Abstract

Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs (AAnPs) are common in marine environments and are associated with photoheterotrophic activity. To date, AAnPs that possess the potential for carbon fixation have not been identified in the surface ocean. Using the Tara Oceans metagenomic dataset, we have identified draft genomes of nine bacteria that possess the genomic potential for anoxygenic phototrophy, carbon fixation via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle, and the oxidation of sulfite and thiosulfate. Forming a monophyletic clade within the Alphaproteobacteria and lacking cultured representatives, the organisms compose minor constituents of local microbial communities (0.1–1.0%), but are globally distributed, present in multiple samples from the North Pacific, Mediterranean Sea, the East Africa Coastal Province, and the Atlantic. This discovery may require re-examination of the microbial communities in the oceans to understand and constrain the role this group of organisms may play in the global carbon cycle.

Introduction

A central tenant of in our current understanding of marine microbiology is that aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (AAnPs) are heterotrophic and lack the capacity for carbon fixation [1]. AAnPs utilize type-II photochemical reaction centers (RCIIs) and the photopigment bacteriochlorophyll to harness light energy in order to translocate protons across the cytoplasmic membrane [2, 3]. The presence and abundance of AAnPs in marine environments has been studied extensively, revealing a phylogenetically diverse [4, 5] and globally distributed group of microorganisms [6]. AAnPs with the capacity of carbon fixation have not been recognized, unlike anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophs, such as Rhodobacter sphaeroides, which will only perform photosynthesis under suboxic or anoxic conditions [7, 8]. Utilizing the microbial metagenomes generated during the Tara Oceans expedition [9, 10] and the subsequent microbial metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) generated through various studies [11, 12, 13], we have identified the genomes of a globally-distributed, novel alphabacterial clade that encodes the genes necessary for aerobic anoxygenic phototrophy and carbon fixation through the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle. While further research will be required to ascertain the extent to which anoxygenic phototrophy and carbon fixation interact within these organisms, it is possible this may represent a new mode of photosynthesis in the global ocean.

Materials and methods

A collection of non-redundant MAGs generated from several studies using the Tara Oceans metagenomic dataset [11–13] and from the Red Sea [14] were screened for the predicted presence of genes assigned as the M and L subunits of type-II photochemical reaction center (PufML) and the large and small units of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase (RbcLS, RuBisCO). A detailed methodology can be found in the Supplemental Information.

Results and discussions

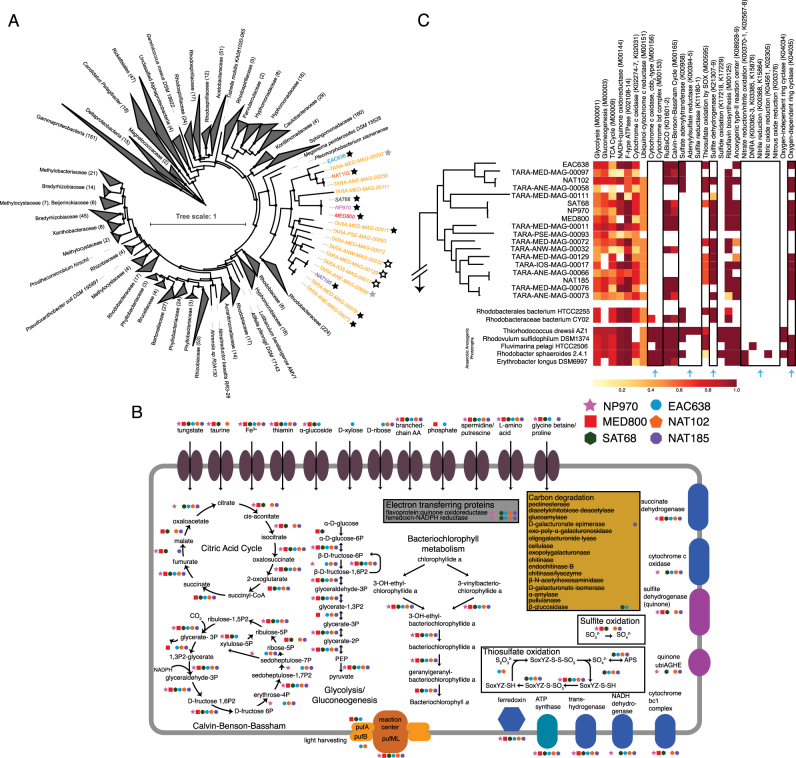

A collection of 3655 marine microbial MAGs were screened for the presence of the genes encoding PufML, resulting in the identification of 102 genomes. Within this group of anoxygenic phototrophs, nine genomes were identified (six from Tully et al. [11] and three from Delmont et al. [12]) that also encoded the genes for RbcLS. The nine genomes of interest are of varying degrees of quality with estimated completion values of 38–95% (mean: 76%) and a limited amount of strain non-specific contamination (Table 1). Along with nine other genomes lacking the genes for PufML and/or RbcLS, they form a distinct sister clade to the Rhodobacteraceae (Fig. 1a), absent of cultured or genomic representatives in NCBI GenBank [15]. As is common for MAGs, none of the genomes possessed a full-length 16S rRNA gene sequence. A partial, 90 bp 16S rRNA gene fragment in one MAG was linked to a clade of 16S rRNA genes assigned to an uncultured group of organisms associated with the Rhodobacteraceae. To represent the novel nature of this clade, we propose the creation of a family level group that encompasses all 18 genomes with the tentative name ‘Candidatus Luxescamonaceae’ (L. fem. lux, light; L. fem. esca, food; Gr. fem. monas, a unit, monad; N.L. fem. n. Luxescamonaceae, the light and food monad).

Table 1.

Summary of genome statistics for the putative members of the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’

| Genome ID | PufM presence | RbcL presence | No. of contigs | Total length (bp) | Max. contig length (bp) | N50 | Mean length (bp) | GC (%) | No. of predicted CDSa | Est. completeness (%)b | Est. contamination (Est. strain heterogeneity) (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAT185c,d | + | + | 90 | 2,235,338 | 199,971 | 38,700 | 24,761 | 38.0 | 2,198 | 94.77 | 0.39 (66.67) |

| NAT102c,d | + | + | 105 | 1,995,055 | 67,548 | 22,200 | 18,995 | 37.7 | 1,936 | 86.20 | 0.67 (0.00) |

| NP970c,d | + | + | 119 | 2,435,294 | 84,644 | 32,121 | 20,380 | 36.1 | 2,359 | 82.71 | 2.00 (33.33) |

| SAT68c,d | + | + | 192 | 2,295,506 | 62,884 | 13,375 | 11,880 | 37.1 | 2,351 | 80.00 | 5.53 (71.88) |

| MED800c,d | + | + | 176 | 2,162,263 | 55,714 | 13,593 | 12,191 | 37.0 | 2,219 | 69.75 | 2.80 (100.00) |

| EAC638c,d | + | + | 197 | 2,499,174 | 80,634 | 14,967 | 12,620 | 30.9 | 2,599 | 66.59 | 1.20 (100.00) |

| TARA-MED-MAG-00011d,e | + | + | 100 | 1,971,082 | 70,540 | 31,135 | 19,710 | 37.7 | 1,949 | 88.20 | 0.40 (0.00) |

| TARA-MED-MAG-00076e | + | + | 86 | 1,475,546 | 86,697 | 22,424 | 17,157 | 37.4 | 1,475 | 75.60 | 0.53 (50.00) |

| TARA-ANE-MAG-00073d,e | + | + | 142 | 811,509 | 16,501 | 6438 | 5714 | 38.6 | 858 | 38.24 | 0.00 (0.00) |

| TARA-MED-MAG-00097e | − | + | 168 | 982,411 | 26,063 | 6725 | 5874 | 36.1 | 1,058 | 63.97 | 0.93 (100.00) |

| TARA-ANE-MAG-00058d,e | − | − | 136 | 907,139 | 38.673 | 7370 | 6670 | 37.6 | 966 | 59.48 | 1.16 (80.00) |

| TARA-MED-MAG-00111e | − | − | 133 | 848,198 | 26,144 | 6958 | 6377 | 34.9 | 960 | 59.27 | 1.81 (33.33) |

| TARA-PSE-MAG-00093d,e | − | − | 70 | 1,073,290 | 53,951 | 19,516 | 15,332 | 27.7 | 1,144 | 72.10 | 0.13 (100.00) |

| TARA-MED-MAG-00072e | − | − | 332 | 1,996,491 | 57,250 | 6935 | 6013 | 36.8 | 2,103 | 78.65 | 0.93 (66.67) |

| TARA-ANW-MAG-00032d,e | + | − | 211 | 1,576,546 | 29,415 | 9704 | 7471 | 39.2 | 1,674 | 73.03 | 1.20 (33.33) |

| TARA-MED-MAG-00129d,e | + | − | 259 | 1,489,684 | 20,564 | 6389 | 5751 | 39.2 | 1,579 | 50.59 | 0.00 (0.00) |

| TARA-IOS-MAG-00017e | + | − | 210 | 2,258,247 | 64,859 | 15147 | 10,753 | 38.7 | 2,269 | 91.57 | 1.10 (12.50) |

| TARA-ANE-MAG-00066e | − | + | 276 | 1,221,441 | 16,829 | 4451 | 4425 | 38.3 | 1,371 | 58.85 | 1.40 (57.14) |

N50—length of contig for which all contigs longer in length contain half of the total genome

CDS—coding DNA sequence

a Determined using Prodigal

b Determine using CheckM with the Alphaproteobacteria markers (388 markers in 250 sets)

c MAGs determined in Tully et al. [11]

d MAGs manually refined in this study

e MAGs determined in Delmont et al. [12]

Fig. 1.

a Phylogenomic tree of 31 concatenated marker genes for the Alphaproteobacteria. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of genomes collapsed within a branch. Black stars denote genomes within the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ that possess PufM and RbsL; gray stars denote genomes that possess RbsL only; white stars denote genomes that possess PufM only. Bootstrap values >0.75 are shown. Circle size representing the bootstrap value is scaled from 0.75–1.0. b Cellular schematic comparing the six AAnP genomes derived from Tully et al. [11]. c Comparison of predicted functions for the entire ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ clade, selected neighbors, and previously described anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Dendrogram represents the phylogenetic relationship between members of the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’. Black boxes and blue arrows denote specific comparison discussed in the manuscript. Predicted functions are represented on a scale from 0 to 1 denoting the fraction of completeness a pathway or function has within a genome. KEGG module or ontology IDs used to determine function completeness are noted

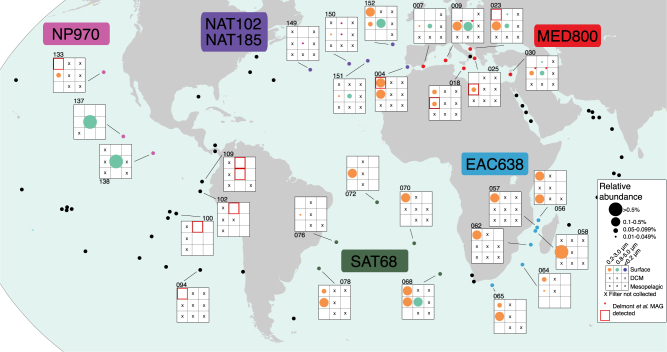

The nine AAnP genomes from this novel clade were detected in 51 samples from 29 stations in the Tara Oceans metagenomic dataset at >0.01% relative abundance (max. ~1.0% relative abundance; Fig. 2; Supplemental Information 1). Just under half of those samples (n = 21) had approximately >0.1% relative abundance (max. ~1.0%), with the highest abundance in a sample from the North Pacific (TARA137, 1.04%). Tara Oceans metagenomic samples were classified in to three partially overlapping size classes (<0.2, 0.2–3.0, 0.8–5.0 μm) and collected from three depths (surface, deep chlorophyll maximum [DCM], and mesopelagic). Predominantly, the AAnP genomes of interest occur in metagenomic samples from the 0.2–3.0 μm size fraction at the shallower sampling depths (surface and DCM), suggesting that these organisms occur as a component of the ‘free-living’ fraction of the microbial community in the photic zone. In many instances, the genomes can be detected from the same depth in medium and large size fractions, for which the most parsimonious explanation would be that cells are regularly in in the 0.8–3.0 μm size range.

Fig. 2.

Global map illustrating the Tara Oceans sampling sites. Sites at which the AAnP members of the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ were detected at >0.01% relative abundance are depicted. For each site, filter size fractions that were not collected are represented by an ‘X’ and each column represents one of the three Tara Oceans filter size fractions. Red asterisks denote filter fractions in which the relative abundance of genomes from Delmont et al. [12] contributed at least 0.01% (max. 0.04%) of the total relative abundance (this study). Squares highlighted in red denote filter samples in which ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ genomes from Delmont et al. [12] had a reported relative fraction of the metagenome of 0.01–0.03% [12]

Phylogenetic assessments of the RbcL and PufM sequences was performed to contextualize the AAnP genomes relative to the established diversity. The ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ AAnP RuBisCO sequences clustered with the Type-IC/D RuBisCOs, suggesting that the AAnP sequences are bona fide RuBisCOs capable of carbon fixation (Supplemental Figure 1). Specifically, the AAnP sequences exclusively clustered with environmental RuBisCOs identified in the Global Ocean Survey (GOS) dataset. PufM sequences from the AAnP genomes cluster in two distinct clades that consist only of environmental GOS sequences (Supplemental Figure 2). Interestingly, PufM sequences in the clade encompassing NP970, SAT68, and MED800 do not match the canonical pufM primers and may explain why this group has not been previously identified [5, 16–19].

A comparative analysis of the six genomes generated in Tully et al. [11] reveals the genomic capacity for complete carbon fixation via the CBB cycle, the biosynthesis of bacteriochlorophyll, and the oxidation of inorganic sulfur compounds, either thiosulfate via the SOX system and/or sulfite via sulfite dehydrogenase (Fig. 1b). An expanded comparison of the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ clade and the genomes of anaerobic anoxygenic phototrophs reveals a distinct lack of microaerobic cytochromes, specifically cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase [20] and cytochrome bd-type [21], and the inability to utilize alternative electron acceptors, such as nitrate, nitrite, and sulfate (Fig. 1c). Additionally, all of the AAnP from the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ also possess oxygen-dependent ring cyclase (acsF) necessary for bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in oxic environments. Collectively, it would suggest that the genomes in the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ with RCII and RuBisCO are true AAnP, capable of lithoautotrophic growth through the oxidation of various sulfur compounds [22].

Conclusion

The potential for the metabolic link between RCII and CBB in a previously unidentified clade of Alphaproteobacteria may be a new avenue of photosynthesis in the ocean. It should be noted that despite identification of the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ in reconstructed MAGs from independent assembly and binning methodologies, MAGs remain an imperfect tool due to the nature of incomplete genomic content and the influence of contaminating DNA sequences. One avenue to test how the RCII apparatus and the CBB cycle are connected under oxic conditions would be the identification of simultaneous expression of both metabolic pathways. However, due to low abundance of these organisms in natural assemblages and known confounding issues in expression, such as the staggered expression of photosynthesis genes in Cyanobacteria [23], it will likely be difficult to observe this under in situ conditions. Attempts utilizing publicly-available ribosomal rRNA de novo removed metatranscriptomes from Tara Oceans (Accession No.: ERS490659, ERS494518, ERS1092158, ERS490542) generated read coverage values in a range well below accepted quantifiable ranges. With this consideration, it seems likely that targeted identification of expression (e.g., qPCR) and/or the isolation/enrichment of members of this clade will be required to explore the potential metabolism of these organisms.

Data availability

For the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ genomes generated from Tully et al. [11], the original genomes can be accessed at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank with the Whole Genome Shotgun project deposited under the accessions: PAHT01000000, PACC01000000, PBQX01000000, PAKN01000000, PAGE01000000, NZPY01000000. For the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ genomes generated from Delmont et al. [12], the original genomes can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.4902923. Updated genomes, as the result of the applied refinement step, originating from Delmont et al. [12] can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.5615011.v1. Update genomes, as the result of the applied refinement step, originating from Tully et al. [11] can be accessed with the GenBank accessions: PAHT02000000, PACC02000000, PBQX02000000, PAKN02000000, PAGE02000000, NZPY02000000.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank Drs. Eric Webb and William Nelson for providing invaluable comments and critiques in the early stages of this research. We are indebted to the Tara Oceans consortium for their commitment to open-access data that allows data aficionados to indulge in the data and attempt to add to the body of science contained within. And we thank the Center for Dark Energy Biosphere Investigations (C-DEBI) for providing funding to BJT and JFH (OCE-0939654). This is C-DEBI contribution number 418.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-018-0091-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Moran MA. The global ocean microbiome. Science. 2015;350:aac8455–aac8455. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Béjá O, Spudich EN, Spudich JL, Leclerc M, DeLong EF. Proteorhodopsin phototrophy in the ocean. Nature. 2001;411:786–9. doi: 10.1038/35081051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harashima K, Kawazoe K, Yoshida I, Kamata H. Light-stimultated aerobic growth of erythrobacter species Och-114. Plant Cell Physiol. 1987;28:365–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koblížek M. Ecology of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015;39:854–70. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Béjá O, Suzuki MT, Heidelberg JF, Nelson WC, Preston CM, Hamada T, et al. Unsuspected diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Nature. 2002;415:630–3. doi: 10.1038/415630a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwalbach MS, Fuhrman JA. Wide‐ranging abundances of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the world ocean revealed by epifluorescence microscopy and quantitative PCR. Limnol Oceanogr. 2005;50:620–8. doi: 10.4319/lo.2005.50.2.0620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu YS, Kaplan S. Effects of light, oxygen, and substrates on steady-state levels of mRNA coding for ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and light-harvesting and reaction center polypeptides in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:925–32. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.925-932.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biel AJ, Marrs BL. Transcriptional regulation of several genes for bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata in response to oxygen. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:686–94. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.686-694.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pesant S, Not F, Picheral M, Kandels-Lewis S, Le Bescot N, Gorsky G, et al. Open science resources for the discovery and analysis of Tara Oceans data. Sci Data. 2015;2:150023–16. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2015.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunagawa S, Coelho LP, Chaffron S, Kultima JR, Labadie K, Salazar G, et al. Ocean plankton. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science. 2015;348:1261359–1261359. doi: 10.1126/science.1261359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tully BJ, Graham ED, Heidelberg JF. The reconstruction of 2,631 draft metagenome-assembled genomes from the global oceans. Sci Data. 2018;5:170203. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delmont TO, Quince C, Shaiber A, Esen ÖC, Lee STM, Lücker S, et al. Nitrogen-fixing populations of planctomycetes and proteobacteria are abundant in the surface ocean. bioRxiv. 2017;129791:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tully BJ, Sachdeva R, Graham ED, Heidelberg JF. 290 metagenome-assembled genomes from the Mediterranean Sea: a resource for marine microbiology. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3558–15. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haroon MF, Thompson LR, Parks DH, Hugenholtz P, Stingl U. A catalogue of 136 microbial draft genomes from Red Sea metagenomes. Sci Data. 2016;3:160050–6. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D34–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Achenbach LA, Carey J, Madigan MT. Photosynthetic and phylogenetic primers for detection of anoxygenic phototrophs in natural environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2922–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.7.2922-2926.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagashima K, Hiraishi A, Shimada K, Matsuura K. Horizontal transfer of genes coding for the photosynthetic reaction centers of purple bacteria. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:131–6. doi: 10.1007/PL00006212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tank M, Blümel M, Imhoff JF. Communities of purple sulfur bacteria in a Baltic Sea coastal lagoon analyzed by pufLM gene libraries and the impact of temperature and NaCl concentration in experimental enrichment cultures. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2011;78:428–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yutin N, Suzuki MT, Béjà O. Novel primers reveal wider diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8958–62. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8958-8962.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Thöny-Meyer L, Appleby CA, Hennecke H. A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1532–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1532-1538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’mello R, Hill S, Poole RK. The cytochrome bd quinol oxidase in Escherichia coli has an extremely high oxygen affinity and two oxygen-binding haems: implications for regulation of activity in …. Microbiology. 1996;142:755–63. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swan BK, Martinez-Garcia M, Preston CM, Sczyrba A, Woyke T, Lamy D, et al. Potential for chemolithoautotrophy among ubiquitous bacteria lineages in the Dark Ocean. Science. 2011;333:1296–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.1203690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson ST, Aylward FO, Ribalet F, Barone B, Casey JR, Connell PE, et al. Coordinated regulation of growth, activity and transcription in natural populations of the unicellular nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Crocosphaera. Nat Microbiol. 2017;17118:1–9. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ genomes generated from Tully et al. [11], the original genomes can be accessed at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank with the Whole Genome Shotgun project deposited under the accessions: PAHT01000000, PACC01000000, PBQX01000000, PAKN01000000, PAGE01000000, NZPY01000000. For the ‘Ca. Luxescamonaceae’ genomes generated from Delmont et al. [12], the original genomes can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.4902923. Updated genomes, as the result of the applied refinement step, originating from Delmont et al. [12] can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.5615011.v1. Update genomes, as the result of the applied refinement step, originating from Tully et al. [11] can be accessed with the GenBank accessions: PAHT02000000, PACC02000000, PBQX02000000, PAKN02000000, PAGE02000000, NZPY02000000.