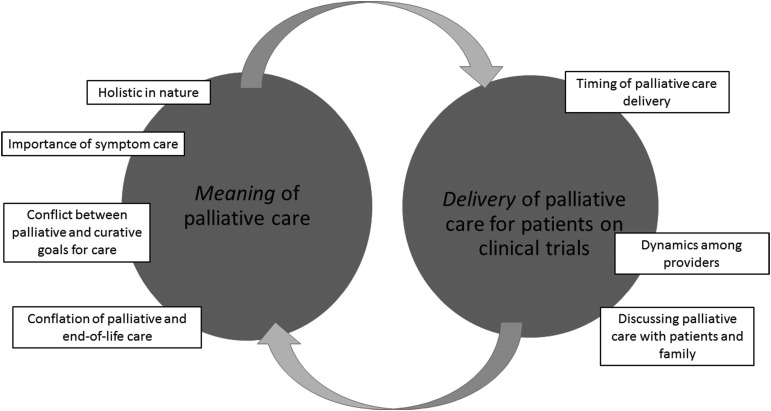

Results: Four main themes emerged regarding the meaning of PC: (1) the holistic nature of PC, (2) the importance of symptom care, (3) conflict between PC and curative care, and (4) conflation between PC and end-of-life care. Three key themes emerged with regard to the delivery of PC: (1) dynamics among providers, (2) discussing PC with patients and family, and (3) the timing of PC delivery.

Conclusion: There was great variability in personal meanings of PC, conflation with hospice/end-of-life care, and appropriateness of PC delivery and timing, particularly within cancer clinical trials. A standard and acceptable model for integrating PC concurrently with treatment in clinical trials is needed.

Keywords: : clinical trials, oncology, palliative care

Background

Palliative care (PC) is considered an important component of patient-centered cancer care; however, debates surrounding a standard definition of PC are ongoing among many professional organizations.1–3 Despite differences, each definition includes a focus on providing relief from symptoms and psychological distress, as well as improving patients' quality of life (QOL) through expert symptom management, spiritual, and psychosocial care.3,4 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends that all patients with advanced cancer or high symptom burden receive a PC consultation within weeks of diagnosis,5 as early initiation of PC has been shown to improve patient satisfaction and QOL.6–9 Barriers to timely initiation and delivery of PC exist at multiple levels, however, particularly for patients enrolled in cancer clinical trials.2,10

Although PC can be delivered at any stage of advanced illness, including concurrently with curative care, it is often misunderstood as exclusively end-of-life care.11 Because of this conflation, providers and patients are often unclear about the appropriate timing and delivery of PC. PC can also be delivered by the oncologist, palliative team, or a combination, and could be contingent on resources available at the place of treatment and insurance coverage, further complicating such initiation. Patients and their caregivers are also often reluctant to discuss care transitions and the use of PC, particularly in the context of clinical trials, feeling that the provider may “give up” on the patient or that PC implies the loss of “hope.”12 Similarly, oncologists report frustration that patients may shift their focus away from “fight” mode if they initiate PC.13

Compounding these barriers are the myriad—sometimes incongruent—terms used interchangeably with PC, including “supportive care,” “symptom management,” and even “hospice care.”4 Although the term PC is widely used, it is unclear how both researchers and clinical providers conceptualize and operationalize it, particularly in cancer clinical trials. Although evidence demonstrating the benefits of PC for cancer patients grows,3,6,7 few studies have explored its concurrent delivery with trial delivered therapy.14 This is an important deficit, given that many patients enrolled in clinical trials may have failed standard treatments, have advanced cancer, experience high symptom burden, and consequently, have potentially life-threatening diagnoses. Furthermore, PC encompasses a multidisciplinary approach,2 and as such, understanding discipline-specific approaches to its delivery is critical. This key-informant study is a first step in understanding how teams of cancer care providers in a clinical trial setting define and operationalize PC.

Methods

This article is part of a larger qualitative study on goals of care in advanced cancer clinical trials at a U.S. teaching hospital (article under review). We purposively sampled members of two multidisciplinary cancer clinical trial teams (N = 19) providing care for patients enrolled in phase I and II clinical trials. Based on access and availability, the two teams cared for hematologic and prostate cancer patients. Key informants from each team were selected to include diverse roles: a principal investigator/attending physician (PI), oncology MD fellow (OF), research nurse (RN), physician's assistant (PA) or nurse practitioner (NP), and social worker (SW) (Table 1). We also interviewed additional care providers and staff who are not explicitly assigned to a research team, including clinical nurses (CNs), palliative care MD fellows (PCFs), a chaplain, and pharmacist. These providers care for patients enrolled in both hematologic and prostate cancer clinical trials. This clinical setting does have a dedicated PC team that can be consulted as needed.

Table 1.

Description of Respondents

| Team 1 | Principal investigator (PI) | Nurse practitioner |

| Oncology MD fellow (OF) | Program administrator | |

| Research nurse (RN) | Social worker (SW) | |

| Team 2 | PI | Physician's asssistant (PA) |

| OF | Patient care coordinator | |

| RN | SW | |

| Additional healthcare providers and staff | Clinical nurse (CN)-outpatient (2) | Spiritual care (chaplain) |

| CN-inpatient | Pharmacist | |

| Palliative care fellow (2) |

PIs of each team nominated team members to be approached to participate in the study. We conducted in-person (n = 17) and telephone (n = 2) semistructured interviews. As part of the interview, participants were asked the following questions: (1) “What does PC mean to you in your current role?” and (2) “What is the process for initiating and delivering PC for your patients?” Interviews were recorded and transcribed; all identifying information was redacted. This study was deemed exempt from institutional review.

Using the qualitative methodology of grounded theory, we used MacQueen's team-based coding methodology to identify emerging themes.15,16 In brief, a preliminary codebook was developed through an iterative and data-driven discussion after each author had a chance to review the transcripts and identify candidate codes. The codebook was then revised and all team members pilot-tested two randomly selected transcripts, each of which was double coded. After resolving discrepancies across coders and reaching team consensus, a final codebook was used to analyze all 19 transcripts with NVivo coding software version 10.

Results

Seven major themes suggest diverse conceptualizations of PC and illustrate the complex relationship between its definition and actual delivery, as illustrated in Figure 1. Themes and example quotes are presented hereunder.

FIG. 1.

Seven major themes suggest diverse conceptualizations of palliative care and illustrate the complex relationship between its definition and actual delivery.

Meaning of PC

Four major themes emerged regarding the meaning of PC, including (1) holistic nature of PC, (2) importance of symptom care, (3) conflict between PC and curative goals of care, and (4) conflation between PC and hospice/end-of-life care.

Holistic nature of PC

Participants felt that PC is holistic and aimed at caring for the whole patient. Respondents emphasized that PC encompasses supportive services, including counseling, spiritual care, acupuncture, and massage therapy.

“Making sure that they have access to all the resources…such as pain and palliative care services, spiritual services.” (Pharmacist)

This holistic orientation to care also included a keen awareness of patients' values, including attention to QOL. Respondents stressed the importance of listening to patients to determine their needs.

“It's coming to know what are your values, your goals, what makes life meaningful for you, and how do we manage your trajectory through this illness experience in a way that maximizes your ability to be at peace and feel that your life has meaning.” (Chaplain)

Importance of symptom care

Symptom management was central to several respondents' understanding of PC. Providers, and particularly those involved in direct patient care (e.g., PA, RN, pharmacist, and OF), noted the importance of addressing symptoms, with particular attention to pain management.

“Our intent of giving palliative care is…when the symptoms are to the point where they can't be managed by just routine time constraints and routine treatments, we need extra attention to the patient's symptoms.” (OF)

Although pain relief was often referenced, two respondents noted that PC can also include chemotherapy to slow tumor progression and alleviate further symptoms. Respondents also mentioned management of psychosocial symptoms (e.g., distress and anxiety) as a key component of PC, including psychotherapy, caregiver support, and spiritual care.

Conflict between PC and curative goals of care

Respondents noted discordance between curative and palliative goals of care. Two shared that, in their experience, PC is not incorporated into clinical trials.

“We don't do it [palliative care]. That was my first thought.” (CN)

“I honestly haven't used palliative care much at all.” (NP)

Perhaps unique to a clinical trials context, respondents also expressed conflict between goals of PC and research goals, pointing to widespread tensions across roles and responsibilities.

“There has been some resistance from the [team] to use palliative care.” (OF)

Respondents also mentioned that initiating PC could be interpreted as “giving up” on the patient and something that would only be appropriate at the end of life.

“Sometimes, people will say…‘The death team’…that it means comfort measures only, end-of-life…it can be stigmatized a little bit where people actually think we're coming there to expedite people's death.” (PCF)

“A lot of the outside healthcare world puts labels on it…a 6-month [to live] diagnosis [before palliation is offered].” (CN)

These excerpts make the direct connection between PC, poor prognosis, and imminent death. Respondents did recognize a stigma surrounding PC, in that some consider it to be only appropriate for end-of-life patients and believe it to be at odds with active treatment.

Conflation of palliative and hospice/end-of-life care

Responses suggested a conflation between PC and hospice/end-of-life care. Although most respondents began by describing PC as “more than just end-of-life care,” five respondents focused solely on the latter. Other respondents used the terms interchangeably or alternated between them.

“When I think of palliative care, I'm thinking end-of-life hospice, the patient will pass.” (CN)

“Palliative care is either a blank slate or an emotionally charged issue. Or hospice is, I guess. What are we talking about…?”(PI)

Here, it is possible that the PI's view and conflation of hospice and PC might set the tone for the team. Five respondents noted a clear distinction between PC and hospice/end-of-life care, but clarified that the terms are viewed by many as synonymous.

“I think of palliative as…a cloak. I think of hospice or end-of-life as like a small patch on the cloak…a lot of people focus on the patch, like, ‘Oh, they're only end-of-life for hospice,’” (PCF)

This response illustrates that although hospice is an important component of PC, it is only one part of a much more complex concept.

Delivery of PC

Responses to PC delivery probes clustered around three main themes, including (1) dynamics among providers, (2) discussing PC with patients and family, and (3) timing of PC delivery.

Dynamics among providers

Our analysis revealed complex dynamics regarding who is responsible for initiating, delivering, and coordinating PC. Respondents shared challenges in determining who is responsible for PC processes, and opinions varied among teams. Some PIs and OFs felt that their team could handle all PC needs without consulting the PC team, whereas others reported regularly reaching out to the palliative team for support in patient care.

“There has been some resistance… We like to handle everything on our own.” (OF)

“There's a lot of negotiation, striking an agreement with the team…” (CN)

Respondents, including a CN, SW, and PCF, indicated that communicating with PIs can be difficult and often involves hierarchical tension and substantial negotiation.

“You're trying to tell the primary team…a patient said that they want to change their plan…decrease their care, but the primary team is not ready to hear that, yet, or they're not wanting to hear that, yet, because they had high hopes or plans for other things.” (PCF)

CNs generally felt it was the role of the PIs or OFs to initiate PC or order a palliative team consultation, but expressed comfort with the important role they play in supporting decision making.

“I usually report it to the team caring for the patient and then they communicate with the PI if needed… the best thing to do is get the PI down here to talk to the patients… and that has helped immensely.” (CN)

Discussing PC with patients and family

Six respondents stressed that the PI usually initiates PC conversations with patients, which was confirmed by the PIs and OFs. It was evident, however, that discussing PC with patients and their family is challenging.

“We might say, ‘Hey, patient's concerned, the family members are concerned.’ …patients don't want to say something…in front of a whole group of doctors…Especially if you're on a research trial.” (RN)

“The communication breakdown can be when patients, maybe, aren't ready to hear things or wanting to hear certain things…” (PCF)

Timing of PC delivery

Timing of PC initiation and delivery was an issue complicated by apparent conflict between clinical trial and palliation goals. Five respondents said that PC was initiated when symptom management became difficult or complex, particularly when pain was unmanageable.

“I think anytime the patient is starting to have pain, it's something that gets our antenna up.” (RN)

One PCF did indicate that the optimal time to initiate PC is at the first visit. Although the following quote may refer to patients with advanced cancer, the response suggests that a relationship where research and palliative teams collaborate may be the most effective.

“There are some diagnoses where I should be called the day they come in. We'll partner together…that's such a privilege (for me).” (PCF)

Providers in several roles (PIs, OFs, PCFs, and CNs) noted that PC was often delayed. This issue was further complicated by the perceived conflict between curative and palliative goals of care, particularly in the context of patients enrolled on clinical trials.

“Sometimes we end up waiting longer than we should… We've done that many times.” (OF)

“There's a lag sometimes I've noticed, unfortunately, in when nurses think patients have had enough and sometimes what PIs have thought.” (CN)

Discussion

This study sought to examine how multidisciplinary care providers understand and deliver PC to patients participating in cancer clinical trials. In this context, patients often have advanced cancer and a potentially terminal diagnosis, making timely and effective delivery of PC particularly important. In addition to the diverse range of operational definitions of PC, the complexity and confusion surrounding the meaning of PC appeared to influence if, how, and when PC is delivered.

Extending prior research,17 our study demonstrates perceived conflict between curative and palliative goals among providers, possibly amplified by the research setting of this study. Clinical trials often enroll patients whose status can worsen during the trial, many of whom could benefit from optimal delivery of PC. PIs have the primary responsibility for systematically identifying, documenting, and reporting adverse events for those enrolled in clinical trials,18 and for appropriately incorporating the early integration of PC. Indeed, recent updates to the ASCO PC recommendations note the benefit of integrating PC concurrently with cancer clinical trials.3 Facilitating patient-centered cancer care requires the acknowledgment of the dynamic values and preferences of cancer patients. This includes presenting research, curative, and palliative goals as complementary rather than conflicting. In fact, some clinicians have called for PC to be viewed as complementary to oncologic care, particularly at the following stages: (1) management of symptoms due to cancer and/or its therapy, (2) management of pain or chronic complications and provision of psychosocial support once oncologic therapy is no longer curative, and (3) holistic care at the end of life.19

Our research suggests great variability in how multidisciplinary providers conceptualize and deliver PC, which is further complicated by the apparent conflation between PC and hospice or end-of-life care. To alleviate tensions between team members focused on treatment for extending life versus those focused on palliation, a shared definition of PC is necessary. Some organizations have considered using the term “supportive” rather than “palliative” care, as this term may carry fewer associations with end of life.4,20 Research indicates several themes of supportive care that clearly overlap with PC, including a focus on symptom management, QOL, and meeting the holistic needs of the patient.20,21 In fact, a retrospective study of >4,700 cancer patients found that changing the terminology from “palliative” to “supportive” care resulted in earlier inpatient and outpatient PC referrals.22 Future research should examine whether rebranding PC as supportive care increases its acceptability and implementation among providers in addition to patients—particularly within the context of clinical trials.

Even with a shared definition, our study demonstrates possible discordance between providers with regard to the operationalization and delivery of PC. The setting of our study included access to the PC team for both inpatient and outpatient clinical trial enrollees. This could have contributed to the variability of our findings in terms of who is responsible for initiating and delivering PC. Many oncology practices employ primary PC by providing palliation themselves until symptoms become unmanageable and a PC specialty consult is deemed necessary. Knowing when to contact PC specialists is both difficult and critically important. To this end, the adoption of standardized models for the integration of PC across cancer sites is urgently needed.23,24 Such models outline who should receive a PC referral and when, the roles and responsibilities of respective providers, and suggested settings for PC delivery. Examples include (1) the time-based model, where PC is offered at a standard time in the disease trajectory; (2) the provider-based model, where provision of PC is dependent on the level of patient complexity and the setting; (3) the issue-based model, where PC is initiated only when the oncologist is unable to address all of the patient's concerns; and (4) the system-based model, where PC delivery is standard and not dependent on oncologist preference.23 Although these models have shown promise in enhancing PC delivery,23 they are only now being preliminarily tested in the context of clinical trials.14,25 The adoption of PC integration in cancer care can also be informed by models being used in other diseases, such as heart failure, where evidence and guidance are also emerging.26 Our findings also suggest that the conflation of PC and hospice/end-of-life care may affect the timing of PC delivery. As such, future research is needed to promote and improve patient-centered care in the context of clinical trials, including the systematic integration of PC.

Our findings should be interpreted with certain limitations in mind. First, the study was conducted at a teaching facility within a clinical trials context, and results may not generalize to community settings and organizations without a dedicated PC service. In addition, although our attempt to elucidate intra- and interteam differences in understanding and conceptualizing PC could be seen as a strength in that we attempted to obtain a diverse set of provider perspectives, we interviewed only two clinical trial teams and their staff and, as such, these results may not reflect the experiences of teams providing care for other types of trial patients. We also utilized a snowball sampling technique, where the PI of each team nominated team members to participate, thereby introducing the potential for bias. Finally, because we rely on provider self-report, it is possible that responses provided for this study differ from actual practice.

Conclusions

This study identified barriers to implementing PC for patients enrolled in cancer clinical trials, including the lack of shared understanding of PC, conflation of PC with end-of-life care, and lack of clarity in the delivery process. Although our findings have highlighted that misconceptions surrounding PC can limit its use, integrating it more systematically into clinical trial care delivery could promote patient-centered care and improve QOL. As clinical trials remain a backbone of scientific discovery for the advancement of cancer diagnosis and treatment, it is imperative to support patients by appropriately integrating palliative services into their care regardless of curative or research goals.

Author Disclosure Statement

No authors have declared a conflict of interest. The senior author (W.C.) has full control of all primary data and we agree to allow the journal to review data if requested.

References

- 1.Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC): MASCC Palliative Care Study Group. 2016; www.mascc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=187:palliative-care&catid=25:study-groups (last accessed December1, 2017)

- 2.World Health Organization: WHO definition of palliative care. 2002; www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (last accessed December1, 2017)

- 3.Ferrell B, Temel J, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. : Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:659–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borneman T, Ferrell B, Puchalski CM: Evaluation of the FICA Tool for spiritual assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greer J, Jackson V, Meier D, et al. : Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:349–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel J, Greer J, Muzlkansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakitas M, Tosteson T, Li Z, et al. : Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. : Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoeitic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc 2016;316:2094–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MP, Strasser F, Cherny N: How well is palliative care integrated into cancer care? A MASCC, ESMO, and EAPC Project. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:2677–2685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center to Advance Palliative Care: About palliative care. 2016; www.capc.org/about/palliative-care/ (last accessed November1, 2017)

- 12.Broom A, Kirby E, Good P, et al. : The art of letting go: Referral to palliative care and its discontents. Soc Sci Med 2013;78:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakitas M, Doyle Lyons K, Hegel M, et al. : Oncologists' perspectives on concurrent palliative care in an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:415–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrell BR, Paterson CL, Hughes MT, et al. : Characteristics of participants enrolled onto a randomized controlled trial of palliative care for patients on Phase I studies. J Palliat Med 2017;20:1338–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser BG, Strauss AL, eds.: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, 4th ed Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, et al. : Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultur Anthropol Methods 1998;10:31–36 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hui D, Kim Y, Park J, et al. : Integration of oncology and palliative care: A systematic review. Oncologist 2015;20:77–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute (NCI): NCI Guidelines for Investigators: Adverse Event Reporting Requirements. Rockville, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klastersky J, Libert I, Michel B, et al. : Supportive/palliative care in cancer patients: Quo vadis? Support Care Cancer 2016;24:1883–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui D: Definition of supportive care: Does the semantic matter?. Curr Opin Oncol 2014;26:372–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivers D, August E, Sehovic I, et al. : A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans' participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;2013:13–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. : Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 2011;16:105–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui D, Bruera E: Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruera E, Hui D: Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1261–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun V, Cooke L, Chung V, et al. : Feasibility of a palliative care intervention for cancer patients in Phase I clinical trials. J Palliat Med 2014;17:1365–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewin W, Schaefer K: Integrating palliative care into routine care of patients with heart failure: Models for clinical collaboration. Heart Fail Rev 2017;22:517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]