Abstract

In mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, electron transfer from NADH or succinate to oxygen by a series of large protein complexes in the inner mitochondrial membrane (complexes I–IV) is coupled to the generation of an electrochemical proton gradient, the energy of which is utilized by complex V to generate ATP. In Euglena gracilis, a non-parasitic secondary green alga related to trypanosomes, these respiratory complexes totalize more than 40 Euglenozoa-specific subunits along with about 50 classical subunits described in other eukaryotes. In the present study the Euglena proton-pumping complexes I, III, and IV were purified from isolated mitochondria by a two-steps liquid chromatography approach. Their atypical subunit composition was further resolved and confirmed using a three-steps PAGE analysis coupled to mass spectrometry identification of peptides. The purified complexes were also observed by electron microscopy followed by single-particle analysis. Even if the overall structures of the three oxidases are similar to the structure of canonical enzymes (e.g. from mammals), additional atypical domains were observed in complexes I and IV: an extra domain located at the tip of the peripheral arm of complex I and a “helmet-like” domain on the top of the cytochrome c binding region in complex IV.

Introduction

Mitochondria generate most of the energy in eukaryotic cells via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). This process can be separated in two parts: (i) the respiratory chain classically comprising four membrane protein complexes (complexes I to IV) and two mobile electron carriers, ubiquinone and cytochrome c, which together transfer electrons from reduced NADH or succinate to oxygen and establish an electrochemical proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane (proton-motive force); (ii) the ATP synthase (complex V) which works like a molecular motor that utilizes the energy of the proton-motive force across the membrane to synthetize ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate.

The NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) is one of the largest membrane protein assemblies known to date and has a central role in energy production. With an apparent molecular mass of ca. 1000 kDa, it comprises 45 subunits in mammals1, and more than 40 components in ascomycete fungi and green plants2. The bacterial complex I is made up of 14 different subunits, also present in eukaryotes. This so-called “core” complex therefore represents the minimal structural form of complex I and its subunits sum up a molecular mass of approximately 530 kDa3. The solved structures of this complex show a characteristic “L-shape” which comprises two main arms, one membrane domain in charge of the proton pumping activity and a peripheral arm involved in the electron transfer from NADH to ubiquinone4–6. The eukaryotic dimeric cytochrome bc1 complex (complex III) is composed by ten different protein subunits per monomer. Three of these subunits (cytochrome b, cytochrome c1 and the Rieske iron–sulfur protein) contain redox centers and participate in electron transfer from reduced quinone to cytochrome c. The seven supernumerary subunits are not embedded in the membrane, they are peripherally localized at the membrane surfaces and are not directly related with the catalytic activity of the complex in the electron transport chain7–9. The mammalian cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) is a multimeric enzyme formed by 14 subunits. The core subunits (Cox1, Cox2, and Cox3) are highly hydrophobic integral membrane proteins without substantial extramembrane domains. Their structure is highly-conserved in α-proteobacteria and eukaryotes. The remaining 11 mammalian accessory subunits are located surrounding the catalytic core10,11. This complex exists as a 420 kDa dimer in its crystalline state, although the fully active monomeric form can be also isolated12–14.

Euglenids are a group of free-living, single-celled flagellates that thrive predominantly in aquatic environments. Euglenids belong to the monophyletic group of Euglenozoa together with other heterotrophic flagellates like Symbiontida (free-living flagellates found in low-oxygen marine sediments), Diplonemea (free-living marine flagellates) and Kinetoplastea (free-living and parasitic flagellates, e.g. Trypanosoma)15,16. Euglena gracilis, a model organism among Euglenids, is a secondary photosynthetic unicellular eukaryote that arises from an endosymbiosis between a green alga and an ancient phagotroph euglenozoan species17,18. This flagellate has a remarkable adaptability to various environmental conditions. It can grow photoautotrophically, heterotrophically, and photoheterotrophically19 and is able to metabolize various exogenous carbon sources such as sugars, alcohols and amino acids20. E. gracilis has a mitochondrial electron transfer system constituted by the conserved OXPHOS complexes (Complexes I–V) and an alternative oxidase (AOX) sensitive to diphenylamine, salicylhydroxamic acid (SHAM), n-propylgallate and disulfiram21–23.

The subunit composition of the OXPHOS complexes among the Euglenozoa includes additional and atypical subunits together with some conserved classical ones24–27. This divergent subunit composition derives notably in an atypical structure in the dimeric ATP synthase from euglenids28,29. Additionally, the Euglena complexes I and V present higher estimated molecular masses (1.5 and 2 MDa, respectively) when compared with other eukaryotic complexes27. The consequences of atypical subunits or structural domains in the function of the respiratory-chain pathway is still enigmatic and only hypotheses have been formulated so far, such as a role in the response of E. gracilis to stress30, resistance to inhibitors27,31,32, or any specific role in the parasitic lifestyle of trypanosomes33. Regarding the last point, our group has shown that many additional subunits originally described in kinetoplastids33–37 are shared with E. gracilis. 19 of the 45 conventional subunits of the eukaryotic complex I are found in E. gracilis (ND1/4/5, NDUFS1–3/7/8, NDUFV1/2, NDUFA7/9/12/13, NDUFAB1, NDUFB7/11, NDUFC1, and CAG1/2) together with 14 trypanosomatid subunits (NDTB1/2/5/6/11/12/17/18/22/25/28/29/31/34). Amongst the 10 classical complex III subunits, eight were found in E. gracilis (QCR1/2/6/7/10, RIP1, COB, CYT1) together with two trypanosomatid subunits (QCRTB1/2). From the 13 mammalian CIV subunits, only seven subunits (COX1/2/3/5 A/5B/6B/8 A) could be identified in E. gracilis along with nine kinetoplastid subunits (COXTB1/2/4/5/6/8/10/12/16)27. So it is unlikely that these subunits play a specific role in the parasitic lifestyle but rather play a fundamental role in Euglenozoa.

In the present work, we studied the unusual subunit composition of proton-pumping respiratory complexes (i.e. complexes I, III, and IV) from Euglena gracilis in more detail and investigated the consequences of these atypical subunit compositions on the structural level by single-particle electron microscopy.

Results and Discussion

Purification of the mitochondrial complexes I, III and IV from E. gracilis

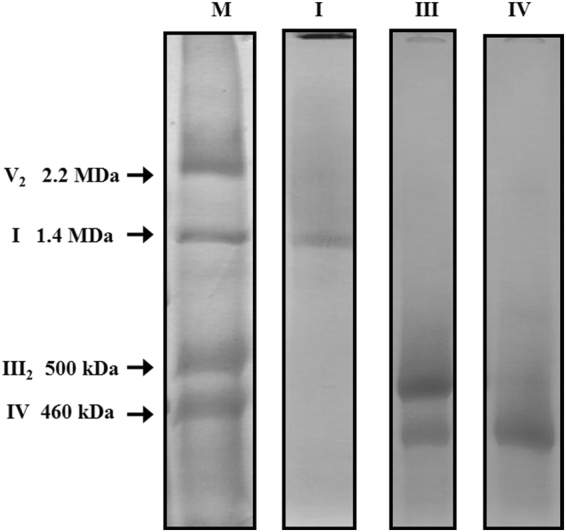

In a previous study we reported that the respiratory complexes of E. gracilis comprise many subunits which were also described in trypanosomatid respiratory complexes and, conversely, many subunits were lacking which are conserved among mammals and fungi27. In order to confirm this atypical subunit composition, we decided to further purify and characterize the subunit composition of complexes I, III, and IV. To this end, a purification protocol involving two chromatographic steps was developed (see Methods section for further details) to obtain enriched fractions of each of the three complexes. The fraction containing complex I was almost pure, as judged by the main 1.4 MDa complex observed after BN-PAGE analysis, while the fractions enriched in complex III (500 kDa) or complex IV (460 kDa) were slightly contaminated (Fig. 1 and Suppl. Information Fig. S1). It is to note the estimated molecular masses determined here are slightly different from the values previously reported27.

Figure 1.

Electrophoretic patterns of purified complexes I, III and IV from Euglena gracilis. Isolated mitochondria were solubilized with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside followed by a two-step chromatographic purification (Complete gels used are shown in Suppl Information Fig. S5). (M) Total mitochondrial proteins from Euglena gracilis. (I) purified NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) fraction, (III) enriched cytochrome bc1 complex (complex III) fraction, remaining complex IV could be observed, (IV) enriched cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) fraction. Estimated molecular masses and identities of Coomassie brilliant blue-stained protein complexes are indicated (see Suppl. Information Fig. S1 for more details).

The enriched complexes were applied to a 1D-BN/2D-glycine-SDS/3D-tricine-SDS gel system. The 3D gels thus obtained for each complex are shown in Figs 2–4. Compared to 2D BN-SDS PAGE analysis, the 3D gels offer a better resolution of the polypeptide components. The Coomassie-stained spots were excised from the gel and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). All the obtained sequences (Suppl. Information) were then analyzed in silico to search for possible homologs in protein databases (NRPS, TriTrypDB). The predicted physico-chemical properties for each subunit, such as hydrophobicity (GRAVY) and iso-electric point (IP), predicted structural features like transmembrane helices (TMH) and conserved domains (CD) were also determined by in silico approaches (Tables 1–3 and Suppl. Information). Finally, in order to investigate how the subunit composition of these complexes affects their overall structure, electron microscopy in combination with single particle analysis was performed. A total of ca. 2500–3000 raw images from each complex were recorded and analysed by electron microscopy. The particle projections from each complex were classified into several groups, out of which 8 best class averages were selected per complex (an average of 3000–4000 particles per class) (Figs 5–7). The main findings for each complex will be described and discussed in the following sections.

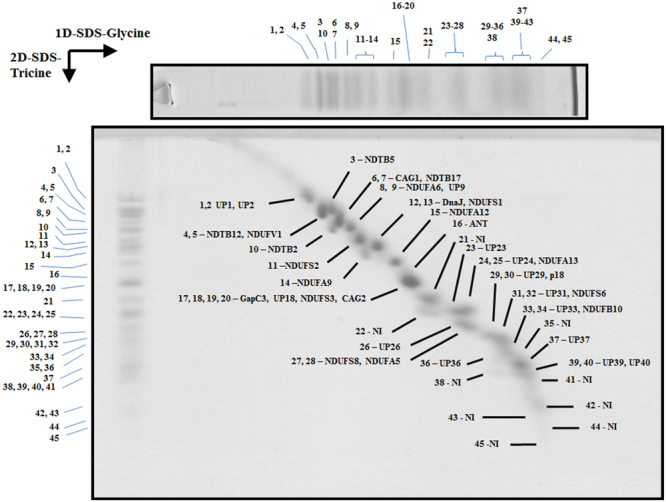

Figure 2.

3D resolution of the polypeptides that constitute the Euglena mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase. Monomeric purified complex I was resolved by BN-PAGE. The band of interest was excised and resolved in a glycine-SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide). The 2D gel was then subjected to 3D tricine-SDS-PAGE (14% acrylamide) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The identified subunits are labeled. NI, not identified; UP, unnamed protein with no homolog in other species. Details about subunit identification are given in Table 1.

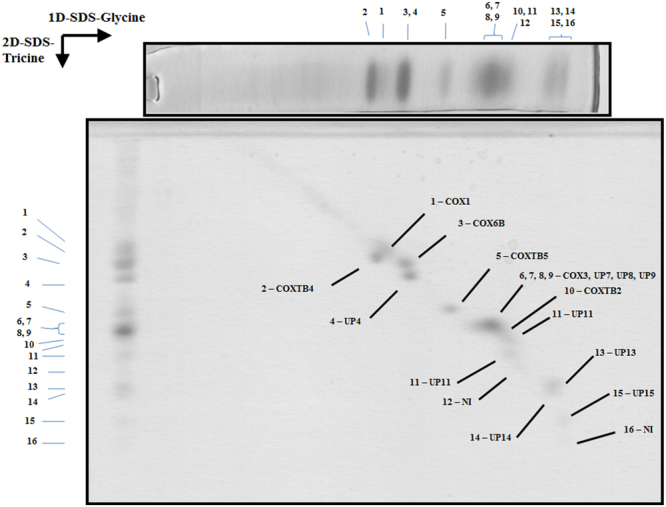

Figure 4.

3D resolution of the polypeptides that constitute the Euglena mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. Monomeric purified complex IV was resolved by BN-PAGE. The band of interest was excised and resolved in a glycine-SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide). The 2D gel was then subjected to 3D tricine-SDS-PAGE (14% acrylamide) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The identified subunits are labeled. NI, not identified; UP, unnamed protein with no homolog in other species. Details about subunit identification are given in Table 3.

Table 1.

Euglena Complex I subunits identified by mass spectrometry.

| I | Name | Accession number | MW | MW (calc) | TMH (putative) | Conserved Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | unknown | comp60085_c0_seq. 3 | 58.5 | 44.2 | 0 | —a,b |

| 2 | unknown | comp54683_c0_seq. 1 | 58.5 | 18.1 | 0 | —a,b |

| 3 | NDTB5 | comp54702_c0_seq. 3 | 52.2 | 54.9 | 1 (C) | NDUFA9_like_SDR_a (M)a,b |

| 4 | NDTB12 | >gnl|Egra|Contig2023_c | 51.0 | 51.8 | 0 | —a,b |

| 5 | NDUFV1 | comp62912_c0_seq. 6 | 51.0 | 57.8 | 0 | NADH dehydrogenase I subunit F (A)a,b |

| 6 | CAG1 | comp62122_c0_seq. 3 | 48.5 | 48.7 | 0 | LbH_gamma_CA_like (M)a,b |

| 7 | NDTB17 | comp63840_c0_seq. 1 | 48.5 | 53.3 | 0 | Adenylate forming domain, Class I (C)a,b |

| 8 | NDUFA6 | comp61975_c0_seq. 5 | 45.7 | 48.7 | 0 | —a,b |

| 9 | unknown | comp46408_c0_seq. 1 | 45.7 | 8.5 | 0 | —a,b |

| 10 | NDTB2 | comp63125_c0_seq. 1 | 44.8 | 46.4 | 0 | 2-enoyl thioester reductase (N,M)a,b |

| 11 | NDUFS2 | comp55715_c0_seq. 3_c | 41.9 | 48.6 | 1 (M) | NADH dehydrogenase subunit D; NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase 49 kD subunit 7 (A)a,b |

| 12 | DnaJ | comp60945_c0_seq. 5_c | 40.0 | 43.6 | 1 (C) | DnaJ molecular chaperone homology domain(N)a,b |

| 13 | NDUFS1 | comp61469_c0_seq. 1_c | 40.0 | 43.8 | 0 | NADH dehydrogenase/NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kD subunit (chain G) (A)a,b |

| 14 | NDUFA9 | comp59654_c0_seq. 4 | 38.7 | 41.3 | 0 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, subunit 9, 39 kDa (A)a,b |

| 15 | NDUFA12 | gnl|Egra|Contig149 | 35.7 | 23.2 | 0 | NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit NDUFA12a,b |

| 16 | ADP/ATP | comp62013_c0_seq. 2_cut_gi|109788168 | 32.4 | 28.3 | 2(C) | Mitochondrial carrier protein x 2(N,M)a,b |

| 17 | GapC3 | comp52123_c0_seq. 2_gi|125990644 | 31.0 | 37.1 | 0 | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, C-terminal domain (C)a,b |

| 18 | unknown | comp58177_c0_seq. 3 | 31.0 | 32.6 | 3(M) | —a,b |

| 19 | NDUFS3 | comp62960_c0_seq. 11 | 31.0 | 32.4 | 0 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit C (M)a,b |

| 20 | CAG2 | comp48089_c0_seq. 3_c | 31.0 | 28.8 | 0 | Gamma carbonic anhydrase-like (M)a,b |

| 21 | NI | — | 27.7 | — | — | — |

| 22 | NI | — | 26.1 | — | — | — |

| 23 | unknown | comp47716_c0_seq. 2_c | 25.5 | 24.0 | 0 | —a,b |

| 24 | unknown | comp51732_c0_seq. 5_ gi|125990596 | 25.1 | 22.6 | 0 | —a,b |

| 25 | NDUFA13 | comp59406_c0_seq. 3 | 25.1 | 22.7 | 1 (M) | GRIM-19 protein (M)a,b |

| 26 | unknown | comp52747_c0_seq. 1_c | 22.9 | 22.0 | 2 (M) | —a,b |

| 27 | NDUFS8 | comp54309_c0_seq. 4_c | 22.4 | 24.3 | 0 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit I (M)a,b |

| 28 | NDUFA5 | comp49716_c0_seq. 2 | 22.4 | 20.8 | 0 | ETC_C1_NDUFA5 (M)a,b |

| 29 | unknown | comp49825_c0_seq. 3_c | 21.3 | 19.5 | 1 (C) | —a,b |

| 30 | p18 | comp56597_c0_seq. 3 | 21.3 | 21.0 | 0 | —a,b |

| 31 | unknown | comp53986_c0_seq. 1_c | 20.9 | 18.3 | 0 | —a,b |

| 32 | NDUFS6 | comp55416_c0_seq. 4 | 20.9 | 17.1 | 0 | —a,b |

| 33 | unknown | comp41364_c0_seq. 3 | 18.8 | 17.7 | 1 (C) | —a,b |

| 34 | NDUFB10 | comp54566_c0_seq. 2 | 18.8 | 17.4 | 0 | —a,b |

| 35 | NI | — | 18.3 | |||

| 36 | unknown | comp54442_c0_seq. 1 | 17.5 | 17.2 | 1 (M) | —a,b |

| 37 | unknown | comp54200_c0_seq. 1 | 17.1 | 15.6 | 1 (N) | —a,b |

| 38 | NI | — | 16.8 | |||

| 39 | unknown | comp51611_c0_seq. 1_c | 16.3 | 14.9 | 1 (M) | —a,b |

| 40 | unknown | comp51117_c0_seq. 1 | 16.3 | 9.9 | 0 | —a,b |

| 41 | NI | — | 15.5 | — | — | — |

| 42 | NI | — | 11.7 | — | — | — |

| 43 | NI | — | 10.7 | — | — | — |

| 44 | NI | — | 8.7 | — | — | — |

| 45 | NI | — | 7.6 | — | — | — |

| Total | 1333 | 1097 |

NI not identified.

When accesion number ends with _c, the first Methionine was used for sequence analysis.

(N) Amino terminus, (C) Carboxi terminus, (M) Middle region, (A) Almost all sequence.

aCCD.

bDELTA-BLAST.

cThe e-value threshold for the blast results was 10−5.

Table 3.

Euglena Complex IV subunits identified by mass spectrometry.

| IV | Name | Accession number | MW | MW (calc) | TMH (putative) | Conserved Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | COX1 | comp60817_c0_seq. 2_c | 38.5 | 45.5 | 10(A) | Cytochrome C oxidase subunit I (A)a,b |

| 2 | COXTB4 | comp55436_c0_seq. 3_c | 36.4 | 35.6 | 0 | —a,b |

| 3 | COX6B | comp54364_c0_seq. 4 | 35.1 | 33.0 | 0 | —a,b |

| 4 | unknown | comp57506_c0_seq. 2_c | 32.6 | 31.7 | 0 | —a,b |

| 5 | COXTB5 | gi|109781798_c | 25.9 | 24.5 | 0 | —a,b |

| 6 | COX3 | comp54737_c0_seq. 2 | 22.9 | 27.3 | 3 (M, C) | Heme-copper oxidase subunit III (C)a,b |

| 7 | unknown | comp53543_c0_seq. 2 | 22.9 | 20.4 | 1 (M) | —a,b |

| 8 | unknown | comp51338_c0_seq. 1_c | 22.9 | 19.8 | 0 | —a,b |

| 9 | unknown | comp47102_c0_seq. 2_c | 22.0 | 20.3 | 1 (C) | —a,b |

| 10 | COXTB2 | comp54722_c0_seq. 3_c | 22.0 | 19.7 | 0 | —a,b |

| 11 | unknown | comp55710_c0_seq. 1_c | 20.9 | 19.9 | 1 (M) | —a,b |

| 12 | NI | — | 16.7 | — | — | — |

| 13 | unknown | comp50120_c1_seq. 1_c | 14.9 | 16.4 | 1 (N) | —a,b |

| 14 | unknown | comp48005_c0_seq. 1_c | 13.6 | 13.1 | 1 (M) | —a,b |

| 15 | unknown | comp53374_c0_seq. 4_c | 10.6 | 9.8 | 0 | —a,b |

| 16 | NI | — | 7.2 | — | — | — |

| Total | 365 | 337 |

NI not identified.

When accesion number ends with _c, the first Methionine was used for sequence analysis.

(N) Amino terminus, (C) Carboxi terminus, (M) Middle region, (A) Almost all sequence.

aCCD.

bDELTA-BLAST.

cThe e-value threshold for the blast results was 10−5.

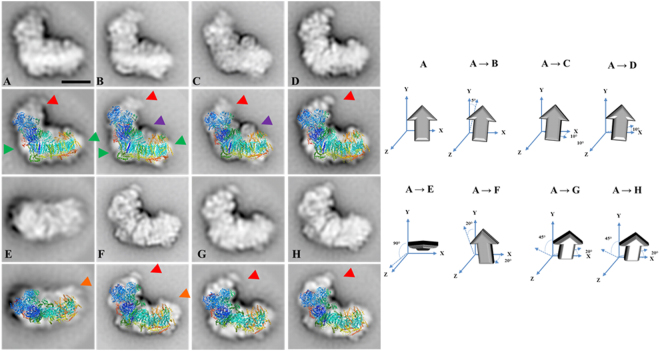

Figure 5.

2D Projection maps of purified monomeric complex I from E. gracilis obtained by single particle averaging. The monomeric complex I was purified by a two-step chromatographic procedure in the presence of β-dodecyl-n-maltoside and analyzed by EM. Overlap of the bovine respiratory complex I (pdb: 5LDW52) over the EM images was performed. (A–D) side view projections showing the characteristic “L shape” conformation. (E) upper view, (F–H) almost non-tilted from a side situation. Three unusual densities are observed: (i) an extra domain in the tip of the peripheral arm (red arrow heads), (ii) matrix-exposed protuberance attached to the membrane arm at a central position (purple arrow heads) and (iii) an extra region located in the extreme of the hydrophobic domain (orange arrow heads). At the right: schematic representation of the rotation of the complex in the left panels. The approximate rotation angles over the axis are indicated. The scale bar is 10 nm.

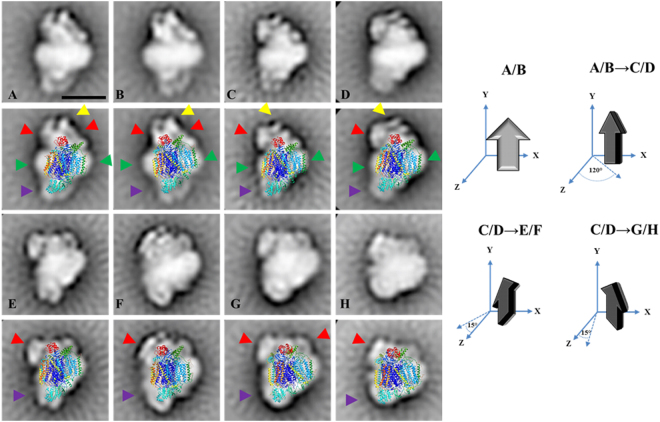

Figure 7.

2D Projection maps of purified monomeric complex IV from E. gracilis obtained by single particle averaging. The monomeric complex IV was purified by a two-step chromatographic procedure in the presence of β-dodecyl-n-maltoside and analyzed by EM. Overlap of the monomeric bovine complex together with the cytochrome c (pdb: 5IY513) over the EM images was performed. (A and B) side view projections; (C and D) ~120° rotated views from A projection along a perpendicular axis to the membrane; (E–H) slightly tilted views: the lower region is tilted by ~10–15° to the front from D projection (E, F) and the upper region is tilted by ~10–15° to the front from D projection (G, H). The membrane region is indicated by the green arrow heads, the “helmet-like” domain (see text for details) is indicated with red and yellow arrow heads, Cox5A and Cox5B positions in bovine complex IV (purple arrow heads). At the right: schematic representation of the rotation of the complex in the left panels. The approximate rotation angles over the axis are indicated. The scale bar is 10 nm.

The atypical subunits build the extra module in the peripheral arm of complex I

With the above described 3D gel system, a total of 31 spots were obtained for complex I (Fig. 2), compared to the 22 spots obtained in our previous study by 2D BN/SDS-PAGE analysis27. Ten of these spots matched for a single polypeptide, eleven matched for two peptides co-migrating, one matched for four proteins and nine spots did not lead to identification in our database. Globally, this analysis revealed the presence of at least 45 polypeptides associated to complex I, with molecular masses ranging from 7.6 to 58.5 kDa, and 36 of them were identified by MS analysis (Table 1). Six polypeptides correspond to complex I core subunits (NDUFS1/2/3/6/8, NDUFV1), eight to the α-proteobacterial ancestor (NDUFA5/6/9/12/13, NDUFB10, CAG1/2), four are Euglenozoa-specific subunits (NDTB2/5/12/17), and fourteen proteins do not present homologs and thus remain as unnamed proteins (UP). This analysis also corroborated the association of two short domains related to DNAJ and the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GapC3) enzymes [erroneously annotated as glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PD) in our previous study27]. The ANT transporter and the Euglenozoa-specific ATP synthase subunit p18 were also detected bound to complex I (Table 1, subunits 16 and 30, respectively). The ANT is rather abundant in the mitochondrial inner membrane (12% of total protein)38, and therefore we cannot exclude contamination due to hydrophobic interactions. The euglenozoan p18 subunit has been reported to be attached to the ATP synthase complex in many euglenozoan species25,27,28,39–42 and, recently, its position in the complex attached externally to the F1 sector was determined43. The reason why subunit p18 is attached to complex I is unclear. The NDTB5 subunit (subunit 3, Table 1) was previously described as a paralogous of NDUFA9 subunit27. The euglenoid subunit presents a molecular mass higher (52.2 kDa) than the conserved subunit (38.7 kDa) (subunit 14, Table 1). This homology-pair characteristic is also present in the trypanomatid enzyme44, and thus suggests that euglenoids incorporated this new subunit by gene duplication.

Overall, these first results are similar to our previous study (Suppl. Information) and thus confirm the atypical subunit composition of Euglena gracilis complex I. The sum of the molecular masses from all the identified peptides (Table 1) is 1333 kDa, which is close to the value of 1.4 MDa estimated directly by BN-PAGE (Figs 1 and Suppl. Information S1). Additional subunits might also be present in the mature complex but have probably escaped from identification (see27 for a discussion about the underlying reasons). Among those subunits not identified by mass spectrometry but previously identified at genomic level for Euglena complex27, there are subunits present in canonical complex I of mammals, fungi and plants, like highly hydrophobic core mitochondrion-encoded (NAD1, NAD4, NAD6) or nucleus-encoded (NDUFV2, NDUFA7, NDUFAB1, and NDUFB7) subunits (Suppl. Information), all inherited from the alpha-proteobacterial ancestor45. This value of 1.4 MDa for Euglena complex I contrasts with the ca. 1 MDa value described in many other organisms including mammals46,47, yeasts48,49, green algae50 or flowering plants51, and prompted us to investigate the structure of Euglena complex I.

Negatively stained complex I adopts mainly three positions on the carbon support film (Fig. 5). The first four side-view projections (panels A–D) show that complex I has an “L shape” conformation, which is in agreement with the bacterial and mitochondrial complex I structures [e.g.6,52]. The membrane arm is best seen in projections A and B (green arrow heads). The other projections correspond to the upper view (panel E) and to tilted side views (panels F–H). The comparison with the structure of bovine respiratory complex I (pdb: 5LDW52) revealed two main differences: (i) a matrix-exposed protuberance attached to the membrane arm at a central position (visible in projections B and C, purple arrow heads) and (ii) an extra domain located at the tip of the peripheral arm (panels A–D and F–H, red arrow heads). A third putative extra region is located in the distal part of the hydrophobic domain (Panels E and F, orange arrow heads). However, we cannot exclude that this density is due to the presence of detergent micelles surrounding the membrane arm. All of these features are also highlighted upon comparison with the yeast Complex I (pdf: 4WZ753) (Suppl. Information Fig. S2). The first domain (purple arrow heads) probably corresponds to the gamma-carbonic anhydrase (CAG) domain, first described in complex I from flowering plant mitochondria54 and later described in other organisms like the chlorophycean alga Polytomella sp.55 or the amoeboid protozoon Acanthamoeba castellanii56. Members of the CAG family have been identified in all eukaryotic lineages but not in Opisthokonts (i.e. mammals and fungi)56,57. In this respect, two members (CAG1-2) have been found by proteomic approach in Euglena complex I (Fig. 2 and Table 1). In contrast, the extra domain located at the tip of the peripheral arm (Fig. 5, red arrow heads) has no counterpart in the complex I structures described in representatives of other lineages. Interestingly, based on the presence of some additional subunits in trypanosomes, a fatty acid synthase (FAS) domain has been proposed as an additional complex I structural domain. Among the non-canonical subunits identified in trypanosomes35,44, NDTB2 and NDTB17 were also confirmed here as components of Euglena complex I. Neither NDTB2 nor NDTB17 subunits possess any putative transmembrane helices but comprise a functional domain related to fatty acid synthesis (FAS) (Table 1). The NDTB17 subunit presents an adenylate forming domain, a domain which has been associated with the fatty acid activation necessary for their subsequent metabolism (e.g. β-oxidation)58,59. The NDTB2 subunit presents a 2-enoyl thioester reductase domain. This enzymatic activity has been associated with the NADPH-dependent conversion of trans-2-enoyl acyl carrier protein/coenzyme A (ACP/CoA) to acyl-(ACP/CoA) in fatty acid synthesis60. NDTB2 and NDTB17 are thus good candidates to participate in a FAS domain. In trypanosomes, it was suggested that such domain is located at the interface between the membrane and matrix arms44, but no extra density can be distinguished in this area in Euglena complex I. We propose that the FAS domain is therefore located at the tip of the matrix domain in Euglenozoa (Fig. 5, and Suppl. Information Fig. S2). It should be noted that a mitochondrial small acyl carrier protein NDUFAB1/ACPM is also found associated to complex I in mammals and fungi61 but not in flowering plants51. This subunit has been found in Euglena at genome level (Suppl. Information). Altogether, these findings may indicate an ancient function related to fatty acid metabolism associated to complex I in Eukaryotes.

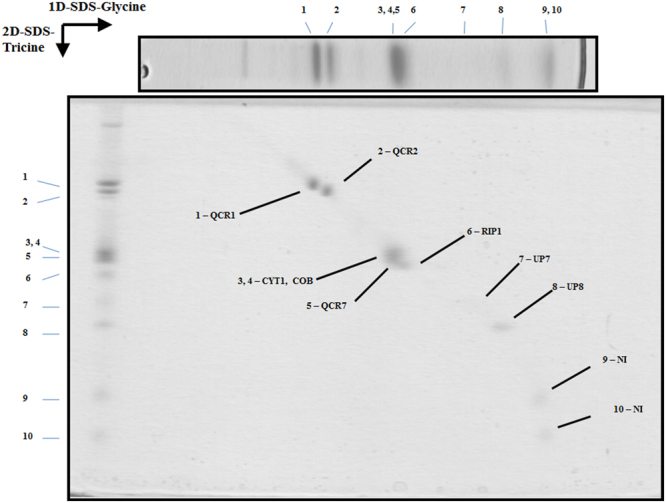

Overall conserved subunit composition and structure of Euglena Complex III

Euglena mitochondrial complex III was resolved into 10 protein spots of molecular masses ranging between 10.5 and 50.9 kDa (Fig. 3). Six corresponded to a single polypeptide in our database, one was found to comprise two different polypeptides, and two were not identified. Six of these polypeptides corresponded to canonical complex III subunits QCR1, QCR2, QCR7, CYT1, COB, and RIP1, whereas two polypeptides of about 20 kDa do not have homologs in the databases and thus remained as unnamed proteins (UP) (Table 2 and Suppl. Information). Two additional complex III canonical subunits (QCR6/10) that were previously identified at genomic level in Euglena could not be identified here (Suppl. Information). No CD could be confidently identified for the two UP proteins and only one putative additional TMH is predicted for UP7 protein (e-value threshold = 10−5).

Figure 3.

3D resolution of the polypeptides that constitute the Euglena mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex. Dimeric purified complex III was resolved by BN-PAGE. The band of interest was excised and resolved in a glycine-SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide). The 2D gel was then subjected to 3D tricine-SDS-PAGE (14% acrylamide) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The identified subunits are labeled. NI, not identified; UP, unnamed protein with no homolog in other species. Details about subunit identification are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Euglena Complex III subunits identified by mass spectrometry.

| III | Name | Accession number | MW | MW (calc) | TMH (putative) | Conserved Domainc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | QCR1 | comp63646_c0_seq. 8_c | 50.9 | 53.5 | 0 | Peptidase_M16 (N), Peptidase_M16C (C)a,b |

| 2 | QCR2/TB1 | comp60854_c0_seq. 1_c | 47.9 | 51.1 | 0 | Insulinase (Peptidase family M16) (N)a,b |

| 3 | CYT1 | comp49373_c0_seq. 3_c | 31.3 | 28.0 | 1 (C) | Cytochrome C1 family (A)a,b |

| 4 | COB | ALQ28773.1 | 31.3 | 43.9 | 9(A) | cytochrome b (A)a,b |

| 5 | QCR7 | comp51517_c0_seq. 3_c | 30.3 | 27.4 | 1 (N) | Ubiquinol-cytochrome C reductase complex 14kD subunit (C)a,b |

| 6 | RIP1 | comp57996_c0_seq. 3_c | 29.5 | 27.8 | 1 (M) | Rieske_cytochrome_bc1 (C)a,b |

| 7 | unknown | comp47102_c0_seq. 2_c | 22.4 | 20.3 | 1 (C) | —a,b |

| 8 | unknown | comp57617_c0_seq. 1_c | 18.8 | 17.6 | 0 | —a,b |

| 9 | NI | — | 14.7 | — | — | — |

| 10 | NI | — | 10.5 | — | — | — |

| Total | 288 | 270 |

NI not identified.

When accesion number ends with _c, the first Methionine was used for sequence analysis.

(N) Amino terminus, (C) Carboxi terminus, (M) Middle region, (A) Almost all sequence.

aCCD.

bDELTA-BLAST.

cThe e-value threshold for the blast results was 10−5.

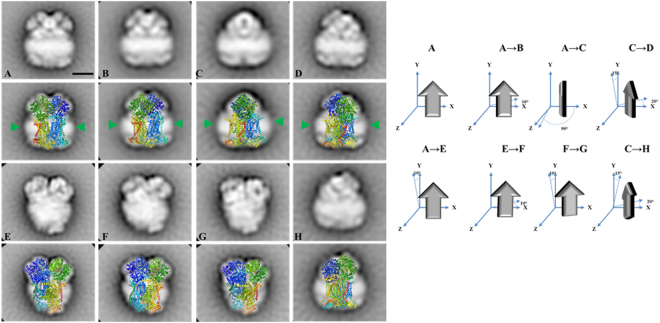

The reported structures for the eukaryotic dimeric complex III are composed of 10 to 11 subunits per monomer7,62. In Euglena, the sum of all the determined peptides (288 kDa per monomer, Table 2) is in good agreement with the size of a native dimeric complex (ca. 500 kDa, Fig. 1). The Euglena complex III particles classify into two principal groups on the carbon film (Fig. 6): Side-view projections (panels A–D) and slightly tilted side-view projections (panels E–H). The membrane region of the complex is evident in the side-view projections (Panels A–D green arrow heads). Panels A and B represent the side-by-side monomer placement, panel C represents the 90° rotation (one monomer in front of the other). The comparison with the structure of chicken dimeric complex III [pdb: 4U3F63] explains all the projections obtained and corroborates the dimeric oligomeric state of this complex. The absence of additional electronic densities from any projection concurs with the absence of extra atypical subunits. In conclusion, the overall structure of E. gracilis complex III is highly similar to the one reported for other species. However, the lack of QCR8 coding sequence in Euglena nucleotide database27 questions the complex III biogenesis in Euglena. QCR8, which has one TMH63, is required to form an early core subcomplex with COB and QCR7 during complex III biogenesis in S. cerevisiae62,64. The QCR7 subunit usually shields the quinone pocket of the CYT1 subunit from exposure to the aqueous environment on the matrix side65. Interestingly, Euglena QCR7 subunit presents an atypical N-terminal extension (~78 residues; Suppl. Information Fig. S3) with a putative TMH that may take the role of the missing QCR8 subunit. Another role for this QCR7 extension in Euglena could be to maintain the structural integrity of the quinone reduction site. Such a function has already been described for the atypical extension in the CYT1 subunit from Rhodobacter sphaeroides bc1 complex66. A subunit named QCR9 was also found in Euglena complex III by N-terminal sequencing67 even though this subunit does not correspond to the canonical QCR9 subunit described in other species27,67. Altogether, this analysis confirmed the dimeric state of the purified complex and showed no atypical domains within the overall structure.

Figure 6.

2D Projection maps of purified dimeric complex III from E. gracilis obtained by single particle averaging. The dimeric complex III was purified by a two-step chromatographic procedure in the presence of β-dodecyl-n-maltoside and analyzed by EM. Overlap of the chicken dimeric complex III (pdb: 4U3F63) over the EM images was performed. (A–D) side view projections, (E–H) slightly tilted side-view. The membrane region is indicated by the green arrow heads. At the right: schematic representation of the rotation of the complex in the left panels. The approximate rotation angles over the axis are indicated. The scale bar is 10 nm.

Atypical subunit composition of Euglena complex IV is associated to the presence of an extra domain in the cytochrome c binding region

With the current 3D gel system a total of 14 spots were obtained for Euglena mitochondrial complex IV (Fig. 4), while it was previously resolved into 10 protein spots27. A single polypeptide could be identified in our database for eleven spots, one spot matched to four polypeptides of similar molecular masses and two spots remained unidentified. Three polypeptides correspond to classical complex IV subunits (COX1, COX3, and COX6B), three to Euglenozoa-specific subunits (COXTB2/4/5), six peptides do not present any similarity with other existing proteins and therefore remain as unnamed proteins (UP) (Table 3 and Suppl. Information). Here again, no CD could be confidently identified for non-classical subunits (e-value threshold = 10−5). Globally, our analysis allowed the identification of at least 16 polypeptides associated with Euglena complex IV with molecular masses ranging from 7.2 to 38.5 kDa. The stoichiometry of one subunit per monomer was proposed based on Coomassie staining68. Accordingly, the sum of all the associated peptides (365 kDa, Table 3) is lower than the molecular mass of 460 kDa determined for the whole complex by BN-PAGE (Fig. 1). Additional subunits might have escaped identification, such as previously identified core subunit COX2 or subunits identified at genomic level in Euglena like classical subunits (COX5A/5B/8 A)27, or even some of the originally proposed kinetoplastid complex IV subunits (COXTB1/6/8/10/12/16)26. This impressive shift in molecular mass when compared to the mammalian enzyme [200 kDa46] is therefore due to additional subunits rather than to dimerization. In this respect, classification of the 460 kDa cytochrome c oxidase images obtained by single-particle analysis led to four principal groups (Fig. 7). All pictures depict asymmetric structures unlikely to be dimers: side-views (panels A and B), ~120° rotated views from A projection along a perpendicular axis to the membrane (panels C and D), and slightly tilted views (panels E–H). The membrane region of the complex is highly recognizable in the non-tilted projections (panels A–D green arrow heads). The similarity with the structure of the monomeric bovine complex together with the cytochrome c (pdb: 5IY513) was not obvious and the resulting overlays shown in Fig. 7 are subject to caution. In this regard, the opposite orientation of the complex with respect to domains located into the matrix and the intermembrane space led to more non-explained electronic densities at both side of the complex (Suppl. Information Fig. S2). Essentially, these comparisons brought two important pieces of information. They confirmed that the 460 kDa Euglena complex IV cannot be a dimer and is thus in a monomeric form. The overlays shown in Fig. 7 also highlighted a novel 5 nm extra density in the intermembrane space (red and yellow arrow heads). This extra density forms a “helmet-like” domain over the cyt c binding region. Because the projection of this extra domain varies across all the classes, we cannot exclude the possibility that in some of them this domain is not complete. For instance, the tip-like densities at the top of the domain (Fig. 7, yellow arrows) cannot be visualized on all pictures. Previous attempts to measure the in vitro oxidase activity using exogenous cyt c as electron donor revealed a specific requirement of Euglena complex IV for its endogenous cyt c68,69. This specificity was first explained by the atypical features found in the purified Euglena cyt c70 even though other species could use the Euglena cyt c as electron donor in vitro69. Our results allow us to propose that the structure of the Euglena complex IV possesses a specific cavity for its endogenous cytochrome c.

Among the supernumerary subunits described in other eukaryotic species only Cox6b, the mammalian homolog of yeast Cox12, was identified. Cox6b/Cox12 is a structural but non-essential subunit in close contact with Cox2 and Cox3 subunits in the intermembrane space region71. Other classical subunits, such as Cox5A and Cox5B that have been identified in the previous genomic survey, are located in the matrix side of the complex with no TMH (Fig. 7, purple arrow heads), meanwhile Cox8A, an isoform of the ubiquitous Cox8B72, is located in the membrane in close contact with Cox1 subunit13. Six additional TMHs can be observed in the high resolution structures of this complex13,14, they correspond to subunits Cox4I1/6A2/6 C/7A1/7B/7 C which have not been identified at genomic or proteomic level in Euglena (27 and Suppl. Information). One putative TMH is predicted in five UP sequences (UP 7, 9, 11, 13, 15). These subunits could take the place of the classical subunits inside the membrane region to maintain the overall structure of the complex. The absence of putative TMHs among the three trypanosomatid subunits (CoxTB2/4/5) and the UP4/8/15 subunits may indicate that they participate to the 150 kDa “helmet-like” domain. Altogether, our analyses indicate that the atypical subunits of the Euglena complex IV may be involved in the construction of an atypical structure whose specific role remains to be elucidated.

Concluding remarks

The analysis of the subunit composition and the structure of proton-pumping respiratory oxidases (complexes I, III, and IV) of Euglena gracilis showed that this highly divergent organism (when compared to canonical yeast and mammal models) shares many atypical subunits described in respiratory complexes of trypanosomes27. While the canonical subunits and the lineage-specific subunits maintain the overall architecture of the respiratory complexes described in yeast and mammals, the lineage-specific subunits are presumably responsible for the atypical extra domains observed in the structure of monomeric complexes I and IV. Incidentally, the presence of these extra subunits/domains probably explains the shift in the molecular mass of complexes I and IV. One protein is also shared between complexes III and IV (UP7-CIII corresponds to UP9-CIV). Although we observed minor cross-contamination after the purification steps, the fact that this polypeptide is the only found in common between both complexes may suggest that it is involved in interactions that lead to the formation of the supercomplex previously observed27. Overall, the roles of these atypical subunits/domains in enzyme activities or supramolecular associations remain to be elucidated.

Material and Methods

Algal strain, growth conditions and mitochondria isolation

Euglena gracilis (SAG 1224-5/25) was obtained from the University of Göttingen (Sammlung von Algenkulturen, Germany). Cells were grown in the dark under orbital agitation at 25 °C. Ethanol 1% was used as carbon source. The liquid mineral Tris-minimum-phosphate medium (TMP) pH 7.0 was supplemented with a mix of vitamins (biotin 10−7%, B12 vitamin 10−7% and B1 vitamin 2 × 10−5% (w/v)). The cells were collected at the middle of the logarithmic phase by a 10-min centrifugation step at 7000 × g and stored at −70 °C until use. Mitochondria were obtained by differential centrifugation following the procedure previously described28 and stored at −70 °C until use. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Biorad).

Purification of respiratory complexes

All steps were performed at 4 °C. Seventy five milligrams of mitochondrial proteins were solubilized with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM, 4 g detergent per g protein) in buffer A containing Tris-HCl 50 mM, amino caproic acid 50 mM, MgSO4 1 mM, NaCl 50 mM, glycerol 10%, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) 1 mM, tosyl-lysyl-chloromethylketone (TLCK) 50 μg/ml (pH 8.4). The mixture was incubated with gentle stirring for 30 min, and centrifuged at 38,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was diluted three times in buffer A without NaCl and supplemented with DDM 0.01%. After a filtration step (0.22 μm) the sample was loaded on an anion exchange column (Mono Q HR 5/5, 1 mL) connected to an ÄKTA explorer 100 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated with the same buffer and washed until a base line was obtained. The column was washed with 50 mM NaCl in the same buffer (10 VC) and eluted with a 50–500 mM NaCl linear gradient (40 VC). Two milliliter fractions were collected and visualized by BN-PAGE.

The samples enriched with Complex I were pooled and concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter 100 kDa (EMD Millipore) to a final volume of 500 µL and injected to a Superose 6 10/300 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) previously equilibrated with buffer A containing 200 mM NaCl and DDM 0.01%. The elution was carried out at 0.3 mL/min, 0.5 mL fractions were collected and visualized by BN-PAGE. The samples enriched with Complex I were pooled separately and stored at −70 °C until use.

The enriched fractions with Complex III and IV from the anion exchange column were pooled separately and concentrated to a final volume of 500 µL. Each fraction was injected separately to the Superose column equilibrated with buffer A containing 300 NaCl and DDM 0.01%. The elution of each injection was carried out as described above, 0.5 mL fractions were collected and visualized by BN-PAGE, the fractions enriched with each complex were stored at −70 °C until use.

Non-denaturating and denaturating protein electrophoresis

Each complex was resolved by BN-PAGE using a 3–10% acrylamide gradient gel at 4 °C. The first dimension band was then excised from the gel and submitted to a 2D/3D Glycine/Tricine SDS-PAGE carried out as in73 at room temperature. Briefly, the subunits of each complex were separated in a Glycine-SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide) and then each 2D lane was excised and separated individually in a Tricine-SDS-PAGE (14% acrylamide).

Coomassie blue-stained protein spots were manually excised from the 3D gels and analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS) as described in27. Briefly, the Matrix Laser Desorption Ionization Analyses (MALDI) was performed on a 4800 MALDI time of flight (TOF/TOF) system (Applied Bisosystems). Internal digested fragments of trypsin as well as TOF/TOF Cal Mix 5 (AB Sciex) were used as internal calibration. For direct protein identification with MASCOT against our homemade database (available in https://figshare.com/s/57d2ba4ebfbb472ae3de), protein scores greater than 60 were considered as significant (P < 0.05). To determine the molecular mass of each subunit, PageRuler plus pre-stained protein ladder (Thermo Scientific) were used as size molecular markers. The molecular mass of each protein spot was calculated from its migration distance by comparing it with the migration of molecular markers (the linear regression between the logarithm of the migration distance and the molecular mass (kDa) of the molecular markers has a R2 of 0.989).

In silico analysis of the identified subunits from the respiratory complexes

To further characterize the sequences identified by MS, each protein sequence was submitted to a tBLASTn analysis against the expressed sequence tags (EST) database from Euglena gracilis (taxid: 3039) available in the NCBI server. The obtained translated nucleotide sequences were manually assembled to generate the longest possible polypeptide. The resulting polypeptides were submitted to similarity searches by BLASTp against the non-redundant protein sequences database (NRPS) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and against the Kinetoplastid genomic resource database (TriTrypDB) (http://www.tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb/). The first methionine codon of each sequence was arbitrarily chosen as the putative start codon. The theoretical isoelectric point, molecular mass and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) were determined using the algorithm ProtParam (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/), transmembrane helixes (TMH) were predicted using Phobius server (http://phobius.sbc.su.se/) and TMHMM Server v. 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/), local conserved domains (CD) were searched using the NRPS Blastp, DELTA-Blast and Conserved Domain Blast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi), the e-value threshold for the in silico analysis results was 10−5, when a TMH or CD was found the topological localization inside the peptide was annotated. Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) was used for direct alignments of protein sequences.

Visualization of isolated complexes I, III and IV by transmission electron microscopy

5 µl of each purified complex solution was absorbed onto freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated copper grids, the excess amount of sample was blotted with filter paper and subsequently stained with 2% uranyl acetate for contrast. Imaging was performed on a Tecnai T20 equipped with a LaB6 tip operating at 200 kV. The “GRACE” system for semi-automated specimen selection and data acquisition74 was used to record 2048 × 2048 pixel images at 133,000 × magnifications using a Gatan 4000 SP 4 K slow-scan CCD camera with a pixel size of 0.224 nm. Single particles were analyzed with the Xmipp software (including multi-reference and non-reference alignments, multivariate statistical analysis and classification, as in75 and RELION software76. The best of the class members were taken for the final class-sums.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

P.C. acknowledges financial support from the Belgian Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique F.R.S.-F.N.R.S. (FRFC 2.4597, CDR J.0079) and European Research Council (H2020-EU BEAL project 682580). P.C. is a Senior Research Associate from F.R.S.-FNRS.

Author Contributions

H.V.M.A., P.C. and E.J.B. conceived the research, H.V.M.A., L.C.T., K.N.S.Y., F.B., H.D. and P.M. performed the experiments, H.V.M.A., K.N.S.Y., P.C. and E.J.B. analysed the data, H.V.M.A. and P.C. wrote the manuscript, all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-28039-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carroll J, et al. Bovine complex I is a complex of 45 different subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:32724–32727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardol P. Mitochondrial NADH:Ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) in eukaryotes: A highly conserved subunit composition highlighted by mining of protein databases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2011;1807:1390–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedrich T, et al. Redox components and structure of the respiratory NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex i) Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1998;1365:215–219. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Luca, A., Gamiz-Hernandez, A. P. & Kaila, V. R. I. Symmetry-related proton transfer pathways in respiratory complex I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 201706278 10.1073/pnas.1706278114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Baradaran R, Berrisford JM, Minhas GS, Sazanov La. Crystal structure of the entire respiratory complex I. Nature. 2013;494:443–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Efremov Rg, Baradaran R, Sazanov LA. The architecture of respiratory complex I. Nature. 2010;465:441–447. doi: 10.1038/nature09066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry EA, Guergova-Kuras M, Huan L, Crofts AR. Structure and Function of Cytochrome bc Complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:1005–1075. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zara V, Conte L, Trumpower BL. Biogenesis of the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 2009;1793:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia D, et al. Structural analysis of cytochrome bc1 complexes: Implications to the mechanism of function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2013;1827:1278–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timón-Gómez, A. et al. Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase biogenesis: Recent developments. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1–16 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.055 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Vidoni S, et al. MR-1S Interacts with PET100 and PET117 in Module-Based Assembly of Human Cytochrome c Oxidase. Cell Rep. 2017;18:1727–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis M. Structure and function of cytochrome-c oxidase. Biochimie. 1986;68:459–470. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(86)80013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimada S, et al. Complex structure of cytochrome c –cytochrome c oxidase reveals a novel protein–protein interaction mode. EMBO J. 2017;36:291–300. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo F, et al. Structure of bovine cytochrome c oxidase in the ligand-free reduced state at neutral pH. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2018;74:92–98. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X17018532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zakrys, B., Rafal, M. & Karnkowska, A. In Euglena: Biochemistry, Cell and Molecular Biology (eds Schwartzbach, S. & Shingeoka, S.) 3–28 (2017).

- 16.Burki F. The eukaryotic tree of life from a global phylogenomic perspective. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014;6:1–18. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbs SP. The chloroplasts of some algal groups may have evolved from endosymbiotic eukaryotic algae. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1981;81:193–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb46519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turmel M, Gagnon MC, O’Kelly CJ, Otis C, Lemieux C. The chloroplast genomes of the green algae Pyramimonas, Monomastix, and Pycnococcus shed new light on the evolutionary history of prasinophytes and the origin of the secondary chloroplasts of euglenids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:631–648. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita T, Aoyagi H, Ogbonna JC, Tanaka H. Effect of mixed organic substrate on α-tocopherol production by Euglena gracilis in photoheterotrophic culture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;79:371–378. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tani Y, Tsumura H. Screening for Tocopherol-producing Microorganisms and α-Tocopherol Production by Euglena gracilis Z. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1989;53:305–312. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno-Sánchez R, et al. Oxidative phosphorylation supported by an alternative respiratory pathway in mitochondria from Euglena. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2000;1457:200–210. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00102-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharpless TK, Butow RA. An inducible alternate terminal oxidase in Euglena gracilis mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:58–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benichou P, Calvayrac R, Claisse M. Induction by antimycin A of cyanide-resistant respiration in heterotrophic Euglena gracilis: Effects on growth, respiration and protein biosynthesis. Planta. 1988;175:23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00402878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales J, et al. Novel mitochondrial complex II isolated from trypanosoma cruzi is composed of 12 peptides including a heterodimeric ip subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:7255–7263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806623200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Speijer D, et al. Characterization of the respiratory chain from cultured Crithidia fasciculata. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1997;85:171–186. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(96)02823-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verner Z, et al. Malleable Mitochondrion of Trypanosoma brucei. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015;315:73–151. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez E, et al. The mitochondrial respiratory chain of the secondary green alga Euglena gracilis shares many additional subunits with parasitic Trypanosomatidae. Mitochondrion. 2014;19:338–349. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav KNS, et al. Atypical composition and structure of the mitochondrial dimeric ATP synthase from Euglena gracilis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2017;1858:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mühleip, A. W., E. Dewar, C., Schnaufer, A., Kühlbrandt, W. & Davies, K. M. In-situ structure of trypanosomal ATP synthase dimer reveals unique arrangement of catalytic subunits. PNAS10.1073/pnas.1612386114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Castro-Guerrero NA, Krab K, Moreno-Sánchez R. The alternative respiratory pathway of Euglena mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2004;36:459–469. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000047328.82733.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann D, Parthier B. Effects of Nalidixic Acid, Chloramphenicol, Cycloheximide and Anisomycin on Structure and Development of Plastids and Mitochondria in Greening Euglena Gracilis. Exp. Cell Res. 1973;81:255–268. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(73)90514-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calvayrac R, Van Lente F, Buetow RA. Euglena gracilis: Formation of Giant Mitochondria. Science (80). 1971;173:252–254. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3993.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panigrahi AK, et al. Mitochondrial complexes in Trypanosoma brucei: a novel complex and a unique oxidoreductase complex. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7:534–545. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700430-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panigrahi AK, et al. A comprehensive analysis of trypanosoma brucei mitochondrial proteome. Proteomics. 2009;9:434–450. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Acestor, N. et al. Trypanosoma brucei Mitochondrial Respiratome: Composition and Organization in Procyclic Form. Mol. Cell. Proteomics10, M110.006908 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Zíková, A., Schnaufer, A., Dalley, R. A., Panigrahi, A. K. & Stuart, K. D. The F0F1-ATP synthase complex contains novel subunits and is essential for procyclic Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Zíková A, et al. Structural and functional association of Trypanosoma brucei MIX protein with cytochrome c oxidase complex. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:1994–2003. doi: 10.1128/EC.00204-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boxer DH. The location of the major polypeptide of the ox hearth mitochondrial inner membrane. FEBS Lett. 1975;59:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Detke S, Elsabrouty R. Identification of a mitochondrial ATP synthase-adenine nucleotide translocator complex in Leishmania. Acta Trop. 2008;105:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gnipová A, et al. The ADP/ATP carrier and its relationship to oxidative phosphorylation in ancestral protist trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell. 2015;14:297–310. doi: 10.1128/EC.00238-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimi H, et al. The assembly of F1FO-ATP synthase is disrupted upon interference of RNA editing in Trypanosoma brucei. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010;40:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson RE, Aphasizheva I, Falick AM, Nebohacova M, Simpson L. The I-complex in Leishmania tarentolae is an uniquely-structured F1-ATPase. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004;135:219–222. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Zíková A, Walker JE. ATP synthase from Trypanosoma brucei has an elaborated canonical F 1 -domain and conventional catalytic sites. 2017 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720940115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duarte M, Tomás AM. The mitochondrial complex I of trypanosomatids - An overview of current knowledge. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2014;46:299–311. doi: 10.1007/s10863-014-9556-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gabaldón T, Huynen MA. Lineage-specific gene loss following mitochondrial endosymbiosis and its potential for function prediction in eukaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:144–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wittig I, Schägger H. Advantages and limitations of clear-native PAGE. Proteomics. 2005;5:4338–4346. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wittig I, Schägger H. Features and applications of blue-native and clear-native electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2008;8:3974–3990. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guerrero-Castillo S, Vázquez-Acevedo M, González-Halphen D, Uribe-Carvajal S. In Yarrowia lipolytica mitochondria, the alternative NADH dehydrogenase interacts specifically with the cytochrome complexes of the classic respiratory pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2009;1787:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nubel E, Wittig I, Kerscher S, Brandt U, Schägger H. Two-dimensional native electrophoretic analysis of respiratory supercomplexes from Yarrowia lipolytica. Proteomics. 2009;9:2408–2418. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardol P, et al. Higher plant-like subunit composition of mitochondrial complex I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: 31 Conserved components among eukaryotes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2004;1658:212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klodmann J, Sunderhaus S, Nimtz M, Jansch L, Braun HP. Internal Architecture of Mitochondrial Complex I from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2010;22:797–810. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.073726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu J, Vinothkumar KR, Hirst J. Structure of mammalian respiratory complex I. Nature. 2016;536:354–358. doi: 10.1038/nature19095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zickermann V, et al. Mechanistic insight from the crystal structure of mitochondrial complex I. Science (80). 2015;347:44–49. doi: 10.1126/science.1259859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dudkina NV, Eubel H, Keegstra W, Boekema EJ, Braun H-P. Structure of a mitochondrial supercomplex formed by respiratory-chain complexes I and III. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:3225–3229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sunderhaus S, et al. Carbonic anhydrase subunits form a matrix-exposed domain attached to the membrane arm of mitochondrial complex I in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6482–6488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gawryluk RMR, Gray MW. Evidence for an early evolutionary emergence of gamma-type carbonic anhydrases as components of mitochondrial respiratory complex I. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cardol P, Forti G, Finazzi G. Regulation of electron transport in microalgae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2011;1807:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmelz S, Naismith JH. Adenylate-forming enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watkins PA. Fatty acid activation. Prog. Lipid Res. 1997;36:55–83. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(97)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Airenne TT, et al. Structure-function analysis of enoyl thioester reductase involved in mitochondrial maintenance. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;327:47–59. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00038-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carroll J, Fearnley IM, Shannon RJ, Hirst J, Walker JE. Analysis of the Subunit Composition of Complex I from Bovine Heart Mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2003;2:117–126. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300014-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith PM, Fox JL, Winge DR. Biogenesis of the cytochrome bc 1 complex and role of assembly factors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2012;1817:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hao G-F, et al. Rational Design of Highly Potent and Slow-Binding Cytochrome bc1 Inhibitor as Fungicide by Computational Substitution Optimization. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13471. doi: 10.1038/srep13471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zara V, Palmisano I, Conte L, Trumpower BL. Further insights into the assembly of the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex based on analysis of single and double deletion mutants lacking supernumerary subunits and cytochrome b. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:1209–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cocco T, et al. Structural and Functional-Characteristics of Polypeptide Subunits of the Bovine Heart Ubiquinol - Cytochrome-C Reductase Complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;195:731–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Esser L, et al. Inhibitor-complexed structures of the cytochrome bc1 from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:2846–2857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cui J-Y, Mukai K, Saeki K, Matsubara H. Molecular Cloning and Nucleotide Sequences of cDNAs Encoding Subunits I, II, and IX of Euglena gracilis Mitochondrial Complex III. J. Biochem. 1994;115:98–107. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brönstrup U, Hachtel W. Cytochrome c oxidase of Euglena gracilis: Purification, characterization, and identification of mitochondrially synthesized subunits. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1989;21:359–373. doi: 10.1007/BF00762727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Collins N, Brown RH, Merrett MJ. Oxidative phosphorylation during glycollate metabolism in mitochondria from phototrophic Euglena gracilis. Biochem J. 1975;150:373–377. doi: 10.1042/bj1500373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pettigrew GW, Leaver JL, Meyer TE, Ryle aP. Purification, properties and amino acid sequence of atypical cytochrome c from two protozoa, Euglena gracilis and Crithidia oncopelti. Biochem. J. 1975;147:291–302. doi: 10.1042/bj1470291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghosh A, et al. Mitochondrial disease genes COA6, COX6B and SCO2 have overlapping roles in COX2 biogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:660–671. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goldberg A, et al. Adaptive evolution of cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIII in anthropoid primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5873–5878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931463100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Colina-Tenorio L, et al. Subunit Asa1 spans all the peripheral stalk of the mitochondrial ATP synthase of the chlorophycean alga Polytomella sp. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2016;1857:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oostergetel GT, Keegstra W, Brisson A. Automation of specimen selection and data acquisition for protein electron crystallography. Ultramicroscopy. 1998;74:47–59. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(98)00022-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scheres SHW, Núñez-Ramírez R, Sorzano COS, Carazo JM, Marabini R. Image processing for electron microscopy single-particle analysis using XMIPP. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:977–990. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scheres SHW. RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.