Abstract

Objective

Although numerous studies suggest a salutary effect of exercise on mood, few studies have explored the effect of exercise in patients with complex mental illness. Accordingly, we evaluated the impact of running on stress, anxiety and depression in youth and adults with complex mood disorders including comorbid diagnoses, cognitive and social impairment and high relapse rates.

Methods

Participants were members of a running group at St Joseph Healthcare Hamilton’s Mood Disorders Program, designed for clients with complex mood disorders. On a weekly basis, participants completed Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) questionnaires, providing an opportunity to evaluate the effect of running in this population.

Results

Data collected for 46 participants from April 2012 to July 2015 indicated a significant decrease in depression (p<0.0001), anxiety (p<0.0001) and stress (p=0.01) scores. Whereas younger participant age, younger age at onset of illness and higher perceived levels of friendship with other running group members (ps≤0.04) were associated with lower end-of-study depression, anxiety and stress scores, higher attendance was associated with decreasing BDI and BAI (ps≤0.01) scores over time.

Conclusions

Aerobic exercise in a supportive group setting may improve mood symptoms in youth and adults with complex mood disorders, and perceived social support may be an important factor in programme’s success. Further research is required to identify specifically the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic benefits associated with exercise-based therapy programmes.

Keywords: exercise, anxiety, stress, tertiary care, mood disorders, major depressive disorder, depressive disorder, treatment-resistant

What are the new findings?

A group-based running programme provided therapeutic benefit to youth and adults with complex mood disorders, characterised by comorbid diagnoses, ongoing cognitive and social impairment and high relapse rates.

The therapeutic benefits of a structured group exercise programme may be impacted by higher attendance, social support and younger participant age.

Clinical features of mental illness, such as age at onset of illness, may also impact programme outcomes.

Background

Mood disorders are a prevalent and costly social and health issue affecting 350 million people worldwide.1 In keeping with established guidelines, antidepressants, mood stabilisers and psychotherapy are considered first-line agents in the treatment of depression and bipolar disorder (BD).2 3 The response rate to first-line treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD), however, is only about 50%–65% and is associated with significant relapse.4 Moreover, although approximately 33% of persons are expected to recover fully following first-line treatment,5 remission is often characterised by residual symptoms including depressed mood, decreased concentration and hopelessness in MDD6 and in BD7 and higher rates of mortality across all-cause mortality.8 9 Medication adherence in patients with mood disorders remains low, ranging from 30% to 70% for antidepressants and from 18% to 52% for mood stabilisers.10 11 Antidepressant treatment costs represent an additional mental health burden in Canada, having ballooned from $31.4 million in 198112 to an estimated $1.2 billion in 2005.13 These figures suggest that more effective treatment options are needed urgently for the management of mood disorders.

Aerobic exercise as a possible therapeutic intervention for complex mood disorders is supported by several lines of evidence. In animal models, as depressive symptoms increase, physical function decreases; conversely, decreased physical function is associated with increased depressive-like behaviour.14 In humans, some studies have reported a positive improvement in depressive symptoms after the adoption of exercise across youth15 and adults16–19 with MDD; other studies have reported no significant effects in MDD symptoms compared with non-exercising20 or placebo (stretching)21 groups. A recent meta-analysis of 15 randomised trials evaluating the effect of exercise on MDD found a significant effect of exercise across a variety of measures of depression, with a mean effect size of 0.77 for all studies and of 0.43 for studies that met higher methodological criteria.22 Methodological variability may partly underlie the discrepancy of results, including exercise duration and type (aerobic vs non-aerobic) and level of social interaction (e.g., minimal,21 23 supervised16 19 21 23 or group-based).15 24 25 Critically, there also remains little information about the potential therapeutic benefits of exercise on complex mood disorders, including those that are treatment resistant, as most randomised controlled trials exclude individuals with previous poor treatment response.16 23 26 Moreover, studies that have included participants with treatment-resistant mood disorders did not evaluate the impact of clinical history (e.g., illness duration and comorbid diagnoses) on treatment response.18 27

To address the above gaps in the literature, we investigated the impact of exercise in youth and adults with complex clinical histories and treatment-resistant mood disorders, as these patients are rarely included in clinical trials. Since April 2012, a multidisciplinary clinical team in the Mood Disorders Program, St Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton (Hamilton, Ontario) has offered a 12-week group-based recreational running programme aimed at enhancing clinical outcomes in youth and adults with mood and anxiety disorders. As part of the programme evaluation, the team collected weekly self-report measures of stress, anxiety and depression and perceived social support, which provided an opportunity to evaluate the impact of running in youth and adults in a sample that included complex mood disorders. The primary goal of the current study was to assess the impact of a structured aerobic exercise programme on measures of stress, anxiety and depression over 12 weeks in youth and adults with complex mood disorder histories. The secondary objectives were to explore the impact of demographic and clinical factors including: (1) participant age; (2) attendance; (3) clinical history; and (4) perceived social support on outcome measures of stress, anxiety and depression.

Methods

The current study is a retrospective chart review analysing data that were collected as part of the ongoing evaluation of the Team Unbreakable running group programme. Data were available for participants from August 2012 to July 2015, which spanned 11 running group sessions (see table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the running groups

| Group | Starting date | Age | Female, n (%) | Number of runners |

| 1 | April 2012 | Youth | 5 (62.5) | 8 |

| 2 | August 2012 | Youth | 5 (71.4) | 7 |

| 3 | April 2013 | Youth | 3 (75.0) | 4 |

| 4 | August 2013 | Adult | 5 (83.3) | 6 |

| 5 | September 2013 | Youth | 2 (100) | 2 |

| 6 | April 2014 | Adult | 3 (100) | 3 |

| 7 | April 2014 | Youth | 0 (0) | 3 |

| 8 | August 2014 | Adult | 3 (75.0) | 4 |

| 9 | September 2014 | Youth | 4 (100) | 4 |

| 10 | March 2015 | Adult | 4 (100) | 4 |

| 11 | March 2015 | Youth | 1 (100) | 1 |

| Total | 35 (76.1) | 46 |

Participants

Participants were 46 running group members at St Joseph Healthcare Hamilton’s Mood Disorders Program, organised as part of a novel treatment programme for clients with mood disorders in the Hamilton community. Participants were allocated to a youth (n=29; 16–25 years) or adult (n=17; >25 years) group based on their age. Recruitment methods included flyers in and around the hospital and distributing information to local clinics. Referral criteria included: history of BD, MDD or anxiety disorder, including those not in full remission and/or with comorbid diagnoses, and the ability to participate in a 12-week running programme, confirmed by the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q & You).28 The primary clinical diagnosis of mood disorder was confirmed from review of the patient medical record. A total of 10 participants were excluded from the analyses due to missing diagnostic information in the medical chart (n=8) and the absence of a primary diagnosis of a mood disorder (n=2; one had general anxiety disorder and one had schizoaffective disorder).

Clinical assessments

Beck Depression Inventory second edition (BDI-II; PsychCorp)29: a 21-item self-report questionnaire used to assess depressive symptoms.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; PsychCorp)30: a 21-item self-report questionnaire used to assess symptoms of anxiety.

Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)31: a 10-item self-report questionnaire measuring the degree to which situations are perceived as stressful.

36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36)32 33: a 36-item self-report assessment that measures health-related quality of life. The survey generates a score that can be subdivided into eight subscales: limitations in physical activities, limitations in social activities due to physical health, limitations in usual activities due to physical health, bodily pain, general mental health, limitations in usual activities due to emotional problems, vitality and general health perceptions.

Running log assessments

Before and after every run, participants rated their mood, energy level, enthusiasm, stress and feelings of friendship with other group members on a scale of 0–10. This survey included a question asking participants to rate their level of connection with the group, which provided an estimate of perceived social support.

Running protocol

Participants met twice per week and progressed from mostly walking to mostly running. In the 13th week, participants completed a local 5 km run as a group. Weekly sessions included motivational talks across a range of topics such as mental illness, running strategies, nutrition and mindfulness. The sessions also provided an opportunity for participants to interact with each other, the clinical leads (recreation therapist (JW) and social worker (KM)), and volunteers comprised of hospital staff, faculty and graduate students. The programme was flexible to meet the needs of the participants but started out as a 1-km session of 30 s running and 2 min walking. Each week, the participants went a little farther and increased the time spent running by 30–60 s. The goal was to work up to mostly running for 5 km by week 12.

Statistical analyses

The primary objective was evaluated using: (1) a mixed-model repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate BDI, BAI and PSS score changes over time and (2) assessment of remission and response of BDI scores. Due to variable attendance of participants, there were large amounts of missing data at random time points, resulting in varying sample sizes across analyses. A mixed-model approach was chosen as it is more effective at handling missing data than the general linear model,34 provided the time points of the missing data are random,35 and does not assume that repeated observations over time are independent.34 Remission and response were defined as follows: total BDI <12 to define remission of depressive symptoms and a decrease of 50% from baseline to end of study in BDI score to define response. 36 The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 was used to assess movement across the BDI ranges (absent, low, moderate and high) from baseline to end of study.37

Secondary objectives were assessed using autoregression analyses to identify predictors of BDI, BAI and PSS score changes over time. Factors assessed included age, gender, attendance, age of illness diagnosis (the age the participant first received counselling or medication), comorbid diagnoses and perceived social support. Clinical history was obtained through medical record review. We explored the impact of perceived social support using the responses to the question ‘Level of friendship with other group members’, which the participants scored on a scale of 1–10 in the Running Log tool. The Running Log social support question was validated by comparing results with the social subscale of the SF-36, which was available for a subset of participants. Finally, we evaluated single item responses of the BDI and the BAI using the mixed-models method to investigate the effect of the running therapy programme on single items of possible clinical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 for Windows.

Results

There were fewer male (11; 23.9%) than female (35; 76.1%) participants; χ2=12.5, df=1, p=0.0004. The average (±SD) age of the adult group was 45.2 (±12.9) years, and the average age of the youth group was 22.1 (±5.8) years. All patients had a primary diagnosis of a mood disorder. Clinical and demographic data were available for 46 participants and are summarised in table 1. The primary diagnoses for the current sample were major depressive disorder (n=29), BD (n=13), major depressive disorder and dysthymia (n=3) and dysthymia (n=1). In addition, 10 participants had current suicidal ideation, 6 had a history of psychotic symptoms and 25 of the participants had one or more comorbid psychiatric diagnoses.

Mixed-model repeated measures analysis: depression, anxiety and stress scales over time

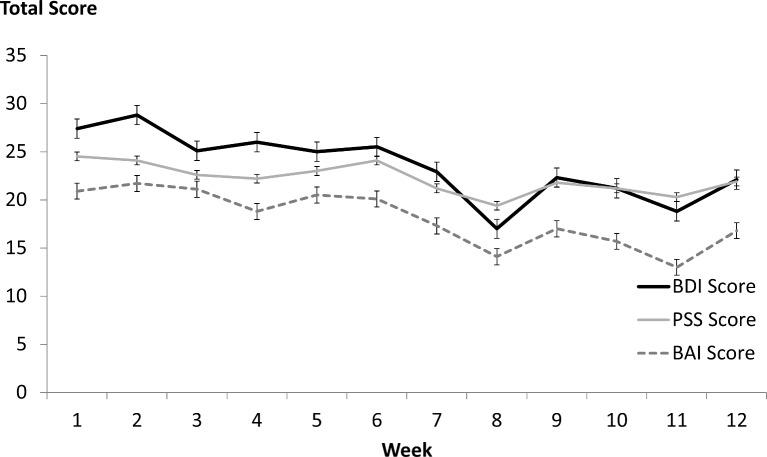

A mixed-model repeated measures ANOVA of BDI scores revealed a significant decrease in depressive symptoms from baseline to end of study (F=4.5, df=11, 201, p<0001), observable for the youth (F=2.1, df 11, 118, p=0.02) and adult groups (F=4.3, df 11, 72; p<0.0001). Results were similar for BAI (F=4.8, df=11, 186, p<0.0001) and PSS (F=2.3, df=11, 186, p=0.01) scores; results held when adults and youth were analysed separately (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stress, anxiety and depression scores over time. Figure 1 illustrates the changes in self-report scores of the BDI (solid black line), PSS (solid grey line) and BAI (dashed black line) scores in participants over time. BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

Remission: BDI scores were categorised by levels of depression as absent (<12); low (13–19); moderate (20–28) and high (>29).29 BAI scores were classified as absent (≤9), low (10–18), moderate (19–29) and high (≥30).38 From baseline to end of running session, there was a decline in the number of participants with moderate or severe BDI scores, with corresponding increases of participants in the low and absent categories. A similar pattern of results was identified for BAI scores (see table 2).

Table 2.

Remission rates of baseline compared with end-of-study depression and anxiety scores

| Baseline (n=35) (n (%)) | End of study (n=20) (n (%)) | Change (%) | Comparison | |

| BDI scores | ||||

| High | 16 (45.7) | 4 (20.0) | −43.8 | χ2= 6.9, df=3, p=0.08 |

| Moderate | 10 (28.6) | 4 (20.0) | −30.0 | |

| Low | 5 (14.3) | 6 (30.0) | +52.3 | |

| Absent | 4 (11.4) | 6 (30.0) | +62.0 | |

| BAI scores | ||||

| High | 10 (32.2) | 1 (4.4) | −86.3 | χ2= 4.6, df=3, p=0.03 |

| Moderate | 8 (25.8) | 5 (21.7) | −15.9 | |

| Low | 5 (16.1) | 6 (26.1) | +38.3 | |

| Absent | 8 (25.8) | 11 (47.8) | +46.0 | |

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Response to treatment

In adults, baseline compared with end of study BDI scores were 30.8 (±14.5; range 10–58; sample size n=12) versus 18.8 (±12.6; range 11–41; sample size n=5), an overall decrease of approximately 39%. In youth, baseline compared with end-of-study BDI scores were 26.9 (±13.0; range 2–48; sample size n=23) versus 19.5 (±15.5; range 0–59; sample size n=15), an approximately 27% decrease. Nineteen participants had both baseline and end-of-study data available; of these, five participants (26.3%) showed a decrease of 50% or more in their post-BDI score.

Secondary objectives

Autoregression analyses were used to explore the impact of participant age, age at diagnosis, number of comorbid diagnoses and perceived social support (level of friendship with the group) on stress, anxiety and depression. Perceived social support was estimated by the postrunning ‘Level of friendship’ item in the Running Log. In order to validate this variable, we assessed the correlation between the end-of-study postrunning level of friendship score and relevant subscales of the SF-36 questionnaire available for a subset of participants (n=18) and identified correlations between level of friendship and SF-36 mental health subscales of social func tioning (r=0.41, p=0.001), role of emotions in functioning (r=0.37, p=0.003), vitality (r=0.45, p=0.0002) and mental health (r=0.46, p=0.0002). Perceived level of friendship with the group after running was predictive of BDI (t=−4.0 p<0.0001), PSS (t=−2.1, p=0.04) and BAI scores (t=−3.6, p=0.0003), where higher levels of perceived friendship were associated with lower scores on all measures from week 1 to week 12. Attendance was also a significant predictor of mood scores, where higher attendance predicted lower BDI (t=−2.5 p=0.01) and BAI (−3.4, p=0.007) scores, with a trend for lower stress scores (t=−1.7, p=0.084). Age at onset of illness significantly predicted BDI (t=9.4, p<0.0001), BAI (t=6.2, p<0.0001) and PSS (t=6.3, p<0.0001) scores; an earlier age of illness onset was associated with decreased depression, anxiety and stress scores from baseline to end of study. Age was a significant predictor of BDI (t=5.9, p<0.0001), BAI (t=3.3, p=0.001) and PSS (t=6.6, p<0.0001) scores; younger age was associated with lower mood scores over time.

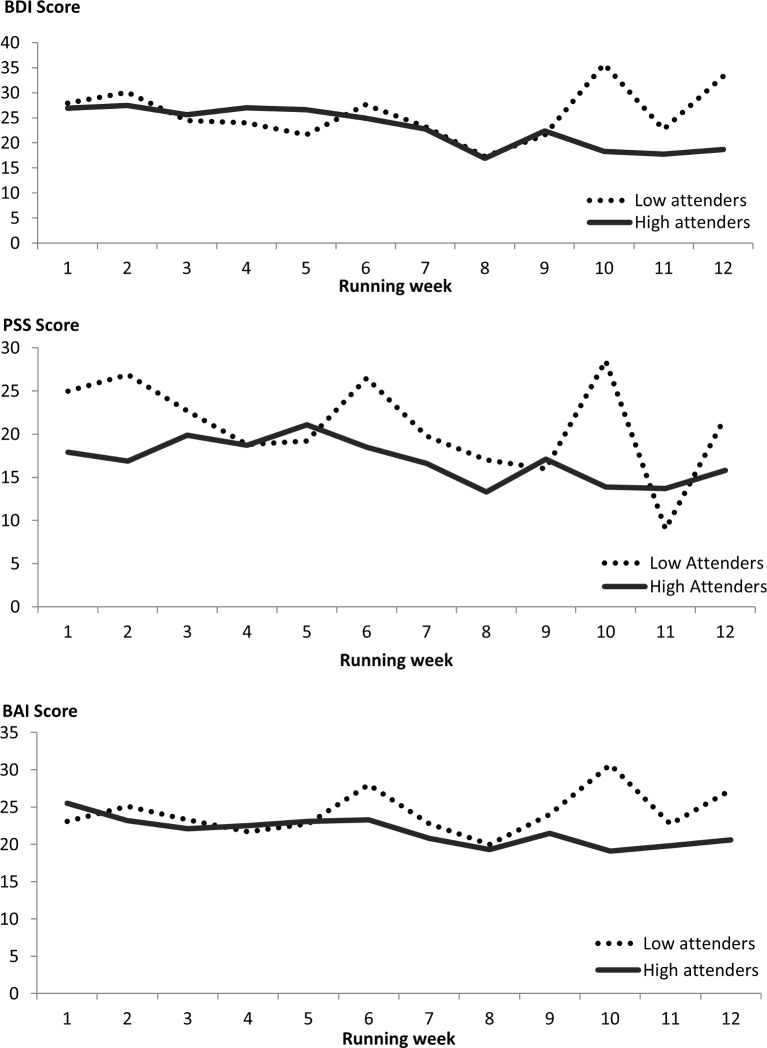

Programme compliance

The attendance rate was 49.2% (±27.5); not significantly higher for adults (55.0% (±24.6)) compared with youth (44.8% (±28.6); t=1,2, df=44; p=0.2). We split the group into high (attended more than 50% of running sessions, n=23) and low (attended 50% or less running sessions, n=23) attenders and observed a non-significant difference in end-of-programme BDI scores, with those that attended more frequently having lower scores (16.2±14.7) compared with those that attended less frequently (28.8±9.7; t=−1.8, df=23, p=0.092). However, as illustrated in figure 2, this result may be influenced by high variability of the low attendance group.

Figure 2.

Changes in scores for the BDI (top graph), PSS (middle graph) and BAI (bottom graph) for high and low attenders. Top graph: BDI scores for participants who attended 50% or fewer (dotted black line) compared with more than 50% (solid grey line) sessions over the 12 weeks of the running therapy sessions. Middle graph: PSS scores for participants who attended 50% or fewer (dotted black line) compared with more than 50% (solid grey line) sessions over the 12 weeks of the running therapy sessions. Bottom graph: BAI scores for participants who attended 50% or fewer (dotted black line) compared with more than 50% (solid grey line) sessions over the 12 weeks of the running therapy sessions. BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

Additional analyses for this study can be reviewed in the online supplementary data.

bmjsem-2017-000314supp001.docx (19.2KB, docx)

Discussion

The results from the present study suggest that adults and youth with complex mood disorders can benefit from a running therapy programme that is supervised by clinical professionals in a group setting that offers social support. Interventions such as exercise are being promoted as having therapeutic benefits to youth and adults with mood disorders.22 However, most research in this area is based on first-episode patients and/or excludes participants with treatment-resistant depression and BD.39 Critically, this work also rarely evaluates the impact of exercise in terms of clinical outcomes, nor is there research on exercise type, intensity, the role of social support and/or the impact of exercise on functional outcomes.40 In the current study, we found engagement in a group running programme improved mood symptoms including depression, anxiety and stress in participants with complex mood disorders, over a period of 12 weeks. This finding held for both adult and youth participants with MDD and BD, indicating the running group programme had a positive impact on self-reported symptoms of depression over time. Multiple subitems within the depression inventory also improved over time, including energy, irritability, self-worth and pessimism (refer to online supplementary data). These findings are consistent with previous reports of increased energy and self-esteem levels in adults,22 even after as little as one running session.41 Improved mood scores were predicted by younger age, earlier age at onset of mood disorder, as well as higher attendance to the running programme. We also observed a positive impact of the running therapy programme on perceived social support, as reflected by the relationship between increased feelings of friendship and decreased mood scores, suggesting that the opportunity to connect with peers through the running group may positively impact mood outcomes. Given that social dysfunction is a core symptom of mood disorders, the perceived social support in a structured running programme may help improve psychosocial outcomes in this population.42

There is abundant research on the positive impact of aerobic15 16 18 21 25 and non-aerobic (stretching and yoga)16 27 43 exercise on symptoms of depression, and results have been shown across varying methodologies, samples, exercise programme and assessment strategies. However, most studies exclude complex and/or treatment-resistant populations and do not investigate the impact of other contributing factors such as programme adherence or perceived social support in group or supervised settings. Accordingly, there are knowledge gaps on exercise as a potential therapeutic option for individuals with mood disorders, especially complex forms with comorbid diagnoses and poor response to treatment.

Although the results reported here are encouraging, they should be considered a starting point for further investigation. The large amounts of missing data were a limiting factor for data analyses and interpretation of results. The social support finding, although interesting, was based on an informal tool. Therefore, further research is warranted, using validated questionnaires, to explore the role of perceived social support in structured exercise programme. It is noteworthy that, despite methodological limitations, we identified several positive findings that could result in short-term and long-term clinical and functional benefits to patients with complex mood disorders. As such, the findings reported here should be a starting point for future randomised control trials designed to better understand the potential therapeutic benefits of exercise across the spectrum of mood disorder diagnoses symptoms.

In spite of limited data on clinically relevant variables such as age at onset of illness and comorbid diagnoses, these results also suggest that clinical history may influence outcomes of running for youth and adults with complex mood disorders. Somewhat counterintuitively, we found that both earlier age at onset of illness as well as younger age were associated with lower BDI scores over time. It is possible that the adult group represents a more treatment-resistant form of mood disorder in the current study; future research is recommended to further explore this finding.

Conclusions

In a sample of youth and adults with complex mood disorders, we demonstrated a positive impact of aerobic exercise on symptoms of depression in a supportive group setting over a 3-month period. The results indicate a need for future research of the long-term effects of aerobic exercise in youth and adults with chronic, recurrent and/or treatment-resistant mood disorders to better understand possible therapeutic effects of a structured exercise programme. Moreover, the impact of clinical factors such as age at onset of mood disorder, duration of illness and comorbid diagnoses as well as perceived social support should be explored to determine how these factors impact outcomes. Future randomised trials are warranted to identify when exercise may be useful as a therapeutic option for patients with chronic and/or treatment-resistant mood disorders, and what clinical and improvements can reasonably be expected in this population.

Acknowledgments

We would like thank running coach volunteers Jenna Boyd, Lauren Cudney, Beth Kennedy, Kathryn Litke, Anthony Nazarov, Melissa Parlar and Ryan Pyrke. Esther Pauls from the Running Den is also thanked for her assistance with group leadership. We would also like to acknowledge Danielle Berman from the Ride Away Stigma campaign’s fundraising effort.

Footnotes

Contributors: LEK was the primary author and performed the majority of the assessments and all of the data analyses. SB was involved in the design of the study, in particular surrounding cognitive assessments, and provided direction to the analyses, interpretation of findings, and writing of the paper. KM, JW and LG assisted with design of the running programme, recruitment of participants and weekly data collection; BNF was involved with the design of the study, providing advice for data analyses and interpretation and for writing of the manuscript; RS was coprincipal Investigator on this study. He was involved in the design of the study and provided guidance surrounding data analyses and interpretation and writing of the manuscript. MM was coprincipal investigator on this study. She was involved in the design of the study provided directions surrounding clinical assessments, interpretation of the findings and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: St Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton Foundation provided funding to support this study; specifically, we wish to acknowledge the following donors: Ontario Endowment for Children & Youth Recreation Fund at the Hamilton Community Foundation; Canadian Tire Financial Services; FGL Sports Ltd; Telus; and Jackman Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (HIREB), reference number 14-671-C. Informed consent was not obtained from the participants of this study as the data were collected as a retrospective chart review.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors do not have additional, unpublished data from the study to share with other researchers.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. CANMAT Depression Work Group. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2016;61:540–60. 10.1177/0706743716659417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord 2013;15:1–44. 10.1111/bdi.12025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller MB, et al. Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:809–16. 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100053010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:28–40. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacoviello BM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, et al. The early course of depression: a longitudinal investigation of prodromal symptoms and their relation to the symptomatic course of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol 2010;119:459–67. 10.1037/a0020114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaya E, Aydemir O, Selcuki D. Residual symptoms in bipolar disorder: the effect of the last episode after remission. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2007;31:1387–92. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, et al. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34-38 years. J Affect Disord 2002;68(2-3):167–81. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00377-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kupfer DJ. The increasing medical burden in bipolar disorder. JAMA 2005;293:2528–30. 10.1001/jama.293.20.2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott J, Pope M. Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:1927–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemels ME, Koren G, Einarson TR. Increased use of antidepressants in Canada: 1981-2000. Ann Pharmacother 2002;36:1375–9. 10.1345/aph.1A331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mood Disorders Society of Canada. Quick Facts: Mental Illness & Addiction in Canada. Guelph, ON, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenwood BN, Fleshner M. Exercise, learned helplessness, and the stress-resistant brain. Neuromolecular Med 2008;10:81–98. 10.1007/s12017-008-8029-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nabkasorn C, Miyai N, Sootmongkol A, et al. Effects of physical exercise on depression, neuroendocrine stress hormones and physiological fitness in adolescent females with depressive symptoms. Eur J Public Health 2006;16:179–84. 10.1093/eurpub/cki159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2349–56. 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med 2000;62:633–8. 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knubben K, Reischies FM, Adli M, et al. A randomised, controlled study on the effects of a short-term endurance training programme in patients with major depression. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:29–33. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.030130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trivedi MH, Greer TL, Church TS, et al. Exercise as an augmentation treatment for nonremitted major depressive disorder: a randomized, parallel dose comparison. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:677–84. 10.4088/JCP.10m06743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonhauser M, Fernandez G, Püschel K, et al. Improving physical fitness and emotional well-being in adolescents of low socioeconomic status in Chile: results of a school-based controlled trial. Health Promot Int 2005;20:113–22. 10.1093/heapro/dah603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Doraiswamy PM, et al. Exercise and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychosom Med 2007;69:587–96. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318148c19a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Archer T. Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014;24:259–72. 10.1111/sms.12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh J, Videbech P, Thomsen C, et al. DEMO-II trial. Aerobic exercise versus stretching exercise in patients with major depression-a randomised clinical trial. PLoS One 2012;7:e48316 10.1371/journal.pone.0048316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veale D, Le Fevre K, Pantelis C, et al. Aerobic exercise in the adjunctive treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial. J R Soc Med 1992;85:541–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annesi JJ. Changes in depressed mood associated with 10 weeks of moderate cardiovascular exercise in formerly sedentary adults. Psychol Rep 2005;96(3 Pt 1):855–62. 10.2466/pr0.96.3.855-862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daley AJ, Copeland RJ, Wright NP, et al. Exercise therapy as a treatment for psychopathologic conditions in obese and morbidly obese adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2006;118:2126–34. 10.1542/peds.2006-1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mather AS, Rodriguez C, Guthrie MF, et al. Effects of exercise on depressive symptoms in older adults with poorly responsive depressive disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:411–5. 10.1192/bjp.180.5.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. PAR-Q & You: A Questionnaire for People Aged 15 to 69, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd edn San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:893–7. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.JE WJ, Kosinski M, Keller M. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Users' Manual. edn. Boston: The Health Institute, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolfinger R, Chang M. Comparing the SAS® GLM and MIXED Procedures for Repeated Measures. Cary, NC: SAS® Institute Inc, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Littel RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, et al. SAS for Mixed Models. edn. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riedel M, Möller HJ, Obermeier M, et al. Response and remission criteria in major depression--a validation of current practice. J Psychiatr Res 2010;44:1063–8. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald JH. Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for repeated tests of independence In: Handbook of Biological Statistics. 3rd edn Baltimore, Maryland: Sparky House Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. edn. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malhi GS, Byrow Y. Exercising control over bipolar disorder. Evid Based Ment Health 2016;19:103–5. 10.1136/eb-2016-102430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greer TL, Kurian BT, Trivedi MH. Defining and measuring functional recovery from depression. CNS Drugs 2010;24:267–84. 10.2165/11530230-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pretty J, Peacock J, Sellens M, et al. The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. Int J Environ Health Res 2005;15:319–37. 10.1080/09603120500155963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greer TL, Trombello JM, Rethorst CD, et al. Improvements in psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life following exercise augmentation in patients with treatment response but nonremitted major depressive disorder: Results from the TREAD study. Depress Anxiety 2016;33:870–81. 10.1002/da.22521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buffart LM, van Uffelen JG, Riphagen II, et al. Physical and psychosocial benefits of yoga in cancer patients and survivors, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer 2012;12:559 10.1186/1471-2407-12-559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2017-000314supp001.docx (19.2KB, docx)