Abstract

Schwannomas are benign tumors arising from schwann cells in peripheral, cranial, and autonomic nerve sheaths. Approximately half of all cases of schwannomas are observed in the head and neck region. In this study, a 71-year-old male patient presenting with a stiff mobile mass in the left supraclavicular region and diagnosed as a schwannoma after total excision was presented.

Keywords: Schwannoma, neck, supraclavicular region, benign tumor

Introduction

Schwannoma was first described by Verocay in 1908 and named as “neuroma,” later in 1935 Stout suggested the name “neurilemmoma” because the tumor arises from nerve sheath and schwann cells (1). Schwannomas can originate from a peripheral, cranial or autonomic nerve in any part of the body and constitute about 5% of all soft tissue tumors. In about 25–45% of the cases schwannomas are seen in the head and neck region. It can present in all ages but is more commonly seen between ages 20 to 50 years (2).

The most common cranial nerve in the body that schwannomas are seen to involve is the vestibular branch of the acoustic nerve, and cases localized in the neck region are most commonly seen in the parapharyngeal space. Schwannomas in the neck region often arise from the vagus nerve.

In this article we present the case of a 71-year-old male patient who presented with a firm mobile mass in the supraclavicular region and was diagnosed with schwannoma following total excision and histopathological examination.

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old male patient presented to our clinic with a large swelling on his left neck that he had noticed six months earlier. The mass had grown in the course of these six months. The patient had no additional complaints. In physical examination, a firm, mobile and painless mass of about 6×4cm was identified in the supraclavicular region of the neck. Endoscopic examination did not show any pathologic lesions in the nasopharynx, hypopharynx or larynx.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck was reported as images of conglomerate LAPs (cystic metastatic LAP?) separated by septa in left supraclavicular region, the largest of which is 6×4.5cm on axial section, and exhibit iso- to hypointense enhancement on T1 and hyperintense enhancement on T2 (Figures 1, 2). Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was done. FNAB result was reported as cytologic sample of non-diagnostic character.

Figure 1.

Preoperative MRI view of patient

Figure 2.

Preoperative MRI view of patient

Supraclavicular mass excision was performed under general anesthesia. Conglomerate, interconnected masses of which the largest was 4×3cm were observed during the operation. The mass was encapsulated, could be easily dissected from the adjacent tissue, and extended to the apex of the lung. The mass was removed in whole together with its capsule and all the cervical structures were preserved (Figure 3). Neurologic deficit was not seen in the postoperative period. Histopathological examination of the surgical sample revealed a multi-cystic schwannoma (Figures 4, 5). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the scientific publication of his case.

Figure 3.

Macroscopic view of the mass

Figure 4.

Diffuse staining with S-100 in schwannoma (immunoperoxidase X200)

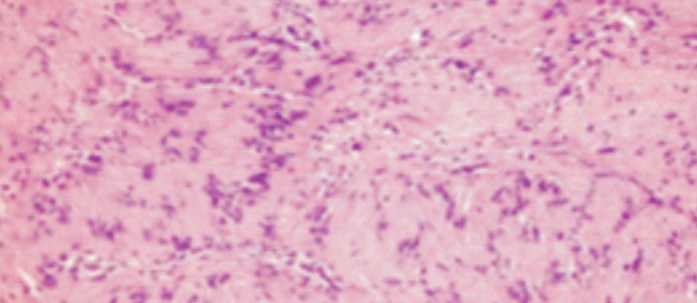

Figure 5.

Palisading cells in Antoni A zone and loosely meshed cells in Antoni B zone (HE X200)

Discussion

Neurogenic tumors in the head and neck region are rare. Neurogenic tumors seen in this region are neurofibroma, schwannoma, neurogenic nevus, granular cell myoblastoma, neurogenic sarcoma, malignant melanoma and neuroepithelioma.

About 25–45% of the schwannomas settle in the head and neck region. These tumors can arise from any of the cranial, peripheral or autonomic nerves except the optic nerve. Schwannomas constitute less than 1% of the tumors seen in the head and neck region. Studies have found no significant differences between genders with respect to predominance. The probability of malignant transformation of schwannomas is around 8–10%. They can be seen in all age groups, however, are more common in the third and fourth decades of life (3). Our patient’s age was 71, considerably higher than the mean age reported in the literature.

Schwannomas are grouped as medial and lateral in terms of their localization and the nerve they arise from. Parapharyngeal schwannomas comprise the medial group. Cases which originate here arise from the last four cranial nerves, namely, the n.glossopharyngeus, n.vagus, n.accessorius, and n.hypoglossus. Schwannomas that originate from the cervical and brachial plexus comprise the lateral group (4). In our case the tumor was of the lateral group, localized to the supraclavicular region and originating from the cervical or brachial plexus.

Schwannomas often settle in the parapharyngeal space of the neck and mostly arise from the 10th cranial nerve. Schwannomas that settle in this region are usually encountered as medial neck masses, and schwannomas that originate from the cervical or brachial plexus as lateral neck masses (5). Schwannomas do not present clinically for a long time. The most frequently encountered symptom is a slow growing mass. Neurologic findings and pain are rarely seen symptoms. In some advanced cases schwannoma can exert pressure on the adjacent anatomic structures, causing symptoms such as coughing, dysphagia, cranial nerve paralysis, Horner’s syndrome and hearing loss (3). Our patient had a painless mass on his left neck that had been growing for six months. And there were no symptoms of pressure or signs of neurologic deficit.

Tumors originating from the brachial plexus are rarely seen and comprise less than 5% of the tumors in the upper extremities. In a study Kehoe et al. (6) report that 36% of the tumors originating from the brachial plexus localize to the supraclavicular, and 64% to the infraclavicular region.

Langner et al. (7) report that of their 21 schwannoma cases five (23.8%) originated from the brachial plexus, three (14.2%) from the 10th cranial nerve, four (19%) from the sympathetic plexus, and three (14.2%) from other nerves. The authors report that in six cases (28.4%) of the same series the nerve from which the tumor originated could not be found. In our case, the tumor originated from the brachial plexus.

Schwannomas are encapsulated, well-circumscribed tumors and histopathologically show a biphasic pattern. Antoni A pattern is composed of compact spindle cells with elongated nucleus, arranged in fascicles and cords. Antoni B pattern is composed of hypocellular zones of fewer cells with loose myxoid matrix. Verocay bodies—oval acellular zones surrounded by parallel nuclear palisades—can be seen. Immunohistochemical staining is positive for S-100 and vimentin. Schwann cells stain positive for CD68 and GFAP. Likewise, S-100 and vimentin were positive in the presented case (8).

Carotid body tumors, lymphadenopathy, thyroid nodules or thyroid cysts, branchial cysts, teratoma, dermoid cysts, lipomas, metastatic masses and neurofibromas should be considered in differential diagnosis (9). Localization, radiological examination and FNAB are used for differential diagnosis. Preoperative radiological examination can provide useful information for diagnosing schwannoma. In computed tomography schwannomas appear well-circumscribed and slightly hyperintense. In MRI they appear slightly hypointense or isointense on T1 sequences and hyperintense on T2 sequences. Most schwannoma cases exhibit heterogeneous enhancement after contrast medium is given. Cystic degeneration zones are usually seen if schwannoma has reached large dimensions. Although the diagnostic value of FNAB is insufficient, it can be beneficial when evaluated together with radiological examination results (10). In our case, the atypical localization of the mass seen in preoperative radiological examination and interpretation of the cystic degeneration zones as conglomerates led the diagnosis away from schwannoma. It should nevertheless be considered that cystic degeneration zones can be seen in large-size schwannomas.

The preferred treatment in schwannoma is total surgical excision of the mass. Despite the risk of recurrence, it is important to preserve as much as possible the nerve from which the tumor has arisen. Valentino et al. (3) report a success rate of 56% for functional surgery. Intraoperative electrophysiological monitorization can be useful in terms of reducing complication rates. Recurrence after total excision is rare in schwannoma cases (4). In our case, the mass was totally excised, and since encapsulated, attachment to adjacent tissue structures was minimal, which allowed for easier dissection. Given the close proximity of the mass to the apex of the lung, there were risks of complications such as large vessel injury, pneumothorax and lung contusion during dissection. Careful dissection eliminated all of these complications. Neurologic deficit was not observed in the postoperative period.

Conclusion

In patients over 40 years of age systemic examination should necessarily be performed with the assumption that masses in the supraclavicular region are secondary symptoms of a primary disease. Albeit rare, neurogenic tumors like schwannomas should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of firm, well-circumscribed, painless and mobile masses. It should also be kept in mind that cystic degeneration zones may be present in schwannomas that reach large dimensions, as was the case in our patient, and that these cystic degeneration zones can be confused with conglomerates in preoperative radiological examinations.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the 13th Turkish Rhinology, 5th Otology-Neurotology and 1ST Head and Neck Surgery Congress, May 4–7, 2017, Antalya, Turkey.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - E.K., O.E., İ.Ö., İ.H.Ö.; Design - E.K., O.E., İ.Ö., İ.H.Ö.; Supervision - E.K., O.E., İ.H.Ö., İ.Ö.; Resource - E.K., O.E., İ.H.Ö.; Materials - E.K., O.E., İ.H.Ö.; Data Collection and/or Processing - E.K., O.E., İ.Ö.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - E.K., O.E., İ.H.Ö.; Literature Search - E.K., O.E., İ.H.Ö.; Writing - E.K., O.E., İ.Ö.; Critical Reviews - E.K., O.E., İ.H.Ö.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Erbek HS, Erbek SS, Tosun E, Çakmak Ö. Intraparotid facial nerve schwannoma: a case report. KBB ve BBC Dergisi. 2005;13:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber AL, Montandon C, Robson CD. Neurogenic tumors of the neck. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:1077–90. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70222-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valentino J, Boggess MA, Ellis JL, Hester TO, Jones RO. Expected neurologic outcomes for surgical treatment of cervical neurilemmomas. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1009–13. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199807000-00011. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley N, Bowerman JE. Parapharyngeal neurilemmomas. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;27:139–46. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(89)90061-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-4356(89)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capparpur C, Büyüklü F, Çakmak İ, Öztop L, Özlüoğlu LN. Schwannoma arising from cervical sympathetic chain: a case report. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;40:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kehoe NJ, Reid RP, Semple JC. Solitary benign peripheral-nerve tumours: review of 32 years’ experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:497–500. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.77B3.7744945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langner E, Del Negro A, Akashi HK, Araújo PP, Tincani AJ, Martins AS. Schwannomas in the head and neck: retrospective analysis of the 21 patients and review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med J. 2007;124:220–2. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802007000400005. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-31802007000400005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miettinen M. Diagnostic Soft Tissue Pathology. 1st edn. Philadelphia: 2003. Nevre sheath tumors; pp. 353–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biswas D, Marnane CN, Mal R, Baldwin D. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas-a 10-year review. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.01.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Cai C, Wang S, Liu H, Ye Y, Chen X. Extracranial head and neck schwannomas: a clinical analysis of 33 patients. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:278–81. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000249929.60975.a7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000249929.60975.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]