Abstract

Objectives

Frail and disabled individuals such as assisted living residents are embedded in “care convoys” comprised of paid and unpaid caregivers. We sought to learn how care convoys are configured and function in assisted living and understand how and why they vary and with what resident and caregiver outcomes.

Method

We analyzed data from a qualitative study involving formal in-depth interviews, participant observation and informal interviewing, and record review. We prospectively studied 28 residents and 114 care convoy members drawn from four diverse assisted living communities over 2 years.

Results

Care convoys involved family and friends who operated individually or shared responsibility, assisted living staff, and multiple external care workers. Residents and convoy members engaged in processes of “maneuvering together, apart, and at odds” as they negotiated the care landscape routinely and during health crises. Based on consensus levels, and the quality of collaboration and communication, we identified three main convoy types: cohesive, fragmented, and discordant.

Discussion

Care convoys clearly shape care experiences and outcomes. Identifying strategies for establishing effective communication and collaboration practices and promoting convoy member consensus, particularly over time, is essential to the creation and maintenance of successful and supportive care partnerships.

Keywords: Care networks, Long-term care, Informal care, Formal care, Qualitative methods

Although most care for frail older persons in the United States is provided informally by family, friends, and neighbors, it often is paired with formal care, especially when the recipient is advanced in age and has a long-term physical condition or dementia (National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP, 2015). As individuals and families traverse the spectrum of long-term care, including in private homes and residential settings, they must negotiate a myriad of care needs. Yet, studies frequently focus on informal or formal care rather than their intersection, involve individual caregivers or recipients and occasionally dyads rather than entire care networks, and adopt cross-sectional rather than longitudinal methods (Kemp et al., 2017). Consequently, existing research has not fully addressed the complexity and dynamics of care for older adults.

We address this knowledge gap by providing an in-depth understanding of how residents receive care over time in assisted living. Our research is situated within and relevant to literature on family life and social relationships, informal and formal care and their intersection, and applicable across care settings. Drawing on existing critiques of research on informal-formal care intersections (Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003), we examine care relationships using the “convoy of care” model (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013). Past research and conceptual models, such as Cantor’s (1991) hierarchical compensatory model, the substitution model (see Greene, 1983), and Litwak’s (1985) task specificity model, address care complexity, but treat formal and informal care as separate spheres or overlook surrounding social, economic, and structural contexts (Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003).

Kemp et al.’s (2013) model extends Kahn and Antonucci’s (1980), “Convoy Model of Social Relations,” which conceptualizes individuals as embedded in “convoys” of close personal relationships that evolve over time and are “vehicles through which social support is distributed or exchanged” (Antonucci, 1985, p. 96). The modified model incorporates formal caregivers and suggests that long-term care recipients are situated within care convoys defined as “the evolving community or collection of individuals who may or may not have close personal connections to the recipient or one another, but who provide care…” (Kemp et al., 2013, p. 18).

Multilevel contexts influence care, including policies and resources at the federal, state, and community levels and those factors operating within care settings, networks, and relationships (Kemp et al., 2013). Assisted living, for example, is regulated at the state level and is a setting where most care is provided by unlicensed care aides (Ball et al., 2010; Dill, Morgan, & Kalleberg, 2012). Home health and hospice services are a growing presence (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016). Assisted living’s social approach to care relies on resident self-care and informal caregiver contributions, which are vital to meeting residents’ needs (Ball et al., 2005). Typically, family members and friends provide socioemotional support, assistance with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and care oversight (Gaugler & Kane, 2007; Perkins et al., 2013; Zimmerman et al., 2013).

Assisted living research identifies informal care networks with a primary person and those with shared responsibilities (Ball et al., 2005). Little else is known about how informal caregivers organize themselves over time in the context of formal care (see Gaugler, 2005), but research reveals some general informal care patterns within families. Studies show, for example, that families range from individualistic to collectivist in their approach to caregiving (Pyke & Bengtson, 1996) and that high within-family consensus about care recipient behaviors influences family dynamics and perceptions of burden (Pruchno, Burant, & Peters, 1997). Research also shows caregiving responsibilities within sibling networks can be unevenly distributed by employment and family status, proximity, and gender (Connidis & Kemp, 2008) and highlights distinct caregiving approaches by gender (Matthews, 2002). Corcoran’s (2011) research among individuals caring for a family member with dementia demonstrates distinct caregiving styles: (a) facilitating; (b) balancing; (c) advocating; and (d) directing. This typology incorporates the dynamic and complex nature of caregiving through an examination of intentions and strategies, but not how care is experienced by multiple caregivers within care networks.

Existing research provides important insights into care, but no known research involves entire care convoys studied systematically over time. Seeking to advance knowledge of care relationships and processes, our goal is to obtain in-depth understanding of residents’ care convoys in assisted living. We seek to: (a) understand care convoy patterns, including their structure and function; and (b) identify how and why convoys vary and with what resident and caregiver outcomes.

Design and Methods

We present analysis of data collected for the qualitative longitudinal study, “Convoys of Care: Developing Collaborative Care Partnerships in Assisted Living.” The overall goal was to learn how to support informal care and care convoys in assisted living in ways that promote residents’ ability to age in place with optimal resident and caregiver quality of life. An in-depth consideration of our methods appears elsewhere (Kemp et al., 2017). The study was guided by principles of grounded theory methods, which involves a constant comparison approach whereby data collection, hypothesis generation, and analysis occur simultaneously (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Building cumulatively on previous grounded theory research, the Convoy of Care model provided “sensitizing concepts” and a “place to start, not end” (Charmaz, 2007, p. 17 emphasis original) for our study. For instance, the model conceptualizes care as a process influenced by multilevel factors and calls for a holistic and longitudinal approach to studying care. We report on data collected between September 2013 and October 2015 in four assisted living communities purposively selected to maximize variation (Patton, 2015) in size, location, ownership, resident characteristics, fee structure, and availability of a dementia care unit (DCU). [Georgia State University]’s Institutional Review Board approved the study. For anonymity, we use pseudonyms for sites and participants.

Settings and Sample

Our first site, Hillside, family-owned and rural, was licensed for 11 residents, all White. Garden House had a separate DCU and was family-owned, in a small town, and licensed for 54 residents; the majority were White. Feld House, foundation-run and licensed for 46 residents, almost all Jewish, was suburban and had an extra care area, but no DCU. Oakridge Manor, licensed for 92 residents, all African American, was corporately owned and had a DCU.

Prior to entering sites, we distributed letters to residents, families, and staff and posted flyers with researcher names and photos. Across sites, we recruited 28 focal residents purposively selected to provide information-rich cases (Patton, 2015) that reflected variation in personal characteristics (e.g., age, marital status, family ties), functional status, and health conditions, factors expected to influence convoy structure, function, and adequacy. Residents ranged in age from 58 to 96 years, with a median of 85. The majorities were women (64%), White (64%), and widowed (68%) and had some college or a college degree (64%).

Formal and informal caregivers were selected based on their involvement in and knowledge of resident care. We enrolled as many individuals as possible, resulting in 114 convoy participants, including 5 assisted living executive directors and 24 staff, 20 external care workers, and 65 informal caregivers.

All executive directors were women between 38 and 59 years. Most had some college education. Staff included nursing or resident relations personnel (17%), care aides (42%), activity personnel (25%), and maintenance and transportation workers (8%). They were between 24 and 72 years. The majority were women with some college. Over half were African American.

External care workers included medical doctors (15%), hospice workers (20%), nurses (20%), therapists (35%), and a private care aide (5%). Three-quarters were women; over half were White. All had at least some college. Informal caregivers (n = 65) were residents’ family and friends, including spouses (3%), children (46%), siblings (9%), grandchildren (9%), other kin (20%), and friends and volunteers (12%). Most were women (71%) and White (83%); 79% had a college degree, 66% were married, and 46% were retired or unemployed.

Data Collection

Investigator-led teams of trained gerontology and sociology researchers collected data. During the first month, we began participant observation and conducted in-depth interviews with executive directors to learn about the community. Next, we began recruiting focal residents and convoy members; convoy member recruitment was ongoing over the 2 years. We used National Institutes of Health (2009) guidelines to assess residents’ informed consent capacity. For those unable to consent, we used proxy consent from legally authorized representatives and assent procedures (Black, Rabins, Sugarman, & Karlawish, 2010). All interviews occurred at a time and place of participants’ choosing and, except for a sibling pair and three married couples, were conducted one-on-one. Interviews ranged from 30 to 330 min, with a mean of 98; resident interviews lasted longer than other interviews, with a mean of 168 min.

In-depth interviews with residents typically occurred over multiple sittings (ranging from 2 to 8) and addressed their lives, relationships, past and present care needs and arrangements, including self-care, and experiences. Convoy member interviews inquired about relationships with the resident, care roles, responsibilities, and experiences.

Site visits occurred one to three times weekly, depending on home size. To capture the full range of care activities, we varied visits by time and day of the week. Participant observation took place in residents’ rooms, with permission, and in common areas and during mealtimes and activities. We made 809 visits and logged 2,225 observation hours, all recorded in fieldnotes.

After completing formal interviews with focal residents and staff, researchers followed up weekly, collecting data prospectively. We attempted twice-monthly follow-up with at least one informal caregiver per convoy to assess changes in care needs and arrangements. Facility record review provided data about diagnoses, medications, care plans, service agreements, doctor visits and orders, and adverse events.

Analysis

We used NVivo 10 to store, manage, and facilitate coding and analysis of all qualitative data. Initially, we coded data with broad concepts driven by research aims (e.g., “care interactions,” “convoy properties,” “life transitions”). We used intercoder comparison queries to achieve consistency. As data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously, all 18 researchers engaged in data collection, coding, and analytic discussions. The higher-order analysis described in the following paragraph was conducted by the authors. An in-depth account of our analytic processes appears elsewhere (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, forthcoming).

Following Corbin and Strauss (2015), we used a three-stage coding process. First, we examined the data for concepts based on our questions about convoy patterns through open coding. Initial codes included, for example, “primary informal caregiver,” “shared responsibility,” “collaboration,” “leadership,” and “consensus.” Through axial coding, we related initial and other categories using a paradigm (i.e., set of questions) denoting “conditions,” “actions-interactions,” and “outcomes” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 153, 156). We created analysis charts that noted, for example, connections between residents’ receipt of timely and appropriate care and staff, external worker, informal caregiver, and resident influences and convoy properties. Finally, we refined and integrated concepts into a conceptual scheme through selective coding, organized around our core category, “maneuvering together, apart, and at odds.” Evoking images of navigation in our data, the core category links subcategories in our explanatory scheme to characterize the dynamic and variable patterns and processes associated with care convoys.

Results

Maneuvering Together, Apart, and at Odds

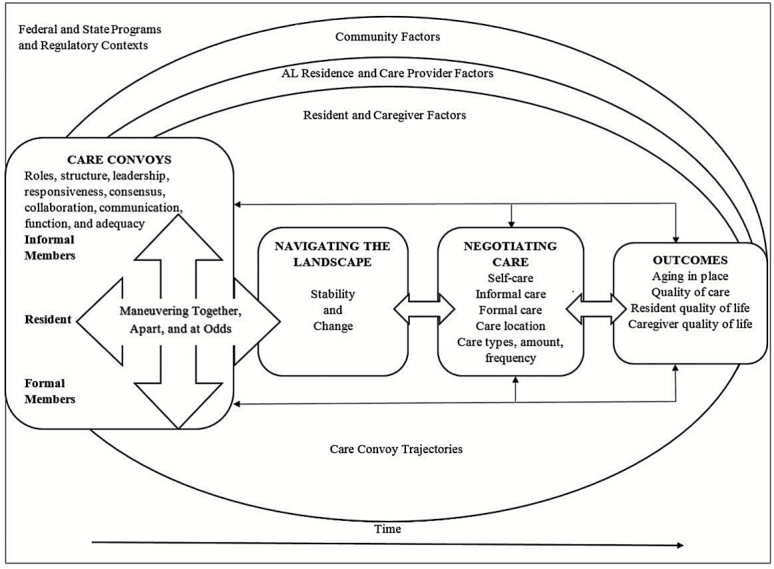

Represented in Figure 1, our core category—maneuvering together, apart, and at odds—reflects the variable ways convoy members navigated the care landscape and negotiated care needs, roles, relationships, and arrangements in an ongoing way and during times of crises. Figure 1 presents the care process as organized, but as our data show, the realities of care were not always so orderly. Care convoys varied in structure, function, and adequacy across and within convoys over time. Each had a trajectory unique in direction and duration, marked by stability and change related to resident and convoy members’ involvement, and punctuated by the timing and sequencing of events, transitions, and turning points (see Elder, 1998) in the care process. As Figure 1 shows, the ways convoys maneuvered were influenced by convoy structure and function, including leadership effectiveness and responsiveness of convoy members, and levels of consensus, collaboration, and communication within convoys, all of which were shaped by the intersection of regulatory, community, assisted living setting, convoy, and individual factors. How convoys maneuvered influenced residents’ ability to age in place and care quality and their own and caregivers’ quality of life. The three ways of maneuvering—together, apart, and at odds—align with three types of care networks identified in the data: cohesive, fragmented, and discordant. We discuss each below in the section, “Convoy Types”, but first we explain care convoy composition and care roles, as both influenced how convoys maneuvered while navigating the care context and negotiating care processes and relationships.

Figure 1.

Maneuvering together, apart, and at odds.

Care Convoy Composition and Care Roles

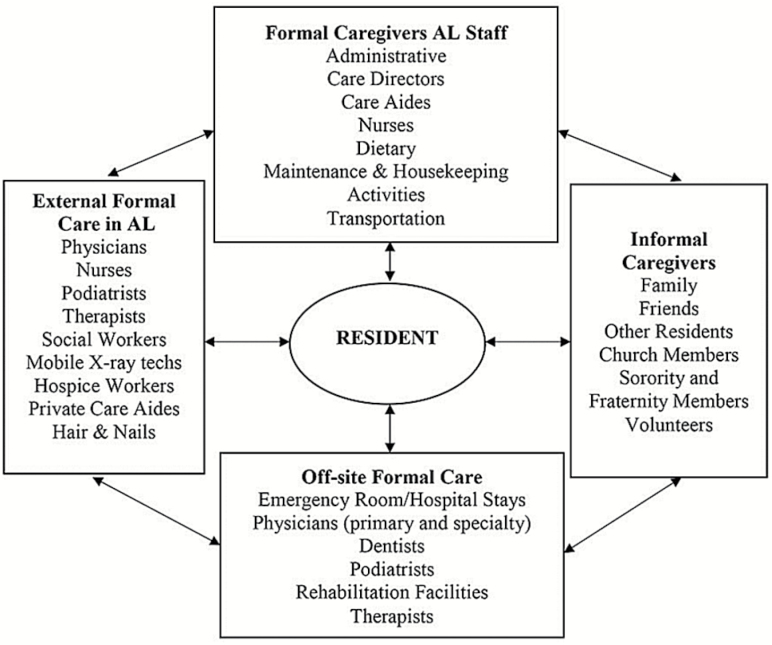

The 28 focal resident care convoys were made up of varying, and often fluctuating, numbers of informal and formal members who provided a range of care activities, also changeable, over time. Figure 2 shows the types of caregivers identified across convoys. Residents, as the center of their convoys, were part of the care process. Although children participated in 21 of the 28 convoys, 4 focal residents had no children and 3 had uninvolved children. Other family caregivers included spouses, siblings, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, and daughters and sons-in-law. Non-kin convoy members were friends, neighbors, ministers, fraternity and sorority members, volunteers, and fellow residents. In what follows we examined the contributions of each convoy member type to enhance understanding of how care convoys operate in assisted living and with what outcomes over time.

Figure 2.

Convoys of care contributors in assisted living.

Resident involvement

The self-care ability of focal residents varied widely, determined by their changing health status, care needs, functional and cognitive ability, care preferences, support from caregivers, access to assistive devices, and the structure of physical environment. The majority of focal residents needed help with three or more ADLs (57%) and IADLs (82%) and with medications (75%). Most (79%) reported their health as “good” or “fair”; 82% used an assistive device, including a walker (61%), wheelchair (39%), or both (29%); 33% had cognitive impairment. Although most performed some self-care, residents ranged in abilities, from Naomi, a Hillside resident with substantial cognitive impairment who could carry out none, to Ethel at Oakridge Manor, who, as the only focal resident who led her own convoy, assumed primary responsibility for care provision, oversight, and coordination.

Informal care

Informal caregivers were integral members of almost all convoys, and, based on our interviews and observations, were knowledgeable about or directly involved in resident care on an ongoing basis, for respite, or during crises. Although 65 were formally interviewed, data collection yielded information on 210 informal caregivers.

As with resident self-care, informal support varied and typically included most IADL and occasional ADL assistance, care monitoring and coordination, and socioemotional support. Executive directors characterized informal involvement as a “spectrum” from daily to minimal. Garden House’s owner noted: “All families are different. One fellow’s just got his daughter and she’s pretty much the primary caregiver. Some folks have multiple children that visit. Generally, some kids live out of town and they visit when they can.”

Informal convoys varied in size (from 3 to 26 members with an average of 7.5) and configuration. We distinguished between convoys with a primary caregiver, who provided all or most informal care, and those with shared responsibilities. Sixteen focal residents had convoys with a primary caregiver, 12 were children (8 daughters, 4 sons), one spouse, one sibling, one niece, and one friend. Most lived locally and had other convoy members who provided periodic regular support or intermittent respite.

In 12 convoys, informal responsibilities were shared. Shared convoys tended to be larger and more diverse than those with a primary caregiver and included the largest with 26 informal members (12 kin and 14 non-kin); half had nontraditional caregivers (i.e., no children or spouses). Generally, shared convoys, partly because of size, were more likely fraught with challenges for residents and convoy members, especially assisted living staff and administrators. Sharing of responsibilities, though, could lessen caregiver burden.

Formal care

Assisted living staff furnished the typical services of ADL and medication assistance, monitoring and oversight, housekeeping, nutrition, and activity programing. Three residences offered transportation to medical appointments for a fee; one provided shopping services. All four had a “point person” who supervised and coordinated resident care. Oakridge Manor’s care director explained the importance of this position, “It’s a very difficult decision to move into assisted living, so helping [residents and families] navigate and maneuver through assisted living, coordinating with third party providers, so whether it’s hospice or home health, knowing when it’s time to coordinate, [my] job entails that.” Complex health care called for convoy members capable of understanding and managing multiple care components.

Formal caregivers from the external community provided care, on- and off-site. Privately paid care aides, used infrequently, largely because of cost, enhanced aging in place and quality of care and life. Health care providers, including physicians, nurses, dentists, podiatrists, x-ray technicians, and various home health and hospice professionals, visited all homes. For 15 focal residents, across all sites, virtually all health care occurred in-house. A nurse practitioner who visited Feld explained, “For some people, we truly are now their primary care provider.” Eleven focal residents received almost all care off-site; two had a mixture. Off-site care required greater effort arranging appointments and transportation, tasks typically shared by residents, informal caregivers, and assisted living staff.

The majority (71%) of focal residents were hospitalized during data collection, 12 multiple times; 4 were in rehabilitation facilities and 20 had home health services. Garden House’s director described a common pattern following a resident’s hospitalization, “[Angela] ended up in a rehab unit. . . .When she comes back, they’ll have home health, physical therapy, and probably occupational therapy.” Hospice services were used by five focal residents and across settings. At Hillside, most residents, including all three focal residents, received hospice.

Convoy Trajectories: Stability and Change

Care convoys were marked by stability and change in membership and in type and level of care, resulting in unique convoy and care trajectories. Residents’ health changes triggered temporary or permanent modifications in self-care and the nature, amount, and sources of support utilized. Some transitions were anticipated (e.g., gradual decline or improvement); some were not (e.g., falls or sudden illness). Changes in informal caregivers’ lives initiated temporary or permanent transitions in convoy structure, function, and adequacy. Four informal caregivers died during the study, creating notable voids in residents’ lives. Travel, employment, health, and other family responsibilities were frequent (Kemp et al., 2017) with effects reverberating within convoys. As noted, changes in residents’ health status also caused shifts in formal convoy members and often temporary relocations to other care settings. All convoys experienced change.

Convoy Types

Care roles and structures provide an important entry point for understanding care, but do not account fully for convoy function and outcomes. Our analysis identified components consequential to the function and adequacy of care networks over time: levels of consensus surrounding care plans and goals; degree of collaboration to achieve goals; leadership effectiveness; communication quality; and responsiveness. We classified convoys as cohesive, fragmented, or discordant based on the pattern that dominated each care network over the 2-year study period. Yet, reflecting the reality, dynamism, and complexity of care arrangements and relationships, types were not mutually exclusive. For example, some convoys were cohesive for the majority of time, but had periodic or “situational” fragmentation or discordance resulting from health or convoy transitions (e.g., resident illness or decline in caregiver participation) and led to a temporary lack of coordination or disagreement about care needs, goals, and plans.

Cohesive convoys

We categorized 22 of the 28 convoys (79%) as cohesive. In cohesive convoys, the most supportive for residents and caregivers, care partners had clearly defined care goals, unified efforts, and maneuvered the care process together. Identifying and achieving goals required agreement, collaboration, and effective communication among convoy members. Setting goals involved a formal or informal member initiating dialogue. Garden House’s care coordinator noted, “My new thing . . . is getting residents to think about their goals for their time here. Is it to live as long as possible or is it to live with the best quality of life with the time you have left?”

Cohesive convoys possessed well-defined informal leadership, responsive members, and clear directives for health and financial matters. Hillside’s owner described a common pattern:

. . . you have some where there’s one power of attorney (POA), but they say, “If you can’t get me, call them” because they’re such a close family. Those are the ones that really work with you more, because you have more people to try to get, if you’re needing to get somebody quickly.

In cohesive convoys, collaboration and cooperation were successful, mainly through ongoing, open, and effective communication. Hillside’s owner observed about families: “For the most part, especially if they’re here a lot, they see what we see, and so we’re always on the same page.” Naomi’s daughter, who shared responsibility with her siblings in a cohesive convoy, said, “We are 100 percent in agreement on all of mother’s care.” Naomi remained at Hillside, despite significant decline, in part because of shared and continuous family involvement and convoy cohesiveness.

The majority (64%) of cohesive convoys had a primary informal caregiver who assumed the leadership role. Although this configuration typically fostered cohesiveness and good outcomes for residents and caregivers, other factors could intervene. For example, Carl, whose mother had high physical and emotional need, had minimal support from his wife and one out-of-state brother. Initially Carl often managed daily visits with minimal burden, but a job change with travel decreased his involvement and his mother’s satisfaction.

Shared responsibility offered more options, opinions, and potential for conflict, but Feld’s Resident Services Director emphasized that if roles were “clear cut then it’s easy, but if it’s not decided amongst them then it’s harder.” When convoy members were mutually “responsive” to requests and cohesive, shared convoys functioned effectively and had good outcomes with residents feeling supported and able to age in place and caregivers experiencing support and satisfaction with their roles. In Ethel’s informal convoy, the largest with 26 members, her leadership (described in the section on resident involvement) enhanced cohesiveness.

Fragmented convoys

Fragmented convoys had some consensus about care goals but minimal communication, collaboration, or cooperation among care partners. We categorized 4 of the 28 convoys as fragmented. One had a primary caregiver; in three, informal responsibilities were shared among multiple members.

Because fragmented convoys typically lacked informal leadership, the assisted living “point person” often assumed care coordination. For Ernest, a resident at Oakridge Manor whose informal care was shared among a niece who lived out of state and 14 non-kin members, the resident director helped coordinate medical appointments. Convoy member responsiveness and resident involvement also could help overcome informal leadership deficits in fragmented convoys. With well-established roles, fragmented convoys generally could meet residents’ needs, including a Garden House resident, Fred, whose children “all help one way or another.” Yet, because they lacked close relationships, his children did not coordinate or communicate regularly. Illness, hospitalization or a change in caregiver availability could strain these potentially fragile convoys, often impacting care quality. Health crises though sometimes led to temporary collaboration, as illustrated by Feld resident Susan, whose fragmented convoy consisted of her three children who interacted only on holidays and had unilateral care roles. With Susan’s hospitalization for pneumonia, communication increased, as one daughter explained, “We are in a lot of communication when she has a crisis. . . . We are always filling each other in on what the latest is.” Occasionally care was overlooked as happened in Ernest’s fragmented convoy (described earlier in the paragraph) where one person ordered medication and another paid the bills. A staff member noted issues with “the pharmacy holding the medication because they were waiting on payments.”

Discordant convoys

Discordant convoys, 2 of 28, lacked agreement about care goals, including appropriate roles and behaviors. Convoy leadership, particularly among informal caregivers, was either absent, unclear, or contested. Disagreement occurred within informal networks and with assisted living staff or other caregivers. Relative to cohesive and fragmented, predominately discordant convoys typically had the most negative outcomes for residents and caregivers. Hillside’s owner described feuding siblings:

[If the] sibling who is not the POA is not agreeing to the schedule, then the other person can just take them, because they’re not wanting the other one to see them. . . It’s not our place by law to tell the other person to leave if there’s not any order against them being here.

The causes of discord included family dysfunction, off-time caregiving, and an inability or unwillingness to balance care with competing demands. Predominately discordant convoys were the least supportive of residents’ ability to age in place and frequently led to frustration and dissatisfaction among residents and caregivers.

The three convoy types we identified were not mutually exclusive or constant. For instance, two convoys at Garden House experienced marked change in type during the study. Described in the Case Examples section, one predominately cohesive convoy with a primary caregiver experienced a temporary period of discord. And, noted earlier, one fragmented, shared convoy became cohesive during the residents’ health crisis. Another fragmented, shared convoy temporarily transitioned to discordant when a resident’s friend became a romantic interest and assumed an increased care role, a transition unwelcomed by some family members. This discord was problematic for the resident and his convoy members. The fluidity of types reflects the stability and change that defined convoy trajectories.

Case Examples

We provide two examples to illustrate convoy function, adequacy, stability, and change. These cases contain elements of all three types, demonstrate accompanying resident and caregiver outcomes, and highlight key factors that shape how convoys maneuver through care processes over time.

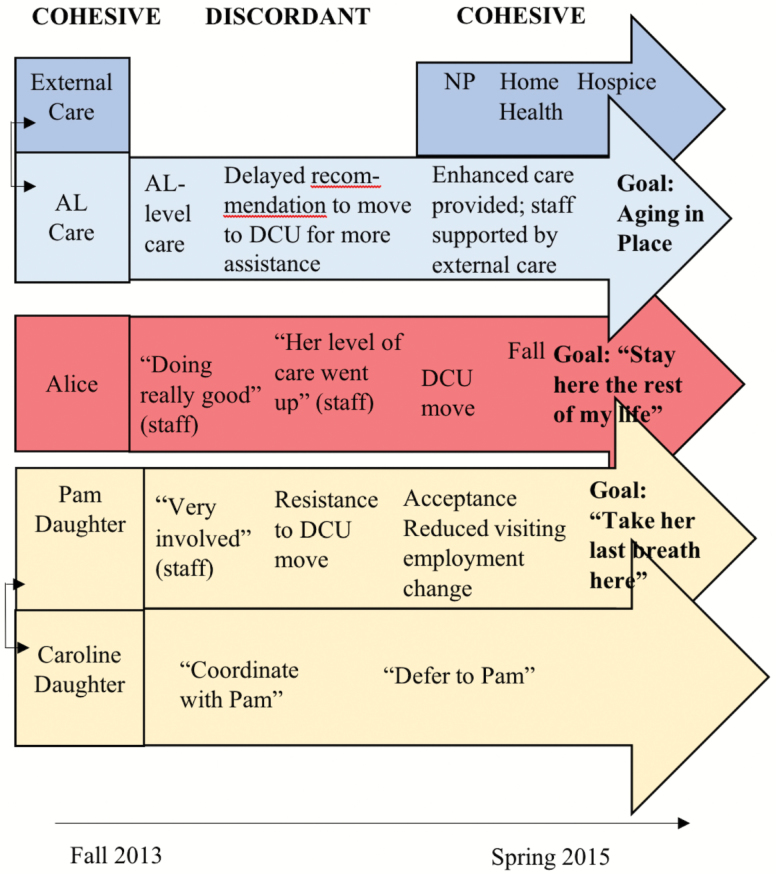

Illustrated in Figure 3, Alice, a Garden House resident, widowed and in her 90s, had a predominately cohesive convoy with a temporary/situational episode of discord and a trajectory with numerous health and convoy changes. Physically frail with cognitive impairment, Alice used a walker, and later a wheelchair, and received staff assistance with all ADLs, some IADLs, medication management, and oversight. The nurse hired by the family to oversee her health care complimented staff saying, “I like the fact that they do get her out of bed and still keep her involved.” Alice’s local daughter, Pam, a health care professional, was the primary informal caregiver. Her participation included health care management, monitoring, visiting, and outings. Pam said: “I don’t have any family or anyone else in the area who comes and visits her. It’s about me. My husband comes sometimes on Sundays with me, and we take her out to eat. . . .” Although she downplayed her husband’s contributions, he visited regularly and often took Alice out. Pam’s out-of-state sister, Caroline, provided money management and visited. Caroline said, “I coordinate with Pam. What I try to do is give her a break.” About decision making she said, “Pam would talk to me about it, but I would absolutely defer to her recommendation both because of her experience with geriatric populations and because she has healthcare power of attorney.” Generally staff described Alice’s support system as “great.” Alice and her daughters were “happy” with care at Garden House. Pam noted, “They’re pretty good to communicate with me when they notice a change.”

Figure 3.

Alice’s convoy trajectory.

Alice’s decline prompted staff to recommend the DCU. The daughters disagreed and “fought” the move for months, creating additional care work and discord. The care coordinator characterized negotiation as “a tough, tough battle,” explaining, “Alice needs toileting because if she’s left to do that alone there’s a lot of clean up involved . . .That was a very hard sell because the staff protected that for so long and wanted to protect her dignity so they didn’t tell her family what was going on.”

Over time, Pam’s employment changes reduced visits and Alice’s “mobility challenges” ended outings. With continued decline, convoy members and the home’s owner collaborated with the goal of honoring Alice’s request to “Stay here the rest of my life.” Alice was placed on hospice and during her last week received around-the-clock care. Hospice kept her “comfortable” and worked with staff and her daughters to help them understand Alice’s progression “along that end-of-life spectrum.” Alice’s cohesive convoy enabled her to age in place with quality care, which enhanced caregiver satisfaction, all positive outcomes.

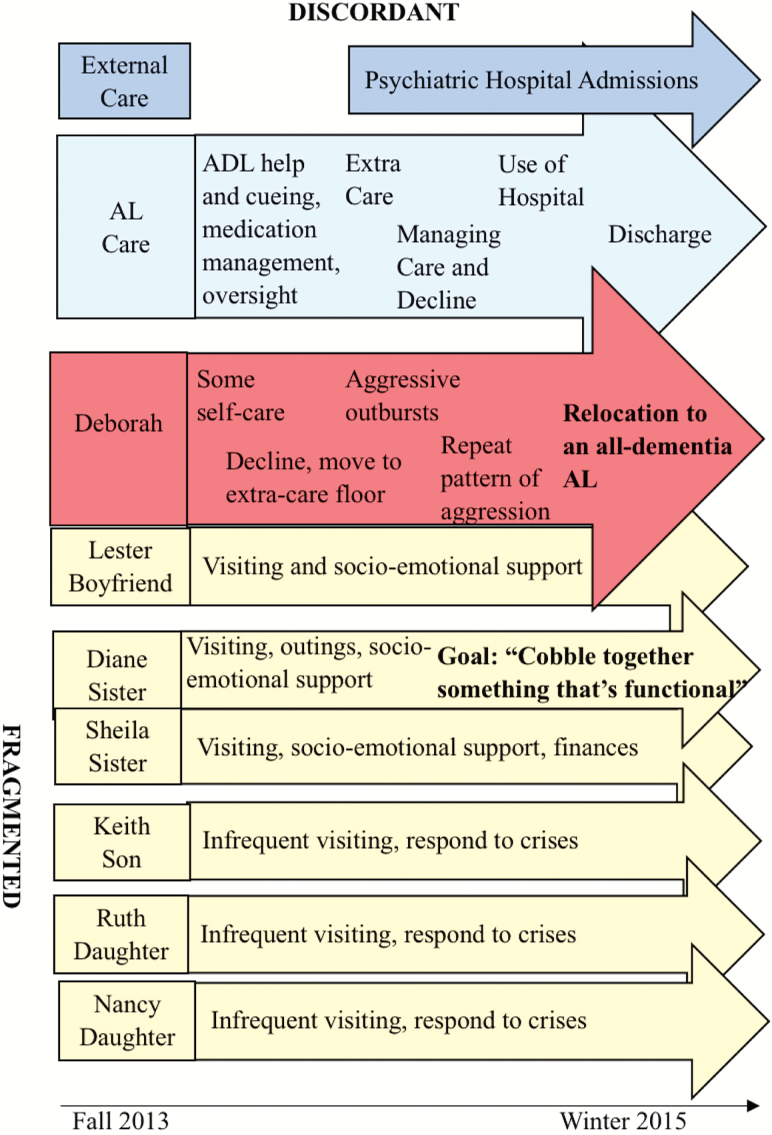

In contrast, Deborah, who moved to Feld House at age 62, 8 years after developing early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, had a convoy with shared informal responsibilities that was fragmented with limited coordination and escalated to discord. Deborah had memory, speech, vision, and mobility deficits and high blood pressure and cholesterol, anxiety, and depression. As Figure 4 illustrates, Deborah performed limited self-care; staff provided help and cueing with all ADLs, medication management, and oversight. Deborah, divorced, had two daughters in their twenties, Ruth and Nancy, and a son, Keith, in his thirties, who were her health care decision makers. Sisters, Diane and Sheila, though, were Deborah’s most involved informal caregivers. According to Sheila, it was “a balancing act” with Diane visiting weekly and handling most IADL tasks. The children visited “maybe once a month if that” and filled in for “urgent things.” Deborah’s boyfriend, Lester, in his 80s, visited when in town for medical appointments and sometimes stayed overnight in Deborah’s room. They talked daily by phone, with help from staff.

Figure 4.

Deborah’s convoy trajectory.

Convoy members’ lives were complicated by jobs and health issues. Their relationships were rocky, then and in past. Sheila termed the family “fractured” and “dysfunctional” stating the kids had “trouble growing up” and lacked knowledge of “how to interact in a loving family.” Communication was emergency-driven, usually by e-mail and text; occasional face-to-face meetings addressed future care in the face of “dwindling” finances. Sheila noted, “Here, you’ve got disparate people with disparate lives and goals and things to do. . . .I feel like Diane and I are like the Jiminy Cricket on Pinocchio’s shoulder, with the kids, ‘This is what she needs’. . . .We’re trying our best to cobble together something that’s functional for Deborah.”

Communication with staff was similarly lacking. Services coordinator, Alexis, described Deborah’s family as “very difficult to get a hold of” and their fragmented roles and unresponsiveness challenging: “If I need something financially, it’s Diane. . .if we need something medically, it’s the kids. So like she just had a couple issues recently and you leave messages and they call back but not necessarily as quickly as we might need. . .and they don’t communicate to us [about] what we can do to make that easier.” Diane welcomed staff support, but noted: “there is still so much to navigate. . . .it would be nice for people to point the way.” Deborah’s decline also was emotionally draining. Keith explained, “On one hand, you want to celebrate that your mother is still there. On the other hand, all you see is how much you have lost. This dichotomy has become a dark cloud hanging over our entire family.”

Deborah’s cognitive decline led to relocation to the extra-care wing. Increasingly aggressive behavior triggered temporary stabilizations in a psychiatric hospital and, finally, discharge. According to Alexis, Deborah “totally destroyed” her room and “physically attacked” three residents. The family remained “very uncooperative, very unhelpful.” That night “. . . nobody answered except for Keith. . .it was like 2 in the morning, and he was like, ‘What do you want me to do?’” To Alexis, families like Deborah’s “can definitely get in the way. . .Keith does not believe that mom is capable of doing the things that we said she was doing. We see her every day; we are not making this up. . . . So it’s communication.” Ultimately, Deborah’s discordant convoy failed to meet her care needs and support aging in place and left convoy members frustrated and burdened.

Discussion

We depart from conventional approaches to studying care by emphasizing intersections of formal and informal care and focusing on entire care convoys studied qualitatively, in-depth, and over time. The process of “maneuvering together, apart, and at odds,” with the accompanying model and convoy typology, illustrate the complexities and dynamics of care experiences, patterns, and influential factors, previously undocumented in the care literature, especially in assisted living and over time. In what follows, we discuss our findings and their implications for care research and practice.

Findings confirm that care recipients are care partners. Residents participated in self-care and care management based on ability, willingness, and extent of convoy support. Existing work documents the importance of self-care for autonomy and independence, which are threatened by safety and convenience in some assisted living settings (Ball et al., 2005; Morgan et al., 2012). Optimizing care recipients’ involvement requires greater caregiver time, patience, and willingness and has implications for well-being and quality of life (Kemp et al., 2013) and must be prioritized in any care setting. Doing so requires communication practices that include care recipients in their own care decisions and activities insofar as possible.

Our work extends Ball et al.’s (2005) distinction between primary and shared informal caregiving by incorporating variation in the structure and dynamic of care convoys and including multiple members. Primary informal caregivers sometimes overlooked the support they had from others. For example, Pam minimized her husband’s contributions, which enhanced Alice’s care and Pam’s respite opportunities. Family members in assisted living report greater burden than those in nursing homes, likely owing to greater involvement (Port et al., 2005; Zimmerman et al., 2013), and are apt to benefit from respite. Reinforcing the need for respite and creating opportunities for meaningful caregiver support through policy and practice can promote resident and caregiver quality of life and care.

Findings shows that shared informal networks have the capacity to distribute responsibility across individuals and enhance access to informal assistance, especially during crises. As in prior research on family caregiving (Pruchno et al., 1997; Pyke & Bengtson, 1996), challenges arose in the absence of clearly defined roles or consensus, both consequential to care outcomes regardless of convoy size and composition. Network size was a complicating factor in our data and noted in Gaugler, Reese, & Sauld (2015) pilot work. Our data also show that although convoy factors were highly influential, resident-, caregiver-, facility-, and community-level factors, could have equal and interactive importance.

Convoys in our study demonstrated the advantages of care planning and goal-setting. Most states require service planning based on periodic assessment of residents’ health and functional status (Carder et al., 2015), but our work shows that goals are not always established or agreed upon within and across care networks, underscoring the need for effective communication. We recommend ongoing discussions that include care recipients and informal and formal convoy members and developing care plans and roles that support established goals.

Case management may be beneficial, particularly when care recipients and informal caregivers are vulnerable or need help navigating the landscape. Some of this responsibility was assumed by assisted living staff, especially care directors. Zimmerman and colleagues (2013) point to the potential value of social workers despite lack of standard regulations governing social services in assisted living. Quantitative assessments indicate interpersonal-conflict between staff and family members in assisted living are rare, but “suggest room for improvement” (Zimmerman et al., 2013, p.549). Fragmentation and discord within convoys, including among and between informal and formal caregivers, were not uncommon even within cohesive convoys, underscoring the potential value of social services in long-term care settings. Our data show the potentially negative outcomes for caregivers and recipients when there is within-convoy disagreement over time.

Inclusion beyond a primary person (Gaugler, 2005) provides a more comprehensive understanding of care than previously existed. As illustrated, parent care frequently is shared among siblings (Connidis & Kemp, 2008), and network changes are common, implying the need to shift caregiving research from “individual” and “cross-sectional approaches to dynamic and systemic analyses” (Szinovacz & Davey, 2013:631). Findings illuminate the contributions of nontraditional informal caregivers who lack normative obligations governing spouses or children. These convoys require further scholarly attention as many individuals now and in future will rely on nontraditional helpers.

Data affirm the consequential nature of informal care for individuals’ quality of life and care and ability to age in place. Formal providers compensated to varying degrees for lack of informal leadership and responsiveness, but this arrangement was not sustainable, especially with limited resident involvement. For example, although Deborah’s shared informal convoy included traditional members, none assumed responsibility and collaboration was absent. Complicating the dysfunctional family context, caregiving occurred “off-time” (Neugarten, Moore, & Lowe, 1965) for her children, who were unable or unwilling to respond. The care context, including care recipients’ needs and caregivers’ capacity to provide care, is highly consequential and renders certain convoys and hence, care recipients, more vulnerable and less supported relative to others. Our work confirms the value of considering informal-formal care intersections (Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003).

Assisted living staff provided most hands-on care and essential emotional support. This low-paid workforce is in need of greater recognition and remuneration (Ball et al., 2010). Escalating resident frailty in assisted living means a growing number of formal care partners and calls into question how best to deliver health care (Kane & Mach, 2007). We provide insight into how care is accomplished, yet this area warrants closer examination as the industry struggles between social and medical care models (Morgan et al., 2012).

Family and friends were consequential to resident care, particularly during decline or crises. As others note, informal caregivers frequently are advocates and important decision-makers. Sharpp and Young (2016:34) found, for instance, that in absence of licensed nurses and training, “strong family involvement was essential” to preventing unnecessary emergency room transfers for assisted living residents with dementia. Engaged informal caregivers and convoy consensus, communication, and collaboration differentiated Alice’s ability to age in place and Deborah’s discharge.

Care convoys were unique, yet all had trajectories shaped by care relationships and contexts and multiple multilevel factors. Due to the complexity of the research design (Kemp et al., 2017), we are able to identify more complex models of care than existing research (e.g., Cantor, 1991; Greene, 1983; Litwak, 1985). All convoys experienced stability and change, but the ability to successfully navigate the latter was not universal. Our case examples also highlight key factors affecting how convoys maneuvered in assisted living and point to those factors that facilitate and constrain quality of life and care. Analysis confirms certain factors identified in the Convoy of Care Model (Kemp et al., 2013). At the regulatory level, Medicare reimbursement for rehabilitation, home health, and hospice services and state assisted living regulations shaped care options and access and affected aging in place. The size and location of a home’s surrounding community influenced options for health care, staffing, and volunteers. Equally influential were assisted living residence factors, including aging in place philosophy and policies, care planning, staffing practices, training, turnover, and resources. Among caregivers, attitudes, beliefs, strategies, knowledge, resources, and availability affected care quality and quantity. Finally, residents’ cognitive and physical function, communication strategies, material and social resources, and relationships affected convoy structure, function, and outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although we believe our research is innovative, it has limitations. First, we formally interviewed multiple informal convoy members and gathered data directly or indirectly for most members, but were unable to formally interview everyone. Certain convoy data are more complete than others. Second, we selected residences that represent the range found in the United States, but the present analysis only uses data from four sites. Future analysis of data from additional sites will build on and extend our present findings. Next, the majority of residents and informal caregivers in our sample had some college or a college degree. Our previous research shows that education, an indicator of social location and access to resources, shapes care options, care relationships, and care experiences (Ball et al., 2009; Perkins et al., 2012). Our ongoing data collection involves participants with rather limited resources and will expand the range of care experiences represented in the present sample. Finally, in order to delve deeply and understand the complexities of convoys, our sample size is limited and we rely on qualitative data and methods. Future research might consider using larger samples, mixed-methods, and interventions targeting communication, consensus, and collaboration to strengthen convoys. Despite limitations, our design shows the value of a comprehensive approach to studying care relationships and illuminates the path to holistic understandings of care and creating collaborative care partnerships in assisted living and other long-term care settings.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01AG044368 to C. L. Kemp).

Conflict of Interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

C. L. Kemp and M. M. Ball took the lead in designing the study and conceptualizing and drafting the manuscript and had lead roles along with M. M. Perkins and J. C. Morgan in data collection and analysis. All authors, including E. O. Burgess and P. J. Doyle, participated in planning the study and analyzing data and contributed to conceptualizing and revising the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who gave so generously of their time and participated in the study. We are very grateful to Joy Dillard and Carole Hollingsworth for their valuable contributions and dedication to the study. Thank you also to Elizabeth Avent, Christina Barmon, Andrea Fitzroy, Victoria Helmly, Russell Spornberger, and Deborah Yoder for assisting with data collection and analysis activities. We are grateful to Tim Merritt for his technical help and to Victor Marshall and Frank Whittington for their feedback and mentorship

References

- Antonucci T. C. (1985). Personal characteristics, social support and social behavior. In R. H. Binstock & E. Shanas (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences, 2nd edition (pp. 94–128). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M., Perkins M. M., Whittington F. J., Hollingsworth C., King S. V., & Combs B. L (2005). Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M., Perkins M. M., Hollingsworth C., & Kemp C. L (Eds.), (2010). Frontline workers in assisted living. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M., Perkins M. M., Hollingsworth C., Whittington F. J., & King S. V (2009). Pathways to assisted living: The influence of race and class. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28, 81–108. doi:10.1177/0733464808323451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black B. S., Rabins P. V., Sugarman J., & Karlawish J. H (2010). Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 77–85. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bd1de2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor M. H. (1991). Family and community: Changing roles in an aging society. The Gerontologist, 31, 337–346. doi:10.1093/geront/31.3.337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder P., O’Keeffe J. & O’Keeffe C (2015). Compendium of residential care and assisted living regulation and policy: 2015 edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2007). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran M. A. (2011). Caregiving styles: A cognitive and behavioral typology associated with dementia family caregiving. The Gerontologist, 51, 463–472. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connidis I. A., & Kemp C. L (2008). Negotiating actual and anticipated parental support: Multiple sibling voices in three-generation families. Journal of Aging Studies, 22, 229–238. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2007.06.002 [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. & Strauss A (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory, 4th Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dill J. S., Morgan J. C., & Kalleberg A. L (2012). Making ‘bad jobs’ better: The case of frontline healthcare workers. In C. Warhurst P. Findlay C. Tilly & F. Carre (Eds.) Are bad jobs inevitable? Trends, determinants and responses to job quality in the twenty-first century (pp. 110–127). UK: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. H. (1998). The life course and human development. In R. M., Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 939–991). New York: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E. (2005). Family involvement in residential long-term care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging & Mental Health, 9, 105–118. doi:10.1080/13607860412331310245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., & Kane R. L (2007). Families and assisted living. The Gerontologist, 47, 83–99. doi:10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., Reese M., & Sauld J (2015). A pilot evaluation of psychosocial support for family caregivers of relatives with dementia in long-term care: The residential care transition module. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 8, 161–172. doi:10.3928/19404921-20150304-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene V. L. (1983). Substitution between formally and informally provided care for the impaired elderly in the community. Medical Care, 21, 609–619. doi:10.1097/00005650-198306000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L., Sengupta M., Park-Lee E. et al. (2016). Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National study of Long-Term Care providers, 2013–2014. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. L. & Antonucci T. C (1980). Convoys over the life course: A life course approach. In P. B. Baltes & O. Brim (Eds.), Life span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. L., & Mach J. R (2007). Improving health care for assisted living residents. Gerontologist, 47, 100–109. doi:10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., & Perkins M. M (2013). Convoys of care: Theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 15–29. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., Morgan J. C., Doyle P. J., Burgess E. O, Dillard J., Barmon C. B., Fitzroy A. F., Helmly V. E., & Avent E., & Perkins M. M (2017). Exposing the backstage: Critical reflections on a longitudinal qualitative study of residents’ care networks in assisted living. Qualitative Health Research, 25, 1190–1202. doi:10.1177/1049732316668817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., & Perkins M. M (forthcoming). “Charting the course: An account of the analytic processes used in the Convoy Study.” In Áine Humble and Elise Radiname (Eds.) Going beyond ‘themes emerged’: Real stories of how qualitative analysis happens. Oxon, UK: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E. (1985). Helping the elderly: The complementary roles of informal networks and formal systems. New York: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews S. H. (2002). Sisters and brothers/daughters and sons: Meeting the needs of old parents. Bloomington, IN: Unlimited Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L. A., Frankowski C. A., Roth E. G., Keimig L., Zimmerman S., & Eckert J. K (2012). Quality assisted living: Informing practice through research. New York: Spring. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. NAC and AARP Public Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2009). Research involving individuals with questionable capacity to consent: Points to Consider http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/questionablecapacity.htm

- Neugarten B. L., Moore J. W., & Lowe J. C (1965). Age norms, age constraints, and adult socialization. American Journal of Sociology, 70, 710–717. doi:10.1086/223965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (2015). Qualitative methods and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M. M., Ball M. M., Kemp C. L., & Hollingsworth C (2013). Social relations and resident health in assisted living: An application of the convoy model. The Gerontologist, 53, 495–507. doi:10.1093/geront/gns124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port C. L., Zimmerman S., Williams C. S., Dobbs D., Preisser J. S., & Williams S. W (2005). Families filling the gap: Comparing family involvement for assisted living and nursing home residents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 45, 87–95. doi:10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R. A., Burant C. J., & Peters N. D (1997). Typologies of caregiving families: Family congruence and individual well-being. The Gerontologist, 37, 157–167. doi:10.1093/geront/37.2.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyke K. D. & Bengtson V. L (1996). Caring more or less: Individualistic and collectivistic systems of family eldercare. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58, 370–392. doi:10.2307/353503 [Google Scholar]

- Sharpp T. J., & Young H. M (2016). Experiences of frequent visits to the emergency department by residents with dementia in assisted living. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 37, 30–35. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz M. E. & Davey A (2013). Changes in adult children’s participation in parent care. Ageing & Society, 33: 667–697. doi:10.1017/S0144686X12000177 [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Griffin C. & Marshall V. W (2003). Reconceptualizing the relationship between “public” and “private” eldercare. Journal of Aging Studies, 17, 189–208. doi:10.1016/S0890-4065(03)00004-5 [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Cohen L. W., Reed D., Gwyther L. P., Washington T., Cagle J. G., Beeber A. S., & Sloane P. D (2013). Comparing families and staff in nursing homes and assisted living: Implications for social work practice. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 56, 535–553. doi:10.1080/01634372.2013.811145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]