ABSTRACT

Device infection remains a significant challenge as clinical indications for cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) therapy continue to expand beyond the prevention and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. Patients receiving CIED therapy are now older and have significant comorbidities, placing them at higher risk of complications, including infection. CIED infection warrants complete device removal, as retention is associated with an unacceptably high risk of relapse and increased mortality. However, accurate diagnosis of CIED infections remains a significant challenge that is based on a combination of findings on physical examination, microbiological and laboratory testing, and advanced imaging, such as transesophageal echocardiography or positron emission tomography. Isolating a causative pathogen and performing susceptibility testing are crucial for appropriate choice, route, and duration of antimicrobial therapy. In this review, we present an evidence-based approach to diagnosis of CIED infection.

KEYWORDS: pacemaker, ICD, CIED infection, diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Advances in cardiovascular sciences and device manufacturing have led to an expansion of indications for the use of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs), which now include permanent pacemakers (PPMs), implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), and cardiac resynchronizing therapy (CRT) devices. Over the past 6 decades, the use of these devices has decreased hospitalizations and lowered morbidity and mortality for many patients. However, with a rapid and steady increase in CIED implantation rates, a higher than expected increase in CIED infection rates has been observed (1). CIED infections carry significant risks of morbidity and mortality and impose a large cost burden to the health care system (2). Device infection warrants complete system removal, including generator and intracardiac leads. Lead extraction procedures are complex and carry the risk of complications, including laceration of major vessels, damage to the tricuspid valve, myocardial tears, and major bleeding. Several studies have shown that retention or delayed removal of infected cardiac devices is associated with high mortality and that chronic antimicrobial suppression in CIED infection is suboptimal, with the risk of relapse (2). Therefore, accurate diagnosis of CIED infection is paramount, as it mandates device removal. Misdiagnosis may result in unnecessary risk and cost to the patient.

The diagnosis of CIED infection is established with a combination of clinical findings, microbiologic testing, and diagnostic imaging. Here, we will review clinical manifestations of CIED infection and an approach to optimal use of laboratory testing and imaging studies for prompt and accurate diagnosis of CIED infection, as summarized below.

Diagnostic workup for suspected CIED infection

Preoperative

Obtain complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin levels.

- Obtain 2 sets of blood samples prior to initiating empirical antibiotic therapy.

- Routine blood samples should be sent for culture to recover aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including Candida species.

- Blood samples comprising 1 Bactec plus 1 aerobic/F bottle and 1 Bactec lytic/10 anaerobic/F bottle should be collected and incubated on an automated Bactec FX instrument for 5 days.

- For culture-negative CIED infection, especially in the setting of central venous catheters and immunocompromised hosts, special fungal/mycobacterial blood cultures may be helpful to isolate the causative pathogen.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) should be performed in patients with positive blood cultures or the presence of systemic symptoms but negative blood cultures due to prior antibiotic therapy.

- TEE is preferred over transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) due to its ability to detect smaller valvular vegetations, perivalvular extension of infection, and lead vegetations.

Intraoperative

- Swab samples from the device.

- Send to microbiology laboratory for Gram staining, bacterial cultures, and susceptibility testing.

- If suspected, consider fungal and mycobacterial cultures, including fungal and acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smears.

Generator pocket tissue samples for culture and susceptibility testing.

- Device sonication.

- Place extracted device into a sterile jar/container with 50 to 100 ml of sterile saline and seal before submitting to microbiology laboratory.

PATHOGENESIS OF CIED INFECTION

There are several microbial virulence factors that contribute to the development and persistence of CIED infection, including adherence factors, biofilm formation, and microbial persistence (3). CIED infection begins with the attachment of the microbe to the device surface. Certain microorganisms, such as staphylococci, contain multiple surface adhesins that allow binding to host extracellular matrix components, such as fibronectin, fibrinogen, and collagen, that coat the outer surface of a device (3). These surface adhesins are termed microbial surface components reacting with adherence matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) (4). The Staphylococcus aureus genome contains several MSCRAMM genes, with clumping factor A (ClfA) and fibronectin-binding proteins A and B (FnBPA and FnBPB) being known to cause cardiovascular infections (3).

The ability of staphylococci to attach to a device and form a multilayered biofilm may be the most important virulence factor these microorganisms possess, allowing them to remain on the surface of a device indefinitely (3, 5). Once formed, biofilms trap bacteria, rendering their existence in a dormant state and limiting the penetration of antibiotics to reach microbes embedded in the deeper layers (3). Bacteria in the deeper layers of biofilm become metabolically less active and slow to replicate, thus limiting the bactericidal activity of cell wall-active agents, such as beta-lactams or glycopeptides (3). This microbial persistence is the primary reason for high rates of relapse and increased mortality in patients who do not have their device removed (4, 5). In addition, the presence of biofilm makes it difficult to isolate and culture the causative pathogens, as they are embedded in the biofilm, and pocket swabs and tissue cultures are frequently negative, especially in patients who have received antibiotic therapy prior to device extraction (6).

Small-colony variants (SCVs) are an interesting and unique virulence factor in the pathogenesis of CIED infections due to staphylococci. SCVs of Staphylococcus aureus represent a subpopulation of naturally occurring phenotypes with distinctive characteristics and pathogenic traits (3). These SCVs have a low growth rate, decreased antibiotic susceptibility to aminoglycosides, and decreased phagocytosis, and they present a significant challenge to antimicrobial susceptibility testing (3).

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

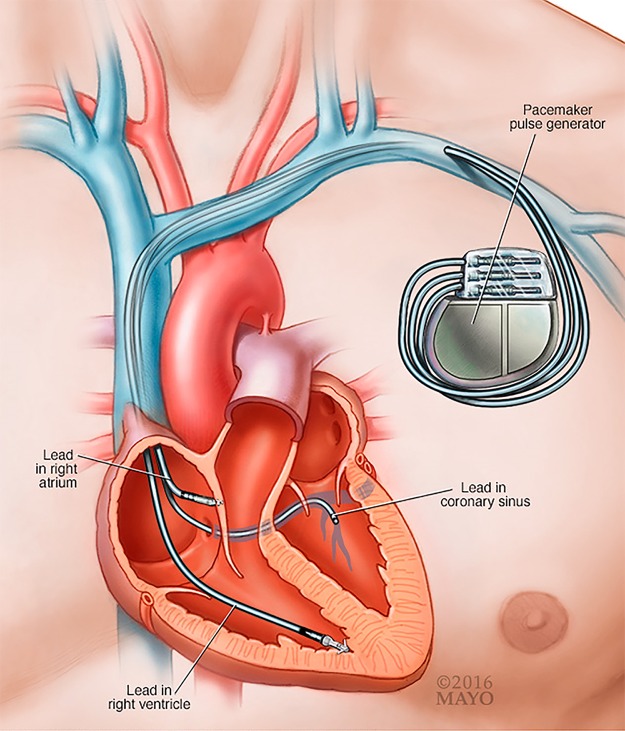

A CIED is composed of a generator that contains the battery and electronics and is connected via 1 to 3 transvenous wires to the heart to provide functions of cardiac pacing, defibrillation, and/or resynchronization (Fig. 1). The device generator is most commonly placed in the pectoral region. In some patients, the wires may be placed under the sternum or epicardium. Once infection involves any segment of the device, the entire system is considered infected.

FIG 1.

Transvenous CIED lead and pocket generator. (Courtesy of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Reproduced with permission.)

Device infection can be acquired due to contamination of the generator or leads at the time of CIED system implantation or replacement, erosion of the device through intact skin, or hematogenous seeding of leads or pocket due to bloodstream infection from a secondary source (3, 4). The risk of hematogenous seeding of a device from a distant source of bacteremia depends on the causative organism and timing of onset of bacteremia from the date of device implantation (7).

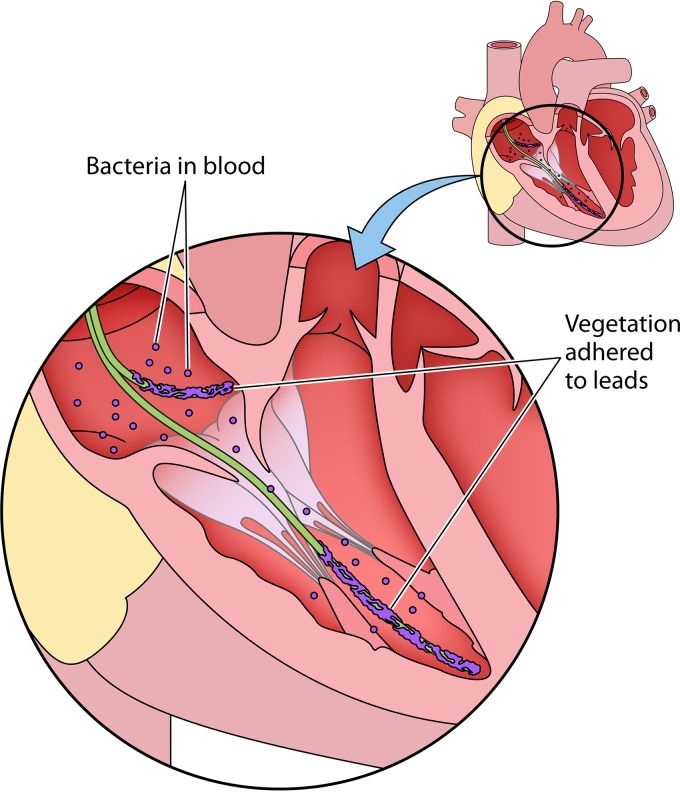

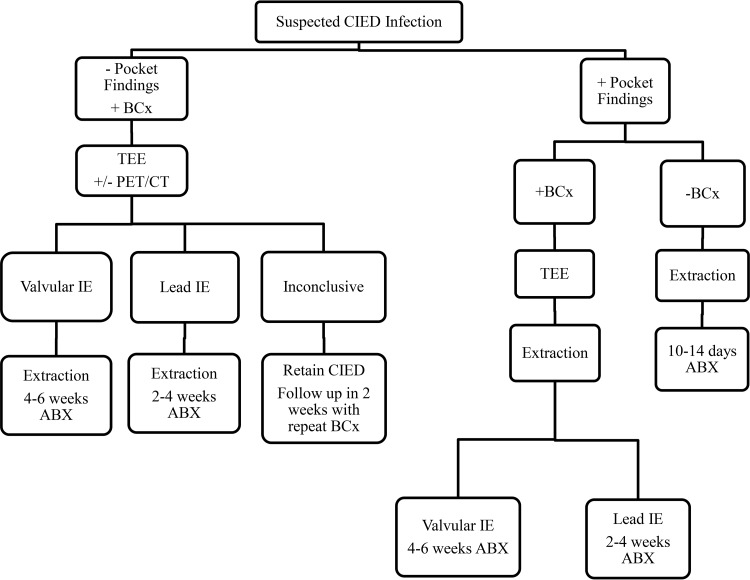

Patients with a CIED infection typically present with the following four scenarios (6, 8, 9): (i) local inflammatory changes at the generator pocket site, such as erythema, swelling, pain, discomfort, drainage, or erosion of the generator and/or leads through the skin; (ii) fever and no local changes at the generator pocket site; (iii) bacteremia and no local changes at the generator pocket site; or (iv) lead thrombus or vegetation on echocardiography (Fig. 2). A systematic approach to CIED infection diagnosis and treatment for these scenarios is shown in Fig. 3. Proposed Mayo CIED infection classification criteria are presented below. Based on clinical, microbiological, and pocket findings, patients are classified as having definite, probable, or possible CIED infection.

FIG 2.

CIED lead vegetation.

FIG 3.

Systematic approach to CIED infection diagnosis and treatment. −, negative; +, positive; BCx, blood culture; IE, infective endocarditis; ABX, antibiotics.

Proposed Mayo CIED infection classification criteria

Pocket findings

Physical exam: device erosion through skin, purulence emanating from pocket, fluctuance, or sinus tract.

Intraoperative findings: purulence within the generator pocket site.

Cultures: positive cultures (significant microbial growth, i.e., tissue and swab sample growth when colonies grow on ł2 quadrants of the culture plate and device sonication sample growth when ł20 colonies are isolated from 10 ml of sonicate fluid [10]) from explanted CIED.

Clinical findings

Major

Two or more positive blood cultures for organisms typical of CIED infection, such as S. aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), or enterococci, with no alternative source.

TEE findings consistent with vegetation on the device lead and/or heart valve.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging consistent with device infection.

Minor

Prolonged bacteremia (>72 h) with microorganisms other than listed in major criteria.

TEE findings not meeting major criteria.

Recent pocket manipulation (<3 months prior to presentation).

Fever (38°C or higher).

Embolic phenomena (typically septic pulmonary emboli from lead vegetations or right-sided endocarditis).

Pocket erythema or tenderness.

CIED infection classification criteria

Definite CIED infection: combination of any 2 major clinical findings or 1 or more pocket findings.

Probable CIED infection: 1 major clinical finding and 1 or more minor clinical findings.

Possible CIED infection: suspected CIED infection case that does not meet “Definite” or “Probable” criteria.

When patients present with local inflammatory changes at the generator pocket site or with CIED erosion, the diagnosis is usually straightforward. The majority of these patients do not have fever or other systemic symptoms, and often pain or discomfort at the generator site is the sole reason for seeking medical attention (6). However, occasionally it can be difficult to distinguish early-onset generator pocket infection from superficial cellulitis at the surgical site, contact dermatitis due to the adhesive dressings, or allergy to pacemaker components (8).

Patients living with CIEDs who present with fever but no inflammatory signs at the generator pocket site and without an obvious alternative focus of infection require additional workup. These patients should have at least 2 sets of blood samples drawn prior to starting any empirical antibiotic therapy (6). If blood cultures are negative but the patient has received antibiotic therapy prior to blood samples being drawn, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) may be useful in demonstrating device lead infection or valvular endocarditis (6). If blood cultures are positive, then the identification of the microorganism plays a major role in determining the next step—whether to obtain TEE or look for an alternative source of infection (8). Occasionally, patients with CIEDs may undergo TEE for a non-infection-related indication and be found to have a mass or echodensity attached to a device lead or the tricuspid valve. These mostly represent thrombi or fibrin strands or degenerative valve changes. However, it is important to recognize that echocardiography cannot reliably distinguish between a sterile thrombus and an infected-lead vegetation (6). Accurate distinction between the two pathologies is critical, as the CIED system should not be unnecessarily removed in patients with sterile lead thrombi, whereas complete system removal is warranted for infected-lead vegetations.

MICROBIOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS

Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) and S. aureus are the major pathogens involved in 60 to 80% of reported CIED infections, followed by Gram-negative bacillus, fungus, polymicrobial, and other Gram-positive coccus infections and culture-negative cases (4, 9). All patients with suspected CIED infection should receive a detailed physician examination and laboratory evaluation (see “Diagnostic workup for suspected CIED infection” above). Two sets of blood cultures should be obtained prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy. However, blood cultures are frequently negative in patients with local pocket infection. In one investigation by Sohail et al. (7), in 189 cases of CIED infections from 1991 to 2003 at the Mayo Clinic, blood sample cultures were positive only in 40% of all cases. In a similar study by Chua et al. (5), at the Cleveland Clinic, approximately 33% of cases with CIED infection had positive blood sample cultures. These findings demonstrate that the majority of patients with CIED infection are not bacteremic at the time of diagnosis. This highlights the importance of culturing samples from the pocket tissue and the device, including the lead tip and sonicate fluid, to identify the causative pathogen.

At the time of CIED removal, appropriate collection of specimens includes pocket swab samples, pocket tissue samples, device swab samples, including the lead tip, and device sonicate fluid samples to accurately identify the infecting microorganism, especially when blood cultures are negative. Pocket tissue sample cultures have been shown to be more effective than pocket swab cultures in identifying a microorganism in CIED infections (11). However, cultures of device lead samples are more accurate than either pocket tissue or pocket swab sample cultures (12, 13).

Sonication has been used in microbiological diagnosis in orthopedic infections, particularly prosthetic joint infections. The sonication process involves disruption of biofilm on device surfaces using ultrasound waves, resulting in the release of bacteria embedded on the device surface into the sonicate fluid. A cardiac device is removed from a patient and placed into a sterile jar, and then Ringer's solution is added and the mixture vortexed for 30 s, followed by sonication (frequency 40 ± 2 kHz) in an ultrasound bath for 5 min and then by vortexing for an additional 30 s. Fifty milliliters of the sonicate fluid is then placed in a tube and centrifuged for 5 min, and samples placed onto aerobic and anaerobic sheep blood agar plates. The supernatant is aspirated, leaving 0.5 ml remaining in the tube, 0.1 ml of which is plated onto an aerobic and another 0.1 ml onto an anaerobic sheep blood agar plate, and the plates incubated at 35°C to 37°C in 5% to 7% CO2 aerobically for 4 days and anaerobically for 14 days (10, 14). This process provides a sensitive method to detect bacteria involved in foreign body infections (15). Multiple studies have demonstrated the utility of a sonication process to improve culture yield in cases of CIED infection, with some variation in the sonication techniques (10, 15, 16). For example, Mason et al. (16) used 100 ml of sterile saline, sonicated the device at a frequency of 42 ± 6 kHz, and sent the fluid to the laboratory for culture. Rohacek et al. (15) did not centrifuge, but rather, repeated 30 s of vortexing after sonication. Oliva et al. (17) suggested sonication for 5 min at a frequency of >20 kHz, with repeat vortexing followed by centrifugation at 3,200 rpm for 20 min and then culture plating.

Samples obtained by sonication have been shown to be more sensitive than pocket swab samples or blood samples in identifying the causative microorganism in CIED infections (15). In one investigation, Nagpal et al. (10) showed that vortexing and sonication of CIEDs with semiquantitative culture of the sonicate fluid resulted in a significant increase in the sensitivity of culture results compared with the sensitivity of pocket swab or tissue sample cultures (bacterial growth was observed in 54% of sonicate fluid cultures versus 20% of pocket swab cultures, 9% of device swab cultures, and 9% of tissue sample cultures). Moreover, sonication can also detect asymptomatic colonization of CIED surfaces in clinically uninfected cases (18). However, the significance of this asymptomatic colonization is unclear. In two different investigations, patients with asymptomatic colonization were not at higher risk of future pocket infection (16).

RADIOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS

When patients present with erosion of device components or purulent drainage from the pocket site, the diagnosis of CIED infection is quite simple. However, occasionally it may be difficult to distinguish between early-onset superficial surgical site infection and a true generator pocket infection. Also, diagnosis of device lead infection can be challenging when patients only present with bloodstream infection and no local findings at the generator pocket. Advanced diagnostic imaging techniques, such as TEE, radionucleotide leukocyte scan (99mTc-hexamethypropylene amine oxime-labeled autologous white blood cell [99mTc-HMPAO WBC] scan), and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography (18F-FDG PET–CT) can be helpful in these difficult cases.

TEE is significantly more sensitive than transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) in diagnosing CIED-related infective endocarditis (>95% versus <50%) (4). However, TEE cannot always distinguish a sterile mass or a thrombus on the CIED lead from an infected vegetation. Failure to visualize a mass on the device lead with TEE in a patient with bacteremia and no alternative source, however, does not exclude device infection with certainty (4). Therefore, findings on TEE must be interpreted in the clinical context.

The role of 99mTc-HMPAO WBC scintigraphy with single-photon-emission computed tomography–computed tomography (SPECT-CT) has been studied as adjunctive diagnostic testing in cardiovascular infections (19). This modality detects and localizes metabolically active cells involved in inflammation and infection and has been used in the diagnosis of native and prosthetic valve infective endocarditis where echocardiography findings were inconclusive (19, 20). In the study by Erba et al. (19), 99mTc-HMPAO WBC scintigraphy was 94% sensitive for both detection and localization of CIED infection and associated complications, with a 95% negative predictive value to reliably exclude device-associated infection during a febrile episode and sepsis.

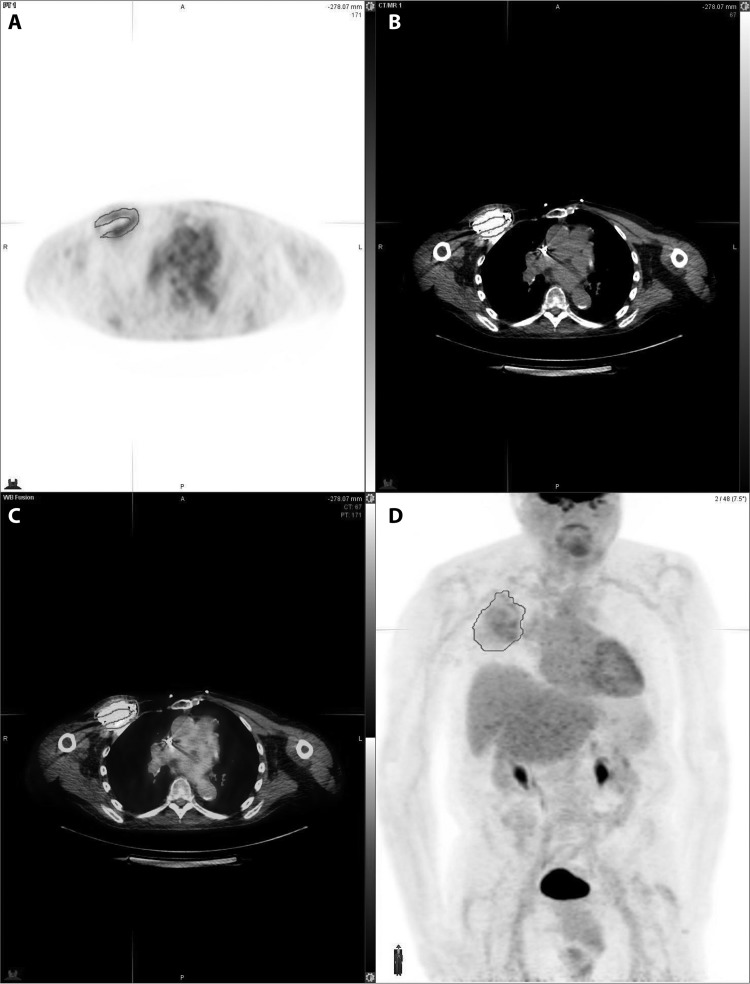

The diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET–CT scanning in CIED infections has been evaluated in multiple studies (21–24). 18F-FDG PET–CT was found helpful in differentiating between true CIED infection and residual postoperative inflammation that may be present within 2 months of implantation (21). In the investigation by Sarrazin et al., patients with suspected CIED infection but a negative 18F-FDG PET–CT scan were managed conservatively and remained infection free at the 12-month follow-up (21). A recent meta-analysis by Mahmood et al. (25) evaluated the role of PET-CT for diagnosis of CIED infection in 14 studies involving 492 patients. Overall, the pooled sensitivity of PET-CT for diagnosis of CIED infection was 83% and the pooled specificity was 89%. PET-CT demonstrated higher sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 97% for diagnosis of pocket infections. However, the diagnostic accuracy for lead infections or CIED-related endocarditis was lower, with pooled sensitivity of 76% and specificity of 83%. Figure 4 presents axial PET, axial CT, axial fused PET-CT, and fused images from a 53-year-old male showing increased FDG activity at the pocket of the CIED, most consistent with infection. Guidelines from the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) do not recommend routine use of FDG PET-CT scanning outside research studies but do mention that it may be useful in selected cases when there is uncertainty about generator pocket infection (9).

FIG 4.

Axial PET (A), axial CT (B), axial fused PET-CT (C), and fused (D) images from a 53-year-old male show increased FDG activity at the pocket of the CIED, most consistent with infection.

BIOMARKER-BASED DIAGNOSIS

The use of biomarkers has been found beneficial in a variety of disease processes. Their use in the diagnosis of CIED infections was examined in one investigation by Lennerz et al. (26) A total of 25 patients with confirmed pocket infection were enrolled. Investigators obtained preoperative levels of selected biomarkers, including white blood cell count, C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, lipopolysaccharide binding protein, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), polymorphonuclear elastase, presepsin, various interleukins, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Compared to the results for 50 control patients, there were statistically significantly elevated procalcitonin and hs-CRP levels in the infected group. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that procalcitonin and hs-CRP can aid in the diagnosis of CIED infection (26).

CONCLUSION

Diagnosis of CIED infection relies on expertise from cardiology and infectious disease specialists, combining findings from physical examination, laboratory and microbiological techniques, and advanced imaging modalities in order to accurately identify infected cases and causative pathogens. Complete CIED system removal is warranted to cure device infections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenspon AJ, Patel JD, Lau E, Ochoa JA, Frisch DR, Ho RT, Pavri BB, Kurtz SM. 2011. 16-year trends in the infection burden for pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in the United States 1993 to 2008. J Am Coll Cardiol 58:1001–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan EM, DeSimone DC, Sohail MR, Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Steckelberg JM, Virk A. 2017. Outcomes in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic device infection managed with chronic antibiotic suppression. Clin Infect Dis 64:1516–1521. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagpal A, Baddour LM, Sohail MR. 2012. Microbiology and pathogenesis of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 5:433–441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patti JM, Allen BL, McGavin MJ, Hook M. 1994. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu Rev Microbiol 48:585–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chua JD, Wilkoff BL, Lee I, Juratli N, Longworth DL, Gordon SM. 2000. Diagnosis and management of infections involving implantable electrophysiologic cardiac devices. Ann Intern Med 133:604–608. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baddour LM, Epstein AE, Erickson CC, Knight BP, Levison ME, Lockhart PB, Masoudi FA, Okum EJ, Wilson WR, Beerman LB, Bolger AF, Estes NA III, Gewitz M, Newburger JW, Schron EB, Taubert KA. 2010. Update on cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections and their management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121:458–477. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH, Friedman PA, Hayes DL, Wilson WR, Steckelberg JM, Stoner S, Baddour LM. 2007. Management and outcome of permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infections. J Am Coll Cardiol 49:1851–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeSimone DC, Sohail MR. 2016. Management of bacteremia in patients living with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm 13:2247–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandoe JA, Barlow G, Chambers JB, Gammage M, Guleri A, Howard P, Olson E, Perry JD, Prendergast BD, Spry MJ, Steeds RP, Tayebjee MH, Watkin R. 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of implantable cardiac electronic device infection. Report of a joint Working Party project on behalf of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC, host organization), British Heart Rhythm Society (BHRS), British Cardiovascular Society (BCS), British Heart Valve Society (BHVS) and British Society for Echocardiography (BSE). J Antimicrob Chemother 70:325–359. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagpal A, Patel R, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Baddour LM, Lynch DT, Lahr BD, Maleszewski JJ, Friedman PA, Hayes DL, Sohail MR. 2015. Usefulness of sonication of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices to enhance microbial detection. Am J Cardiol 115:912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dy Chua J, Abdul-Karim A, Mawhorter S, Procop GW, Tchou P, Niebauer M, Saliba W, Schweikert R, Wilkoff BL. 2005. The role of swab and tissue culture in the diagnosis of implantable cardiac device infection. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 28:1276–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golzio PG, Vinci M, Anselmino M, Comoglio C, Rinaldi M, Trevi GP, Bongiorni MG. 2009. Accuracy of swabs, tissue specimens, and lead samples in diagnosis of cardiac rhythm management device infections. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 32(Suppl 1):S76–S80. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bongiorni MG, Tascini C, Tagliaferri E, Di Cori A, Soldati E, Leonildi A, Zucchelli G, Ciullo I, Menichetti F. 2012. Microbiology of cardiac implantable electronic device infections. Europace 14:1334–1339. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inacio RC, Klautau GB, Murca MA, da Silva CB, Nigro S, Rivetti LA, Pereira WL, Salles MJ. 2015. Microbial diagnosis of infection and colonization of cardiac implantable electronic devices by use of sonication. Int J Infect Dis 38:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rohacek M, Erne P, Kobza R, Pfyffer GE, Frei R, Weisser M. 2015. Infection of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices: detection with sonication, swab cultures, and blood cultures. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 38:247–253. doi: 10.1111/pace.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason PK, Dimarco JP, Ferguson JD, Mahapatra S, Mangrum JM, Bilchick KC, Moorman JR, Lake DE, Bergin JD. 2011. Sonication of explanted cardiac rhythm management devices for the diagnosis of pocket infections and asymptomatic bacterial colonization. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 34:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliva A, Nguyen BL, Mascellino MT, D'Abramo A, Iannetta M, Ciccaglioni A, Vullo V, Mastroianni CM. 2013. Sonication of explanted cardiac implants improves microbial detection in cardiac device infections. J Clin Microbiol 51:496–502. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02230-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohacek M, Weisser M, Kobza R, Schoenenberger AW, Pfyffer GE, Frei R, Erne P, Trampuz A. 2010. Bacterial colonization and infection of electrophysiological cardiac devices detected with sonication and swab culture. Circulation 121:1691–1697. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.906461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erba PA, Sollini M, Conti U, Bandera F, Tascini C, De Tommasi SM, Zucchelli G, Doria R, Menichetti F, Bongiorni MG, Lazzeri E, Mariani G. 2013. Radiolabeled WBC scintigraphy in the diagnostic workup of patients with suspected device-related infections. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 6:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erba PA, Conti U, Lazzeri E, Sollini M, Doria R, De Tommasi SM, Bandera F, Tascini C, Menichetti F, Dierckx RA, Signore A, Mariani G. 2012. Added value of 99mTc-HMPAO-labeled leukocyte SPECT/CT in the characterization and management of patients with infectious endocarditis. J Nucl Med 53:1235–1243. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarrazin JF, Philippon F, Tessier M, Guimond J, Molin F, Champagne J, Nault I, Blier L, Nadeau M, Charbonneau L, Trottier M, O'Hara G. 2012. Usefulness of fluorine-18 positron emission tomography/computed tomography for identification of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. J Am Coll Cardiol 59:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed FZ, James J, Cunnington C, Motwani M, Fullwood C, Hooper J, Burns P, Qamruddin A, Al-Bahrani G, Armstrong I, Tout D, Clarke B, Sandoe JA, Arumugam P, Mamas MA, Zaidi AM. 2015. Early diagnosis of cardiac implantable electronic device generator pocket infection using 18F-FDG-PET/CT. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 16:521–530. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juneau D, Golfam M, Hazra S, Zuckier LS, Garas S, Redpath C, Bernick J, Leung E, Chih S, Wells G, Beanlands RS, Chow BJ. 2017. Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography imaging in the diagnosis of cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 10:e005772. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granados U, Fuster D, Pericas JM, Llopis JL, Ninot S, Quintana E, Almela M, Pare C, Tolosana JM, Falces C, Moreno A, Pons F, Lomena F, Miro JM. 2016. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT in infective endocarditis and implantable cardiac electronic device infection: a cross-sectional study. J Nucl Med 57:1726–1732. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.173690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmood M, Kendi AT, Farid S, Ajmal S, Johnson GB, Baddour LM, Chareonthaitawee P, Friedman PA, Sohail MR. 14 September 2017. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol doi: 10.1007/s12350-017-1063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lennerz C, Vrazic H, Haller B, Braun S, Petzold T, Ott I, Lennerz A, Michel J, Blazek P, Deisenhofer I, Whittaker P, Kolb C. 2017. Biomarker-based diagnosis of pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator pocket infections: a prospective, multicentre, case-control evaluation. PLoS One 12:e0172384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]