Significance

Enhancers are regulatory regions in DNA that govern gene expression and orchestrate cellular phenotype. We describe the enhancer landscape of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), identifying established and unique GIST-associated genes that characterize this neoplasm. Focusing on transcriptional regulators, we identify a core group of transcription factors underlying GIST biology. Two transcription factors, BARX1 and HAND1, have mutually exclusive enhancers and expression in localized and metastatic GIST, respectively. HAND1 is necessary to sustain GIST proliferation and KIT expression, and binds to enhancers of GIST-associated genes. The relative expression of BARX1 and HAND1 is predictive of clinical behavior in GIST patients. These results expand our understanding of gene regulation in this disease and identify biomarkers that may be helpful in diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: sarcoma, GIST, epigenetics, transcription factor

Abstract

Activating mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA receptor tyrosine kinases are hallmarks of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). The biological underpinnings of recurrence following resection or disease progression beyond kinase mutation are poorly understood. Utilizing chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing of tumor samples and cell lines, we describe the enhancer landscape of GIST, highlighting genes that reinforce and extend our understanding of these neoplasms. A group of core transcription factors can be distinguished from others unique to localized and metastatic disease. The transcription factor HAND1 emerges in metastatic disease, binds to established GIST-associated enhancers, and facilitates GIST cell proliferation and KIT gene expression. The pattern of transcription factor expression in primary tumors is predictive of metastasis-free survival in GIST patients. These results provide insight into the enhancer landscape and transcription factor network underlying GIST, and define a unique strategy for predicting clinical behavior of this disease.

Sarcomas are heterogeneous malignancies of mesenchymal tissues that account for ∼20% of pediatric and 1% of adult cancers (1). Discoveries to date have identified oncogenic mutations or translocations amenable to targeted therapies in only a few subtypes of sarcoma. The best-characterized is gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), in which KIT- or PDGFRA-activating mutations commonly drive tumorigenesis, and inhibition of signaling through these receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) can lead to disease control (2). For localized disease amenable to surgical resection, the decision to administer adjuvant therapy is based upon the risk of recurrence, which is currently predicted by tumor size, location, and mitotic rate (3). Beyond RTK mutations, the neoplastic programs responsible for recurrence and disease progression are poorly understood. There is urgent clinical need for biomarkers to better predict the risk of recurrence and guide adjuvant therapy decisions.

cis-regulatory elements (CREs) are regions of noncoding DNA which govern transcriptional activity at target genes by coordinating transcription factors (TFs), coactivators such as BRD4, and chromatin regulators. Enhancers are CREs that promote the expression of a target gene, and large enhancer regions called superenhancers (SEs) play essential roles in driving the activity of key genes important for cellular function (4). Compared with typical enhancers (TEs), SEs can be defined by broader regions of contiguous H3K27ac chromatin modification, which marks active chromatin and facilitates binding of transcriptional regulatory proteins (5). The network of enhancers and their resulting transcriptional output are crucial to a cell’s identity (6), and cancer cells acquire and depend upon SE elements at oncogenes (5, 7, 8). Cancer cells may depend on an existing lineage-specific SE or generate new oncogenic SEs (9, 10). Understanding the SE landscape is helpful in determining the core network of cancer subtype-specific genes (11) and in discovering approaches to targeted cellular manipulation as cancer therapy (12). To date, there have been few coordinated efforts to characterize CREs in sarcomas, and investigations of the transcriptional program driving GIST have concentrated on ETV1 (13, 14).

To characterize the CREs regulating GIST oncogenesis, H3K27ac chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing (ChIP-seq) was performed in 12 primary GIST tumor samples and 9 GIST cell lines. We found similarity in the enhancer landscape between KIT- and PDGFRA-mutant GIST tumors, with a conserved RTK-dependent program in GIST cell lines. Informed by SE analysis, we identified a group of regulatory TFs controlling the GIST transcriptional program and accessory TFs unique to different disease states. The TF HAND1 was up-regulated in metastatic GIST and found to bind enhancers of GIST-associated genes, and facilitates KIT gene expression and cellular proliferation. In contrast, the TF BARX1 was exclusive to localized GIST. The relative expression of these accessory TFs was predictive of metastasis-free survival in patients with surgically resected primary GIST. These results define the enhancer landscape in GIST, describe the underlying TF network responsible for gene expression, and identify TFs that influence and predict clinical behavior of this disease.

Results

The GIST Enhancer Landscape.

Our group and others have previously reported the use of H3K27ac ChIP-seq to define cancer-specific enhancer landscapes (11, 15, 16). These studies have revealed tumor dependencies, implicated neoplastic cellular origins, and identified translational approaches to improving cancer diagnosis and therapy. To apply this analytic platform to GIST, we performed H3K27ac ChIP-seq on 12 fresh-frozen primary GIST tumors and 9 KIT-mutant GIST cell lines (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Dataset S4). The primary samples included three metastatic and three localized KIT-mutant tumors, four localized PDGFRA-mutant tumors, and two localized SDHC-mutant GIST tumors. The GIST cell lines consisted of six driven by activating KIT mutations, two of which were subclones containing KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistance mutations, and three cell lines which harbor activating genomic KIT mutations but express KIT at low levels and do not rely on KIT expression or signaling for growth. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of H3K27ac signal at SEs revealed global similarity between GIST tumor samples, regardless of KIT or PDGFRA mutational status, with KIT-dependent cell lines showing a higher degree of similarity to GIST tumors than to KIT-independent cell lines (Fig. 1A). The KIT-dependent GIST cell lines, which were all derived from metastatic GIST tumors, clustered nearest to the metastatic tumors. Comparisons between PDGFRA-mutant GIST and localized or metastatic KIT-mutant GIST revealed more similarities than differences across the enhancer landscape (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), which correlates with previously published gene expression data highlighting the overall homogeneity between these tumor subtypes (17, 18). The KIT-mutant melanoma cell line MaMel had a low degree of similarity with any GIST sample, despite similar dependency on oncogenic KIT signal transduction. KIT-independent GIST cell lines clustered more closely with human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), suggesting the achievement of a dedifferentiated state when escaping KIT dependency.

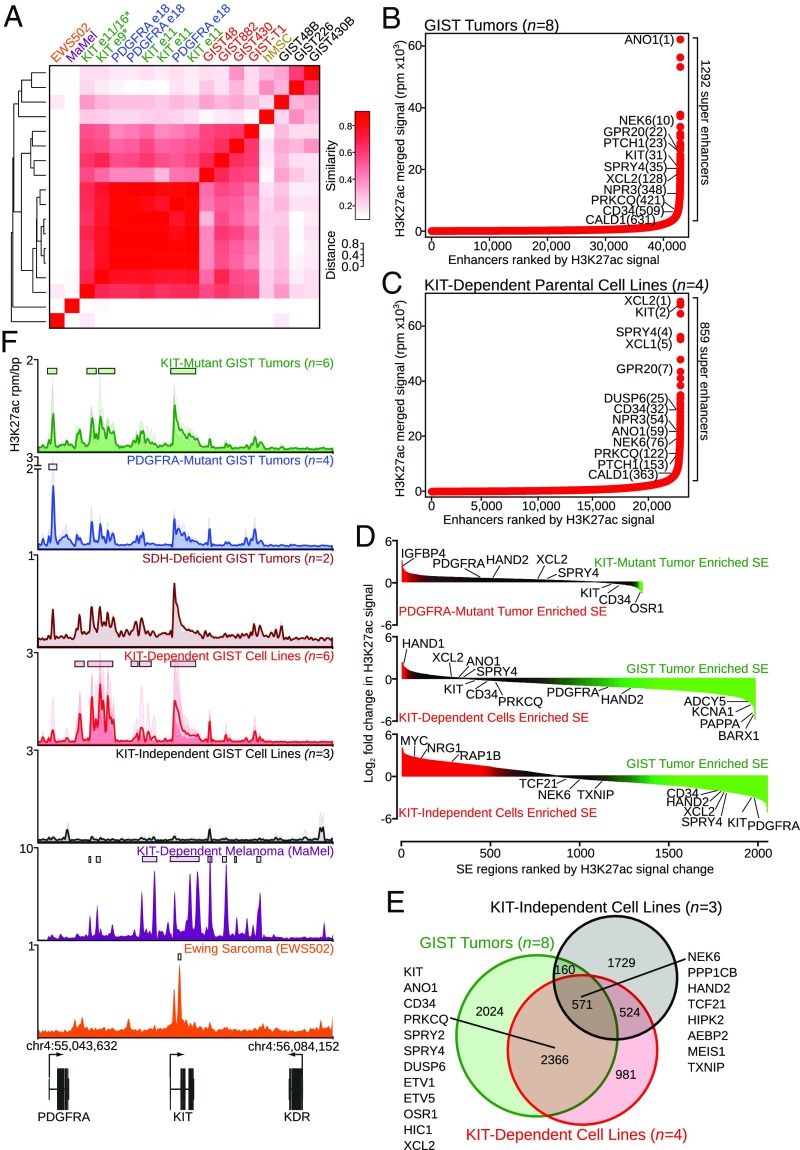

Fig. 1.

Enhancer profiling identifies a conserved GIST program. (A) Heatmap clustering of SEs across tumor samples and cell lines, as defined by H3K27ac ChIP-seq. Sample names are color-coded to indicate tumors (KIT-mutant in green; PDGFRA-mutant in blue; metastatic samples are designated with an asterisk) and cell lines (KIT-dependent in red; KIT-independent in black). Additional comparators include a Ewing sarcoma cell line expressing wild-type KIT (EWS502), a KIT-mutant melanoma cell line (MaMel), and hMSCs. (B and C) Ranked enhancer plots in GIST tumors (n = 8) (B) and KIT-dependent parental cell lines (n = 4) (C). (D) Waterfall plots comparing log2 fold change of SE regions between localized KIT- and PDGFRA-mutant tumors (n = 3 each) (Top), KIT-dependent cell lines (n = 4) and localized GIST tumors (n = 6) (Middle), and KIT-independent cell lines (n = 3) and localized GIST tumors (n = 6) (Bottom). (E) Venn diagram of enhancer peaks conserved in all subgroup samples comparing GIST tumors and cell lines. (F) H3K27ac meta tracks at the KIT locus in GIST tumors and cell lines, in which tracks from individual samples are translucent and the opaque line represents the average signal across all samples. y-axis heights are variable to emphasize peak morphology. SE regions are indicated with rectangles above the associated peaks.

Ranked enhancer plots of GIST tumors identify many characteristic tumor markers and dependencies in addition to multiple unique GIST-associated genes (Fig. 1B and Dataset S1), which show a recurrent pattern in GIST tumor subtypes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B–E). Ranked enhancer plots of KIT-dependent parental cell lines (Fig. 1C) show preservation of a large subset of tumor-associated SEs, in contrast to KIT-independent cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). H3K27ac ChIP-seq meta tracks for characteristic and unique GIST-associated genes show preservation of chromatin modification in vivo and in vitro (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), with loss of select RTK-associated genes in KIT-independent GIST cell lines.

Consistent with SE association and appropriate gene assignment, a subset of these GIST-associated genes were validated as being expressed at the mRNA and protein level in GIST cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C). SE H3K27ac signal was conserved between PDGFRA- and KIT-mutant tumors, with greater similarity between these tumors and KIT-dependent cell lines compared with KIT-independent cell lines (Fig. 1D).

Enhancer peaks and their corresponding genes conserved across all GIST subgroup samples were compiled, and comparison between groups again yielded greater similarity between GIST tumors and KIT-dependent cell lines compared with KIT-independent cell lines (Fig. 1E). In GIST samples, we found numerous intra- and intergenic enhancer domains at the KIT locus (Fig. 1F). The enhancer pattern was preserved between GIST tumors and KIT-dependent cell lines, and was absent from KIT-independent GIST cell lines that have lost KIT expression. The enhancer domains at the KIT locus drove robust expression of the KIT gene compared with surrounding genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Though ChIP-seq data quality limited genome-wide comparisons, SDH-deficient GIST displayed a similar enhancer pattern at this locus, underscoring its regulation by a similar TF network and suggesting an identical cellular origin.

To compare enhancers at the KIT locus in GIST with other cell lines with known KIT expression, we similarly performed H3K27ac ChIP-seq on the KIT-dependent and KIT-mutant MaMel melanoma cell line and the EWS502 Ewing sarcoma cell line, which expresses wild-type KIT but does not require KIT signaling for survival (Fig. 1F, Bottom). The substantial differences in the KIT enhancer landscape in these two cell types reflect the unique set of TFs utilized to drive gene expression, and underscore a GIST-specific transcriptional repertoire which regulates KIT gene expression. In the MaMel cell line, sequencing of input control chromatin indicates amplification of the KIT locus, in contrast to GIST tumors and cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E) and, despite high levels of protein production, the exon 9 mutant MaMel cell line drove features of KIT signaling less efficiently than a KIT-dependent GIST cell line (SI Appendix, Fig. S3F). Taken together, the use of H3K27ac ChIP-seq enabled the identification of a characteristic GIST enhancer program that revealed a set of distinguishing and unique GIST-associated genes.

The GIST Transcription Factor Network.

Master regulatory TF networks have previously been shown to establish the enhancer landscape and reinforce cellular identity and to be maintained in malignancy (5, 15). This network forms an autoregulatory loop, with master TFs driving transcription of themselves within a core circuit. The core circuit further maintains an extended regulatory circuit, and these transcriptional networks define the cell’s specific enhancer pattern (e.g., Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2) and gene expression program.

Regulatory circuitry can be computationally inferred from SE mapping, relying on H3K27ac ChIP-seq and predicted TF DNA-binding motifs (19). Using this approach, we defined 24 core and extended regulatory circuit TFs in GIST (Materials and Methods, Fig. 2A, and Dataset S2), which highlight ETV1 (13) and unique TFs as central to GIST biology. By motif analysis, most of these TFs are predicted to work within the same autoregulatory network. To identify open chromatin where these TFs may bind in GIST, we utilized the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq), with peaks corresponding to putative TF-binding sites within enhancer domains (20) (Fig. 2B). Many GIST-associated TFs with characterized DNA-binding motifs have predicted binding sites in ATAC peaks within the KIT locus (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C), suggesting their collaborative role in regulating the principal oncogene in GIST.

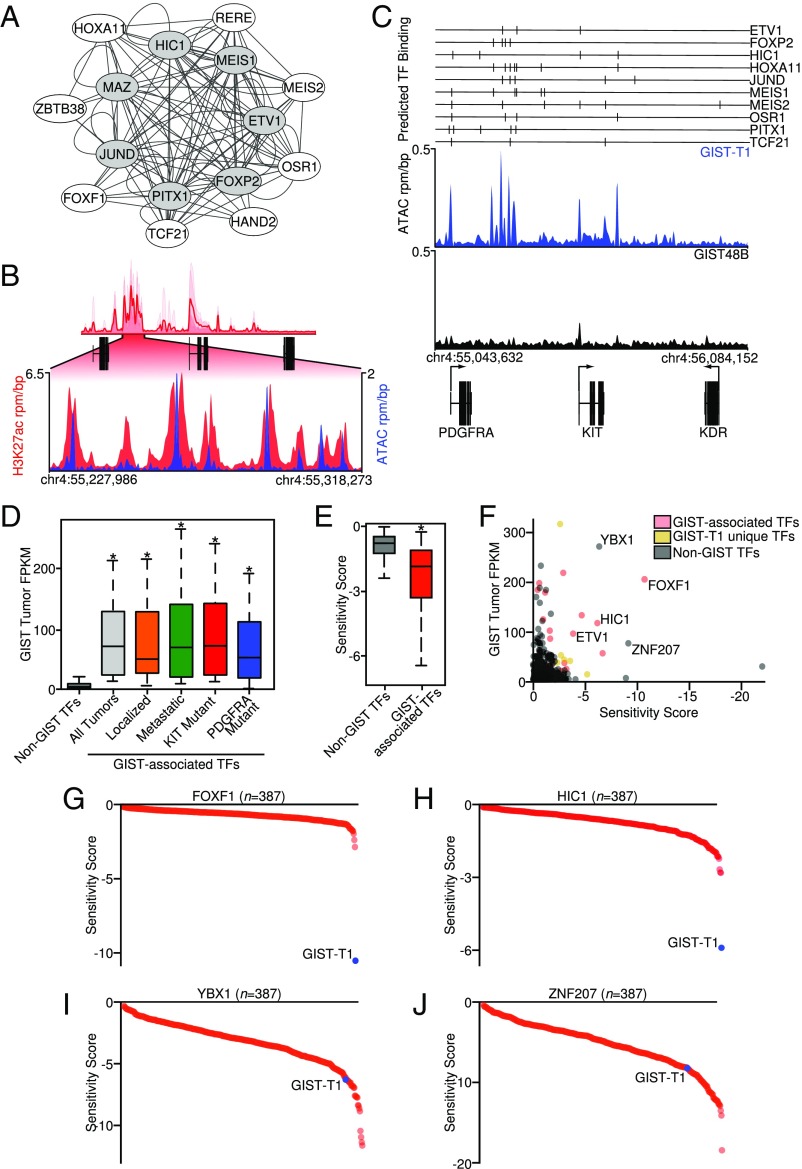

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional regulatory circuitry in GIST. (A) Core (gray) and extended (white) regulatory TF circuitry identified in GIST tumors from core regulatory circuitry analysis. Each GIST-associated TF represents a node in the network, with edges connecting coregulated TFs. (B) Overlap of H3K27ac and ATAC peaks at the KIT SE in the GIST-T1 cell line. (C) ATAC-seq from the KIT-dependent cell line GIST-T1 and the KIT-independent cell line GIST48B at the KIT locus. Predicted binding sites of 10 GIST-associated TFs are indicated with vertical lines. (D) Expression of GIST-associated TFs (n = 24) compared with all other putative TFs (n = 1,410) in all GIST tumors (n = 13) and the disease subtypes including localized (n = 6), metastatic (n = 7), KIT-mutant (n = 10), and PDGFRA-mutant (n = 3). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (compared with non-GIST TFs; *P < 0.001). (E) Sensitivity score comparing GIST-associated TFs (n = 21) with non-GIST TFs (n = 794) present in Project DRIVE data for GIST-T1 (Welch’s t test; *P < 0.005). (F) Scatterplot of average GIST tumor FPKM (n = 13) and sensitivity score from all TFs in Project DRIVE. Data points are colored according to grouping in GIST-associated TFs (red), TFs with unique SEs in the GIST-T1 cell line used in Project DRIVE compared with all GIST tumors (yellow), or non-GIST TFs (gray). (G and H) Plot of sensitivity score and cell line rank (n = 387) for the GIST-associated TFs FOXF1 (G) and HIC1 (H). (I and J) Plot of sensitivity score and cell line rank for non-GIST TFs YBX1 (I) and ZNF207 (J); the values for the GIST-T1 cell line are indicated in blue.

To assess for preferential expression of these GIST-associated TFs, we transcriptionally profiled GIST tumor subtypes by RNA-seq. Compared with other TFs, the GIST-associated TFs are more highly expressed in GIST tumors and tumor subtypes (Fig. 2D). To confirm their functional role in GIST biology, we applied dependency screening (21) in the GIST cell line GIST-T1, which shows greater reliance upon the expression of GIST-associated TFs in vitro compared with other TFs (Fig. 2E). A scatterplot of tumor TF expression and sensitivity score reveals several TFs that are both highly expressed in tumors and functionally required in vitro for cellular viability (Fig. 2F). Several of these GIST-associated TFs were uniquely required for GIST-T1 cell growth among a panel of 387 cell lines, including FOXF1 and HIC1 (Fig. 2 G and H). In contrast, other TFs outside the GIST regulatory circuit that were expressed in tumors and required for GIST-T1 cell growth were not unique to GIST (Fig. 2 I and J), suggesting their more general, non–GIST-centric cellular function. Taken together, we have identified a subset of TFs important for GIST biology through epigenetic, transcriptional, and functional dependency methods. These results define the transcriptional circuitry underlying the GIST neoplastic program, advance our understanding of GIST biology, and identify candidate biomarkers for diagnosing and treating this disease.

Identification of HAND1 as a Unique Dependency in Metastatic GIST.

Augmentation of a cellular transcriptional network with the emergence or loss of accessory TFs can give rise to a neoplastic program (9, 10). Hypothesizing that this process may underlie metastatic behavior in GIST, we analyzed the differences in enhancer peaks between localized and metastatic GIST tumors and KIT-dependent cell lines (Fig. 3A), focusing on TFs and transcriptional coactivators. This analysis identified HAND1 as a TF with uniquely engaged enhancers in metastatic GIST tumors and six KIT-dependent cell lines derived from metastatic disease (Fig. 3B).

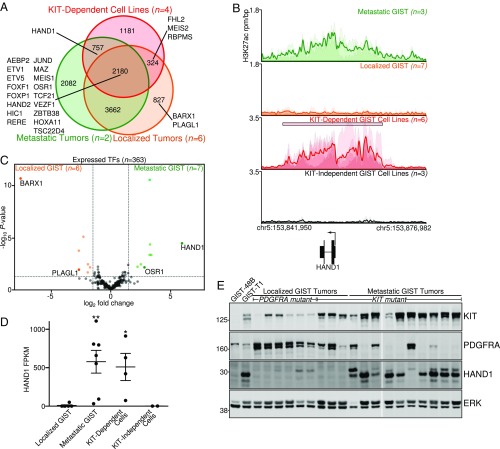

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of TFs enriched in metastatic GIST identifies HAND1. (A) Venn diagram of enhancer peaks comparing metastatic (n = 2) and localized GIST (n = 6) tumors and parental KIT-dependent GIST cell lines (n = 4). Transcriptional regulatory genes are listed, with HAND1 being unique to the metastatic tumors and BARX1 to localized tumors. (B) Meta tracks of GIST tumors and cell lines at the HAND1 locus. y-axis heights are variable to emphasize peak morphology. The SE region is indicated with a rectangle. (C) Volcano plot of RNA-seq data in all expressed TFs comparing localized and metastatic GIST tumors. Differentially and highly expressed TFs are labeled. (D) FPKM of HAND1 in tumor and cell line subtypes. RNA-seq samples include localized tumors with either KIT (n = 3) or PDGFRA (n = 3) mutations, KIT-mutant metastatic tumors (n = 7), KIT-dependent cell lines (n = 4), and KIT-independent cell lines (n = 2). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (compared with localized GIST tumors; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (E) Western blot of localized and metastatic GIST tumors probing for KIT, PDGFRA, HAND1, or ERK as a loading control. The tumor’s activating mutation (KIT or PDGFRA) is indicated above the lane.

To corroborate these findings, we further scrutinized gene expression profiling in different clinical subtypes of GIST. Globally, localized and metastatic GIST tumors cluster separately, with enrichment of different cellular pathways between these disease states (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). However, less than 5% of expressed genes were differentially expressed between localized and metastatic disease (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C), consistent with continual dependence upon a preserved RTK-driven program throughout all stages of disease (22), and there remained preferential expression of the same SE-associated genes across all disease subtypes (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D).

By RNA-seq, HAND1 was the most significantly up-regulated transcription factor expressed in metastatic tumors (Fig. 3 C and D). By contrast, ETV1 enhancers and expression were preserved between localized and metastatic GIST (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). HAND1 is a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) TF that can homo- or heterodimerize with other bHLH factors, including HAND2, and has been described in the orchestration of cardiac morphogenesis and disease (23). HAND1 has further been found to antagonistically associate with FHL2 (24), and FHL2 enhancer and gene expression are notably diminished in metastatic GIST tumors (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D). HAND2 expression is also reduced in metastatic tumors (SI Appendix, Fig. S5E), suggesting increased homodimerization of HAND1 or alternate binding partners in metastatic GIST. HAND1 protein was only present in metastatic GIST tumors and KIT-dependent cell lines by Western blot (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). Of note, KIT and PDGFRA expression positively correlate with the primary RTK mutation (Fig. 3E, Top two panels and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 F and G).

Of parallel significance, several transcription factors are lost in metastatic disease. The most profoundly suppressed is BARX1 (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 H and I), a member of the Bar homeobox gene family characterized in development and as a putative tumor suppressor (25). PLAGL1, a putative tumor suppressor (26), is also significantly reduced in metastatic GIST (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5J).

To determine where in the genome HAND1 binds and whether these regions may portend disease relevance, we performed ChIP-seq for HAND1. As a comparator, we also performed ChIP-seq for ETV1, whose enhancer is preserved across tumor samples and contribution to GIST biology has been previously explored (13). Both HAND1 and ETV1 bind to many of the H3K27ac-defined TEs and SEs shared among GIST tumors and KIT-dependent cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–E). ChIP-seq disclosed greater HAND1 enrichment at the KIT enhancer domain compared with ETV1 (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S6C), which prompted further functional evaluation of these TFs in KIT expression and cellular viability.

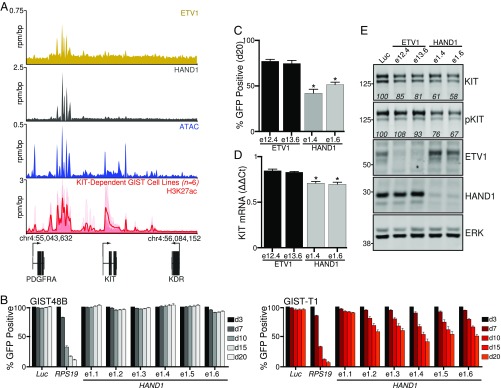

Fig. 4.

HAND1 is required for GIST cellular proliferation and KIT expression. (A) ChIP-seq of ETV1 and HAND1, ATAC-seq, and H3K27ac ChIP-seq meta tracks at the KIT locus. (B) CRISPR/Cas9 GFP-competition assay over time with sgRNAs targeting HAND1 in the KIT-independent GIST48B cell line (grayscale) and KIT-dependent cell line GIST-T1 (red). sgRNAs against luciferase (Luc) and RPS19 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Gene-specific sgRNAs are named after the targeted exon. Mean ± SEM; n = 4. (C) Comparison of percent GFP-positive cell depletion at day 20 arising from ETV1 and HAND1 sgRNAs in GIST-T1. Mean ± SEM; n = 4. (D and E) Relative KIT mRNA levels by RT-PCR normalized to Luc sgRNA control and Western blot for the indicated proteins following 10 d of treatment with the indicated control or ETV1 or HAND1 sgRNAs in GIST-T1. Mean ± SEM; n = 3. Values within the Western blots represent average band signal intensity across three independent experiments with experimental samples processed in parallel and normalized to Luc sgRNA control. Data in C and D were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (compared with Luc sgRNA control; *P < 0.05).

To compare the relative contribution of ETV1 and HAND1 to GIST biology, we utilized a single-guide RNA (sgRNA)–GFP competition assay in which sgRNAs against ETV1 or HAND1 were introduced together with GFP, and effects on cellular fitness were determined by quantitative changes in GFP-positive cell abundance over time (27). Compared with the KIT-independent cell line GIST48B, which expresses neither ETV1 nor HAND1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), the KIT-dependent GIST-T1 cells subjected to Cas9 cleavage at either gene showed decreased fitness over time (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6F). sgRNAs against RPS19 and luciferase were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The most active sgRNAs in the assay correlated with the greatest depletion of protein expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S6G). Similar results were seen in the slower-growing KIT-dependent cell line GIST430 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 H and I). The decrease in cellular fitness arising from HAND1 loss was significantly greater than that from ETV1 in GIST-T1 (Fig. 4C). Hypothesizing that HAND1 contributed to the expression of the principal GIST oncogene, KIT, we evaluated KIT levels by RT-PCR and Western blot 10 d after introduction of the most active ETV1 or HAND1 sgRNAs in GIST-T1. Consistent with this hypothesis, HAND1 loss led to a decrease in KIT mRNA levels (Fig. 4D) and a decrease in both KIT and phospho-KIT protein levels (Fig. 4E), compared with ETV1 sgRNAs or control conditions. These results implicate HAND1 in the regulation of KIT gene expression and suggest its essential role, together with BARX1 loss, in the development of metastatic disease.

Expression of BARX1 and HAND1 Predicts Clinical Outcome.

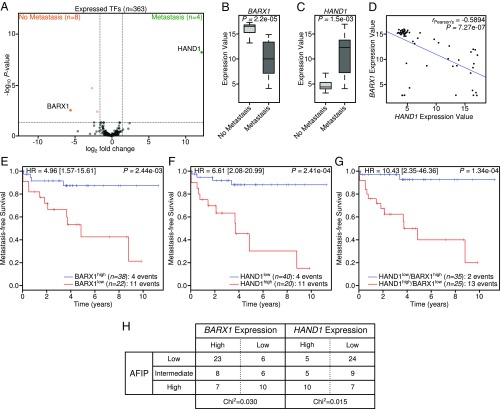

To test the hypothesis that BARX1 and HAND1 expression can predict metastatic potential, we evaluated independent expression datasets of localized and resected primary GIST tumors from patients with longitudinal clinical follow-up (28). By RNA-seq, HAND1 was the only TF up-regulated in localized disease that would later develop metastasis, while BARX1 was the TF most enriched in localized GIST without future metastasis (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

HAND1 and BARX1 expression predicts subsequent metastasis in primary GIST. (A) Volcano plot of RNA-seq data of TFs from untreated, localized primary GIST comparing tumors with and without subsequent metastasis. (B and C) Boxplots showing array expression values of BARX1 (B) and HAND1 (C) and in cases of untreated, localized primary GIST tumors that did (n = 15) or did not (n = 45) subsequently develop metastatic disease; Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (D) Scatterplot showing negative correlation between HAND1 and BARX1 expression (n = 60). (E–G) Kaplan–Meier analysis of metastasis-free survival in 60 primary GIST tumors stratified by BARX1 expression, HAND1 expression, or combined HAND1/BARX1 expression. HR, hazard ratio. (H) Table of BARX1 and HAND1 expression values in primary GIST tumors separated by AFIP risk category. The χ2 test P value evaluating association of AFIP stratification versus BARX1 or HAND1 expression is indicated.

Next, we analyzed a larger, clinically annotated dataset with gene expression from localized, untreated tumors quantified by microarray (29). In this dataset, BARX1 expression was again correlated with no future disease recurrence (Fig. 5B), while HAND1 was expressed in localized tumors that subsequently developed metastasis following primary resection (Fig. 5C). There was a significant anticorrelation between BARX1 and HAND1 expression in these primary tumors (Fig. 5D). Based solely upon expression of BARX1 or HAND1, or combined BARX1/HAND1 expression values, metastasis-free survival from the date of initial diagnosis disclosed a significantly higher risk of metastasis with low BARX1 expression (Fig. 5E), high HAND1 expression (Fig. 5F), or combined low BARX1 and high HAND1 expression (Fig. 5G). The combination of low BARX1 and high HAND1 had the greatest predictive value for the development of metastatic disease, with a hazard ratio of 10.43 (range 2.35 to 46.36). Both BARX1 and HAND1 expression values independently associate with tumor risk stratification by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) criteria for GIST (Fig. 5H). In summary, these data describe a network of TFs responsible for the core GIST transcriptional program and identify accessory TFs that augment this program to inculcate metastatic behavior.

Discussion

In the present study, we describe the enhancer landscape of GIST, analyzing cell lines and fresh-frozen tumor specimens derived from localized or metastatic disease. A common set of characteristic enhancers were found to regulate GIST in vivo and in vitro, many of which were dependent upon trophic kinase signaling. The enhancer pattern in KIT- and PDGFRA-mutant tumors was largely homogeneous, reflecting these neoplasms’ cellular origin from the interstitial cell of Cajal or related precursor cells (30, 31) and use of a conserved repertoire of TFs. Further, SDH-deficient GIST tumors showed an enhancer pattern similar to that of kinase-mutant GIST, suggesting an identical cellular origin.

In addition to the redemonstration of established tumor markers and GIST-related genes (e.g., ANO1, CD34, PRKCQ, SPRY4, ETV1), this analysis identified many unique GIST-associated genes that may be useful in the diagnosis, prognosis, or targeted treatment of this disease. Importantly, by incorporating patient-derived tumor samples into our study of GIST, we were able to focus our in vitro studies on genes relevant to the human disease rather than genes and processes arising from in vitro selection. As an example, HAND1 was found to be unique to metastatic GIST tumors, and GIST cells derived from metastatic tumors required this TF for normal KIT gene expression and cellular proliferation. The role of HAND1 in metastatic GIST, binding to many of the established enhancers characteristic of GIST tumors, is reminiscent of the elaboration of Myc and its associated transcriptional changes in many other tumor types (32). HAND1 may function as a transcriptional amplifier of the oncogenic GIST program as opposed to turning on or off other genes, which in concert with the loss of accessory TFs highly expressed in localized tumors (e.g., FHL2, BARX1, PLAGL1) may lead to metastatic behavior.

A challenge in the clinical management of GIST is accurate prognostication of disease recurrence or progression to guide the use of adjuvant therapy. Currently, only patients with GIST at high risk of recurrence based on tumor mitotic rate, size, and location are treated with adjuvant imatinib (3). However, lacking more molecularly defined risk factors, this leaves a large number of patients untreated who will subsequently develop disease recurrence, and may be overtreating a subset of high-risk patients. By taking a rational approach to understanding the transcription factor circuitry driving GIST biology, we describe a network of core TFs expressed in all disease states that are predicted to function cooperatively and are important for GIST cell viability in vitro. We further define two accessory TFs, BARX1 and HAND1, which augment this network, and their antagonistic expression is closely linked to the development of metastatic disease. Additional studies are warranted to further test these unique prognostic markers of GIST clinical outcome. This type of experimental approach generates a rich dataset urgently needed to improve the understanding of GIST, and is feasible to translate into other sarcomas that commonly lack biological understanding, diagnostic markers, prognostic indicators, or targeted therapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Virus Production.

All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma infection and are not listed in the International Cell Line Authentication Committee database. Human embryonic kidney 293FT (R70007; Invitrogen), the GIST cell lines GIST-T1, GIST-T1/816, GIST430, GIST430/654, GIST430B, GIST882, GIST48, GIST48B, and GIST226 (33), MaMel (34), and EWS502 (35) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 mg/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin, except GIST882, which was grown in RPMI with identical supplementation. See SI Appendix, Table S1 for descriptions of each cell line’s KIT mutation. hMSCs (SCRC-4000; ATCC) were grown according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. To ensure cell line identity, KIT exons were sequenced to confirm the expected coding mutations (primers used for sequencing are listed in Dataset S3). Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Lentiviral production and stable cell line generation were performed as previously described (36). Briefly, 293FT cells were cotransfected with pMD2.G (12259; Addgene), psPAX2 (12260; Addgene), and the lentiviral expression plasmid of interest. Viral supernatant was collected at ∼72 h, and debris was removed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min. Cells were transduced with viral supernatant and polybrene at 8 μg/mL by spinoculation at 680 × g for 60 min.

ChIP-Seq and ATAC-Seq.

Tumor samples.

Fresh-frozen tumor samples were obtained from patients consenting to a Dana-Farber Cancer Institute IRB-approved research protocol and undergoing surgery at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Localized tumors were defined as those completely resected from their primary site without neoadjuvant therapy. Metastatic tumors were defined as cases where cytoreductive surgery was performed for disease progression or complication while concurrently on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, when macroscopically complete (R0/R1) resection could not otherwise be performed. We attempted ChIP-seq in a total of 26 GIST tumors, with failure rates highest in samples derived from metastatic tumors owing to sample quality influenced in part by prolonged surgery and treatment effect.

ChIP-seq.

Approximately 75 mg of minced tumor tissue or 2 to 10 × 107 cells were incubated in 1% formaldehyde for 15 or 10 min, respectively. Following incubation, excess formaldehyde was quenched with glycine at 0.125 M. Tumors were then homogenized with a Tissue-Tearor Homogenizer (BioSpec). Samples were washed with PBS, and intact nuclei were extracted by serial incubations in lysis buffers for 10 min at 4 °C: lysis buffer 1 [50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1× Halt protease inhibitor mixture (Thermo Scientific)]; and lysis buffer 2 (10 mM Tris, pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1× Halt protease inhibitor mixture). Nuclei were spun at 1,350 × g for 5 min between lysis steps and then resuspended in sonication buffer with SDS (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.5% SDS, 1× Halt protease inhibitor) before Bioruptor sonication (high-output sonication in 30-s intervals; Diagenode) for 20 to 25 min in 15-mL TPX tubes. Sonicated samples were spun at 20,000 × g for clarification, and supernatant was diluted 1:5 in sonication buffer before overnight incubation with Dynabeads (Life Technologies) prebound with antibody (H3K27ac, ab4729, Abcam; ETV1, ab81086, Abcam; HAND1, OTI1G10, OriGene) per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sonicated chromatin (50 μL) was saved as input control. Following overnight immunoprecipitation, samples were washed serially with sonication buffer, sonication buffer with 500 mM NaCl, LiCl buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM LiCl, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate), and TE-NaCl buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl). Samples were eluted by heating at 65 °C for 15 min in elution buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS), and cross-links were reversed by incubation at 65 °C for 16 h. DNA was purified by serial incubation with 0.2 mg/mL RNaseA (Thermo Scientific) and then proteinase K (Ambion), followed by extraction with phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitation. Libraries for single-end 75-bp sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq 500 were prepared with a ThruPLEX DNA-Seq Kit (Rubicon Genomics), with sample analysis and quantitation using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies) and 2200 TapeStation (Agilent). ETV1 and HAND1 ChIP-seq were performed in the GIST-T1 cell line.

ATAC-seq.

Approximately 50,000 cells were incubated in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630) for nuclear isolation. Washed nuclei were incubated with Nextera transposase (Illumina) and DNA was prepared per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Libraries for sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq 500 were prepared using the Nextera DNA Preparation Kit (Illumina).

RNA-Seq.

Fresh-frozen GIST tumors were obtained and cell lines were grown as described. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Plus Kit (Qiagen). RNA concentration was measured by NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific) and quality was determined by Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Libraries for Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencing were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina), and equimolar multiplexed libraries were sequenced with single-end 75-bp reads.

Sequencing Data Analysis.

Computational methods used for data analysis have been described previously (15), and are available from the J.E.B. laboratory github page (https://github.com/BradnerLab/pipeline).

Sequencing read alignment and annotation.

All ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq data were aligned to the human reference genome assembly hg19, GRCh37 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001405.13/), using Bowtie2 (37) (version 2.2.1), and gene annotations by Gencode annotation release 19 (https://www.gencodegenes.org/releases/19.html). Normalized read density was calculated using the bamliquidator (version 1.0) read density calculator. Aligned reads were extended by 200 bp, and the density of reads per base pair was calculated. In each region, the density of reads was normalized to the total number of million mapped reads, generating read density in units of reads per million mapped reads per base pair (rpm/bp).

Peak finding, enhancer classification, and clustering.

Peak finding was performed using Model-based Analysis for ChIP-Seq [MACS (38), version 1.4.2]. As control, matched input chromatin was used to generate background signal for peak determination. Calling of typical enhancers and superenhancers was performed using the ROSE2 (12) software package. For SE determination, an optimized stitching region was used to cluster H3K27ac peaks into contiguous enhancers at each enhancer region. SEs from each sample were hierarchically clustered on pattern similarity of median normalized H3K27ac enhancer signal as determined using pairwise Pearson correlations.

ChIP-seq data representations.

Ranked enhancer plots were generated by merging H3K27ac signal across subgroup samples and ranking by H3K27ac signal. Venn diagrams of enhancer peaks required that an enhancer peak be conserved among all samples to be considered present in the subgroup. Meta tracks of H3K27ac ChIP-seq signal were generated, with each individual sample displayed as a transparent track in rpm/bp and the opaque line representing the average signal across all samples. Waterfall plots showing log2 fold change in SE regions between groups were generated by comparing compiled H3K27ac signal at SEs present in at least one sample per group. Heatmap visualizations of ChIP-seq data were generated using ChAsE software (39). For inclusion of ChIP-seq tumor samples in genome-wide enhancer comparisons, samples were required to have at least 185 SEs defined by ROSE2 with SE H3K27ac signal over 1,000 rpm.

TF enrichment and regulatory circuitry.

GIST-associated TFs were determined by compiling a list of all TFs with an associated SE shared between the highest-quality tumor ChIP-seq datasets (n = 8). Candidate TFs were required to be expressed in GIST tumors [n = 13, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) > 12] and cell lines (n = 4, FPKM > 12). The GIST transcriptional core regulatory circuitry was determined by identifying SE-associated TFs predicted to bind cooperatively to SEs in an autoregulatory loop, as previously described (19). TF motif analysis in ATAC peaks within each SE was performed using Find Individual Motif Occurrences (FIMO) (40), where motifs were known. Extended regulatory circuitry was defined as GIST-associated TFs that are outside of, but connected to, the core regulatory circuitry. With each TF displayed as a node, edges were drawn between predicted binding partners to indicate core and extended regulatory circuitry relationships. Dataset S2 indicates whether the GIST-associated TFs have an SE, TE, or absent enhancer in different ChIP-seq samples. TF dependency and sensitivity scores were derived from Project DRIVE (21) shRNA screening performed in GIST-T1 cells; not all GIST-associated TFs were included in the screen.

RNA-seq alignment and analysis.

RNA-seq data, cell count-normalized where appropriate, were aligned using STAR (41), with expression quantification using Cufflinks (42) to generate gene expression values in FPKM units. Hierarchical clustering of RNA-seq data was performed using Cluster 3.0 (43) and visualized with Java Treeview (44). Gene set enrichment analysis (45) was performed using CP:REACTOME in the Molecular Signatures Database (software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/). Differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data was performed using edgeR (46), with statistical analyses reporting corrected P values. For TF differential expression, candidate TFs were required to have >10 rpm averaged across tumors and detectable levels of expression (>1 rpm) in the lower-expressing group. Array gene expression analysis was performed on 60 untreated, localized primary GIST tumors as previously described (29) using Whole Human 44K Genome Oligo Arrays (Agilent Technologies). The mean expression level was used as the cutoff to define high and low expression values.

Immunoblotting.

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min to remove genomic DNA and debris. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid-based assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Protein samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE and Western blotting with the following antibodies: KIT (D13A2, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-KIT (D12E12, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), ERK (3A7, 1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-ERK (4370, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), HAND1 (OTI1G10, 1:500; OriGene), ETV1 (ab81086, 1:500; Abcam), AEBP2 (ab107892, 1:1,000; Abcam), MEIS1 (ab124686, 1:1,000; Abcam), PDGFRA (D1E1E, 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), and GAPDH (sc-365062, 1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). ERK and GAPDH were used as loading controls. Western blots were probed with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies and detected using the Odyssey CLx Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Quantification of band intensity was performed using Image Studio (LI-COR Biosciences). Immunoblots shown are representative of at least three independent in vitro experiments.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Tumors were homogenized or cells were trypsinized and washed in PBS for RNA extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Libraries of cDNA were made using the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Select Master Mix (Life Technologies) on a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). Relative mRNA levels were calculated by the ΔΔCt method using GAPDH expression as reference, and normalized to expression in the GIST-T1 cell line where indicated. All RT-PCR amplicons were verified by gel electrophoresis and DNA sequencing. Primers used for RT-PCR are detailed in Dataset S3.

Cloning and CRISPR Assays.

Cell lines stably expressing a human codon-optimized Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (73310; Addgene) were generated by viral transduction. CRISPR guide RNAs were cloned into Lenti-sgRNA-EFS-GFP (65656; Addgene) (27). All sgRNAs were designed using the CRISPR Design Tool (crispr.mit.edu/) and detailed in Dataset S3. Selected sgRNAs were designed to target the upstream coding region or DNA-binding domain of TFs, and named according to the targeted exon. For sgRNA–GFP competition assays, flow cytometry to quantify GFP-expressing cells was performed in 96-well plates using a Guava easyCyte Flow Cytometer.

Statistical Analysis.

Center values, error bars, P-value cutoffs, number of replicates, and statistical tests are identified in the corresponding figure legends. Replicates represent separate tumors or unique cell lines where indicated, or in experiments using the same cell line the replicates represent separate treatments of cultures from the original stock unless otherwise specified. Error bars are shown for all data points, with replicates as a measure of variation within each group. Samples sizes were not predetermined, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiment or outcome assessment. Kaplan–Meier analysis of metastasis-free survival was calculated from the date of initial diagnosis to the date of first metastasis, relapse, last follow-up, or death. Hazard ratios and P values were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard model.

Data and Materials Availability.

Novel ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, and RNA-seq data presented in this publication are available online through Gene Expression Omnibus accession no. GSE95864. RNA-seq data of primary GIST tumors (Fig. 5A) are available through the Sequence Read Archive under accession no. SRP057793. Microarray data are available under ArrayExpress accession no. E-MTAB-373.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nacef Bahri for assistance with cell lines, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Molecular Biology Core Facilities, and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital tissue bank. Rick Kaitz, Charles Lin, Andrew J. Wagner, Suzanne George, Jennifer Perry, Leonora Linden, Richard Wale, Nancy Louise, and Al Lou contributed essential discussion. We thank J.E.B. and S.A.A. laboratory members and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Hematology/Oncology Fellowship Program for support. We are indebted to the patients and families who donated clinical samples that enabled this research. Support for this work was provided by the following sources: Erica’s Entourage Sarcoma Epigenome Project Fund (J.E.B. and G.D.D.), the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Mittelman Fellowship (to M.L.H.), the American Society of Clinical Oncology Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (to M.L.H.), and the Spivak Faculty Advancement Fund (M.L.H.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: R.Z. is currently an employee at C4 Therapeutics. S.A.A. is a consultant for Epizyme Inc., Vitae Inc., and Imago Biosciences. G.D.D. reports financial relationships with Ariad, Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Kolltan Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. J.E.B. is an employee, shareholder, and executive of Novartis Pharmaceuticals. J.E.B. is a scientific founder of Syros Pharmaceuticals, SHAPE Pharmaceuticals, Acetylon Pharmaceuticals, Tensha Therapeutics (now Roche), and C4 Therapeutics, and is the inventor on intellectual property licensed to these entities. None of these relationships constitute a conflict of interest for the present work. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE95864).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1802079115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Burningham Z, Hashibe M, Spector L, Schiffman JD. The epidemiology of sarcoma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2:14. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demetri GD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Mehren M. Management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:1059–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whyte WA, et al. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hnisz D, et al. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell. 2013;155:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang J, et al. Dynamic control of enhancer repertoires drives lineage and stage-specific transcription during hematopoiesis. Dev Cell. 2016;36:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hnisz D, et al. Convergence of developmental and oncogenic signaling pathways at transcriptional super-enhancers. Mol Cell. 2015;58:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, et al. Identification of focally amplified lineage-specific super-enhancers in human epithelial cancers. Nat Genet. 2016;48:176–182. doi: 10.1038/ng.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansour MR, et al. An oncogenic super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding intergenic element. Science. 2014;346:1373–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1259037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Northcott PA, et al. Enhancer hijacking activates GFI1 family oncogenes in medulloblastoma. Nature. 2014;511:428–434. doi: 10.1038/nature13379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapuy B, et al. Discovery and characterization of super-enhancer-associated dependencies in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:777–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovén J, et al. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell. 2013;153:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi P, et al. ETV1 is a lineage survival factor that cooperates with KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Nature. 2010;467:849–853. doi: 10.1038/nature09409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ran L, et al. Combined inhibition of MAP kinase and KIT signaling synergistically destabilizes ETV1 and suppresses GIST tumor growth. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:304–315. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin CY, et al. Active medulloblastoma enhancers reveal subgroup-specific cellular origins. Nature. 2016;530:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature16546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sur I, Taipale J. The role of enhancers in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:483–493. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang HJ, et al. Correlation of KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α mutations with gene activation and expression profiles in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncogene. 2005;24:1066–1074. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian S, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) with KIT and PDGFRA mutations have distinct gene expression profiles. Oncogene. 2004;23:7780–7790. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saint-André V, et al. Models of human core transcriptional regulatory circuitries. Genome Res. 2016;26:385–396. doi: 10.1101/gr.197590.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald ER, III, et al. Project DRIVE: A compendium of cancer dependencies and synthetic lethal relationships uncovered by large-scale, deep RNAi screening. Cell. 2017;170:577–592.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George S, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib in patients with metastatic and/or unresectable GI stromal tumor after failure of imatinib and sunitinib: A multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2401–2407. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bär H, Kreuzer J, Cojoc A, Jahn L. Upregulation of embryonic transcription factors in right ventricular hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2003;98:285–294. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill AA, Riley PR. Differential regulation of Hand1 homodimer and Hand1-E12 heterodimer activity by the cofactor FHL2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9835–9847. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9835-9847.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang G, et al. Loss of Barx1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through up-regulating MGAT5 and MMP9 expression and indicates poor prognosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:71867–71880. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdollahi A, et al. LOT1 (PLAGL1/ZAC1), the candidate tumor suppressor gene at chromosome 6q24-25, is epigenetically regulated in cancer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6041–6049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi J, et al. Discovery of cancer drug targets by CRISPR-Cas9 screening of protein domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:661–667. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lesluyes T, et al. RNA sequencing validation of the Complexity INdex in SARComas prognostic signature. Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lagarde P, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:826–838. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin BP, Heinrich MC, Corless CL. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2007;369:1731–1741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu JJ, Rothman TP, Gershon MD. Development of the interstitial cell of Cajal: Origin, Kit dependence and neuronal and nonneuronal sources of Kit ligand. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:384–401. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000201)59:3<384::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin CY, et al. Transcriptional amplification in tumor cells with elevated c-Myc. Cell. 2012;151:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garner AP, et al. Ponatinib inhibits polyclonal drug-resistant KIT oncoproteins and shows therapeutic potential in heavily pretreated gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5745–5755. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang R, Wallace AR, Schadendorf D, Rubin BP. The phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase pathway is central to the pathogenesis of Kit-activated melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:714–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer S, Yu LK, Demetri GD, Fletcher JA. Heat shock protein 90 inhibition in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9153–9161. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hemming ML, Elias JE, Gygi SP, Selkoe DJ. Proteomic profiling of gamma-secretase substrates and mapping of substrate requirements. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng J, Liu T, Qin B, Zhang Y, Liu XS. Identifying ChIP-seq enrichment using MACS. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1728–1740. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Younesy H, et al. ChAsE: Chromatin analysis and exploration tool. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3324–3326. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant CE, Bailey TL, Noble WS. FIMO: Scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1017–1018. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobin A, et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Hoon MJL, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview—Extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3246–3248. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.