Vickers (1) offers little substantive criticism, but we address three items he mentions: (i) our choice of clinical endpoint, (ii) the potential for multiple-testing false positives, and (iii) the need for additional study.

An important distinction of our study (2) is the use of neovascular AMD (nvAMD) as the endpoint. In 2001, the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) showed that nutritional supplements reduce progression to overall advanced AMD. This main effect was due to reduced progression to nvAMD, with no impact on progression to the geographic atrophy (GA) form of advanced AMD (3). As Vickers notes (1), Seddon et al. (4) confirmed this pharmacogenetic interaction. However, he misquotes or misunderstands Seddon’s conclusion, who states that “similar results were seen for NV subtype but not GA” (4).

Vickers notes that work by Awh et al. (5), an underpowered analysis by Chew et al. (6), and his own cited work (7) report progression to overall advanced AMD. However, the papers of Awh et al. (5) and Chew et al. (6) predated that of Seddon et al. (4), while our paper, and that of Vickers, were published later and should be taking into account findings of Seddon et al. (4).

Awh et al. (5), using overall advanced AMD as an endpoint, first identified the high complement factor H (CFH) and low age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2 (ARMS2) genotype groups (GTGs) tested in our analysis, but in a much smaller dataset. Our study of the largest cohort of AREDS patients to date is based upon data disclosed in Vickers’ analysis, plus 103 patients from the Michigan, Mayo, AREDS, Pennsylvania cohort. Our analysis shows an undeniable interaction of genetics and treatment. We used an accepted statistical approach (0.632 bootstrap) to emulate prospective analysis of combined effects of genetics and treatment on nvAMD progression to demonstrate a strong, statistically significant dependence of treatment outcome on genetics (2).

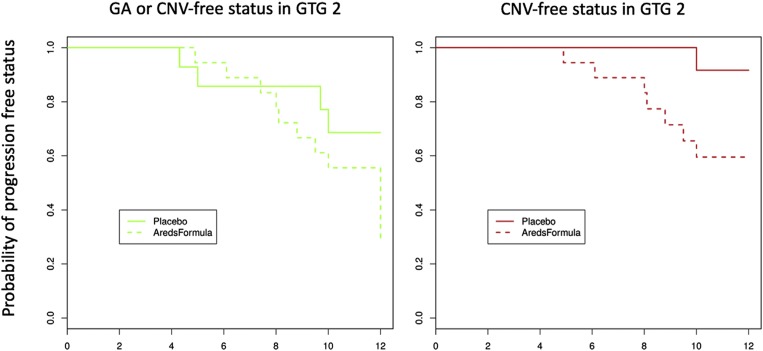

Vickers, using the endpoint of overall advanced AMD, was “unable to replicate any genotype–treatment interactions.” However, when his dataset, which is a subset of our larger dataset, is analyzed using the endpoint of nvAMD, the outcome is dramatically different, as shown in Fig. 1. Patients with high CFH and low ARMS2 risk (GTG2) have increased risk of nvAMD with AREDS treatment [hazard ratio (HR = 6.4, P = 0.015)]. Including GA as an endpoint eliminates statistical significance (HR = 1.04, P = 0.94).

Fig. 1.

Cox proportional hazard estimate of the proportion of GTG2 individuals remaining free of GA or neovascular disease (Left) or just neovascular disease (Right) using the 535-patient validation set of Assel et al. (7). New patient data provided by the NIH in conjunction with the work by Assel et al. (7), which underscores the distinction between GA and choroidal neovascularization (CNV) as distinct progression phenotypes, validate previous observations. The GA endpoint is not relevant for AREDS prophylaxis and should be removed from the statistical analyses. Some patients benefit (GTG3), and some may be harmed (GTG2). Reproduced with permission from ref. 8.

We also validated the GTGs in 299 subjects who had not been part of the analysis of Awh et al. (5). The outcomes were more powerfully demonstrated in this validation dataset than in the primary dataset. Validation in a population not used for model development addresses the concern of overfitted data.

AREDS treatment recommendations are based on a single randomized trial that would take many years and millions of dollars to replicate. For now, we show that the response to AREDS treatment is influenced by CFH and ARMS2 genetic risk, with dramatically different outcomes. Most benefit, but some are harmed. Our study resolves prior competing points of view and provides a template for reasonable patient management. As with many scientific discoveries, this is, to use Vickers’ description, “an important incremental advance.”

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: B.W.Z. is an officer of ArcticDx, which holds patents relevant to results. C.A. and R.K. are technical consultants of ArcticDx.

References

- 1.Vickers AJ. Pharmacogenomics of antioxidant supplementation to prevent age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E5639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803536115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vavvas DG, et al. CFH and ARMS2 genetic risk determines progression to neovascular age-related macular degeneration after antioxidant and zinc supplementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E696–E704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718059115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seddon JM, Silver RE, Rosner B. Response to AREDS supplements according to genetic factors: Survival analysis approach using the eye as the unit of analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:1731–1737. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awh CC, Hawken S, Zanke BW. Treatment response to antioxidants and zinc based on CFH and ARMS2 genetic risk allele number in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chew EY, et al. Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group No clinically significant association between CFH and ARMS2 genotypes and response to nutritional supplements: AREDS report number 38. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2173–2180. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assel MJ, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of CFH and ARMS2 do not predict response to antioxidants and zinc in patients with age-related macular degeneration: Independent statistical evaluations of data from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zanke B. Re: Assel et al.: Genetic polymorphisms of CFH and ARMS2 do not predict response to antioxidants and zinc in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:e34–e35. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]