Abstract

Key points:

(a) The lifetime risk of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is approximately 1%; (b) The portal vein is formed by the union of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins posterior to the pancreas; (c) Imaging modalities most frequently used to diagnose PVT include sonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging; (d) Malignancy, hepatic cirrhosis, surgical trauma, and hypercoagulable conditions are the most common risk factors for the development of PVT; (e) PVT eventually leads to the formation of numerous collateral vessels around the thrombosed portal vein; (f) First-line treatment for PVT is therapeutic anticoagulation—it helps prevent the progression of the thrombotic process; (g) Other therapeutic options include surgery and interventional radiographic procedures including mechanical thrombectomy and thrombolysis; (h) Portal biliopathy is a clinicopathologic entity characterized by biliary abnormalities due to portal hypertension secondary to PVT and appears to be more common in cases of extrahepatic PVT.

Republished with permission from:

Quarrie R, Stawicki SP. Portal vein thrombosis: What surgeons need to know. OPUS 12 Scientist 2008;2(3):30-33.

Key Words: Complications, pathophysiology, portal vein thrombosis, risk factors, therapeutic interventions

INTRODUCTION

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is an important clinicopathologic entity that all physicians should be familiar with. PVT is being diagnosed more frequently due to the increasing use of advanced sonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging techniques.[1,2,3,4] According to Ogren et al., the reported lifetime risk of developing PVT in the general population is approximately 1%.[5] However, the incidence may be as high as 30% in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition, PVT is thought to be causative in approximately 8% of portal hypertension cases.[2,5,6,7,8]

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

The portal vein forms behind the neck of the pancreas at the union of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins. It ranges from 5.5 to 8 cm in length, and its diameter is approximately 1 cm. It courses toward the porta hepatis in the free edge of the lesser omentum and receives the cystic, pyloric, accessory pancreatic, and superior pancreaticoduodenal veins, among other tributaries.[9,10]

Most commonly, the portal vein enters the porta hepatis and divides into the right and left main branches. The right main branch of the portal vein divides into anterior and posterior branches that supply the anterior and posterior segments of the right lobe of the liver. The left main branch courses horizontally to the left before turning vertically to form the medial and lateral segmental branches. Several variations of the portal venous anatomy have been described, but their discussion is beyond the scope of this manuscript.[2,8]

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS

Patients with PVT are characterized by a hyperdynamic circulation syndrome similar to that seen in cirrhosis. Liver enzymes and bilirubin are usually normal or only mildly elevated. Quantitative tests such as indocyangreen clearance and galactose elimination capacity demonstrate overall slight functional decrease. Liver biopsy results are typically normal, but hemosiderosis associated with portosystemic shunting has been described. Cavernous transformation of the portal vein – the development of periportal collaterals around the recanalizing or occluded main portal vein – occurs with chronic PVT. Numerous collateral vessels that vary in character from small to markedly enlarged and serpiginous end up functionally “replacing” the portal vein. Doppler sonographic imaging can be used to document blood flow in these periportal collaterals.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Preferred diagnostic examinations in the setting of suspected PVT include Doppler ultrasonography, CT, magnetic resonance angiography, and traditional portography or splenoportography.[10,11,12,13] Nonvisualization of the portal vein is strongly suggestive of occlusion. Portal venous thrombus may be partial or complete. It may have a mixed acute and chronic appearance as well. Of note, a tumor invading the portal vein may have an appearance similar to that of venous thrombosis but is far less common. Tumor invasion of the portal vein is most frequently seen in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma.[14]

In some adult patients with acute PVT associated with abdominal sepsis, the vessel may recanalize following successful treatment of the underlying sepsis/septic source.[1] In other cases, the development of multiple, small, collateral channels can be seen sonographically as a partly echogenic band of small vessels extending to the porta hepatis (cavernous transformation). These collaterals often have a reduced flow velocity of 2–7 cm/s. The portal vein itself may be seen as a band with high-intensity sonographic signal at the porta hepatis.[11,15]

PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS

Risk factors associated with PVT include local (anatomic) risk factors and systemic risk factors [Table 1]. The presence of definitive risk factors can be established in over 85% of cases of PVT, with cancer, hepatic cirrhosis, or recent surgery constituting the most common local (anatomic) risk factors and various thrombophilias constituting the most common systemic risk factors. In a study by Sogaard et al., 87% of patients had one or more risk factors, over 40% of patients have been found to have two risk factors, and over 20% have been noted to have at least three risk factors for PVT.[4]

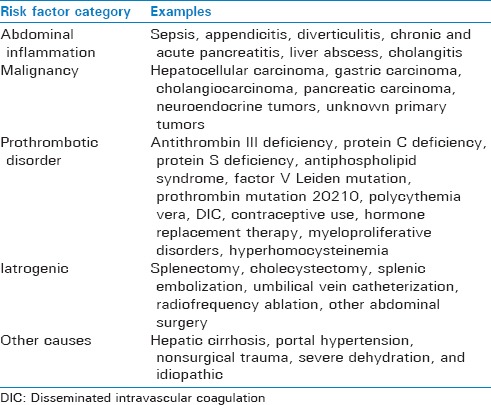

Table 1.

Risk factors for portal vein thrombosis

Specific causes of PVT include the following: (a) idiopathic causes; (b) abdominal sepsis – i.e., appendicitis and diverticulitis; (c) cholangitis; (d) malignancy – hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, among others; (e) trauma – surgical and nonsurgical; (f) iatrogenic – i.e., umbilical vein catheterization, interventional embolization procedures; (g) pancreatitis; (h) perinatal omphalitis; (i) myeloproliferative disorders; (j) clotting disorders (hypercoagulable syndromes); (k) estrogen therapy; (l) severe dehydration; (m) cirrhosis, especially in the younger patient; and (n) portal hypertension.[1,2,4,5,7,8,16,17,18,19]

PVT has also been described as a rare but potentially fatal complication of splenectomy.[17,19] In this setting, PVT should be suspected in a patient with unexpected fever and/or atypical abdominal pain following the surgical removal of the spleen. Patients with a myeloproliferative disorder or hemolytic anemia may be at higher risk of this complication. These groups may benefit from early detection of PVT by Doppler ultrasonography after splenectomy.

ACUTE VERSUS CHRONIC PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS

Clinical presentation of acute PVT may include abdominal pain, splenomegaly, fever, and new-onset ascites. Sogaard et al. reported a higher frequency of abdominal pain and fever in patients with acute PVT than in those with chronic PVT. The incidence of ascites in the acute presentation of PVT varies from study to study, depending on the use of advanced ultrasonography and CT [Figure 1]. For example, Sogaard et al. reported ascites to be present in over 40% of patients with acute PVT using routine sonographic assessments.[4]

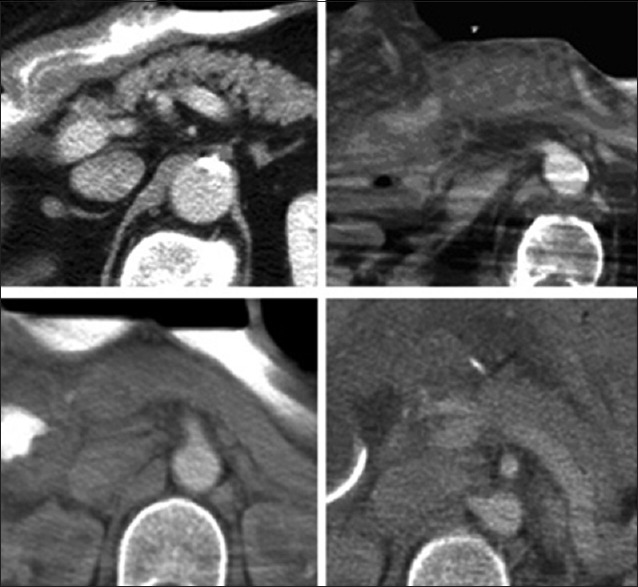

Figure 1.

Examples of portal vein thrombosis as seen on computed tomographic imaging. Top left, widely patent main portal vein in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Top right, same patient following hepatic trisegmentectomy procedure – note the poor visualization of the thrombosed portal vein. Bottom left, portal vein thrombosis following intraoperative portal venous injury. Bottom right, following operative thrombectomy, portal venous flow has been successfully re-established

Chronic PVT may present with abdominal pain; portal-systemic encephalopathy; or gastrointestinal hemorrhage associated with esophageal varices, splenomegaly, and/or ascites. In most patients, PVT progresses slowly and silently. In fact, PVT frequently goes unnoticed until gastrointestinal hemorrhage or other sequelae develop. Variceal bleeding may occur in both acute and chronic PVT. However, it is seen most commonly with chronic PVT.[20,21]

Symptoms of the underlying cause of the PVT, such as acute pancreatitis, intra-abdominal sepsis, or ascending cholangitis, may overshadow the nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms of PVT. The radiologist may be the first physician to suggest the diagnosis on the basis of imaging findings as the thrombosis is often discovered during routine radiographic surveillance for another pathologic condition. Exceptions to this scenario include patients with hypercoagulable syndromes and acute portal and mesenteric venous thrombosis who present with moderate or severe abdominal complaints after acute or subacute development of the thrombosis.

Portal biliopathy is a clinicopathologic entity characterized by bile duct and gallbladder wall abnormalities in association with portal hypertension, particularly with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction.[22] Cavernous transformation of the portal vein, choledochal varices, and ischemic injury of the bile ducts have been postulated as causes. Portal cavernous transformation gives rise to many dilated pericholedochal and periportal collaterals that functionally bypass the portal venous obstruction. Extrinsic compression of the common duct by dilated venous collaterals together with pericholedochal fibrosis from the inflammatory process associated with portal thrombosis may lead to biliary stricturing and dilatation of the proximal biliary tree. This condition sometimes causes the formation of secondary biliary stones and cholangitis. Most patients remain asymptomatic, but some present with elevated alkaline phosphatase level, abdominal pain, fever, and cholangitis.

TREATMENT OF PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS

Most patients with PVT are treated with immediate anticoagulation therapy.[1,4] This is most often performed through continuous intravenous heparin infusion, but some authors report using low-molecular-weight heparin. Chronic treatment options include warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin. Initial treatment of PVT should consist of anticoagulation with heparin if the patient is not experiencing any active bleeding.

This recommendation is supported by Condat et al., who demonstrated a favorable risk–benefit ratio for anticoagulation therapy in patients with acute PVT.[6] Anticoagulation should be maintained for at least 6 months and may need to be continued beyond that period depending on the cause of thrombosis. The addition of an antiplatelet agent in patients with a myeloproliferative disease does not appear to increase the risk of subsequent bleeding.

Other more invasive treatment modalities used in the setting of PVT include transjugular catheterization of occluded veins, local thrombolytic infusion directly into the area of thrombosis or into the superior mesenteric artery, the creation of a transjugular portosystemic shunt, stent implantation, and mechanical thrombectomy.[23] The experience with interventional techniques in the setting of PVT is still limited, and the benefit of these procedures remains to be fully defined.[18,24,25,26,27] There are, however, an increasing number of case reports that document the successful use of interventional radiology for both mechanical and pharmacologic thrombolysis in the setting of PVT.[24,25,26,27] For example, Rossi et al. describe the use of percutaneous transhepatic catheterization with mechanical and pharmacologic thrombolysis.[26] They recommend that mechanical thrombectomy be performed first followed by local pharmacologic thrombolysis to achieve enhanced dissolution of the thrombus. Ozkan et al. also support the use of interventional radiologic techniques for mechanical and pharmacological thrombolysis, indicating that continued refinements in these techniques are contributing to their emergence as preferred methods of invasive therapy for PVT.[24] Surgical interventions such as thrombectomy or shunting are certainly more invasive and are associated with their own set of complications.[16,27]

PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: OUTCOMES

Spontaneous resolution of PVT can be observed in some cases, with the frequency of partial or complete portal venous recanalization being higher among patients treated with anticoagulation therapy. Partial or complete resolution may occur in patients with both acute and chronic PVT.[1,6]

For patients who develop variceal disease, aggressive variceal bleeding prevention should be instituted, with the most effective pharmacologic strategy consisting of nonselective beta-blocking agents. Variceal disease may show most dramatic regression in patients who are treated with a combination of active endoscopic interventions and pharmacologic therapy.[20,21]

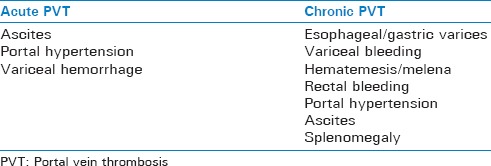

Clinical outcomes of PVT are generally good. This is especially true of PVT that is not associated with cirrhosis or malignancy. Mortality tends to be related more to the underlying disease process and less so to the direct consequences of PVT or portal hypertension. According to Sogaard et al., mortality is highest in patients with cancer or hepatic cirrhosis (26%) compared with 8% in patients without these conditions.[4] Morbidity, on the other hand, can be significant. Ascites and/or gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to portal hypertension are seen all-to-frequently in the setting of chronic PVT [Table 2].

Table 2.

Complications associated with portal vein thrombosis

CONCLUSIONS

PVT is an important pathologic entity that all clinicians should be familiar with. There are many associated risk factors for the development of PVT. In cases where PVT is suspected, Doppler ultrasonography and/or CT imaging of the abdomen are the most readily available and effective methods of diagnosing this condition. Acute PVT most commonly presents with abdominal pain, fever, and ascites while chronic PVT can present with gastric bleeding. Anticoagulation is the principal method of treating this condition barring any contraindications. Interventional radiologic techniques, including mechanical thrombectomy, thrombolysis, and stenting, are becoming more popular. Open surgical approaches are often difficult and plagued by significant associated morbidity. Long-term prognosis of PVT is good in patients without underlying malignancy or cirrhosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Justifications for re-publishing this scholarly content include: (a) The phasing out of the original publication – the OPUS 12 Scientist and (b) Wider dissemination of the research outcome (s) and the associated scientific knowledge.

REFERENCES

- 1.Condat B, Pessione F, Helene Denninger M, Hillaire S, Valla D. Recent portal or mesenteric venous thrombosis: Increased recognition and frequent recanalization on anticoagulant therapy. Hepatology. 2000;32:466–70. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan AN, MacDonald S, Sheen AJ, Sherlock D, Al-Khattab Y. Portal Vein Thrombosis. [Last accessed on 2008 Jun 10]. Available from: http://www.emedicine.com/radio/topic571.htm .

- 3.Ricci P, Cantisani V, Biancari F, Drud FM, Coniglio M, Di Filippo A, et al. Contrast-enhanced color Doppler US in malignant portal vein thrombosis. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:470–3. doi: 10.1080/028418500127345703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sogaard KK, Astrup LB, Vilstrup H, Gronbaek H. Portal vein thrombosis; risk factors, clinical presentation and treatment. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogren M, Bergqvist D, Björck M, Acosta S, Eriksson H, Sternby NH, et al. Portal vein thrombosis: Prevalence, patient characteristics and lifetime risk: A population study based on 23,796 consecutive autopsies. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2115–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i13.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condat B, Pessione F, Hillaire S, Denninger MH, Guillin MC, Poliquin M, et al. Current outcome of portal vein thrombosis in adults: Risk and benefit of anticoagulant therapy. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:490–7. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kocher G, Himmelmann A. Portal vein thrombosis (PVT): A study of 20 non-cirrhotic cases. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:372–6. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.11035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponziani FR, Zocco MA, Campanale C, Rinninella E, Tortora A, Di Maurizio L, et al. Portal vein thrombosis: insight into physiopathology, diagnosis, and treatment. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2010;14:16–143. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglass BE, Baggenstoss AH, Hollinshead WH. The anatomy of the portal vein and its tributaries. Surgery, gynecology and obstetrics. Surgery, gynecology and obstetrics. 1950;91:562–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanlin E. Portal vein thrombosis: A primer for emergency medicine physicians. [Last accessed on 2018 May 07]. Available from: http://www.emdocs.net/portal-vein-thrombosis-primer-emergency-medicine-physicians/

- 11.Davis M, Chong WK. Doppler ultrasound of the liver, portal hypertension, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Ultrasound Clinics. 2014;9:587–604. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tublin ME, Dodd GD, 3rd, Baron RL. Benign and malignant portal vein thrombosis: differentiation by CT characteristics. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1997;168:719–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.3.9057522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zirinsky K, Markisz JA, Rubenstein WA, Cahill PT, Knowles RJ, Auh YH, et al. MR imaging of portal venous thrombosis: correlation with CT and sonography. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1988;150:283–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson SM, Wells ML, Andrews JC, Ehman EC, Menias CO, Hallemeier CL, et al. Venous invasion by hepatic tumors: Imaging appearance and implications for management. Abdominal Radiology. 2017:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth CG, Mitchell DG. Vascular Liver Disease. New York: Springer; 2011. Radiological Diagnosis; pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein M, Link DP. Symptomatic spleno-mesenteric-portal venous thrombosis: Recanalization and reconstruction with endovascular stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:363–71. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(99)70044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van't Riet M, Burger JW, van Muiswinkel JM, Kazemier G, Schipperus MR, Bonjer HJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of portal vein thrombosis following splenectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1229–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Stefano DR, de Baere T, Denys A, Hakime A, Gorin G, Gillet M, et al. Preoperative percutaneous portal vein embolization: Evaluation of adverse events in 188 patients. Radiology. 2005;234:625–30. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342031996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita F, Lyass S, Otsuka K, Giordano L. Portal vein thrombosis following splenectomy: Identification of risk factors. The American surgeon. 2003;69:951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brett BT, Hayes PC, Jalan R. Primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:349–58. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villanueva C, Miñana J, Ortiz J, Gallego A, Soriano G, Torras X, et al. Endoscopic ligation compared with combined treatment with nadolol and isosorbide mononitrate to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:647–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandra R, Kapoor D, Tharakan A, Chaudhary A, Sarin SK. Portal biliopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1086–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivitz SM, Geller SC, Hahn C, Waltman AC. Treatment of acute mesenteric venous thrombosis with transjugular intramesenteric urokinase infusion. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:219–23. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozkan U, Oğuzkurt L, Tercan F, Tokmak N. Percutaneous transhepatic thrombolysis in the treatment of acute portal venous thrombosis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2006;12:105–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poplausky MR, Kaufman JA, Geller SC, Waltman AC. Mesenteric venous thrombosis treated with urokinase via the superior mesenteric artery. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1633–5. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi C, Zambruni A, Ansaloni F, Casadei A, Morelli C, Bernardi M, et al. Combined mechanical and pharmacologic thrombolysis for portal vein thrombosis in liver-graft recipients and in candidates for liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:938–40. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000137104.38602.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryu R, Lin TC, Kumpe D, Krysl J, Durham JD, Goff JS, et al. Percutaneous mesenteric venous thrombectomy and thrombolysis: Successful treatment followed by liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:222–5. doi: 10.1002/lt.500040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]