Abstract

Background

Most infants with congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection are born to seropositive women as a result of maternal CMV non-primary infection (reinfection or reactivation). Although infected children are known to transmit CMV to their seronegative mothers, the frequency and magnitude of non-primary maternal CMV infection after exposure to viral shedding by children in their household has not been characterized.

Methods

A cohort of Ugandan newborns and their mothers were tested weekly for CMV by quantitative PCR of oral swabs. Infant primary infection and maternal non-primary infection were defined by the onset of persistent high-level oral CMV shedding. Strain-specific antibody testing was used to assess maternal reinfection. Cox regression models with time-dependent covariates were used to evaluate risk factors for non-primary maternal infection.

Results

Non-primary CMV infection occurred in 15 of 30 mothers, all following primary infection of their infants by a median of 6 weeks (range 1 to 10) in contrast to none of the mothers of uninfected infants. The median duration of maternal oral shedding lasted 18 weeks (range: 4 – 42) reaching a median maximum viral load of 4.69 log copies/ml (range 3.22 – 5.64). Previous-week infant CMV oral quantities strongly predicted maternal non-primary infection (hazard ratio 2.32 per log10 DNA copies/swab increase; 95% CI 1.63, 3.31). Maternal non-primary infections were not associated with changes in strain-specific antibody responses.

Conclusions

Non-primary CMV infection was common in mothers following primary infection in their infants, consistent with infant-to-mother transmission. Since infants frequently acquire CMV from their mothers, e.g. through breast milk, this suggests the possibility of “ping-pong” infections. Additional research is needed to characterize the antigenic and genotypic strains transmitted among children and their mothers.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, reinfection, primary infection, shedding

INTRODUCTION

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common congenital infection and an important cause of sensorineural hearing loss and intellectual disability in children worldwide (1, 2). Maternal CMV infection acquired prior to conception offers incomplete protection against transmission to the fetus, and most cases of congenital CMV infection are associated with non-primary maternal CMV infection during pregnancy (3, 4). Non-primary CMV infection has been defined by detection of active CMV infection in a previously infected individual after a period of at least four weeks without detectable virus during active surveillance (5), and results from either reactivation of endogenous (latent) virus or reinfection by exogenous virus (6–8). Reinfection is defined as detection of a CMV strain that is distinct from the strain that was the cause of the patient’s original infection; reactivation is assumed if the two strains are the same (5).

Postnatal CMV primary infection in infants often occurs through breastfeeding (9–11), but horizontal transmission through shedding in saliva and urine of other children is also common. Following primary CMV infection, young children shed virus at high levels for prolonged periods in saliva and urine (12, 13). Exposure to young children is therefore a risk factor for primary CMV infection in women of childbearing age (14–16). In adults with chronic infection, transient viral shedding in saliva or urine has been described (17–20). CMV shedding in breast milk occurs in 40–99% of lactating seropositive women and leads to postnatal transmission (21–25).

This study presents the analysis of oral CMV shedding patterns in a well-characterized prospective cohort of households of mothers and children in Uganda, and describes the novel observation that non-primary CMV infection in women commonly occurs shortly after postnatal primary infection of their infants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study cohort and data collection

A birth cohort of 32 mother-infant pairs was established in Uganda, as previously described (11). Briefly, pregnant women attending prenatal care in Kampala were recruited between 2008 and 2010. Eligibility required having documented HIV-1 status, at least one other pre-school aged (“secondary”) child living in the home, and stable residence in the Kampala area. After delivery, oral swab samples were collected from the women, the newborns and their household contacts weekly. A standardized questionnaire was administered at each study visit, which included information about breastfeeding and other maternal behaviors that might expose principal children to saliva (pre-mastication of food, sharing drinking cups or eating utensils, rubbing saliva into a bite or wound, or kissing on the mouth) during the previous week. Blood samples were collected from the newborn at 6 weeks of age, and every four months thereafter. Blood samples were collected from the mother at delivery and 1 year later. School-aged children and fathers were rarely at home when study visits took place, and therefore were not included. The study was approved by the relevant ethics review boards in Uganda, the U.S. and Canada.

Sample processing and viral testing

Oral swabs and plasma samples were tested for CMV using real-time quantitative (q)PCR as described (11). The limit of detection was 150 copies/mL for swabs and 50 copies/mL for plasma.

Definitions of infant primary infection

Detection of viral DNA in the plasma or ≥2 consecutive oral swabs of sufficient quantity (≥3.5 log10 copies/mL) defined primary infection (11). This threshold allows for the exclusion of transient episodes of oral shedding that are not consistent with primary infection in infants (26). The onset of primary infection was defined as the date of the earliest positive PCR test within a window period ≤28 days prior to the samples used to meet the definition of primary infection. Newborns who met the definition of primary infection at the time of their first PCR sample (obtained at ≤2 weeks of life) were considered to have been infected in utero and excluded.

Definitions of maternal non-primary infection

We defined maternal non-primary infection by detection of ≥3 log10 copies/mL of CMV DNA in ≥2 consecutive weekly oral swabs. This lower viral threshold than the one used for primary infection in infants was chosen to allow for reduced viral loads in non-primary compared to primary infection and in adults compared to infants (27). The start of an episode was defined as the time of the first positive swab in this series that followed 2 consecutive negative swabs. The end of the recurrence was defined by the first 2 consecutive negative swabs.

CMV serology

Diagnostic serology for CMV infection was performed using ELISA kits (Wampole (Alere), Boucherville, Quebec). CMV strain–specific antibody responses were determined using polymorphisms in antibody binding sites within envelope glycoproteins gH and gB, between the 2 prototypical laboratory strains of CMV, AD169 and Towne. The detection of new antibody specificities to either epitope (AD169 or Towne) on gH or gB when comparing delivery to year one follow-up serum samples was considered evidence of acquisition of a new viral strain (reinfection) (6, 7).

Statistical analyses

We assessed the following risk factors for maternal non-primary infection: primary infant CMV infection, maternal HIV status, and whether there was an oral contact between mother and infant. We defined oral contact using questionnaire data regarding whether a mother reported sharing saliva or food in the previous week (11). We also analyzed household exposure by including the CMV shedding from the infants and the secondary children in the household. For households with multiple secondary children, we used the maximum value recorded in a given week as the shedding value. All variables were assessed between infant birth until either maternal non-primary infection or the end of follow-up, whichever came first.

We analyzed the variables simultaneously using a Cox proportional hazard models with time-dependent covariates to account for the time to event data and censoring in the cohort (28, 29). Maternal HIV was included as a time-independent variable while oral contacts, infant oral viral load, and secondary child oral viral load from the previous week were included as time-dependent covariates. Infant infection status was defined in this cohort previously using their viral shedding data (11) and is correlated with persistent shedding (30), so infant viral load was considered a continuous proxy for infant infection status. To handle missing data, we used the last observation carried forward. A sensitivity analysis using complete case analysis is presented in Supplemental Digital Content 1 (Table).

Model selection was performed as follows: we started with the full model, then selected variables statistically significant at the 0.1 level. Statistical programming was done using the R language (CRAN). The Cox survival model with time-dependent covariates was estimated using the survival package.

RESULTS

Study Cohort

After exclusion of 2 cases of congenital CMV infection, women from 30 households were followed for a median of 51 weeks (range 3–52). All women had established CMV infection at delivery based on detection of CMV-specific IgG in serum. Fifteen women were HIV-infected, with a median CD4 at delivery of 441 cells/mm3 (range 385 to 885). There were 21 households with only one secondary child, 5 households with 2, and 4 households with 3. Of the 30 infants, 17 acquired CMV while the mothers were being followed. None of the infants were infected with HIV at birth or during follow-up.

Frequency and Timing of Maternal Non-Primary CMV Infection

Non-primary CMV infection occurred in 15 mothers, all of whom had infants with primary CMV infection (Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2 [figure]). Non-primary infections occurred at a median of 15 weeks (range 6 to 43) after delivery and 6 weeks (range 1 to 10) after primary infection of the infant (see figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2). The median duration of the recurrence episode was 18 weeks (range 4 to 42). Among women who experienced a non-primary infection, maximum oral viral load ranged from 3.22 to 5.64 log10 copies/swab. Maternal non-primary infection was not associated with positive qPCR in blood at one year.

Table 1.

Summary of exposures by maternal CMV non-primary infection statusa

| N | Maternal non- primary infection N=15 |

No maternal non-primary infection N=15 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Follow-up weeks, median (range) | 30 | 51 (15, 52) | 51 (3, 52) |

|

|

|||

| CMV Primary infection in infants, N (%) | 17 | 15 (100%) | 2 (13%) |

|

|

|||

| HIV-infected, N (%) | 15 | 8 (53%) | 7 (47%) |

|

|

|||

| Proportion positive swabs in infants, median (range) | 30 | 0.47 (0.14, 0.75) | 0.19 (0.10, 0.66) |

|

|

|||

| Proportion positive swabs in secondary children, median (range) | 30 | 1 (0.19, 1) | 0.95 (0.08, 1) |

|

|

|||

| Infant oral sheddingb, median log10 DNA copies/swab (range) | 30 | 3.48 (2.47, 5.4) | 2.88 (2.53, 3.91) |

|

|

|||

| Secondary children oral shedding b, median log10 DNA copies/swab (range) | 30 | 3.59 (2.66, 5.52) | 3.21 (2.63, 4.86) |

|

|

|||

| Proportion of visits with oral contact reported in the previous week c, median (range) | 30 | 0 (0, 0.5) | 0.02 (0, 0.25) |

Exposures are summarized over time period from infant birth to maternal non-primary infection or end of follow-up, whichever comes first

Among positive swabs

Based on reported food or saliva sharing

Among the 15 mothers with non-primary infection, 8 were infected with HIV. The duration of oral shedding was not statistically different between women with HIV (median 25 weeks; range: 7–42) and without HIV infection (median 17 weeks; range 4–32; Wilcoxon rank-sum test p-value = 0.45). Maximum viral load was similar among HIV-infected (median 4.55 log10 copies/swab; range: 4.1 – 5.65) and –uninfected women (median 4.8 log10 copies/swab; range: 3.22 – 5.12; Wilcoxon rank-sum test p-value = 1).

Risk Factors for Maternal Non-Primary CMV Infection

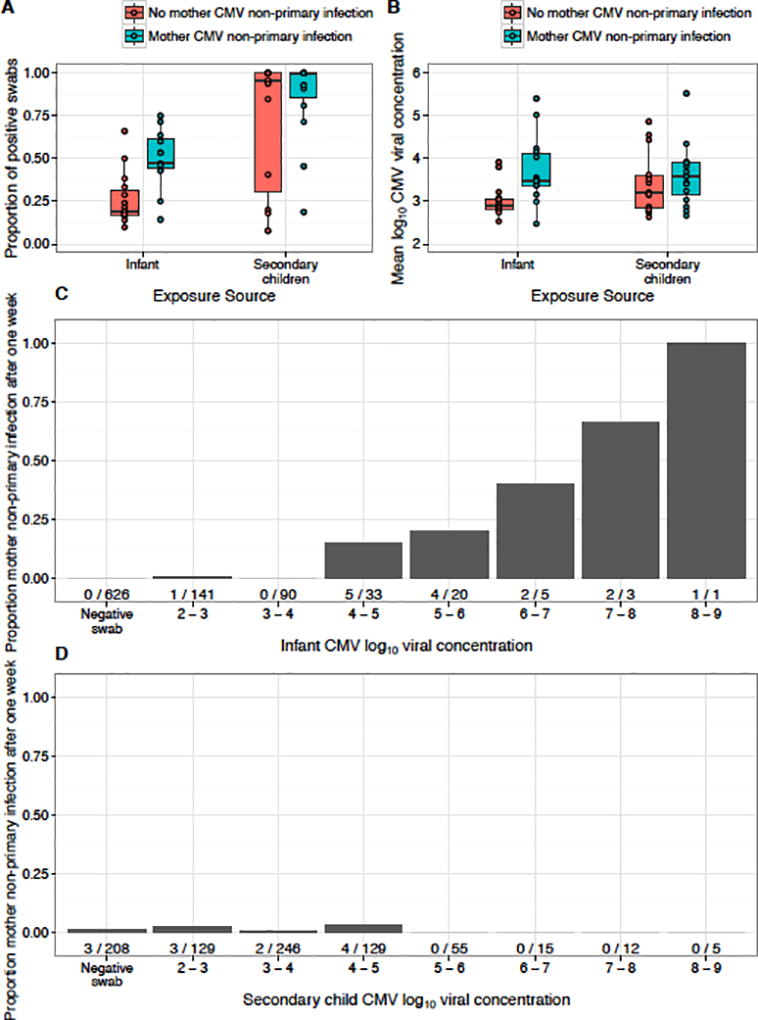

We first summarized risk factors from infant birth until maternal non-primary infection or the end of maternal follow-up (Table 1). Follow-up time was similar between mothers with and without non-primary infection. The proportion of positive swabs and mean saliva shedding in infants was higher in households where maternal non-primary infection was observed, a trend that was not pronounced in the secondary children (Table 1 and Fig. 1A–B). Reported oral contact behavior with infants and maternal HIV status were similar between households with and without maternal non-primary infection.

Figure 1. Household viral exposure and maternal non-primary infection.

A) Proportion of positive saliva swabs and B) Mean viral concentration among positive saliva swabs by infant and secondary child according to maternal non-primary infection. Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR) of the data; the whiskers extend to cover all data within 1.5 IQR of the first or third quartile. Individual data is represented by dots. C) Dose-response relationship between infant shedding and maternal non-primary infection the following the week. D) No relationship between secondary child shedding and maternal non-primary infection. Three mothers with non-primary infection had no secondary child shedding data from the prior week. The quantity of infant shedding was statistically associated with maternal non-primary infection (p-value <0.0001, Table 2). Number of maternal non-primary infections/positive swabs shown below each bar.

Next, we considered the timing of risk factors and the relationship between weekly exposures and risk of maternal non-primary infection in the subsequent week. The probability of maternal non-primary infection was positively correlated with the quantity of oral shedding by infants in the previous week (Fig. 1C), a pattern that was distinct from shedding by secondary children (Fig. 1D). We analyzed all risk factors in an adjusted Cox model with time-dependent variables for household shedding and reported oral contacts with infants (Table 2). Maternal non-primary infection was statistically significantly associated only with increasing infant shedding levels during the previous week (HR: 2.32 95% CI: 1.63, 3.31; p-value<0.0001), consistent with the observed dose-response relationship (Fig. 1C). Maternal HIV status was not significantly associated with the risk of non-primary CMV infection.

Table 2.

Risk factors for maternal CMV non-primary infection - results from multivariate analyses

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Predictors | Full model | Final model |

|

| ||

| Infant viral shedding the previous week (per log10 CMV DNA copies/swab) | 2.42 (1.63, 3.61)* | 2.32 (1.63, 3.31)* |

|

|

||

| Secondary child viral shedding the previous week (per log10 CMV DNA copies/swab) | 1.11 (0.78, 1.58) | |

|

|

||

| Oral contact reported in the previous week | 1.3 (0.14, 12.45) | |

|

|

||

| Maternal HIV infection | 0.84 (0.26, 2.69) | |

Statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Serologic Evidence of Maternal CMV Reinfection

Among the 21 mothers who had serum samples collected at the end of the follow-up period, 8 had evidence of CMV reinfection as defined by a change in type-specific serologic responses compared to the time of delivery. Serologic evidence of CMV reinfection was not significantly associated with maternal non-primary CMV infection: 2 of 9 women with non-primary infection had serologic evidence of reinfection compared with 6 of 12 of women who did not have a non-primary infection (Fisher’s exact test p-value = 0.37).

DISCUSSION

In our cohort of mother-infant pairs followed from the time of delivery, 50% of women were found to have a non-primary CMV infection. Maternal non-primary infection only occurred after infant primary CMV infection; no maternal non-primary infections were observed to occur prior to infant infection or among women whose infants did not acquire CMV. This temporal relationship is evident both in the graphical data and in the multivariate regression results, and suggests transmission from newly infected infants to their seropositive mothers. Our findings complicate the traditional paradigm of postnatal CMV transmission from mother to infant, by documenting maternal non-primary CMV infection that follows (rather than precedes) primary infection in the infant. However, this is similar to the observations in seronegative women acquiring primary CMV infections from their young children.

We acknowledge that other routes of maternal non-primary infection are possible. Mothers might have become reinfected with a different viral strain by a contact other than their own infant, though the consistent temporal association with infant infection undermines this explanation. Moreover, we failed to identify a relationship between oral CMV shedding by siblings and maternal non-primary infection. Another potential explanation of our findings is that the non-primary infections that we observed reflect reactivation rather than reinfection, although we think that it is unlikely that maternal reactivation should consistently occur after infant primary infection and in a statistically significant dose-dependent manner with infant CMV shedding (31).

Numerous studies have described that postnatal transmission of CMV occurs frequently from mothers to infants, which is often attributable to viral replication in breast milk that begins soon after delivery (21–25, 32–34). Indeed, in this infant cohort, we reported that primary CMV infection was most strongly associated with breastfeeding (11). Onset of CMV shedding in breast milk in previous studies was mainly within the first 2 weeks after delivery (32–34), while the onset of maternal non-primary infection in our study was 15 weeks after delivery. CMV shedding in breast milk preceding saliva could allow for the transmission of CMV to newborns before maternal non-primary infection. However, such a defined temporal order of shedding by compartment seems unlikely given that previous studies have shown no correlation between CMV shedding between breast milk and saliva (32, 33), and no maternal non-primary infections were observed prior to or in the absence of infant infection.

Transmission from an infant to its seropositive mother might be expected to occur when the infant was infected by a contact other than its mother, with a different antigenic strain. However, many infants are infected by their mothers; indeed, in this cohort and others breast milk was a major route of CMV transmission to infants (9–11). Furthermore, there was no evidence of reinfection with different antigenic strains in this cohort of mothers, based on strain-specific serology. Therefore, we speculate that, at least in some cases, mothers transmitted CMV to their infants, who then reinfected these mothers. This “ping-pong” effect might occur with back and forth transmission of the same viral strain(s), or might be facilitated by step-wise antigenic changes that occur as a result of extensive genetic diversity of CMV within each host and between anatomic compartments (i.e., breast milk and saliva or urine) (35–37). These changes likely would not be identified by CMV strain–specific antibody assay differences. Whatever the mechanism, the resulting dynamic of such highly permissive reinfection would have important implications for efforts to develop a vaccine to prevent CMV acquisition.

Strengths of our study include prospective weekly sampling of mothers and children to allow detailed temporal and quantitative associations regarding CMV transmission and acquisition. While the clear temporal dose response associations between infant and maternal oral shedding provide strong evidence for transmission from the infant to its mother, we were unable to definitively show that any given mother was the source of transmission to her infant, or that the mother’s non-primary infections were definitively attributable to exposure to their infant’s CMV. Since the CMV strain–specific antibody assay only measures antibodies against two epitopes (one on gH and the other on gB), it is estimated to detect only a small number of strain differences among the enormous variability of human CMV strain(38). Therefore, the absence of demonstration of strain difference by this assay is not evidence for reactivation. Comprehensive CMV genotyping of saliva and breast milk samples was not possible due to lack of adequate sample quantity or availability, but might help to determine the mechanism(s) by which maternal recurrence or oral shedding follows primary infection in infants if strains transmitted between infants and their mothers were genetically distinct. Other limitations include the lack of data about CMV shedding in breast milk and other potential CMV exposures, like fathers and school-aged children. Lastly, these results may not be generalizable to other populations, for example those with lower seroprevalence of CMV and other infections. As such, additional studies in other settings are needed.

In conclusion, this study describes clear temporal and dose-response associations between oral CMV shedding by infants with primary infection and non-primary infections suggestive of reinfection in their mothers. This novel finding raises intriguing biologic questions, including the barriers to reinfection with the same or closely related strains, and the impact of viral compartmentalization and intra-host diversity on transmission to seropositive individuals. Understanding the mechanisms by which CMV reinfects or reactivates in women has fundamental importance for preventing congenital CMV infection, whether through behavioral interventions or informing the development of an effective CMV vaccine. Thus, additional studies are needed to understand the impact of primary CMV infection in infants on non-primary infection in their mothers.

Supplementary Material

Risk factors for maternal CMV non-primary infection – results from multivariate analyses using complete case analysis

Non-primary maternal CMV infection and oral shedding following delivery and infant primary infection.

Each graph represents one mother-child pair. Infant CMV shedding is shown in blue. Seventeen infants had primary CMV infection; the time of infection is denoted with a vertical dotted line. Oral shedding by mothers with CMV non-primary infection is shown in black (n=15), while shedding by mothers that did not meet criteria for non-primary infection is shown in gray (n = 15). Solid vertical lines indicate the timing of maternal recurrence. No maternal shedding episodes were observed in mothers without an infected infant, and 2 mothers with a postnatally infected infant did not have a recurrent infection.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support/funding: This work was supported by grants from the NIH – Roadmap KL2 Clinical Scholar Training Program KL2-RR025015-01 (SG), University of Washington Center for AIDS Research New Investigator Award P30-AI027757 (SG), P01-AI 030731 (LC, AW, SS, JTS, MLH); R01-CA138165 (CC), and P30-CA015704 (CC and LC) – and by a Child & Family Research Institute Salary Award (SG).

References

- 1.Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:355–363. doi: 10.1002/rmv.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larke RP, Wheatley E, Saigal S, Chernesky MA. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in an urban Canadian community. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:647–653. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.5.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vries JJ, van Zwet EW, Dekker FW, Kroes AC, Verkerk PH, Vossen AC. The apparent paradox of maternal seropositivity as a risk factor for congenital cytomegalovirus infection: a population-based prediction model. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23:241–249. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boppana SB, Fowler KB, Britt WJ, Stagno S, Pass RF. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection in infants born to mothers with preexisting immunity to cytomegalovirus. Pediatrics. 1999;104:55–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1094–1097. doi: 10.1086/339329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boppana SB, Rivera LB, Fowler KB, Mach M, Britt WJ. Intrauterine transmission of cytomegalovirus to infants of women with preconceptional immunity. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1366–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross SA, Arora N, Novak Z, Fowler KB, Britt WJ, Boppana SB. Cytomegalovirus reinfections in healthy seroimmune women. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:386–389. doi: 10.1086/649903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto AY, Mussi-Pinhata MM, Boppana SB, et al. Human cytomegalovirus reinfection is associated with intrauterine transmission in a highly cytomegalovirus-immune maternal population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:297, e291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karachaliou M, Waterboer T, Casabonne D, et al. The Natural History of Human Polyomaviruses and Herpesviruses in Early Life-The Rhea Birth Cohort in Greece. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:671–679. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staras SA, Flanders WD, Dollard SC, Pass RF, McGowan JE, Jr, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and childhood sources of infection: A population-based study among pre-adolescents in the United States. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gantt S, Orem J, Krantz EM, et al. Prospective Characterization of the Risk Factors for Transmission and Symptoms of Primary Human Herpesvirus Infections Among Ugandan Infants. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lidehall AK, Engman ML, Sund F, et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses in infants and children. Scand J Immunol. 2013;77:135–143. doi: 10.1111/sji.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon MJ, Stowell JD, Clark R, et al. Repeated measures study of weekly and daily cytomegalovirus shedding patterns in saliva and urine of healthy cytomegalovirus-seropositive children. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14:569. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler KB, Pass RF. Risk factors for congenital cytomegalovirus infection in the offspring of young women: exposure to young children and recent onset of sexual activity. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e286–292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pass RF, Little EA, Stagno S, Britt WJ, Alford CA. Young children as a probable source of maternal and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1366–1370. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall BC, Adler SP. The frequency of pregnancy and exposure to cytomegalovirus infections among women with a young child in day care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:163, e161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Franca TR, de Albuquerque Tavares Carvalho A, Gomes VB, Gueiros LA, Porter SR, Leao JC. Salivary shedding of Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus in people infected or not by human immunodeficiency virus 1. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:659–664. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ling PD, Lednicky JA, Keitel WA, et al. The dynamics of herpesvirus and polyomavirus reactivation and shedding in healthy adults: a 14-month longitudinal study. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1571–1580. doi: 10.1086/374739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller CS, Berger JR, Mootoor Y, Avdiushko SA, Zhu H, Kryscio RJ. High prevalence of multiple human herpesviruses in saliva from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2409–2415. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00256-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanghellini F, Boppana SB, Emery VC, Griffiths PD, Pass RF. Asymptomatic primary cytomegalovirus infection: virologic and immunologic features. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:702–707. doi: 10.1086/314939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asanuma H, Numazaki K, Nagata N, Hotsubo T, Horino K, Chiba S. Role of milk whey in the transmission of human cytomegalovirus infection by breast milk. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:201–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamprecht K, Maschmann J, Vochem M, Dietz K, Speer CP, Jahn G. Epidemiology of transmission of cytomegalovirus from mother to preterm infant by breastfeeding. Lancet. 2001;357:513–518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hotsubo T, Nagata N, Shimada M, Yoshida K, Fujinaga K, Chiba S. Detection of human cytomegalovirus DNA in breast milk by means of polymerase chain reaction. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:809–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yasuda A, Kimura H, Hayakawa M, et al. Evaluation of cytomegalovirus infections transmitted via breast milk in preterm infants with a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1333–1336. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slyker J, Farquhar C, Atkinson C, et al. Compartmentalized cytomegalovirus replication and transmission in the setting of maternal HIV-1 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:564–572. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer BT, Krantz EM, Swan D, et al. Transient Oral Human Cytomegalovirus Infections Indicate Inefficient Viral Spread from Very Few Initially Infected Cells. Journal of virology. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00380-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stowell JD, Mask K, Amin M, et al. Cross-sectional study of cytomegalovirus shedding and immunological markers among seropositive children and their mothers. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0568-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen PK, Gill RD. Cox's Regression Model for Counting Processes: A Large Sample Study [Google Scholar]

- 29.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer BT, Matrajt L, Casper C, et al. Dynamics of Persistent Oral Cytomegalovirus Shedding During Primary Infection in Ugandan Infants. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1735–1743. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fedak KM, Bernal A, Capshaw ZA, Gross S. Applying the Bradford Hill criteria in the 21st century: how data integration has changed causal inference in molecular epidemiology. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2015;12:14. doi: 10.1186/s12982-015-0037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dworsky M, Yow M, Stagno S, Pass RF, Alford C. Cytomegalovirus infection of breast milk and transmission in infancy. Pediatrics. 1983;72:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vochem M, Hamprecht K, Jahn G, Speer CP. Transmission of cytomegalovirus to preterm infants through breast milk. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:53–58. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Strate BW, Harmsen MC, Schafer P, et al. Viral load in breast milk correlates with transmission of human cytomegalovirus to preterm neonates, but lactoferrin concentrations do not. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:818–821. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.4.818-821.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinzger C, Grefte A, Plachter B, Gouw AS, The TH, Jahn G. Fibroblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells are major targets of human cytomegalovirus infection in lung and gastrointestinal tissues. J Gen Virol. 1995;76(Pt 4):741–750. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-4-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renzette N, Pokalyuk C, Gibson L, et al. Limits and patterns of cytomegalovirus genomic diversity in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E4120–4128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501880112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renzette N, Gibson L, Bhattacharjee B, et al. Rapid intrahost evolution of human cytomegalovirus is shaped by demography and positive selection. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003735. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lassalle F, Depledge DP, Reeves MB, et al. Islands of linkage in an ocean of pervasive recombination reveals two-speed evolution of human cytomegalovirus genomes. Virus Evolution. 2016;2:vew017–vew017. doi: 10.1093/ve/vew017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Risk factors for maternal CMV non-primary infection – results from multivariate analyses using complete case analysis

Non-primary maternal CMV infection and oral shedding following delivery and infant primary infection.

Each graph represents one mother-child pair. Infant CMV shedding is shown in blue. Seventeen infants had primary CMV infection; the time of infection is denoted with a vertical dotted line. Oral shedding by mothers with CMV non-primary infection is shown in black (n=15), while shedding by mothers that did not meet criteria for non-primary infection is shown in gray (n = 15). Solid vertical lines indicate the timing of maternal recurrence. No maternal shedding episodes were observed in mothers without an infected infant, and 2 mothers with a postnatally infected infant did not have a recurrent infection.