Abstract

Aim

The aim of this official guideline published by the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) and coordinated with the German Society of Urology (DGU) and the German Society of Reproductive Medicine (DGRM) is to provide consensus-based recommendations, obtained by evaluating the relevant literature, on counseling and fertility preservation for prepubertal girls and boys as well as patients of reproductive age. Statements and recommendations for girls and women are presented below. Statements or recommendations for boys and men are not the focus of this guideline.

Methods

This S2k guideline was developed at the suggestion of the guideline commission of the DGGG, DGU and DGRM and represents the structured consensus of representative members from various professional associations (n = 40).

Recommendations

The guideline provides recommendations on counseling and fertility preservation for women and girls which take account of the patientʼs personal circumstances, the planned oncologic therapy and the individual risk profile as well as the preferred approach for selected tumor entities.

Key words: fertility preservation, oncologic diseases, guideline

Zusammenfassung

Ziel Das Ziel dieser offiziellen Leitlinie, die von der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG) publiziert und zusammen mit der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Urologie (DGU) sowie Deutschen Gesellschaft für Reproduktionsmedizin (DGRM) koordiniert wurde, ist es, durch die Evaluation der relevanten Literatur konsensbasierte Handlungsempfehlungen für die Beratung und den Einsatz von fertilitätserhaltenden Maßnahmen bei präpubertären Mädchen und Jungen sowie für Patienten/-innen im reproduktiven Alter zu geben. Im Folgendem werden die Statements und Empfehlungen für Mädchen und Frauen dargestellt. Die Statements und Empfehlungen für Jungen und Männer sind nicht Inhalt dieser Publikation.

Methoden Diese S2k-Leitlinie wurde durch einen strukturierten Konsens von repräsentativen Mitgliedern verschiedener Fachgesellschaften (n = 40) im Auftrag der Leitlinienkommission der DGGG, DGU und DGRM entwickelt.

Empfehlungen Es werden Empfehlungen zur Beratung und dem Einsatz von fertilitätserhaltenden Maßnahmen bei Patientinnen unter Berücksichtigung der Lebensumstände, der geplanten onkologischen Therapie und des individuellen Risikoprofils dargestellt sowie über das Vorgehen bei ausgewählten Tumorentitäten.

Schlüsselwörter: Fertilitätserhalt, onkologische Erkrankungen, Leitlinie

I Guideline Information

Information on the guidelines program of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG is provided at the end of the article.

Citation format

Fertility Preservation for Patients with Malignant Disease. Guideline of the DGGG, DGU and DGRM (S2k-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/082, November 2017) – Recommendations and Statements for Girls and Women. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2018; 78: 567–584

Guideline documents

The complete long version of the guideline in German, a PDF slideshow for PowerPoint presentations and a summary of the conflicts of interest of all authors are available on the homepage of the AWMF: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/015-082.html

Guideline authors

The following professional and scientific societies/working groups/organizations/associations stated the interest in contributing to the compilation of the guideline text and participating in the consensus conference and nominated representatives to attend the consensus conference ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 Authors and representativity of the guideline group: participation of the target user group.

| Author Mandate holder |

DGGG working group/AWMF/non-AWMF professional society/organization/association |

|---|---|

| Dr. med. Magdalena Balcerek | Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology [Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie e. V.] (GPOH) |

| Ramona Beck | Self-help Group for Women after Cancer [Frauenselbsthilfe nach Krebs e. V.] |

| Prof. Dr. med. Matthias W. Beckmann | Expert |

| Dr. med. Karolin Behringer | Working Group for Internal Oncology [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie] (AIO); German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämatologie und Medizinische Onkologie e. V.] (DGHO) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Anja Borgmann-Sta[udt | German Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin e. V.] (DGKJ); Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology [Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie e. V.] (GPOH) |

| Dr. rer. nat. Dunja M. Baston-Büst | German Society of Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Reproduktionsmedizin e. V.] (DGRM) |

| Dr. med. Wolfgang Cremer | Professional Association of Gynecologists [Berufsverband der Frauenärzte e. V.] (BVF) |

| Dr. med. Christian Denzer | German Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderendokrinologie und -diabetologie e. V.] (DGKED) |

| PD Dr. med. Thorsten Diemer | German Society of Urology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie e. V.] (DGU) |

| Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Ralf Dittrich[ | German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e. V.] (DGGG) |

| Dipl.-Psych. Dr. phil. Almut Dorn | German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapie and Psychosomatics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e. V.] (DGPPN) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Tanja Fehm | Gynecologic Oncology Working Group [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie e. V.] (AGO) |

| Dr. med. Rüdiger Gaase | Professional Association of Gynecologists (BVF) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Ariane Germeyer | German Society for Gynecologic Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin e. V.] (DGGEF) |

| Dr. rer. med. Kristina Geue | Psycho-Oncology Working Group [Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Psychoonkologie e. V.] (PSO) |

| PD Dr. med. Pirus Ghadjar | German Society of Radio-Oncology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Radioonkologie e. V.] (DEGRO) |

| Dr. med. Maren Goeckenjan | German Society for Gynecologic Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine (DGGEF) |

| Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Martin Götte | German Society for Endocrinology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Endokrinologie e. V.] (DGE) |

| Dr. med. Dagmar Guth | Professional Association of Practice-based Gynecologic Oncologists in Germany [Berufsverband Niedergelassener Gynäkologischer Onkologen in Deutschland e. V.] (BNGO) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Berthold P. Hauffa | German Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (DGKED) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Ute Hehr | German Society of Human Genetics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Humangenetik e. V.] (GfH) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Franc Hetzer | German Society of Coloproctology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Koloproktologie e. V.] (DGK) |

| Dr. rer. nat. Jens Hirchenhain | German Society of Human Reproductive Biology [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Reproduktionsbiologie des Menschen e. V.] (AGRBM) |

| Dr. med. Wilfried Hoffmann | Working Group for Supportive Care in Oncology, Rehabilitation and Social Medicine [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Supportive Maßnahmen in der Onkologie, Rehabilitation und Sozialmedizin e. V.] (ASORS) |

| Dipl.-Psych. Beate Hornemann | Psycho-Oncology Working Group (PSO) |

| Dr. med. Andreas Jantke | Federal Association of Reproductive Medicine Centers in Germany [Bundesverband Reproduktionsmedizinischer Zentren Deutschland e. V.] (BRZ) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Heribert Kentenich | German Society of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe e. V.] (DGPFG) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Frank-Michael Köhn | German Society of Andrology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Andrologie e. V.] (DGA); German Society for Sexual Medicine, Sexual Therapy and Sexual Science [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sexualmedizin, Sexualtherapie und Sexualwissenschaft e. V.] (DGSMTW) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Ludwig Kiesel | German Society for Endocrinology (DGE) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Sabine Kliesch | German Society of Urology (DGU); Working Group on Urologic Oncology [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Urologische Onkologie e. V.] (AUO) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Matthias Korell | Gynecologic Endoscopy Working Group [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Endoskopie e. V.] (AGE) |

| Prof. Prim. Dr. Sigurd Lax | German Society of Pathology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pathologie e. V.] (DGP); Federal Association of German Pathologists [Bundesverband Deutscher Pathologen e.V] (BVDP) |

| Dr. rer. nat. Jana Liebenthron | FertiPROTEKT Network |

| Dr. med. Laura Lotz | Guidelines secretary |

| Prof. Dr. med. Michael Lux | German Society for Senology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Senologie e. V.] (DGS) |

| Dr. med. Julia Meißner | Internal Oncology Working Group [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie] (AIO); German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämatologie und Medizinische Onkologie e. V.] (DGHO) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Oliver Micke | AG PRIo of the DKG [German Cancer Society] |

| Najib Nassar | Federal Association of Reproductive Medicine Centers in Germany (BRZ) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Frank Nawroth | FertiPROTEKT Network |

| PD Dr. rer. nat. Verena Nordhoff | Human Reproductive Biology Working Group [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Reproduktionsbiologie des Menschen e. V.] (AGRBM) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Falk Ochsendorf | German Dermatology Society [Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft e. V.] (DDG) |

| PD Dr. Patricia G. Oppelt | Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Working Group [Arbeitsgemeinschaft Kinder- und Jugendgynäkologie e. V.] (AG) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Jörg Pelz | German Society for General and Visceral Surgery [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie e. V.] (DGAV) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Beate Rau | German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV) |

| PD Dr. med. Nicole Reisch | German Society of Internal Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin e. V.] (DGIM) |

| Dr. med. Dorothea Riesenbeck | Working Group for Supportive Care in Oncology, Rehabilitation and Social Medicine (ASORS); German Society of Radio-Oncology (DEGRO) |

| Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Stefan Schlatt | Clinical Research Group for Reproductive Medicine [Klinische Forschergruppe für Reproduktionsmedizin e. V.] |

| PD Dr. Andreas Schüring | German Society of Reproductive Medicine (DGRM) |

| Dr. med. Roxana Schwab | Expert |

| Dip.-Psych. Annekathrin Sender | Expert |

| PD Dr. med. Friederike Siedentopf | German Society of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology (DGPFG) |

| Dr. phil. Petra Thorn | Infertility Counseling Network Germany [Beratungsnetzwerk Kinderwunsch Deutschland e. V.] (BKiD) |

| Dr. med. Steffen Wagner | Professional Association of Practice-based Gynecologic Oncologists in Germany (BNGO) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Ludwig Wildt | German Society for Endocrinology (DGE); Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [Österreichische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e. V.] (OEGGG) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Pauline Wimberger | Expert |

| PD Dr. sc. hum. Tewes Wischmann, Dipl.-Psych. | Infertility Counseling Network Germany (BKiD) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Michael von Wolff | Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe] (SGGG) |

Abbreviations

- ABVD

doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine

- AC

doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AMH

anti-Müllerian hormone

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- ART

assisted reproductive technologies

- BEACOPP

bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone

- BOT

borderline tumor

- CAF

cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, fluorouracil

- CEF

cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, 5-flourouracil

- ChlVPP/EVA hybrid COPP

chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, prednisone/ etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin

- CHOP

cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone

- CI

confidence interval

- CMF

cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil

- CML

chronic myelogenous leukemia

- CVP

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EC

epirubicin, cyclophosphamide

- ESD

effective sterilizing dose

- FOLFOX

folinic acid (leucovorin), 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin

- GnRH

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- GnRHa

gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist

- Gy

Gray

- HL

Hodgkinʼs lymphoma

- MVPP

mustine, vinblastine, procarbazine, prednisolone

- NHL

non-Hodgkinʼs lymphoma

- OR

odds ratio

- POI

premature ovarian insufficiency

- RR

relative risk

- SCT

stem cell transplantation

- TAC

paclitaxel (taxol), doxorubicin (adriamycin), cyclophosphamide

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitors

II Guideline Application

Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of this guideline is to provide recommendations for action with regard to counseling and fertility preservation for prepubertal girls and women of reproductive age with oncologic disease which take account of the patientsʼ personal circumstances and risk profile. The aim is to increase the rate of successful pregnancies after completing oncologic therapy and to improve the patientsʼ quality of life.

Targeted areas of patient care

Outpatient care

Inpatient care

Semi-residential care

Target patient groups

The guideline is aimed at all prepubertal girls and patients of reproductive age who require gonadotoxic treatment for malignant disease.

Target user group/target audience

This guideline is aimed at all physicians and medical professionals involved in the care of patients who require gonadotoxic therapy.

The principal among these are: gynecologists, reproductive medicine physicians, andrologists, urologists, oncologists, radio-oncologists, general practitioners, pediatricians, pathologists, psycho-oncologists.

Adoption of the guideline and period of validity

This guideline is valid from November 1, 2017 to October 31, 2020. Because of the contents of the guideline, this period of validity is only an estimate. If there are important changes to the evidence, then amendments to the guideline will be published before the period of validity has expired, once the new evidence has been carefully reviewed in accordance with the methodology of the AWMF.

III Methodology

Basic principles

The methodology used to prepare this guideline is determined by the class to which the guideline is assigned. The AWMF Guidance Manual (version 1.0) has set out the respective rules and regulations for the classification of guidelines. Guidelines are differentiated into lowest (S1), intermediate (S2) and highest (S3) class. The lowest class is defined as a summary of recommendations for action compiled by a non-representative group of experts. In 2004 the S2 class was divided into two subclasses: a systematic evidence-based subclass (S2e) and a structural consensus-based subclass (S2k). The highest S3 class combines both approaches.

This guideline is classified as: S2k

Grading of recommendations

While the description of the quality of the evidence (strength of evidence) serves as an indication for the robustness of the publicized data and therefore expresses the extent of certainty/uncertainty about the data, the classification of the level of recommendation reflects the result of weighing up the desirable and adverse consequences of alternative approaches.

A grading of the evidence and of the recommendations is not envisaged for S2k-level guidelines. The level of recommendation is differentiated by syntax, not by symbols. The syntax used to grade the level of recommendation is described in the background text ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Grading of recommendations.

| Description of level of recommendation | Syntax |

|---|---|

| Strong recommendation, highly binding | must/must not |

| Recommendation, moderately binding | should/should not |

| Open recommendation, not binding | may/may not |

Statements

Expert statements included in this guideline which are not recommendations for action but simple statements of fact are referred to as Statements. It is not possible to provide a level of evidence for these statements.

Achieving consensus and strength of consensus

As part of structured consensus-based decision-making (S2k/S3 level), authorized participants present at consensus sessions vote on draft Statements and Recommendations. Discussions at the sessions can lead to significant changes in the wording of Statements and Recommendations. The extent of agreement, which depends on the number of participants, is then determined at the end of the session ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Classification on extent of agreement following consensus-based decision-making.

| Symbol | Strength of consensus | Extent of agreement in percent |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | Strong consensus | > 95% of participants agree |

| ++ | Consensus | > 75 – 95% of participants agree |

| + | Majority agreement | > 50 – 75% of participants agree |

| – | No consensus | < 50% of participants agree |

Expert consensus

As the name implies, this term refers to consensus decisions taken with regard to specific Recommendations/Statements without a previous systematic search of the literature (S2k) or when evidence is lacking (S2e/S3). The term “expert consensus” (EC) used here is synonymous with terms used in other guidelines such as “good clinical practice” (GCP) or “clinical consensus point” (CCP). The strength of the recommendation is graded as previously described in the chapter “Grading of recommendations”; the strength of consensus is only indicated semantically (“must”/“must not” or “should”/“should not” or “may”/“may not”) with no use of symbols.

IV Guideline

Statements and Recommendations on fertility preservation for girls and women with oncologic disease are presented below.

1 Introduction to Fertility Protection for Persons Diagnosed with Oncologic Disease

1.2 Importance and problems of fertility protection for persons diagnosed with cancer

Oncologic therapies often lead to partial or complete impairment of gonadal function in both men and women along with the potential loss of germ cells. Faced by the impact of a life-threatening disease, subsequent infertility may appear to be a minor issue for non-affected persons. For many of the patients themselves, however, premature ovarian insufficiency or sterility is a very stressful situation for both the affected patient and their partner 2 , 3 .

| Consensus-based Recommendation 1.R1 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Assessing the risk of possible infertility and the choice of method(s) for fertility preservation must be done by an interdisciplinary panel and discussed with the patient in good time before the start of oncologic therapy. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 1.S1 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Counseling about concepts to preserve fertility must be an integral part of every patientʼs oncologic treatment and must take account of the patientʼs personal circumstances, recommended oncologic therapy and individual risk profile. | |

2 Causes of Gonadal Toxicity in Women

2.1 Gonadal damage from surgery

Depending on the extent of radical surgery, gynecologic oncologic disease can result in sterility following complete or partial removal of the uterus and/or ovaries. Fertility-preserving surgery for various tumor entities is discussed in Chapter 4.1 of the long version of the guideline.

2.2 Gonadal toxicity from chemotherapy

The gonadal toxicity of individual chemotherapeutic drugs depends on their mechanism of action, the administered dose, the duration of therapy, the way in which therapy is administered, concomitant therapeutic treatments such as simultaneous radiotherapy or ovary-removal surgery, the patientʼs age, and the patientʼs individual disposition ( Table 4 ).

| Risk | Regimen/Substance |

|---|---|

| High risk (> 80% risk of permanent amenorrhea) |

|

| Intermediate risk (40 – 60% risk of permanent amenorrhea) |

|

| Low risk (< 20% risk of permanent amenorrhea) |

|

| Very low or no risk of permanent amenorrhea |

|

| Consensus-based Statement 2.R2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women scheduled to receive a potentially gonadotoxic dose of chemotherapeutic drugs must be informed about the risk of ovarian insufficiency and about methods to preserve fertility. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 2.S3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The negative impact of the gonadal toxicity of chemotherapies increases with patient age. Not all patients in a specific age group who receive therapy according to a defined regimen will develop the same fertility disorder. | |

2.3 Gonadal toxicity from radiotherapy

2.3.1 Ovarian radiation damage

( Table 5 )

Table 5 Radiotoxicity and ovarian insufficiency (modified from 6 ).

| Effective sterilizing dose (ESD) | Ovarian radiation dose (Gy) |

|---|---|

| No relevant effect | 0.6 |

| No relevant effect at < 40 years | 1.5 |

| 0 years | 20.3 |

| 10 years | 18.4 |

| 20 years | 16.5 |

| 30 years | 14.3 |

| 40 years | 6 |

| Consensus-based Statement 2.S4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Whether women develop ovarian insufficiency depends on the radiation dose, the age when the patient was exposed to radiation and the volume of irradiated ovarian tissue. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.R3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients who are scheduled to receive radiotherapy which will also irradiate the anatomical area of the ovaries must be informed about the risk of ovarian damage and must be made aware of methods which could preserve their fertility. | |

2.3.2 Tubal radiation damage

Radiogenic tubal changes can lead to a loss of function, resulting in limited fertility. Extrauterine pregnancies and their associated subsequent complications can occur, even if ovarian and uterine function have been preserved. Nothing is known about tubal tolerance doses.

2.3.3 Uterine radiation damage

In contrast to chemotherapy, radiotherapy can affect uterine function in addition to affecting the ovaries. Here again, the effect depends on the dose; the dose-response relationship has not yet been clearly defined 7 .

| Consensus-based Statement 2.S5 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Irradiation of the uterus can lead to uterine and tubal sterility and to increased pregnancy risks such as preterm birth, miscarriage and lower birth weight of the infant. | |

2.3.4 Radiation damage to the hypothalamic/hypophyseal axis

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.R4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Before undergoing radiotherapy of the head region, patients must be informed about the risk of damaging the hypothalamic/hypophyseal axis and the consequences of this damage. | |

2.4 Gonadal toxicity through immunotherapy or targeted therapies

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.R5 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women receiving therapy with bevacizumab should be informed about the risk of ovarian insufficiency and about methods to preserve fertility. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.R2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients who receive immunotherapy or targeted therapy should be informed about the unclear risk of ovarian insufficiency and about methods to preserve fertility. | |

2.5 Gonadal toxicity from endocrine therapies

| Consensus-based Statement 2.S6 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Data on gonadal toxicity of tamoxifen are limited and inconsistent; there are no data on the possible effects of aromatase inhibitors combined with GnRH agonists. A gonadotoxic effect is unlikely. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 2.S7 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The most important fertility-reducing effect of endocrine therapy used to treat breast cancer is the length of the treatment, as it postpones the time when the patient can have children to a stage in life when patient has reduced ovarian reserve. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.R7 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Ways of protecting fertility such as cryopreservation of fertilized and/or unfertilized oocytes or ovarian tissue should be discussed with women receiving endocrine therapy alone (5 – 10 years) to treat breast cancer. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 2.R8 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| The possibility of postponing or interrupting endocrine therapy may be discussed with the patient if this would allow her to have children early. | |

4 Methods of Fertility Protection for Girls and Women

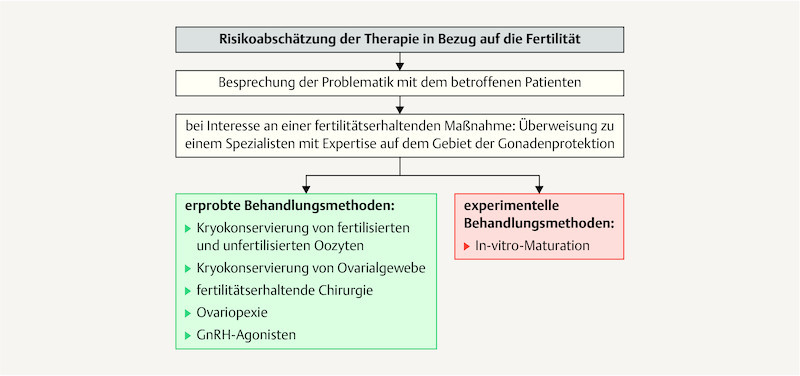

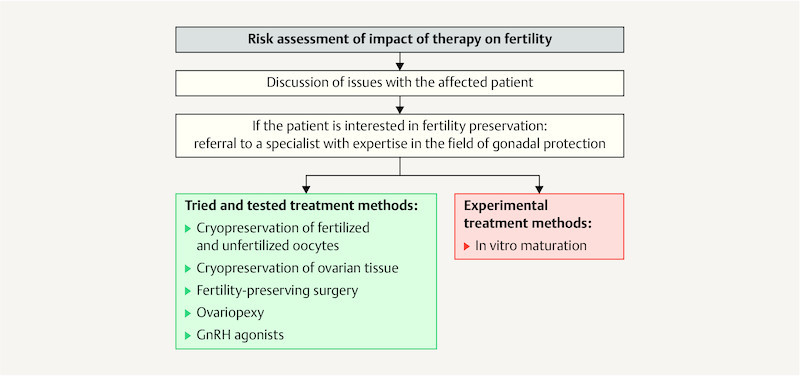

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of potential approaches to protect the fertility of girls and women after the onset of menarche before they start gonadotoxic therapy.

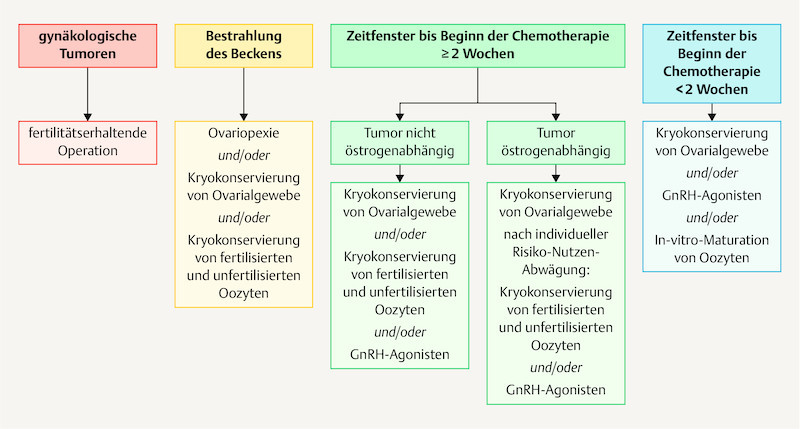

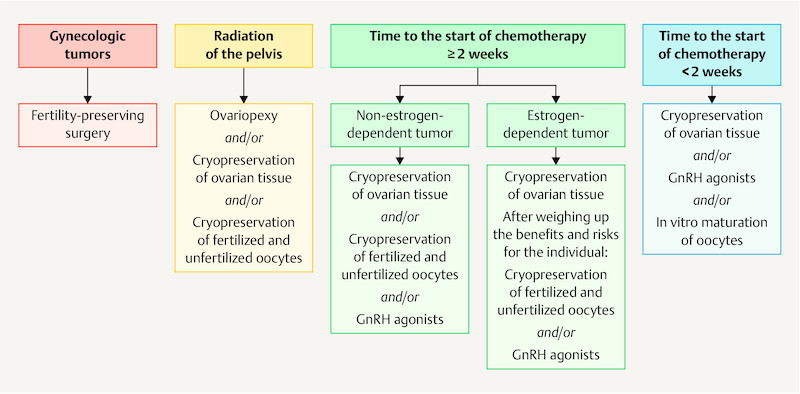

Fig. 2.

Fertility protection for women based on oncologic therapy and the available timeframe (modified from 1 ).

4.1 Organ-preserving surgery

There are a number of S3 guidelines on the treatment of patients with malignant ovarian tumors, cervical cancer und endometrial cancer. To prevent discrepancies between guidelines, the guideline coordinators of the S3 guidelines and the coordinators of the S2k guideline on fertility preservation unanimously agreed to incorporate the relevant Statements, Recommendations and background texts from the S3 guidelines into the S2k guideline. The relevant Recommendations and Statements are available in the long version of the guideline.

4.2 Ovariopexy and gonadal protection for radiotherapy

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S25 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Transposition of the ovaries out of the area which will be irradiated may reduce the risk of radiogenic ovarian insufficiency. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R33 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The possibility of an ovariopexy to preserve ovarian function must be discussed before commencing radiotherapy/radiochemotherapy of the lesser pelvis. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S36 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| If ovariopexy is performed, ovarian tissue may be harvested at the same time for cryopreservation. | |

4.3 GnRH agonists

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S47 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| The data is still contradictory, so administering GnRH agonists as the only method for fertility protection is not sufficient. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S58 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Because of the contradictory study results, it is currently not possible to evaluate the benefit of administering a GnRH agonist. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R34 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Depending on the underlying tumor entity, GnRH agonists may be offered as a fertility protection measure if the patient has been informed in detail. | |

4.4 Cryopreservation of fertilized or unfertilized oocytes

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S19 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Cryopreservation of fertilized and unfertilized oocytes is an established technique in reproductive medicine which can be used before starting gonadotoxic therapy. | |

4.4.1 Controlled ovarian stimulation to harvest oocytes in cancer patients

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S20 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| A protocol with the lowest possible risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome should be used for ovarian stimulation treatment to protect fertility. | |

4.4.2 Cryopreservation of unfertilized oocytes

( Table 6 )

Table 6 Outcomes for unfertilized oocytes after slow freezing or vitrification (modified from 8 and 9 ).

| Slow freezing | Vitrification | |

|---|---|---|

| Survival rate per unfertilized oocyte after cryopreservation/thawing | 45 – 67% | 80 – 90% |

| Fertilization rate per unfertilized oocyte after cryopreservation/thawing | 54 – 68% | 76 – 83% |

| Clinical pregnancy rate/transfers | 11.6% | 44.9% (p = 0.002) |

| Congenital malformation rate | 0.5% | 1.3% |

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S21 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| In contrast to the cryopreservation of fertilized oocytes, the cryopreservation of unfertilized oocytes is not associated with a significantly increased rate of malformations or developmental deficits in children. | |

4.4.3 Cryopreservation of fertilized oocytes

Table 7 Survival rate and development of embryos after slow freezing or vitrification (open/closed) (modified from 10 ).

| Slow freezing | Vitrification (open/closed) | |

|---|---|---|

| * p < 0,001 | ||

| Survival rate per embryo after cryopreservation/thawing | 63.8% | 89.4%*/87.6%* |

| Rate of intact morphology of all blastomeres per embryo after cryopreservation/thawing | 44.3% | 80.1%*/76.1%* |

Table 8 Pregnancy outcomes for blastocysts after slow freezing or vitrification (modified from 11 and 8 ).

| Slow freezing | Vitrification | |

|---|---|---|

| * p = significant, ** ARR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.32–1.45, *** ARR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.34–1.49 | ||

| Rate of transferred blastocysts per cryopreservation/thawing | 71.4% | 84.5%* |

| Rate of clinical pregnancies per transferred blastocyst | 23.8% | 32.7%** |

| Rate of live births per transferred blastocyst | 17.7% | 24.8%*** |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R35 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The cryopreservation of unfertilized oocytes must be additionally offered, even if the patient has a partner. | |

4.5 Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S22 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue is an established method to restore fertility after receiving treatment for cancer. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S23 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue may be carried out at any time of the menstrual cycle and does not lead to any relevant delay in oncologic therapy. | |

4.5.1 Harvesting and transport of ovarian tissue

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R36 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The harvested tissue must be cooled (4 – 8 °C) during its transportation to a center which specializes in cryopreservation. The harvested tissue must be processed promptly, at the very latest 24 hours after harvesting. | |

4.5.2 Cryopreservation of harvested tissue

Slow freezing is currently recommended for the cryopreservation of ovarian tissue because of the higher efficacy of this method in routine clinical practice 12 , 13 , 14 .

4.5.3 Transplantation of tissue

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R37 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Ovarian tissue must be transplanted orthotopically, i.e. on or into the ovary or close to the ovary in the retroperitoneal space. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R38 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The patientʼs fertility (tubal, uterine and extrauterine factors) must be assessed when transplanting ovarian tissue and, if possible, corrections must carried out where necessary. | |

4.5.4 Risk of tumor or disease recurrence after retransplantation

( Table 9 )

Table 9 Risk of ovarian metastasis for various tumor types (modified from Dolmans et al. 14 and Bastings et al. 15 ).

| High risk | Moderate risk | Low risk |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Consensus-based Statement 4.S24 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The risk of ovarian metastasis cannot be excluded for any type of tumor. To date, an increased risk has been found for leukemia, neuroblastoma, Burkittʼs lymphoma and malignant ovarian tumors. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R39 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The patient must be informed before harvesting the tissue about the possible risk of transferring malignant cells by transplanting the harvested ovarian tissue. | |

4.6 Fertility-preserving or fertility-creating/fertility-restoring methods following uterine radiotherapy

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R40 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| If the patient wishes to have children, the dose administered to the uterus must be kept as low as possible using the latest radiation planning and techniques. | |

4.7 Combinations of fertility-protecting methods

| Consensus-based Recommendation 4.R41 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The patient must be offered combinations of different fertility-preserving methods (e.g. cryopreservation of oocytes, cryopreservation of ovarian tissue and/or the administration of GnRH agonists) to improve the efficacy of fertility protection methods. | |

6 Recommendations for Selected Tumor Entities in Women

6.1 Breast cancer

6.1.1 Fertility protection counseling for women with breast cancer

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Every fertile woman with breast cancer who might wish to have children must receive counseling about ovarian toxicity and the available methods to protect fertility before starting any potentially gonadotoxic therapy. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Patients with metastatic breast cancer must receive individualized information on fertility protection which must also take account of the prognosis of a more limited life expectancy. | |

6.1.2 Pregnancy after breast cancer

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S36 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| According to retrospective observational studies, pregnancy after treatment for breast cancer is not associated with a poorer prognosis with regard to the underlying disease. | |

6.1.3 Limited fertility due to chemotherapy for breast cancer

The standard chemotherapy protocols to treat breast cancer in young women are anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapies. The rule of thumb for persistent amenorrhea following anthracycline-taxane-based regimens is estimated to be 10 – 20% for women aged < 30 years, while the rate of persistent amenorrhea for women aged more than 30 years ranges from 13 – 68%, depending on the patientʼs age 16 , 17 .

6.1.4 Limited fertility due to radiotherapy

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S32 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Regional radiotherapy to treat breast cancer is not associated with reduced fertility. | |

6.1.5 Special aspects of fertility protection for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, limited fertility due to endocrine therapy

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R55 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| If the patient has been carefully informed about the potential risks, pausing anti-tumor endocrine therapy (after a minimum of 2 years of therapy) may be considered to allow the patient to have children, after which the patient would resume therapy. | |

6.1.6 Potential fertility protection methods for patients with breast cancer

( Table 10 )

Table 10 Retrospective studies on methods of cryopreservation in women with breast cancer.

| Authors | Study | Number of women | Methods | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawrenz et al., 2012 18 | retrospective, single center | n = 56 | ovarian tissue cryopreservation, GnRHa, hormone stimulation and cryopreservation of oocytes, combinations also possible | Germany |

| Turan et al., 2013 19 | retrospective cohort study single center |

n = 78 | hormone stimulation and cryopreservation of oocytes | USA |

| Sigismondi et al., 2015 20 | retrospective, single center | n = 31 | ovarian tissue cryopreservation, hormone stimulation and cryopreservation of oocytes | Italy |

| Takae et al., 2015 21 | retrospective, single center | n = 27 | combination of ovarian tissue cryopreservation and hormone stimulation with cryopreservation of oocytes | Japan |

| Dahhan et al., 2015 22 | retrospective, single center | n = 16 | hormone stimulation and cryopreservation of oocytes | Netherlands |

| Oktay et al., 2015 23 | retrospective, single center | n = 131 | hormone stimulation with/without letrozole and cryopreservation of oocytes | USA |

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S33 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Irrespective of the patientʼs hormone status, there are no conclusive data about the potential impact of hormone stimulation for oocyte retrieval before starting planned neoadjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer on the patientʼs oncologic prognosis. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R56 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Hormone stimulation for oocyte retrieval can be done in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer receiving concomitant anti-hormone treatment (e.g. aromatase inhibitors or tamoxifen). | |

6.1.7 GnRH agonists (GnRHa) for women with breast cancer

A recent systematic meta-analysis about the use of GnRHa in women with breast cancer 26 evaluated the data from 1962 women, 541 of whom received chemotherapy without GnRHa and 521 of whom were treated with chemotherapy and GnRHa 26 . The rate of spontaneous menstruation recurrence after completing chemotherapy was higher in the group treated with concomitant GnRHa (OR: 2.57; 95% CI: 1.65 – 4.01; p < 0.0001). However, there was no significant difference in pregnancy rates between the two groups. Another recent meta-analysis (n = 1231, 27 ) found a significantly reduced risk of premature ovarian insufficiency (OR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.41 – 0.73, p < 0.001) for patients who received concomitant GnRHa during chemotherapy, together with a slightly but significantly increased pregnancy rate (OR: 1.83; 95% CI: 1.02 – 3.28; p = 0.041).

6.1.8 Reduced ovarian reserve in women with BRCA1 mutation

Comparative studies have pointed out that women with BRCA1 mutation may have reduced ovarian reserve compared to healthy women 24 , 25 .

6.2 Ovarian/borderline tumors

6.2.1 Borderline tumors

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R57 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| After women who have had fertility-preserving surgery to treat an ovarian/borderline tumor and who wish to have children have been informed about the potential risks involved, physicians may consider offering hormone stimulation to them as part of fertility treatment. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R58 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Before undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, women should be offered the possibility of cryopreserving unfertilized and fertilized oocytes. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R59 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue may be considered. | |

6.2.2 Ovarian cancer

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S34 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Fertility treatment is possible in patients with early ovarian cancer (FIGO Ia, G1/G2) who were treated using a fertility-preserving approach and were given detailed information about the risks. | |

6.3 Solid tumors

6.3.1 Sarcomas

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R60 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Every fertile woman with sarcoma who may wish to have a child must be informed about the ovarian toxicity of treatment and the methods of preserving fertility before starting a potentially gonadotoxic therapy. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S35 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| There are no indications that pregnancy after treatment for sarcoma will result in a poorer prognosis. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S36 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Depending on the patientʼs age, chemotherapy to treat osteosarcoma and soft tissue sarcoma will result in primary ovarian insufficiency. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R61 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients with sarcoma should be offered cryopreservation of ovarian tissue to protect fertility. The risk of recurrence caused by transplantation of the tissue cannot be excluded and must be discussed with the patient before harvesting ovarian tissue. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R62 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| After the onset of puberty, patients with sarcoma should be informed about the possibility of cryopreserving oocytes, if the start of oncologic therapy can be postponed by at least 2 weeks. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R63 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| A GnRH agonist can be administered to patients with sarcoma during gonadotoxic therapy. | |

6.3.2 Colorectal cancer

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R64 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Every fertile woman with colorectal cancer who may wish to have a child must be informed about the ovarian toxicity of treatment and methods of preserving fertility before starting a potentially gonadotoxic therapy. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S37 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| According to case reports, pregnancy after rectal cancer is not associated with a poorer oncologic prognosis. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S38 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Chemotherapeutic treatment of colorectal cancer with 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and oxaliplatin is reported to have a low risk of ovarian insufficiency. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R65 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients with colorectal cancer should be offered cryopreservation of ovarian tissue to protect fertility. The risk of disease recurrence caused by transplantation cannot be excluded and must be discussed with the patient before harvesting ovarian tissue. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R66 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| After the onset of puberty, patients with colorectal cancer should be informed about the possibility of cryopreserving oocytes if the start of oncologic therapy can be postponed by at least 2 weeks. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R67 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| A GnRH agonist can be administered to patients with colorectal cancer during gonadotoxic therapy. | |

6.4 Hematologic disease

6.4.1 Lymphomas (Hodgkinʼs and non-Hodgkinʼs lymphoma)

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S39 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| With lymphomas, the risk of primary ovarian insufficiency depends on the chemotherapy protocol used. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R68 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue to protect fertility must be offered to patients with lymphoma who are expected to have a high risk of premature ovarian insufficiency from oncologic therapy. The risk of ovarian metastasis is low for Hodgkinʼs lymphoma and high for non-Hodgkinʼs lymphoma and Burkittʼs lymphoma. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R69 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| After the onset of puberty, patients with lymphoma should be informed about the possibility of cryopreserving oocytes if the start of oncologic therapy can be postponed by at least 2 weeks. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R70 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| A GnRH agonist can be administered to patients with lymphoma during gonadotoxic therapy. This can help prevent thrombocytopenic menorrhagia. | |

6.4.2 Leukemia

6.4.2.1 Acute lymphatic leukemia (ALL)

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S40 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The risk of infertility after treatment for ALL depends on the protocol used for treatment. Women who were treated with a conditioning protocol to prepare them for stem cell transplantation have a high risk of infertility. Patients treated with a conventional protocol have a low risk of infertility. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S41 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Depending on the dose, cranial irradiation during treatment for ALL can lead to treatable impairment of the hypothalamic-hypophyseal axis. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R71 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| Patients with ALL who have a high risk of POI from therapy and who cannot postpone their gonadotoxic therapy can be offered the option of cryopreserving ovarian tissue to protect their fertility. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R72 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The risk of tumor recurrence after autotransplantation of ovarian tissue is considered to be high in patients with ALL, and autotransplantation is therefore not recommended. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R73 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| After the onset of puberty, patients with ALL should be informed about the possibility of cryopreserving oocytes if the start of oncologic therapy can be postponed by at least 2 weeks. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R74 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| A GnRH agonist can be administered to patients with ALL during gonadotoxic therapy. This can help prevent thrombocytopenic menorrhagia. | |

6.4.2.2 Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S42 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The risk of infertility after treatment for AML depends on the protocol used for treatment. Women treated with a conditioning protocol to prepare them for stem cell transplantation have a high risk of infertility. Patients treated with a conventional protocol have a low risk of infertility. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R75 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients with AML who have a high risk of POI from therapy and who cannot postpone their gonadotoxic therapy can be offered the option of cryopreserving ovarian tissue to protect their fertility. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R76 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The risk of tumor recurrence after autotransplantation of ovarian tissue is considered to be high in patients with AML, and autotransplantation is therefore not recommended. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R77 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| After the onset of puberty, patients with AML should be informed about the possibility of cryopreserving oocytes if the start of oncologic therapy can be postponed by at least 2 weeks. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R78 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| A GnRH agonist can be administered to patients with AML during gonadotoxic therapy. This can help prevent thrombocytopenic menorrhagia. | |

6.4.2.3 Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)

| Consensus-based Statement 6.S43 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The risk of ovarian insufficiency following the administration of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) is unclear, with TKI reported to have a teratogenic potential. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R79 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The risk of disease recurrence after autotransplantation of ovarian tissue is considered to be high in patients with CML, and autotransplantation is therefore not recommended. | |

6.4.2.4 Stem cell transplantation

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R80 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Women treated with a conditioning protocol to prepare them for stem cell transplantation have a high risk of infertility. These patients must be informed and receive counseling about methods to protect their fertility. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R81 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus ++ |

| After the onset of puberty and before starting conditioning for stem cell transplantation, patients should be informed about the possibility of cryopreserving oocytes if the start of oncologic therapy can be postponed by at least 2 weeks. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 6.R82 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Patients can be offered the option of cryopreserving ovarian tissue to protect fertility before undergoing stem cell transplantation. | |

8 Malignant Disease in Children and Adolescents

In addition to the established methods to protect fertility before and after treatment for malignant disease mainly targeting post-pubertal boys and girls, experimental methods are also available, particularly for prepubertal children. Listed below are instructions concerning the use of fertility protection methods which need to be taken into account before starting therapy.

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.R92 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The efficacy of administering drugs for fertility protection (e.g. a GnRH agonist) in childhood or early adolescence is still questionable. GnRH agonists must not be administered to prepubertal patients. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.R93 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| Depending on the expected radiation dose administered to the ovary, the possibility of ovariopexy must be discussed during the tumor conference. The recommendation for ovariopexy must be discussed with the patient and her family. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.R94 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| After puberty patients can undergo stimulation treatment to cryopreserve oocytes. This must be done before starting treatment for malignant disease if cancer therapy can be postponed by 2 weeks. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.R95 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| It is currently not clear what the indications for cryopreserving ovarian tissue from prepubertal and peripubertal girls are. The decision for or against cryopreservation requires the type of therapy and the gonadotoxic dose to be weighed up in each individual case. | |

| Consensus-based Recommendation 8.R96 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| After puberty, potential options for fertility preservation include cryopreserving sperm (ejaculation, electrostimulation, testicular biopsy with testicular sperm extraction [TESE]) and cryopreserving testicular tissue as a fertility reserve for assisted reproduction techniques to be used at a later date. The patient and his family must be informed about these options. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 8.S48 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| The cryopreservation of immature testicular tissue extracted by biopsy before the onset of puberty is still in its experimental stages. The subsequent maturation of sperm from spermatogonial stem cells, which would be necessary for this approach, is currently not yet possible in humans. Transplanting cryopreserved tissue always carries the risk of transplanting malignant cells. | |

9 Psychological and Ethical Aspects of Fertility Preservation

| Consensus-based Statement 9.S49 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| All patients of reproductive age with malignant disease and children with malignant disease and their parents should be offered counseling and advice on fertility protection using a biopsychosocial framework. Information about the options for and the limits of fertility protection should be made available to affected patients both orally and in writing (e.g., in the form of publications like “Die Blauen Ratgeber” – a German series of publications issued by the German Cancer Society) through low-threshold publications which enable patients to make their decisions based on informed consent. | |

| Consensus-based Statement 9.S50 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Strength of consensus +++ |

| During open-ended counseling, the different options and perspectives available must be presented and discussed without bias or preference: oncologic therapy without fertility protection, oncologic therapy after fertility protection measures, and pregnancy, childbirth and starting a family must be discussed in ways that take account of different healing processes and courses of disease. | |

Appendix to the Guideline

A standard operating procedure (SOP) on managing the contact with a patient before the patient starts oncologic treatment which will reduce their fertility while the patient may still want to have children is included in the appendix of the long (German) version of the guideline, together with leaflets on preserving fertility which were compiled together with the German Cancer Society (DKG).

Guideline Program. Editors.

Leading Professional Medical Associations

German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e. V. [DGGG]) Head Office of DGGG and Professional Societies Hausvogteiplatz 12, DE-10117 Berlin info@dggg.de http://www.dggg.de/

President of DGGG Prof. Dr. Birgit Seelbach-Göbel Universität Regensburg Klinik für Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde St. Hedwig-Krankenhaus Barmherzige Brüder Steinmetzstraße 1–3, DE-93049 Regensburg

DGGG Guidelines Representative Prof. Dr. med. Matthias W. Beckmann Universitätsklinikum Erlangen, Frauenklinik Universitätsstraße 21–23, DE-91054 Erlangen

Prof. Dr. med. Erich-Franz Solomayer Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes Geburtshilfe und Reproduktionsmedizin Kirrberger Straße, Gebäude 9, DE-66421 Homburg

Guidelines Coordination Dr. med. Paul Gaß, Christina Fuchs, Marion Gebhardt Universitätsklinikum Erlangen Frauenklinik Universitätsstraße 21–23 DE-91054 Erlangen fk-dggg-leitlinien@uk-erlangen.de http://www.dggg.de/leitlinienstellungnahmen

Austrian Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Österreichische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [OEGGG]) Innrain 66A, AT-6020 Innsbruck stephanie.leutgeb@oeggg.at http://www.oeggg.at

President of OEGGG Prof. Dr. med. Petra Kohlberger Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde Wien Währinger Gürtel 18–20, AT-1180 Wien

OEGGG Guidelines Representative Prof. Dr. med. Karl Tamussino Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe Graz Auenbruggerplatz 14 AT-8036 Graz

Prof. Dr. med. Hanns Helmer Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde Wien Währinger Gürtel 18–20, AT-1090 Wien

Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe [SGGG]) Gynécologie Suisse SGGG Altenbergstraße 29, Postfach 6, CH-3000 Bern 8 sekretariat@sggg.ch http://www.sggg.ch/

President of SGGG Dr. med. David Ehm FMH für Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie Nägeligasse 13 CH-3011 Bern

SGGG Guidelines Representative Prof. Dr. med. Daniel Surbek Universitätsklinik für Frauenheilkunde Geburtshilfe und feto-maternale Medizin Inselspital Bern Effingerstraße 102 CH-3010 Bern

Prof. Dr. med. René Hornung Kantonsspital St. Gallen, Frauenklinik Rorschacher Straße 95, CH-9007 St. Gallen

References/Literatur

- 1.von Wolff M, Dian D. Fertilitätsprotektion bei Malignomen und gonadotoxischen Therapien. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:220–226. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schover L R, Rybicki L A, Martin B A. Having children after cancer. A pilot survey of survivorsʼ attitudes and experiences. Cancer. 1999;86:697–709. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<697::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baysal O, Bastings L, Beerendonk C C. Decision-making in female fertility preservation is balancing the expected burden of fertility preservation treatment and the wish to conceive. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1625–1634. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S J, Schover L R, Partridge A H. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2917–2931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambertini M, Del Mastro L, Pescio M C. Cancer and fertility preservation: international recommendations from an expert meeting. BMC Med. 2016;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0545-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace W H, Thomson A B, Saran F. Predicting age of ovarian failure after radiation to a field that includes the ovaries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudour H, Chastagner P, Claude L. Fertility and pregnancy outcome after abdominal irradiation that included or excluded the pelvis in childhood tumor survivors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levi Setti P E, Porcu E, Patrizio P. Human oocyte cryopreservation with slow freezing versus vitrification. Results from the National Italian Registry data, 2007–2011. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:90–9500. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagy Z P, Anderson R E, Feinberg E C. The Human Oocyte Preservation Experience (HOPE) Registry: evaluation of cryopreservation techniques and oocyte source on outcomes. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15:10. doi: 10.1186/s12958-017-0228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasano G, Fontenelle N, Vannin A S. A randomized controlled trial comparing two vitrification methods versus slow-freezing for cryopreservation of human cleavage stage embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0145-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Wang Y A, Ledger W. Clinical outcomes following cryopreservation of blastocysts by vitrification or slow freezing: a population-based cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2794–2801. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine . Ovarian tissue cryopreservation: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meirow D, Roness H, Kristensen S G. Optimizing outcomes from ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation; activation versus preservation. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2453–2456. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolmans M M, Luyckx V, Donnez J. Risk of transferring malignant cells with transplanted frozen-thawed ovarian tissue. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1514–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastings L, Beerendonk C C, Westphal J R. Autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in cancer survivors and the risk of reintroducing malignancy: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:483–506. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sukumvanich P, Case L D, Van Zee K. Incidence and time course of bleeding after long-term amenorrhea after breast cancer treatment: a prospective study. Cancer. 2010;116:3102–3111. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulvat M C, Jeruss J S. Fertility preservation options for young women with breast cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:174–182. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328345525a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrenz B, Henes M, Neunhoeffer E. Fertility conservation in breast cancer patients. Womens Health (Lond) 2011;7:203–212. doi: 10.2217/whe.10.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turan V, Bedoschi G, Moy F. Safety and feasibility of performing two consecutive ovarian stimulation cycles with the use of letrozole-gonadotropin protocol for fertility preservation in breast cancer patients. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1681–16850. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigismondi C, Papaleo E, Vigano P. Fertility preservation in female cancer patients: a single center experience. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34:56–60. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takae S, Sugishita Y, Yoshioka N. The role of menstrual cycle phase and AMH levels in breast cancer patients whose ovarian tissue was cryopreserved for oncofertility treatment. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:305–312. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0392-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahhan T, Mol F, Kenter G G. Fertility preservation: a challenge for IVF-clinics. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;194:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oktay K, Turan V, Bedoschi G. Fertility Preservation Success Subsequent to Concurrent Aromatase Inhibitor Treatment and Ovarian Stimulation in Women With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2424–2429. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oktay K, Kim J Y, Barad D. Association of BRCA1 mutations with occult primary ovarian insufficiency: a possible explanation for the link between infertility and breast/ovarian cancer risks. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:240–244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oktay K, Moy F, Titus S. Age-related decline in DNA repair function explains diminished ovarian reserve, earlier menopause, and possible oocyte vulnerability to chemotherapy in women with BRCA mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1093–1094. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen Y W, Zhang X M, Lv M. Utility of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for prevention of chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage in premenopausal women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2015;8:3349–3359. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S95936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambertini M, Ceppi M, Poggio F. Ovarian suppression using luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists during chemotherapy to preserve ovarian function and fertility of breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized studies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2408–2419. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]