Abstract

Background

In Western settings, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) due to Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) is relatively rare. Previous studies from Asia, however, indicate a higher prevalence of GNB in CAP, but data, particularly from Southeast Asia, are limited.

Methods

This is a prospective observational study of 1451 patients ≥15 y of age with CAP from two hospitals in Cambodia between 2007 and 2010. The proportion of GNB was estimated. Risk factors and clinical characteristics of CAP due to GNB were assessed using logistic regression models.

Results

The prevalence of GNB was 8.6% in all CAP patients and 15.8% among those with a valid respiratory sample. GNB infection was independently associated with diabetes, higher leucocyte count and CAP severity. Mortality was higher in patients with CAP due to GNB.

Conclusions

We found a high proportion of GNB in a population hospitalized for CAP in Cambodia. Given the complex antimicrobial sensitivity patterns of certain GNBs and the rapid emergence of multidrug-resistant GNB, microbiological laboratory capacity should be strengthened and prospective clinical trials comparing empiric treatment algorithms according to the severity of CAP are needed.

Keywords: Cambodia, Community acquired, Epidemiology, Gram-negative bacilli, Pneumonia, Pseudomonas

Introduction

Previous studies of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) have reported varying incidences of Gram-negative bacilli (GNB). Numerous studies from Europe and North America have shown that GNB are not a common aetiology1,2 and a significant prevalence mainly affects high-risk populations.1–3 Although limited, previous studies from Asia indicate that GNB is a more common cause of CAP, particularly in Southeast Asia.4,5

Initial antibiotic treatment for CAP is empiric. First-line treatment recommendations mainly target Streptococcus pneumoniae, the major causative pathogen in most parts of the world.6 While GNB have repeatedly been associated with severe disease presentation and adverse prognosis,1,2,7 the choice of appropriate antibiotic treatment in CAP is further complicated by the emergence of multidrug resistance among GNB, particularly in Asia, since excessive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for common infections can be harmful.8 It is therefore important to define the frequency of GNB in CAP in Southeast Asia and to identify risk factors to provide support for clinicians in determining which patients merit deviation from the advocated first-line antibiotic therapy.

In this prospective study we estimate the prevalence of GNB in patients admitted to hospital for CAP, identify their risk factors and clinical predictors and assess CAP-related mortality in Cambodia, a low-income country in Southeast Asia.

Methods

Study population

From April 2007 to July 2010, a prospective surveillance study of acute lower respiratory tract infections was conducted in Cambodia, in the Takeo and Kampong Cham provincial hospitals. The study hospitals were located in Takeo province (estimated population 0.9 million) and Kampong Cham province (estimated population 1.7 million), both located approximately 150 km from the capital. The participating hospitals could provide supplementary oxygen, but mechanical or non-invasive ventilation and computed tomography (CT) scan were unavailable. Details of patient recruitment and the methodology have been described elsewhere.9 Patients were eligible if admitted to hospital with symptoms of acute lower respiratory tract infection, defined as onset ≤14 d, fever ≥38°C or a history of febrile episodes within 3 days and cough and at least one respiratory sign (dyspnoea, chest pain or crackles on lung auscultation) without any hospitalization in the previous 3 weeks and without any known tuberculosis (TB), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or active cancer. The decision to hospitalize was left to the clinicians’ judgement. The study was approved by the Cambodian National Ethics Committee for Health Research (024-NECHR). Written informed consent was obtained from patients ≥18 y of age or the parents/guardians of children. In the present study we included individuals ≥15 y of age (the age cut-off for admission to adult wards in Cambodia) with radiological and clinical signs compatible with CAP.

Data collection

Demographic, clinical and treatment data were recorded. On admission the following investigations were performed on all patients: chest X-ray, collection of blood and non-induced sputum for microbiological cultures and consecutive samples for direct sputum examination for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and nasopharyngeal swab for polymerase chain reaction tests for 18 viral respiratory pathogens, including human metapneumovirus; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); human bocavirus; influenza A and B viruses; coronaviruses OC43, 229E, HKU-1, NL63 and SARS; parainfluenza viruses 1–4; adenoviruses; rhinovirus and enteroviruses. Pleural culture was taken if pleural fluid was present and drained. HIV was tested for according to national Cambodian guidelines advocating routine HIV testing for patients with sexually transmitted infections or TB, pregnant women and hospitalized patients suspected of being infected with HIV.

Cultures (bacterial and mycobacterial) and molecular diagnosis were processed using standard microbiological procedures and performed at the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sputum samples were validated using May Grünwald–Giemsa staining by trained laboratory staff. Only good quality samples (>25 polynuclear leucocytes and <25 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field) were sent for culture.10 Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) was performed by disc diffusion according to guidelines from the Antibiogram Committee of the French Society for Microbiology (CA-SFM/EUCAST).11 As part of the National Tuberculosis Control Program, repeated direct sputum examinations for AFB were performed at the hospital laboratories.12 Chest X-rays were reinterpreted by expert pulmonologists unaware of the final diagnosis and a review of the entire chart was done by a panel of external experts who assigned a final diagnosis to each patient, taking all clinical and diagnostic findings into account. Pneumonia was defined as lobar consolidation and alveolar or interstitial infiltrates on chest X-ray.

Bacterial isolates were considered causative when either isolated from blood or pleural fluid or if significant growth (>107 colony-forming units [cfu]/ml) was documented in a validated sputum sample with no other positive blood or pleural cultures. GNB were defined as isolation of Enterobacteriaceae or non-fermenters (Escherichia spp., Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., Pseudomonas spp., Burkholderia pseudomallei and Acinetobacter spp.). The non-GNB group included all other pathogens and CAP of unknown aetiology. Haemophilus influenzae was included in the non-GNB group.2 Patients with mixed GNB and non-GNB infections were excluded to reduce misclassification.

Underlying pulmonary disease was defined as reported chronic bronchitis or asthma, emphysema, bronchiectasis or other sequelae on chest X-ray. High alcohol consumption was defined as one or more glasses of rice wine or several daily beers. Diabetes was defined by either self-reported diabetes or glycaemia >11.0 mmol/l. An appropriate antibiotic treatment was defined as administration of at least one antimicrobial agent with in vitro activity against the identified pathogen.

Study design

Risk factors, clinical predictors and prognosis of GNB CAP were assessed comparing GNB patients with all non-GNB individuals in the total cohort. In a sensitivity analysis, patients with positive AFB were excluded. In a second sensitivity analysis, only patients with a valid respiratory sample sent for culture or who had a positive blood or pleural culture were included. This group is referred to as having a respiratory sample.

Statistical analyses

Student, Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2 or Fischer’s exact test was used, as appropriate. Logistic regression was used to assess predictors of GNB CAP and predictors of death. Variables were selected based on a priori knowledge. Variables considered for inclusion were age, sex, comorbidities, previous hospitalization or treatment (<3 weeks before admission), clinical and radiological signs and severity of disease. In the multivariable models, the definition of severity was adapted to the Cambodian setting and derived from the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI).9 A severe case was defined by the presence of at least two of the following: systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, heart rate >120 bpm, respiratory rate >30/min, oxygen saturation <90% and body temperature <35°C or >40°C.9,13 Missing data were assumed to be missing completely at random.

Variables were first assessed in univariable models and entered into multivariable models, retaining variables with p-values <0.2. The final model was derived from an initial explanatory model including all variables. Variables were then withdrawn or re-entered in a combined backward and forward selection manner.14 Models were compared using likelihood ratio tests and Aikaki’s information criterion if not nested. The final model fit was assessed by the Hesmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The area under the receiver operating characteristics curve was calculated to estimate the overall discriminatory power of the model. Likelihood ratio tests were used to test for interactions. Analyses were performed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study population and microbiology

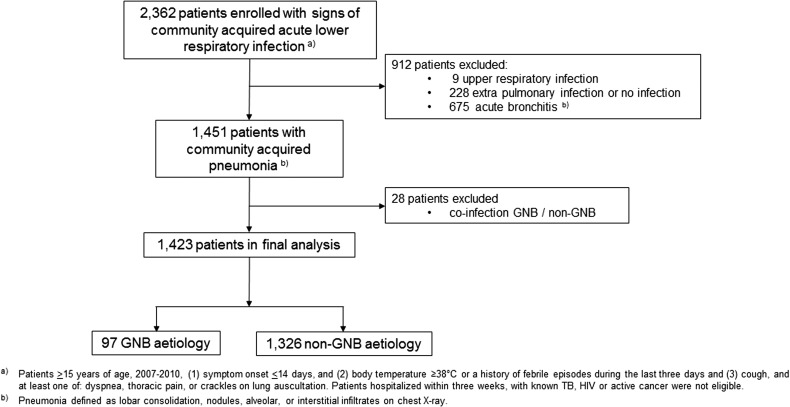

A total of 2362 patients >15 y of age were enrolled. Of these, 912 (38.6%) patients were excluded: 9 were assigned a final diagnosis of upper respiratory infection, 228 a diagnosis of extrapulmonary or no infection and 675 had a normal chest X-ray and were diagnosed as presenting acute bronchitis by the expert review panel. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the cohort selection. In all, 1451 patients fulfilled the criteria for CAP, among whom 749 (51.6%) were male, with a median age of 54 y (interquartile range [IQR] 42–66). Comorbid conditions were present in 247 (17%) of the patients. Bacterial aetiology could be assigned in 512 (35.3%) of the participants. Among these, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, H. influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, B. pseudomallei and S. pneumoniae were identified as the predominant pathogens, as previously reported.9 Blood cultures were positive in 30 (2.1%) of the patients and 44 (3%) had a viral co-infection. Valid respiratory samples were obtained from 784 (54%) of the patients.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of cohort selection, SISEA study, 2007–2010, Cambodia.

Epidemiology of GNB-associated CAP

Gram-negative bacilli were identified in 125/1451 (8.6%) of all CAP patients and 125/789 (15.8%) of the patients with respiratory sampling. The GNB pathogens identified were K. pneumoniae, 30%; B. pseudomallei, 26%; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 19%; Escherichia coli, 9%; Acinetobacter baumannii, 6% and various Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Serratia, Proteus, Enterobacter spp.), 10%. Mixed (GNB and non-GNB) infections were found in 28 (1.9%) of the patients and these patients were excluded, leaving 97 patients with GNB for further analysis.

Among patients with GNB, 27/97 (28%) had positive blood cultures. Of these, 20 had no valid sputum samples, 2 had negative sputum cultures (positive blood cultures for B. pseudomallei) and 5 had sputum cultures that matched the results from blood cultures (4 B. pseudomallei, 1 A. baumannii).

Clinical and radiological characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. In univariable analyses, patients with GNB aetiology were more likely to present with headache (21/97 [22%] vs 169/1326 [13%], p=0.01), dyspnoea (75/97 [77%] vs 900/1326 [68%], p=0.05), hypoxemia (11/97 [11%] vs 83/1326 [6%], p=0.05), high leucocyte counts (21/97 [22%] vs 141/1326 [11%], p<0.01) and severe CAP (14/97 [14%] vs 101/1326 [8%], p=0.02). Among patients with severe CAP, 14/114 (12%) had GNB. There was no significant difference in the proportion with underlying comorbidities except for diabetes, which was more common in GNB patients (8/97 [8%] vs 43/1326 [3%], p=0.01). The prevalence of GNB was 11% (14/132) in the group who reported antibiotic treatment prior to admission and 6% (83/1290, p=0.07) in the group that did not.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics in CAP patients with and without GNB, SISEA study, 2007–2010, Cambodia

| GNBa | Non-GNBb | p-Value | ORc | 95% CI | Missing information, n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 97 | 1326 | ||||

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 50 (42–61) | 55 (42–66) | 0.15 | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.0 | |

| Male, n (%) | 45 (46.4) | 689 (52.0) | 0.29 | 1.2 | 0.8 to 1.9 | |

| Smoker, n (%) | 17 (17.5) | 302 (22.8) | 0.23 | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.2 | |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 13 (13.4) | 237 (17.9) | 0.26 | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.3 | |

| Previous antibiotics, n (%) | 14 (14.4) | 118 (8.9) | 0.07 | 1.7 | 0.9 to 3.1 | |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | 54 (55.7) | 681 (51.4) | 0.41 | 1.2 | 0.8 to 1.8 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| At least 1 comorbidity, n (%) | 17 (17.5) | 226 (17.0) | 0.90 | 1.0 | 0.6 to 1.8 | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 8 (8.3) | 43 (3.2) | 0.01 | 2.7 | 1.2 to 5.9 | |

| Renal disease, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 10 (0.75) | 0.76 | 1.4 | 0.2 to 10.8 | |

| Cardiac disease, n (%) | 6 (6.2) | 138 (10.4) | 0.18 | 0.6 | 0.2 to 1.3 | |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 0 | 15 (1.1) | 0.62 | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.08) | 0.13 | 13.8 | 0.9 to 222.3 | |

| Pulmonary disease, n (%)d | 11 (11.3) | 192 (14.5) | 0.39 | 0.8 | 0.4 to 1.4 | |

| HIV, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 20 (1.5) | 0.71 | 0.7 | 0.1 to 5.1 | —e |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| CRB-65 score, n (%) | 0.93 | |||||

| 0 | 42 (43.3) | 592 (44.7) | 1 | Ref. | ||

| 1–2 | 54 (55.7) | 716 (54.0) | 1.0 | 0.7 to 1.6 | ||

| 3–4 | 1 (1.0) | 18 (1.4) | 0.8 | 0.1 to 6.0 | ||

| Severe CAP, n (%) | 14 (14.4) | 101 (7.6) | 0.02 | 2.0 | 1.1 to 3.7 | |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 75 (77.3) | 900 (67.9) | 0.05 | 1.6 | 1.0 to 2.6 | |

| Hypoxemia, n (%) | 11 (11.3) | 83 (6.3) | 0.05 | 1.9 | 1.0 to 3.7 | |

| Productive cough, n (%) | 77 (79.4) | 948 (71.5) | 0.10 | 1.5 | 0.9 to 2.5 | |

| Haemoptysis, n (%) | 12 (13.5) | 104 (8.2) | 0.09 | 1.7 | 0.9 to 3.3 | |

| Headache, n (%) | 21 (21.7) | 169 (12.9) | 0.01 | 1.9 | 1.2 to 3.2 | |

| Fever on admission, n (%) | 42 (43.3) | 459 (34.6) | 0.08 | 1.4 | 0.9 to 2.2 | |

| Lab results | ||||||

| Leucocyte count, ×109/l, median (IQR) | 10.2 (6.4–13.8) | 8.4 (6.2–11.2) | <0.01 | 1.1 | 1.0 to 1.1 | 4 |

| Leucocyte count >15×109/l, n (%) | 21 (21.7) | 141 (10.7) | <0.01 | 2.3 | 1.4 to 3.9 | 4 |

| AST, median U/l (IQR) | 26 (23–41) | 31 (24–42) | 0.15 | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.0 | 81 |

| ALT, median U/l (IQR) | 28 (21–41) | 28 (21–36) | 0.48 | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.0 | 85 |

| Creatinine μmol/l (IQR) | 89 (73–112) | 89 (77–110) | 0.39 | 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.0 | 95 |

| Radiology | ||||||

| Consolidation, n (%) | 20 (20.6) | 200 (15.1) | 0.15 | 1.5 | 0.9 to 2.4 | |

| Interstitial infiltrates, n (%) | 8 (8.3) | 203 (15.3) | 0.06 | 1.4 | 0.9 to 2.1 | |

| Alveolar infiltrates, n (%) | 65 (67.0) | 792 (59.7) | 0.16 | 0.5 | 0.2 to 1.0 | |

| Cavitation, n (%) | 30 (31.3) | 402 (30.4) | 0.87 | 1.0 | 0.7 to 1.6 | |

| Pleural effusion, n (%) | 23 (23.7) | 389 (29.3) | 0.24 | 0.7 | 0.5 to 1.2 | |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Death, n (%) | 10 (10.3) | 45 (3.4) | <0.01 | 3.2 | 1.6 to 6.7 | |

| Time to death (y), median (IQR) | 2 (0–2) | 3 (1–5) | 0.01 | |||

| Correct antibiotic, n (%)f | 12 (19.1) | 70 (81.4) | <0.01 | —f | ||

CRB-65: confusion, respiratory rate, blood pressure, 65 years of age and older; n.a.: not available; Ref.: reference.

aNon-haemophilus Gram-negative bacilli (Enterobactreiaceae, non-fermenters, Acinetobacter spp., B. pseudomallei).

bCAP from all other causes, including CAP of unknown aetiology.

cEstimated by logistic regression.

dDefined as chronic bronchitis or asthma, emphysema, bronchiectasis or other infectious sequelae on chest X-ray.

eHIV testing followed provider-initiated testing according to national Cambodian guidelines. In this cohort, 60% of the participants were tested for HIV on admission.

fCalculated in those whose bacteriology could be assigned with available data on antibiotic treatment and antibiotic susceptibility testing (n=149).

The sensitivity analyses (restricted to patients with a respiratory sample [n=789]) comparing patients with GNB and patients without GNB showed similar results to the main analyses (see supplementary appendix, Table S1).

AST and treatment

Results from AST were available for 477/691 (69%) of the samples with bacterial growth. Of the Enterobacteriaceae tested, 17/84 (20%) were resistant against third-generation cephalosporins. The majority of the B. pseudomallei and P. aeruginosa strains had a naïve susceptible pattern. Among patients with a sample with bacterial growth and results from AST, there were 149 patients with available data on the first-line antibiotic treatment: 12/63 patients (19%) with GNB had received appropriate first-line antibiotic treatment compared with 70/86 patients (81%) with a non-GNB pathogen (p<0.01).

Predictors of infections due to GNB

In multivariable analyses, severe CAP (odds ratio [OR] 1.9 [95% confidence interval {CI} 1.0 to 3.4]), headache (OR 1.8 [95% CI 1.1 to 3.0]) underlying diabetes and/or hyperglycaemia (OR 2.6 [95% CI 1.2 to 5.8]) and high leucocyte count (OR 1.9 [95% CI 1.1 to 3.3]) were independently associated with GNB aetiology (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of CAP due to GNB, SISEA study, 2007–2010, Cambodia

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 2.6 | 1.2 to 5.8 | 0.02 |

| Headache | 1.8 | 1.1 to 3.0 | 0.03 |

| Leucocyte count >15×109/l | 1.9 | 1.1 to 3.3 | 0.02 |

| Severe CAP | 1.9 | 1.0 to 3.4 | 0.05 |

Estimated by logistic regression in 1406 individuals, adjusted for all other variables in the table. The area under the receiver operating characteristics curve was 0.71.

In the sensitivity analysis, in which patients diagnosed with positive AFB (n=293) were excluded, results were similar to the main analyses with the exception of cavitation on chest X-ray, which was associated with GNB aetiology (see supplementary appendix, Table S2).

Outcome

Patients with GNB had a higher in-hospital mortality or were more likely to be discharged to die at home (10/97 [10%] vs 45/1326 [3%], p=0.01). Results from multivariate analyses are presented in Table 3. GNB, severe CAP and any underlying comorbidity were independently associated with a risk of death.

Table 3.

Predictors of mortality, SISEA study, 2007–2010, Cambodia

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNB | 3.0 | 1.4 to 6.4 | <0.01 |

| Severe CAP | 4.5 | 2.4 to 8.4 | <0.01 |

| Comorbiditya | 2.9 | 1.6 to 5.2 | <0.01 |

Estimated by logistic regression in 1423 patients, adjusted for all other variables in the table.

aAt least one of either: diabetes, renal disease, pulmonary disease, liver disease or cardiac disease.

Discussion

In this prospective observational study from two provincial hospitals in Cambodia, 8.6% of all patients with CAP had infection caused by GNB. This is likely an underestimation of the true incidence, since the proportion of GNB reached 15.8% in the population with a valid respiratory sample. Data from Cambodia are scarce. In line with our findings, however, previous studies from neighbouring countries in Asia have in general reported a high frequency of GNB regardless of age. A recent systematic review of CAP aetiology based on 48 studies from Asian countries other than Cambodia found an overall proportion of 13% in hospitalized patients. In Southeast Asia, the proportion was even higher, ranging from 14 to 27%.15

Although the reasons for the increased frequency of GNB are not fully understood, it can be explained in part by the contribution of B. pseudomallei (agent of melioidosis)—a highly pathogenic, still underrecognized agent of severe pneumonia that is endemic in Southeast Asia16,17—and the presumed high prevalence of a particularly virulent mucoid phenotype of K. pneumoniae that is prone to cause invasive disease.18,19K. pneumoniae has been shown to be among the most frequent CAP pathogens in all age groups.20–23 However, we and others have also found a high proportion of other GNB, such as P. aeruginosa, E. coli and A. baumannii.24,25

Many GNB are found in soil and humid environments. The higher incidence of GNB in CAP might therefore reflect effects of climate conditions or exposure to an environmental reservoir analogous to B. pseudomallei.4 We are aware of very few publications on the GNB nasopharyngeal carriage rate. One recent study from Indonesia reports a GNB carriage rate of 30%.26 Two older studies comparing developing and developed countries found significant differences: 36–57% vs 4–9%, respectively.27,28

It has been hypothesized that the widespread use of antibiotics (proper or substandard drugs) in Asian countries could bias the incidence estimates, since prior antibiotic use promotes colonization by GNB.15,21 Prior antibiotic use or the use of counterfeit drugs can also favour selection of patients with GNB seeking medical care due to treatment failure. We found no statistical evidence of differences in GNB prevalence between the subgroups according to prior antibiotic treatment. However, half of our cohort reported treatment of unknown origin prior to inclusion. Misclassification due to unawareness of whether or not antibiotics had been used could have biased our estimates.

We found no association with underlying comorbidity, except for diabetes. In Cambodia, access to quality health care is limited and comorbidities are likely to be underdiagnosed. A high degree of misclassification could therefore have biased estimates towards the null. Nevertheless, the prevalence of diabetes found in our study was in line with previous prevalence estimates from Cambodia.29 Furthermore, due to the substantial financial burden hospitalization often imposes on the family, many families in Cambodia choose to bring the patient home if they cannot afford care or when the patient is severely ill with little hope of recovery.17 The present study was based on hospitalized cases of CAP, which could have biased our cohort towards previously healthy and younger age groups.

While some previous studies have identified underlying pulmonary disease as a risk factor for GNB in CAP,2,30 others have not.1,7 A large proportion of our cohort had an underlying pulmonary condition. The most frequent pathogens in this group were H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae, regardless of whether the underlying condition was bronchiectasis or chronic bronchitis/asthma. Alcohol consumption was mainly associated with S. pneumoniae in our study.7

Several GNB have been shown to cause necrotic pulmonary infections and cavitary lesions on the chest X-ray.17,19 Even with the large proportion of TB cases in our cohort—a well-known phenomenon in countries with a high burden of TB—we did not observe an association with GNB. Importantly, when excluding AFB-positive patients, cavitation was significantly associated with GNB aetiology. Thus if direct sputum examination is negative, the likelihood of GNB is high in patients with cavitary lesions on the chest X-ray.

GNB has repeatedly been associated with increased severity and worse outcome in CAP.1,31 In line with previous work, we found GNB to be associated with severe CAP. Inferences about disease outcomes such as death were limited by the large proportion of patients with missing information due to transfer to other health care units. Despite this limitation, our results support previous findings that GNB are associated with worse outcome. Since the ascertainment of comorbidities was insufficient and AST information was lacking for a large proportion of our cohort, we cannot conclude whether the excess mortality could be attributed to the GNB pathogens, to differences in underlying health status or to inappropriate antibiotic treatment.

Other limitations deserve to be mentioned. Despite researchers’ efforts, it was only possible to obtain valid sputum samples from half of the patients in our study; invasive procedures such as bronchoalveolar lavage or protected specimen brush were not available. However, numerous previous studies have shown that only 30–65% of patients with CAP can produce a valid sputum sample.1,5,31 Chest X-ray was performed at admission, but no follow-up chest X-rays were performed and CT scan was not available. It was not possible to track patients who were transferred to other wards or who self-discharged against medical advice.

Determining the clinical relevance of a positive sputum sample in CAP (i.e., whether it represents true infection or just colonization) is particularly difficult with GNB since specimen collection after antibiotic exposure and many factors related to the handling of specimens often favour the growth of GNB.25,32 Nevertheless, we believe that most of the GNB isolated represent true infection. First, 28% of the patients with GNB were bacteraemic. Second, specimens were prospectively collected prior to any antibiotic treatment at the hospital. Third, only validated sputum was sent for culture and we used a cut-off of 107 cfu/ml of original sputum. Our study was based on prospectively collected information from two separate geographical regions over a 3-y period. We therefore believe the results are generalizable to the general population in Cambodia.

In conclusion, as in other Asian countries, CAP due to GNB is more common in Cambodia than in Western settings. Choosing the appropriate antibiotic is complex and further complicated by the large proportions of B. pseudomallei and by the rapidly increasing rates of antimicrobial-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Prospective clinical trials comparing empiric treatment algorithms according to the severity of CAP are therefore urgently needed. Given the complex situation, microbiological laboratory capacity needs to be increased and blood and sputum culturing in CAP should be encouraged.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Transactions online (http://trstmh.oxfordjournals.org/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions: SV, PB, CM, PC, SG, LB, MI and AT participated in study design. LB, SG, BR, VT, PLT, BG, PB, SV, ETC, PC and CM participated in data acquisition. MI, SG and AT analysed the data. MI wrote the first draft. All authors participated in critically revising the manuscript and have approved the final version.

Acknowledgements: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding: This study was part of the Surveillance and Investigation of epidemic situations in South-East Asia (SISEA) project, which was funded by the French Agency for Development and the US Department of Human and Health Services. Malin Inghammar received grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine and Swedish governmental funds.

Competing interests: None of the authors have any competing interests. Philippe Buchy is currently an employee of GSK Vaccines in Singapore.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Cambodian National Ethics Committee for Health Research (024-NECHR). Informed consent was obtained for all participants.

References

- 1. von Baum H, Welte T, Marre R et al. . Community-acquired pneumonia through Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: diagnosis, incidence and predictors. Eur Respir J 2010;35(3):598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arancibia F, Bauer TT, Ewig S et al. . Community-acquired pneumonia due to Gram-negative bacteria and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: incidence, risk, and prognosis. Arch Intern Med 2002;162(16):1849–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaplan V, Angus DC, Griffin MF et al. . Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: age- and sex-related patterns of care and outcome in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165(6):766–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown JS. Geography and the aetiology of community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology 2009;14(8):1068–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Song JH, Oh WS, Kang CI et al. . Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia in adult patients in Asian countries: a prospective study by the Asian network for surveillance of resistant pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008;31(2):107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. . Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kang CI, Song JH, Oh WS et al. . Clinical outcomes and risk factors of community-acquired pneumonia caused by Gram-negative bacilli. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2008;27(8):657–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kang CI, Song JH. Antimicrobial resistance in Asia: current epidemiology and clinical implications. Infect Chemother 2013;45(1):22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vong S, Guillard B, Borand L et al. . Acute lower respiratory infections in ≥5 year old hospitalized patients in Cambodia, a low-income tropical country: clinical characteristics and pathogenic etiology. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murray PR, Washington JA. Microscopic and bacteriologic analysis of expectorated sputum. Mayo Clin Proc 1975;50(6):339–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Société Française de Microbiologie. Comité de l’antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie Recommendation 2015. http://www.sfm-microbiologie.org/UserFiles/files/casfm/CASFM_EUCAST_V1_2015.pdf.

- 12.Cambodia TB Management Information System. http://www.cenat.gov.kh.

- 13. Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R et al. . Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58(5):377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Model-building strategies and methods for logistic regression In: Walter A, Shewhart SSW, editors. Applied logistic regression, 2nd ed New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2005; pp. 91–142. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peto L, Nadjm B, Horby P et al. . The bacterial aetiology of adult community-acquired pneumonia in Asia: a systematic review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2014;108(6):326–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meumann EM, Cheng AC, Ward L et al. . Clinical features and epidemiology of melioidosis pneumonia: results from a 21-year study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54(3):362–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rammaert B, Beaute J, Borand L et al. . Pulmonary melioidosis in Cambodia: a prospective study. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu VL, Hansen DS, Ko WC et al. . Virulence characteristics of Klebsiella and clinical manifestations of K. pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13(7):986–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rammaert B, Goyet S, Beaute J et al. . Klebsiella pneumoniae related community-acquired acute lower respiratory infections in Cambodia: clinical characteristics and treatment. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goyet S, Vlieghe E, Kumar V et al. . Etiologies and resistance profiles of bacterial community-acquired pneumonia in Cambodian and neighboring countries’ health care settings: a systematic review (1995 to 2012). PLoS One 2014;9(3):e89637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ko WC, Paterson DL, Sagnimeni AJ et al. . Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8(2):160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin YT, Jeng YY, Chen TL et al. . Bacteremic community-acquired pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: clinical and microbiological characteristics in Taiwan, 2001–2008. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prapasiri P, Jareinpituk S, Keawpan A et al. . Epidemiology of radiographically-confirmed and bacteremic pneumonia in rural Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2008;39(4):706–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Song JH, Thamlikitkul V, Hsueh PR. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia amongst adults in the Asia-Pacific region. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2011;38(2):108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ong CW, Lye DC, Khoo KL et al. . Severe community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia: an emerging highly lethal infectious disease in the Asia-Pacific. Respirology 2009;14(8):1200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Farida H, Severin JA, Gasem MH et al. . Nasopharyngeal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Gram-negative bacilli in pneumonia-prone age groups in Semarang, Indonesia. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51(5):1614–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolf B, Gama A, Rey L et al. . Striking differences in the nasopharyngeal flora of healthy Angolan, Brazilian and Dutch children less than 5 years old. Ann Trop Paediatr 1999;19(3):287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Philpot CR, McDonald PJ, Chai KH. Significance of enteric Gram-negative bacilli in the throat. J Hyg (Lond) 1980;85(2):205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. King H, Keuky L, Seng S et al. . Diabetes and associated disorders in Cambodia: two epidemiological surveys. Lancet 2005;366(9497):1633–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rello J, Rodriguez A, Torres A et al. . Implications of COPD in patients admitted to the intensive care unit by community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006;27(6):1210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Falguera M, Carratala J, Ruiz-Gonzalez A et al. . Risk factors and outcome of community-acquired pneumonia due to Gram-negative bacilli. Respirology 2009;14(1):105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bartlett JG. Diagnostic tests for agents of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(Suppl 4):S296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.